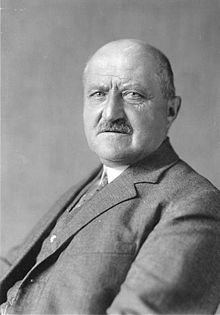

Georg Michaelis

Georg Michaelis (born September 8, 1857 in Haynau , Silesia ; † July 24, 1936 in Bad Saarow , Mark Brandenburg ) was a German lawyer and politician . From July 14 to November 1, 1917, he was Reich Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister for three and a half months .

Michaelis had previously been Undersecretary of State and was considered rather inexperienced. The politically conservative official refused to convert the constitutional system in Germany into a parliamentary form of government. During his term of office, the debate and adoption of the peace resolution of the majority parliamentary groups in the Reichstag, who wanted to end the First World War with a mutual agreement, fell. Michaelis failed after the summer of 1917 and served in 1918/1919 as Upper President of the Province of Pomerania.

Life

Georg Michaelis came from a family of lawyers on his father's side, which also included Friedrich Michaelis (1726–1781), the Kurmark provincial minister under Frederick the Great. His father was last judge of appeals in Frankfurt (Oder) , he died of cholera in 1866 . His mother was born von Tschirschky , daughter of the officer and revival preacher Carl von Tschirschky-Bögendorff (1802-1833). Among Georg Michaelis' six siblings were Johann Michaelis (1855-1910), who became a Prussian major general, and Walter Michaelis , who became pastor and chairman of the Gnadau community association .

Georg Michaelis married Margarete Schmidt (1869–1958), daughter of a Guben factory owner and manor. The two had five daughters and two sons. The son Wilhelm Michaelis (1900-1994) was senior city director of Recklinghausen. The daughter Eva Michaelis (* 1904) married the Protestant theologian Hermann Schlingensiepen .

education

After graduating from high school in 1876, Georg Michaelis studied law at the Silesian Friedrich-Wilhelms University in Breslau and the University of Leipzig . In 1877 he became active in the Corps Plavia . He moved to the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg and also joined the Corps Guestphalia Würzburg . A Konaktiver was Moritz Fünfstück . Without proof of the dissertation he was in 1884 at the Georg-August University of Göttingen to Dr. iur. PhD . 1885-1889 he taught at the Dokkyō University in Tokyo.

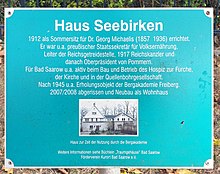

Advancement in the administration of Prussia

After his return to Germany Michaelis went into the Prussian civil service. Here he was first a public prosecutor, but then went into internal administration. He worked for the government in Trier , the government in Arnsberg and the government in Liegnitz . From 1902 to 1909 he was Senior President in the Upper Presidium of the Province of Silesia . At that time he was socially active with the deaconess Eva von Thiele-Winckler , for example in founding a welfare home for released female prisoners in Langenau (Czernica) in Lower Silesia. In 1909 he became Undersecretary of State in the Prussian Ministry of Finance. In 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, he took over the management of the Reichs Grain Office in a secondary position . In 1917 he rose to the position of Prussian State Commissioner for People's Nutrition. Michaelis was involved in the management level of the German Christian Student Association . He had a training center built for students in his summer residence in Bad Saarow . The temporary structures were a wooden meeting house for 800 listeners and a former prisoner-of-war barracks. In 1921 the permanent house Hospiz zur Furche was completed. To ensure the supply, the Vorwerk of the Saarow estate, the Marienhöhe farm, was acquired . However, it could not be operated economically and was sold to Erhard Bartsch in 1928 . He switched the farm to biodynamic farming ( Demeter ).

Imperial Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister

Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg had increasingly maneuvered himself between the fronts in the course of the First World War. The Supreme Army Command considered him too weak in relation to the Reichstag; Other circles around the emperor and the right wing in the Reichstag complained to him that he had moved too far to the left. In the Reichstag, on the other hand, the majority considered him too weak against the OHL. He also approached the question of internal reforms too hesitantly.

On July 13, 1917, Bethman Hollweg was released. Because of the suddenness, the majority in the Reichstag was unable to agree on a successor and to force his appointment. Such a personality was also not available. The next day, on July 14, the Emperor appointed Michaelis Chancellor. The head of the press office of the Reich Office of the Interior , Magnus von Braun , thought Michaelis was a suitable candidate and then convinced influential politicians and the military. Finally, Vice Chancellor Helfferich recommended the candidate to the Kaiser.

Michaelis was inexperienced in the big questions of domestic and foreign policy. In an interview with the party leaders, soon after taking office, he made the following statement: "Up to now, I have run up to the side of the big politics as an ordinary contemporary and just tried to keep myself up to date like a newspaper reader." This was meant as an understatement, was meant by but immediately valued by the opponents as an admission of inexperience. In fact, he did show skill in talking to the party leaders.

He could probably be presented to foreign countries and the parties of the Reichstag as a fresh face. In terms of constitutional politics, however, Michaelis was close to his predecessor Bethman Hollweg: Michaelis rejected a parliamentary form of government and wanted to remain independent of a majority in the Reichstag in foreign policy. He appointed a number of parliamentarians to the Reich leadership and the Prussian cabinet, but mostly only rights and subordinate positions. His task was extremely difficult, since he had to please both the right and the left, and had to work with both the military and parliament.

Bethmann Hollweg's fall was only apparently a victory for parliamentarism, said Huber. Rather, it was a tactical success of the OHL:

- “She had used parliamentary forces to overthrow the previous Chancellor, but covered them up in the decision on the Reich leadership. Strategically, however, the crisis policy of the Supreme Army Command ended in failure. Because the disabled majority in the Reichstag did everything to compensate for the exposure [...] with an early counter-attack. She therefore met the Chancellor, who was appointed without her intervention, with such suspicion from the start that it was hopeless for him to hold his own for longer than just a transitional period. "

One of the big questions of his chancellorship was the peace resolution of the parties of the majority, the intergroup committee consisting of the SPD, left-liberals and the center. Michaelis tried not to reject the resolution outright, but wanted to carefully distance himself from it. Outside of parliament, the German Fatherland Party was formed as a sharp right-wing opposition to a mutual agreement or waiver. On the left, the USPD was suspected of being involved in the sailors' uprisings of the summer of 1917 . The majority SPD under Friedrich Ebert stood by the USPD out of concern that MPs would be harassed. A vote of no confidence by the USPD against Michaelis on October 9 was followed by the majority SPD, but not by the center and the left-wing liberals.

Shortly afterwards Michaelis was on a trip to the Balkans until October 21st. The parties used the time after the unsuccessful overthrow of the Chancellor to secure a successor in good time this time. On October 23, the parties of the Intergroup Committee and representatives of the National Liberals met about this. They unsuccessfully discussed a successor and agreed on a minimum political program which, among other things, provided for increased peace efforts and a new right to vote in Prussia . They recommended that the emperor change the Chancellor quickly after a meeting with the Reichstag.

The emperor refused to parliamentarise the selection of the chancellor, but on October 26th Michaelis asked him to be dismissed. Michaelis, however, wanted to remain Prussian Prime Minister, while the Bavarian Prime Minister Georg von Hertling was to become the new Chancellor. The emperor agreed with the idea: in this way one could make the thrust of parliament appear less powerful. Chancellor Hertling would be given more representative tasks, while Michaelis, as Prussian Prime Minister, steers imperial politics through the Bundesrat and with the help of the OHL.

Hertling negotiated from October 27 to 30 in Berlin with Vice Chancellor Helfferich and the party leaders. The conservative center politician agreed to the (vaguely worded) minimum program and to appoint some representatives of the majority parties to the cabinets. In agreement with the majority parties, however, he insisted on becoming both Chancellor and Prime Minister. The emperor's advisors couldn't help but recommend Hertling's appointment to the emperor. On November 1st, the emperor dismissed Michaelis and appointed Hertling as his successor in both offices.

President of the Province of Pomerania

On April 1, 1918 Michaelis became President of the Province of Pomerania . As an administrative specialist, especially a specialist in nutritional issues, he was in the right place. After the November Revolution, he initially remained senior president and also instructed the subordinate district presidents and district administrators to remain in their offices in principle.

He worked for a centralization of welfare at the provincial level. In the autumn of 1918 he set up the main office for war welfare at the high presidium. In December 1918, he converted this into the legal form of a registered association, initially becoming its chairman until he appointed the Pomeranian governor Johannes Sarnow as the new chairman in March 1919 . From the beginning of 1919 Michaelis got involved in the reception of German-Baltic refugees (Baltenhülfe).

Michaelis supported the German National People's Party in the election to the German National Assembly in January 1919 . The opposition to the parties of the ruling Weimar coalition became too great, so that Michaelis was retired on April 1, 1919. His successor as chief president was the liberal Julius Lippmann .

Last years

Michaelis was involved in the general synod and church council of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union . He saw East Asia again in 1922 when he made a trip to Beijing to attend the Conference of the World Student Christian Federation .

In 1926 Michaelis had to justify his behavior as Reich Chancellor to an investigative committee of the Reichstag. He was scolded for preventing the peace initiative:

“This little man might have saved the world a year of war, saved millions of lives, and brought the German people a peace of equilibrium and understanding. He didn't do it. Right from the start he crossed the path that could have led to this goal of happiness. "

Fonts (selection)

- For the state and the people. A life story. Furche, Berlin 1922. ( excerpts published in 2010 )

- World travel thoughts. Furche, Berlin 1923.

- Bert Becker (ed.): Georg Michaelis: A Prussian lawyer in Japan during the Meiji period. Letters, diary notes, documents 1885–1889. Iudicium, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-89129-650-9 .

literature

- Bert Becker: Georg Michaelis: Prussian official, Reich Chancellor, Christian reformer 1857-1936. A biography. Schöningh, Paderborn 2007. ISBN 978-3-506-76381-5 .

- Bert Becker: Michaelis, Georg (1857-1936) . In: Dirk Alvermann , Nils Jörn (Hrsg.): Biographisches Lexikon für Pommern . Volume 2 (= publications of the Historical Commission for Pomerania. Series V, Volume 48.2). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne Weimar Vienna 2015, pp. 175–179. ISBN 978-3-412-22541-4

- Rudolf Morsey : Michaelis, Georg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-428-00198-2 , pp. 432-434 ( digitized version ).

- Christoph Regulski : The Chancellorship of Georg Michaelis in 1917. Germany's development to a parliamentary-democratic monarchy in the First World War. Tectum, Marburg 2003. ISBN 3-8288-8446-6 .

- Robert Volz: Reich manual of the German society . The handbook of personalities in words and pictures. Volume 2: L-Z. Deutscher Wirtschaftsverlag, Berlin 1931, pp. 1248–1249.

Web links

- Literature by and about Georg Michaelis in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Georg Michaelis in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Georg Michaelis in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Search for "Georg Michaelis" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Sonja Kock, Kai-Britt Albrecht: Georg Michaelis. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Kösener Corpslisten 1930, 95/21; 139/30

- ↑ Georg Michaelis with Leibfüchsen (VfcG)

- ↑ For the state and the people. A life story. Berlin, Furche 1922, p. 245

- ↑ today's address: An den Rehwiesen 25, Bad Saarow

- ↑ today: Hof Marienhöhe

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, pp. 313-315.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, p. 316.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, pp. 314-316.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, p. 315/316.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, pp. 382-384.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, pp. 386/387.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1978, p. 392, p. 395.

- ↑ Quoted from: Vorwärts (Germany) . Evening edition of December 14, 1926, p. 1 (there, pp. 1–2, detailed report)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Michaelis, Georg |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German lawyer and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 8, 1857 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Haynau , Lower Silesia |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 24, 1936 |

| Place of death | Bad Saarow , Brandenburg |