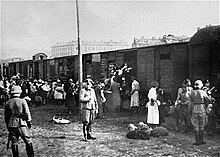

Deportation of Jews from Germany

The systematic deportation of Jews from Germany to the East began in mid-October 1941, i.e. before January 20, 1942, the day of the Wannsee Conference . Sources point out that Adolf Hitler made this decision around September 17, 1941. Most of the Jews deported from the German Reich were not murdered directly at their destination. Individual transports ended up in the Sobibor or Maly Trostinez extermination camps in 1942 , but most of the deportees were initially held in ghettos or labor camps under adverse living conditions . Many died there, others were later transported to the extermination camps and murdered there. From the end of 1942, the trains went straight to Auschwitz-Birkenau .

In the case of the deportations to the ghettos, concentration and extermination camps in the east and the so-called “ Final Solution ”, two state authorities (and their subordinate agencies) were of central importance: Department IV B 4 of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) and that since 1937 in the Deutsche Reichsbahn incorporated into the Reich Ministry of Transport , which was responsible for passenger and freight traffic throughout Europe, which was ruled by the National Socialists. The deportations and mass murder were only possible at all if these two state authorities worked closely together. Without the rail network, the availability of railway trains and the countless smoothly functioning employees of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, the transports to the extermination camps and the murder of millions of European Jews, Sinti and Roma etc. a. not been feasible. In addition to Gestapo officials, customs officers, bailiffs, administrative officials, timetable designers, police officers as security guards and many others were involved in the deportation of Jews from Germany , whose 'contribution' was indispensable for a smooth process.

In official German correspondence and in guidelines, the term deportation was mostly trivialized and apparently technically circumscribed; the Jews were "evacuated", "evacuated", "resettled", "evacuated" or "emigrated", a "residence transfer to Theresienstadt" carried out and the empire "emptied of Jews and liberated."

Early deportations

The earliest deportations from the “ Greater German Reich ” concerned Jews of Polish nationality. On October 28 and 29, 1938, up to 17,000 Jews were brought to the Polish border in up to 30 special trains in the so-called Poland Action and deported there across the border. This first National Socialist mass deportation, which took place in the interaction of the police, Reichsbahn, tax authorities and diplomacy, can be seen as a prime example of the later deportations of Jews. The security service (SD) resorted to logistical cooperation with the Reichsbahn when it had more than 26,000 Jews transported to concentration camps a little later after the November pogroms in 1938 .

Under the leadership of Adolf Eichmann's " Central Office for Jewish Emigration ", around 4,000 Jews from Vienna, Mährisch-Ostrau and Kattowitz were deported to Nisko in October 1939 . The plan to deport around 65,000 Jews was stopped at the end of October and in December 1939 Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler prohibited it “until further notice”. In his function as " Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Volkstum ", Himmler gave priority to the settlement of ethnic Germans in the annexed Polish areas .

In order to create living space for Baltic Germans "returnees", around 1,000 Jews from Gau Pomerania - mainly from Stettin - were deported to Lublin in February 1940 . On the evening of February 12, two SA men went to each Jewish apartment, monitored the packing, put out the stove and sealed the doors. The exact procedure was explained in a detailed leaflet. It is controversial whether this was just a single action by the President of Pomerania, which was supported by the local Stapo control center, or whether the Reich Security Main Office, contrary to its assertion to the Reich Association , was informed of it beforehand.

When Jews were deported from southwest Germany in 1940 - also named Wagner-Bürckel-Aktion after the responsible Nazi Gauleiter - since October 21 and 22, 1940, more than 6,000 Jews from Baden and the Saar-Palatinate were deported to the Camp de Gurs in France . The occupied country was obliged to “take over” Jewish people from occupied departments into the interior of the country. By mid-September 1940, over 23,000 French Jews and other unpopular French were deported from the occupied territories. The Jews from Baden and Saarpfalz were "sent along" by the Gauleiters. Adolf Eichmann was personally present to guide the trains over the inner-French demarcation line. According to the historian Peter Steinbach , the deportation of Jews from southwest Germany was paradigmatic for the later deportations from all over Germany; the "Jews' campaign in Baden and in the Palatinate" had been prepared for a long time and had delivered a kind of "master plan".

In February and March 1941, around 5,000 Jews from Vienna were transported to the Generalgouvernement in five transports "in view of the particularly camped conditions", namely the complained lack of living space in Vienna . Only 70 of them survived the end of the war .

In these cases the Gauleiter usually seized a favorable opportunity to remove Jews from their area; the systematic deportation of German Jews did not begin until later. Heinrich Müller and Adolf Eichmann had already gained significant experience in the organization and technical implementation of the subsequent mass deportation . Organizational processes were refined and recorded in leaflets; Ministries drafted ordinances on the Reich Citizenship Law so that deportees lost their German citizenship and their assets could be confiscated easily.

Mass deportation from the German Reich

By the decree of October 18, 1941, by which Heinrich Himmler prohibited all Jews from being allowed to emigrate with effect from October 23, more than 265,000 Jews - the Reichsvereinigung named the number of 352,686 people - had left the "Old Reich". At the end of October 1941, 150,925 people defined as Jews were still living in the “Altreich”, including a disproportionately large number of women and old people. There is evidence that 131,154 of these German Jews were deported. In addition, almost 22,000 who had previously fled to neighboring countries were later imprisoned and abducted.

The systematic mass deportations of German Jews to the East began on October 15, 1941. In September 1942 there were only 75,816 Jews in the "Altreich". With the “ factory action ” in March 1943, the mass deportation was completed. Around 15,000 Jews were initially spared deportation because they were mixed marriages or had been in hiding.

Responsibilities

With the law on the reorganization of relations between the Reichsbank and the Deutsche Reichsbahn of February 10, 1937, the name changed from Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft (DRG) to "Deutsche Reichsbahn" (DR), which was organizationally affiliated to the Reich Ministry of Transport. This placed rail transport directly under the sovereignty of the empire.

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, the annexed parts of Poland were added to the Reich Railway Directorate Districts Opole and Breslau and the newly established Reich Railway Directorate Danzig and Posen ; the " General Directorate of the Eastern Railway - Gedob" was responsible for the German-occupied part of Poland . From January 1942, the Reich Ministry of Transport took over the organization of rail traffic in the occupied part of the Soviet Union (General Directorate East, based in Warsaw). In the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Adolf Eichmann's Section IV B 4 was involved in ordering trains; Division 21 "Mass Transportation" with Division 211 "Special Travel Trains" was responsible for the Reichsbahn.

Eichmann's department often requested the special trains six weeks in advance and the Reichsbahn generally provided them as requested. In December 1941 and 1942 the deportation transports were reduced because the Wehrmacht used all capacities for Christmas holiday trains . A general transport ban imposed by the Wehrmacht in preparation for the 1942 summer offensive slowed the speed of the deportations, but did not prevent them.

On July 26, 1941, the responsible department EI in the Reich Ministry of Transport under the ministerial director Paul Treibe issued a special tariff for mass transports of "Jews and foreign people for resettlement from the German Reich". Thereafter, "half the 3rd class fare" should be charged with 2 Reichspfennig per kilometer. This price should also apply to traffic outside the Reich borders and was later calculated equally for passenger transport with freight wagons. These transports were at best cost-covering and the Deutsche Reichsbahn did not make any significant profit.

The Reichsbahn and its means of transport

For the first deportations of German, Austrian and Czech Jews in 1941/1942 to Litzmannstadt , Minsk , Kowno , Riga and the Lublin district , the Reichsbahn regularly used passenger cars . For the mass transports to the “ old people's ghetto” Theresienstadt , which began in June 1942, around 20 older third- class passenger cars , a few covered freight cars for luggage and a second-class passenger car for the escort unit were provided for around one thousand people . Several hundred smaller but more frequent transports to the Theresienstadt concentration camp followed, for which the Reichsbahn coupled one or two passenger cars to scheduled trains to Dresden and Prague.

While freight trains with an average of 3,750 Jewish victims rolled as passengers in the east , covered freight wagons were initially only used in a few exceptional cases within the German Reich in order to be able to deport a large number of sick people who were unable to walk and who had to be transported lying down. According to Alfred Gottwaldt , the use of passenger cars was due to the lack of freight cars; however, he also suspects intent to deceive.

The need for supplies and the priority given to military transports led to transport bans, which, however, only caused slight delays in the deportation. In April 1942, "empty Russian trains / workers' transports" made up of 20 converted freight cars with 35 seats each were used, which were to be used for the deportation on the way back. Although actually only intended for 700 people, 1,000 deportees were to be transported and additional freight wagons provided; even the escort command should be satisfied with these cars .

From the summer of 1942 onwards, freight trains were used several times for deportations in Germany. exact figures are not available. There was a special type of "boxcar" intended for military transport; these “ cattle cars ” had devices for the transport of six horses and could be equipped with mobile benches for 48 soldiers. When survivors use the term “cattle wagon” in connection with deportations, it does not have to be exactly that type of wagon. In fact, the deportees were crammed together like cattle for days, so that the image of the “cattle wagon” comes to mind.

The travel speed for long-distance passenger express trains was 50 kilometers per hour in 1944. Deportation trains barely reached half of this average speed, as regular and Wehrmacht trains were given priority by evading and parking the transport of Jews on sidings .

Deportation notice

With its “Guidelines for the Evacuation of Jews”, the Gestapo specified the place and day on which the Jews who were forced to leave the country mostly had to go to a collection camp “to be smuggled through”. In June 1942, for example, people over a certain age limit (this was sometimes given as 60, 65 or even 68), workers from armaments factories, Jews from “ mixed marriages ”, “ valid Jews ”, holders of high awards for bravery and Jews of certain types were excluded from deportation Nationality. In addition, the amount of cash carried was limited and the maximum weight of luggage was set at 50 kg. Baggage should be searched and valuables should be confiscated. Bring a blanket and food for eight days. The Jews destined for deportation had to submit a declaration of assets; their homes were sealed.

The Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich Association of Jews in Germany) had a card index which the Gestapo accessed in addition to their own " Jewish card index ". Regional branches of the Reichsvereinigung also had to set up files according to the criteria of the Nuremberg Race Laws. The Jewish “Mittelstelle” in Württemberg, for example, even had to draw up deportation lists for the Stuttgart Stapo control center on this basis . The local employees of the "Reichsvereinigung" had to help deliver the deportation orders; they put together leaflets for luggage, helped with luggage transport and provided food at the collection points.

Reception camp

Jewish community halls, rented halls or halls, in which sometimes double bunk beds, sometimes only deckchairs or straw beds were available for the overnight stay, served as “reception camps”, in which the Jews destined for “evacuation” had to appear on the day before their departure. Tax officials collected and reviewed the eight-page property statement. According to the specially created 11th ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act of November 25, 1941, every Jew lost his German citizenship "with the transfer of his habitual residence abroad" ; at the same time the property fell to the German state when the border was crossed. A little later, Auschwitz in occupied Upper Silesia was also classified as “foreign within the meaning of the Eleventh Ordinance”. In the case of deportations to Theresienstadt , which was incorporated into the German Reich as a protectorate , - as was the case with deportations before this date - this provision could not be used. In order to maintain the appearance of legality , bailiffs were called in for deportations to Theresienstadt, who delivered a formal order to those waiting in the assembly camp, which referred to the statutory provisions of 1933 on “ confiscation of property that is hostile to the people and the state ”. In a decree dated June 30, 1942, the Reich Minister of the Interior stated that the Jews to be deported were all attached to "anti-people and anti-state efforts".

In addition to tax officials, to whom the Reich Ministry of Finance issued instructions under the code name “ Aktion 3 ” in November 1941 , numerous other people were involved in asset management: banks received copies of the transport lists in order to be able to record all savings. Appraisers, auctioneers and freight forwarders were involved in the dissolution of the households. Coal dealers received news about the stored fuel supply. Landlords who later asserted loss of rent for the sealed apartments submitted their claims to the tax authorities. In a regional study, 39 offices, institutions and people are listed who were directly or indirectly involved in the deportation and - just like with formal administrative acts - ensured planning and compliance with the requirements, precise cost accounting and smooth processes.

Before leaving, there were body searches and thorough baggage checks, during which even pennies and stamps were withheld. Initially, you were allowed to take 100 Reichsmarks with you; this sum was soon reduced to 50 Reichsmarks and had to be carried or exchanged as a "Reichskreditkassenschein" . The fare had to be paid in advance or paid by the "Reichsvereinigung".

journey

In accordance with an agreement with the security police , the order police guarded and escorted the transport trains to their destination; Any costs incurred were reimbursed to the Reichsbahn by the security police.

The confidential report by the transport manager Paul Salitter , who in December 1941 led a deportation train from Düsseldorf to Riga with 15 police officers, can serve as an example . This special train with passenger cars was supposed to leave Düsseldorf on December 11, 1941 at 9:30 a.m. with 1,007 Jewish people. That is why they were "made available" at the loading ramp from 4:00 am. On the way from the transit camp to the ramp, a man accused the tram to suicide to commit. A woman who was able to isolate herself in the dark was discovered and denounced by a railway employee .

The train arrived late. The time pressure meant that some cars were only occupied by 35 people, others were overloaded with 60 to 65 people and children were separated from their parents. Insufficient drinking water was given out. The heating failed in some cars. After a 61-hour journey, the train arrived at Skirotava near Riga at midnight and remained there for one night, unheated and with a frost of 12 degrees. The next morning the transport manager handed over “the RM 50,000 Jewish money he had carried with him” in the form of Reichskreditkassscheine to the Gestapo official there .

Destinations and dates

The destinations, dates and number of people on the deportation trains that transported German Jews from the Reich to the East have largely been reconstructed and published. Usually the further fate of the deportees, the number of survivors or the circumstances of their death are also known. Older, frail or prominent Jews and those with special merits in the First World War were deported to the camp known as the "Theresienstadt old age ghetto". Before that, they had to sign home purchase contracts and largely cede their assets. However, this did not protect them from inadequate living conditions and "relocation to Auschwitz ".

From October 15, 1941 to the beginning of November, twenty trains transported around 20,000 Jews from the major cities of Vienna, Prague, Frankfurt am Main , Berlin and Hamburg to Łódź . More than 4,200 of them died in the ghetto by the end of 1942. Another seven transports were directed to Minsk ; of them only five survived the war. Because the ghetto was overcrowded, five deportation trains were forwarded to Kaunas in November 1941 and another ten trains to Riga from the end of November. The Riga ghetto was also overcrowded; it was immediately “cleared” by murdering around 27,500 local Jews. A transport train from Berlin reached Riga prematurely on November 30, 1941; all 1,053 inmates were shot in the Rumbula forest . In Lithuania , too , Einsatzgruppen and their Lithuanian helpers murdered almost 5,000 deportees from Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Breslau and Frankfurt am Main in the Ninth Fort of Kauen in November 1941. This mass shooting is interpreted as the arbitrariness of Friedrich Jeckeln and Karl Jäger , for whom no order had yet been received and which Himmler did not approve.

In January 1942 another nine deportation trains with an average of 1,000 Jews drove to Riga. Between March and October 1942, over 45,000 Jews from the German Reich were deported to transit ghettos on the eastern edge of the Generalgouvernement and to Warsaw . In a “Jewish exchange” - as the perpetrators were called - the local Jews from Lublin were sent to the Belzec extermination camp to make room for the “Reich Jews”.

For the first time in May 1942, and increasingly from mid-June 1942, Jews from Germany were deported to extermination camps either directly or via Theresienstadt. 17 transports between May and September 1942 went to Minsk or immediately to the nearby Maly Trostinez extermination camp . From June 1942 to April 1945, numerous deportation trains had the “old people's ghetto” Theresienstadt as their destination, but “paddock trains” with a few wagons that carried barely more than a hundred frail elderly Jews predominated. In the same period, however, trains also left Theresienstadt several times and brought their human cargo to Treblinka and Auschwitz. 21 passenger cars were ordered for the first two of these trains; they were completely overloaded with more than 2,000 people. In 1942, five large deportation trains drove from Vienna and Berlin to Auschwitz.

Between 1943 and 1945 only the Auschwitz extermination camp and the Theresienstadt concentration camp were chosen as destinations for the deportation trains from the German Reich. The mass deportation of Jewish Germans in whole trains ended at the end of March 1943 with the arrests at work in the factory action . Officially registered there were still 31,897 Jews living in the Reich, including more than 18,500 in Berlin. More than 200 transports followed, often with just a few people. As a rule, these were older Jews who were deported to the “Theresienstadt old age ghetto”. The Reich Ministry of Transport was not responsible for such transports, in which individual through coaches ran along with scheduled trains. From July 1942, transports with 100 victims each from Berlin left Berlin several times a month from the Anhalter Bahnhof via Theresienstadt to the death camps.

In February and March 1945, 2,600 Jewish spouses, who had previously been spared under the protection of a “mixed marriage”, were also deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. This nationwide planned action was canceled in the final phase of the war; almost all of these deportees survived because the war ended.

Deportation trains in the east

In the spring of 1942 the Belzec extermination camp was completed, Sobibor and Treblinka followed in the summer of 1942. The Reichsbahn carried out the transport from the camps and ghettos to the extermination camps with freight cars. Even over long distances, goods wagons were used almost exclusively for deportations in the east - for example from Romania and Hungary. Here reality coincides with the “ collective memory ”, which is determined by iconic photos of overcrowded boxcars.

In September 1942, representatives of the Reichsbahn took part in a “conference on the evacuation of Jews from the General Government and the deportation of the Jews of Romania to the General Government”. A total of 800,000 Jews were to be deported. The chief of the security police and the SD were urgently requested

- two trains per day from Warsaw district to Treblinka,

- one train per day from Radom district to Treblinka,

- one train per day from Krakow district to Belzec and

- one train per day from Lviv district to Belzec.

After the tracks were repaired, three more trains were to run to Sobibor and Belzec every day from November. However, a total of only 22 freight cars were available. Only after the potato harvest would more wagons be available.

The German and Austrian Jews who had previously been deported to the transit camps (“ghettos”) near Lublin were not excluded from these mass murders . The German Jews of four large and several small transports to Warsaw were also included in the extermination campaign. Between Warsaw and the Treblinka extermination camp , over a distance of 80 km, from a technical point of view a "shuttle traffic" was created.

Post-war processes and reappraisal

Deportations were at the beginning and as a conditio sine qua non of the extermination of the German Jews, since those responsible shied away from carrying out the mass murder in Germany themselves.

The deportations only became the focus of German criminal proceedings at a late stage. In thirteen West German proceedings and six East German trials, around 60 higher Gestapo ranks had to answer in court.

Ten of the defendants who were brought to court in East Germany were sentenced to long prison terms. The judges assumed that the illegality of the deportations was obvious and that the defendants had carried out their work out of conviction, indifference or career sake. The trials began much earlier than in the Federal Republic of Germany, but there were deficits in persecution in the GDR and the heads of many Gestapo control centers remained unmolested.

Most of the time, western law enforcement agencies started their investigations late. Offenses such as deprivation of liberty and manslaughter were already time barred . The West German courts acquitted 38 defendants. Nine suspects were convicted, two were sentenced to more than six years' imprisonment and one was sentenced to life imprisonment. Most of the defendants argued that they had the genocide known nothing (cf.. Contemporary knowledge of the Holocaust ), they made a superior orders submitted or protested that they had at the time the illegitimacy not recognize their actions.

The State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Transport, Albert Ganzenmüller , fled the internment camp to Argentina in 1945. His denazification process was delayed; Ganzenmüller returned in 1955 and worked as a transport specialist at Hoesch AG in Dortmund until 1968 . In 1957 the law enforcement agency investigated him; The reason was an incriminating correspondence about "Jewish transports" that was found. The investigations were discontinued several times, but in 1973 they led to the indictment: Ganzenmüller had knowingly assisted the murder. Thus, 28 years after the end of the war, the first proceedings against high-ranking Reichsbahn members took place. There was no conviction; Ganzenmüller was permanently incapable of negotiating.

Anyone who was involved in the deportations in other functions, as an administrative member or mayor, usually remained unmolested and got away with impunity.

The French railway company SNCF got involved in carrying out deportations under the Vichy government . She faced her story with an exhibition, but refused any claims for compensation . For a long time, Deutsche Bahn was reluctant to provide space for a corresponding exhibition or to finance other solutions. Only after the intervention of Federal Transport Minister Wolfgang Tiefensee was the touring exhibition “ Special Trains to Death ” opened in January 2008 at Potsdamer Platz station in Berlin .

On September 29, 2005, the Dutch national railway company, Nederlandse Spoorwegen, apologized for participating in the deportation of Jews.

Memorials, exhibitions

“ Special trains to death ” is the title of a traveling exhibition that recalls the Reichsbahn transports to the National Socialist camps. It was shown in France in 2006 and in 2008 (in a modified form) in Germany in around 10 train stations. The exhibition, conceived by Deutsche Bahn in collaboration with Beate and Serge Klarsfeld together with a citizens' initiative, integrates elements from the exhibition “Enfants juifs déportés de France”, which was shown over three years at the French SNCF train stations.

“ Train of Remembrance ” is the name of a unique “rolling exhibition” on German rails, which in 2007, 2008 and 2009 was dedicated to the deportation of several hundred thousand children from Germany and the rest of Europe on the rail network , with the staff and rolling stock of the former Reichsbahn German concentration and extermination camps. By focusing on a group of victims, the young generation should be able to identify more easily with the victims of the Shoah . The train's journey began on November 9, 2007 in Frankfurt am Main . The date referred to the persecution measures in the German Reich. This was followed by a 3,000-kilometer journey through cities and to the stations of the SS deportations.

The DB company, legal successor to the DR, refers to the permanent exhibition it set up in 2002 on the role of the Reichsbahn in World War II in the DB Museum in Nuremberg (Transport Museum) .

The German Museum of Technology in Berlin has been portraying 12 of Berlin's fates since October 2005 in Lokschuppen 2 as part of a permanent exhibition “'Deportations of Jews' with the Deutsche Reichsbahn 1941–1945”. An old freight wagon for the "transport of cattle and moisture-sensitive objects" is central as an exhibit. So-called “cattle wagons” are also used in other memorials as symbols of deportation and the Holocaust; however, they cannot be considered an authentic relic . Other memorials are the memorial for freight wagons in Hamburg-Winterhude, the memorial at the north train station in Stuttgart, the track 17 memorial at Berlin-Grunewald train station and the deportation memorial in Duisburg main train station .

The subject of deportation is also featured in the award-winning short film Toy Land (2007).

The memorial at the Frankfurt wholesale market hall (at the ECB ) was opened to the public in 2015.

Related topics

- Deportation of Jews from Nuremberg

- Deportation of Jews from France

- Deportation of Jews from Hungary (paragraph in history article)

- Jewish houses and apartments were a pre-form of the ghettos.

- The 1940 Madagascar Plan, which was not implemented, provided for the deportation of four million European Jews to Madagascar .

Dramatization in the film

- The Last Train (2006) , the film by Artur Brauner directed by Joseph Vilsmaier , recreates the fate of the last Jewish Berliners who were deported from platform 17 of the Berlin-Grunewald train station to the Auschwitz concentration camps in April 1943 .

literature

- Hans Günther Adler: The administered person: Studies on the deportation of Jews from Germany. Mohr, Tübingen 1974, ISBN 3-16-835132-6 (comprehensive documentation of the bureaucracy).

- Hans Günther Adler: The hidden truth. Theresienstadt documents. Mohr, Tübingen 1958.

- Christopher Browning : Unleashing the “Final Solution”: National Socialist Jewish Policy 1939–1942. Propylaeen, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-549-07187-6 (chapter 'Deportations from Germany', pp. 537-569).

- Andreas Engwert, Susanne Kill: Special trains to death. The deportations with the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Documentation accompanying the traveling exhibition. Böhlau, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20337-5 .

- Alfred Gottwaldt , Diana Schulle: The "deportations of Jews" from the German Reich, 1941–1945: an annotated chronology. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 and ISBN 978-3-86539-059-2 (data from most of the “Jewish transports” from the “Greater German Reich” are compiled and commented on.).

- Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: “Jews are prohibited from using dining cars”: The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945; Research report. Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 .

- Alfred B. Gottwaldt: Dunning place Moabit freight yard . The deportation of Jews from Berlin. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-95565-054-4 (= Topography of Terror Foundation, Notes, Volume 8.).

- Raul Hilberg : Special trains to Auschwitz. Dumjahn, Mainz 1981, ISBN 3-921426-18-9 .

- Heiner Lichtenstein : With the Reichsbahn to death: mass transports into the Holocaust 1941–1945. Bund, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-7663-0809-2 (partly outdated).

- Albrecht Liess: Paths to Destruction: The Deportation of the Jews from Main Franconia 1941–1943. Accompanying volume for the exhibition of the State Archives Würzburg and the Institute for Contemporary History Munich-Berlin. General Directorate of the Bavarian State Archives, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-921635-77-2 (exact local historical representation of three deportations with photos).

- Roland Maier: The persecution and deportation of the Jewish population. In: Ingrid Bauz, Sigrid Brüggemann, Roland Maier (eds.): The Secret State Police in Württemberg and Hohenzollern. Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 3-89657-138-9 , pp. 259-304.

- Beate Meyer (ed.): The persecution and murder of Hamburg's Jews 1933–1945: history, testimony, memory. Institute for the History of German Jews, Hamburg / State Center for Political Education, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-929728-85-0 (eyewitness reports).

- Birthe Kundrus , Beate Meyer (ed.): The deportation of Jews from Germany: plans - practice - reactions 1938–1945. Wallstein, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-792-6 .

- Kurt Pätzold , Erika Schwarz: “Auschwitz was just a train station for me”. Franz Novak - Adolf Eichmann's transport officer. Metropol, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-926893-22-2 (about Franz Novak ).

- Christiaan F. Rüter : East and West German criminal proceedings against those responsible for the deportation of the Jews. In: Anne Klein , Jürgen Wilhelm (eds.): Nazi injustice before Cologne courts after 1945. Greven, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-7743-0338-X , pp. 45–56.

- Akim Jah: The deportation of the Jews from Berlin. The National Socialist extermination policy and the Grosse Hamburger Strasse assembly camp . be.bra, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-95410-015-6 .

- Herbert Schultheis: Jews in Mainfranken 1933-1945 with special consideration of the deportation of Würzburg Jews. Bad Neustädter contributions to the history and local history of Franconia. Volume 1. Bad Neustadt ad Saale 1980. ISBN 3-9800482-0-9 .

- Pictures and files of the Gestapo Würzburg about the deportations of Jews 1941-1943. Edited by Herbert Schultheis and Isaac E. Wahler. Bad Neustädter contributions to the history and local history of Franconia. Bad Neustadt ad Saale 1980. ISBN 3-9800482-7-6 .

Web links

- Secret express letter dated January 31, 1942 regarding "Evacuation of Jews" pdf

- Deportation notice Hameln 1942

- (wayback archive) US Holocaust MM: Photos of deportation trains ( Memento from May 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Statistics on the Jewish population and deportation

- Federal Archives: Chronology of the deportations from the German Reich

- "Deportations of Jews" with the Deutsche Reichsbahn 1941–1945. Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin , 2005, accessed on November 9, 2009 .

- Website of the "Train of Remembrance"

- 1941: First deportations from northwest Germany. Web project with biographies of the deportees on the History.Aconscious.being site

- yadvashem: The deportation of the Jews from Germany to the East

Individual evidence

- ^ Albrecht Liess: Paths to Destruction: The Deportation of Jews from Main Franconia 1941–1943. Accompanying volume to the exhibition of the State Archives Würzburg and the Institute for Contemporary History Munich-Berlin . Munich 2003, ISBN 3-921635-77-2 , p. 60; see. VEJ 3/223 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 3: German Reich and Protectorate September 1939 - September 1941 (edited by Andrea Löw), Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3- 486-58524-7 , p. 542: On September 18, 1941, Himmler informed us that the Führer wanted the Jews to be deported from the " Old Reich " and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia .

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The annihilation of the European Jews. 1982, p. 287.

- ↑ Heiner Lichtenstein: With the Reichsbahn into death: Mass transports in the Holocaust 1941–1945 . Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-7663-0809-2 , p. 19.

- ↑ Helmut Schwarz: The machinery of death. The Reichsbahn and the final solution to the Jewish question. In: Train of Time - Time of Trains. German Railways 1835–1985. Vol. 2. Berlin (Siedler) 1985, pp. 683-689.

- ↑ on the Deutsche Reichsbahn see: Deutsche Reichsbahn (1920–1945)

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: 'Jews are prohibited from using dining cars': The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945; Research report . Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 , p. 11, 63ff.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The 'logistics of the Holocaust' as a murderous task of the Deutsche Reichsbahn in the European area. In: New Paths in a New Europe Ed. Ralph Roth / Karl Schlögel. Frankfurt / M. 2009, pp. 261-280.

- ↑ Beate Meyer: The persecution and murder of Hamburg's Jews 1933-1945: history, testimony, memory . Ed. By the Inst. For the history of the German. Jews; Hamburg / State Center for Political Education , Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-929728-85-0 , p. 44 f.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt / Diana Schulle: The "Deportations of Jews" from the German Reich 1941-1945. Wiesbaden 2005, p. 146ff. (Doc .: "Guidelines for the technical implementation of the evacuation of Jews in the Generalgouvernement ( Trawniki near Lublin)" of the Reich Security Main Office from January 1942)

- ^ Sources on the history of Thuringia. The Secret State Police in the Nazi Gau Thuringia 1933 - 1945. II half volume, pp. 384 - 386: The “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” / e .: “unknown displaced”. Guideline of the Reich Main Security Office for the Deportation of Jews to Auschwitz (February 20, 1942)

- ↑ s. also: Telegram letter from the Deutsche Reichsbahn dated June 23, 1942 to Gbl West, Gbl. East etc. subject: special trains to transport Jewish workers from France, Belgium and Holland to Auschwitz. Fig. Of the document in: Special trains in the death. The deportations of the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Edited by A. Engwert u. S. Kill. 2nd edition Cologne 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Michael Zimmermann : Regional organization of the deportations of Jews. In: Gerhard Paul, Michael Mallmann (ed.): The Gestapo - Myth and Reality. Unv. Special edition Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-89678-482-X , p. 358.

- ^ HG Adler: The Hidden Truth - Theresienstadt documents. Tübingen 1958, p. 20: Decree of September 7, 1942 regarding relocation instead of evacuation

- ↑ Himmler's instruction of September 18, 1941 (VEJ 3/233) The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (collection of sources), Volume 3: German Reich and Protectorate September 1939 - September 1941 (edited by Andrea Löw ), Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , p. 542.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The Reichsbahn and the Jews 1933–1939 - Anti-Semitism on the railroad in the prewar period . Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86539-254-1 , p. 374.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The Reichsbahn and the Jews 1933 1939… . Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86539-254-1 , p. 363.

- ↑ Seev Goshen: Eichmann and the Nisko-Aktion in October 1939. In: Vierteljahrsheft für Zeitgeschichte 29 (1981), pp. 74-96.

- ↑ VEJ 3/40 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany 1933-1945 (collection of sources) Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , S. 148th

- ↑ The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 . Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , p. 38.

- ^ Robert Kuwałek : The short life 'in the east'. In: Birthe Kundrus, Beate Meyer (ed.): The deportation of the Jews from Germany. Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-792-6 , pp. 112-134; s. a. Document expulsion order (Gestapo Stettin, February 1940) ( Memento of November 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) / for more precise figures see p. Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: The "deportations of Jews" from the German Reich, 1941–1945: an annotated chronology . Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 , p. 34 with note 3.

- ↑ VEJ 3/52 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945 . Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7

- ↑ Beate Meyer: Tödliche Gratwanderung - The Reich Association of Jews in Germany between Hope, Coercion, Assertion and Entanglement (1939–1945). Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0933-3 , pp. 88-91.

- ↑ Numbers 6300 plus 1150 in VEJ 3/113 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , p. 299.

- ↑ Heydrich according to Hitler's permission, cf. VEJ 3/112 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , p. 298.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: “Jews are prohibited from using dining cars”: The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (research report ) Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 , p. 72.

- ↑ Peter Steinbach: The suffering - too heavy and too much. On the significance of the mass deportation of Southwest German Jews . In: Tribüne - magazine for the understanding of Judaism. 49. Vol. 195. 3rd quarter 2010, p. 109–120, here p. 116 on the Internet (PDF; 81 kB).

- ↑ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: The "deportations of Jews" from the German Reich, 1941–1945: an annotated chronology . Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 , pp. 46-51.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen… , p. 45 / VEJ 3/52 in: The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 , Volume 3, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , P. 169 f.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 61/62.

- ↑ Serious estimates amount to 257,000 to 273,000 emigrants: Christoph Franke: The role of foreign exchange offices in the expropriation of the Jews. In: Katharina Stengel (Ed.): The state expropriation of the Jews in National Socialism. Frankfurt a. M. 2007, ISBN 978-3-593-38371-2 , p. 84. In addition to a total of 262,000, the maximum number 352,686 is reported by Beate Meyer: Tödliche Gratwanderung… , Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0933-3 , P. 47 in note 87 This number also in VEJ 3/233 = The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (collection of sources) Volume 3: German Reich and Protectorate September 1939 - September 1941 (edited by Andrea Löw), Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58524-7 , p. 557 as an indication of the Reichsvereinigung. Number 330,000 “plausible” according to Nicolai M. Zimmermann: What happened to the Jews in Germany between 1933 and 1945? In Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 64 (2016), no. 12, p. 1052 f.

- ↑ Wolf Gruner: From collective expulsion to deportation. In: Birthe Kundrus, Beate Meyer (ed.): The deportation of Jews from Germany , Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-792-6 , p. 54 - number 151,000 in VEJ 3/233.

- ^ Nicolai M. Zimmermann: What happened to the Jews in Germany between 1933 and 1945? In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 64 (2016), no. 12, pp. 1048-1052.

- ↑ Wolf Gruner: From collective expulsion to deportation. , P. 57

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Dimension of the genocide. dtv Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-54631-7 , p. 52.

- ↑ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: Juden ist… / research report . Pp. 39, 61, 74.

- ↑ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: Juden ist… research report . P. 89.

- ↑ Alfred B. Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are prohibited from using dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Research report, prepared on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development. Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2007, p. 76

- ↑ Thomas Kuczynski: Serving the regime - not making money. On the participation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn in deportations and forced labor during the Nazi dictatorship. A consideration from an economic point of view. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 57 (2009), no. 6, p. 520 ff .: "In 1942 a total of 20,000 trains a day compared to five trains with forced laborers, prisoners and deportees"

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The German 'Viehwaggon' as a symbolic object in concentration camp memorials , in: Gedenkstättenrundbrief (published by the 'Topography of Terror Foundation'), No. 139 (October 2007), p. 21 ( online ).

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 64 and 331 / Document 6 in: Hans Günther Adler: The secret truth. Theresienstadt documents. Tübingen 1958, p. 1942.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle, Die Judendeportationen … lists around 180 small transports between June 1942 and March 1943 on pp. 447–457 alone.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 287 u. 289; Hans Günther Adler: The administered person: Studies on the deportation of Jews from Germany , Tübingen 1974, ISBN 3-16-835132-6 , p. 449.

- ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: Public Enterprise in the Service of Mass Murder. In: Holocaust and Genocide studies 15 (2001), p. 45.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 324 and 132.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The German 'Viehwaggon' ... , p. 21/22.

- ↑ Kurt Pätzold , Erika Schwarz: Agenda for the murder of Jews: The Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942: A documentation on the organization of the “Final Solution” . Berlin 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The German 'Viehwaggon' ... , p. 24.

- ↑ Gottwaldt / Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 64.

- ↑ so the Gestapo term - see Akin Jah: The Berlin assembly camps in the context of the "Jewish deportations" 1941–1945. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtsforschung 61 (2013), no. 3, p. 211.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen , Susanne Willems (ed.): Everyday rule in the Third Reich . Düsseldorf 1988, pp. 471-473; Printed as a document in: Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: Die Judendeportationen… , p. 56 ff.

- ↑ Facsimile of the guidelines of June 4, 1942 with Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: The "Deportations of Jews" from the German Reich 1941–1945: a commented chronology. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 , pp. 170-177.

- ↑ Printed by Hans Günther Adler: The administered person: Studies on the deportation of Jews from Germany . Tübingen 1974, ISBN 3-16-835132-6 , pp. 554-59.

- ^ Ingrid Bauz, Sigrid Brüggemann, Roland Maier (eds.): The Secret State Police in Württemberg and Hohenzollern, ISBN 3-89657-138-9 , p. 268.

- ↑ Document Würzburg 1941 in: Albrecht Liess: Paths to Destruction ... , p. 81 ff.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen, Susanne Willems (ed.): Everyday rule in the Third Reich . Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-491-33205-2 , pp. 480-482 (leaflet Reichsvereinigung June 1942).

- ↑ Susanne Heim (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 6: German Reich and Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, October 1941 – March 1943. Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-11 -036496-5 , pp. 33-37 as well as doc. VEJ 6/218 and VEJ 6/241

- ↑ For example for Berlin: Akim Jah: The Berlin assembly camps in the context of the “Jewish deportations” 1941–1945 . In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft (1953) Vol. 61, H. 3 (2013), pp. 211-231.

- ↑ Christiane Kuller: First principle: hoarding for financial management '. The exploitation of the property of the deported Nuremberg Jews. In: Birthe Kundrus, Beate Meyer: The deportation of the Jews from Germany. Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-792-6 , p. 165

- ↑ Michael Zimmermann: Regional Organization ... , p. 361.

- ^ Document in: Hans Günther Adler : The secret truth. P. 61/62; quoted in: Walther Hofer: The National Socialism. Documents 1933-1945. FiTb 6084, revised. New edition Frankfurt / M. 1982, ISBN 3-596-26084-1 , pp. 298 f. = [172].

- ↑ Michael Zimmermann: Regional Organization ... , p. 361 with annotation 25

- ↑ Beate Meyer (ed.): The persecution ... , p. 45.

- ↑ Michael Zimmermann: Regional Organization ... , p. 370 f.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: The "Deportations of Jews" from the German Reich ... , Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 , p. 150.

- ↑ Kurt Pätzold, Erika Schwarz: Agenda for the murder of Jews… , p. 87 f.

- ↑ Heiner Lichtenstein: With the Reichsbahn in den Tod ... , pp. 54–59 / reprinted as document VEJ 6/59; Another report is printed as Document VEJ 6/42 in: Susanne Heim (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 6: German Reich and Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia October 1941– March 1943. Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-036496-5 .

- ↑ Information from Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: Die Judendeportationen… .

- ^ Andrej Angrick , Peter Klein: The "Final Solution" in Riga: Exploitation and Destruction 1941–1944 . Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-534-19149-8 , p. 169.

- ^ Christoph Dieckmann: German occupation policy in Lithuania 1941-1944. Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0929-6 , vol. 2, p. 959 and 962.

- ^ Peter Longerich : Politics of Destruction. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-492-03755-0 , p. 487.

- ↑ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: Die Judendeportationen ... , p. 401.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Hitler. Biography. Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-8275-0060-1 , p. 905 (with reference to HG Adler: Der verwalten Mensch. Tübingen 1974, p. 201).

- ↑ Data and number of victims at: Statistics and Deportation of the Jewish Population from the German Reich (at www.statistik-des-holocaust.de)

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The 'logistics of the Holocaust' as a murderous task of the Deutsche Reichsbahn in the European area. In: Ralf Roth, Karl Schlögel (Hrsg.): New ways in a new Europe - history and traffic in the 20th century. Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38900-4 , p. 270.

- ↑ Heiner Lichtenstein: With the Reichsbahn into death ... , p. 62 f.

- ↑ Cf. Christian Frederick Rüter: East and West German criminal proceedings against those responsible for the deportation of the Jews , in: Anne Klein, Jürgen Wilhelm (Ed.): NS - Injustice before Cologne Courts after 1945. Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-7743- 0338-X , p. 45.

- ↑ Christian Frederick Rüter: East and West German criminal proceedings ... , p. 51.

- ↑ amz / AFP : " Compensation suit for deportations finally failed ", Spiegel Online , December 21, 2007; Accessed January 7, 2003.

- ↑ Flyer: Train of Memory (PDF; 290 kB) Accessed January 8, 2008.

- ↑ lw / ddp : “ 'Special trains into death' is shown in the train station ”, Spiegel Online , January 22, 2008.

- ^ Exhibition of the Deutsche Bahn DB Museum Nürnberg (Ed.): In the service of democracy and dictatorship. The Reichsbahn 1920–1945. Catalog for the permanent exhibition in the DB Museum, Nuremberg 2002.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: The German 'Viehwaggon' as a symbolic object in concentration camp memorials, pp. 18–31. In: Memorial circular (published by the 'Topography of Terror Foundation'), No. 139 (October 2007) / on the Internet: [1] .