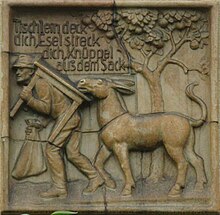

Set the table, donkey and club out of the sack

Little table set yourself, gold donkey and stick out of the sack ( Little table, set yourself up! ) Is a fairy tale ( ATU 212, 2015, 563). It is in the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm at position 36 (KHM 36). In the first edition it was called Von den Tischgen deck dich, the gold donkey and the club in the sack , in the second table deck dich, gold donkey and club out of the sack , in all the other tables deck you, gold donkey, and club out of the sack . Ludwig Bechstein took it over in his German fairy tale book as a little table deck you, donkey stretch you, stick out of the sack (1845 No. 41, 1853 No. 38).

content

A tailor lives with his three sons and a goat, who feeds them with their milk, for which she has to go to the pasture every day and eat the very best herbs. When the eldest has grazed her nicely and asks whether she is full, she replies: “I'm so full, I don't like a leaf: muh! muh! ”But when the father asks the goat at home, she replies with a lie:“ What should I be fed up with? I just jumped over Gräbelein, and found not a single Blättelein: muh! muh! ”The father does not recognize the goat's deception and in an affect chases the elder out of the house with his yard . The other two sons feel the same way over the next few days. When the father takes the goat out himself and she answers that way outside and at home, he realizes that he has done his sons injustice, shears the goat's head and chases them away with the whip.

The sons do an apprenticeship with a carpenter, a miller and a turner. At the end of the day the eldest gets an inconspicuous little table; if you say “little table, set yourself up!”, then it is neatly laid and the most delicious dishes are served. The middle one gets a donkey; if you say “Bricklebrit!” to it, pieces of gold fall out at the front and back. All three sons finally forgive their father during their wandering years and see the possibility that their father will forget his resentment as soon as they have won it with their own miracle. Before they return home, however, the two older ones are betrayed in their generosity one after the other by the same landlord when the one slips a false table and the other another donkey. They only notice it when they want to show off their marvelous thing at home. You are ashamed of all the guests invited by your father, who now has to continue working as a tailor.

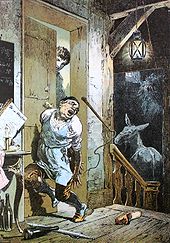

The youngest, warned by his two brothers, gets a stick in the sack from his master , which knocks out every opponent when you say “stick out of the sack!” And only stop when you say “stick in the sack!”. With that he takes the little table and the donkey from the landlord when he tries to steal the sack - used as a pillow - whose value he had previously praised.

Out of shame, the goat crawls over its bald head in a burrow, where the fox and then the bear are frightened by their glowing eyes. But the bee stings her shaved head, so that the goat flees from pain and, now finally homeless, is lost.

origin

Grimm's entry in the hand copy attributes the Schwankmärchen Johanna Isabella Hassenpflug , she claims to have heard it from "an old Mamsell Storch at Henschel". According to the findings of a Grimm researcher at the University of Kassel , the Mamsell was Eleonore Storch, a factory owner's daughter from Rinteln and sister-in-law of the Kassel entrepreneur Georg Christian Carl Henschel . A second, shorter text version was reproduced in the first print; it later appeared in the annotation as “other story” (by Henriette Dorothea Wild ).

Grimm's note noted “From Hessen” (by Jeanette Hassenpflug ). “Another story” (1811 by Dortchen Wild ) begins with the father sending the sons to wander one after the other with pancakes and pancakes. They guard the herd of a rich master in a nutshell, but allow themselves to be forbidden to be lured into a house by dance music (cf. KHM 57 ). Table linen and donkey are swapped on the way, only the youngest plug their ears with cotton. He brings back the miraculous things with the stick. The father is happy not to have wasted his three pennies on them. You mention Lina's book of fairy tales by Albr. Lud. Grimm No. 4 “the stick out of the sack”, Zingerle's fairy tale from Merano “S. 84 and 185 ", Swabian at Meier No. 22, Danish at Etlar " S. 150 ", in Norwegian by Asbjörnsen " S. 43 ”, in Dutch in Johann Wilhelm Wolf's Wodana No. 5, in Hungarian in Stier “ S. 79 ", in Polish by Levestam " S. 105 ", Wallachian at Schott No. 20," from the Zillerthal "at Zingerle " S. 56 “, The bottle in Grimm's Irish fairy tale , in Russian at Dietrich No. 8, KHM 54 The satchel, the hat and the horn . Not mentioned, but strikingly similar and now certainly known to the Brothers Grimm is from Giambattista Basile's Pentameron I, 1 Das Märchen vom Orco .

language

The plot always remained the same, but the text was linguistically embellished. The first edition says that all good things come in threes. From the 2nd edition onwards, the tailor (previously: Schuster) means that one wants to "make a fool of him". With “Boiled and Roasted” (from 2nd edition) the boy is “in good spirits” (from 2nd edition). Incidentally, there are more and more paraphrases for beating, which Wilhelm Grimm apparently added afterwards and with tailor's props: He “tanned the poor boy's back with the cubit” (from 4th edition), the club “patted the skirt or doublet on the back off ”,“ rubbed the seams ”(from 2nd edition onwards). The bear is "not at ease in his skin" (from 3rd edition). The "I want grace for justice" (from 3rd edition, later also KHM 12 , 192 ) is literary common and is similar in Eisenhart's principles of German rights in proverbs . Further phrases from the 2nd edition are: The little table offered “what his heart desires”, the donkey owner “the best is good enough, and the more expensive the better”, then it remains “as empty as another table that doesn't speak the language understands ”and“ it turned out that the animal understood nothing about art, because not every donkey gets it that far ”(similar to the 2nd edition). The landlord screams and the stick beats him to the beat (from 2nd edition; see Basiles Das Märchen vom Orco ). From the 3rd edition onwards, the narrator says last at the gold donkey: "I'll see you, you would have liked to have been there too."

Fairy tale research

According to Jurjen van der Kooi , ATU 563 is first found in Basile's Das Märchen vom Orco , but it seems to be older. Thanks to Grimms and Bechstein's version, it is widespread with three brothers especially in Europe, but also in Japan, America and South Africa. Props vary geographically and culturally, outside Europe sometimes two or four magic gifts and often animals as actors. The opening episode varies a lot, especially when linked to ATU 564, mostly with a rich brother who sends the poor one to the devil who gives him magic gifts. The connection with malicious goat (ATU 212) only occurs in Grimm and otherwise only in a few German, Flemish and West Indian variants. ATU 563 is often combined with ATU 569 ( the satchel, the hat and the horn ). Motive analogies exist to other magical tales from ATU 560 - 649. In variants, the gifts are compensation of the frost for destroyed harvest, or the wind has scattered the flour. A poor man wants to beat up God and receives the gift, or his bean grows up to heaven where he receives it. In the Islamic world, a lumberjack receives magical gifts from the tree so that he can spare the trees, or from the well into which a pea fell, or from spirits who think he wants to eat them. In India, a jackal gives away a magical cow and brings it back when it is stolen.

interpretation

Jurjen van der Kooi sees the universal attraction of fairy tales, which condenses the wishes of poor people into concrete scenes of abundance and punishes sacrilege (wishful poetry). Psychological interpretations were not convincing, they often only took into account one version or one motive, such as the stick ( phallic symbol ). According to Walter Scherf , in the magic fairy tale the listener can witness the hero's exodus and self-discovery, whereas fluctuating mixed forms aimed at drastic behavioral instruction. If there are only two gifts, often the donkey is missing, one ensures child-like, carefree “ability to buy” the other for self-assertion: “It is not enough to have a table that is always set or to pay for everything your heart desires can. These are life plans behind which the escape into childhood is hidden. ” Ottokar Graf Wittgenstein already interpreted the gifts as oral, anal and phallic child development phases . Wilhelm Salber sees on the one hand a greed for conflict-free unity in unhistorical at the same time, but also action with change and development. The all-desirable becomes the real. The homeopath Martin Bomhardt compares the fairy tale with the drug picture of Lycopodium clavatum .

Receptions, parodies and language use

In Eichendorff's good-for-nothing it says: "I was only allowed to say: 'Little table, set yourself up!', Wonderful things were already there ...". Note also the introductory poem Knüppel aus dem Sack in Hoffmann von Fallersleben's Nonpolitical Songs ("... O fairy tales, would you come true / only one day a year ...").

Ludwig Bechstein took over the fairy tale without the goat episode as a table set yourself, donkey stretch yourself, stick out of the sack in his German fairy tale book . The tall, the fat and the stupid, as a carpenter, miller and turner, all find the same master in the forest house who is “versed in all subjects” and gives them the things. Bechstein notes “Oral”, he followed Grimm's version.

Josef Sills ironically reports a legal follow-up to official German, with the youngest being accused of bodily harm, the teachers for not paying health insurance contributions and the table and donkey owners for the unauthorized production of luxury goods and offenses against the foreign exchange and value date law. Iring Fetscher , ironically naming Marxist colleagues, interprets the three gifts as feudalism , capitalism and revolutionary people's war or as a technological, economic and political aspect of the bourgeois revolution.

The fairy tale is often known under the shortened and slightly changed title: “Tischlein, deck dich!” In this form, it is used to name food delivery services, restaurants and table decorations. The sayings like “I'm so full, I don't like leaves” are particularly well-known . The term gold donkey is used in a figurative sense for procedures that promise a high economic profit, comparable to the term cash cow . The saying “He has a cash cow at home” (or, based on the fairy tale coarse: a money shit) is used for people who spend money “with full hands”.

theatre

- Little table, cover yourself, - donkey, stretch yourself, - club, out of the sack! A children's fairy tale game in 3 pictures by Robert Bürkner .

- The Augsburger Puppenkiste and other puppet theaters already had it in their program.

Movies

- 1921: Little table set yourself, little donkey stretch yourself, stick out of the sack , silent film , 64 min (director: Wilhelm Prager ), Germany

- 1938: Little table set yourself, donkey stretch, stick out of the sack , 79 min (director: Alfred Stöger ), Germany

- 1956: Tischlein deck dich , 79 min (Director: Fritz Genschow ), Germany

- 1956: Tischlein deck dich , 72 min (Director: Jürgen von Alten ), Germany

- 1966: Tischlein, set dich ... (Direction: Gisela Schwartz-Martell ), DEFA

- 1970: Tischlein deck dich , puppet cartoon, 33 min (director: Rudolf Schraps), DEFA

- 2004: SimsalaGrimm , German cartoon series 1999, season 2, episode 3: Tischlein deck dich

- 2006: Tischlein deck dich - donkeys, goats, real men , comedy from the 2nd season of the Pro Sieben / ORF series Die Märchenstunde , Germany / Austria

- 2008: Tischlein deck dich , fairy tale film from the 1st season of the ARD series Six in One Stroke , Germany (Director: Ulrich König )

literature

- Brothers Grimm: Children's and Household Tales . Complete edition. With 184 illustrations by contemporary artists and an afterword by Heinz Rölleke . Pp. 215-228. , 19th edition, Artemis & Winkler / Patmos, Düsseldorf / Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-538-06943-3 .

- Brothers Grimm: Children's and Household Tales . Last hand edition with the original notes by the Brothers Grimm. With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin, not published in all editions, published by Heinz Rölleke. Volume 3: Original Notes, Guarantees of Origin, Afterword. Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, pp. 77-78, p. 457, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 .

- Hans-Jörg Uther: Handbook to the children's and house fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm . de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, pp. 88-92, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 .

Web links

- Märchen.com: Bechstein's little table set you up, donkey stretch out, clubs out of the sack , 1847

- Interpretation by Daniela Tax on Tischlein deck dich

- Illustrations for “Tischlein deck dich” by Ludwig Richter, Georg Mühlberg and Paul Hey

- Illustrations

Individual evidence

- ↑ Grimms "Tischleindeckdich": Kassel Germanist identifies the narrator as the daughter of a manufacturer, press release of the University of Kassel from January 3, 2018. http://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/universitaet/pressekommunikation/neues-vom-campus/meldung/article /grimms-tischleindeckdich-kasseler-germanist-identified-erzaehlerin-als-fabrikantentäure.html

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Uther: Handbook on the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 88-92.

- ↑ Lothar Bluhm and Heinz Rölleke: “Popular speeches that I always listen to”. Fairy tale - proverb - saying. On the folk-poetic design of children's and house fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. New edition. S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-7776-0733-9 , pp. 72-74.

- ↑ Jurjen van der Kooi: table linen. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 13. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023767-2 , pp. 676-682.

- ↑ Jurjen van der Kooi: table linen. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 13. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023767-2 , pp. 676-682.

- ↑ Walter Scherf: The fairy tale dictionary. Volume 2. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 978-3-406-51995-6 , pp. 1198-1201.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Uther: Handbook on the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 88-92.

- ^ Wilhelm Salber: fairy tale analysis (= work edition Wilhelm Salber. Volume 12). 2nd Edition. Bouvier, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02899-6 , pp. 99-100, 138

- ^ Martin Bomhardt: Symbolic Materia Medica. 3. Edition. Verlag Homeopathie + Symbol, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-9804662-3-X , p. 815.

- ↑ Lothar Bluhm and Heinz Rölleke: “Popular speeches that I always listen to”. Fairy tale - proverb - saying. On the folk-poetic design of children's and house fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. New edition. S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-7776-0733-9 , p. 72.

- ↑ Steffen Martus: The Brothers Grimm. A biography. 1st edition. Rowohlt, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-87134-568-5 , p. 396.

- ^ Hans-Jörg Uther (Ed.): Ludwig Bechstein. Storybook. After the edition of 1857, text-critically revised and indexed. Diederichs, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-424-01372-2 , pp. 179-186, 387.

- ↑ Josef R. Sills: Set the table, donkey stretch. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 166–169 (first published in: Simplicissimus. No. 32, August 5, 1961, pp. 501–502 .; author's information “Josef R . Sills "with"? "At bodice.).

- ↑ Iring Fetscher: Who kissed Sleeping Beauty awake? The fairy tale confusion book. Hamburg and Düsseldorf 1974, Claassen Verlag, pp. 66-69, ISBN 3-596-21446-7 .