Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (born March 19, 1905 in Mannheim ; † September 1, 1981 in London ) was a German architect and authoritative for architecture under National Socialism . He was also an armaments organizer during the Nazi era and from 1942 Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition . He was sentenced to 20 years in prison as a war criminal in the Nuremberg Trial .

Speer made an extraordinary career from 1933 onwards due to his ambition. Later he became a favorite of Hitler - especially as an architect - and he wanted to be close to him as often as possible. From 1937 he was general building inspector for the Reich capital, planned the new building in Berlin and managed numerous monumental building projects by Hitler, including the construction of the New Reich Chancellery , which were intended to underline the Nazi claim to rule. When Fritz Todt died in a plane crash on February 8, 1942, Speer succeeded him as Minister of Armaments. Despite heavy bombing, he succeeded in increasing total production every year until the end of the war . In this way he made a decisive contribution to the prolongation of the German warfare, which led to the largest number of victims in the last year of the war. As Minister of Armaments , he was jointly responsible for the employment of seven million forced laborers , including around 450,000 concentration camp prisoners, and influenced the operation and expansion of concentration camps . Speer was one of the 24 accused in the Nuremberg trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Tribunal , who was not aware of important parts of Speer's activities. In 1946 he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 20 years in prison. He served them completely in the Spandau war crimes prison .

In particular because of his strongly embellished, autobiographical writings published after his imprisonment and the justification of his worldview contained therein, his participation in the construction of concentration and mass extermination camps , as one of the main perpetrators of the National Socialist war crimes and because of the enrichment in Jewish emergency sales (" Aryanization ") ), Speer is generally not found to be trustworthy as a contemporary witness .

Live and act

Youth and education

Speer came from a bourgeois family in Mannheim. His father Albert Friedrich Speer and his grandfather were architects. His older brother was called Hermann (* 1902; † 1980), his younger Ernst (* 1906, missing in Stalingrad in 1943 ). In Mannheim he attended a private school between 1911 and 1918 and then the Realschule branch of the Lessing School, a Realgymnasium with Realschule (today Lessing-Gymnasium). After the family moved to Heidelberg in 1918, he attended the upper secondary school there, today's Helmholtz grammar school . At the insistence of his father, he studied architecture, first at the University of Karlsruhe and from spring 1924 to summer 1925 at the Technical University of Munich . In the fall of 1925 Speer moved to the Technical University of Berlin . After trying in vain to be accepted into Hans Poelzig 's seminar , he began studying with Heinrich Tessenow in 1926 . After graduating in 1927, Speer became his assistant and remained so until the beginning of 1932.

Turning to National Socialism

During this time, political rallies took place almost daily in the atrium of the university. The college itself was a National Socialist stronghold . In Speer's department, around two thirds of the students chose “brown”.

Speer's turn to National Socialism was of his own accord. Every step of his commitment to Hitler's rule, against Jews, political opponents and minorities, was determined and zealous. Like his father, he deliberately did not want to build rental and private houses, commercial buildings, villas or occasionally even public buildings. He could have done this without any problems, because as the son of wealthy parents he was financially independent. Right from the start, this set him apart from most members of the established Nazi functional elite, who often developed their Nazi convictions with the desire for security of supply for family members.

Speer claimed in his memoirs after the war that his interest in National Socialism arose in December 1930. His students had taken him to a hall on the Hasenheide to a Hitler rally in front of Berlin professors and students. He heard a "speech without a roar". He later claimed that "the magic of the voice" had not released him. Speer had already become a member of a National Socialist organization in April 1930, the National Socialist Automobile Corps (NSAK), which later became part of the NSKK . In the fall of 1930 Speer received the first building contract from a National Socialist organization. The head of the NS- Kreisleitung West in Berlin, Karl Hanke , commissioned him to convert a rented villa in Berlin-Grunewald into a party office free of charge. In January 1931 Speer joined the NSDAP ( membership number 474,481). In the same year he became a member of the SA , but switched from the SA to the Motor-SS in 1932 .

Shortly before the Reichstag elections on July 31, 1932 , Speer received the order from Joseph Goebbels to convert the new Gauhaus at Vossstrasse 10 , which the party had just acquired, for party purposes. His design corresponded to the need for representation of the fast growing party. Goebbels was "enthusiastic". Then Speer left Berlin for lack of orders and went back to Mannheim, where he settled as an architect. Here too, however, he received no orders.

After the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , Hitler appointed Joseph Goebbels as Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda . Goebbels received the previous building of the government press office, the Leopold-Palais on Wilhelmplatz (opposite the Reich Chancellery - a classicist building from the 18th century, which was later converted by Schinkel ) as the seat of his ministry. Again an architect was sought who could design it in terms of interior design. Hanke again sent the order to Speer and brought him back to Berlin from Mannheim for this purpose. Speer himself wrote that he had the building rebuilt in the manner desired by Hitler and Goebbels without paying much attention to the historical fabric of the building.

A little later, Goebbels commissioned him to prepare the parade grounds on Tempelhofer Feld for one of the first Nazi mass parades on May 1, 1933 (“ National Labor Day ”). Speer had six large swastika flags and three flags with the imperial colors black, white and red hung behind a large speaker's platform (with space for the entire party leadership). This made him the set designer for the large-scale marches in the Nazi state. Goebbels soon commissioned Speer, who was recognized as loyal to the line, to modernize the interior design of his own official apartment on Königgrätzer Strasse (today Ebertstrasse ) south of the Brandenburg Gate . Goebbels was satisfied with this and now suggested Speer as the architectural designer for the planned Nazi party rally in Nuremberg. Speer's suggestions appealed to Hitler. Hitler's personal architect at the time, Paul Ludwig Troost from Munich, was commissioned to convert the Reich Chancellor's official apartment in the Old Reich Chancellery , but Speer was the site manager . Troost died in January 1934 and Speer took over his duties.

Hitler's architect

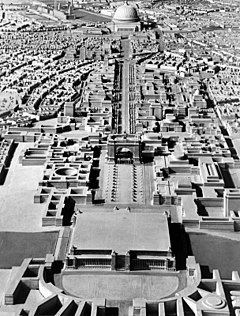

From 1934/1935 Speer designed monumental buildings for the party rallies of the NSDAP in Nuremberg ; these were only partially realized due to the war. From 1935 he was involved in the initially secret planning of the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin, which began in 1934 . After extensive, preparatory demolition work in the following two years, construction work began in 1937, which, including all other expansion measures, continued into the 1940s. Appointed General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital (GBI) on January 30, 1937, a newly created authority with an office in Palais Arnim was available to him; In this function Speer was directly subordinate to Hitler. His main task was the rebuilding of Berlin. For this purpose, the Great Hall north of the Reichstag building was to be built in the Spreebogen as the largest domed building in the world , which was to be connected via the "north-south axis" with a new "Südbahnhof" at the site of today's Südkreuz station in Berlin-Tempelhof . From 1938, buildings in the Spreebogen and Berlin-Tempelhof were demolished for this purpose. Although more than 100,000 apartments were missing in Berlin, the GBI's plans envisaged demolishing a total of 52,144 apartments in Berlin for the redesign. In 1936 Hitler awarded his favorite architect the title of professor.

Speer himself was the first to propose “compulsory hiring of Jews” in an internal meeting on September 14, 1938. He announced that he would clarify this proposal with Hitler. “Speer pursued an anti-Semitic policy on his own initiative, as it seemed normal to him.” Since Hitler agreed, rental contracts of Jewish tenants, evictions and confinements in Jewish houses as well as the Aryanization of Jewish property on the basis of the ordinance on the Use of Jewish assets . In this way, an estimated 15,000 to 18,000 apartments were “requisitioned” in the following months.

After the beginning of the war in September 1939 Speer ordered a general stop of the demolition of the apartment; Jewish tenants and owners continued to be evicted from their apartments.

The lists drawn up by the Speers organization for the evacuation of the Berlin apartments of Jews formed the basis for the later deportations of Berlin Jews to Riga in September and October 1941 . A final report said that a total of 75,000 Jewish people had been "resettled" to various locations.

Speer's authority was significantly involved in the planning, approval and construction of the around 1,000 known forced labor camps in and around Berlin - their actual number is now estimated at over 3,000 - and operated several of them under their own control. After Siemens and the Reichsbahn , the GBI was the third largest operator of such warehouses in the Berlin area in 1942/43. According to the plan of the GBI from 1940, the deployment of forced laborers and prisoners of war was to increase to over 180,000 people after the war.

Speer agreed with Heinrich Himmler that the concentration camp inmates would manufacture and deliver building materials . The capital for the company " Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DEST)" founded by the SS was financed from Speer's budget. The money flowed directly into the construction of the concentration camp system. The interest-free loan for the SS-Totenkopfverband was repayable to Speer's authority in the form of stones. That is why almost all concentration camps between 1937 and 1942 were built near clay pits or quarries . After the occupation of France in June 1940, the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp was built in the Vosges at Speer's suggestion to break the red granite found there. In 1940 Speer himself determined the location of the Groß-Rosen concentration camp in Silesia near the granite deposits there.

Files and documents available today prove that the deportation lists were drawn up between October 1941 and March 1943 by Speer's employees together with the Gestapo . Speer denied knowledge of this until his death. Nevertheless, he wrote in a letter of December 13, 1941 to Martin Bormann that the “action was in full swing” and complained that Bormann wanted to provide “Jewish apartments” to bombed Berliners, although he (Speer) was entitled to them.

In September 1941 Speer became a member of the Reichstag as the successor to the late " old fighter " of the NSDAP, Hermann Kriebel .

Urban development plans for the “Third Reich” and reconstruction

In addition to Speer, the architects Paul Ludwig Troost (1878–1934), Roderich Fick (1886–1955) and Hermann Giesler (1898–1987) worked more closely and intensively with Hitler than any other master builder of National Socialism. The latter entrusted them with the planning and also in some cases the execution of his most important representative building projects, which enabled them to exercise a decisive cultural-political influence in the Nazi state between 1933 and 1945 thanks to their position as a 'leader'.

In the early days of the regime, Albert Speer was able to prevail over Paul Schultze-Naumburg and his homeland security architecture with neoclassical concepts. Speer became the leading Nazi architect in close cooperation with his client, Adolf Hitler. This provided the basic programmatic line for far-reaching urban development changes. For example, Hamburg was to be rebuilt as the “city of foreign trade”, Munich as the “ capital of movement ”, Nuremberg as the “city of Nazi party rallies ” and Linz , where Hitler wanted to be buried, as the “ Führer city of Linz ”. In 1937, Hitler gave Speer the biggest order to present plans for the redevelopment of Berlin , which should become a cosmopolitan city: "We have to trump Paris and Vienna".

As early as 1940/1941, a large number of specialist publications had been submitted for reconstruction. From 1943 Speer set up a central “ Working Staff for the Reconstruction of Bombed Cities ” under his leadership. The architects represented here and their planning and structural considerations - with the exception of Speer himself - played an important role for decades after the end of the war. Their modernist plans came to fruition almost without exception, dispensing with Nazi symbolism, with exceptions such as B. the inner cities of Münster and Freudenstadt .

Armaments Minister 1942 to 1945

A few hours after the armaments minister Fritz Todt's fatal plane crash (February 1942), Hitler surprisingly appointed Speer as his successor in all offices, i.e. Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition , Head of the Todt Organization and General Inspector for German Roads, Inspector General for Fortifications and General Inspector for Water and Energy . However, he had already successfully organized major logistical projects and other tasks for the military, such as the construction of submarine bunkers and the maintenance of the infrastructure in Ukraine. He remained unchanged as General Building Inspector for the Reich capital . Speer thus belonged to the closest leadership of the Third Reich. He was responsible for the entire army armament and for all types of ammunition, but initially not for the navy and air force.

Speer managed to reorganize the cumbersome process of arms production in a short time. He withdrew this largely from the Wehrmacht and shifted it to industry. A three-dimensional organization was used for this:

- “Committees” were responsible for awarding contracts, for example for ammunition, weapons, tanks. These had already been set up by Todt, Speer added more.

- "Rings" were responsible for the overall supply of important supplies, e. B. Ball bearings and forgings.

- "Commissions" took over the constructions, for example of tanks, guns, motor vehicles.

All of these organizations were filled with high-level industry representatives. Speer called this system the "great self-governing body of the arms industry ".

A lack of transparency in the distribution of raw materials, especially with the ever scarce steel, was a major weakness of the previous system. This was remedied by a newly established “Central Planning”, headed by Hans Kehrl . In addition to Speer, General Luftzeugmeister Erhard Milch took part in their meetings and, depending on the topic, other people primarily responsible such as Fritz Sauckel, the general representative for work, or representatives from administration and industry. This body ensured that the production programs remained feasible: in terms of raw materials and manpower. According to Tooze, it was “the real war cabinet of German business”.

Speer was able to show successes quickly, even if these were initially hardly attributable to his own term of office. After the defeat of the Wehrmacht in front of Moscow , this was a very welcome topic for Nazi propaganda . Speer's new organization proved its worth and enabled considerable rationalization and material savings. Speer organized the essential logistical support for the war of conquest and extermination in the east, which was particularly emphasized in the journal Signal . By the autumn of 1944, armaments production increased in what was perceived to be astonishing, despite the destruction caused by Allied bombing. Later one spoke in part of an armaments miracle . Again and again Hitler rewarded this with praise. Of course, the German armaments lagged far behind that of the Allies, which Speer knew, but Hitler rejected or did not want to admit. It was not until 2006 that the historians Scherner and Streb were able to prove more precisely that the alleged armaments miracle was another myth of Albert Speer. The myth was promoted by the publication of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), which examined the effects of the Allied bombing on the German economy after the war. The scientists of the USSBS took over the figures from Speer's Ministry without checking and came to the same conclusion. For the first time, Scherner and Streb compared, among other things, the increase in armaments productivity in Speer's sphere of control (army armor) with areas that Speer was not subject to (air armament). The comparison showed that air force and army armament production increased at the same rate. However, the air armament came into the Speers area of control only from early summer 1944. The factual influence of Speer on the increase in arms production was therefore a myth. In fact, it was Speer himself who first coined the term when, on June 9, 1944, in front of representatives of the Rhenish-Westphalian industry, he stylized his achievements as a “miracle of armament” - a term that was immediately spread by the mass media. In his lectures he mostly operated with percentage rates of increase. In his diagrams, however, he defined the corresponding production units, i.e. tanks, rifles or ammunition, imprecisely and sometimes manipulatively. For example, he ordered that the extender should also be part of the explosives. When it comes to certain explosives production - if you look closely - fifty percent filler is required, which led him to announce an alleged increase in production.

Speer was able to expand his sphere of influence considerably: in July 1943, naval armaments were added. In September he took over essential functions of the Reich Ministry of Economics. He was thus also responsible for the most important areas of the civil economy - now his title was "Reich Minister for Armaments and War Production". Finally, in 1944, he also took over the air armaments.

The labor force was a major bottleneck for the defense industry. Almost half of the men employed in the German economy were drafted into the Wehrmacht during the war. In order to maintain arms production, trade, handicrafts and the consumer goods industry were severely thinned out and more women were hired. However, this was not enough. Rather, men and women from the occupied territories were brought in, initially voluntarily, then under duress. There were also prisoners of war, Jews and other concentration camp inmates. At the end of the war this was more than 7 million, about 20% of all employees. Speer later referred to the fact that it was not he, but Fritz Sauckel , the general representative for work , who was responsible for the procurement of the workers he had requested.

Speer knew that in the first months after the attack on the Soviet Union, the Soviet prisoners of war in German hands were barely fed. Therefore, shortly after taking office, he demanded that the foreigners working in Germany be adequately fed. He was able to achieve this for the forced laborers from western countries, but less so for those from the east and for the prisoners of war. Those from Poland and the Soviet Union fared worst. The survival rate of Soviet prisoners of war in Germany was only 42%. A total of around 2.7 million of the foreigners, Jews and concentration camp prisoners working for the Reich perished. However, that was not in Speer's interest: manpower was a scarce commodity for him and should be retained if possible.

In 1942, numerous Jews were employed in the Berlin armaments factories. In accordance with his view that workers for the production of weapons must have absolute priority, Speer endeavored to ensure that these Jews were not initially deported to the extermination camps, against Goebbels' bitter resistance. He declared that they were indispensable for arms production. It was not until early 1943, after the defeat at Stalingrad , that Goebbels was able to assert himself with Hitler. In autumn 1942 Speer agreed with the head of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office, Oswald Pohl , to use 50,000 Jews intended for deportation in the armaments industry. This did not happen because Hitler preferred to have forced laborers brought in. If Speer could use Jews for arms production, however, then he took it. Contrary to what he later claimed, he was aware of the extermination of the Jews . He generally admitted these and other Nazi crimes and thereby pursued his goals. In September 1942 Speer discussed the enlargement of Auschwitz with Oswald Pohl and provided a construction volume of 13.7 million Reichsmarks. In a building file based on discussions between Speer, Pohl and the construction manager of the SS, Hans Kammler , the “cost estimates” for “ special treatment ” with the “rail connection” for the ramp, the new crematoria and other measures are recorded. After the negotiations were concluded, Head of Office Kammler emphasized the “extraordinarily large construction volume” of the construction project, which he called “Prof. Speer's special program”.

According to the historian Magnus Brechtken, Speer saw forced laborers as a mere "weapon of war" which are essential to maintain arms production. In Nuremberg Speer stated that in 1943/44 almost half of the workforce deployed for war purposes was under his responsibility. Almost half a million of the foreign workers without prisoners of war were killed between 1939 and 1945. At the same time, the armament efforts led by Speer prolonged the war, with the greatest number of war deaths in the last year of the war, especially among the German civilian population. The historian Heinrich August Winkler sums up Speer's actions in the context of foreign workers, also taking advantage of the “labor Jews”: “Under his aegis, not only was German industry more strictly subjected to the requirements of the war economy than before, Speer also directed [...] the army of foreign workers Foreign civilian workers, concentration camp prisoners, Soviet and other prisoners of war as well as 'labor Jews' whom he ruthlessly used, and in extreme cases that meant up to physical extermination through work, to increase German arms production. "

Inconsistent behavior in the face of defeat

Speer's actions in the final year of the war are contradictory. On the one hand, he recognized the impending defeat: the systematic and repeated destruction of German fuel production from May 1944 threatened the final paralysis of the Wehrmacht. Speer relentlessly explained this to Hitler in a series of "hydration memoirs". He also criticized Hitler's decisions to use the fighter planes primarily at the front instead of to protect basic industries. Further memoranda from late 1944 announced the imminent collapse of the entire arms industry to Hitler. Hitler let Speer get away with this while suppressing otherwise (even tentative) indications of defeat.

When he fell seriously ill at the beginning of 1944, this would have been a good opportunity to retreat inconspicuously in view of the war that was already recognizably lost. But he did the opposite, because above all with the Nazi greats Himmler and Goebbels he was one of the driving forces behind the totalization of the war, which resulted in millions more deaths. In a conspicuous way, Hitler is too lethargic in the perception of the three, and the murderous final phase from the summer of 1944 is organized by the trio to which he belonged. Speer wanted to mobilize the last of his forces for armaments. In a memorandum “Total War” from July 1944, he called for radical measures: The administration should be simplified to the bare minimum, the number of domestic workers should be reduced, and the lower services of the Wehrmacht could also surrender forces. The study of humanities subjects is now unnecessary, restaurants and entertainment venues are superfluous. However, this was hardly implemented. In a series of speeches between May and December 1944 he also called for efforts to be increased to the utmost. During the second half of 1944 he had violent arguments with Joseph Goebbels : While Speer wanted to increase armaments production, Goebbels tried to deprive him of the workers in order to bring them to the Wehrmacht. Hitler did not take Goebbels' side, but left both of them to their conflict without intervening. In any case, Goebbels only partially achieved his goals and - unlike Speer wrote it in his "Memoirs" - Goebbels could by no means give him orders. Nevertheless, after July 20, 1944, as the "Commissioner for Total War", he gained more influence than Speer, since in the final phase of the war soldiers were temporarily more important than arming them with new armaments.

Even before the “ Auschwitz concentration camp was closed ”, Speer's insistence that the SS had able-bodied Jews marched to Germany for armaments work, including to Dachau and the Dora-Mittelbau tunnels in the Harz Mountains, where they were assisted by the Todt Organization under murderous working conditions the production of V-2 missiles were used.

When they withdrew, the Wehrmacht was supposed to thoroughly destroy industry and infrastructure. However, there was usually not enough time for this scorched earth policy and / or the Germans had too few resources for it and / or local troops did not carry out the draconian orders (for the latter see, for example, 'Trümmerfeldbefehl' Paris 1944 ). When the fronts approached the Reich borders in autumn 1944, Speer reached out to Hitler that industrial plants should not be destroyed, but only temporarily "paralyzed", on the grounds that they could probably be recaptured. Armaments could then continue to be produced until the end.

On March 19, 1945 - US troops had already crossed the Rhine and the Red Army had crossed the Oder - Hitler lifted the regulations on paralysis and ordered the ruthless destruction of industry, infrastructure and property: the so-called Nero order . Eleven days later Speer was at least partially able to change Hitler's mind: the industry was paralyzed again, bridges should only be destroyed if it was military necessity. It is difficult to assess what kind of destruction Speer actually prevented. When the start of the Allied offensive from the bridgeheads on the Rhine was imminent in mid-March 1945 and the Red Army was preparing for the Battle of Berlin on the Oder , Speer proposed in a memorandum to Hitler that all Wehrmacht units and the Volkssturm should be concentrated on the Rhine and Oder: " Perseverance on the current front for a few weeks can win respect for the enemy and perhaps still favorably determine the end of the war ”.

In reporting to Hitler, Speer was ousted by his deputy, Karl Saur , from late 1944 onwards. Hitler named him as Speer's successor in his Political Testament of April 29, 1945. Speer did not oppose this. His priorities had shifted: on January 27, 1945, he had already given a retrospective review in an “accountability report” to employees and industry and no longer prompted further efforts. Rather, it was now about future tasks in a time after the Third Reich. In March 1945, agricultural machinery and food should have priority over armaments. Because otherwise Germany's survival was not possible. In a post-Hitler Germany, he expected a post in the reconstruction work for himself . At that time it never occurred to him that he could be morally compromised.

Speer was in Hamburg towards the end of the war; but on April 23rd he flew to Berlin again to say goodbye to Hitler and Eva Braun , where he witnessed Hermann Göring's dismissal . On April 24th he met for the last time with the Reichsführer of the SS Heinrich Himmler , although it remains open whether he wanted to sound out at this meeting to what extent he could use Himmler's contacts to middlemen in the West for himself. In any case, he stayed with Karl Dönitz in Schleswig-Holstein and after Hitler's suicide belonged to the Dönitz cabinet .

Nuremberg trials and prison time

Albert Speer was arrested by the British in Glücksburg Castle on May 23, 1945 . He was flown to Bad Mondorf with the other members of the government who were in the nearby special area Mürwik in Flensburg - Mürwik . Since it was not yet clear whether he should be brought to trial, he was initially given special privileged treatment. In June he was brought near Paris and then to Kransberg and questioned there. It was not until the end of September 1945 that he was taken to Nuremberg prison with the other major war criminals .

In the Nuremberg war crimes trial (1945-1946) Speer was sentenced to 20 years in prison on October 1, 1946 for war crimes and crimes against humanity , which he spent as inmate no. 5 in the allied war crimes prison Spandau . His long-time secretary Annemarie Kempf had tried as a witness through positive statements and collected exonerating material to soften the judgment. The death penalty escaped Speer very scarce. First, the Soviet and American judges voted for death by hanging , while the French and British judges wanted to impose prison sentences. Since a majority was necessary, the vote had to be repeated later, in which the American judge was finally able to change his mind.

In the course of the Nuremberg Trials , Speer had claimed that he wanted to kill Hitler in a gas attack in February 1945 . He later admitted that he never really could have made up his mind. The allegedly planned gas attack never came about. According to Speer's testimony at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, because Hitler suddenly ordered that the air shaft of the underground bunker be equipped with a four-meter-high concrete chimney. He also claimed to have commissioned an industrialist close to his ministry to procure the gas. He did not cite political reasons as the reason for dropping the plan, but the construction of this chimney. This justification was already questioned during the trial, but the alleged assassination plan itself was very likely fictitious. This is suggested by a rediscovered document from UK Foreign Office files. The US interrogator in charge at the seventh session of the interrogations with Speer was Oleg Hoeffding (1915–2002), who was born in Russia and grew up in Berlin, along with an employee of the British Foreign Office named Lawrence, about whom nothing is known. Hoeffding reported to his superior in a memo dated June 1, 1945 about his "seventh meeting with Speer". The paper later reached the British National Archives , presumably through Lawrence . Another version of Speer was recorded there, according to which he had hired someone by the name of Brandt to procure the poison gas. The interrogating Hoeffding added in brackets: "Hitler's doctor?", Because Karl Brandt was the only one with this name who had access to both the inner circle of Hitler and presumably poison gas, as he was jointly responsible for the euthanasia murders from 1939 to 1939 1941. Speer stated at the time that he had renounced the planned assassination attempt for political reasons in order not to promote a new stab in the back legend . Speer wanted to take care of the introduction of the poison gas into the conference room through an air shaft. Since he presented himself in 1946 as an apolitical technocrat who merely kept the German armaments going, the first version, that he had renounced his assassination out of political foresight, namely in order to avoid creating new legends, no longer fit into his new basic concept . These changes in the presentation of the alleged assassination plans were risky, but he got away with it.

What is particularly noticeable about the alleged assassination plan, however, is that it was supposed to take place in the same way as the Speer allegedly unknown mass murder of Jews and other groups of victims in Auschwitz and the other extermination camps. In the Moscow Declaration of October 30, 1943, the anti-Hitler coalition had already announced that it would bring the leadership of the Nazi state and war criminals to justice. Speer, who had already risen well in the Nazi state, could already be sure at the time that he would be charged and face the death penalty for his actions. At that time, the court was not yet aware of the document introduced in May 1948 in the trial against Oswald Pohl , the head of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office (WVHA), on the agreement between Speer and the SS entitled "Expansion of the Auschwitz Barracks Camp as a result of migration to the east" , which showed that Speer not only knew about Auschwitz directly , but also negotiated with Pohl and Himmler about the deportation and extermination process that was taking place.

Speer was the only one of the defendants to acknowledge a responsibility for the atrocities of the Nazi state, which he formulated in a very general way, but always denied any personal guilt. This is considered to be one of the main reasons Speer escaped sentencing to death. As the ex-boss and initiator of his forced labor program, he succeeded, for example, in blaming the victims on Fritz Sauckel. While Speer was the only one among the defendants who pretended to have recognized too late that Hitler and his regime - to which he himself belonged - was criminal and therefore supposedly had to be overcome, the other defendants disapproved of the entire process from the outset and completely refused. This benefited him, as a result he could - with a lot of skill - stage himself. Many other main defendants helped him with this without meaning to.

Goering in particular had him in his sights early on, because Speer was expressly repentant. When the defense attorney asked Speers at a testimony: "Mr. Ohlendorf, have you ever heard that Speer was planning an assassination attempt on Hitler?", He replied with "No". The main witness for the prosecution Otto Ohlendorf could not have known the very questionable assassination plan. Goering demonstratively jumped up, revolted and immediately took sides with Hitler, while Speer thereby moved into a light as a quasi courageous and determined opponent of Hitler. In the course of the proceedings, Speer triggered empathy for himself in a certain way and at the same time was able to distract from his victims. Speer's apparently critical account of National Socialism was not only well received by the judges. The Nuremberg Trial can be seen as the beginning of a lifelong successful defense and concealment strategy by Speer.

During his imprisonment, former employees and cooperation partners Speers supported his wife Margarete Speer financially on the initiative of Rudolf Wolters , after she complained to Wolters in 1948 that she needed 100 marks a month for the children's school fees alone. Successful entrepreneurs, such as Walter Rohland and Willy Schlieker , who was head of the official group in the Ministry of Armaments under Speer, and Speer's architects , among others, once again contributed to the fund set up by Wolters . By 1966 a total of around 150,000 DM was collected in this fund, known by Wolters as the “school money account”. Speer was released after serving his sentence on October 1, 1966, because the Soviet Union had refused a pardon. His secret records of the detention, the same daily routine and the conflicts among fellow prisoners as well as memories of Hitler, which were secretly created during this time, were smuggled out and later used in the two successful books Memories of 1969 and Spandauer Tagebücher of 1975.

After imprisonment

After his release from prison in Spandau in 1966, Speer lived mainly in the Heidelberg villa, Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg 50, which his father had built in 1905 and which is still owned by the family today. Financially, he was able to lead a carefree life. Sources of income were receipts from preprints, books and interviews. He also regularly and secretly sold works from a Nazi looted art collection (including six early romantics with Arnold Böcklin : Landscape from the Pontine Marshes and Italian Landscape by Jakob Philipp Hackert ), which he had bought from Karl Haberstock from 1938 . Business partner Robert Frank (1879–1961) had reported them stolen or missing, smuggled them to Mexico and hidden them there. Robert Frank, who later gave the Landesbergen power station its name , after a night-and-fog transport accompanied by Speer personally, which was only mentioned incidentally in his autobiography, had the paintings on April 23, 1945 in a Vorwerk of Schloss Grube (located in the today's Prignitz district ). While Speer was in Spandau prison, Frank wrote to a confidante of Speer that 2/3 of the paintings had been stolen on the way to Hamburg and that they had great difficulties with the pictures because some of them came from Jewish property. In reality, Frank got the pictures from Hamburg to Mexico. The managing director of the Kunsthaus Lempertz , Hendrik Hanstein , spoke of approx. DM one million proceeds from the paintings for Speer alone, which Speer had paid out in cash from Lempertz and which he had kept secret from his wife until his death. The other half went to the heirs of Robert Frank, with whom Speer, after a long dispute with Frank, had agreed on a discreet settlement and split in half, after the executor in Mexico came across the paintings in 1978. For the preprint of his memoirs Speer received 600,000 DM from the daily newspaper Die Welt .

Speer died in 1981 after an interview with the BBC in a hotel room in London in the presence of his German-English girlfriend as a result of a stroke . Albert Speer was buried in the Bergfriedhof in Heidelberg.

family

In the summer of 1922 Speer met Margarete Weber (1905–1987), who was the same age and came from a family of craftsmen in Heidelberg. Albert and Margarete married on August 28, 1928 in Berlin against the will of Speer's mother, who considered the daughter-in-law to be “not befitting”. Margarete Speer gave birth to six children (Albert, Hilde, Margret, Arnold, Fritz and Ernst) between 1934 and 1942. Some of Albert Speer's children are well-known personalities. His son Albert was also an architect and became an international city planner. His daughter Hilde Schramm is an educational scientist and a former member of the Alternative List in the Berlin House of Representatives , of which she was Vice President in 1989/1990. In 2004 she received the Moses Mendelssohn Prize for her commitment to the Foundation for giving back artistic and scientific work by as yet unknown Jewish women . His daughter Margret, b. June 19, 1938, studied archeology in Heidelberg. On April 14, 1962 she married the archaeologist Hans J. Nissen , with whom she lived for a while in Baghdad , and has been called Margret Nissen ever since. She became a photographer who devoted herself particularly to architecture, garden and plant photography. In 2004 she published a book about her father. His son Arnold (born 1940) was initially given the name "Adolf", which was later changed.

Speer's relationship with Hitler

Speer himself was impressed by him and his visions, ideals, his intuitive adaptability and his charm as early as 1930, when he first took part in a rally at which Hitler appeared as a speaker. Speer later said: "If Hitler had had friends, I would definitely have been one of his close friends."

Hitler, in turn, found the architect in Speer who, with organizational talent, could create large structures for him in the shortest possible time and with whom he could parley about art. Most of all, he valued Speer's loyalty. Hitler was interested in art in general, but above all in architecture, and granted Speer all possible means for his buildings. (Quote Speer: "Like Faust , I would have sold my soul for a large building . Now I had found my Mephisto .") Speer had his own interests and goals, which he was most likely to pursue as an architect of Hitler's building ideas, such as those Redesign of Berlin into the “ Imperial Capital Germania ”, a super-Rome and a super-Paris at the same time. Speer embodied in Hitler's eyes what he would have liked to be: an artist and visionary.

Self-stylization

Since his imprisonment in Nuremberg and Spandau, Speer worked on using extensive secret written records (which were smuggled outside to his friend Rudolf Wolters in Coesfeld with the help of a nurse ) to improve his somewhat positive image as an apolitical technocrat and misguided idealist through the Nuremberg trial to stabilize and conceal all negative points of his biography (promotion of the expansion of the concentration camp, expulsion of Jews from Berlin). Especially in his two very successful book publications, the Memoirs of 1969 and the Spandau Diaries of 1975, he partially reversed decisive phases of his work in the “Third Reich”. He presents himself as an expert who hardly knew about the crimes of the regime and “only did his duty”. Speer's memoirs focus on the years 1933 to 1945, where he describes in detail his relationship with Hitler. Speer takes a critical look at his role in the Nazi era and does not deny his basic responsibility, but, according to Heinrich Schwendemann, withholds essentials. Had to the published version of the text of the prepared in the Spandau years memoirs on behalf of Wolf Jobst Siedler , the then managing director of the Ullstein publishing house , Joachim C. Fest participated. For a long time this book promoted the “Speer legend” of the “Gentleman Nazi”. The Speer biography of the historian Magnus Brechtken , published in 2017, confirms Schwendemann's assessment by confronting Speer's stories with the sources. Speer's memoirs, with a worldwide circulation of almost three million copies, were apparently authentic eyewitness accounts that shaped the historical image of a small group of criminals around Hitler who were responsible for war, the Holocaust and slave labor , while Speer did not want to have known about it.

The Spandau Diaries , in which Speer describes the years of his imprisonment and at the same time remembers his time in the closest Nazi leadership circle, served the same purpose , taking into account the peculiarities of his fellow prisoners ( Baldur von Schirach , Rudolf Hess , Karl Dönitz , Erich Raeder , Konstantin von Neurath , Walther Funk ) describes and ridicules. The legend that he had the New Reich Chancellery built in less than twelve months is repeated in both books (and thus a legend conceived by Nazi propaganda to underpin the alleged efficiency of the Nazi system). The Speer biographer Magnus Brechtken describes the diaries, allegedly presented as authentic in Speer's foreword, as "literary invention" in the light of the sources. They presented a young, artistically talented architect wrestling with himself, seduced by Hitler, who actually never wanted to have anything to do with politics - and certainly with war and crime. Nevertheless, after having formally entered the inner circle of directors, he assumed abstract responsibility and was imprisoned without being guilty of any specific crimes committed by others.

Millions of copies of both books were sold worldwide; Speer had received an advance of DM 100,000 for the memories from Ullstein Verlag. In a television interview after his release in 1966, Speer claimed not to have known about the mass murder of Jews and other minorities during the German occupation. However, Speer was in Posen on October 6, 1943 with the Reich and Gauleiter and gave a speech there. Then, from 5:30 pm to 7:00 pm, Himmler spoke openly about the Holocaust in the second of his “ Posen Speeches ”. Speer's admission that he had previously left and that he had never heard of it from fellow participants, is described by Gitta Sereny as "simply impossible". In 2007, letters appeared from Speer about it, in which he admitted his presence at the speech. Historian Magnus Brechtken emphasized in his Speer biography in 2017 that the facts are clear: "All contemporary documents testify to Speer's stay in Posen, all claims to the contrary are post-war formulations ".

New documents found in 2005 suggest that Speer not only knew about the expansion of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp , but also actively promoted it. The selection of prisoners into those who were fit for work for the armaments industry and the old, sick and children destined for extermination corresponded to his interests. As an armaments minister he needed forced labor and as general building inspector for the Reich capital he had carried out the mass deportation of Berlin's Jews for the redesign of Berlin.

Speer's publications also caused a falling out with many former employees and companions who accused him - like circles of the intellectual left - of completely submitting to the zeitgeist again as in the 1930s . According to this, Speer is an uncertain opportunist who tried to gain a foothold in the public eye of the Federal Republic. His relationship with his close student friend, Rudolf Wolters, finally collapsed. This came up against the discrepancy between Speer's public confession of penance and his lifestyle as well as Speer's alleged break with Hitler, which was only made public by Speer after 1945. Albert Speer, according to Wolters, was "a man for whom money and reputation were decisive". As a result, Wolters made his files available to the historian Matthias Schmidt , who published his first critical biography of Speer in 1982.

According to the historian Magnus Brechtken, Speer acted anti-Semitically as soon as the practical possibility and personal advantage arose, even if he did not correspond to the cliché of a typical anti-Semite who made anti-Semitic speeches. He was seen as a staunch National Socialist who acted accordingly. As an example, he cites the fact that in 1938 he needed living space in Berlin for his renovation plans and then started the “registration of Jewish apartments” on his own initiative.

Speer's self-staging in his book Memories does not apply to other points either. For example, out of idealism, he had waived fees and could only afford his house in Berlin- Schlachtensee with financial support from his father. Because of his proximity to Hitler, however, he was able to access unlimited resources, as there was no state control over his orders. Speer took advantage of this. In 1942, for example, he presented the models for the future Berlin, the later so-called Germania plans , for which he received 60,000 Reichsmarks per month, although he did not have to do anything more for the project. Just a few days before the end of the war, he flew to Berlin for the “ Führer Birthday ” and had a 30,000 Reichsmark advance payment for travel expenses, although he did not incur any costs. That would be the equivalent of around 123,000 euros today. This was typical of the top Nazi officials, and Göring, for example, made no great secret of it.

Brechtken considers the widespread legend that Speer ignored Hitler's final phase orders to destroy infrastructures in Germany, and thus made the subsequent economic miracle possible, particularly spectacular . Particularly noticeable is the episode in Speer's "Memories", that allegedly shortly before the end of the war in the Führerbunker he confessed this refusal to command Hitler and left him with tears in his eyes, because this scene was invented in 1952 by a French journalist. Speer found it useful and therefore made it his own in the book.

The historian Wolfgang Schroeter sums up Speer's overall myth of his alleged "personal integrity including all sub-myths about his achievements" as formulated in his memoirs :

- "the myth of the apolitical artist and technocrat (1)

- the myth of the armaments miracle created by Speer (2)

- the myth of its importance for the modernization of Germany (3)

- the myth of his position as "second man in the state" (4)

Speer's apologetic and highly selective treatment of his perpetrators and the crimes of National Socialism ... includes [the following] sub-myths:

- the myth of his personal integrity and ignorance of the Holocaust (5)

- the myth of his alleged opposition to Himmler and the SS (6)

- the myth of his resistance to Hitler (7) "

reception

The Observer wrote about Speer and his colleagues in April 1944 that they are exemplary of a new type of “successful” average person with conventional political views, “who knows no other goal than to make his way in the world, only by means of his technical ones and organizational skills. [...] We may get rid of the Hitlers and Himmlers, but the Speers will be with us for a long time. ”Former concentration camp intern Jean Améry wrote of Speer that he regrets“ most lucratively ”. Joachim Fest (1926–2006), who as editorial advisor to Speer's publications and thus played a key role in his self-styling, later stated that Speer had "turned our noses with the most honest expression in the world."

“Speer is a prototype for the social group of functional elites who consciously decided in favor of Hitler and who gave National Socialism its real dynamism through their specialist knowledge. Without all the doctors, lawyers and administrators, the rule could not have worked so well. Speer was basically just one of the most dedicated, ambitious and hardworking. That's why after 1945 he was the ideal figure for anyone who wanted to say: “I took part, but I didn't notice anything about the crimes.” Even people who marched at the very front were supposedly not involved afterwards. Speer, like everyone else, knew exactly what he had done. He later very successfully denied this and suppressed it. "

The view of Albert Speer has changed over three post-war generations. While the war generation identified with Speer's innocence legend as unsuspecting, the " 68 generation " was only able to establish itself late with a culture of remembrance , before Magnus Brechtken's bestseller and the Nuremberg special exhibition he helped to create succeeded in refuting Speer's legend with new scientific findings. But the family memories of the third and fourth generation are also influenced by films like “Schindler's List”. There is still the "good Nazi", as Speer played him in the 2004 film " Der Untergang ". In fact, the fourth generation is already showing a trend towards its fictionalization, medialization and virtualization, as in the novel Die Wohlgesinnten by Jonathan Littell, where Speer appears on over a hundred pages, and in Timur Vermes' Er, due to the time lag behind the “Third Reich” is back and in the movie Inglourious Basterds , where reality is turned upside down and Speer no longer plays a role.

Fonts

- Memories . Ullstein, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-549-07184-1 . ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list in 1969 and 1970 )

- Spandau diaries. Propylaea, Berlin a. a. 1975, ISBN 978-3-549-17316-9 . ( Number 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from September 15, 1975 to February 15, 1976 ) Many other issues.

- The slave state. My argument with the SS . Ullstein, Berlin 1981, ISBN 978-3-421-06059-4 . (Many more issues)

- The Kransberg Protocols 1945. His first statements and notes, June - September. Ed. Ulrich Schlie. FA Herbig, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7766-2288-1 .

literature

Biographies

- Adelbert Reif : Albert Speer. Controversies about a German phenomenon. Bernard and Graefe, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-7637-5096-7 .

- Matthias Schmidt : Albert Speer. The End of a Myth - Speer's Real Role in the Third Reich. Scherz, Munich a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-502-16668-4 . (Also dissertation, FU Berlin). (Several new editions as paperback, most recently Netzeitung Berlin 2005)

- Gitta Sereny : Wrestling with the truth. Albert Speer and the German trauma. Translated from the English by Helmut Dierlamm. Kindler, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-463-40258-0 (new edition 2005 by Goldmann, Munich, ISBN 3-442-15328-X ).

- Dan van der Vat: The good Nazi. The Life and Lies of Albert Speer. 1997 (German: The Good Nazi. Life and Lies of Albert Speer .) Translated from English by Kurt Baudisch and Frank Jankowski . Henschel Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89487-275-6 .

- Joachim Fest : Speer. A biography. Alexander Fest Verlag, Berlin 1999, ISBN 978-3-8286-0063-8 . (Other editions, especially as a paperback) Review by Volker Ullrich in der Zeit . No. 39/1999. Volker Ullrich, The Speer Legend

- Heinrich Schwendemann : architect of death . In: Die Zeit No. 45/2004: “In autumn 1944, NS armaments chief Albert Speer was at the height of his power. Still fondly lied to the "seduced citizen" today, Speer was actually one of the regime's most brutal leaders. "

- Heinrich Breloer : On the way to the Speer family. Encounters, conversations, interviews. Propylaea, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-549-07249-X .

- Joachim Fest: The unanswerable questions. Notes on conversations with Albert Speer between the end of 1966 and 1981. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-498-02114-1 .

- Margret Nissen with the assistance of Margit Knapp and Sabine Seifert: Are you Speer's daughter? DVA, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-421-05844-X .

- Jonas Scherner, Jochen Streb: The end of a myth? Albert Speer and the so-called armaments miracle. In: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 93 (2006), pp. 172–196.

- Adam Tooze , Yvonne Badal (translator): Economy of Destruction. The history of the economy in NS. Siedler, Munich 2007 (first English 2006) ISBN 978-3-88680-857-1 , passim, esp. P. 634 ff. bpb (series of publications by the Federal Agency for Civic Education; Volume 663), ISBN 978-3-89331-822-3 . New edition: Pantheon, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-570-55056-4 . (For a review or a summary interview, see Netzeitung and Die Zeit )

- Adam Tooze: The Blitzkrieg That Wasn't . In: Die Zeit No. 27/2007.

- Alexander Kropp: Tracking down forgeries: Hitler's "favorite architect" Albert Speer and his official diary - an edition project. Announcement in Uni.vers: the magazine of the Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg / UNIBA. - 7 (2007), p. 33ff. PDF document

- Ludolf Herbst : Speer, Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , pp. 644-646 ( digitized version ).

- Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-76909-1 .

- Martin Kitchen: Spear. Hitler's Architect. Yale University Press, New Haven 2015, ISBN 978-0-300-19044-1 .

- Isabell Trommer: Justification and discharge. Albert Speer in the Federal Republic. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 2016, ISBN 978-3-593-50529-9 .

- Magnus Brechtken : Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-8275-0040-3 .

- Roman B. Kremer: Autobiography as an apology. Rhetoric of justification in Baldur von Schirach, Albert Speer, Karl Dönitz and Erich Raeder. (= Forms of memory 65). V&R unipress, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8471-0759-0 ; Review hsozkult

- Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2018, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 .

Architecture and urban planning

- Joachim Petsch: Architecture and town planning in the Third Reich. Munich, Hanser 1976, ISBN 3-446-12279-6 .

- Lars Olof Larsson : The redesign of the imperial capital. Albert Speer's general development plan for Berlin. Hatje, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-7757-0127-3 .

- Léon Krier : Albert Speer: Architecture 1932–1942. Les Archives d'Architecture Moderne, Brussels 1985, with an introduction by Lars Olof Larsson, ISBN 978-2-87143-006-3 (English, French).

- Susanne Willems : The evacuated Jew. Albert Speer's housing market policy for the Berlin capital construction. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89468-259-0 .

- Heinrich Schwendemann : "Drastic Measures to Defend the Reich at the Oder and the Rhine ..." A forgotten Memorandum of Albert Speer of March 18, 1945. In: Journal of Contemporary History. 38th year 2003, pp. 597-614.

- Dietmar Arnold : New Reich Chancellery and “Führerbunker”. Legends and Reality. Links, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86153-353-7 .

- Lars Olof Larsson, Ingolf Lamprecht: “Happy New Design” or: The Gigantoplanie of Berlin 1937–1943. Albert Speer's general development plan in the mirror of satirical drawings by Hans Stephan. Ludwig, Kiel 2009, ISBN 978-3-937719-69-6 .

- Sebastian Tesch: Albert Speer (1905-1981) (= Hitler's architects . Volume 2 ). Böhlau, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-79595-7 .

exhibition

From April 28, 2017 to January 6, 2018, the exhibition Albert Speer in the Federal Republic was in the Nuremberg Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds . To see from dealing with the German past . The volume of the exhibition by Martina Christmeier and Alexander Schmidt (eds.): Albert Speer in the Federal Republic was published . The exhibition also included video interviews with historians who have presented studies on Albert Speer's role in National Socialism over the past few years and decades. They answer the questions Speer refused to answer. These videos are also available on the website of the Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds.

Film and funk

- Heinrich Breloer (script and direction): Speer and Er . Docudrama . Germany, 2004.

- Artem Demenok (script and direction): World capital Germania . Documentation. Germany, 2005.

- Reinhard Knodt: Speer and We. Radio documentary, Bayerischer Rundfunk . Germany, 2005.

- Marcel Ophüls - The Memory of Justice (German: not guilty?) , Documentary from 1976 in which Speer speaks over long periods.

- Nigel Paterson (Director): Nuremberg - The Trials - Albert Speer - Career Without Conscience. Great Britain, 2006, 59 min. German version BR. (Docu-drama that combines eyewitness accounts and archive material with re-enacted scenes.)

- Secrets of the "Third Reich". 6th, Speer's Deception. ZDF, documentation. Germany, 2011.

- 2015: Speer, Architektur und / ist Macht, theater monologue by “Gli Eredi”, with Ettore Nicoletti, text by Kristian Fabbri. The text received the “Autori Italiani - 2015” award in the monologues section of the Carlo Terron Theater Foundation.

- Stephan Krass: The spearman. Radio play with Matthias Brandt and Caroline Junghanns. Südwestdeutscher Rundfunk (SWR). Germany, 2015.

- Vanessa Lapa : Speer Goes to Hollywood . Documentary. Israel, 2020. (Documentation based on sound recordings of Speer's collaboration with screenwriter Andrew Birkin on a biography film that was ultimately never made.)

Web links

- Literature by and about Albert Speer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Albert Speer in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- “Speer und Er” ( Memento from April 5, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), WDR website for Heinrich Breloer's four-part docu-drama from 2004.

- Website of the Nuremberg Trials Memorium

Biographies

- Gabriel Eikenberg: Albert Speer. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Albert Speer (1905-1981). (Not available online.) In: shoa.de . Archived from the original on February 22, 2009 ; accessed on August 14, 2018 .

- Albert Speer Sr. In: arch INFORM .

- A pride that destroyed worlds . faz.net, 2004

Individual evidence

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 57–61.

- ↑ Winfried Nerdinger : www.bauwelt.de/themen/buecher/Albert-Speer-Eine-deutsche-Karriere-2865936.html

- ↑ Ulrich Herbert : www.taz.de/!612524/

- ^ Joachim Lilla : extras in uniform. The members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 627.

- ^ State Archives Administration Baden-Württemberg (ed.): The city and districts of Heidelberg and Mannheim. Official district description. Vol. 3: The city of Mannheim and the municipalities of the Mannheim district. Braun, Karlsruhe 1970, p. 77.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 28–37.

- ^ Albert Speer, the architect in Guido Knopp: Hitler's Helpers . Bertelsmann, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-570-12303-0 .

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 9–15, especially p. 11.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 35ff.

- ↑ Albert Speer: Memories . Ullstein, 2005.

- ↑ May 1, 1933 - First major order for Albert Speer

- ^ A b Dietmar Arnold: New Reich Chancellery and "Führerbunker" - Legends and Reality. 1st edition. Berlin 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Rüdiger Hachtmann, Winfried Süß: Hitler's commissioners: special powers in the National Socialist dictatorship. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-8353-0086-5 . Comparable were, for example, Fritz Todt as "General Inspector for German Roads" or Hermann Göring as "Commissioner for the four-year plan".

- ↑ Rainer Eisfeld : Moonstruck, Wernher von Braun and the birth of space travel from the spirit of barbarism . 2012, ISBN 978-3-86674-167-6 , p. 103.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 102.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, p. 265.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 141.

- ^ Heinrich Schwendemann: Speer. Architect of death . In: Die Zeit , No. 45/2004.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 147.

- ^ Hitler's architects: Troost, Speer, Fick and Giesler

- ^ Albert Speer: New German Architecture . Book ring People and Empire Prague, 1941.

- ↑ Albert Speer: Memories. Propylaea, Berlin 1969, p. 88.

- ↑ a b c d Werner Durth, Niels Gutschow: Dreams in ruins . Vieweg Friedr. + Sohn, 1988, ISBN 3-528-08706-4 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 , pp. 51 .

- ^ Gregor Janssen: The Speer Ministry: Germany's armament in war. 2nd Edition. Ullstein, Berlin 1969, p. 34.

- ^ Gregor Janssen: The Speer Ministry: Germany's armament in war. 2nd Edition. Ullstein, Berlin 1969, pp. 43-44, p. 47.

- ↑ Adam Tooze: Economy of Destruction. The history of the economy under National Socialism . Siedler, Munich 2007, p. 642.

- ↑ a b Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 166.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 201.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 279–282, p. 285.

- ↑ Jonas Scherner, Jochen Streb: The end of a myth? Albert Speer and the so-called armaments miracle. In: Quarterly for social and economic history. 93 (2006), pp. 172-196.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 205f. u. P. 653, note 5; on p. 208–213 there are further comparisons of Speer's claims about the “armament miracle”, which are checked or refuted with a fact check based on the sources.

- ^ Gregor Janssen: The Speer Ministry. Germany's armaments at war. 2nd Edition. Ullstein, Berlin 1969, p. 111, p. 135, p. 188-189.

- ^ Bernhard R. Kroener : "Menschenbewirtschaftung", population distribution and personal armament in the second half of the war (1942–1944). In: Military History Research Office (Hrsg.): The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 5.2, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt , Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-421-06499-7 , pp. 854-855.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 302-303; Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. Foreign civilian workers, prisoners of war and prisoners in the German Reich and in occupied Europe 1939–1945 . Stuttgart, DVA 2001, ISBN 3-421-05464-9 , pp. 229-231.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 303-307.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 172f.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 275f. and p. 679f., note 9.

- ^ Ian Kershaw , Höllensturz , Europa 1914 to 1949, pp. 484 f., Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich, 4th edition 2016, ISBN 978-3-421-04722-9

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: History of the West. The time of the world wars 1914–1945 . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-59236-2 , p. 984.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 294-297.

- ↑ a b c d Historians on Albert Speer: "He did everything for the final victory" . taz.de

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 300-301, pp. 307-310.

- ↑ Speer: Memories. Propylaen, 1969. / Ullstein, Berlin 2003, pp. 406-407; Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 307–328.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 , pp. 51 .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : History of the West. The time of the world wars 1914–1945 . CH Beck, Munich 2011, p. 1107f.

- ^ Schmidt, Mathias: Albert Speer. The end of a myth ... ; Bern-Munich 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 331–333.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 339–342.

- ^ Heinrich Schwendemann : Speer: Architect of death. In: Die Zeit , October 28, 2004.

- ^ Karl-Günter cell: Hitler's doubting elite. Goebbels - Goering - Himmler - Speer. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, pp. 333-335, p. 345.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 282–292.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 311.

- ^ Telford Taylor: The Nuremberg Trials. ISBN 3-453-09130-2 , p. 650.

- ^ The trial of the main war criminals before the International Military Tribunal: Nuremberg, November 14, 1945 to October 1, 1946. Nuremberg. Volume 16. 1949, p. 543. Gitta Sereny: The struggle with the truth: Albert Speer and the German trauma. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15141-4 , pp. 573-574.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 , pp. 105 .

- ↑ Quarterly Journal of Contemporary History , Issue 2/2019 (de Gruyter Oldenbourg Verlag, Berlin), pp 289-306.

- ^ This is how Albert Speer invented his "assassination attempt" on Hitler

- ↑ The beginnings of Albert Speer's survival strategy

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 310; It is the Nuremberg document NIK 15392, Pohl to Himmler, September 16, 1942.

- ↑ "Albert Speer as a National Socialist and commemorative constructor"

- ↑ a b Conversation with historians: Speer did not want to go to the gallows

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 313f.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 365.

- ↑ Sensing chest . In: Der Spiegel . No. 40 , 1966 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Hansjürgen Melzer: Hank stored Speer's pictures in the garage. In: General-Anzeiger (Bonn) . December 17, 2011, accessed April 26, 2019 .

- ↑ "Provenance Speer" Van Ham is auctioning a picture that once belonged to Albert Speer . FAZ , April 8, 2006; Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e Guido Knopp , Mario Sporn (editor) u. a .: Secrets of the "Third Reich" . Bertelsmann eBooks, 2011, ISBN 978-3-641-06512-6 , 416 pages.

- ↑ a b Uli Weidenbach: Speer's deception . ZDF documentation 2011.

- ↑ Phoenix , Uli Weidenbach: Secrets of the Third Reich. Speer's deception

- ^ ZDF: Speer's deception. The "good Nazi" and his entanglements .

- ↑ See Arnold / Reich Chancellery 2005, p. 151.

- ↑ Speer: Memories. Propylaea, 1969. / Ullstein, Berlin 2003, p. 517.

- ↑ Speer: Memories. Propylaeen, 1969. / Ullstein, Berlin 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ Gitta Sereny: Albert Speer. His struggle with the truth. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15141-4 , p. 733 f.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich : Speer's invention. How the legend about Hitler's darling came about and what role Wolf Jobst Siedler and Joachim Fest played in it. In: The time . No. 19/2005.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 385–419; There numerous other examples of the creation of legends by Speer, which contradict the sources on his actions before 1945.

- ↑ Joachim Fest reports this legend one more time without critical comment in his Speer book from 1999, although the real history of the building of the Reich Chancellery (started in 1934, provisionally completed only in 1943) had been known and published since 1982.

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 476–491, in particular pp. 478–482 (quotation, p. 478).

- ↑ Gitta Sereny: Albert Speer. His struggle with the truth. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15141-4 , p. 484; summarizing the controversy: Stefan Krebs, Werner Tschacher: Speer und Er. And we? German history in broken memory. In: History in Science and Education. Volume 58, 2007, Issue 3, p. 163 ff.

- ↑ Gina Thomas: Albert Speer - There is no doubt, I was there . In faz.net March 10, 2007 (Was Albert Speer present when Himmler announced the murder of all Jews? Unknown letters from the Hitler architect have now surfaced in London. The correspondence deepens and complements the conflicting picture of Hitler's architect.) Again in: Cape. 2 Mr Speer's business , by Stefan Koldehoff : The pictures are among us: The business of Nazi-looted art and the Gurlitt case , 2014

- ↑ Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, p. 463.

- ↑ Susanne Willems: The “Special Program Prof. Speer” in Auschwitz-Birkenau ( Memento from May 11, 2005 in the Internet Archive ). WDR , May 2005.

- ↑ Fest (1999), p. 443 f.

- ↑ van der Vat (1997), p. 552.

- ↑ Purchasing power comparisons of historical amounts of money. Deutsche Bundesbank, accessed on January 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Historians on Albert Speer: "He did everything for the final victory" . taz.de - on Hitler's final phase orders and Speer's attitude to this in detail Magnus Brechtken: Albert Speer. A German career . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2017, pp. 277–282.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 , pp. 62-63 .

- ↑ after Werner Durth , Deutsche Architekten. Biographical entanglements 1900–1970. Braunschweig 1988, p. 202.

- ↑ Jean Améry: Essays on Politics and Contemporary History , Klett-Cotta, 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Joachim Fest: The unanswerable questions. Notes on conversations with Albert Speer between the end of 1966 and 1981. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-62159-2 , p. 257.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schroeter: Albert Speer. The rise and fall of a myth . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78913-6 , pp. 352-357 .

- ↑ Schwendemann: Review. In: Die Zeit , No. 7/2005.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe : "Ignorant" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 22 , 2017, p. 48-50 ( online ).

- ↑ See Rolf-Dieter Müller : Later execution not excluded… . In: FAZ , June 6, 2017; Political Books , p. 7.

- ↑ Albert Speer in the Federal Republic. On dealing with the German past

- ↑ In the series of publications of the museums of the city of Nuremberg, Volume 13. Verlag Imhof, Petersberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-7319-0561-5 .

- ↑ Patrick Bahner: Free ride for the Reichsminister a. D. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung No. 121 of May 26, 2017, page 11 (report on this exhibition).

- ↑ Expert interviews on questions Speer did not want to answer

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Speer, Albert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Speer, Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German architect, politician (NSDAP), MdR and high functionary during the Nazi era |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 19, 1905 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mannheim |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 1, 1981 |

| Place of death | London |