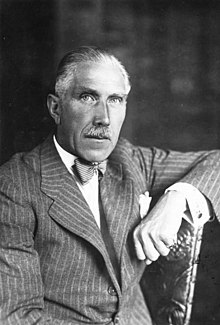

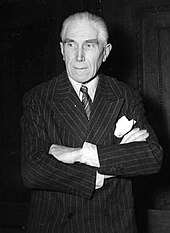

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl and Neuwerk (born October 29, 1879 in Werl ; † May 2, 1969 in Obersasbach ) was a German politician (1921 to 1932 center , then non-party , 1938 NSDAP ) and diplomat who at the end of the Weimar Republic made a decisive contribution to bringing Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP to power.

The former professional officer and member of the Prussian state parliament was appointed Chancellor by Reich President Paul von Hindenburg in June 1932 . In its half-year tenure, he deposed the so-called blow to Prussia the SPD -led government of the Free State of Prussia and thus weaken both federalism and the democracy in Germany. After his fall in December 1932, he negotiated with Hitler about a coalition government between the national-conservative DNVPand the NSDAP. This government, in which von Papen believed he could control the National Socialists, came about on January 30, 1933 ( seizure of power ). He himself took over the office of Vice Chancellor in the Hitler cabinet , but was quickly ousted and resigned after the so-called Röhm Putsch in July 1934. Then he was envoy and ambassador of the German Empire in Vienna and Ankara .

After the Second World War , he was indicted in the Nuremberg Trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Tribunal and acquitted on all counts. As part of the denazification process , he was finally classified as the “main culprit” in a court case on February 24, 1947 and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp. According to a ruling by the Nuremberg Appeals Chamber on January 26, 1949, he was released early that year.

Live and act

Life in the Empire (1879-1919)

Franz von Papen came from the von Papen-Koeningen family, the older line of the Westphalian noble family von Papen , who had acquired wealth and nobility titles in Werl as a heiress , that is, through salt extraction . He was born as the third of five children of the Catholic officer and landowner Friedrich von Papen -Köningen. When he was eleven, his parents sent him to a cadet school at his own request . The training there laid the foundation for his further military career. It led him through the Royal Page Corps at the Emperor's court and the Westphalian Uhlan Regiment No. 5 in Düsseldorf to the General Staff , to which he was a captain from 1913 . There he made numerous acquaintances that were decisive for his later career, including Kurt von Schleicher . In addition, von Papen was considered an enthusiastic and successful equestrian .

In 1905 von Papen married Martha von Boch-Galhau (1880–1961), one of the heiresses of the well-known ceramic dynasty Villeroy & Boch . In addition to considerable financial resources, she also brought an estate in Wallerfangen (Saar) into the marriage, which had been known as Gut Papen since 1905 and which is still owned by the family today. In addition, through his wife, von Papen gained crucial contacts to industrial circles in the Rhineland for his later career. The marriage produced a son, Friedrich Franz von Papen (1911–1983), and four daughters: Antoinette (1906–1993), Margaretha (1908–1995), Isabella (1914–2008) and Stefanie von Papen (1919–2016 ). Antoinette von Papen had been married to the lawyer and civil servant Max von Stockhausen since 1926 , while Isabella von Papen was engaged to Wilhelm Freiherr von Ketteler , a close colleague of von Papens who was murdered by the Gestapo in 1938.

Military attaché in Washington (1913–1915)

In 1913, von Papen became an army attaché at the German embassy in the USA . He was responsible for the USA and Mexico . He owed this diplomatic post above all to his father's good relations with Kaiser Wilhelm II , with whom he had studied together. In the United States, he met numerous personalities from political and public life, who at the time held subordinate management positions, but later moved up to the top state positions at around the same time as himself, such as Franklin D. Roosevelt or Douglas MacArthur , whom he had during the turmoil helped escape Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution of 1914. During the First World War , the double post in Washington and Mexico was of great political importance, which von Papen had not grown.

He became conspiratorial in the USA , which was in complete contrast to his mission as a military attaché and tried to bring about a German-friendly attitude in Mexico. Together with Karl Boy-Ed , the German naval attaché and Heinrich Albert , the German commercial attaché , von Papen built an espionage and sabotage ring in New York City. This group, active in the secret service, distributed, among other things, forged passports of neutral states to German army reservists who were staying in the United States to enable them to enter Germany through the British naval blockade . They supplied German ships in the Pacific from San Francisco with supplies and reported the departure times and loads of US ships to Berlin. Von Papen had advertisements printed in American newspapers expressly warning American citizens against traveling on British ships on behalf of the German embassy. In the latter case, von Papen was linked to the sinking of the RMS Lusitania .

The front company "Bridgeport Projectile Company" founded by him in Connecticut had the task of overloading the production capacities of those American industrial companies that manufactured goods for the European theater of war with "private orders" to such an extent that no more capacities should be free for the Entente states to manufacture weapons, ammunition and similar war-related goods. For example, he tried to buy up all of the toluene resources in the USA in order to make TNT production in America impossible. In December 1915, several people in this group, including Franz von Papen, were charged by a court with conspiratorial activities in the United States.

The accusation that he was responsible for planning the 1916 demolition of Black Tom Island , the most important transshipment point for munitions from the United States to Europe, was vigorously denied by von Papen throughout his life, as early as the early 1950s Letter to the editor to Time magazine.

Overall, he made a few mishaps in his work, which led him to Mexico, among other places, so that he was expelled from the country in January 1916. On his way home, thanks to a diplomatic passport , he was able to pass the British naval blockade with a clear escort and thus reach German soil. Von Papen's belief that his person's diplomatic immunity would also apply to his luggage, however, was not fulfilled: During his control by the British Navy, all documents that he carried with him were stripped from him, so that the British took possession of more Secret information came in and identified numerous members of Papen's American agent group through receipts, account books and similar data, resulting in a series of arrests.

War participation

After his return to Germany, von Papen was awarded the Iron Cross by the Kaiser and then made available to the German Army . During the First World War, he initially served as a battalion commander on the Western Front . Later he was a general staff officer in the Middle East , then a major in the Ottoman army in Palestine . During his activity there on Erich von Falkenhayn's staff , he met Joachim von Ribbentrop , an acquaintance who was to be of great importance for the political processes in Germany at the beginning of 1933. It was only through Ribbentrop's intercession with Adolf Hitler in favor of Papens that he succeeded in dispelling his initially hostile attitude towards the reactionary Catholic aristocrat and in making him an alliance of convenience. On the way home to Germany von Papen made another important acquaintance, that of Paul von Hindenburg .

Life in the Weimar Republic

After the German defeat, von Papen resigned from the military as a lieutenant colonel in the spring of 1919 . He couldn't cope with the collapse of the German monarchy in his life, and so he didn't want to serve in a republican army. Franz von Papen settled in Dülmen in the Münsterland that same year and lived in the Merfeld house until 1930 . He began to become politically active and was initially a member of the Prussian state parliament from 1921 to 1928 for the constituency of North Westphalia . As a board member of the Westphalian Farmers' Association and other agricultural associations, he represented the agricultural interests of his constituency and the monarchist wing of the Catholic Center Party . There were strong tensions between him and the republican-democratic left wing of the Center Party, which dominated the Center Party during the early years of the Weimar Republic. Von Papen's worldview was based on conservative Christianity, and his long-term policy was to restore a Christian and conservative authoritarian monarchy. He condemned the party leadership of the Center for Cooperation with the “atheist” SPD and “rationalist” left-wing liberalism. In the 1924 state election campaign, von Papen became involved against the grand coalition in Prussia consisting of the center, SPD, DDP and DVP . Instead, he demanded the formation of a “ citizens' bloc government ”, ie the replacement of the SPD by the DNVP . His spectacular appearance during the handling of several motions of no confidence against Prime Minister Otto Braun (SPD) caused a general sensation in the press. Furthermore, von Papen refused to support the candidate of his own party, Wilhelm Marx , in the 1925 presidential election and instead publicly supported the election of Paul von Hindenburg . The center then wanted to exclude him, but in the summer of 1924 von Papen had acquired a significant stake in the party newspaper Germania and was elected chairman of the supervisory board the following year , which gave him a journalistic locking bar. In the period between 1928 and 1930, von Papen concentrated his political activities on various conservative organizations, such as the German Men's Club . In 1930 he moved to the property of his in-laws in Wallerfangen on the Saar. In the same year he moved back into the Prussian state parliament, to which he was a member until April 24, 1932. In this function he continued to demand the end of the grand coalition in Prussia and an alliance between the center and the DNVP.

Plans for an anti-communist alliance

Papen was a close friend of the industrialist Arnold Rechberg, known for his anti-Soviet plans . On July 31, 1927 von Papen wrote to the central politician and member of the supervisory board of Deutsche Bank Hans Graf Praschma :

"[It] seems to me that one thing is most urgent in European politics: the elimination of the Bolshevik source of fire"

In a reply letter dated August 12, 1927, Prashma expressly agreed. On June 10, 1932, ten days after von Papen had become Reich Chancellor, he was part of the German Herrenklub , which included 100 leading industrialists and bankers, 62 large landowners and 94 former ministers, in the presence of the leading National Socialists Hermann Göring , Ernst Röhm and Joseph Goebbels gave a speech in which he presented his project to a Franco-German coalition directed against the Soviet Union and called for all states to join forces under the slogan “Death to Bolshevism”. In several discussions with French politicians, von Papen made his offer of an anti-Soviet alliance. His plans failed, however, and the Soviet government was informed of von Papen's activities by the French.

Chancellor

Succession to Brüning

On June 1, 1932, at the instigation of his old friend Kurt von Schleicher , Papen was appointed Reich Chancellor by Reich President Paul von Hindenburg as successor to Heinrich Brüning . The appointment initially caused astonishment among the German public, in which Papen was largely unknown at the time. Extensive historical considerations have since been made about Schleicher's motives for proposing Papen. Schleicher's friend Werner von Rheinbaben summarized his presumed motivations in 1965 in the following way:

“[The considerations] went as far as to propose a man for chancellor who fulfilled three conditions: He had to lie to Hindenburg, i. H. his origin and way of thinking would be acceptable to him, because only such a chancellor could hope from now on with the simple way of thinking of the self-confident Reich President, to get his signature on the more and more substantive drafts based on Article 48 of the constitution. According to Schleicher's illusion, the new man should also meet the requirements of Nazi support. Third, he should be able to be in close contact with him; H. So to rule according to Schleicher's ideas. "

During his entire term of office, Papen governed with the emergency ordinances of the Reich President and - a hallmark of every presidential cabinet - was dependent on his consent.

Forming a Government: The "Cabinet of National Concentration"

After his appointment, von Papen formed a minority government from non-party ministers and members of the DNVP , which was called the “Cabinet of the Barons” because seven of the twelve members of the government were nobles. He anticipated his expulsion from the Center Party by resigning on June 3, 1932.

Papen's program of a "new state"

The new government, which was purely a presidential cabinet with no prospect of parliamentary majorities, sought a thorough constitutional reform, for which the name “The New State” has become common. That was the title of a brochure published in autumn 1932 by the right-wing conservative journalist Walther Schotte , for which von Papen had written a foreword. Anti-democratic ideas were summarized here that had previously been discussed in the circles of the German men's club and that took up the ideas of various right-wing intellectuals such as Arthur Moeller van den Bruck , Carl Schmitt or von Papen's later speechwriter Edgar Jung . In essence, it was about changing the constitution to transform the Weimar Republic from a parliamentary to an authoritarian- presidential republic. The office of the Reich President was to be merged with the newly created office of a Prussian State President; By changing Article 54 of the Weimar Constitution , the Reich government should no longer depend on the confidence of the Reichstag , but only on that of the Reich President; the influence of the Reichstag was to be further diminished by changes in the electoral law and the creation of a second chamber, which would not result from elections. At the end of the constitutional reform, according to von Papen, the re-establishment of the monarchy should come. However, there were no clear ideas about the way in which this ambitious program could be realized, which actually required a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag to change the constitution, which was unattainable for von Papen's minority government.

Tolerance alliance with the National Socialists

In order to stabilize the new government, Reichswehr Minister Schleicher in particular felt it was necessary to win Hitler's NSDAP for a support course. In the long term, the party could then be “tamed” through government participation and incorporated into von Papen's course. Therefore, even before Brüning's fall, he had established contact with the leaders of the National Socialists. They agreed to tolerate von Papen's government under two conditions: firstly, there should be new elections, secondly, the ban on the SA and SS imposed under Briining must be lifted. The new government complied with both requests: on June 4, 1932, the Reich President dissolved the Reichstag, and on June 16, 1932, the SA ban fell. The result was an unprecedented wave of political violence during the election campaign.

New situation in Prussia after the victory of the NSDAP in state elections

In the Prussian state elections on April 24, 1932, the ruling parties of the government coalition (consisting of the SPD, DStP and the center), which had been in power since 1920, lost their parliamentary majority due to the high election victory of the NSDAP - other coalitions were not possible. It was therefore necessary to resort to the solution already applied in other German states: the old state government was retained as the "managing" body. Von Papen wanted a coalition of center and right for Prussia, which is why he initiated talks about a possible cooperation between the NSDAP, the German nationalists and the center - but these failed because of the NSDAP's claim to totality. Thereupon von Papen envisaged two possibilities: The first consisted in the implementation of a long-debated imperial reform that would dissolve the Free State of Prussia .

Plan of the "Prussian Strike"

Because this path would only lead to the goal in the medium term, von Papen chose the alternative of deploying the Reichswehr in Prussia, having himself appointed Reich Commissioner and thus bringing the largest German country under his control. Reich President Hindenburg signed an emergency ordinance on July 14, 1932, which appointed von Papen as Reich Commissioner for Prussia and authorized him to depose the incumbent Prussian government because "public security and order" in Prussia was endangered and had to be restored. Hindenburg did not set a date - von Papen was able to put the emergency ordinance into force at a time that seemed appropriate to him. Von Papen chose July 20, 1932 as the date of implementation. The civil war-like clashes of the Altona Blood Sunday of July 17, 1932, served as a pretext. The dismissal of the incumbent state government is known as the " Prussian Strike ". The government claimed to be based on the constitutional instrument of a Reich execution , as it had been carried out before under Reich President Friedrich Ebert against Saxony and Thuringia.

Lausanne Conference

During these days, von Papen and important ministers in his cabinet were mostly not in Berlin, but in Lausanne , where the Lausanne Conference met from June 16 to July 9, 1932 . Here von Papen wanted to push through the cancellation of the German reparation obligations that his predecessor Brüning had publicly called for since January 1932. Due to Germany's insolvency during the global economic crisis , the reparations had not been paid since 1931. Von Papen, who was not very experienced internationally and sometimes acted inappropriately, achieved this goal with the support of the conference chairman, British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald , but with one caveat: a final sum of three billion gold marks was agreed, the payment of which was deferred to the German Reich. Von Papen's hope that this foreign policy success would have a positive impact on his government in the elections was deceptive: the entire German press unanimously disapproved of the fact that he had not been able to push through a complete cancellation of the reparations. Particularly sharp attacks came from the part of the NSDAP, an indication that it was not at all willing to keep its promise of tolerance.

Break of the NSDAP with von Papen after the election victory on July 31, 1932

The National Socialists' break with von Papen came after the NSDAP's victory in the Reichstag elections on July 31, 1932 . The party doubled its seats and ousted the SPD as the strongest force in parliament. Together with the KPD , it now had a “negative majority”, which made any meaningful work of parliament illusory. In explorations with members of the Papen government, Hitler uncompromisingly demanded the chancellorship and various key ministries for coalition participation. When this was refused by Hindenburg, he gave up all support for the Papen government.

Motion of no confidence and dissolution of the newly elected Reichstag on September 12, 1932

As a representative of the now strongest party, Hermann Göring was also elected President of the Reichstag by the democratic center . When the newly elected Reichstag met on September 12 and wanted von Papen to make his government statement, the KPD requested that the agenda be changed and that suspicion of the government be discussed immediately. Göring deliberately overlooked the Reich Chancellor's request to speak, who wanted to dissolve the Reichstag immediately under Article 25 of the Reich Constitution, and put the KPD's motion to a vote, which ultimately found an overwhelming majority. The vote was invalid, however, because von Papen had simultaneously placed the Reich President's dissolution order on Goering's desk and new elections had to be announced. However, the political signal turned out to be devastating for the government's reputation, with 9/10 of all MPs voting against it (512: 42).

Last support for von Papen

Von Papen's cabinet received public support only from the DNVP and the now marginalized DVP, as well as from large-scale industrial circles who strongly supported the Chancellor's authoritarian utopias. The majority of their donations went to von Papen and his support groups in the second half of 1932; in autumn 1932, a DNVP-affiliated “German Committee” called for the government under the heading “With Hindenburg for people and empire!” Papen and thus spoke out against the NSDAP, signed by numerous large industrialists. Prominent names like Ernst von Borsig , the chairman of the mining association Ernst Brandi , Erich von Gilsa , Fritz Springorum and Albert Vögler could be read here .

Reichstag elections on November 6, 1932 and plans to eliminate parliament

The Reichstag elections of November 6, 1932 resulted in significant losses for the NSDAP, but gains for the DNVP, the only major party to support the Reich Chancellor. But the KPD was also able to grow, the two radical parties retained their blocking majority. The Reichstag was thus still paralyzed. The SPD and the center turned down a coalition offer from Papens for different reasons. Von Papen and his Interior Minister Wilhelm Freiherr von Gayl now planned to suspend the constitution and postpone new elections for an indefinite period in order to shut down parliament for at least half a year. In the end, there could be a constitutional amendment legitimized by a referendum, which should bring about the desired restructuring of the state. This policy was supposed to be supported by the Reichswehr , which was supposed to nip the expected resistance from leftists and National Socialists in the bud.

Failure of Papens with his plan of overthrow, Schleicher's split plan

Hindenburg initially agreed to the plan, but Reichswehr Minister Schleicher opposed it and, with the help of the Ott business game , convinced the other cabinet members to renounce such plans and instead focus on a split in the NSDAP. Von Papen tried in vain to get Hindenburg to replace the Reichswehr Ministry before the Reich President, who shied away from the risk of civil war, finally dropped his “favorite Chancellor” on December 3, 1932 and replaced it with Schleicher.

Von Papens economic policy

In terms of economic policy, the von Papens reign was marked by a departure from the dirigistic and deflationary goals of the previous government. In late summer, the government passed an emergency ordinance on a state economic stimulus program that tried to stimulate the economy by making it easier for the private sector. Measures to rehabilitate the budget had already been decided beforehand, mainly by cutting social spending, which further exacerbated the social situation in the country. The initial economic policy initiated by his cabinet, which had set in motion a modest job creation program and pointed a first way out of the crisis, led to an incipient decline in unemployment figures. The plans to increase the motorway construction and to create a conscription army had to stay in the drawer for the time being, as their implementation was not possible until December 1932 due to restrictions of the Versailles Treaty . Hitler later resorted to these plans.

Period of National Socialism (1933–1945)

Initiation of the Hitler government

On January 4, 1933, Papen's meeting with Hitler took place in the house of the banker Kurt Freiherr von Schröder , where the NSDAP's participation in government was discussed. State Secretary Otto Meissner and Oskar von Hindenburg also took part in a later meeting on January 22nd . All three confidants of Paul von Hindenburg are credited with convincing the Reich President of the appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor in the last days of January . Von Papen's plan was to “frame” Hitler, buy him and his votes, and in reality exercise power himself. He is said to have said: "In two months we will have pushed Hitler into the corner so that he squeaks!"

Von Papen as Vice Chancellor of Hitler (1933–1934)

As early as February 1933, von Papen largely disempowered himself by persuading Hindenburg to sign the so-called "Reichstag Fire Ordinance " submitted to him by Hitler immediately after the Reichstag fire on February 28 , which Hitler in combination with the Enabling Act of March 24, 1933 a almost dictatorial position bestowed, which this could fully exploit. Hindenburg's own position, the position of the Reich President, whose trust was ultimately von Papen's only real basis of power, was thereby considerably weakened.

For the election campaign for the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , von Papen teamed up with DNVP boss Alfred Hugenberg as well as Franz Seldte and Theodor Duesterberg , the leaders of the Stahlhelm Front Soldiers , in the list association Combat Front Black-White-Red , founded on February 11, 1933 . During the election campaign, von Papen made particular efforts to persuade non-party conservatives and conservative Catholic voters who had previously chosen the center to vote for the frontline. In von Papen's election speeches - which borrowed numerous words from the vocabulary of the Conservative Revolution - of February and March 1933, the influence of the writer Edgar Jung , who had entered the service of the Vice Chancellor as advisor and speechwriter at the beginning of February 1933, was first visible. On election day, the fighting front was able to unite 8% of the votes cast. In the first Reichstag of the Nazi era, she had 52 seats. Von Papen's share in the already very limited success of the conservative collection list has been estimated in research as rather low. However, his campaign speeches were conceded to have been an “essential asset” on the front line.

In the months after the Reichstag election, von Papen's position in power politics in Hitler's cabinet quickly eroded in favor of the National Socialist wing of government: on April 7, he had to take over the position of Reich Commissioner for Prussia, which should have been his most important power base in the joint government alongside the vice-chancellor In 1933 he ceded to Hermann Göring, who was introduced to the re-established office of Prussian Prime Minister at that time . As a result, von Papen tried to create a new base in the course of 1933, hoping in particular to be able to unite the forces of Catholic conservatism and politically independent legal circles, especially the younger generation, behind him. For this purpose he created decidedly Catholic-conservative rescue organizations, which, in the words of Joachim Petzold, “could be viewed as a form of resistance to the Nazi omnipotence”. In fact, they served von Papen's illusory mission to build a bridge between Catholicism and National Socialism. It all started with the Association of Catholic German Cross and Eagle (BkD), which von Papen had founded in March 1933. In this he took over the patronage, while personal confidants of his (first Emil Ritter , then Roderich von Thun ) took over the daily organizational work as general secretary. After the federal government failed to achieve the political weight it wanted, von Papen converted it into a so-called Working Group of Catholic Germans (AKD) in October . Count Thun was reappointed General Secretary. In a letter to the German ambassador to the Holy See in Bergen, von Papen saw the purpose of the AKD as “promoting understanding for the Nazi movement and its great historical tasks.” According to the presentation of the Nazi party leadership of the NSDAP in September 1934 "Contributed effectively to a reconciliation in the areas assigned to her" and was dissolved. At the same time, Edgar Jung, who as the founder of the Young Academic Club had relevant experience, as well as von Papen employees Wilhelm von Ketteler and Friedrich-Carl von Savigny tried to win over the student youth for the conservative Fronde around von Papen. Accordingly, they often had von Papen give speeches to students who were influenced by the ideas of the Conservative Revolution , and they launched confidants from the group around von Papen, such as Edmund Forschbach or Savigny themselves, to positions of influence in organizations in which the conservative student body was bundled. Furthermore, in the Reichstag election of November 1933 , they succeeded in smuggling some men who did not belong to the NSDAP as members of the National Socialist Reichstag, to whom Edgar Jung assigned the task of a secret opposition on hold. However, all these measures could not prevent von Papen from falling into an "almost ridiculous figurehead" (Heinz Höhne), at least in public perception in the course of 1933.

In July 1933, von Papen, as the representative of the Reich government, concluded the so-called Reich Concordat, which is still valid today and regulates the relationship between the German state and the Catholic Church . The end of political Catholicism was sealed with the treaty. The Nazi regime not only arbitrarily interpreted the contract, negotiated in a hurry and under pressure, but also violated it to an increasing extent in the years that followed.

During his time as Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen became a founding member of the National Socialist Academy for German Law Hans Franks .

In connection with the approaching death of Hindenburg, von Papen tried in vain in the spring of 1934 to obtain a will from his hand in which the restoration of the monarchy should be publicly recommended. In the now famous Marburg speech he warned: “Germany must not become a blue train!”. Hindenburg then sent him a telegram of congratulations. The speech did not mean “early resistance from later insight” (Benz). Von Papen castigated excesses of the Nazi regime in the form of SA attacks and Goebbelian rhetoric, but did not criticize Hitler. During the suppression of the so-called " Röhm Putsch ", von Papen was under house arrest on Göring's instructions and survived the massacre. The murder of his close collaborators Herbert von Bose and Edgar Julius Jung , who wrote the Marburg speech, did not prevent him from continuing his collaboration with the regime after he left the office of Vice Chancellor in July. In the same month he went to Vienna as Hitler's special envoy to smooth the diplomatic waves that had arisen after the murder of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss by members of the Austrian branch of the Nazi party.

Diplomat in the service of Hitler (1934–1944)

Head of a special mission on behalf of Hitler

From 1934 to 1938 von Papen served as envoy and from 1936 as ambassador of the German Reich in Vienna. Due to a special agreement between him and Hitler, he was not integrated into the apparatus of the Foreign Office during this time, but as head of a special mission directly subordinated to the dictator ( immediate relationship ).

Preparation of the connection to Austria

During his three and a half years of service, von Papen prepared the connection of Austria to the German Reich. He was unexpectedly recalled from Vienna on February 4, 1938, the day of the change at the head of the Wehrmacht ( Blomberg-Fritsch crisis ), a few weeks before Austria was annexed to the German Reich. The murder of his close colleague and potential son-in-law Wilhelm Freiherr von Ketteler by the SD , immediately after the invasion of the German armies, did not prevent von Papen from accepting the NSDAP golden party badge , which he was given for his services to the “Anschluss” . In addition to the party badge, von Papen also accepted membership in the NSDAP (membership number 5.501.100; admission date August 13, 1938).

Ambassador in Ankara: New Europe and peace actions

After Austria's successful annexation , von Papen continued to make himself available to the Nazi regime with the title of Ambassador for special use from the spring of 1938 . At the end of April 1939 he took over the post of ambassador in Ankara , which he said he had rejected several times to the new Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop . The increased importance of Turkey after the occupation of Albania by Mussolini at the beginning of April 1939 finally spoke in favor of accepting the post. Unlike in Vienna, in Ankara von Papen was subordinate to the Foreign Minister and not to Hitler, whom he visited more than a dozen times for talks. Following the instructions of Berlin, von Papen tried in vain in Ankara to dissuade Turkey from its “active neutrality” and to win it over to a “New Europe” under the leadership of the German Reich. In parallel to his loyally pursued official business, von Papen undertook a large number of peace initiatives from the beginning of the Second World War and up until the spring of 1944 and sought mediators with the allies and neutrals.

When von Papen left the ambassador's residence in Ankara on February 24, 1942, a bomb exploded right next to him. But he was unharmed. It was not until five decades later, after a review of Soviet archives, that details became known: The Soviet secret service NKVD was behind the attack . One of the assassins was the emigrated Russian writer Mark Levi, who had published under the pseudonym M. Agejew in Paris emigrant publishers. After the attack he was able to escape to the Soviet Union, while a Soviet diplomat who was also involved in the attack was arrested by the Turkish authorities.

Through intermediaries, he secretly maintained contacts with the Istanbul-based US naval attaché George H. Earle , as both later stated in their autobiographical writings. Earle, a long-time political companion and confidante of President Franklin D. Roosevelt , who maintained contacts with the resistance movements in the Balkans from Istanbul, campaigned in vain for the German resistance movement against Hitler.

His so-called "peace operations" failed because of the distrust of potential mediators who had doubts about von Papen's legitimacy, as well as because of interviews that he gave to media representatives in individual cases out of profile addiction. In 1941 von Papen concluded the German-Turkish friendship treaty with the Foreign Minister of the Republican People's Party (CHP) of the Turkish founder Ataturk , Şükrü Saracoğlu .

Von Papen is listed on the 400-name " List of Key Nazis " that John Franklin Carter , adviser to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt , had compiled in 1942 for the White House and also for military intelligence OSS forwarded.

Ambassadorial activity and the Vatican

One year after von Papen's assumption of office in Ankara, Ribbentrop tried to transfer the incalculable ambassador to the less important Vatican representation in Rome. Pope Pius XII consulted the Berlin Bishop Count von Preysing in the run-up to the Agrémenter request, who confirmed reservations from Rome on the grounds that the "type of a high-ranking Catholic National Socialist would somehow appear to have been sanctioned by the church." With the delegate of the Vatican in Istanbul, Angelo Roncalli , the later Pope John XXIII., von Papen maintained close contact until the end of his service in Turkey in August 1944. He found out from him early on about the extermination of Jews in Poland. Contrary to his own statements, von Papen did not support any of Roncalli's numerous rescue operations in favor of Jews from the Nazi-occupied states. After Turkey broke off diplomatic relations in early August 1944, von Papen returned to Germany. He received the Knight's Cross for War Merit Cross from Hitler's hands in mid-August for his diplomatic mission in Turkey.

Escape and arrest

After his last meeting with Hitler in August 1944, von Papen fell into the vortex of military defeat. Before the approaching Allies he fled first to his farm in Wallerfangen in the Saarland and then to the property of his son-in-law Max von Stockhausen in Stockhausen near Meschede . On April 10, 1945, von Papen was arrested by US soldiers a few kilometers from Gut Stockhausen in the hunting lodge of his son-in-law.

Post-war period and old age (1945–1969)

In 1945, his hometown Werl withdrew his honorary citizenship, which was granted in 1933 . In 1946 he was acquitted in the Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals . On February 24, 1947, he was classified as the "main culprit" in a ruling chamber procedure in the context of denazification and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp; the years spent in detention since 1945 counted towards his sentence.

In 1949 he was released early and the ordered property confiscation was reversed. In the following years he lived in Benzenhofen Castle in the Upper Swabian municipality of Berg and tried unsuccessfully a new political career. His long-term efforts to get pension payments in recognition of his diplomatic and military service failed because of his close connection to National Socialism (Foreign Office) and because of culpable violations of the rule of law (Administrative Court of Baden-Württemberg).

Von Papen died on May 2, 1969 in Obersasbach and was buried in the Niederlimberg community cemetery in Wallerfangen .

Autobiographical and contemporary works

In the years after his release from prison, von Papen wrote, among other things, his autobiography The Truth One Alley (1952) and The Failure of a Democracy (1968).

Both books were sharply criticized by historians because von Papen's account played down his role in the failure of the Weimar Republic. Theodor Eschenburg (1904–1999) criticized his “childlike, primitive conception of politics” in 1953 and summed up: “Vanity and political talent are inversely related”.

Evaluation by contemporaries and posterity

After the formation of the “Papen Government” in May 1932, Kurt von Schleicher wanted, as he told journalists, to see nothing more than “a hat” in the new Chancellor, which he, Schleicher - as the actual head of the “Papen Government” - would sit on his own head. In the same year, this assessment turned out to be a major political miscalculation: "Fränzchen", as Schleicher von Papen mockingly called it in private, not only managed to escape the general's control and take his own course contrary to Schleicher's plans but he also succeeded in overtaking Schleicher in favor of the aged Hindenburg.

Hitler initially saw von Papen as a rival for power. After he had been eliminated, he paid him tribute: In 1942 he saw his great “merit” in the fact that he “broke into the holy constitution” in 1932 when the Prussian state government was deposed, and thus the first step towards eliminating the “Weimar Systems ”would have done. Hindenburg, who - according to Sebastian Haffner - is said to have found his "ideal of masculinity" in von Papen "late in life", expressed his close ties with von Papen when he gave him a picture of himself in December 1932 with the dedication " I had 'a comrade '. Hitler later claimed that Hindenburg was "very fond of" von Papen, but also saw him as "a kind of greyhound". The former Minister of Economics, Hans von Raumer , said in 1963 that von Papen had mastered the " serenity tactics " with which the men around the Reich President had influenced him best and thus had a disastrous influence on the "substitute monarch". Von Papen must therefore be seen as the “main culprit” for the fatal decisions made by the head of state in 1932/1933.

Hans-Otto Meissner , who - as the son of Hindenburg's closest colleague Otto Meissner - was able to observe von Papen up close, judged that he was "in no way prepared for the high office". From a human point of view, von Papen appeared to him to be "particularly unappealing". Likewise, the father “absolutely couldn't stand Herr von Papen from the first moment”. In addition, he was “extremely in need of approval”: “You got the impression that it was very important to him to be noticed from the first minute of his appearance to the last.” “I never forget the expression on his face, it was the smugness in person, as to whisper around. The raised eyebrows, the slightly bent posture and his condescending look at other people are unforgettable to me to this day. ”Incidentally, von Papen was“ actually, as his opponents always claimed, the type of gentleman rider: it was purely outwardly absolutely right. But the word concept went further, according to popular opinion in the Herrenreiter one saw a haughty, hollow-headed, blasé and also noble rider. He rode across his own lands with his shoulders sagging. As it was said in a mocking song of the time, he had no other interests than [...] horses, champagne and women. "

Fritz Günther von Tschirschky , who from 1933 to 1935 used his position as an employee of von Papens without his knowledge to fight against National Socialism , judged a little more mildly - but still negative - in retrospect of his boss:

“Papen's actions were never deliberately malicious, even if many of his actions were incomprehensibly ambiguous and, unfortunately, I have to say it, resulted from irresponsible superficiality. He was a man with the qualities of a young cavalry officer who can overcome many hurdles that others find insurmountable obstacles. But he was unable to maintain the direction he had taken for any length of time. He also had the qualities of a trained general staff, those of a diplomat and old-school nobleman, and those of a devout Catholic. However, all these properties were not connected to a healthy harmony in him, but were, so to speak, in separate departments next to each other. That's why his picture was so distorted. For many he was considered cunning, lying and irresponsible, for others as capable and responsible. [...] I had to find out [every day anew]: who is sitting at the desk today: the young cavalry officer, the diplomat, the Catholic? Depending on which Papen was sitting there, I presented. "

In addition, Tschirschky noticed that he often had to observe how suggestions he had made turned into the opposite due to von Papen's rash actions. By himself and his “surely pure intentions”, he did not even notice “the damage he often caused by his egocentric, superficial actions”. Konrad Adenauer , who was a “party friend” von Papens in the Center Party in the 1920s until his resignation, made a similar statement to an acquaintance shortly after the Second World War. He wrote that as early as the 1920s he saw von Papen as a boom who irresponsibly subordinated everything to the goal of playing a personal role. Von Papen's predecessor as Chancellor, Heinrich Brüning , briefly called him “irresponsible”.

Papen's rejection on the political left was even more decisive: the writer and publicist Kurt Tucholsky saw Papen's government as “an ancien regime of the worst kind”. The journalist Alfred Polgar, on the other hand, in the late 1930s, in a gloss entitled Der Herrenreiter, passed a devastating judgment on von Papen, whose “lack of character in history” is established because: “The fundamental principle of all his attitudes is: none to have. His personal political credo is: stay up at all costs. His motto: I serve ... no matter who. "

In the non-German press and literature in the 1930s and 1940s there was initially a tendency to demonize von Papens. The characterization of Papens as a “master spy” and “unscrupulous intriguer” was almost a leitmotif. In 1941, for example, the American Time Magazine identified him as an elegant diplomat who was in all respects a “Prussian image” of the British Foreign Minister at the time, Anthony Eden - “with the exception of his [lack of] integrity”. The Hungarian Tibor Kövès titled his Papen biography, published in the same year, committed to the same idea, Satan in Top Hat ("Devil with a top hat ").

Judgment by historians

The majority of historical research paints an extremely negative picture of the person and work of von Papen. Winged words, which are used almost formulaically when he is mentioned, are two mocking names that call him “Herrenreiter” and “Hitler's stirrup holder”. The accusation contained therein that von Papen was primarily responsible for Hitler being able to take the last step to power is still held by the majority of historians today. The Papen biographer Joachim Petzold declares von Papen as “A German Doom” in the subtitle of his study. Karl-Dietrich Bracher described him in a Spiegel review as the “murderer of a democracy”. The bottom line is:

If something teaches something, it is the bankruptcy of the conservative-authoritarian and nationalist state ideology. That may be a warning in the country of Axel Springer and the NPD.

Other researchers see him primarily as a short-sighted reactionary and a political dilettante . For example, the thesis was put forward that the numerous diplomatic clumsiness that the inexperienced von Papen underwent during the reparation negotiations in Lausanne made an agreement possible in the first place because they weakened the German negotiating position. Richard Rolfs programmatically compares von Papen in his biography with the literary figure of the sorcerer's apprentice , who, in vain overconfidence, conjures up forces that are beyond his control.

Historians have judged Papen's character as critically as his contemporaries, even from a distance of decades. Joachim C. Fest, for example, who portrayed him as a typical representative of the conservative collaboration with the Nazi regime, attested Papen “moral insensitivity, a fundamental lack of intellectual honesty and that allure, shaped by class consciousness, that dealt with the truth like the gentleman with the staff. ” Golo Mann , on the other hand, found the situation of 1932/33 above all to be thought about: “ That a person of such featherweight could make world history and make decisions for a brief moment. ” At the same time, Golo Mann also admitted that Papen “ did not bad, not malicious basically “ , but just as vain, scheming and superficial. He would also have had the courage to ban the greatest threats to the Weimar Republic, namely the extreme parties on the right and left, but at the cost of a state of emergency and the use of the army. Ultimately, however, Papen in his chancellorship had “spoiled too many and won too few”. Golo Mann therefore paints a rather differentiated picture overall.

With the Americans Henry Mason Adams and Robin K. Adams , von Papen also found two passionate defenders who wanted to see him as a “rebellious patriot”. Friedrich-Karl von Plehwe sees von Papen as an unlucky figure and emphatically criticizes him for his behavior in December 1932 / January 1933 and for his failed policy as Chancellor in the summer and autumn of 1932, but he is against the leitmotif of the Herrenreiter label , the he deemed arbitrary and unjust.

Memberships and church honors

Von Papen was a member of the Order of Knights of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and Knight of the Order of Malta .

In 1923 Pope Pius XI appointed him . to the papal secret chamberlain . This appointment was made in 1939 by Pope Pius XII. not confirmed because von Papen had neglected to submit a corresponding application. In 1959 Pope John XXIII repeated but the appointment. The later Pope John XXIII. was known during his time in Ankara (1934–1944) as the Apostolic Legate for Turkey and Greece with von Papen.

estate

After the Second World War, von Papen himself assumed that his private archive in his apartment in Berlin's Lennéstrasse had been a victim of the bombing war and had been completely destroyed. In fact, at the end of the war, a large number of files were found by the Red Army and taken to the Moscow special archive set up to hold German booty files. The existence of this von Papens estate, comprising more than eighty files, was not known until the early 1990s. On the basis of the Moscow files, numerous misleadings and false assertions have since been found in von Papen's memoirs. During a state visit in the 1990s, then Russian President Boris Yeltsin presented the then German Chancellor Helmut Kohl with microfilms of the estate of Walter Rathenau from the Moscow Special Archives, including copies of nineteen files from the Moscow Papers estate, which are now held N 1649 are kept in the Federal Archives. Some particularly sensitive files from von Papen's Moscow estate - including a copy of the otherwise lost original will of Paul von Hindenburg from 1934 - were handed over to the archives of the then Soviet Foreign Ministry in the 1950s. After that, their track is lost. Today these documents are considered lost.

Another part of Papens' estate is in the possession of the French National Archives. This consists of documents that he kept on his Wallerfangen estate until 1944 and hidden in the basement of Gemünden Castle shortly before the end of the war, where they were discovered by the French occupation authorities in autumn 1945.

various

At the beginning of December 2019, Papen's tombstone was stolen and placed in front of the CDU party headquarters in Berlin on December 7, 2019, the artist collective Center for Political Beauty confessed to the act. The act is ideologically and temporally related to the nationally and internationally predominantly criticized action "Sucht nach uns!", In which the collective set up the ashes of Holocaust victims in a column in front of the Reichstag building in Berlin.

Fonts

- Appeal to the German conscience. Speeches on the national revolution . Oldenburg 1933.

- Appeal to the German conscience. Speeches on the national revolution. New episode . Oldenburg 1933.

- The entrepreneurial personality in the new state . Berlin 1934.

- One alley for truth , Munich 1952.

- Europe, now what? Reflections on the politics of the Western powers . Goettingen 1954.

- Some comments on the book "Reichswehr, State and NSDAP", "Contributions to German History 1930–1932" by Dr. Thilo Vogelsang . o. O. 1962.

- How Weimar died: reasons and backgrounds for the overthrow of the 1st republic. Exclusive interview with Franz von Papen, former Reich Chancellor D., on the prehistory and the final months of the Weimar Republic , 1983. (Transcript of an interview with von Papen from 1962, edited and edited by Hendrik van Bergh )

- The failure of a democracy. 1930-1933 . Mainz 1968.

literature

Source editions:

- Karl-Heinz Minuth (arrangement): The von Papen cabinet, June 1 to December 3, 1932 , 2 vols. Boppard am Rhein 1989.

- André Postert, Rainer Orth: Franz von Papen to Adolf Hitler. Letters in the summer of 1934 . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 63, 2015, no. 2, pp. 259–288.

Biographies

- Henry Mason Adams , Robin K. Adams: Rebel Patriot. A Biography of Franz von Papen . Santa Barbara 1987. (Review by George O. Kent under the title: Problems and Pitfalls of a Papen Biography in: Central European History 20 (1987), No. 2, pp. 191–197. 1st page online)

- Reiner Möckelmann : Franz von Papen. Hitler's eternal vassal . From Zabern-WBG, Darmstadt 2016. ISBN 978-3-8053-5026-6 . (Review by Sebastian Weitkamp : Self-deceiver and Lügenbaron . In: FAZ of November 8, 2016, p. 8, online here [1] ; Review by Karl Heinz Roth : "Franz von Papen. Hitler's eternal vassal", In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 65 (2017), no. 5, p. 484).

- Rainer Orth : "The official seat of the opposition"? Politics and state restructuring plans in the office of the Deputy Chancellor in the years 1933–1934 , Böhlau, Cologne 2016. ISBN 3-412-50555-2 (Review by Daniel Koerfer : Franz von Papen 1933/34. Vice Chancellery group against Hitler . In: FAZ of April 4, 2017; Review by Larry Eugene Jones : "The official seat of the opposition?" In: Central European History , 50, Heft 2, pp. 285–286).

- Joachim Petzold : Franz von Papen. A German fate . Buchverlag Union, Munich, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-372-00432-9 . (Review by Wolfgang Elz : Always worse prevented . In: FAZ of December 29, 1995)

- Richard W. Rolfs : The Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Life of Franz Von Papen . 1996.

Short biographical sketches

- Bernd Braun: The Weimar Chancellor. Twelve résumés in pictures . Droste, Düsseldorf 2011, ISBN 978-3-7700-5308-7 , pp. 406-439.

- Ernst Deuerlein : Franz von Papen , in: Ders .: German Chancellor. From Bismarck to Hitler . Munich 1968, pp. 425-444.

- Theodor Eschenburg : Franz von Papen . (PDF; 902 kB) In: VJZG 1, 1953, pp. 153–169.

- Joachim Fest : Franz von Papen and the conservative collaboration . In: Ders .: The face of the Third Reich. Profile of a totalitarian rule . Munich 1963, pp. 209-224.

- Heinz Höhne : Franz von Papen . In: Wilhelm von Sternburg (Ed.): The German Chancellors. From Bismarck to Schmidt . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt 1987, pp. 325-335.

- Rudolf Morsey : Franz von Papen (1879-1969) . In the S. (Ed.): Zeitgeschichte in Lebensbildern , Vol. II, pp. 75–87.

- Rudolf Morsey: Papen, Franz von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-00201-6 , pp. 46-48 ( digitized version ).

- Daniel Schmidt: Franz von Papen (1879–1969). In: Friedrich Gerhard Hohmann (Ed.): Westfälische Lebensbilder . Münster iW, 2015, ISBN 978-3-402-15117-4 , Vol. 19, pp. 141–168 (Publications of the Historical Commission for Westphalia, New Series 16).

Monographs on special aspects

- Jürgen Arne Bach : Franz von Papen in the Weimar Republic. Activities in politics and the press 1918–1932. 2nd Edition. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-7700-0454-X .

- Ulrike Hörster-Philipps : Conservative politics in the final phase of the Weimar Republic. The Franz von Papen government . 1982.

- Franz Müller: A “right-wing Catholic” between the cross and the swastika. Franz von Papen as Hitler's special agent in Vienna 1934–1938 . 1990.

- Hans Rein: Franz von Papen in the twilight of history. His last trial . 1979.

- Thomas Trumpp : Franz von Papen. the Prussian-German dualism and the NSDAP in Prussia; a contribution to the prehistory of July 20, 1932 . Tubingen 1963.

Essays on special issues

- Larry Eugene Jones : Franz von Papen, the German Center Party, and the Failure of Catholic Conservatism in the Weimar Republic . In: Central European History , vol. 38, 2005, pp. 191-217.

- Reiner Möckelmann: The Adversary Ambassador Franz von Papen . In: Ankara waiting room. Ernst Reuter - exile and return to Berlin . Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-8305-3143-2 .

- Karl Heinz Roth : Franz von Papen and German fascism . In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft (ZfG), vol. 51 (2003), pp. 589–625.

Non-scientific literature

- HW Blood-Ryan : Franz Von Papen. His Life and Times . London 1939.

- Oswald Dutch : The Errant Diplomat. The Life of Franz Von Papen . London 1940.

- Tibor Koeves : Satan in Top Hat. The Biography of Franz von Papen . New York 1941.

- Heinrich Schnee : Franz von Papen, a picture of life . Wroclaw 1934.

- Walter Schotte : The Papen - Schleicher - Gayl government . Berlin 1933.

- Carl Severing : Pioneer of National Socialism. Franz v. Papen. A portrait sketch . 1947.

- Franz von Papen . In: Der Spiegel . No. 19 , 1969 ( online ).

- Willi Winkler : The always compliant - New documents on the dismissal of Franz von Papen . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , April 19, 2015.

Web links

- Literature by and about Franz von Papen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Franz von Papen in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Franz von Papen in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Sonja Kock, Gabriel Eikenberg: Franz von Papen. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Radio address by the Reich Chancellor on the Reichstag election on November 6, 1932 in the LeMO (DHM and HdG)

- Preussen-Chronik.de about Franz von Papen

- Reiner Zilkenat : “Lead a dictatorship on a national basis!” On June 1, 1932, Hindenburg appointed Franz von Papen as Reich Chancellor

- Heiner Wember : May 2nd, 1969 - anniversary of the death of politician Franz von Papen, WDR ZeitZeichen from May 2nd, 2014 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ St. Saul Levitt: A Letter to Von Papen. In: Yank The Army Weekly. March 23, 1945, accessed December 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture, losses - damage - reconstruction, a documentation for the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany, Vol. II: Süd, Wiesbaden 2000, p. 1083.

- ^ Rainer Orth: The official seat of the opposition? Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-50555-4 , p. 1111 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Hans Kroll: Memoirs of an Ambassador. 1967, p. 140.

- ↑ Tim Weiner : FBI. The real story of a legendary organization. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Larry Eugene Jones: Franz Von Papen, the German Center Party, and the Failure of Catholic Conservatism in the Weimar Republic. In: Central European History. Vol. 38, no. 2, 2005, pp. 191-217.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schumann , Ludwig Nestler (ed.): Weltherrschaft im Visier, documents on the European and world domination plans of German imperialism from the turn of the century to May 1945. Berlin 1975, p. 203.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schumann: World domination in sight. P. 207.

- ^ Günter Rosenfeld : Soviet Union and Germany 1922–1933. Berlin 1984, p. 450.

- ↑ Werner von Rheinbaben: Erlebte Zeitgeschichte. 1965, p. 40. At the same point, Rheinbaben mentions that Schleicher's choice of Papen only fell after Count Westarp had refused the post of chancellor.

- ↑ also on the following Karl Dietrich Bracher : The dissolution of the Weimar Republic. A study on the problem of the decline in power in a democracy. Paperback edition, Droste, Düsseldorf 1984, pp. 471–479.

- ^ Gerhard Schulz: From Brüning to Hitler. The change in the political system in Germany 1930–1933. (= Between democracy and dictatorship. Constitutional policy and imperial reform in the Weimar Republic. Vol. 3) alter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1992, pp. 887–895.

- ↑ Philipp Heyde: The end of the reparations. Germany, France and the Young Plan 1929–1932. Schöningh, Paderborn 1998, pp. 408-444.

- ↑ Reinhard Neebe: Big Industry, State and NSDAP 1930-1933. Paul Silverberg and the Reich Association of German Industry in the Crisis of the Weimar Republic (= critical studies on historical science. Volume 45). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1981, pp. 127-139; Henry A. Turner : The Big Entrepreneurs and the Rise of Hitler. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1985, pp. 316, 335 f., 357 f., 362-367.

- ↑ Erich Eyck : History of the Weimar Republic , Volume 2.

- ^ Wilfried von Bredow, Thomas Noetzel: Political judgment. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-15978-2 , p. 18.

- ^ Jones: Catholic Conservatives , p. 282.

- ^ Petzold: Verfahrnis, p. 177.

- ^ Jones: Catholic Conservatives , p. 283.

- ^ Grass: Papenkreis , p. 70.

- ^ Alfred Kube: Pour le mérite and swastika. Hermann Göring in the Third Reich. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, p. 31.

- ^ Petzold: Verfahrnis, p. 267.

- ^ Larry Eugene Jones: Franz von Papen, Catholic Conservatives, and the Third Reich , pp. 285-290 ("The League of Catholic Germans Cross and Eagle"); Herbert Gottwald: Bund Katholischer Deutscher "Kreuz und Adler" (BkD) 1933 , in: Lexicon for the history of parties , Vol. 1, Leipzig 1983, pp. 348-350.

- ↑ a b Reiner Möckelmann: Franz von Papen. Hitler's eternal vassal . Zabern-Verlag, Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-8053-5026-6 , pp. 310 .

- ^ Petzold: Verfahrnis , pp. 179 and 210.

- ↑ Ulrich von Hehl: Wilhelm Marx , 1978, p. 473; Edmund Forschbach: Edgar Jung. A Conservative Revolutionary June 30, 1934 , 1984, p. 76.

- ^ Karl Martin Grass: Edgar Jung, Papenkreis and Röhmkrise 1933–1934 , 1968 pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: Mordsache Röhm, 1984, p. 232.

- ^ Yearbook of the Academy for German Law, 1st year 1933/34. Edited by Hans Frank. (Munich, Berlin, Leipzig: Schweitzer Verlag), p. 256.

- ^ Konrad Heiden: Adolf Hitler. The age of irresponsibility. A biography. Europa-Verlag, Zurich 1938, p. 423.

- ^ Konrad Heiden: Adolf Hitler. The age of irresponsibility. A biography. Europa-Verlag, Zurich 1936, p. 447.

- ^ Papen assassination failed Chronicle of the Second World War. Edited by Hanno Ballhausen. Munich / Gütersloh 2004, p. 180.

- ↑ Marina Sorokina / Gabriel Superfin, 'Byl takoj pisatel' Ageev… 'Versija sud'by ili o pol'ze naivnogo biografizma, in: Minuvšee. Istoričeskij al'manach [Moscow / St.Petersburg], 16 (1994), pp. 269-271.

- ↑ Franz von Papen: The truth one alley. Innsbruck 1952, p. 594.

- ^ FDR's Tragic Mistake

- ↑ Joseph E. Persico: Roosevelt's Secret War. FDR and World War II Espionage. New York 2002, pp. 233-234.

- ^ Möckelmann: Franz von Papen . S. 201-246 .

- ↑ Germany, July 1941–1944 List of Key Nazis (December 10, 1942), p. 72, National Archives NARA

- ^ Möckelmann: Franz von Papen . S. 343 ff .

- ↑ Franz von Papen (1879–1969)

- ^ Drek S. Zumbro: Battle for the Ruhr. The German Army's Final Defeat in the West. 2006, p. 365.

- ↑ Note: many high-ranking detainees were released early between around 1949 and around 1952.

- ^ Möckelmann: Franz von Papen . S. 399 ff .

- ↑ Quarterly Books for Contemporary History. Volume 1 / Issue 2 1953. pp. 153–169 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b Hitler's table talks in the Führer Headquarters. Table talk on January 18, 1942.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner: Historical Variations.

- ↑ Raumer's letter to Werner von Rheinbaben dated February 9, 1963, Rheinbaben estate, BAK, file 1.

- ↑ a b Hans-Otto Meissner: Young Years in the Reich President's Palace. 1987, p. 326.

- ↑ Hans-Otto Meissner: Young Years in the Reich President's Palace. 1987, p. 81. At p. 322.

- ↑ Hans-Otto Meissner: Young Years in the Reich President's Palace. 1987, p. 326. When dancing, for example, Papen always expected that space would be made for him everywhere on the parquet.

- ↑ Hans-Otto Meissner: Young Years in the Reich President's Palace. 1987, p. 322.

- ^ Fritz Günther von Tschirschky: Memories of a high traitor. 1972, p. 135.

- ^ Fritz Günther von Tschirschky: Memories of a high traitor. 1972, p. 136. He adds that Papen knew how to “win over” friends and foes through “captivating charm”.

- ^ Kurt Petzold: Franz von Papen.

- ↑ Kurt Tucholsky: Complete Edition. Texts and letters. 1996, p. 157.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Alfred Polgar. Collected Works. Vol. 1 pattern. P. 180. It goes on to say: “He lacks nothing but the personality, the format, the skill, the cleverness and the talent to be a little Fouché, on whose mask, by the way, the narrow, nervously scented fox face of Herr von Papen a little reminiscent. ”Furthermore, Polgar Papen explains about a man who could only be successful where fraud and deceit are involved:“ In Ankara the Herrenreiter Papen failed. It seems to have been an honest, not pushed race: so Papen's chances of success were slim right from the start. "

- ↑ It should not happen to a Papen. In: Time Magazine , October 20, 1941.

- ^ Joachim Petzold: Franz von Papen. A German fate. Munich 1995.

- ^ Karl Dietrich Bracher on Franz v. Papen: "On the Failure of a Democracy" ON THE KILLER OF A DEMOCRACY . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1968, pp. 160-164 ( online ).

- ↑ Philipp Heyde: The end of the reparations. Germany, France and the Young Plan 1929–1932. Paderborn 1998, p. 429 f.

- ^ Richard W. Rolfs: The Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Life of Franz Von Papen. 1996.

- ↑ Joachim C. Fest: The face of the Third Reich. Profiles of a totalitarian rule , Piper Verlag, 9th edition, Munich 2006, p. 209 u. 221.

- ^ Golo Mann: German history of the 19th and 20th centuries , S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 2009, p. 794.

- ^ Golo Mann: German History of the 19th and 20th Centuries , S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1973, p. 784 ff.

- ^ Henry M. Adams / Robin K. Adams: Rebel Patriot. A Biography of Franz von Papen. Santa Barbara 1987.

- ^ Friedrich-Karl von Plehwe: Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher. Weimar's last chance against Hitler. 1983.

- ↑ Honorary title: Catholic nuisance . In: Der Spiegel . No. 46 , 1959 ( online ).

- ^ Petzold: Verfahrnis , p. 7 f.

- ↑ VJHZG , 63rd vol., No. 2, p. 322 f.

- ^ Müller: Rechtskatholik , pp. 19 and 375–377.

- ↑ Artist collective steals Franz von Papen's tombstone. Berliner Morgenpost from December 3, 2019.

- ↑ New campaign from the "Center for Political Beauty": Von Papen tombstone placed in front of the CDU party headquarters , rbb24.de, December 7, 2019.

- ↑ https://rp-online.de/politik/deutschland/franz-von-papen-grabplatte-vor-cdu-zentrale-aufgetaucht_aid-47678247

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Kurth Rieth |

German ambassador to Austria 1934–1938 |

Carl-Hermann Müller-Graaf |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Papen, Franz von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Papen, Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (Center Party), MdR and Chancellor of the Weimar Republic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 29, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Werl |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 2nd 1969 |

| Place of death | Obersasbach |