Parzival

Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach is a verse novel of Middle High German courtly literature , which was written between 1200 and 1210. The work comprises about 25,000 verses rhymed in pairs and is divided into 16 books in the modern editions.

The Aventiurs , the adventurous fortunes of two knightly main characters - on the one hand, the development of the title hero Parzival (from the old French Perceval ) from the ignorant in the fool's dress to the Grail King, on the other hand, the dangerous tests for the Arthurian knight Gawain are told in artfully interlinked storylines of a double novel structure .

Thematically, the novel belongs to the so-called Arthurian epic , whereby the inclusion of Parzival in the round table of the mythical British king only appears as a transit point in the search for the Grail , but then becomes a prerequisite for his determination as the Grail King.

The material was worked on in literary terms, but also in the fine arts and music; Richard Wagner's adaptation for music theater achieved the most lasting effect with his Parsifal stage festival (world premiere in 1882).

Subject

The Parzival material deals with complex topics. It is about the relationship between society and the world, the contrasts between the world of men and women, the tension between courtly society and the spiritual community of the guardians of the Grail, guilt in the existential sense, love and sexuality, redemption, salvation, healing and paradise fantasies . The development of the protagonist from his self-centeredness to the ability to empathize and to break out of the narrow dyad with Parzival's mother Herzeloyde is taken up according to a psychoanalytic focus . Parzival is initially an ignoramus and sinner, who in the course of the plot reaches knowledge and purification and on his second visit to the Grail Castle Munsalvaesche can make up for the stigma of neglecting questions (the pitying question about the suffering of his uncle, the Grail King). Parzival is the redeemer figure in the Grail myth.

Classification in literary history

History and structure

Wolframs wilde maere stands out among the verse novels of Middle High German literature - polemically disparagingly referred to by Gottfried von Straßburg in Tristan's "literature excursion" - in several ways:

- With its complex structure of meaning and the elaborate narrative composition, Parzival is not an "easy read" from the start; Nevertheless, with over 80 textual testimonies, the work can be said to have had a unique history of impact as early as the Middle Ages. Joachim Bumke (see below: Literature ) speaks of a “literary sensation”, which must have been the work, cited and copied more often than any other in the 13th century.

- The division into 16 books and 827 sections of 30 verses is due to the first critical edition by Karl Lachmann (1793–1851) from 1833. This edition is valid to the present day and has not been replaced. Before that, Christoph Heinrich Myller , a student of Johann Jacob Bodmer , had attempted an edition. Ludwig Tieck's 1801 plan to edit Wolfram's Parzival was not realized.

- Wolfram deals with all the common problems of his literary epoch (above all, love issues, aventiure demands, suitability to be a ruler, religious determination ) - sometimes critically ironic, sometimes coming to a head in a new way for his time; the novel is therefore of exemplary importance for the complex of topics of court literature as a whole.

- The author follows a multitude of other storylines parallel to the main story around Parzival. In ever new "dice throws" ( Schanzen , Parz. 2,13 - Wolfram's metaphor in Parzival's prologue in relation to his own narrative method) he plays through the political, social and religious problems Parzival is faced with with other protagonists and thus unfolds the novel into a comprehensive anthropology.

Wolfram himself was aware that his often erratic, associative narrative style was new and unusual; He compares it with the “hooking of a hare on the run from ignoramuses” ( tumben liuten , Parz. 1.15 ff) and thereby confidently emphasizes, again to Gottfried, who uses the same metaphor derisively and derisively, his conspicuous artistic linguistic formative power as well as content and thematic Imagination. What is striking and unusual for a medieval author is the confident rearrangement of the material found by Wolfram. The processing takes place according to one's own literary ideas and intentions.

The Parzival follows a double novel structure with a long prologue. After the first two books, which are devoted to the prehistory of the main plot, i.e. the adventures of Gahmuret, Parzival's father, Wolfram begins to tell about the childhood of his protagonist. This is followed later by the change to the Gawan story, which is interrupted by Parzival's visit to the hermit Trevrizent and then resumed. The content of the last two books is dedicated to Parzival.

Wolframs Parzival and Chrétiens Perceval

The main source of Parzival is the unfinished verse novel Perceval le Gallois ou le conte du Graal / Li contes del Graal by Chrétien de Troyes , written around 1180 and 1190. Wolfram himself distances himself in the epilogue from Chrétien, and mentions the work of a "Kyot" several times as Template, which he provides with an adventurous story of how it came about. But since such a "Kyot" could not be identified outside of Wolfram's poetry, this information is classified in research as a source fiction and literary coquetry of the author.

The plot of the Parzival is extensively expanded compared to the original, in particular by the framing with the introductory prehistory of Parzival's father Gahmuret and the final events in the encounter between Parzival and his half-brother Feirefiz . The embedding in the family history serves - beyond the pure pleasure in telling stories - the increased causal motivation of the action. Wolfram comes to almost 24,900 verses compared to the 9,432 verses in Chrétien.

In those passages in which Wolfram Chrétien follows in terms of content (Book III to Book XIII), he goes much more freely and self-confidently to the retelling than other contemporary authors (e.g. Hartmann von Aue , whose Arthurian novels Erec and Iwein are adaptations of Chrétien's novels) . The text volume of the original was doubled to around 18,000 verses because Wolfram allows his protagonists to reflect on ethical and religious issues in much more detail and expresses himself as a reflective narrator on the events of the fictional plot. He ties the characters into a network of relationships and assigns names to them.

See also the Cymric legend Peredur fab Efrawg ("Peredur, son of Efrawg"), which also deals with this topic. The mutual influence has not yet been fully clarified.

Action - overview

Parzival's upbringing as a knight and his search for the Grail is - as the narrator emphasizes several times - the main theme of the plot, but Wolfram follows Gawan's knight ride almost equally, but contrasts it . While Gawan appears consistently as the almost perfect knight and has always proven himself successful in numerous adventures in holding the guilty of abuses of the world order to account and restituting this order, Parzival not only experiences adventures but also extreme personal conflict situations and becomes - out of ignorance or due to of misinterpretations of statements and situations - repeatedly guilty of yourself. But it is precisely he, who has to endure the consequences of his wrongdoing for many years, who in the end gains control of the Grail. The epic ends with an outlook on the story of Parzival's son Loherangrin (see Wagner's Lohengrin ).

With the division of the text into so-called 'books', the following overview is based on the established organizational principle of Karl Lachmann , the first 'critical' editor of Parzival , on whose edition, however, which has since been revised, research is still dependent.

Wolfram's prologue (Book I, verses 1.1 to 4.26)

Beginning: parable of magpies (verses 1, 1–2, 4)

Wolfram begins his Parzival with the parable of magpies (verses 1,1-1,14). Here he uses the analogy of the two-tone plumage of the magpie agelstern ( Middle High German ) based on the obvious juxtaposition of fickleness and loyal devotion. Here he comes to the conclusion that there is not just black and white, good and bad, but that all of this merges into one another like the plumage of a magpie.

Addressees and lessons from the Parzival (verses 2.5-4.26)

The addressees are named. The tournament knights should reflect on the high ideals of chivalry and the women learn from them who they give their love and honor to. This is a hymn of praise to those knightly virtues that Parzival will later find: honor, loyalty and humility.

The prehistory: Gahmurets Ritterfahrten (Book I – II)

Wolfram introduces his novel with the broadly painted story of Gahmuret , Parzival's father.

As the second-born son, when his father Gandin, King of Anschouwe died , he remained without an heir and moved to the Orient in search of knightly probation and fame. First he serves the Caliph of Baghdad, then he helps the black-skinned Queen Belacane against her besiegers, who want to avenge the death of Isenhart, who was killed in unrewarded service for her. Gahmuret wins and marries Belacane, thus becoming king of Zazamanc and Azagouc , fathering a son named Feirefiz , but soon leaving Belacane in search of further adventures. Back in Europe, Gahmuret takes part in a tournament in front of Kanvoleis , in which he wins the hand of Queen Herzeloyde and the rule over her lands Waleis and Norgals . But from here, too, Gahmuret soon goes on a knightly ride again, enters the caliph's service again, where he is finally killed by a spear that penetrates his diamond helmet, which has been made soft with goat's blood.

Gahmuret leaves both women so quickly that he does not live to see the birth of his two sons: neither those of Belacane's son Feirefiz , spotted like a magpie all over his body, nor that of Herzeloyde's son Parzival (which means “in the middle (through) through ”).

Youth and knightly education of Parzival (Book III – V)

At the news of Gahmuret's death, Herzeloyde desperately retreats with Parzival to the forest wasteland of Soltane . There she brings up her son in quasi-paradisiacal innocence and ignorance; He even learned his name and origins later from his cousin Sigune shortly before his first appearance at the Artus Court. The mother very consciously keeps him informed about the world and life outside the forest, in particular does not prepare him for any of the ethical, social and military demands that he would face as a knight and ruler. The fact that Parzival is noticed later in the courtly world is primarily due to his external attributes: the narrator repeatedly emphasizes his striking beauty and astonishing physical agility and strength and tells the impression that these advantages make on Parzival's surroundings.

Herzeloyde's attempt to keep the boy away from the dangers and temptations of knighthood fails thoroughly: When Parzival first accidentally encounters knights, Herzeloyde cannot prevent him from going to the Artus Court to become a knight himself. In the hope that her son will return to her if he only has enough bad experiences in the world, she equips him with the clothes and equipment of a fool and gives him final teachings on the way, the verbatim observance of which he works together with the naive demeanor and the fool's clothing become the comical caricature of a court knight. (For example, she advises him to greet everyone in a friendly way, which he then exaggerates by being picky about greeting everyone and adding, "My mother advised me.")

Immediately after Parzival left Soltane, the deficient upbringing caused a whole chain of misfortunes, without Parzival being aware of his personal share in it, his guilt, at this point in time. First of all, the pain of parting causes the mother's death, then Parzival - misunderstanding Herzeloyde's inadequate ministry - brutally attacks Jeschute , the first woman he meets, and steals her jewelry. For Jeschute, this encounter with Parzival becomes a personal catastrophe, because her husband Orilus does not believe her innocence, abuses her and exposes her to social contempt as an adulteress. Finally arriving at Artus Court, Parzival kills the "red knight" Ither - a close relative, as it turns out later - in order to get his armor and horse. For Parzival, the robbery of weapons means that he now feels like a knight; Significantly, however, he insists on wearing his fool's dress under his armor.

He does not do this until the next stop on his journey, with Prince Gurnemanz von Graharz . Gurnemanz instructs Parzival in the norms of knightly lifestyle and fighting techniques, here Parzival actually learns courtly behavior (gaining shame, taking off the fool's dress, rituals of Christian worship, "courtesy" and personal hygiene); Outwardly, he has all the prerequisites for being able to take a position in the world as ruler and husband. When he leaves Graharz after 14 days, Parzival is an almost perfect knight in the sense of the Arthurian world. However, by forbidding him to ask unnecessary questions, Gurnemanz also gives him a heavy mortgage on the way (see below). Impressed by Parzival's beauty and strength and his now perfect courtly demeanor, Gurnemanz wants nothing more than to marry him to his beautiful daughter Liaze (pronounced: Liaße) and to bind him as a son-in-law. But before that happens, Parzival rides out again. Although he promises to return full of gratitude, he never returns to the court and does not meet Gurnemanz again.

Parzival proves himself a knight when he frees the beautiful Queen Condwiramur in the town of Pelrapeire from the siege of intrusive suitors ; he wins the hand of the queen and thus dominion over the kingdom.

After he has put the kingdom in order, he leaves Condwiramurs again - like his father before the birth of his wife, but with her consent - to visit his mother, of whose death he does not yet know.

Parzival's failure in the Grail Castle - inclusion in the round table (Book V – VI)

When asked about a hostel for the night, Parzival on Lake Brumbane is referred by a fisherman to a nearby castle and experiences a number of mysterious events there: The castle's crew is obviously very happy about his appearance, but at the same time feels like in deeper Sadness. In the ballroom of the castle he meets the fisherman again; it is the lord of the castle, Anfortas , who suffers from a serious illness. Aloe wood fires burn because of the king's illness. Before the meal, a bleeding lance is carried across the room, causing loud complaints from the assembled court society. Then 24 young noblewomen carry out the precious cutlery in a complicated process, and finally the Grail is brought in by Queen Repanse de Schoye , a stone from Wolfram that mysteriously brings out the food and drinks like a " table-deck-you ". And at the end Parzival receives his own precious sword from the lord of the castle - a last attempt to encourage the silent knight to ask with which, according to the narrator, he would have redeemed the ailing king. As he had been impressed by Gurnemanz as courtly appropriate behavior, Parzival now suppresses any question in connection with the sufferings of his host or the meaning of the strange ceremonies.

The next morning the castle is deserted; Parzival tries in vain to follow the knights' hoof tracks. Instead, he meets Sigune for the second time in the forest, from whom he learns the name of the castle - Munsalvaesche - and the lord of the castle and that Parzival would even now be a powerful king with the highest social prestige if he asked the lord of the castle about his suffering and thus him and redeemed the castle society. When he has to admit to Sigune that he was incapable of a single compassionate question, she denies him all honor, calls him a cursed man and refuses any further contact. Immediately afterwards Parzival meets another lady for the second time: Jeschute. By swearing to Orilus that he had no love affair with her, he can correct his misconduct at the first meeting at least to the extent that Jeschute is socially rehabilitated and taken back as his wife.

Finally, there is another variation of the leitmotif: Parzival reaches Arthurian society for the second time. Arthur had set out to find the now famous “red knight”, and this time Parzival is included in the round table with all courtly honors; he has thus climbed the secular summit of the knightly career ladder. The round table gathers for a common meal, but only apparently all the previously told contradictions, misconduct and internal rivalries have been forgiven and overcome. In addition to Parzival, Gawan , Arthur's nephew, is another knightly hero in courtly esteem, his courage in battle and his noble dignity.

But exactly at this moment of maximum splendor and self-affirmation of the ideal noble society, two figures appear who, with bitter curses and reproaches against the honor of knight, destroy Gawan's and Parzival's cheerful mood and bring about the immediate end of the festive gathering: the ugly messenger of the Grail Cundrie la Surziere curses Parzival, laments his failure at the Grail Castle and describes his presence at the Artus Court as a disgrace for chivalrous society as a whole. Furthermore, she draws the attention of the group to the fact that the knightly world is by no means as well-ordered as the cheerful sociability might lead one to believe. Cundrie tells of the imprisonment of hundreds of noble women and girls at Schastel Marveile Castle , including the closest female relatives of Gawan and Arthur. Eventually Gawan is accused by Kingrimursel , the Landgrave of Schanpfanzun , of the insidious murder of the King of Ascalun and challenged to a court battle.

Parzival's superficial idea of God is shown in the fact that he attributes his failure at the Grail Castle to the inadequate care of God, who could have shown his omnipotence in order to redeem Anfortas and thus save his faithful servant Parzival from the shameful curse of Cundrie. As in a feudal relationship, Parzival resigns from God; this misjudgment of the relationship between God and man grows later into a real hatred of God.

The title hero leaves the round table immediately and embarks on a lonely search for the Grail for years. He thus becomes a marginal figure in the narrative of the following books, in the foreground of which are the Aventiurs Gawans.

Gawan's adventures in Bearosche and Schanpfanzun (Book VII – VIII)

The Parzival and Gawan plot vary the same basic problem from different perspectives: Both protagonists are challenged again and again as heroic knights to restore the order of the courtly world that has been lost. Parzival regularly fails in this task because his gradual knightly training and education turns out to be inadequate compared to the more difficult task that follows.

Gawan, on the other hand, embodies ideal knighthood from the very first appearance. He too has to deal with problems of court society in increasingly difficult tasks; all the difficulties into which he is plunged have their cause in conflicts of love and honor. Gawan, however, proves to be able to solve the problems that arise from this through diplomacy and struggles, even if he himself does not - like Parzival vice versa - cling to a spouse for years.

On the way to the court battle against the Landgrave of Schanpfanzun Kingrimursel in Ascalun , Gawan passes the city of Bearosche and witnesses preparations for war: King Meljanz von Liz besieges the city of his own vassal because Obie, the daughter of the city lord, has rejected his courtship . The situation is complicated by the fact that Gawan is initially covered with false accusations by Obie, completely unmotivated, that he is a cheat, but then after clarification is asked by the beleaguered prince for chivalrous assistance. Gawan's knighthood actually requires that this request be complied with, but on the other hand he does not want to be involved in the fighting because he feels the obligation to get to Ascalun in good time and unharmed . Obilot , Obie's little sister, finally succeeds with childlike charm in persuading Gawan to intervene in the fighting as her knight; and Gawan decides the war when he captures Meljanz. He shows himself to be a clever mediator when he hands the little Obilot over to the prisoners and thus successfully leaves it to her to reconcile Meljanz and Obie.

The central text passage, Obilot's wooing for Gawan's knightly assistance, is given a comical accent due to the extreme age difference between the two; Gawan playfully responds to Obilot's advances within the framework of courtly conventions. The next love adventure, however - partner is with Antikonie , the sister of the King of Ascalun , this time an attractive woman - develops into a serious danger for the hero's life. Gawan meets King Vergulaht , whose father he allegedly slain, while hunting, and the King recommends him to the hospitality of his sister in Schampfanzun . Gawan's barely disguised sexual desire and anticoniasis obvious counter-interest leads the two into a compromising situation; When they are discovered, the townspeople are mobilized against Gawan's alleged intention to rape. Because Gawan is unarmed, the two of them can only fight off the following attacks with great difficulty, Gawan's situation becomes completely untenable when King Vergulaht intervenes against him in the fight.

Gawan had, however, been assured of safe conduct from Kingrimursel until the court battle; therefore he now stands protectively in front of the knight and thus against his own king. The fierce discussions that followed in the king's advisory group led to a compromise that allowed Gawan to save face and leave the city freely: the court battle was postponed - it will ultimately no longer take place since Gawan's innocence has been proven - and Gawan is given the task of looking for the Grail in place of the king.

Parzival near Trevrizent - Religious instruction and enlightenment (Book IX)

If the narrator picks up the Parzival thread again, then four years have passed since the last appearance of the “Red Knight” in the background of the Aventiurs Gawans. Nothing has changed in Parzival's basic attitude: He still lives in hatred of God, who refused him the help to which he was obliged in Parzival's opinion at the decisive moment in the Grail Castle; he is still on the lonely search for the grail.

First, Parzival meets his cousin Sigune for the third time. This very lives of mourning for her dead lover Schianatulander and has now together with the coffin in a cell can be walled; from the Grail Castle she is provided with the essentials. The fact that she is now ready to communicate with Parzival again, to make up with him, is the first sign of a possible turn for the better in the fate of the title hero; However, despite the obvious proximity, he cannot yet find the Grail Castle.

Again a few weeks later, synchronized with the Christian history of salvation on a Good Friday , Parzival meets a group of Bußpilgern to him horrified by his appearance in arms that day and his rejection rates from God, a close in a cave holy dwelling " Man ”for help and the forgiveness of sins. Only this encounter with the hermit Trevrizent , a brother of his mother, as it turns out, brings the personal development of the hero - and that means: his knightly upbringing - to a conclusion. The long conversations of the following two weeks at Trevrizent differ significantly from the previous lessons of the title hero at Herzeloyde and Gurnemanz. They are much more extensive, but also fundamentally different from the earlier ones: By discussing the entire problem with Parzival in quasi maimic dialogues, he allows him to come to the decisive knowledge about the causes of his desolate condition.

Trevrizent's contribution essentially consists of questioning and clarification: As a correct understanding of God, he explains that God cannot be forced to give help to those who - like Parzival - think he can demand it, but rather out of divine grace and love for people grant out to him who humbly surrenders to God's will. The hermit, whose name is derived from Wolfram von Eschenbach of Trismegistus , further explains in detail the nature and effectiveness of the Grail; In summary: It is a precious stone that has life and youth sustaining powers, which are renewed annually on Good Friday by a wafer donated from heaven; sometimes a writing appears on the stone giving instructions, for example about who should be accepted into the Knighthood of the Grail. Trevrizent expressly denies the possibility of gaining the Grail through chivalrous deeds and battles, as Parzival or, in the meantime, Gawan attempt. Only those who are called by the Grail can become King of the Grail, and the community eagerly waits for such a message from the stone so that Anfortas can be redeemed from his sufferings. Parzival learns that he was chosen by the epitafum , the fading writing on the Grail, to redeem his uncle Anfortas by asking about his suffering. Trevrizent highlights the story of the fall , and in particular the story of Cain's fratricide against Abel , as exemplary of the sinfulness of mankind as a whole and the turning away from God. The revelation of Parzival's family history is related to this - Anfortas, who continues to suffer because of Parzival's failure to answer questions, is also his mother's brother, Herzeloyde died in mourning over the loss of Parzival, also the killed Ither, in whose armor Parzival is still in, was a relative - to the grave register of sins.

The days with Trevrizent in the spartan cave and with meager provisions become a consoling penance exercise - when Parzival leaves Trevrizent, he accordingly grants him a kind of lay absolution . With this, Parzival is apparently released from the sins of his past, at least these are no longer discussed as a burden for the hero in the further course of the story. But above all he is freed from hatred of God.

Gawan and Orgeluse (Book X-XIII)

Gawan rode around for about four years in search of the Grail and meets a lady with an injured knight named Urjans in her arms by a linden tree. Since he is a trained knight, Gawan also knows his way around medicine. He sees that the wound could cost the knight his life if the blood wasn't sucked out. So he gives the lady a reed from a linden box, who can save her loved one from death in this way (Wolfram describes a pleural puncture or thoracentesis here ). Gawan learns from the knight that Logrois Castle is nearby, and many knights ask for their love for its beautiful ruler, the organuse . So he rides a little further and sees a mountain with a castle. There is only one circular route up this mountain, which Gawan takes with his grail horse Gringuljete. Once at the top he meets Orgeluse, who is very repellent to him. Nevertheless, they ride out together and meet Malkreatür (German: bad creature ), Cundrie's brother. Gawan throws Malkreatür to the ground, which then remains there. After some scorn from Orgeluse towards Gawan, they ride on, Malkreatur's horse follows them. They come to the linden tree with the knight and Gawan gives him medicinal herbs that he had collected on the way, of course not without derision from Orgeluse. The knight jumps on Gringuljete, says that this is revenge for the scorn and ridicule that Gawan made him at Arthur's court. Because this knight had abused and desecrated a maiden without her being his. So the knight healed by Gawan rides away with his lover, and Gawan has no choice but to continue riding on Malkreatür's horse, a weak nag. Orgeluse continues to mock Gawan, and when they come to a river, the two separate, with Orgeluse crossing it without Gawan.

Gawan's fight against Lischoys Gwelljus

First Gawan sees the castle and its residents in the windows on the opposite bank of an adjacent river. The reason for his stay there is his still unfulfilled love for the organ . At her request, he should fight for the right to see the knight Lischoys Gwelljus again while she is already on the ferry to Terre marveile. Orgeluse uses a reference to the audience as an incentive for Gawan. This reference already suggests that the plot will shift in the direction of this scene.

At the ferryman Plippalinot

The fight and victory over Lischoys is observed by the virgins from the castle, but takes place in the normal world. With the victory, Gawan gets his grail horse back. With the crossing of the river Gawan crosses the dividing line between the world of Arthur and Terre marveile (German: magic land ). The ferryman who translates it is called Plippalinot and later tells Gawan, after he has taken him into his house, about Terre marveile; he describes it as a single adventure. Since Gawan asks the ferryman to Schastelmarveil (German: magic castle ) with great interest, he begins to refuse him further information because he is afraid of losing Gawan.

Through Gawan's persistence, an inverted relationship to the Parzival act becomes visible. Parzival misses the right question in the right place, while Gawan asks where not to ask.

When Gawan finally has Plippalinot and he answers, Plippalinot assumes that Gawan will then fight. That is why he first equips the knight with a heavy old shield before giving him the name of the country and describing its great dangers. He specifically emphasizes the lit marveile (magic bed) among the miracles. In addition to the shield, Plippalinot provides Gawan with wise advice, which later turns out to be very useful: Gawan should negotiate something with the merchant in front of the gates and give his horse in his care, always carry his weapons with him in the castle and wait and see lay down on Litmarveile.

This is exactly how Gawan will behave afterwards.

Gawan with the merchant

Arriving at the castle, Gawan realizes that he cannot pay for the goods offered there. The merchant then offers him to look after his horse so that he can try his luck. Then Gawan goes through the gate and enters the castle, which nobody prevents him. The huge inner courtyard of the palace has been abandoned, as has the rest of the palace. The ladies in the castle are not allowed to assist Gawan in his fight, and thus he cannot, as was usually the case in previous fights, draw his strength from the minne service, such as in the battle before Bearosche when he called the minne von Obilot used. At that time her love was his umbrella and shield, which he symbolically expressed by attaching a sleeve of her dress to one of his battle shields. It is noticeable here that the “use of shields” always plays an important role in Gawan's minne adventure.

The adventures in the magic castle

The first problem that Gawan has to overcome in the castle is the mirror-smooth floor, which was designed by Klingsor himself, but above all the litmarveile magic bed.

This smooth floor seems to symbolize the particularly dangerous path to love, which is very appropriately represented by the bed. The first attempt that Gawan makes to climb Litmarveile fails miserably. Only after a bold leap does he finally get onto the bed. This scene cannot be denied a certain comedy, it probably symbolizes the sometimes amusing efforts of some men for love ministry.

When the bed now rushes through the room like crazy to get rid of Gawan, the knight pulls the shield over him and prays to God. Here Gawan finds himself in a situation that would seem hopeless for a normal person, a helpless moment. The dangerously humiliating aspect of love should be pointed out. But since Gawan has already lived through all facets of love, he can stop the bed. But the dangers are not over yet. Because after the bed has been defeated, Gawan has to survive two more attacks, first from five hundred slingshots, then from five hundred crossbows. The five hundred slings and five hundred crossbows symbolize the powerful magic of Klingsor. Here the heavy equipment of the knights is more of a hindrance, it does its job in normal combat, but is powerless against love. Now a giant wrapped in fish skin comes into the hall, who insults Gawan in the most violent manner and also points out the danger that will ensue. Since the unarmed giant does not seem to be an appropriate opponent for an Arthurian knight, this insert probably serves to make a break in the type of attack clear.

The lion, who is now jumping in, immediately attacks Gawan brutally. The lion attacks Gawan severely, but he succeeds in chopping off a paw and finally killing him with a sword thrust through the lion's chest. The fight against the “king of animals” probably symbolizes the fight against the courtly itself. Gawan now collapses, wounded and injured, passed out on his shield.

This collapse on the shield means the end of the dangers. The castle has been captured, the spell broken. Gawan's shield in the lion fight, which stands for the embodiment of court society, stands for love. In the fight against Litmarveile, however, the roles are reversed: The magic bed, which embodies love, is the danger here, Gawan's chivalry is his protection.

Why Gawan?

In contrast to many other knights, Gawan manages to survive all the dangers in the castle safely because he is equipped with the right skills in all battles. First there is: experience in affairs of the minnee, and second: tactical skill. In addition, his heavy oak shield and the right prayer at the right time help him. The shield stands for right faith (Eph. 6:16: "But above all, take hold of the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all fiery arrows of evil.").

Klingsor (Duke Terra di Lavoro)

Klingsor (also: Klinschor ) is named for the first time by Plippalinot as the lord of the land, which is "even aventure". Klingsor, the lord of Schastelmarveile , only appeared in connection with magic until the castle was conquered . You can already find out important details from King Kramoflanz. So he slew Zidegast, her lover, in order to win the love of the Duchess (Orgeluse) for himself. After this act, the Duchess seeks his life. She had many mercenaries and knights in her service whom she sent out to kill Kramoflanz. Among them was the knight Anfortas, who in their service contracted his painful wound. He also gave Orgeluse the splendid merchant's booth (which now stands in front of Schastelmarveile). Fearing the mighty magician Klingsor, she gave him the precious merchant class on the condition that her love and the stand are publicly exposed as an additional price for the conqueror of the adventure. Orgeluse wanted to attract Kramoflanz and send him to death.

However, Kramoflanz doesn't have a bad relationship with Klingsor either, as his father Irot gave him the mountain and the eight miles of land for the construction of Schastelmarveile. And so Kramoflanz saw no reason to conquer Schastelmarveile. So far we have learned that Klingsor must have enjoyed training in black magic, but that on the other hand, he is also a sovereign who is no stranger to courtly manners.

Now that Gawan has won Orgeluse's favor, he returns to Schastelmarveile to ask the wise Arnive about Klingsor. He wants to know how someone could manage to work with such a ruse. Gawan learns from Arnive that Terremarveile is not the only area over which Klingsor rules or ruled. His homeland is Terre de Labur, and he comes from the family of the Duke of Naples. She goes on to say that Klingsor was a duke and enjoyed a high reputation in his city of Capua, but suffered an enormous loss through an adulterous love affair with Queen Ibilis of Sicily, which ultimately drove him to sorcery. He was caught red-handed by King Ilbert with his wife, so that the latter did not know what to do other than to castrate him.

As a result of this disgrace done to him, Klingsor set out for the land of Persida, where sorcery more or less originated. There he apprenticed until he became a great magician. The reason for building Schastelmarveile was revenge. With this Klingsor wanted to destroy the happiness of all members of court society in order to avenge his emasculation. He tries to carry out this vengeance with the help of all means by which he has power thanks to his magic. Due to his own shame and failure to love love, he recreates the adventures of conquering the castle and the dangers of love-making. Despite his life as a black magician, he always remains courtly to a certain extent, which can be seen when it comes to the transition from Terremarveile to Gawan. When Gawan becomes lord of the land and its riches, Klingsor disappears from both the area and the book.

Comparison between Schastel marveile and Munsalvaesche

In the book Munsalvaesche embodies the castle of God and thus the Grail Castle. Schastel marveile, on the other hand, embodies pure evil. Both exist on "our world", which makes it clear that all bad and good are contained in us. Klingsor's ambiguous personality is another example of this. Furthermore, Klingsor and Anfortas have a very similar problem. Both get into very great distress due to the love service. They both lose their ability to pass on life to themselves.

Klingsor then goes the "path of evil" and begins his campaign of revenge against love, using black magic. Anfortas, on the other hand, turns to the Grail and takes the "path of penance", which is a symbol of the strong contrasts between the two castles.

Summary

The Schastelmarveile episode combines several topics. In it the dangers of the ministry are presented in a more or less abstract way. A scene formation corresponding to the Parzival action is built up through the questioning behavior of Gawan or Parzival and through the mirror-image representation of Klingsor and Anfortas as a contrast between the Grail world and Terremarveile. Both Klingsor and Anfortas succumbed to love. However, while Anfortas chooses the path of repentance, Klingsor takes the path of vengeance. In the book the magician also becomes the counterpart to Kundrie and at the same time reflects the negative effects of Orgeluse's thirst for revenge, which are rooted in the formalities of court society. In short: Klingsor stands for all traps that a member of the court can fall into. Gawan's victory in the castle makes it clear, however, that a righteous and perfectly courtly knight (like Gawan it is) can avoid these traps. Klingsor then disappears from the book and with it all negative sides of the people.

Gawan and the magic castle of Klingsors: details and interpretation

From what has already been described above, here are the details and a final interpretation:

One morning Gawan sees Schastelmarveil lying in front of him in the brilliant sunlight. The ferryman he meets is reluctant to provide information about this magical castle. “If you really want to know, hear that you are here in Klinschor's magical land. The castle there is the magic castle. Four hundred women are held captive there by magic. There is a miracle bed in the castle that puts everyone in great need. There are many other dangers to be faced there. Knights have often tried to free the women, but none of them has ever come back alive. "

Schastelmarveil is the opposite of the Grail Castle. Just as the Grail Castle is actually not to be found on earth, but in the spiritual world, so is the Schastelmarveil magic castle. But they are different worlds: The Grail Castle represents the light world, Klingsor's magic castle represents the world of dark forces. At the point where Gawan lets the ferryman cross the river, we actually enter the supernatural world. The ferryman corresponds to the ferryman of the dead in Greek mythology. For the ferryman usually demands horses from the knights whom he translates. The horse is a symbol for the body here. Because our body is, as it were, the mount with which we move across the earth (→ secondary literature). When Gawan meets Malkreatür, Kundry's brother, before he comes to that river, this is also an indication that Gawan is now crossing the border to the supersensible world. Just as Kundrie belongs to the Grail Castle, Malkreatür belongs to Klingsor's castle. Gawan copes easily with Malkreatür, while Parzival can not deal with Kundrie . Parzival faces Kundrie helplessly and is cursed by her. Gawan, however, defeats Malkreatür and takes his horse from him. He has a clear conscience and does not need to shy away from encountering his own lower self. This is also an indication that Gawan will continue his adventures in the dark world of Klingsor. Klingsor was Duke of Capua and Naples. He seduced the wife of the king of Sicily to adultery, was castrated by that king and had to forego love for women in the future. Then he surrendered to black magic. In order to avenge himself for the shame he suffered, Klingsor wants to make as many women as possible unhappy. He ties and catches them and locks them in his Schastelmarveile castle. Gawan now wants to free these women, just as he wants to redeem the organ who lives nearby with his love. He hears from the ferryman that the day before he had set a red knight across the river, who overcame five other knights, and that he had given him their horses.

This is where the Percival part - Percival, the red knight! - and the Gawan part of the novel linked. But Percival carelessly pulls past the magic castle and only asks about the Grail.

With great concern, the ferryman now dismisses Gawan when he sets off for the magic castle. Soon Gawan is standing in front of the castle. He leaves his horse to the shopkeeper and goes through the large entrance gate. Nobody is to be seen in the castle, and so he walks through many corridors and rooms until he finally comes to a high-vaulted hall with columns, where he discovers the wonderful bed the ferryman told him about. It rolls around and whenever Gawan approaches it, it evades him. When it comes close again, he finally jumps in with sword and shield. Now a frenzied ride begins. The bed rushes from wall to wall with a roar, making the whole castle roar. Gawan covers himself with his shield and commands himself under God's protection. Through his inner calm and his trust in God, he brings the bed to a standstill.

The second threat threatens Gawan from the air. 500 throwers shower him with their projectiles, plus 500 arrows from crossbows. Despite the good shield, the hero carries wounds.

The third danger, the giant wrapped in fish skin, points out Gawan's next task: The knight kills the lion, who is now jumping in, with a stab through his chest. The four tasks represent the four elemental realms, earth, water, air and fire. Since these are bewitched and banished at Klingsor's castle by dark-demonic driving forces, they must first be purified and disenchanted by Gawan's tasks so that the 400 women can be redeemed , but the castle and the surrounding land can pass to Gawan. Gawan almost dies of his wounds and can only be healed by the women of the castle.

Parzival and Feirefiz (Book XV – XVI)

In the forest Parzival meets a pagan (Roman) knight of incomparable power - 25 countries serve him - and splendor, with a noble heart in search of honor and fame; His strength is fed from his love for his wife, the second. Parzival lives through Condwiramurs, his trusted wife, the Grail's blessing and his sons. It comes to a fight between two equals - the baptized against the Gentile, sons of the same father, strangely familiar and yet unknown to one another: two who are in truth one . Parzival smashes his sword Gahaviess on his brother's helmet - the sword that he, as a half fool, took from dead Ither and, God willed, should not be used as a corpse robbery . Here the enemy offers him peace, because he can no longer gain fame from the now unarmed man , even more, he also gets rid of his sword. Trusting the words of Parzival, Feirefiz bares his head, reveals himself to his brother: Feirefiz, black and white mixed up like a written parchment , the color of the magpie , as Eckuba described it to him. A kiss between the brothers seals their peace and Feirefiz is accepted into Arthur's round table after days of joy.

Kundrie la Surzière appears masked, the one who once cursed Parzival when he was a guest at Anfortas and did not relieve him from his suffering. Now she asks that he forgive her. Parzival overcomes his hatred and is supposed to move to Munsalvaesche to free Anfortas from his suffering by asking questions. She takes the curse from Parzival:

- Everything that is in the vicinity of the planets and what shines on their shine is intended for you to reach and acquire. Your pain must now pass. Only greedy inadequacy excludes you from the community, because the grail and the grail's power forbid you from insincere friendship. You raised concern in your youth, but the approaching joy deprived you of hope. You have won the peace of the soul and the joy of life persisted in worries.

Parzival was destined to be King of the Grail. They ride, accompanied by Feirefiz, to redeem Anfortas.

There are only two ways to free Anfortas from his suffering. His faithful keep him from letting him die, who time after time give him strength through the Grail in the hope of redemption. This is the way Anfortas Parzival can reveal: he should keep him away from the Grail. The other way is the redeeming question from the mouth of the man to whom all his joy had melted away there and to whom all worry has now passed : Uncle, what confuses you? that Anfortas heals through the power of the Lord.

Parzival sets off to the camp of his wife and children, whom he has not seen for years. As the Grail King he has almost infinite wealth, land and power. He passes on the inherited fiefs from his father to his son Kardeiß, who is then (still a child) king of these countries. With his wife and son Loherangrin, he returned to Munsal Wash on the same day.

At the Grail Castle, the Grail on Achmardisseide is carried into the ballroom by the virgin Repanse de Schoye, sister of Anfortas, where it miraculously fills all vessels with food and drinks. The colorful pagan Feirefiz cannot see the Grail, for he must not want the eyes of the pagan to gain the comradeship of those who look at the Grail without the power of baptism . Feirefiz 'attention is directed to Repanse, to which his love flares up and makes one forget the seconds. Parzival, lord of the castle and king of the grail, baptized Feirefiz if he wants to demand from Repanse Minne: he should lose Jupiter , let seconds go .

Feirefiz agrees to be baptized if he only has the girl : If it is good for me against adversity, I believe what you [the priest] command. If your love rewards me, I will gladly do God's command. He is baptized and the Grail now appears before his eyes.

After days Kundrie brings big news : death has taken seconds. Now Repanse is also really happy , the one who was without wrong before God .

Loherangrin grows up to be a strong man.

Reception history

Transfers

There are numerous translations of Wolfram's epic from Middle High German into New High German - both in verse form (especially from the 19th century) and as prose. The disadvantage of the older, rhymed transcriptions in verse form is that they inevitably had to deviate very far from the original in terms of speech and conceptual interpretation. In contrast, prose transmissions can reproduce the connotations of the Middle High German vocabulary more precisely, but at the same time defuse the original linguistic power and virtuosity of the text.

In this regard, two more recent transmissions - the prose transmission by Peter Knecht and the (inconsistent) verse transmission by Dieter Kühn (see under “Literature”) - are considered to be literarily successful and philologically correct approximations to the style and linguistic peculiarities of the original.

reception

Literary reception in German

To begin with, three works are to be mentioned as examples, which stand for adaptations of medieval material in three different epochs of German-language literature. For romance can The Parsifal (1831-32) by Friedrich de la Motte Fouque are called, for the Modern The game of questions or Journey to the sonorous Country (1989) by Peter Handke and the postmodernism The Red Knight (1993) Adolf Muschg .

Tankred Dorst brought the material to a stage play, Parzival (world premiere in 1987 at the Thalia Theater , Hamburg). A version by Lukas Bärfuss was premiered in 2010 at the Schauspielhaus Hannover .

There are also many books for young people on Parzival material and other popular forms.

In operas

When people think of “Parzival” today, one usually thinks of Parsifal by Richard Wagner (Bühnenweihfestspiel, first performed in 1882). Furthermore, Wolfram's Parzival material can be found in the children's opera Elster and Parzival by the Austrian composer Paul Hertel (world premiere in 2003 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin ).

literature

For the introduction

- Dieter Kühn : The Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach , Frankfurt a. M. 1997 ISBN 3-596-13336-X .

- (In the first half a literary journey through time to the world, work and time of Wolfram von Eschenbach, in the second half a version of Kühn's translation for the 'Library of the Middle Ages' shortened to the Parzival-Gawan storyline (see below))

- Hermann Reichert: Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, for beginners. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, 3rd, completely revised edition 2017. ISBN 978-3-7069-0915-0 .

- Introduction that deals with the most important research problems and provides a selection of key parts of the text in the original text with linguistic explanations and precise translations. Target audience: Students in the first phase of their studies and interested laypeople, while the Metzler volume Bumkes is suitable for advanced users (e.g. from: written work for a main seminar).

Text and translation / transmission

- Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. Volume 1: Text. (Middle High German text with rich readings from all manuscripts; without translation). New ed. by Hermann Reichert, based on the St. Gallen main manuscript as the main manuscript, using all manuscripts and fragments. 520 pages, Vienna, Praesens Verlag 2019. ISBN 978-3-7069-1016-3 . E-book (pdf): ISBN 978-3-7069-3008-6 .

- Hermann Reichert: Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. Volume 2: Investigations. (Studies on the textual criticism of Parzival and the language of Wolfram). 397 pages, Vienna, Praesens Verlag 2019. ISBN 978-3-7069-1017-0 . E-book (pdf): ISBN 978-3-7069-3009-3 .

- Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. Study edition, second edition. Middle High German text based on the sixth edition by Karl Lachmann , translation by Peter Knecht, with introductions to the text of the Lachmann edition and problems of the 'Parzival' interpretation by Bernd Schirok, Berlin, New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017859-1 .

- (Complete bilingual text edition with prose transmission, designed for use in the academic field, with the scientific apparatus of the Lachmann edition.)

- Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. (2 volumes), revised and commented on by Karl Lachmann's edition by Eberhard Nellmann, transferred by Dieter Kühn, (= Library of the Middle Ages, texts and translations, twenty-four volumes, edited by Walter Haug; volumes 8/1 and 8/2), Frankfurt a. M. 1994, ISBN 3-618-66083-9 .

- (Complete bilingual text edition (also after the sixth edition by Lachmann), with verse transfer when adopting the metric scheme, but renouncing rhyming. Afterword, remarks on transfer, extensive commentary, evidence of the deviations from Lachmann.)

- Wolfram von Eschenbach. Parzival. (Volume 1: Book 1–8, Volume 2: Book 9–16), Middle High German text based on the edition by Karl Lachmann, translation and afterword by Wolfgang Spiewok, (= Reclams Universalbibliothek; Volume 3681 and 3682), Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3 -15-003682-8 and ISBN 3-15-003681-X .

- (Complete bilingual text edition (based on the seventh edition by Lachmann), with prose transcription, notes and epilogue.)

- The Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach. Read and commented by Peter Wapnewski . 8 audio CDs. The HÖR Verlag DHV; Edition: abridged reading. (January 1995); ISBN 3-89584-393-8 .

Scientific secondary literature

- Joachim Bumke : Wolfram von Eschenbach. (= Metzler Collection , Volume 36), 8th, completely revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-476-18036-0 .

- (In view of the barely manageable flood of literature on Wolfram and especially on Parzival, an indispensable, fundamental orientation to Wolfram's work in general and to 'Parzival' in particular. The work offers a detailed text analysis along with an extensive bibliography of the most important secondary texts and presents the main research approaches and discussions.)

- Ulrike Draesner : Paths through narrated worlds. Intertextual references as a means of constituting meaning in Wolframs Parzival (= Mikrokosmos , Volume 36), Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1993, ISBN 3-631-45525-9 (dissertation University of Munich 1992, 494 pages).

- Bernhard Dietrich Haage: Illness and redemption in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach: Anfortas' suffering. In: Michael Fieger, Marcel Weder (ed.): Illness and dying. An interprofessional dialogue. Bern 2012, pp. 167–185.

- Paul Kunitzsch : The Arabica in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach. In: Werner Schröder (Ed.): Wolfram-Studien, II. Berlin 1974, pp. 9–35.

- Wolfram's Parzival novel in a European context , edited by Klaus Ridder, Schmidt, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-503-15532-3 , ISBN 978-3-503-15537-8 Table of contents .

- Elisabeth Martschini: Writing and writing in courtly narrative texts of the 13th century. Kiel, Solivagus-Verlag 2014, chapter Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival, pp. 31–49, pp. 291–556, ISBN 978-3-943025-14-9 .

- Hermann Reichert: Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. Volume 2: Investigations. The 'Investigations' contain, using all manuscripts and fragments, information on the principles of normalization, the reliability of each manuscript for the creation of the critical text, as well as reasons for maintaining the reading of the main manuscript or deviations from it in questionable places. 397 pages, Vienna, Praesens Verlag 2019. ISBN 978-3-7069-1017-0 .

- Werner Williams-Krapp: Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival. In: Great works of literature. Volume VIII. A lecture series at the University of Augsburg 2002/2003, edited by Hans Vilmar Geppert, francke-verlag, Tübingen 2003, pp. 23–42, ISBN 978-3-7720-8014-2 .

- (In contrast to the traditional reading and in contrast to Bumke's presentation, Williams-Krapp presents an interpretation of the novel according to which ultimately “not the Grail world, but the Arthurian world is the more human, the actually more humane” and therefore “is more exemplary for the lay reader than the obscure one Grail World ", ibid., P. 41.)

Web links

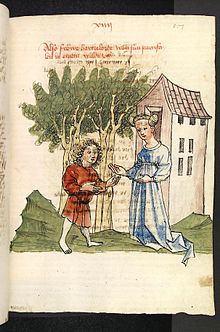

- Digitized full text of a Parzival manuscript from the Bibliotheca Palatina (Heidelberg University Library) - from the Diebold Lauber workshop in Hagenau around 1443–1446.

- (The images for this article are taken from this manuscript.)

- Digitized full text of the Parzival ('Bibliotheca Augustana') - based on the fifth edition by Karl Lachmann, Berlin 1891.

- (Since a critical edition of 'Parzival' is still a desideratum (but see the following link) - there is still no way around the "Lachmann".)

- Parzival project of the Swiss National Science Foundation at the Universities of Bern and Basel

- (The aim of the project is to achieve an electronic text edition of all manuscript variants as a prerequisite for a new critical edition of 'Parzival' - some edition samples demonstrate the possibilities of this venture. See also Parzival manuscripts and fragments of the edition samples )

- (Complete list of all Parzival manuscripts and fragments that have survived.)

- (Digital collection with approx. 84 manuscripts and fragments)

- (Complete translation in rhymed verses by Karl Simrock , 1883)

- Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzifal, Titurel and Tagelieder - BSB Cgm 19 - digitized in bavarikon

Remarks

- ^ Kindlers Literatur Lexikon, Metzler, Stuttgart 2008

- ^ Bernhard D. Haage: On "Mars or Jupiter" (789.5) in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach. In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/13, pp. 189–205, here: p. 191 f.

- ↑ See Joachim-Hermann Scharf : The names in 'Parzival' and in 'Titurel' Wolframs von Eschenbach. Berlin / New York 1982.

- ^ Bernhard Maier : Lexicon of Celtic Religion and Culture (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 466). Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-520-46601-5 , p. 265.

- ^ Friedrich Ohly : Diamond and goat blood. The history of tradition and interpretation of a natural process from antiquity to modern times. Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-503-01253-2 ; also abbreviated in: Werner Schröder (Ed.): Wolfram-Studien. 17 volumes. Schmidt, Berlin 1970-2002; Volume 3 (Schweinfurt Colloquium 1972). Berlin 1975, pp. 72-188.

- ↑ On the humoral pathological and astrological grouping of the differently dressed virgins cf. Bernhard D. Haage: On “Mars or Jupiter” (789.5) in Wolframs von Eschenbach's 'Parzival'. In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/13, pp. 189–205, here: p. 190.

- ^ Bernhard D. Haage: Studies on medicine in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach. Göppingen 1992 (= Göppinger works on German studies. Volume 565), p. 238; and: derselbe (2012/13), p. 191.

- ↑ cf. on this Bernhard Dietrich Haage: Prolegomena to Anfortas' suffering in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 3, 1985, pp. 101-126.

- ↑ Bernhard D. Haage (2012/13), p. 191.

- ↑ Bernhard D. Haage: Urjans' healing (Pz. 506,5-19) after the 'Chirurgia' of Abū l-Qāsim Ḫalaf ibn ʿAbbās az-Zahrāwī. In: Journal for German Philology. Volume 104, 1985, pp. 357-367.

- ^ Bernhard Dietrich Haage: The Thorakozentese in Wolframs von Eschenbach 'Parzival' (X, 506, 5-19). In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 2, 1984, pp. 79-99.

- ↑ Bernhard D. Haage: Methodical for the interpretation of Urjans' healing (Pz. 505,21-506,19). In: Journal for German Philology. Volume 111, 1992, pp. 387-392.

- ↑ cf. for example Bernhard Dietrich Haage: Studies on medicine in Wolframs von Eschenbach's “Parzival”. , Kümmerle, Göppingen 1992 (= Göppinger works on German studies, 565), ISBN 3-87452-806-5

- ↑ Bernhard D. Haage (2012/13), pp. 197–203.

- ↑ See on this Paul Kunitzsch : The planet names in the 'Parzival'. In: Journal for the German language. Volume 25, 1969, pp. 169-174; also in: Friedhelm Debus , Wilfried Seibicke (Ed.): Germanistische Linguistik 131-133 (= Reader zur onenology III, 2 - toponymy ). Pp. 987-994.

- ↑ See Bernhard D. Haage: On “Mars or Jupiter” (789.5) in Wolframs von Eschenbach's 'Parzival'. In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/13, pp. 189-205.

- ^ First printing: Friedrich de la Motte-Fouqué: Der Parcival , edited by Tilman Spreckelsen, Peter-Henning-Haischer, Frank Rainer Max, Ursula Rautenberg (selected dramas and epics 6). Hildesheim et al. 1997.

- ↑ Peter Handke: The game of questions or the journey to the sonorous land. Frankfurt a. M. 1989, ISBN 3-518-40151-3

- ^ Adolf Muschg: The Red Knight , Frankfurt a. M. 2002, ISBN 3-518-39920-9 .