Holocaust in Lithuania

The Holocaust in Lithuania was a genocide that almost completely killed the Jewish population of Lithuania between 1941 and 1944 . Over 200,000 Jews were murdered mainly by members of the German Einsatzgruppen and their helpers, with numerous Lithuanians taking part in pogroms and the murder of the Jewish population.

background

The First Lithuanian Republic was established in February 1918. In the Polish-Lithuanian War of 1920, she lost the predominantly Polish-inhabited areas of Lithuania around Vilnius to Poland ; Kaunas became the "temporary capital" of Lithuania. At the end of September 1939, the Soviet Union declared Lithuania to be its area of interest in the German-Soviet border and friendship treaty, and immediately handed over the area of Vilnius to Lithuania, but at the same time stationed troops and undermined the sovereignty of the state. In June 1940 the Red Army marched into Lithuania and on August 3, 1940 the country was incorporated into the USSR as the "Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic".

From then on, the NKVD persecuted, imprisoned or abducted people who were accused of counter-revolutionary , anti-Soviet sentiments or of economic sabotage. More than 20,000, according to other information even up to 35,000 Lithuanians were forcibly deported to Siberia between June 14 and 22, 1941 (the day of the German attack on the Soviet Union ) .

Jewish minority

Before 1939 there were 150,000 to 155,000 Jews in Lithuania. Add about 80,000 Jews from Vilnius (city and administrative area) who came to Lithuania after the area was ceded to the Soviet Union in October 1939. About 10,000 Jews later managed to flee to the Soviet Union.

Lithuanian nationalists defined their national identity through their language; however, the everyday language of the Jewish minority was Yiddish , regionally also Polish or Russian . According to historians , the political conditions between 1938 and June 1941 caused "severe shocks" or even a "complete disruption" of Lithuanian society and intensified anti-Semitism to the point of violent forms. For example, the equality of treatment decreed by the Soviet Union in the filling of offices led to the escalation of hostile feelings. In the perception of Lithuanians, the Jews were privileged by the Soviet Union, and they were also accused of collaboration . Their involvement and influence in the Communist Party have also been greatly overestimated. Several thousand Jews and Poles were among the "anti-Soviet elements" who were abducted just before the German invasion.

course

Shortly after the German attack on the Soviet Union (see: Hitler-Stalin Pact ), the Wehrmacht invaded Lithuania on June 22, 1941. Many Lithuanians saw this as a liberation from the Soviet Union's Red Army . Immediately after the invasion, there were violent attacks on Jewish citizens, tolerated by the Germans and in some cases secretly initiated, by Lithuanians with a patriotic nationality. The number of Jews killed in the process is estimated to be at least four thousand.

German military personnel who were eyewitnesses to the murder of Jews in Kaunas, the Ponary massacre or Vilna, did not intervene. When the commander of the Rear Army Area North , Franz von Roques , reported to his superior Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb about the mass shootings in Kaunas, he was recommended to exercise restraint. Roques himself said that the Jewish question could not be solved in this way, but that the sterilization of all male Jews was the safest solution.

The German leadership had already planned a civil administration for the area to be conquered before the start of the war, which was subordinated to Hinrich Lohse as Reichskommissariat Ostland . According to a draft of "Preliminary Guidelines for the Treatment of Jewish Citizens", the rural area should be "cleared" of Jews and anti-Jewish measures taken. The head of Einsatzgruppe A , Walter Stahlecker , objected to these measures on August 6, 1941, because they did not take into account the “new possibilities for settling the Jewish question”. He suggested an "almost 100% immediate cleansing of the entire eastern region", the "prevention of the multiplication of the Jews" and a ghettoization as "an essential relief of the later collected evacuation to a non-European Jewish reservation". In fact, a little later, members of his task force began a planned mass murder: On August 15 and 16, 1941, SS Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann had 3,200 Jews shot, including numerous women and children. Heinrich Himmler's instructions were probably given as early as the end of July 1941.

The German civil servants did not just approve of the murders. Like Wehrmacht officers, they themselves initiated massacres. In the first half of August 1941, district and area commissioners repeatedly called for “unproductive” Jews to be killed. In Lithuania the Jews were sent to about 100 ghettos and camps. In contrast to the carefully screened Jewish residential areas in the larger cities, which were planned for a longer period of time, the smaller ghettos in the countryside were often only synagogues or barns, in which the Jews were often locked up under adverse living conditions and without adequate supplies. As a self-inflicted consequence, infectious diseases spread among the detainees; In some cases, the risk of epidemics served as a pretext for having these Jews killed by the Hamann Roll Command.

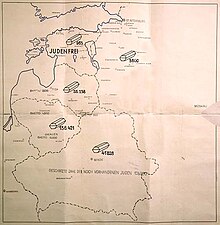

The downfall of the Lithuanian Jews took place until the end of 1941. Never before had so many Lithuanian Jews died in such a short time. About 80,000 Jews had been killed by October. In the report named after him, SS leader Karl Jäger listed the exact dates of the day, crime scenes and the number of murder victims. By December 1, 1941, 137,346 people had been " executed "; This number does not include the Jews who had been murdered by Einsatzkommando 2 in northwestern Lithuania by October. In the minutes of the Wannsee Conference , which took place on January 20, 1942, the number of Jews remaining in Lithuania is put at 34,000.

At the end of 1941, only 43,000 of the previously 215,000 Jews were still living in Lithuania, including the Vilna area. The majority of Jews in Lithuania did not move into urban ghettos, as in neighboring Latvia, for example, and were not deported to concentration camps , but instead were brought together in temporary collection points near their places of residence and soon afterwards shot at excavated pits. The largest "actions" (massacres) of this extermination were committed in the Ninth Fort near Kauen and in the forest of Aukštieji Paneriai south of Vilnius .

In 1942 a second phase of the killings began. The surviving Jews served the war economy as slave labor . The Wehrmacht built the Kauen concentration camp , the Vilna and Schaulen ghetto and several smaller ghettos for the approximately 43,000 "able-bodied" Jewish forced laborers and their relatives . In the third phase of the Holocaust in Lithuania from April 1943 to July 1944, the occupiers dissolved the ghettos and camps and killed the remaining Jews from Kauen and Schaulen.

collaboration

The Red Army occupied Lithuania militarily in 1940. Many Lithuanians saw liberators in the German troops that arrived on June 22, 1941. The German authorities granted the government apparent independence for the first few days. On August 5, the occupiers dissolved this provisional government ( Laikinoji Vyriausybė ). The Prime Minister Kazys Škirpa , in exile in Berlin , was placed under house arrest by the National Socialists and later, like some other members of the provisional government, deported to concentration camps.

During the march in, SS Brigadefuhrer Franz Walter Stahlecker found it "surprisingly not easy at first to start a large-scale pogrom there [in Kovno / Kaunas]". In his report of October 15, 1942, it goes on to say that, with the help of a Lithuanian partisan group, it was finally possible to trigger a pogrom, "without any outside German commission or suggestion becoming apparent." A marauding group of militant Lithuanians under the leadership von Algirdas Klimaitis carried out the first pogrom in Kaunas on the night of June 25th to 26th, 1941, burned down a Jewish residential area with 60 houses, killing 1,500 Jews and a further 2,300 in the following nights.

On June 24, 1941, the German secret and criminal police installed the Lithuanian secret police ( Saugumo policija ). It too worked into the hands of the occupiers during the Holocaust. Some Nazi functionaries rated the zeal of the Saugumo higher than that of the Gestapo . The most devastating effect among the anti-Semitic Lithuanian forces had the special detachment Ypatingasis būrys from the Vilnius area, which killed thousands of Jews ( Ponary massacre ). The Lithuanian Workers Guard also participated in the Holocaust. Many Lithuanian supporters of the German police came from the fascist organization Iron Wolf . The newspaper Naujoji Lietuva (The New Lithuania) wrote in its editorial on July 4, 1941: “The greatest enemy of Lithuania and other nations was - and in some places still is - the Jew. ... A New Lithuania, which joins the New Europe of Adolf Hitler's, must be free of Jews. "

The local population worked with the occupiers to kill the Jews with preparatory measures and logistics. Even if not all Lithuanian citizens approved of the Holocaust and many even risked their lives by hiding Jews, the high level of collaboration with the German occupiers is a characteristic of the Holocaust in Lithuania. With a population of just under three million, around 80% of whom were ethnic Lithuanians, tens of thousands actively participated in the killings of the Jews, only a few hundred resisted, including many citizens of the Polish minority in Lithuania.

Interpretations and processing

In Lithuania

Some historians see the Holocaust in Lithuania as the earliest expression of the so-called " final solution to the Jewish question " and thus set the beginning of the Holocaust in the summer of 1941 in Lithuania. Wolfram Wette interprets this part as the “ overture ” of the genocide before its mechanization through the gas chambers and high-performance crematoria of the stationary death factories . There was controversy as to whether and when the Einsatzgruppen received an express order to murder all Jews - men, women and children - in the conquered areas. In the meantime, it can be proven that the murder action took more and more groups of victims over the course of weeks. The initiative shifted from a hierarchical chain of command to the perpetrators on site, who explored the scope for action granted to them. Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer use the statements of two uninvolved German Wehrmacht members from Wilna to show that the mass murder did not appear to them as unjust or immoral in the "frame of reference" found.

Helmut Krausnick describes it as "one of the most embarrassing chapters in German military history" and a violation of the most elementary duties of an occupation force that the German Wehrmacht did not intervene when Lithuanian perpetrators killed hundreds of Jews. Wolfram Wette also sees the continued inaction of the Wehrmacht officers, through which the action of the Einsatzkommandos and their Lithuanian murder helpers was covered, as a “precedent” that marked the way forward.

Most of the organization, the preparations for the murder and the shootings were carried out by willing Lithuanian helpers. Not only Lithuanian auxiliary police battalions (TDA) as “direct perpetrators”, but also local helpers were involved through administrative preparation and personal support. Historians refer to sources such as the Jäger report and unequivocally emphasize "the clear and exclusively German responsibility". Without racial and ideological guidelines, without "the German initiative, without the German groups of perpetrators, the Holocaust would not have come about in Lithuania." Task Force 3 is emphasized as the "primary force in the organization of the murder".

For political reasons, the Soviet Union stopped coming to terms with the murder of Jews in the Baltic States after the Second World War . The memorial plaques only mentioned the suffering of the “Soviet citizens” or “local citizens” under the occupation of the National Socialist German Reich , but not the Jews in particular. Nazi collaborators in crimes against Jews were generally not punished or only punished slightly.

Since the Soviet Union did not allow any public remembrance of the Holocaust (or only in the formulas of the prevailing ideology), it was primarily Lithuanian writers in exile who made the Holocaust an issue in their homeland, above all the poet Algimantas Mackus (1932-1964 ). In his novella Izaokas, Antanas Škėma (1910–1961) took up the motifs of the sacrifice of Isaac in order to put into words the impossibility of "understanding" the Holocaust.

Only since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the restoration of Lithuania's independence in 1990 has a nationwide discussion about coming to terms with the Holocaust started. In the foreground of perception, however, is one's own victim role during the “Russian years” 1940–1941 and 1944–1989. Lithuania was the first part of the former Soviet Union to include the protection of Holocaust sites in its constitution after independence . In 1995, Lithuanian President Algirdas Brazauskas made an official apology to the Jewish people in front of the Israeli parliament for Lithuania's involvement in the Holocaust. The Simon Wiesenthal Center criticized the slow process and accused the Lithuanian authorities of not bringing war criminals to justice.

In 2000 the “House of Remembrance” ( Atminties namai ) was opened in Vilnius , the first museum in Lithuania in memory of the Holocaust. It was created thanks to the private initiative of a group of intellectuals, including the historian and film critic Linas Vildžiūnas, the journalists Algimantas Cekuolis and Rimvydas Valatka, the theologian Tomas Sernas, the theater critic Irena Veisaite and the screenwriter Pranas Morkus. On August 30, 2016, Stolpersteine were laid for the first time in Lithuania to commemorate the victims of the Nazi regime and the Lithuanian pogroms.

Criminal trials before German courts

In the late 1950s, the federal judiciary began to deal with the crimes of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In the so-called Ulmer Einsatzgruppen Trial in 1958, ten participants in the Holocaust in Lithuania were sentenced to prison terms, including the SS standard leader Hans-Joachim Böhme , who went into hiding after the war, for aiding and abetting the murder of Jews in 3,907 cases.

In April 1961 five perpetrators came to court in Aurich , including the Borkum doctor Werner Scheu and the riding instructor Karl Struve , both of whom were involved in massacres in Lithuania as SS leaders. Both received mild prison sentences which, after a revision three years later, were increased to ten and nine years in prison , respectively. Further processes followed, including a. in September 1961 in Dortmund against Gestapo members Alfred Krumbach , Wilhelm Gerke and Hermann-Ernst Jahr . After the war, Krumbach was an official of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution and appeared as a witness in the Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial. There he was identified as the perpetrator by other witnesses and arrested in the courtroom. Before the jury court in Dortmund he received four years and six months imprisonment for participating in the killing of 827 people in Lithuania.

See also

- Kailis Fur Factory , Vilnius

- Deployment of Helmut Rauca in Lithuania

- Holocaust in Estonia

- Holocaust in Poland

literature

- Yitzhak Arad : The "Final Solution" in Lithuania in the Light of German Documentation. In: Michael R. Marrus : The Nazi Holocaust: historical articles of the destruction of European Jews. 4. The "Final Solution" outside Germany. Vol. 2, Meckler, Westport 1989, pp. 737-776 (first Yad Vashem Studies, 1976).

- Vincas Bartusevicius, Joachim Tauber, Wolfram Wette (Hrsg.): Holocaust in Lithuania . War, murder of Jews and collaboration in 1941. Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-13902-5 .

- Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss (ed.): Murder of Jews in Lithuania . Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 .

- Arūnas Bubnys, D. Kuodytė: The Holocaust in Lithuania between 1941 and 1944 . Ed .: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. 2005, ISBN 9986-757-66-5 .

- Alfonsas Eidintas: Jews, Lithuanians and the Holocaust . Taurapolis, Vilnius 2012, ISBN 978-6-09953600-2 .

- Karl Heinz Gräfe: From the thunder cross to the swastika. The Baltic States between dictatorship and occupation . Edition Organon, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-931034-11-5 .

- Milda Jakulytė-Vasil (Ed.): Lithuanian Holocaust atlas . Valstybinis Vilniaus Gaono žydų muziejus, 2011, ISBN 978-9955-767-14-5 .

- Rose Lerer-Cohen, Saul Issroff: The Holocaust in Lithuania 1941-1945 . A Book of Remembrance. Gefen, 2002, ISBN 965-229-280-X .

- Yosif Levinson (Ed.): The Shoah (Holocaust) in Lithuania . Valstybinis Vilniaus Gaono žydų muziejus, 2006, ISBN 5-415-01902-2 .

- Ephraim Oshry: Churbn Lite . New York / Montreal 1951, OCLC 163050517 .

- Ephraim Oshry: The Annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry . Judaica Press, New York 1995, ISBN 1-880582-18-X .

- Saulius Sužiedėlis, Christoph Dieckmann : Lietuvos žydų persekiojimas ir masinės žudynės 1941 m. vasarą ir rudienị. Šaltiniai ir analizė (= The persecution and the mass murder of the Lithuanian Jews in the summer and autumn of 1941. Sources and analyzes). Margi Raštai, Vilnius 2006 (Lithuanian) [the most comprehensive source edition on the subject to date].

- Robert van Voren (Ed.): Undigested Past . The Holocaust in Lithuania. Rodopi, Amsterdam / New York 2011, ISBN 978-90-420-3371-9 .

Web links

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Encyclopedia: LITHUANIA

- Holokausto Lietuvoje Atlasas / Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania

- The Holocaust in Lithuania - Materials in English for Holocaust Studies Educators and Students - Collection of materials compiled by Dovid Katz

- Map of the Jewish Communities of Lithuania: Links to their Holocaust Fate

- The Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania

- Ekaterina Makhotina: Our Own - The Holocaust Debate in Lithuania

- www.alles-ueber-litauen.de: Lietuki's garage murders in 1941 . Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- www.alles-ueber-litauen.de Eyewitnesses to the pogroms at the Lietukis garage yard Kaunas in 1941 . Retrieved December 13, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ^ Jewish population of Lithuania: 215,000 for Lithuania including the Wilna area In: Bert Hoppe , Hiltrud Glass (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I - Occupied Soviet territories under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , p. 56. / Jewish population 250,000 In: Michael MacQueen: Mass destruction in context: perpetrators and conditions of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 15.

- ^ Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger - Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 60.

- ^ Michael MacQueen: Poles, Lithuanians, Jews and Germans in Wilna 1939–1944. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 61.

- ↑ Number 155,000 in: Bert Hoppe, Hiltrud Glass (arr.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. (Source collection) Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I - Occupied Soviet areas under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , p. 50.

- ↑ Numbers in: Michael MacQueen: Mass destruction in context: perpetrators and conditions of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 15 with note 1.

- ^ Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 54.

- ^ Michael MacQueen: Mass extermination in context: perpetrators and conditions of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 16f.

- ^ Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 57ff: 'The explosive domestic political power of the Russian year'.

- ↑ 4,000 Jews killed according to Ernst Klee, Willi Dreßen, Volker Rieß: “Nice times”: murder of Jews from the perspective of the perpetrators and onlookers. Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-10-039304-X , p. 59 / "probably 6000" In: Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 70.

- ↑ Ernst Klee , Willi Dreßen , Volker Rieß: "Schöne Zeiten": Jewish murder from the point of view of the perpetrators and onlookers. Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-10-039304-X , pp. 31-51 (transcribed complete print version).

- ↑ Helmut Krausnick : Hitler's Einsatzgruppen - The Troop of the Weltanschauung War 1938–1942. Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24344-0 , p. 181.

- ↑ a b Bert Hoppe, Hiltrud Glass (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (collection of sources) Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I - Occupied Soviet areas under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , p. 53.

- ↑ Document VEJ 7/181, there S. 515th

- ↑ a b Bert Hoppe, Hiltrud Glass (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (collection of sources) Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I - Occupied Soviet areas under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , p. 54.

- ↑ VEJ 7/187 - The head of the Lithuanian police department asks Hamann on August 25, 1941 to murder the 493 Jews held in Prienai .

- ↑ Arūnas Bubnys: Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Their Results. In: Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas: The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi, 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4 , Google Print, p. 219.

- ^ A b Dina Porat : The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects. In: David Cesarani: The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-15232-1 , Google Print, p. 161.

- ↑ a b c d e Michael MacQueen: The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Volume 12, Number 1, 1998, pp. 27-48, eds.oxfordjournals.org

- ↑ Jäger report in: Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, Volker Riess: "Schöne Zeiten": Jewish murder from the perspective of the perpetrators and onlookers. Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-10-039304-X , pp. 52-62 / as a facsimile from Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , appendix p. 235ff.

- ↑ On the number 137,346 of the Jäger report: 12,600 were murdered outside of Lithuania (Estonia, Latvia, Belarus) ... Jäger does not list the Jews who were killed in northwestern Lithuania from EK 2 to October 1941 (estimated 30,000). The mentioned number of surviving 39,500 working Jews would have to be supplemented by numerous illegal, unregistered Jews. See: Michael MacQueen: Mass Destruction in Context: Perpetrators and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 15 with notes 1 and 2.

- ↑ Bert Hoppe, Hiltrud Glass (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 (source collection) Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I - Occupied Soviet areas under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , p. 56.

- ↑ a b Śledztwo w sprawie masowych zabójstw Polaków w latach 1941-1944 w Ponarach koło Vilnius dokonanych przez funkcjonariuszy policji niemieckiej i kolaboracyjnej policji litewskiej ( Memento of the original on 17 October 2007 at the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link is automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Investigation of mass murders of Poles in the years 1941-1944 in Ponary near Wilno by functionaries of German police and Lithuanian collaborating police). Institute of National Remembrance documents from 2003 on the ongoing investigation. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ↑ a b Czesław Michalski: Ponary - Golgota Wileńszczyzny. ( Memento of the original from December 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Ponary - the Golgotha of Wilno Region). Book nº 5, winter 2000-2001, a publication of the Academy of Pedagogy in Kraków . Last accessed on 10 February 2007.

- ↑ Arūnas Bubnys: Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Their Results. In: Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas: The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi, 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4 , Google Print, p. 215.

- ↑ See Jäger report

- ↑ Timm C. Richter (Ed.): War and crime. Situation and intention: case studies. Munich 2006, ISBN 3-89975-080-2 , p. 53 ff.

- ↑ Arūnas Bubnys: Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Their Results. In: Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas: The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi, 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4 , Google Print, pp. 205-206.

- ↑ see also the Lithuanian Activist Front , which promoted Lithuania's independence from exile in Berlin

- ^ Document L-180 (Einsatzgruppe A - general report up to October 15, 1941) In: IMT: The Nuremberg Trial against the Main War Criminals ... fotomech. Emphasis. Munich 1989, Volume 37, ISBN 3-7735-2527-3 , p. 670ff, here p. 682.

- ↑ IMT: The Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals ... fotomech. Emphasis. Munich 1989, Volume 37, ISBN 3-7735-2527-3 , p. 682 / Partial reprint also in: Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, Volker Riess: "Schöne Zeiten": Jewish murder from the point of view of the perpetrators and onlookers. Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-10-039304-X , p. 32f.

- ↑ a b Arūnas Bubnys: Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija (1941-1944) (German and Lithuanian security police: 1941-1944) . Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras, Vilnius 2004 ( online [accessed June 9, 2006]).

- ^ Dina Porat: The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects. In: David Cesarani: The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-15232-1 , Google Print, p. 165.

- ↑ a b c d Dina Porat: The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects. In: David Cesarani: The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-15232-1 , Google Print, p. 162.

- ↑ Quoted from Tomas Venclova : A Fifth Year of Independence. Lithuania, 1922 and 1994. In: East European Politics and Societies. Vol. 9, 1995, pp. 344-367, quoted p. 365.

- ↑ a b Arūnas Bubnys: Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of the Major Stages and Their Results. In: Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas: The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi, 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4 , Google Print, p. 214.

- ^ A b Tadeusz Piotrowski : Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company, 1997, ISBN 0-7864-0371-3 , Google Print, pp. 175-176.

- ^ David J. Smith: The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-28580-1 , Google Print, p. 9.

- ↑ Righteous Among the Nations ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b NCSJ Country Report: Lithuania ( Memento of 30 April 2002 in the Internet Archive ). Last accessed on 13 March 2007.

- ^ Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 11.

- ↑ Vincas Bartusevicius, Joachim Tauber, Wolfram Wette (ed.): Holocaust in Lithuania. War, murder of Jews and collaboration in 1941. Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-13902-5 , p. 5/6 (chapter 'Lithuania 1941 in the light of research').

- ↑ Sönke Neitzel, Harald Welzer: Soldiers - Protocols of fighting, killing and dying. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-089434-2 , pp. 162-166.

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. The troops of the Weltanschauung war 1938–1942. Through Edition. Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24344-0 , p. 179.

- ^ Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 77.

- ↑ Christoph Dieckmann : German and Lithuanian interests ... In: Vincas Bartusevicius et al. (Ed.): Holocaust in Lithuania ... Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-13902-5 , p. 7.

- ^ Michael MacQueen: Mass extermination in context: perpetrators and conditions of the Holocaust in Lithuania. In: Wolfgang Benz, Marion Neiss: Judenmord in Lithuania. Studies and documents. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-932482-23-9 , p. 16.

- ^ A b c Dov Levin: The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews in Lithuania. Berghahn Books, 2000, ISBN 965-308-084-9 , Google Print, pp. 240-241.

- ↑ Rimvydas Šiljaboris: Antanas Skema - the Tragedy of Creative Consciousness. In: Ders: Perfection of Exile. Fourteen Contemporary Lithuanian Writers . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1970, pp. 94-111.

- ↑ Rimvydas Siljaboris: Algimantas Mackus - the Perfection of Exile. In: Ders: Perfection of Exile. Fourteen Contemporary Lithuanian Writers . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1970, pp. 184-213.

- ^ Rūta Eidukevičienė: Lithuanian-Jewish Relations. Motives of guilt in the Lithuanian literature of the 20th century (based on the story "Hering" by Vincas Kreve and the novella "Isaak" by Antanas Škema). In: Rūta Eidukevičienė, Monika Bukantaitė-Klees (eds.): From Kaunas to Klaipeda. German-Jewish-Lithuanian life along the Memel . Litblockín, Fernwald 2007, ISBN 978-3-932289-95-1 , pp. 187-204.

- ↑ Anti-Soviet impressions often predominate here. See: Daniel J. Walkowitz, Lisa Maya Knauer: Memory and the Impact of Political Transformation in Public Space. Duke University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8223-3364-3 , Google Print, p. 188.

- ↑ Ralph Giordano In: Wolfram Wette: Karl Jäger. Murderer of the Lithuanian Jews. Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19064-5 , p. 16.

- ↑ Ellen Cassedy: We are all here. Facing History in Lithuania. In: Bridges. A Jewish Feminist Journal , ISSN 1558-9552 , Vol. 12 (2007), No. 2, pp. 77-85, here p. 80.

- ↑ Can Lithuania face its Holocaust past? ( Memento of the original from October 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Efraim Zuroff , Director of the Wiesenthal Center , Jerusalem , excerpts from lecture at the conference on "Litvaks in the World," August 28, 2001.

- ^ Leonidas Donskis: The Vanished World of the Litvaks. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research , Vol. 54 (2005), pp. 81–85, here p. 82.

- ↑ Chronicle , accessed on stolpersteine.eu on September 6, 2016.

- ↑ The Six Jurors and the Naumiestis Massacre. In: Der Spiegel . 39/1965.

- ↑ Irene Sagel-Grande et al. (Ed.): Justice and Nazi crimes . Volume XIX, Amsterdam 1978, pp. 1-35.