Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( Russian Альфред Вольдемарович Розенберг , Alfred Woldemarowitsch Rosenberg ; * December 31, 1892 July / January 12, 1893 greg. In Reval ; † October 16, 1946 in Nuremberg ) was a politician and leading socialist at the time of the Weimar Republic and National Socialism Ideologist of the NSDAP . As a student, he witnessed the revolution in Moscow in 1917 . Like the Russian right-wing extremists , he interpreted this as the result of a Jewish- Masonic world conspiracy . With this idea he later significantly shaped the ideology of the NSDAP. From 1920, Rosenberg contributed significantly to the intensification of anti-Semitism in Germany with numerous writings on racial ideology . During the Second World War , he and his task force Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) undertook raids all over Europe, in particular for the theft of cultural goods . As head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO), as part of his Ostpolitik , he pursued the project of Germanizing the occupied Eastern Territories with the simultaneous systematic extermination of the Jews . Rosenberg was indicted in the Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals, found guilty on all four counts, sentenced to death and executed.

Origin and family

Youthful coinage

For a long time it was puzzled whether the ardent anti-Semite Rosenberg might have Jewish ancestors himself. The interest in this question arose for the first time in the month of the publication of his anti-Semitic work The Myth of the 20th Century and his election to the Reichstag in October 1930. At the time, the public spoke of the fact that “not a drop of German blood ” was flowing in his veins and among his ancestors there were only “Latvians, Jews, Mongols and French”. This statement is said to have been made by the journalist Franz Szell and, on September 15, 1937, by the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano . However, so far no Jewish family roots have been proven. Precise information is now available about Alfred Rosenberg's grandparents: The paternal grandfather, the master shoemaker Martin Rosenberg (1820–1896), probably of Latvian origin, married Julie Stramm from Jörden / Estonia in 1856 in the German St. Nicholas' community in Reval (* 1835). The son Woldemar Rosenberg (1862–1904) was their third child. - Alfred Rosenberg's maternal grandfather was the railway official Friedrich August Siré (* 1843 in St. Petersburg , there belongs to the Evangelical Lutheran St. Catherine's Congregation); He married Louise Rosalie Fabricius (* 1842 in Leal / Estonia, her father was the white tanner Johann Carl Fabricius) in the Latvian Jesus Church in St. Petersburg . Her daughter Elfriede Caroline Louise Siré (1868-1893) was born in St. Petersburg and was confirmed in Reval in 1885. Woldemar Rosenberg and Elfriede Siré married in 1886 in the St. Petersburg Evangelical Lutheran St. Petri Church .

The first years of Alfred Rosenberg's life , who grew up in a large Baltic German family in the house at Poststrasse 9 in Reval , which then belonged to Russia , were shaped by several deaths. Just two months after his birth, his mother Elfriede Caroline Siré died of tuberculosis . When Rosenberg was eleven years old, his father Woldemar Wilhelm Rosenberg, a businessman with roots in Livonia , died in 1904 after a long illness ; Then his grandmother in 1905. Two of his father's sisters, Cäcilie Rosalie (born 1860) and Lydia Henriette (born 1864), whom he later always remembered with gratitude, became his foster mothers.

He met Hilda Leesmann, whom he married in 1915. Her family was considered to be extremely cultured, educated and had numerous relationships with Saint Petersburg society. It was primarily through this connection, as he later indicated in his Nazi memoir, that Rosenberg began to read popular literature, especially philosophical books from German idealism , such as Herder and Fichte , the Weimar Classic ( Goethe ), novels ( Charles Dickens ), hero myths ( Thomas Carlyle ) and Christian social literature ( Ralph Waldo Emerson ) as well as important classics of 19th century Russian literature. Later, between 1909 and 1912, writings on the philosophy of nature ( Arthur Schopenhauer ) and philosophy of life by Nietzsche as well as books by Chamberlain that were transfigured by racial ideology and Christianity were added, whereby Rosenberg was particularly impressed by Chamberlain's writings on Goethe and Kant , as Alfred Baeumler added in an introduction Rosenberg's early notes during the war. These writings are said to have made more of an impression on Rosenberg at that time than Chamberlain's then popular book Foundations of the Nineteenth Century . And in 1946 Rosenberg regretted that he had received “no humanistic training” during his youth .

While he was still at school at the Petri-Oberrealschule, which he attended until June 1910, Rosenberg discovered his interest in prehistory , especially archeology , and in the migration of peoples . The interest in this arose from the suggestions of his geography teacher Spreekelsen, who was mainly based on the history books of the historian Dmitrij Iwanowitsch Ilowaiski (1832-1920), popular and mythologized in pre-revolutionary Russia . With Spreekelsen, Rosenberg had also successfully participated in an excavation. These events coincide with a time when books by the prehistory writer Gustaf Kossinna were becoming popular. In these early years, the foundation stone was laid at Rosenberg, which later led him to ideologically orient and popularize “research on prehistory” in Germany. About Rosenberg's later " Office Rosenberg ", the affiliated " Reich Association for German Prehistory " with the prehistorian Hans Reinerth , the "Nordic Association" with Walter Darré and Heinrich Himmler (who founded the " Research Association of German Ahnenerbe "), formed in the following Years ago, a sphere of activity emerged that later massively determined the content of the politicized lesson plans in German schools.

Revolutionary art

Shaped by personal and social crisis experiences as well as Christian and ethnic ideas that were popular around the turn of the century, Rosenberg began studying architecture at the Polytechnic in Riga in autumn 1910 , where the well-known Wagner admirer Carl Friedrich Glasenapp was also working at the same time . In the same year Rosenberg became a committed member of the Corps Rubonia, founded in 1875 . During his student days, like Adolf Hitler at the same time, he got to know the musical dramas of the composer and anti-Semitic political writer Richard Wagner , who was also admired by Chamberlain , for whose operas Rosenberg visited the theater several times. Rosenberg was particularly fond of Wagner's Mastersingers and Tristan and Isolde as well as Wolfram von Eschenbach's verse novel Parzival , the literary basis for Wagner's Parsifal .

After the beginning of the First World War , the Riga Polytechnic was evacuated to Moscow with all its professors in the summer of 1915 , and on September 3, 1917, Riga was captured by German troops. In Moscow, where Rosenberg witnessed the end of the tsarist rule, the October Revolution and the tyranny of the Bolsheviks , whom he despised , he completed his studies in spring 1918 with a thesis on the architecture of a crematorium suitable for Russian standards .

Rosenberg does not seem to have been particularly interested in the outcome of the war; during the revolution he dealt with German and Indian philosophy and art. As early as January 1917, Rosenberg had begun to write down individual thoughts in the form of aphorisms and short essays in oilcloth notebooks. These transcripts, made in Moscow, Reval and later also in Munich, which he had published in 1943, end in November 1919. His early notes provide evidence of his existential search for an identity and begin programmatically with the remark: “One can often observe that a person who is revolutionary in one art traditionally thinks about another. ”Accordingly, Rosenberg was not completely alien to the February Revolution and once described it as an event of outstanding magnitude. He recorded his thoughts on the February Revolution in Russian. 15 months later, according to Laqueur , he had developed into a fanatical anti-Semite. Behind all attempts at political and social destructiveness, he always saw “the Jew”. He said that while traveling around Russia he had seen Jewish students agitating in spa facilities, military hospitals and elsewhere with Pravda in hand, and presented this as evidence that almost all left-wing socialists were Jews. When Rosenberg returned to his hometown in the spring of 1918, German troops were still stationed there fighting against units of the Red Army . The political situation was still tense. Rosenberg was certain: “But what was missing was a leader , a battle cry for the future. Nobody wanted to fight for the return of those who had fallen ”, as he later wrote in his diary. Trained by the Latvian painter Wilhelm Purwit (Lat. Vilhelms Purvītis), from whom he had already received private lessons during his school days, as well as through his studies, he initially began to work penniless as a drawing teacher at the Gustav-Adolf-Gymnasium. At the same time he wrote his first anti-Semitic essays with the titles A Serious Question (around May 1918), by which he understood the Jewish question , then his reform sketches On Religious Education (June 1918) and finally the longest of his entire early writings with the title Der Jude ( July 1918). Already here he used a racist terminology, whereby he justified his anti-Semitism in particular with an appeal to Fichte and Wagner, was already committed to a dualism between " Jews and Aryans " and demanded that "the Jews" - while respecting " human rights " - the " civil rights " would have to be withdrawn. A month earlier, in May 1918, he had committed himself to a firm associative connection between “ socialism ”, “national chaos” and “Jews” in his early writings and - like Richard Wagner once too - claimed that Jewish people were part of an artistic production , by which Rosenberg also understood the creation of a "state structure", were not capable. The idea had evidently also grown with a view to the Bolsheviks, who, in his opinion, were unable to stabilize the political order after the revolution.

The gesture of genius , which was a widespread social symptom of decadence at the turn of the century , was clearly illustrated by Rosenberg together with his enemy image “Jews” - and he never abandoned this gesture in accordance with his unfolding racial ideology. On November 30, 1918, he gave a lecture on "the Jewish question" in a large hall he had rented in the House of the Blackheads , and on the same evening he left his hometown to travel to Berlin. Only a few days later he intended to leave Berlin again. At first he thought of London because he believed that only Great Britain would be able to fight Bolshevism - by which he always understood Judaism . His application for a visa was turned down by London because the British government feared Russian infiltration. Finally he traveled to Munich, at that time a contact point for numerous immigrating Baltic Germans . With his replacement Russian passport, he introduced himself to Hetman Pawlo Skoropadskyj , the Ukrainian chairman of an emigre association, and he quickly succeeded in making contact with Belarusian emigrant circles. In Munich he initially maintained contacts with the Baltic painters Otto von Kursell and Ernst Friedrich Tode , and only a short time after his arrival he attended a demonstration of revolutionary artists in the Deutsches Theater . Rosenberg was of the opinion that these people were “artistically stripped down” who - like himself - “wanted to gain meaning with the help of a new wave”.

Weimar Republic

Political writer

In the spring of 1919 he gave his first political speech in Munich, in which he formulated his rejection of the revolution in conscious reference to a speech by the far-right Duma deputy Markov II. Despite important contact persons, the situation was not easy for Rosenberg at first. He was almost penniless, spoke poor German and was a Russian citizen until February 1923; and after the suppression of the Soviet republic Rosenberg could only stay in Munich through the intercession of his publisher, the German national Thule member Julius Friedrich Lehmann.

With the beginning of the Weimar Republic , Rosenberg published his first writings such as The Trace of the Jew in the Changing Times (1919), The Crime of Freemasonry. Judaism, Jesuitism, German Christianity (1921), the stock exchange and Marxism or the master and the servant (1922) or the text Anti-subversive Zionism. Their summary is: "Zionism is [...] a means for ambitious speculators to create a new staging area for world growth ."

He spread a theory of the " Jewish - Masonic world conspiracy " (židomasonstvo), which had been adopted by the Russian extreme right , and which aimed to "undermine the existence of other peoples" . To this end, the Freemasons brought about the World War and the Jews the Russian Revolution . Therefore, capitalism and communism are only apparent opposites, in truth it is a matter of one and the same pincer movement with which “ international Jewry ” strives for world domination ( High finance as the mistress of the workers' movement in all countries , 1924). This idea goes back largely to an anti-Semitic work by Dostoyevsky , which Rosenberg repeatedly cited. The emergence of these thoughts must, however, also be seen in connection with the crisis-ridden, excited climate in Germany in the early 1920s . Here they found numerous followers and contributed to the image of a " Jewish-Bolshevik world conspiracy" that was to form the core of Hitler's thought, propaganda and politics. Rosenberg's biographer Ernst Piper even wrote that Rosenberg had made a decisive contribution to conveying to Hitler the image of the supposedly Jewish character of the Russian Revolution.

In 1923 Rosenberg published a commentary on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion , an anti-Semitic inflammatory pamphlet that he had campaigned for since his arrival in Germany and that was quoted several times in Mein Kampf two years later . It says:

“A new era begins today in the midst of the collapse of a whole world. [...] One of the signs of this coming struggle for a new world design is the knowledge of the nature of the demon of our present day decline. "

The influence of ideas of the Russian right-wing extremists on Rosenberg was not limited to his time in Russia, but he carefully studied the emigrant newspapers of the Russian right-wing extremists and used them extensively for his own work. What he had to say about Jews and Jewish culture, according to Laqueur, can be read almost word for word in the writings published by Fyodor Winberg in 1919, and Pest in Russland , published in 1922, can be described and educated as Rosenberg's variant of Fyodor Winberg's Krestnyj Put also the climax of the appropriation of positions by the emigrants.

Rosenberg was a member of the Scheubner judge launched Economic Construction Association , which wanted to restore the pre-revolutionary order in Europe, and drove like other members of this organization for German-Russian cooperation against the world Jewry propaganda. Accordingly, his image of Russia in the first post-war years was by no means, as in his later writings, clearly Russophobic, rather he established positive relationships between the peoples and their culturally important artists and writers.

His point of view also led him to see the distancing of National Socialism from national Bolshevism and other forces that were striving for rapprochement with the Soviet Union as a main task. Like other construction members, he interpreted the extermination policy carried out by the Bolsheviks as a targeted extermination of the Russian national intelligentsia and warned that the fate of Russia threatened other countries as well. Although he condemned the actions of the Bolsheviks, he also noted its "expediency".

In 1921 he and Dietrich Eckart switched to the Völkischer Beobachter , whose editor-in-chief he took over from Eckart in February 1923; this shows the strong position that Rosenberg had built for himself with his conspiracy theories within the National Socialist movement. From 1937 he was finally editor of the paper.

Prohibition phase of the NSDAP

Rosenberg took part in the " March on the Feldherrnhalle " in 1923, but, unlike other participants in the putsch, was not charged. While Hitler was serving his sentence, he entrusted Rosenberg with the leadership of the now banned NSDAP, a task which Rosenberg was hardly up to. Under the pseudonym Rolf Eidhalt (an anagram based on Adolf Hitler) he founded the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft (GVG) in January 1924 , but he was unable to prevent the National Socialist movement from splintering. Hermann Esser and Julius Streicher soon pushed him out of the leadership of GVG .

As head of the anti-Semitic monthly or quarterly magazine Der Weltkampf , which he published from 1924 , Rosenberg worked closely with Gregor Schwartz-Bostunitsch .

After Rosenberg's first marriage was divorced in 1923, he married a second time in 1925, and his marriage to Hedwig Kramer lasted until his death. In 1930 the daughter Irene was born and a son died shortly after birth.

Combat League for German Culture

In 1927, Rosenberg was commissioned by Hitler to found a National Socialist cultural association. Although originally intended as a cultural association of the party, the association did not appear in public until 1929 as an allegedly non-partisan " Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur " . Here various manifestations of classical modernism such as the architecture of the Bauhaus , expressionism and abstraction in painting or twelve-tone music were defamed and fought across the board as "cultural Bolshevism" .

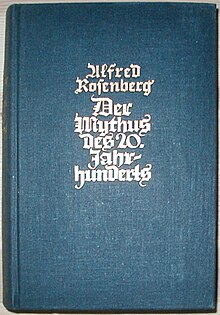

"The Myth of the 20th Century"

The book The Myth of the Twentieth Century , published in 1930, was intended as a sequel to Houston Stewart Chamberlain 's The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century . According to Rosenberg, a new “religion of the blood” must replace Christianity permeated by “Jewish influences” by replacing it with a new “ metaphysics ” of “race” and the “collective will” inherent in it.

“Race” envisioned Rosenberg as an independent organism with a collective soul, the “race soul”; he wanted everything that was individual to be suppressed. According to Rosenberg, the only race that is able to produce cultural achievements is the " Aryan race". In contrast to the Jewish religion, which Rosenberg viewed as devilish, the "Aryans" had something divine inherent in them. In Rosenberg's book, Jesus Christ became a transfigured "embodiment of the Nordic racial soul". Thus, in his opinion, Jesus could not have been a Jew. Marriage and sexual intercourse between "Aryans" and Jews are also to be placed under the death penalty.

Following the natural philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer , Rosenberg saw “ will ” not subordinate to any morality ; if a strong leader gave appropriate orders, they could be carried out. In doing so, he paved the way for the National Socialist worldview and action in which other peoples were to be suppressed and a "pure" race should be bred.

Rosenberg's racial doctrine, which he outlined against the background of his criticism of Christianity and the church, provoked numerous critical reactions. While the Protestant theologian Walter Künneth wrote an extensive refutation on behalf of the church, the Protestant Jena theology professor Walter Grundmann oriented himself on Rosenberg's demand for a “Germanization” of Christianity and founded the institute to research and eliminate the Jewish influence on German church life .

At the end of 1934, Clemens August Graf von Galen , the Catholic bishop of Münster, had the anonymous text Studies on the Myth of the 20th Century published in his diocese as an official supplement to the church gazette of his diocese. In this, among others, the Bonn church historian Wilhelm Neuss turned against Alfred Rosenberg's racial ideology, which was laid down in the myth of the 20th century . After the Archbishop of Cologne, Karl Joseph Cardinal Schulte , had withdrawn his approval for the study to be published as official publication two days before going to press, von Galen had decided to write a foreword to the book in which he was named. In his pastoral letter for Easter 1935, he dealt with Rosenberg's theses in a more acute tone. There he calls "idolatry, ... idolatry, ... relapse into the night of paganism" if the nation is viewed as the origin and ultimate goal.

Member of the Reichstag

In 1930 he entered the Reichstag as a member of the NSDAP for Darmstadt , where he was primarily involved in the Foreign Affairs Committee.

time of the nationalsocialism

Foreign Policy Office

In 1933, Rosenberg was appointed head of the NSDAP's Foreign Policy Office (APA). At the same time, Hitler made Joachim von Ribbentrop his foreign policy advisor, who now rivaled the Foreign Office , Hermann Göring and Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht for a say and influence in foreign policy. In this Nazi-typical dispute over competencies, Rosenberg initially played a role neither in the conception nor in the practical implementation of Nazi foreign policy. Accordingly, Hitler was dissatisfied. On July 28, 1933 Joseph Goebbels noted: “He [Note: Hitler] speaks sharply against Rosenberg. Because he does everything and nothing. VB is lousy. He sits in his 'foreign policy office', where he only makes botch. "

In October 1935 Rosenberg wrote an activity report of his APA, from which it can be seen that he set the focus of foreign policy activities on the Nordic Society , with which he pursued political goals with an internationalist orientation. At the same time, he put the focus of his APA on the dissemination of his racial ideological ways of thinking in the National Socialist society, which he also located beyond the German borders in accordance with his idea of Germanization :

“In terms of trade policy , in my opinion, far more sins of omission have been committed and so the APA has deliberately limited itself to its cultural-political tasks. For this purpose, the Nordic Society expanded, what used to be a small society has become a crucial intermediary for all German-Scandinavian relations in these 2 years of support from the APA . Its director (Lohse) is determined by the APA, the counting houses in all districts are led by the respective Gauleiter. Corresponding agreements have been made with economic groups and other organizations and branches of the party that have relations with Scandinavia, so that almost all traffic between Germany and Scandinavia is now handled by Nordic society. "

However, the APA demonstrated its ability to act in 1936 when it was able to submit a report on the foreign policy impact of the 1936 Winter Olympics in March 1936 . Though the report contained only twenty states, it was honest and not all pleasing to the Propaganda Department . However, it served to make the 1936 Summer Olympics an even greater success.

Ideological representative of Hitler

In June 1933, Hitler appointed Rosenberg, along with 16 other NSDAP functionaries, as Reichsleiter - a title that raised him to the Nazi leadership elite and to the same rank as ministers. In January 1934, at the suggestion of Robert Ley by Hitler, he was appointed “the Führer’s representative for the supervision of the entire intellectual and ideological training and education of the NSDAP”. In this position he built a first ideological political institution, which is referred to in the literature as " Rosenberg Office ". According to the thesis formulated by Reinhard Bollmus at the end of the 1960s, but which is controversial in more recent Rosenberg research, Rosenberg's influence remained small. As an example, Bollmus used Rosenberg's idea of a National Socialist university, the High School of the NSDAP , which was intended as a center for National Socialist ideological and educational research and was to be built by Hermann Giesler . This idea was no longer implemented after the beginning of the war. More recent research, which primarily focuses on Rosenberg's Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories or his operational staff Reichsleiter Rosenberg , has come to different results.

As important for the ideological training and education in the Nazi state today next to Rosenberg "Rosenberg Office" especially the existing schools and universities, then apply Baldur von Schirach and his Hitler Youth , Robert Ley as head of the German Labor Front and the cultural work " force by Joy ”and last but not least Joseph Goebbels as Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Against this background, Bollmus once explained that the "frustrated Rosenberg" concentrated on organizing theater-goers and went over to blackening his competitors in a "childish manner": on October 23, 1939, for example, he complained to Göring in such detail How inconsequential about a stylistically unsuccessful Goebbels speech: “Also the reference to the fact that the ravages of time would not allow grass to grow on a wound is not meant in this context as an irony on one language form of Churchill, but only another flowery form Expression of the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, which is worse than the catheter blossoms of absent-minded German professors that have been laughed at for years. "

In 1937 Rosenberg was awarded the German National Prize for Art and Science together with Ferdinand Sauerbruch and August Bier .

Operations staff Reichsleiter Rosenberg

Rosenberg played an important political role especially during the Second World War with his Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), and from 1941 onwards with the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO), which was under his leadership. With his ERR he was already responsible for the looting of Jewish archives and libraries for the “ Institute for Research on the Jewish Question ” from 1939 . From October 1940 he officially headed his task force. Hitler had authorized Rosenberg by order of the Fuehrer to confiscate extensive art treasures in the occupied territories. Large amounts of looted property were transported to Germany in railroad cars.

Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories

With the Fuehrer's decree of April 20, 1941, Rosenberg was appointed representative for the central processing of questions relating to Eastern Europe . In this function, he represented a hunger strategy in the run-up to the Barbarossa company in 1941 , which took into account the starvation of millions of civilians in the Soviet Union in order to feed the Wehrmacht out of the country and gain food for the German Reich. In a speech to representatives of the Wehrmacht and the party on June 20, 1941, two days before the start of the German-Soviet War , he named the most important war goal: “In these years, German people's nutrition is undoubtedly at the forefront of German demands in the East . [...] We do not see the obligation to feed the Russian people from these surplus areas. "

Four weeks after the attack on the Soviet Union , Rosenberg was appointed Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Baltic States, Belarus and Ukraine) on July 17, 1941 . The East Ministry was the central administrative authority for the occupied eastern territories in the Reichskommissariat Ostland and Reichskommissariat Ukraine . The Reich Commissioners there, Hinrich Lohse and Erich Koch, were directly subordinate to the RMfdbO.

In his position as "Ostminister" Rosenberg was not only jointly responsible for the ghettoization of Jews, but also for their systematic murder . At the Wannsee Conference , the RMfdbO was the only Nazi authority represented by two representatives from Rosenberg: with State Secretary Alfred Meyer and the head of the RMfdbO's Political Department, Georg Leibbrandt .

In 1943 he received from Hitler an endowment of 250,000 Reichsmarks .

Loss of power

During the Battle of Berlin , Rosenberg was initially still in Berlin. Immediately after Hitler's last birthday, on April 20, 1945, the evacuation measures prepared by the Reich government, Reich ministries and the security apparatus were carried out. The Reich Chancellery informed Rosenberg by telephone that all the ministers should gather in Eutin and announced the upcoming departure date. Alfred Rosenberg was brought to Eutin with his wife and child and then went on to Flensburg - Mürwik , where the last imperial government under Karl Dönitz settled in the Mürwik special area at the beginning of May . Doenitz informed Rosenberg in writing on May 6th: “Taking into account the current situation, I have decided to forego your further cooperation as Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories and a member of the Reich Government. Thank you for the service you have rendered to the Reich. ”Dönitz also recommended Rosenberg to surrender to the British armed forces . After the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on 7/8 May 1945 the special area Mürwik continued to exist for over two weeks. Alfred Rosenberg was still earlier, on 18 May 1945 by the Allies in the Navy hospital Flensburg-Mürwik prisoner taken, where he a severe bruise in the ankle was staying due to his left leg.

After the end of the war

Nuremberg Trial

One day after his arrest in Mürwik, Alfred Rosenberg was brought to Kiel and from there transported by plane to Luxembourg. There in Bad Mondorf he was interned with other major war criminals in the Palace Hotel , where he remained until he was transferred to Nuremberg in August 1945. The Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals began for the defendants on November 21, 1945. Rosenberg was charged with conspiracy , crimes against peace, planning, opening and waging war of aggression , war crimes and crimes against humanity . He was found guilty and sentenced to death. With regard to the conspiracy, the verdict was based on Rosenberg's function as a "recognized party philosopher" and, with regard to the crimes against peace, on Rosenberg's activity as head of the foreign affairs office. He was particularly responsible for the attacks on Denmark and Norway. With regard to the crimes against humanity, the court referred to Rosenberg's function in the Reichsleiter staff and in the East Ministry. In addition, he was shown complicity in the procurement of forced laborers .

Rosenberg asked his defense attorney to get him the diaries, which he knew were at least partially in the hands of the Americans. MIT then claimed that they were "undetectable". Robert Kempner , the United States' assistant chief prosecutor, did not hand them over. Rosenberg never made an admission of guilt, but instead tried, like most of the other co-defendants, to shift the blame onto the trio of Adolf Hitler , Heinrich Himmler and Martin Bormann, who had already died , and to pull themselves out of responsibility. Rosenberg remained arrested until the end of his own Nazi racial ideology. While still in prison he wrote:

“National Socialism was a European answer to a century's question. It was the noblest idea for which a German could use the strength given to him. He was a real social worldview and an ideal of blood-borne cultural cleanliness. "

Alfred Rosenberg was sentenced to death on October 1, 1946, and executed with nine other convicts on October 16 in the early morning hours by hanging in the Nuremberg judicial prison. The body was cremated a day later in the municipal crematorium in Munich's Ostfriedhof and the ashes were scattered in the Wenzbach , a tributary of the Isar.

Diaries

In 2013, US authorities announced that Rosenberg's diaries had resurfaced with 425 pages. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) officials confiscated them in northern New York. The German lawyer Robert Kempner , who was deputy to US chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson during the Nuremberg trial , had apparently taken it into his possession after the trial and kept it after his return to the United States. They are said to concern the years 1934 to 1944 and were handed over to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in June 2013 , which wants to evaluate the records scientifically. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has been putting handwritten pages and transcripts online since late 2013 . In 2018, the diaries for the years between 1934 and 1944 finally appeared as an annotated book edition by the historians Jürgen Matthäus and Frank Bajohr . Previously only a partial edition from the years 1934/35 and 1939/40 was known.

Impact history

For a long time Rosenberg's picture was subject to great fluctuations. Among his contemporaries and during the immediate post-war period , the author of the myth of the 20th century was regarded as a demonic master thinker, as a murderously cool intellectual of the NSDAP and its chief ideologist. In an anti-fascist book published in Paris in 1934, the sentence "Hitler commands what Rosenberg wants" was ascribed to a Hitler biographer .

This image remained unchallenged until the 1960s. Then Joachim Fest formulated his judgment based on the memories of Albert Speer . Fest quoted, for example, that Rosenberg had only been dismissed by Hitler as a “narrow-minded Balte who thinks in a terribly complicated way” - his importance did not seem to have been as great as had previously been assumed. In the same year as Fest's face of the Third Reich , Ernst Nolte's The Fascism in his epoch appeared , in which it was stated that National Socialism was essentially a reaction to communism, which was perceived as a threat, and was therefore not an ideology in its own right.

Younger German historians of the late 1960s who were oriented towards institutional and structural history were aiming in a similar direction (Anglo-Saxon history continued to focus on the problem area of ideology, but was initially hardly received in Germany). Reinhard Bollmus and Hans-Adolf Jacobsen used the offices and agencies headed by Rosenberg to work out that National Socialism did not establish a monolithic leadership state, but rather a polycracy without a clear hierarchy in which people, offices and authorities fought each other. Reinhard Bollmus, who in 1970 still tended to overshadow Rosenberg's importance during the National Socialist era, wrote, however:

“Rather, Rosenberg himself determined all of his powers, as he believed they arose from the Führer mandate, and also determined his areas of activity without instructions from a higher authority. Hitler and Hess did not approve, but neither did they dispute the correctness of the procedure. They gave no advice, did not set any specific tasks, imposed no bans and did not comment on the question of whether Rosenberg's interpretation of the worldview alone, in part, or even at all is authoritative. "

In Rosenberg's biography by Ernst Piper (2005), the emphasis was no longer placed on the easily tangible myth , but in the opinion of many historians less influential, as it was in the 1950s , but on the major role that Rosenberg played as a producer of anti-Semitic ideology and propaganda, about the Völkischer Beobachter and other publication organs. His widespread conspiracy theories, his daily agitation against everything Jewish, his paranoid but effective equation of Judaism and the Soviet regime justified for Piper the term "chief ideologist", which his book had in the subtitle, which had been ostracized for a long time.

Fonts (selection)

- Immorality in the Talmud . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1920, DNB 574670319 .

- The trace of the Jew through the ages . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1920, DNB 575892420 .

- The crimes of freemasonry. Judaism, Jesuitism, German Christianity . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1921, DNB 575892528 .

- Plague in Russia! Bolshevism, its heads, henchmen and victims . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1922, DNB 577383582 .

- The subversive Zionism explained on the basis of Jewish sources . Deutschvölkische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg 1922, DNB 575892668 .

- The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Jewish World Politics . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1922, DNB 575892307 ( excerpt ( memento from July 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive )).

- Nature, foundations and goals of the national-socialist German workers' party: The program of the movement . Deutscher Volksverlag Dr. E. Boepple, Munich 1923, DNB 577383639 .

- Center and Bavarian People's Party as enemies of the German state idea . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1924, DNB 362187436 .

- Stock exchange and Marxism or the master and the servant . Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1924.

- Houston Stewart Chamberlain as herald and founder of a German future . H. Bruckmann, Munich 1927, DNB 577383531 .

- Thirty November heads . Kampf-Verlag Gregor Strasser, Munich 1927, DNB 362187363 .

- The future path of a German foreign policy . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1927, DNB 575892684 .

- The swamp. Cross-sections through the “spirit” life of the November democracy . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1927, DNB 577383604 .

- The World Congress of Conspirators in Basel . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1927, DNB 577383620 .

- National Socialism and the Young German Order. A settlement with Artur Mahraun . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1927.

- World Masonic Politics in the Light of Critical Research . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1929, DNB 36218741X .

- The myth of the 20th century. A valuation of the soul and spirit struggles of our time . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1930, DNB 577383566 (194 editions until 1942).

- The essential structure of National Socialism: Foundations of the German rebirth . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1932, DNB 575892641 .

- Crisis and new building in Europe . Junker & Dünnhaupt, Berlin 1934, DNB 362187339 .

- The religion of the master Eckehart . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1934, DNB 575892358 (from: Myth of the 20th Century ).

- To the dark men of our time. An answer to the attacks on the "myth of the 20th century" . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1935, DNB 575891882 (33 editions up to 1941).

- The decisive world struggle: Speech at the party congress in Nuremberg in 1936 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1936, DNB 575892536 .

- Blood and Honor Volume I. A struggle for German rebirth. Speeches and essays from 1919–1933 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1936, DNB 575891807 (24 editions until 1941).

- Blood and Honor Volume II. Design of the Idea. Speeches and essays from 1933–1935 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1936, DNB 575892005 .

- Protestant pilgrims to Rome. The betrayal of Luther and the “myth of the 20th century” . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1937, DNB 575892382 .

- The struggle between creation and destruction: Congress speech at the Labor Party Congress on September 8, 1937 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1937, DNB 575892102 .

- Blood and Honor Volume III. Struggle for power. Articles from 1921–1932 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1937, DNB 575892064 .

- Shape and life . Niemeyer, Halle / Saale 1938.

- Weltanschauung and doctrine of faith [Lecture given on November 4, 1938 at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg] . Niemeyer, Halle / Saale 1939, DNB 362187398 .

- The historical meaning of our struggle: Speech to soldiers on the Western Front (April 16, 1940), from: Knapsack of the High Command of the Wehrmacht, Domestic Department; Volume 1 1939/40, issue 9 . M. Müller, Berlin 1940, DNB 365055441 .

- Blood and Honor Volume IV. Tradition and Present. Speeches and essays from 1936–1940 . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1941, DNB 575892471 .

- The party program: nature, principles and goals of the NSDAP . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1939, DNB 575892269 (present: 20th edition).

- Gold and blood. Speech on November 28, 1940 in the French Chamber of Deputies in Paris . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1941, DNB 36218724X .

- Writings and Speeches Volume 1. Writings from the years 1917–1921 . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1943, DNB 367791382 .

- Writings and Speeches Volume 2. Writings from the years 1921–1923 . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich 1943, DNB 367791390 .

- Friedrich Nietzsche. Address at a memorial service on the occasion of Friedrich Nietzsche's 100th birthday on October 15, 1944 in Weimar . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1944.

- Plague in Russia: Bolshevism, its heads, henchmen and victims: Abridged published by Georg Leibbrandt . 5th edition. Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich 1944, DNB 575892293 (abridged edition!).

- Portrait of a human criminal: Based on the memoirs of the former Reich Minister Alfred Rosenberg . Zollikofer, St. Gallen 1947, DNB 452703379 .

- Last records . Plesse-Verlag, Göttingen 1955, DNB 575891793 (contains four blackened pages for reasons of §130 StGB).

- Alfred Rosenberg's political diary from 1934/1935 and 1939/1940. Edited and explained by Hans-Günther Seraphim after the photographic reproduction of the manuscript from the files of the Nuremberg Trial. Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1956, DNB d-nb.info .

- Greater Germany, dream and tragedy. Rosenberg's criticism of Hitlerism . Self-published by H. Härtle, Munich 1970, DNB 457972297 (contains Rosenberg's last notes from the Nuremberg prison in 1946).

- Selected Writings: Edited and introduced by Robert Pois . Cape, London 1970, DNB 57813098X .

- Race and race history, and other essays / Edited and introduced by Robert Pois . Harper Torchbooks, New York 1974, DNB 100907525X .

- Jürgen Matthäus , Frank Bajohr (ed.): Alfred Rosenberg: The diaries from 1934 to 1944. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2015, ISBN 978-3-10-002387-2 .

- editorial staff

- National Socialist monthly issues . Central political and cultural magazine of the NSDAP . Zentral-Verlag der NSDAP, Munich, DNB 011465093 (1930–1934, then publisher until 1944).

- Volkish observer . Franz-Eher-Verlag, Munich, DNB 012107425 (1923-1938).

- The world struggle. Monthly for world politics, folk culture and the Jewish question of all countries . Hoheneichen-Verlag, Munich, DNB 012799335 (1924-1944).

literature

- Biographical approaches and overall presentations

- Serge Lang , Ernst von Schenck: Portrait of a human criminal. Based on the memoirs of the former Reich Minister Alfred Rosenberg. St. Gallen 1947, DNB 452703379 . (Annotated original excerpts from Rosenberg's notes during the Nuremberg Trial ; in the case of the last notes, the quotations without deletions.)

- Reinhard Bollmus: The Rosenberg Office and its opponents. Studies on the power struggle in the National Socialist system of rule. Stuttgart 1970, DNB 456157557 (2nd edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-54501-9 , evaluation of source material; some of the results no longer correspond to more recent Rosenberg research).

- Reinhard Bollmus: Alfred Rosenberg. Chief ideologist of National Socialism? In: Ronald Smelser (Ed.): The brown elite. 22 biographical sketches. Volume 1, WBG , 1989, ISBN 3-534-14460-0 , p. 223 ff.

-

Ernst Piper : Alfred Rosenberg. The prophet of war of souls. The devout Nazi in the ruling elite of the National Socialist state. In: Michael Ley, Julius H. Schoeps (ed.): National Socialism as a political religion. Philo-Verlags-Gesellschaft, Bodenheim 1997, ISBN 3-8257-0032-1 .

- Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-148-0 . (2007, ISBN 978-3-570-55021-2 ) (Gesamtdarstellung. Zugl. Habil. Phil. Univ. Potsdam 2005; partly online: The factual notes and entire literature section, p. 652 ff. ( Memento vom March 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 625 kB)

- Frank-Lothar Kroll: Alfred Rosenberg. The ideologist as a politician. In: Michael Garleff (Ed.): Baltic Germans: Weimar Republic and Third Reich. Böhlau, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-412-12199-1 , pp. 147–166.

- Reinhard Bollmus: Rosenberg, Alfred Ernst. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , pp. 59-61 ( digitized version ).

- Konrad Fuchs: Rosenberg, Alfred. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 24, Bautz, Nordhausen 2005, ISBN 3-88309-247-9 , Sp. 1230-1232.

- Dominik Burkard: Heresy and Myth of the 20th Century. Rosenberg's National Socialist Weltanschauung before the tribunal of the Roman Inquisition . (= Roman Inquisition and Index Congregation. 5). Schöningh, Paderborn 2005, ISBN 3-506-77673-8 .

- Volker Koop: Alfred Rosenberg. The pioneer of the Holocaust. A biography. Böhlau-Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-50549-3 .

- Approaches critical of ideology

- Raimund Baumgärtner: Weltanschauung struggle in the Third Reich. The dispute between the churches and Alfred Rosenberg . Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-7867-0654-9 .

- Harald Iber: Christian Faith or Racial Myth. The engagement of the Confessing Church with Alfred Rosenberg's "The Myth of the 20th Century" . Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1987, ISBN 3-8204-8622-4 .

- Claus-Ekkehard Bärsch : Alfred Rosenberg's "Myth of the 20th Century" as a political religion . In: Hans Maier, Michael Schäfer (ed.): “ Totalitarianism ” and political religions. Concepts of dictatorship comparison . Volume 2, Paderborn 1997 (review in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft. 47th year, 1999, issue 4).

- Miloslav Szabó: Race, Orientalism and Religion in Alfred Rosenberg's anti-Semitic view of history. In: Werner Bergmann , Ulrich Sieg (ed.): Antisemitic historical images. (= Anti-Semitism: History and Structures. Volume 5). Klartext , Essen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8375-0114-8 , pp. 211-230.

- Special monographs

- Hanns Christian Löhr: Art as a weapon - The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, ideology and art theft in the “Third Reich”. Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-7861-2806-9 (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg).

- Willem de Vries: Art theft in the West 1940-1945. Alfred Rosenberg and the special staff for music. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-596-14768-9 (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg).

- Andreas Zellhuber: "Our administration is driving a catastrophe ...". The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories and German occupation in the Soviet Union 1941–1945. Vögel, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-89650-213-1 . ( Review) .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alfred Rosenberg in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alfred Rosenberg in the German Digital Library

- Alfred Rosenberg in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Newspaper article about Alfred Rosenberg in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- The annotation and literature section of the Piper book (PDF; 625 kB). Almost complete literature list by and about A. R., ideal for searching through (also contains A. R's products that have not been included in compilations)

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry on Alfred Rosenberg. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

Biographies

- Daniel Wosnitzka: Alfred Rosenberg. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography ( memento of November 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on Shoa.de

- Dietmar Gottfried: Hitler's chief ideologist Alfred Rosenberg and “The Myth of the 20th Century”. on: Telepolis . 5th August 2012.

Discussion: Ernst Piper's book "Alfred Rosenberg - Hitler's chief ideologist"

- Random House ( Memento from April 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) - Book information, quotations and 40 pages of excerpts

- Private website Ernst Piper ( Memento from September 1, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) - excerpt from the chapter "People's state or worldview dictatorship?"

- Compass - excerpt from the chapter "From Myth to Myth"

- Stern - short book review

Scientific papers

- Social Sciences (UCLA) - Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917–1945. Los Angeles 1999 (PDF; 173 kB).

Alfred Rosenberg's diary

-

Diary of Alfred Rosenberg , 425 handwritten pages, which are also available as a transcript.

- Since 2013, the years 36 to 44 have been documented by entries from April 1936 to December 1944, which were in R. Kempner's (the deputy of the chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial (IMT) in Nuremberg). It is now archived in the USHMM .

- Frank Engehausen: "Rosenberg, your big hour has now come!" - The establishment of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories in Alfred Rosenberg's diaries , online: Officials of the National Socialist Reich Ministries , March 19, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ^ Entry in the baptismal register of the Nikolaikirche zu Reval (Estonian: Tallinna Niguliste kirik).

- ^ Manfred Weißbecker : Alfred Rosenberg. "The anti-Semitic movement was only a protective measure ...". In: Kurt Pätzold , Manfred Weißbecker (ed.): Steps to the gallows. Life paths before the Nuremberg judgments. Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-86189-163-8 , p. 171 (on this in detail: Baumgärtner: Weltanschauungskampf im Third Reich. 1977, p. 6 ff.); Walter Laqueur: Germany and Russia. Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1965, p. 93.

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg November 14, 1945–1. October 1946. Volume V, Munich / Zurich 1984, p. 53 ff.

- ↑ Eduard Gugenberger: messenger of the apocalypse. Visionaries of the Third Reich. Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-8000-3840-4 , p. 196.

- ↑ Toomas Hiio: Coming back to Alfred Rosenberg: Comments on a new biography. In: Research on Baltic history. 13, 218, pp. 161-170.

- ↑ Robert Wistrich : Who was who in the Third Reich. Supporters, followers, opponents from politics, business, military, art and science. Harnack Verlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-88966-004-5 , p. 229.

- ^ A b Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-148-0 , p. 21 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Bollmus: The office of Rosenberg and its opponents. Studies on the power struggle in the National Socialist system of rule. Stuttgart 1970, DNB 456157557 , p. 254; Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, DNB 575891793 , p. 167.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, p. 47.

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg November 14, 1945–1. October 1946. Volume XI, Munich / Zurich 1984, p. 493.

- ^ A b Johannes Baur: The Russian Colony in Munich 1900–1945: German-Russian Relations in the 20th Century. Harrassowitz Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-447-04023-8 , p. 273.

- ^ A b Walter Laqueur: Germany and Russia. Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1965, p. 93.

- ^ A b Alfred Rosenberg: Writings and speeches . Volume 1, with an introduction by Alfred Baeumler, Munich 1943, p. XXXIII.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, p. 14 f.

- ^ A b Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, p. 16.

- ^ A b Christiane Althoff: "The results of prehistoric research are the old testament of the German people". Prehistory and early history in the schools of the Third Reich. In: Christiane Althoff, Jochen Löher, Rüdiger Wulf (eds.): You too belong to the Führer. "National political education" in the schools of the Nazi dictatorship. Dortmund 2003, ISBN 3-00-005838-9 , p. 73 f.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey : Religion in Transition. Germany 1870-1918. Munich 1988, ISBN 3-406-33119-X , p. 139; Klaus Vondung: The Apocalypse in Germany. Munich 1988, ISBN 3-423-04488-8 , p. 62.

- ↑ a b c d Alfred Rosenberg: Last records. Göttingen 1955, pp. 12 ff., 32 ff., 38, 42, 274.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2005, p. 24 f .; Alfred Rosenberg: Rubonia in exile . Self-published, 1925.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, p. 18. (Rosenberg described Glasenapp's biography as "fundamental".)

- ↑ Joachim Köhler: Wagner's Hitler. The prophet and his executor. 2nd Edition. Munich 1997, ISBN 3-89667-016-6 ; Hartmut Zelinsky: Richard Wagner's “fire cure” or the “new religion” of “redemption” through “destruction”. In: Heinz-Klaus Metzger, Rainer Riehn (Ed.): Richard Wagner. How anti-Semitic can an artist be? (= Music Concepts. Volume 5). 3. Edition. Munich 1999, pp. 79-82.

- ^ The Nuremberg Trial, afternoon session April 15, 1946 , on Zeno.org.

- ↑ Hans -P. Hasenfratz: The religion of Alfred Rosenberg. In: Numen. Vol. 36, Fasc. 1 (Jun. 1989), pp. 113-126.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted by Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , pp. 81-82).

- ↑ a b c d Alfred Rosenberg: Writings and speeches . Volume 1, with an introduction by Alfred Baeumler, Munich 1943, pp. 4–124. (Originals of these writings are also in Paris, copies in the Federal Archives in Berlin.)

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The Russia Complex. The Germans and the East 1900–1945. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53512-7 , p. 268.

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted by Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , p. 82).

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted by Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , p. 347).

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted: Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , pp. 82-83).

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Germany and Russia. Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1965, p. 87; see. Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, p. 61 f.

- ^ Anna-Christine Brade: Kundry contra Stella. Offenbach versus Wagner. Bielefeld 1997, ISBN 3-89528-168-9 , p. 12 ff.

- ^ Wolfdietrich Rasch: The literary decadence around 1900. Munich 1986, ISBN 3-406-31544-5 ; George L. Mosse : The image of the man. To the construction of modern masculinity. Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-7632-4729-7 , p. 108 ff.

- ↑ Claus-Ekkehard Bärsch: The political religion of National Socialism . Fink-Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7705-3172-8 , p. 211 ff.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: Writings and speeches . Volume 1, with an introduction by Alfred Baeumler, Munich 1943, p. XIV.

- ^ Peter M. Manasse: Deported archives and libraries. The activity of the task force Rosenberg during the Second World War. St. Ingbert 1997, ISBN 3-86110-131-9 , p. 15.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-55021-2 , p. 34.

- ^ A b Alfred Rosenberg: Last Notes. Göttingen 1955, pp. 66, 71, IMG 1984, Volume XVIII, p. 81.

- ^ A b Johannes Baur: The Russian Colony in Munich 1900–1945: German-Russian Relations in the 20th Century. Harrassowitz Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-447-04023-8 , p. 279.

- ↑ Johannes Baur: The Russian Colony in Munich 1900-1945: German-Russian Relations in the 20th Century. Harrassowitz Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-447-04023-8 , p. 272.

- ↑ On this work Francis R. Nicosia : A Useful Enemy. Zionism in National Socialist Germany 1933–1939. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . 374. Jg. 1989, No. 3, p. 374. The font was published in 1922 by the “Deutschvölkische Verlagsanstalt” Hamburg, which was owned by the federal management of the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund . New edition in 1938 by Franz-Eher-Verlag .

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted by Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , p. 95).

- ↑ Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917–1945. 2005, ISBN 0-521-84512-2 , p. 223.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the Jewish world politics . Munich 1933, p. 133; quoted according to Norman Cohn : The struggle for the millennial kingdom. Francke, Bern 1961, p. 272.

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company 1965 (Reprinted: Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , pp. 131, 132).

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company 1965 (Reprinted: Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , p. 128).

- ↑ Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917–1945. 2005, ISBN 0-521-84512-2 , p. 139.

- ↑ a b Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917–1945. 2005, ISBN 0-521-84512-2 , p. 138.

- ^ Walter Laqueur: Russia and Germany. A Century of Conflict. Little Brown and Company, 1965 (Reprinted by Transaction Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-88738-349-1 , p. 89).

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The Russia Complex. The Germans and the East 1900–1945. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53512-7 , p. 272.

- ^ Richard Pipes: Russia under the Bolshevik Regime. 1994, ISBN 0-679-76184-5 , p. 499.

- ^ Robert Conquest: The Harvest of Sorrow. Arrow Edition, 1988, ISBN 0-09-956960-4 , p. 24.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-55021-2 , p. 58.

- ↑ Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917–1945. 2005, ISBN 0-521-84512-2 , pp. 238, 278.

- ↑ Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): Führer befiehl ... self-testimonies from the "fighting time" of the NSDAP . Grondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1991, pp. 68-72.

- ^ Wolfgang Mück: Nazi stronghold in Middle Franconia: The völkisch awakening in Neustadt an der Aisch 1922–1933. (= Streiflichter from the local history. Special volume 4). Verlag Philipp Schmidt, 2016, ISBN 978-3-87707-990-4 , p. 266.

- ↑ Walter Künneth: Answer to the Myth. The choice between the Norse myth and the biblical Christ. Berlin 1935.

- ↑ Walter Grundmann: God and Nation. An evangelical word on the will of National Socialism and Rosenberg's interpretation of the meaning. Berlin undated

- ↑ Quoted in: Hans-Günther Seraphim: Alfred Rosenberg's political diary from 1934/35 and 1939/40. Göttingen / Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1956, p. 32 (cited source: Document PS-003, reproduced in: IMT, Volume XXV, p. 15 ff.).

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : The Olympic Games 1936 and the world opinion: their foreign policy significance with special consideration of the USA. (= Sports science work. Volume 7). Bartels & Wernitz, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-87039-925-2 , pp. 176f.

- ↑ The Amber Room from the Catherine Palace near Saint Petersburg was not captured by Rosenberg's people. Hanns Christian Löhr: Art as a weapon. The task force Reichsleiter Rosenberg. Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-7861-2806-9 , p. 61.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. P. 515.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Pp. 520-525.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. P. 521.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. P. 531.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär , Winfried Vogel : Serving and earning. Hitler's gifts to his elites. Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-10-086002-0 .

- ^ A b Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg. Hitler's chief ideologist. Munich 2005, p. 620.

- ↑ Stephan Link: "Rattenlinie Nord". War criminals in Flensburg and the surrounding area in May 1945. In: Gerhard Paul, Broder Schwensen (Hrsg.): Mai '45. End of the war in Flensburg. Flensburg 2015, p. 20 f.

- ↑ Joe Heydecker, Johannes Leeb: The Nuremberg Trial. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2015.

- ^ First edition of the Berliner Zeitung of May 21, 1945, p. 3.

- ^ Ernst Piper : Alfred Rosenberg, Hitler's chief ideologist. 2005, p. 621.

- ↑ State Center for Civic Education Schleswig-Holstein (ed.): The downfall 1945 in Flensburg. ( Memento from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (Lecture on January 10, 2012 by Gerhard Paul ), p. 19.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Alfred Rosenberg, Hitler's chief ideologist. 2005, p. 621.

- ↑ Sven Felix Kellerhoff: What Rosenberg himself said about his diary . In: Welt Online . June 20, 2013 ( welt.de [accessed July 9, 2016]).

- ↑ Thomas Darnstädt : A stroke of luck in history . In: Der Spiegel . No. 14 , 2005, pp. 128 ( online ).

- ^ The Alfred Rosenberg diary. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed July 9, 2016 .

- ^ Diaries of Hitler's chief ideologues emerged . In: ZEIT Online . June 13, 2013 ( zeit.de [accessed December 27, 2018]).

- ↑ Missing documents: US authorities present diaries. In: Spiegel online . 13th June 2013.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg diary. on: collections.ushmm.org/

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg - Diaries of a power man . In: Deutschlandfunk.de . April 16, 2015 ( deutschlandfunk.de [accessed December 27, 2018]).

- ↑ Hans-Günther Seraphim (Ed.): Alfred Rosenberg's political diary 1934/35 and 1939/40. Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1956.

- ↑ Walter Mehring , Paul L. Urban : Nazi leaders look at you . More here

- ↑ Nazi leaders look at you (1934), p. 80.

- ↑ Reinhard Bollmus: The office of Rosenberg and its opponents. Studies on the power struggle in the National Socialist system of rule. Munich 1970, p. 69.

- ↑ The speech sums up Rosenberg's view briefly: Western society is controlled by “gold”, capitalists, variable contracts, legal principles; the structural element of Nazi society, on the other hand, is “blood”, which is viewed as static, cf. Blood and soil .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rosenberg, Alfred |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rosenberg, Alfred Ernst (full name); Eidhalt, Rolf (pseudonym); Розенберг, Альфред Вольдемарович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (NSDAP), MdR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 12, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Reval |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 16, 1946 |

| Place of death | Nuremberg |