Economy under National Socialism

The development of the economy under the Nazi regime from Adolf Hitler's " seizure of power " in 1933 to the end of the Second World War in 1945 is described as the economy under National Socialism . From 1933 the Nazi regime tried to vitalize the German economy and to solve the framework conditions of the Versailles Treaty . In the mid-1930s, the self-sufficiency of the economy in the German Reich was proclaimed by the Nazi leadership, but a war economy was being prepared in the background with the involvement of the army and business representatives. The initially unsound, later criminal monetary policy led to an enormous state deficit before the war began, which the Nazi state tried to counter with coercive regulatory measures and uncovered money creation by the Reichsbank. In the course of the war, the resources of the conquered areas were systematically exploited through robbery, forced labor , occupation taxes and requisitions .

Prehistory to the seizure of power

World economic crisis and inflation in the Weimar Republic

The Treaty of Versailles stipulated the separation of territories, which worsened the possibilities of self-sufficiency within the narrowed borders with simultaneous population growth. The loss corresponded to 75% of the German iron ore production, 26% of the lead production and 7% of the industrial enterprises. Furthermore, the agricultural surplus areas West Prussia and Posen and all colonial areas were missing . As long as world trade was intact, the demand for agricultural and production goods could be balanced by imports . The global economic crisis that broke out in October 1929 resulted in a collapse of international trade in addition to the withdrawal of foreign bonds and credits.

It is true that imports fell faster than exports and thus led to a short-term positive foreign trade balance , which also contributed to deflation . But the entire volume of world trade dwindled sharply. Falling world trade and the resulting decline in exports resulted in an increase in unemployment . The resulting decline in purchasing power led to a decline in domestic demand, while a falling volume of domestic trade led to more unemployment. This cycle was accelerated by deflation, as it was effectively a real wage increase and created additional unemployment.

From August 1932, the government under Franz von Papen tried to curb unemployment by motivating companies to invest and gain additional employment. To this end, the entrepreneurs were rewarded with tax vouchers on the one hand when they paid their taxes, and on the other hand and additionally if they increased their staff (this second pillar of motivating entrepreneurs through tax vouchers was hardly used by the entrepreneurs). The stimulus for the economy was initially weak and the hoped-for economic recovery has not yet been achieved. It was not until the following government, Schleicher, that public employment programs were enacted in December 1932 . Unemployment did not rise any further from August 1932 (six million registered unemployed), began to decline slightly after the announcement of the " Papen Plan " (ordinance to stimulate the economy of September 4, 1932) and remained until the end of 1934 (still without Armaments expenditure) halved. The Reinhardt program launched by the Reich government from 1932 onwards also made a contribution , which after the seizure of power fully developed its powers to combat unemployment, albeit de facto a continuation of the Weimar tax policy from which the National Socialists profited.

Economic concepts of the "reformers" and the NSDAP

A diverse group of people from business, finance, science and the press reacted to the negative effects of the global economic crisis with the development and presentation of national concepts.

The personalities referred to here as reformers saw the self-regulating, liberal concept of the world economy based only on supply and demand as a failure.

The demand for self-sufficiency to detach itself from future trouble spots became increasingly important. In doing so, however, the scope of action should be expanded beyond the existing borders of the empire. World-wide, demarcated trading blocs crystallized, whereby England and France formed their own blocs with their colonies. A connection with the Baltic states , Austria , Eastern Europe and the Balkans made sense for the concept of “reformers” . This area has been called Intermediate Europe with different variations . Within this area, agricultural products, raw materials and industrial goods should be exchanged duty-free, and production should be controlled by the state. Germany should be given supremacy. The world economy should be replaced by a large-scale economy .

This tendency played into the hands of the NSDAP , which had no powerful economic concepts before the global economic crisis. The central idea of a living space ideology by Adolf Hitler could be fitted into the theory of the large-scale economy. Autarky became a catchphrase for the economic competence of the NSDAP, which became the second largest party in the Reichstag elections in September 1930. The rise of the NSDAP went hand in hand with the worsening economic situation in Germany.

In the 1930s the real economic problems of the Great Depression were generally present. The National Socialists saw the economic order not only as in need of reform. They generally denied that a functioning economy would lead to increased prosperity for all nations through the international division of labor and technical and organizational progress. Instead, they saw the economy as a Malthusian zero-sum game in which a people can only get richer by taking away a corresponding amount from other peoples or ethnic groups. This worldview was paired with extreme racism, according to which “inferior races” would live parasitically from their “host people”. According to this worldview, the solution to all economic problems lay in the murder of Jews and "Gypsies" and in the conquest of new living space in the east .

Between 1940 and 1942, in the course of the occupation of Poland and the Soviet Union, the " General Plan East " for the colonization of Eastern Europe was developed. This was based on the SS settlement policy with the aim of settling farmers from the Greater German Reich in the conquered eastern areas, forcing the ancestral population to do forced labor or extermination and exploiting raw materials. Supplementing the European large-scale economy with an overseas colonial economy, based on the model of the imperial German colonial empire before 1918, was considered, but not implemented due to the failure of the colonial plans.

Ideological approaches: military economy, living space and self-sufficiency

The term "military economy" means "[...] the organization of the economy in peacetime for war from a military point of view". A few days after Adolf Hitler took office, it was made clear that not only job creation programs, which were budgeted at 3.1 billion Reichsmarks until the end of 1933 , should overcome the economic crisis. An expansion of the territorial base of the Reich according to racial and power-political aspects was part of the ideological concept of the NSDAP. The establishment of the Wehrmacht was necessary for the violent territorial expansion. The realization of the habitat ideology (see blood and soil ideology ) and the self-sufficiency program required targeted and efficient use of state funds. Military economists from various disciplines, such as the military, journalism and economics, agreed on the needs of the economy in peacetime. These were among others:

- Determination of the raw material requirements for the overall economy consisting of the armaments industry and civil industry

- Provision of fuel

- Adaptation of the traffic system to future military conditions

- Regulation of the financing of indirect and direct armaments.

The conservative President of the Reichsbank Hjalmar Schacht , Reich Minister of Economics from October 1934, summarized the measures of the military economy as a new plan . To this day it is controversial to what extent the leaders of the economy wanted to use Hitler for their own purposes, or to what extent they were used by Hitler himself. Not every industry - and within one branch of industry not every company - had the same attitude towards the ideas of autarky and militarization.

Measures and instruments after the seizure of power

Above all, the regime was able to record the rapid reduction in unemployment in the first few years. The world economy had bottomed out as early as 1932, and a new economic upswing was in sight. But Hitler knew very well that the success of his government would be measured by its ability to reduce the disastrously high number of five million unemployed (September 1932).

Road construction

In the cabinet, he urged rapid, state-funded work programs, most of which had already been initiated by the Schleicher government in 1929, such as the contract to build a Reichsautobahn (road and bridge construction program and the promotion of the vehicle industry). The technical director of Sager & Woerner , Fritz Todt , was the organizer and chief planner of the Reichsautobahn construction . After Hitler himself broke the first sod on September 23, 1933 with a great deal of propaganda, construction began in the spring of 1934 with 15,000 workers. The maximum number was reached in 1936 with 125,000 employees, when unemployment had already fallen significantly. From an economic point of view, the construction of the autobahn did not provide any lasting impetus for employment policy, but with its aura of dynamism, bold planning and modernity, the autobahns gave the regime a public success. The military-strategic importance of the Reichsautobahn has to be put into perspective. Although this was accompanied by broad motorization in Germany, which subsequently made it possible for many people to be trained as drivers in peacetime, the Reichsautobahn were of little importance for the transport of heavy weapons and troops to the future war zones. Mainly trains and horses were used for this. However, the road construction program was extremely effective in creating employment for the difficult-to-place group of untrained workers. Significantly more labor was required in the areas of military vehicle construction, shipbuilding and aircraft construction, which mainly produce armaments.

housing

The state work programs of the first few years also included housing construction, the investment of which tripled within a year. By the end of 1934, government funds for job creation measures reached over five billion Reichsmarks, and by 1935 they had risen to 6.2 billion. In fact, the number of unemployed fell to 2.7 million a year after the seizure of power, was only 1.6 million in 1936 and remained below one million in 1937.

Arms business

By far the greatest role in reducing unemployment was played by an "arms boom".

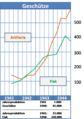

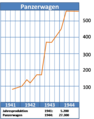

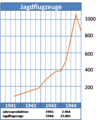

The introduction of compulsory military service on March 16, 1935 led to an increase in the number of troops from around 100,000 to around one million soldiers at the beginning of the war and also contributed to reducing unemployment. At the same time, the armaments investments massively funded by the state with several billions created new jobs in industry. Aircraft production experienced an unprecedented increase from just under 4,000 employees in January 1933 to 54,000 two years later and almost 240,000 employees in spring 1938.

Significantly, the Nazi regime kept the unemployment insurance contribution rate at 6.5 percent of wages, despite full employment, and put these additional billions into arms production. The total assets of the social security funds doubled from 4.6 billion Reichsmarks in 1932 to 10.5 billion in 1939, whereby these monies did not benefit the employees as performance improvements, but rather served the Reich budget as a loan to finance armaments expenditure.

Until 1939 the Nazi state spent 62 billion Reichsmarks on it. This corresponded to a share of the gross national product of 23 percent. In 1933 the proportion was 1.5 percent. Right from the start, the new government pushed for armament. 35 billion Reichsmarks were to be made available for armaments spending over the next eight years - an immense sum when you consider that the total national income of the German Reich in 1933 was around 43 billion Reichsmarks.

This money was raised less through taxes or other income, but mostly through government debt. At the same time as the rearmament program, the decision was made in June 1933 to suspend foreign debt payments for the time being. This unilateral debt moratorium brought the German Reich into disrepute on the international financial markets and at the same time indicated that the new German government no longer felt bound by international treaties. Instead, the Nazi leadership relied on a policy of self-sufficiency, although the Reich continued to rely on imports of raw materials and food and urgently needed foreign currency for armaments production. Reichsbank chief Hjalmar Schacht in particular tried to raise money with unsound measures, but repeatedly hit the limits of the capital markets. Ultimately, as the British economic historian Adam Tooze has described, the Nazi leadership calculated with the intended war in order to then restore the broken German state finances by plundering conquered Europe.

Harmonization of the workforce

The integration of the workforce was initially a problem. To a large extent, the workers were still quite aloof from National Socialism. In the works council elections in March and April 1933, the representatives of the free trade unions still received almost three quarters of the votes, whereas the National Socialist Works Cell Organization (NSBO) only got a good eleven percent of the vote despite seizing power. At the beginning of April 1933, unions and works councils were "brought into line". In order not to allow a power vacuum to develop in the factories and to absorb the organized workforce after the unions had been smashed, the German Labor Front (DAF) was founded under Robert Ley in May 1933 , which took over the millions of union members and at the same time expropriated the unions' assets. The Reich Labor Service (RAD), founded in June 1935, distributed workers to mainly civil projects and agriculture until 1941. This method of job creation was therefore viewed by the population and the foreign press as harmless compared to armament. It was compulsory for male adolescents between 19 and 24 years of age, and from September 1, 1939 also for female adolescents. By 1938, 350,000 young people were recorded in this organization, which was divided into 30 working districts . In the course of the war, more and more military projects were served by the RAD, such as the expansion of bunker systems.

With the fight against unemployment and with it the increase in the number of workers, workers' rights were dismantled. On May 2, 1933, the day after “ National Labor Day ”, the union buildings were occupied, assets were confiscated and leading officials were arrested. The law on the organization of national labor of January 20, 1934 led to the reinterpretation of employers as "managers" and employees as "followers". From 1936 onwards, there was a change from job creation to work allocation to forced labor . With the introduction of the work book that every worker had to keep, individual career opportunities were severely restricted by changing companies. The organization of the German Labor Front (DAF) under the direction of Robert Ley took over the formal mediation between workers and companies in the future. The DAF was strictly focused on the possibilities of increasing performance and the ideological alignment of the "following".

Strength-through-joy recovery work

One of the instruments frequently used by propaganda was the Kraft durch Freude (KdF) office, which was responsible for state-controlled recreation.

Expropriation of Jewish capital

A particularly unfortunate chapter in this context is the so-called Aryanization of Jewish shops and companies, as well as the public auctions of valuables and furnishings from Jewish property. While a total of around 100,000 businesses changed their owners in the course of the "Aryanization", participation in the auctions can hardly be quantified, but at least dimensioned using examples. In Hamburg, for example, in 1941 the loads of 2,699 freight wagons and 45 ships with “Jewish goods” were auctioned; 100,000 Hamburgers bought furniture, clothing, radios and lamps that came from around 30,000 Jewish families. In addition, there were thousands of changes in ownership of real estate, cars and art objects. Occasionally the authorities were harassed with requests for particularly coveted goods even before their rightful owners had been evacuated, and cases are described where Jews who have not yet been deported were rung so that one could see what was already on scheduled auction.

Nazi control instruments: cartels, foreign exchange offices and national control economy

From the very beginning, the Nazi economic leadership relied on a system of cartels and compulsory cartels , over which they had an ever increasing control and planning influence. Another strand of government control over the economy were the " foreign exchange offices " and "monitoring offices" (for foreign trade). The first complete records of economic sectors were made in agriculture and agricultural processing through the Reichsnährstandgesetz of 1933. From 1939 new types of economic organizations for industry emerged, for which the traditionally used term cartel was increasingly rejected: the Reich associations RV bast fibers, RV iron, RV coal , RV chemical fibers and RV Textilveredlung as well as the hollow glass association and the German cement association. The astonishing economic power and security of supply that the Nazi economy exhibited until almost the end can largely be traced back to innovative control, planning and rationalization techniques that were copied from the cartel system and then further perfected.

Key sector: the petroleum industry

On January 10, 1934, the Reich Ministry of Economics convened representatives of the German oil industry in Berlin. It was about finding and promoting what the German soil produced, for example on the edge of salt domes or in slate layers. The Reich drilling program proved to be quite worthwhile. The conveying capacity rose from 214,000 tons in 1932 to the peak volume of 1.06 million tons in 1940. Most of this was processed into lubricating oil.

In preparation for war, a strategic fuel supply was planned. With the participation of IG Farben, a front company called "Wirtschaftliche Forschungsgesellschaft mbH" (Wifo) was founded in August 1934 with the order to build large tank farms for the army and air force. Wifo was to keep around one million tons of fuel in stock at around ten locations in the Reich. The situation was critical when it came to aviation fuel, which could hardly be imported in the event of a war and Germany had no production facilities. IG Farben therefore concluded a license agreement with the US company Standard Oil - against the will of the US government - in order to be able to produce the necessary tetraethyl lead.

Foreign corporations dominated the German oil business. In addition to Standard Oil, the British AIOC (Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, predecessor of BP) and the Dutch-British Royal Dutch Shell were leaders. Your German group subsidiaries had more than two thirds of the refining capacity in the mid-1930s. They dominated 72 percent of the diesel fuel market, 55 percent of the gasoline market, and 50 percent of the lubricating oil market. Due to strict foreign exchange regulations in the German Reich, the German subsidiaries could hardly transfer their profits to the foreign parent companies.

In the 1930s, the main focus was on the synthetic production of fuels from coal in hydrogenation plants ( coal liquefaction ). So initially huge hydrogenation plants were built in Dortmund , Wanne-Eickel , Zeitz-Tröglitz , Leuna and Pölitz , and later also in other places, which never made independence from oil imports possible, but nevertheless allowed a huge increase in capacity.

Role of consumption

Private consumption, as domestic demand, was of no importance in the Nazi economy, since all resources were intended to serve to intensify armaments.

The wage freeze imposed by the regime remained in effect for the workers. However, due to the good economic situation and the shortage of skilled workers that soon became noticeable, numerous companies started paying higher piece wages or special allowances. Net wages in 1937, at least in the armaments-relevant economic sectors, reached the level of 1929 again, although prices also rose and, in addition to taxes and social security contributions, contributions to the DAF were automatically deducted from wages. The widening gap between collectively agreed wages and the disproportionately higher effective wages led to wage differentiation according to performance criteria, which replaced the previous order of social wage policy, which had been negotiated between trade unions and employers' organizations as social representative bodies in collective wage agreements.

In an international comparison of per capita national income, Germany in the 1930s was still half behind the USA, well behind Great Britain and still behind the Netherlands, France and Denmark. While in the USA the combination of series production through standardization and assembly line assembly on the one hand and high wages on the other hand created a rapidly growing domestic market even for expensive mass consumer goods such as automobiles, consumer goods production in Germany stagnated due to the exclusive concentration on armaments.

Although the regime tried to manufacture bulk goods through state-subsidized "Volks" products, only the Volksempfänger, which went into series production in the summer of 1933 and could be acquired with an installment contract, was a successful product. In 1933 a quarter of all German households owned a radio, in 1938 it was a little over 50 percent. Compared to 68 percent in England and 84 percent in the USA, that was not a great value either.

Last but not least, the project of a KdF car - Robert Ley 1938: "In 10 years every working German a Volkswagen!" - met with great approval. 336,000 people made weekly prepayments to get their own car. Since the politically set price of RM 1,000 was far below the production costs, no company was willing to build the Volkswagen. Instead, the DAF took over the financing from stolen union assets and commissioned Ferdinand Porsche with the development and construction of the KdF car. From the payments made by the future VW owners, DAF made a profit of around RM 275 million; the savers themselves lost their fortune, because, contrary to the promises of the regime for mass motorization, not a single one of the Volkswagen announced in propaganda was handed over during the Nazi era. Rather, Porsche delivered military vehicles for the Wehrmacht. Even those who owned a private car from another manufacturer were disadvantaged by the Nazi regime, because the price of gasoline in Germany at the end of the 1930s was twice as high as in the USA, for example, at 39 pfennigs per liter due to high taxation. In the Nazi regime, petrol was used as fuel for the military, not for private drivers.

Development in numbers

In 1938 the Hamburg World Economic Archive published an article by the British-Australian economist Colin Clark , which presented an international comparison of income. Accordingly, the standard of living in Germany was half that of the United States and two-thirds of that of Great Britain .

| Unemployment in relation to the development of industry | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 |

| Persons registered as unemployed, annual average (1,000,000) | 6.02 | 4.80 | 2.71 | 2.15 | 1.59 | 0.91 |

| Employees at the Reichsautobahn (RAB), annual average (1,000) | oA | <4.0 | 60.2 | 85.6 | 102.9 | oA |

| Development of German vehicle production, index (1932 = 100) | 100 | 204 | 338 | 478 | 585 | oA |

| Employees in the aircraft industry (1,000) | oA | 4.0 | 16.8 | 59.6 | 110.6 | 167.2 |

| Shipbuilding expenses (in millions of Reichsmarks) | 49.6 | 76.1 | 172.3 | 287.0 | 561.3 | 603.1 |

| Economic group | 1935 | 1937 |

|---|---|---|

| mechanical engineering | 70.6 | 95.4 |

| Electrical industry | 66.9 | 85 |

| Chemical industry | 76 | 87 |

| Textile industry | 59.5 | 66.9 |

Up until 1935, direct military expenditure was comparatively low at 18% of the entire household, increasing motorization was a measure of the population's prosperity and the German Reichsautobahn was a prestige object to demonstrate National Socialist efficiency.

By 1936, the promised recovery seemed over and the return to the world economy still possible. But with the upswing, Hitler and the NSDAP received confirmation that they had overcome the alleged "machinations of world Jewry" as the cause of the global economic crisis through national political measures. For the internally strengthened group of autarky and living space ideologues, it was time to take the next step: the intensification of direct armaments in preparation for a war of conquest .

However, all the economic measures taken by the National Socialists were not sufficient to fully utilize the production facilities, as the table opposite shows.

Central Germany was one of the big regional winners, where a new industrial center was built next to the Ruhr area. In cities like Magdeburg, Halle, Dessau, Halberstadt and Bitterfeld, the number of employees doubled within a few years. A city like Rostock with shipyards and the Heinkel aircraft factory increased its population within only six years, from 1933 to 1939, by a third from 90,000 to 120,000 and thus rose to the league of major German cities.

The arms-related expansion of the industrial sector was at the expense of agriculture. Young people were offered far better working conditions in industry, which was in dire need of workers. In November 1938, Reich Minister for Food and Agriculture Darré had to publicly admit that around 500,000 jobs had been lost in agriculture since 1933, a decrease of 20 percent.

From the state deficit to the war economy

Finance and monetary policy

As early as 1933, job creation and armament required the use of the printing press to realize them. The gold currency standard that many financial theorists were striving for at the time as a security against inflation had already collapsed in 1931. As President of the Reichsbank, Hjalmar Schacht enabled the circulation of “ special bills ” that were covered by the Reichsbank and guaranteed by the state. The connections to this change were initially hidden from the public. On the one hand, there should be no clarity about the extent of future armaments investments and thus about the breach of the Versailles Treaty. On the other hand, there should be no uncertainty about the position of the Reichsmark on the money market and thus undesirable devaluation (inflation) should occur.

For this purpose a dummy company was founded, the Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft mbH , behind which four well-known German companies stood, namely Siemens , Gutehoffnungshütte , Krupp and Rheinmetall . Mefo mbH had no other business purpose except as a financing instrument to legally enable the Reichsbank to discount your bills of exchange with a second signature . For armaments expenditure, 11.9 billion Reichsmarks were covered by these from 1934 until the Mefo bills of exchange imposed by Schacht in 1938. That corresponded to 30% of the Wehrmacht's expenses up to then and thus more than a thousand times the equity contribution of MeFo of only one million Reichsmarks.

In addition, interest-free imperial instructions (U-Schätze) and from May 1939 so-called NF tax vouchers ("New Finance Plan") were issued. In this way, 40% of the invoices issued to the German Reich were paid immediately and the rest credited as a tax discount.

The day after the Anschluss on March 12, 1938, the gold reserves of the Austrian National Bank were transferred to the German Reichsbank. The gold from Austria exceeded the German reserves by three times at that time. A total of 78.3 tons of fine gold worth 467.7 million schillings as well as foreign exchange and foreign currency worth 60.2 million schillings (= 4.4 million euros; 1.1 million Reichsmarks) (based on the lower Berlin exchange rates) transferred to the Reichsbank in Berlin. From then on, the term Nazigold / Raubgold (English looted gold ) is used to denote access to gold reserves of conquered countries and citizens by SS and government agencies until 1945.

The financial need for armaments was seen as a medium-term problem, a high level of debt, especially through short-term loans, was accepted. Territorial expansion forced by limited military action was to follow.

The inflation feared by many economists, which could be expected due to the abandonment of the gold standard and the increased debt, initially did not materialize. The state determination of the market organization and the control over pricing and profit margins by the Reich Commissioner for Price Formation put market economy principles out of force. The consumer price index only rose by an average of one percent per year. Since the stability of the Reichsmark thus enforced was purely political and not economically justified, the currency could not create confidence in the international money market. There was no major international investment in the German economy, which resulted in a chronic shortage of foreign exchange. The pent-up inflation led to the currency reform at the end of the war .

Götz Alys book about robbery and race wars (2005) and other authors try to prove that the wars of conquest of National Socialist Germany were always an attempt to conquer foreign currency or to control their use. The National Socialist government was forced to do this by its own unsound financial and monetary policy. Aly believes that the National Socialist government “initially worked with dubious and soon with criminal budgetary policy techniques”. From 1935 onwards, the German state budget could no longer be published, which primarily served to conceal the critical budget situation. "In their propaganda, the Nazi leaders boasted that they were laying the foundation for the millennial Reich, in everyday life they did not know how to settle their bills the next morning." The war costs were financed only to a small extent by regular state revenues, to a larger extent with the so-called silent war financing and by the occupied countries (see also: Hitler's People's State by Götz Aly). When that was no longer enough, the Deutsche Reichsbank was used as a lender. In fact, this meant that the German Reich was insolvent as early as the mid-1930s.

The economic historian Dieter Stiefel speaks of an “adventurous financial policy” with regard to the Mefo change ; the German Reich had "abandoned serious currency policy at the latest since 1934 and pursued state money creation".

According to an investigation in 1946, Nazi Germany looted gold worth $ 700 million in the occupied territories, most of it in Belgium and the Netherlands. Poland, on the other hand, had managed to get most of the central bank gold (worth approx. 87 million US dollars) to safety at the beginning of the war.

The control of the credit institutions by the regime was essential for financing in National Socialist Germany . The Minister of Economic Affairs Walther Funk became President of the Reichsbank in February 1938 . In addition to controlling the traditionally strong public banks in Germany, the NSDAP secured access to management functions at a number of private banks as part of the "Aryanization" process. The big banks tried to maintain parts of their independence, but from 1942/1943 had to come to terms with the Bormann Committee . At the end of the war, as a result of this policy, the assets of the banks consisted for the most part of (now worthless) loans from and claims on the Reich.

The rejection of free markets by the National Socialists with simultaneous use for their purposes was also evident in their policy with regard to the stock exchanges. The National Socialists were suspicious of the stock exchange business. For one thing, they rejected financial markets for ideological reasons. On the other hand, many of the trading participants were Jews. On the other hand, the stock exchanges were essential to finance the state and the economy. Like all other institutions in the Reich, the exchange boards were brought into line in 1933. Exchange boards of Jewish origin were removed from their functions, and the exchanges were organized according to the leader principle.

In order to eliminate competition between stock exchanges, an obligation was introduced in 1934 to trade securities exclusively on the home exchange. In the interests of further centralization, the number of exchanges has been significantly reduced. In 1934 the previously 21 German stock exchanges were combined into nine stock exchanges.

In order to strengthen the internal financing of the companies, the dividend distribution options were limited with the bond stock law of December 4, 1934. This severely reduced the attractiveness of the shares in listed companies. There were almost no new issues . Even if the economy grew by 50% from 1933 to 1938, the capital of the listed stock corporations stagnated. The number of listed companies also fell sharply. In 1933 there were around 10,000 listed stock corporations, in 1941 there were only 5,000 (in the Altreich, i.e. excluding Austria and the areas that were added). The issues of industrial bonds also fell from 1933 to 1938 from 3.4 to 2.9 billion Reichsmarks.

In return, the National Socialists used the stock exchanges to finance the massively increased national deficit . The volume of listed public bonds rose from 10.8 billion (1933) to 24.1 billion RM (1938). This “strong expansion of the use of credit for public employment measures” contrasted with a “reduction in the credit accepted by the private sector”. The historian Karsten Heinz Schönbach accuses the big banks of willingly crediting a considerable part of the armament.

Shortage economy: raw material situation with scarce resources

Agriculture and Food

As early as the spring of 1933, the Reichslandbund, an association closely related to the NSDAP, brought into line all agricultural political interest groups. On April 4, 1933, a newly created "Reichsführergemeinschaft" took over the representation of the entire German peasant class externally. One day later, the German Agriculture Council, as the umbrella body of the Chambers of Agriculture, promised the government its full support.

Richard Walther Darré , Reichsbauernführer of the NSDAP, was elected President of the German Agriculture Council. In 1933 Darré, meanwhile Reich Minister for Food and Agriculture, combined various branches of agriculture in the Reichsnährstand as a central association through compulsory membership. These included forestry, horticulture, fishing and hunting, agricultural cooperatives, agricultural trade and the treatment and processing of agricultural goods. The threads of the agricultural production and distribution systems came together there until 1945.

The market organization created by 1935 was a preliminary stage of the later war food regime. This differed from the market organization in peacetime "not in the way, but only in the degree".

Although consumer prices and wages rose in the agricultural sector by 1935, a further increase in the price of basic foodstuffs had to be prevented. The average industrial wage relevant for calculating the planned upgrade should remain a stable factor and not be driven up by price increases. By 1938, consumer prices fell back to the 1933 level. The Reichserbhofgesetz of 1933, which forbade the owners or their heirs to sell farms above a certain size, helped to prevent rural exodus. In no other sector in the Third Reich were party and economy so closely intertwined as in agriculture.

Despite the declaration of the "production battle" by Darré, the total agricultural area was reduced by approx. 800,000 hectares from 1933 to 1939. The reason for this was the use of the land by the Reichsautobahn and the Wehrmacht. The construction of the west wall alone required 120,000 hectares of agricultural area. In addition, there was a lack of fertilizers and incentives in the pricing policy. The stagnation of grain production began, which hardly came close to the production figures of 1913. After the beginning of the war, production even declined. The biggest deficit, however, was in the supply of fats and vegetable oils, up to 50% of which had to be imported through clearing agreements with Denmark and the Baltic states.

From 1933 to 1938, around 500,000 agricultural jobs were lost, a decrease of 20 percent.

In 1939 the German Reich, now with the Saarland, Austria, the Sudetenland, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Memelland, had 83% self-sufficiency in the food sector.

Stagnating foreign trade and shortage of foreign exchange

Even before 1929 there was a noticeable tendency for European foreign trade to be restricted to trading partners in Europe or in neighboring areas with a common national border at the expense of the overseas states.

The controlled foreign trade under the conditions of the "New Plan" also looked for European countries rich in raw materials that were interested in a direct exchange of goods with commercial goods of German industry. In 1934, trade agreements were concluded with Yugoslavia and Hungary in which imports and exports to a certain country were offset in terms of value and accounted for by means of clearing . This modern type of bartering saved the foreign exchange and gold reserves of the German Reich, which were needed for the purchase of armaments. To this end, the Reich concluded trade agreements (such as the German-British payment agreement of 1934 ) with almost all important trading partners. In the north, too, states such as Sweden , Denmark and the Baltic states concluded trade agreements with the foreign exchange weak Third Reich. Iron ore imports from Sweden, which are important for armaments, increased fivefold between 1932 and 1936. The continuously increasing demand for iron ore could not be met. This shortage even led to a decline in aircraft production in 1937, which also slowed the Navy's fleet expansion plan.

In spite of clearing agreements that were gentle on foreign currencies and an increase in domestic trade, the volume of foreign trade had not increased significantly until 1936. However, the share of armaments-relevant raw materials was significantly increased by state control, and the share of consumer goods was reduced accordingly. The focus was on the import of metals, fuels, rubber and cotton.

| Suppliers of iron ore by proportions in percent | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 |

| Sweden | 56.8 | 39.1 | 44.6 | 44.0 | 41.0 | 48.7 |

| France | 19.5 | 39.9 | 37.1 | 27.8 | 23.0 | 13.4 |

| Spain | 7.6 | 9.3 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 8.2 | 5.9 |

| Norway | 6.4 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

The desired self-sufficiency could almost only be achieved in the food and chemical sectors. When the war broke out, the foreign dependency for raw materials amounted to around 35 percent of the total requirement, in many armaments-important areas considerably more.

| Dependency abroad when war broke out in 1939 | Iron ore | copper | Mineral oils | rubber | Food fat |

| Foreign dependency as a percentage of total requirements | 75 | 70 | 65 | 85-90 | 50 |

| Of these, assessed as "blockade-proof" (percent) | 54 | 15th | 22nd | 4th | 75 |

Germany's accumulated short-term debts were frozen in the standstill agreement and reduced in the long term. This also made an important contribution to countering the shortage of foreign exchange.

Boycott movements abroad against German goods, such as B. the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League , created additional difficulties for German foreign trade.

After the foreign policy aggression of 1938, the USSR became the most important foreign trade partner of the “Greater German Reich” ( German-Soviet economic agreement ). The complete supply of raw materials to a warring Germany was, according to the assessment of the Reich government, "only possible with the raw materials of Russia [...]."

Racial politics, compulsory levies and corruption

The “redeeming” anti-Semitism typical of the Third Reich aimed equally at the personal annihilation and robbery of the Jewish population. While the regime played down the kidnapping and murder of people as "resettlement", robbery and extortion were described as " Aryanization " of previously illegally acquired and therefore illegal property of people of Jewish origin.

The willingness to enrich oneself personally from the victims of anti-Semitism ran through practically all social and political classes. Since the "Aryanization" was not monitored centrally by a ministry, but was delegated to the Gauleitungen, members of the lower political management levels were also given the opportunity to enrich themselves, robbery and blackmail.

As a rule, the perpetrators drew the assessment of their moral justification from their self-perception as victims during the " fighting time " of the NSDAP up to 1933. The propaganda statement that "thousands and thousands" of supporters of the NSDAP had made considerable personal and economic sacrifices, even through the financial exploitation by Judaism had been driven into suicide gave rise to moral claims. After party members had participated on a broad basis in the enrichment of stolen goods, especially real estate, after 1933, there was a further radicalization in the "Jewish question". The idea that the abducted rightful owners of the seized property could return and claim their property became increasingly intolerable. Together with previously cherished racial ideologies, a “final solution” to this situation became desirable for many.

Although the German Reich claimed the right to dispose of the “Aryanized” assets, it is questionable and still incomprehensible to this day what percentage of the stolen assets were actually passed on to government agencies. In the course of the November pogroms in 1938 , Hermann Göring initiated the Jewish property tax of one billion Reichsmarks, which supposedly corresponded to about six percent of tax revenue. After the night of the pogrom, the Jews were taken into preventive custody and plundered on their way to or from the concentration camps and forced to transfer assets. From Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler , who was officially responsible for the distribution of the looted property, to the Reich Treasurer of the NSDAP, altruism and legal conformity were demanded, but in practice they were broken with or without the knowledge of the party, depending on the need and occasion. A "special account S" was set up for Himmler, and donations from the Friends of the Reichsführer SS , also known as the "Keppler Circle", amounted to millions. The members of the Freundeskreis benefited from the "Aryanization" on a large scale. In addition, a special account was set up at the disposal of the SS in secret agreement with Economics Minister Funk, which was replenished from the proceeds of the valuables of the Jews robbed and murdered in the concentration and extermination camps.

Outwardly and in accordance with the National Socialist “concept of honor”, the persecution of the Jews according to Himmler was only allowed to pursue ideological, but not profit-seeking motives. Under certain circumstances, this would have spared possessed Jewish people. In the implementation, however, enrichments to Jewish property were only prosecuted in exceptional cases, for example if an unpopular party member could be removed at the same time.

The range of attacks ranged from extorting protection money from local SA or SS groups against private individuals to extorting several million Reichsmarks from industrialists using preprinted "donation forms" with threats of immediate execution. Looted art treasures found widespread use among party leaders, soldiers were often "given" real estate. As soon as Adolf Hitler took office, so-called “special funds” were created which were beyond any control by the audit office. In addition to “Aryanized” assets, it also collected private donations, party donations and proceeds from the forced sale of Hitler's book “Mein Kampf”. Up until the end of the Third Reich, a large number of such "special funds" were used and exhausted by various people or groups. Adolf Hitler evidently did not always rely on the ideological solidarity of his followers, but also tried to oblige them with substantial material donations, bypassing the tax authorities. The outrage was therefore great when it became known that some suspects of the conspiracy surrounding the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 had received such benefits.

The corruption established in the National Socialist system of maintaining power also burdened the state budget. From 1937 to 1941, the Reich Treasurer of the NSDAP handled over 10,000 reports of evasion of party assets by party members. The economic upswing of the German Empire was not promoted by the "Aryanization". From an economic point of view, it only led to a shift from rightful to illegitimate owners, but not to added value. As a result of the kidnapping, murder and emigration of large parts of the Jewish population, qualified skilled workers and managers were lost in the German economy.

Nazi planned economy: armament under the sign of the four-year plan

After almost four years of military economy under National Socialist rule, the economic reserves of raw materials and food were exhausted. Foreign trade stagnated, foreign exchange income from exports was not to be expected, as German industry was prevented from exporting by the self-sufficiency movement. The armament of the Wehrmacht could not be continued to the extent required by Hitler without additional raw materials.

In September 1935, Hitler outlined in his proclamation to the Nazi Party for the first time the principles of the Four Year Plan. The decision was made to "make Germany independent of imports by producing its own materials." As materials, he named "gasoline from coal [...], German fibers, artificial rubber, developing our own oil wells, our own old and new ore deposits".

A proposal from the industry, the IG-Farben , suggested that the deficit in raw materials could be pushed forward by bundling all forces to increase production in the country so that at least minor military actions would be possible. The patents owned by IG-Farben for the production of synthetic rubber ( Buna ) and for fuel production from lignite hydrogenation should contribute to this.

Encouraged by this, Hitler announced the introduction of a four-year plan at the Nuremberg Rally in September 1936 . The driving force behind the plan was Hermann Göring , from whom Hitler had asked in the summer of 1936 for reports on the economic situation and proposals for solutions to the most urgent problems. Göring collected memoranda from various economic sectors, but with his plans met the resistance of Reich Economics Minister Hjalmar Schacht . At the end of August 1936, probably at Göring's suggestion, Hitler dictated a memorandum consisting of an ideological section on the “political situation” and a programmatic section on the “economic situation” in Germany. The latter was based on the raw materials program influenced by IG Farben and resulted in partial self-sufficiency. The maximum increase in domestic production should allow food imports without affecting armament. The nation does not live for the economy, according to Hitler, "but finance and economy, business leaders and all theory have to serve exclusively this struggle for self-assertion of our people". Hitler threatened: “But the German economy will understand these new economic tasks or it will just prove to be incapable of continuing to exist in this modern age when a Soviet state is setting up a gigantic plan. But then Germany will not perish, but at most a few economists will. ”Hitler advocated a multi-year plan to make the Wehrmacht operational and the economy ready for war within four years.

Hitler summarized his economic policy memorandum of August 1936 in two central demands: "1. The German army must be operational in four years. 2. The German economy must be capable of war in four years." There was no question of war externally, instead it was pretended to strive for economic self-sufficiency in Germany.

Hitler had no clear ideas about the concrete organization of economic planning. Rather, he was guided by ideological maxims and questions of propaganda. But with Hitler's memorandum behind him, Goering enforced his claim to control the armaments industry. As a “representative for the four-year plan”, he quickly organized a group of “special representatives” for different aspects of the four-year plan, who often intervened in the Ministry of Economics' tasks with their own bureaucratic apparatus. The four-year plan triggered a tremendous economic impetus, the dynamics of which met Hitler's ideological claims. The policy of rearmament was raised to a new level in order to prepare Germany for the war that Hitler believed was inevitable.

The “exclusion of the question of profitability”, however, led to a serious conflict with the German metallurgical industry. The latter refused to invest in a company that was bound to fail economically. The smelting of 30 percent iron ore instead of 60 percent was not profitable, according to the industry, because it required high capacities. This view was supported by Minister of Economic Affairs Schacht, who saw the limits of armaments being reached with the limits of economic efficiency.

On the occasion of the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in February 1937, Hitler replied that the private sector was "[...] either able to solve the iron ore problem or it was forfeiting the right to continue to exist as a free economy" .

With this in mind, Hermann Göring founded the "AG for ore mining and ironworks Hermann Göring" on July 23, 1937 as the basis for the later Hermann Göring works . The required private ore fields were expropriated, the state took control of the entire steel production capacity in private hands. The Reichswerke Hermann Göring were next to the IG Farben and the United Stahlwerke AG the largest German group in the National Socialist German Reich .

In principle, the economy should be so drained that war, albeit limited locally, to replenish resources became inevitable. Schacht, whose economic ministry was reduced in importance by Göring's power of disposal, initially sought support for his criticism from the Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, Werner von Blomberg . However, he was loyal to Hitler. In November 1937, Schacht resigned as Reich Economics Minister , but retained his position as President of the Reichsbank until March 1939.

Walther Funk , who previously worked in propaganda, was appointed Reich Minister of Economics in February 1938 and in 1939 he also took over the presidency of the Reichsbank from Schacht. He fulfilled this task, as he explained at the Nuremberg war crimes trials in 1946, as "receiver" of Göring's orders. Funk was instrumental in pushing Jews out of business life. With the “Ordinance on the Registration of Property of Jews” of July 6, 1938 and the “Third Ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act” of June 14, 1938, the economic activity of Jews was recorded, controlled and finally brought to a standstill.

With the four-year plan authority, an instrument was to be created that secured the priority of military interests over private-sector influence. For this purpose, the Wehrmacht High Command (OKW) awarded the title of Wehrwirtschaftsführer to civil industrialists. This should deepen the bond with the military structure. The head of the Defense Economy and Armaments Office , General Georg Thomas , was responsible for this initiative. But the composition of the four-year plan authority led to an expansion of the influence of the industrialists involved. The Wehrmacht as a whole was prevented from unified development by Wehrmacht leadership crises. The individual Wehrmacht parts of the army, air force and navy were in competition with each other and were upgraded at the discretion of their commanders in chief. There was no uniform "image of war" given by politicians. Technologies such as radio measurement technology ( radar ), jet engines or the development of nuclear weapons (“ uranium project ”) were misunderstood in terms of their importance for a possible “great” war. Instead, prestige objects such as an aircraft carrier that was never completed or production lines of already obsolete aircraft that were only geared towards number of items were approved.

The "Anschluss" of Austria and the "Sudeten Question"

Two years after the proclamation of the four-year plan and the formation of an extensive bureaucracy to implement it, the interim objective was not met. Due to military participation in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, expectations arose in terms of an intensive exploitation of raw materials. Spain , which remained the third most important supplier of iron ore after Sweden and France and which also covered 50% of the pyritic sulfur requirement, successfully resisted further cupping by the Third Reich under Francisco Franco .

Although strong increases were recorded in the field of fuel and buna production, which were due to the armaments policy engagement of IG-Farben, the increase in steel production fell far short of armaments expectations. Although the four-year planning authority tried to control all areas of the economy, the deficits in the area of consumer goods were evened out by companies that were not recorded.

In view of the deficit development, it is remarkable that Hermann Göring was instrumental in the “Anschluss”, the occupation and incorporation of Austria on March 12, 1938, from his desk via telephone calls with the Austrian decision-makers. Austria was the first country to be “[…] conquered by telephone”, and Göring was the conversation “partner” on the side of the German Reich.

With the incorporation of Austrian steel production, surplus agricultural production - particularly urgently needed fats - oil production in newly discovered oil fields, unused hydropower for energy generation and the state treasure trove of gold and foreign exchange, the half-time target of the four-year plan was reached.

Just a month later, the " Sudeten question " became the focus of foreign policy interest. Encouraged by the signs of an approaching war, the IG Farben presented the new generation plan for the defense economy . This envisaged growth rates between 60 (aluminum) and 2300 percent (Buna) in the chemical sector by the planning year 1942/43. The Defense Economic New Generation Plan , also known as the Krauch or Carinhall Plan, revised the four-year plan upwards and led to the rise of IG Farben director Carl Krauch to become the most powerful man in the four-year plan organization behind Göring. In August 1938, this plan was expanded to become the express plan , which shortened the term by one year. With this, the risk of a ruin of the national economy was accepted, in the hope of a war booty that could be achieved through wars of conquest.

However, under the aspect of the appeasement policy, the Sudeten crisis was diplomatically settled by the Munich Agreement and allowed the German Reich to annex the Sudeten areas. Although the resources thus acquired were immediately incorporated into the four-year plan and the new military generation plan, they did not compensate for the costs of the foreign exchange and raw material-intensive preparations for war. Rather, the integration of the so-called “rest of Czech Republic”, ie the territory of Czechoslovakia apart from the Sudeten area and Slovakia, offered a military economic perspective. Since Czechoslovakia initiated the military mobilization itself in the face of the threat , the German Reich could expect not only foreign currency, raw materials and industrial facilities but also a significant amount of finished armaments as booty. On March 15, 1939, German troops finally marched into Prague and established the “ Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ”, which was supposed to be conceptually independent, but was de facto entirely geared to the needs of the German Reich. During the invasion, captured armaments were transported to Germany on a large scale. Slovakia , which had been declared independent the day before, was also under direct control of Germany.

War economy

Even if, despite aggressive territorial expansion policy, no declaration of war was made on the “Greater German Reich” by September 1939, preparations for it had been made in Germany. On August 29, 1939, three days before the start of the war (or four days after the original order to attack Poland ), rationing began with the distribution of ration cards . A famine like the one in World War I should not turn the population's lack of enthusiasm for a new great war into open protest. The economy itself hardly changed in the first half of the war compared to the military economy of the prewar years. The rapid overthrow of Poland in association with the Soviet Union was a continuation of the gradual territorial expansion that had begun in March 1938 with the annexation of Austria . Despite food rationing, the economy was still engaged in the production of consumer goods, so that the civilian population mostly perceived the consequences of the war as mild until the start of the Allied bombings. In addition, soldiers brought food and other goods via extensive transports in the holiday trains or field post parcels sent en masse from the conquered and occupied territories to the German Reich. Work on major non-military projects such as the world capital Germania continued until 1943. The organization of the economy had become confusing due to numerous offices of the Reich government, the NSDAP and the Wehrmacht, "acting according to direct orders", for example through Führer decrees, replaced coordinated planning. The four-year planning authority continued to exist after the end of four years in 1940 until the end of the war, but lost its importance as the war progressed.

At the beginning of the war there were a number of different authorities in Germany that competed against each other in the field of armaments and armaments industry. Hitler's policy to set up special staffs for special tasks, which were then headed by a high-ranking personality, meant that there was no central authority that could intervene to regulate the situation.

Hermann Göring as head of the four-year plan authority , General Georg Thomas as head of the Defense Economics and Armaments Office and Fritz Todt as Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition took care of the armaments . In addition there were the general staffs of the troops and of course Göring's very special influence on the air force . Thomas said about this parallelism:

"Today I am expressing quite openly what I have represented for years: our military external organization with the numerous positions that are involved in military economics today was a freak in peacetime, it is impossible for war."

Forced labor

In addition to the inmates of the pre-war concentration camps (mostly political prisoners, so-called anti - socials and Jews), 300,000 of the total of 420,000 Polish prisoners of war were still "deployed" in 1939. Either in occupied Poland or in the “Old Reich” they were used for forced labor under harsh conditions , initially mainly in agriculture. The Polish civilian population was initially left with recruitment on a voluntary basis. On April 24, 1940, the governor general of the occupied Polish territory, Hans Frank , issued a “call” to initiate compulsory “recruitment” measures if necessary. A total of over 2.8 million Polish forced laborers were employed in the German Reich. After the Barbarossa company , general on-site work was introduced in Russia on December 19, 1941. Several million workers, mostly forced laborers, from the territory of the Soviet Union (so-called eastern workers ) and Poland were deported to Germany in order to alleviate the labor shortage caused by the war. In France, the compulsory service in Germany Service du travail obligatoire (STO) was introduced in 1943 , the Italian military internees and contingents from the occupied countries were added. In order to be able to meet the huge demand for labor for the construction of the Atlantic Wall , the order was issued on September 8, 1942, to bring in the population of the occupied territories in violation of international law.

The “value” and thus the area of deployment of the forced laborers was determined by racial criteria, prisoners of war of the Red Army and Jewish concentration camp inmates ranked at the bottom. The fact that forced laborers perished as a result of inadequate nutrition, inadequate clothing and lack of medical care represented part of the implementation of the National Socialist racial policy and was accepted with approval. The cynical slogan “ Arbeit macht frei ” was placed as an inscription in the entrance area of many concentration camps. Towards the end of the war, over nine million forced laborers, 7.6 million of them civilians, were employed in the German Reich, which corresponds to a quarter of the total population in the labor process.

Attrition and resource overload in war

Situation after the lightning campaigns

Although the attack on Poland lasted only 36 days, it was not without consequences for the operational readiness of the Wehrmacht. The army had lost about 30% of its vehicles (details here ); the air force suffered fewer losses, the navy was still in the midst of the development phase and, after Great Britain declared war, faced the clearly superior rival Royal Navy . A " seated war " on the border with France, characterized by little activity, gave the Wehrmacht six months that could be used for further training of the troops. The general mood of victory was dampened by the uncertainty about the further course of the war against France and England: Both countries were now arming against Germany. The lack of raw materials was exacerbated by the lack of French iron ore imports, because the stocks captured in Poland could not make up for this loss. A threat to Swedish ore imports from activities of the Royal Navy in the North Sea would have put an immediate end to German armaments. So a company to secure the North Sea coasts with the profit of Norwegian mineral resources was obvious: the Weser Exercise company , the conquest of Denmark and Norway. But this largest use of surface warships of the Kriegsmarine in the Second World War was accompanied by serious losses of warships that were extremely resource-intensive and labor-intensive in the production (see also the German ships involved in the Weser Exercise Company ).

Construction of the Graf Zeppelin aircraft carrier was discontinued because the shipyard capacities were needed to maintain the rest of the fleet. All economic forces had still not been concentrated on armaments.

The general representative for construction, Fritz Todt , was appointed Reich Minister for Armaments and Munitions on March 17, 1940 and practically controlled the German war economy. He tried to apply the experiences from the Todt Organization , which he founded, and the construction of the Reichsautobahn to the organization of the entire armament. Under his chairmanship, he convened five main committees - each responsible for ammunition, weapons and equipment, armored vehicles and tractors, general Wehrmacht equipment and machines. The committee system should rationalize the provision of raw materials for certain armaments required at short notice and the division of tasks in their production . From 1940 onwards, these measures led, among other things, to the occasional shutdown of non-military operations; from 1943 onwards, such companies were closed on a large scale. The campaign in the west , which began on May 10, 1940 - before the Weser exercise was over - dictated the law of action, the civilian population was inspired by daily reports of success from the Wehrmacht against France, which was feared as an enemy of the war. Postcards from German soldiers who posed in front of tourist motifs from conquered France conveyed an image of lightness to “home”; likewise the German newsreel .

The large industrialists from IG Farben , Krupp and Thyssen, who were appointed " military economic leaders ", successfully defended themselves against a centralization of industry which would have forced them to give up their entrepreneurial pursuit of profit. The population's hope for an imminent improvement in the situation was nourished by Nazi propaganda and the absence of supply bottlenecks. Savings programs for the purchase of a private Volkswagen were operated by the German Labor Front and its KdF office until the end of the war , but the amounts paid were diverted to armaments. Only a few savers have ever been able to exchange their savings booklet, which is full of tokens, for a VW Beetle .

The capitulation of France in June 1940 led to a brief relaxation of the raw materials crisis. 1.9 million prisoners of war and several hundred thousand abducted Jews from the occupied territories were largely used for forced labor in France, the Benelux countries and the Greater German Reich. The French aircraft and vehicle industries were also committed to German armaments (e.g. Renault ). But after the losses of the navy, the air force and the land army were also drastically affected by wear and tear. The large area of the occupied territories led to a decline in personnel who were obliged to maintain order according to the Hague Land Warfare Code . The high manpower requirements of the Wehrmacht led to a withdrawal of 1.5 million workers from trade and industry, more and more women were recalled to industrial work after they had been removed from work by marriage loans in the pre-war period (see also Women under National Socialism ).

In the Battle of Britain the Luftwaffe experienced the consequences of gross planning deficiencies in the pre-war armament. While the more general tasks such as ground support and the achievement of air sovereignty against inferior armed forces were well carried out up to then, a fight against the Royal Air Force, which had been focused on home defense since 1935, was over English soil (Battle of Britain, The Blitz , aerial warfare in World War II ). has not been taken into account by the armaments industry. Like the navy during the Weser exercise, the “model air force” experienced Hermann Göring's conceptually conditioned military defeats. In the field of fighter aircraft production, German armaments reached 200 aircraft per month, only half of the English armaments that had already been completely converted to a war economy. Before his suicide, Ernst Udet, who is responsible for the technical development of the Air Force, protested that politics never prepared him for a war against England. In January 1939, Hitler himself explained to a group of submarine captains that England was no longer an opponent of the war. It remained for armaments to adapt to the needs of the campaign currently underway through improvisation at short notice.

Motives for the attack on the Soviet Union

Without the raw material imports from the USSR, a continuation of the war was no longer possible. The decision of Hitler to attack the USSR , fell in the summer of 1940 and should be implemented in May 1941st Due to the unforeseen Balkan campaign, the date of the attack was delayed to June 22, 1941. The aim of the war economy was, as Göring's economic policy guidelines of June 1941, the so-called Green Portfolio , said, "to gain as much food and mineral oil as possible for Germany" . The entire armed forces should be fed with food from the occupied territories and an additional 8.7 million tons of grain per year should be brought from the occupied territories to the German Reich. The planners around Herbert Backe and General Thomas calculated the starvation of millions of people.

The " Blitzkrieg " should enable the conquest of Russia in four months. But the hitherto successfully concentrated attacks on the weakest point of the enemy were more a product of favorable opportunity than of long-term military planning within economic possibilities. In the winter of 1941, after the navy and the air force, the land army came into the position of being completely exposed and not prepared for a winter war. Together with the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, the Russian winter war forced a turn in the German economy from a military economy to a war economy . However, it would take a whole year before the centralization of industry by the successor of the unfortunate Todt, Albert Speer , was complete. Despite a plentiful supply of raw materials compared to the pre-war years, the supply situation was endangered because there was a lack of means of transport for the widely distributed sources of raw materials. Soviet prisoners of war regarded as "racially inferior" were largely excluded from the food supply. Hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war, concentration camp inmates and forced laborers starved to death.

Critical situation in the supply of oil and fuel

Supplying the Wehrmacht with oil and fuel was Germany's Achilles' heel throughout the war. The Reich Ministry of Economics summarized the calculations on October 1, 1939. After that, the fuel was only sufficient for Wehrmacht aircraft and vehicles for four and a half months. In 1941, the Wehrwirtschaftsamt calculated in a memorandum for General Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel , the head of the Wehrmacht High Command, that 400,000 tons of fuel were missing every month.

Hitler increasingly recognized this critical situation in the course of the war. In June 1942 he flew to Finland to pay homage to Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim on his 75th birthday, as the Finns were also fighting against the Soviet Union, and there he said: "We have a large German production; but what the Luftwaffe alone devours what devouring our armored divisions is something really monstrous. It is a consumption that goes beyond all imagination. " His country depends on imports, said the Nazi leader: "Without at least four to five million tons of Romanian petroleum we would not be able to wage the war and should have let it go." Hitler's massive armed forces would have collapsed in a short time without a steady influx of fuel and lubricating oil. Sources say that the Wehrmacht never had more than 14 days in reserve during the entire war. According to the historian Rainer Karlsch, around a quarter of the 11.3 million tons of mineral oil that were available to the German Reich in 1943 came from imports, most of them from Romania. A good half came from the liquefaction of coal in hydrogenation and synthesis plants, while 17 percent came from German and Austrian sources.

This constantly tense situation explained the central importance of the Austrian and Romanian oil fields as well as those in Galicia in the conquered Ukraine. As early as May 1940 the government in Bucharest signed the so-called " Oil-Arms Pact " with Berlin, which regulated the exchange of German arms for Romanian oil from the region around Ploiesti .

The advance of Army Group South towards the Caucasian oil fields in the summer of 1942 can serve as evidence of the extremely critical situation. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel said in this regard: "It is clear that the operations of 1942 must bring us to the oil. If this does not succeed, we will not be able to carry out any operations in the next year."

Even during the Russian campaign, the Wehrmacht was able to conquer Russian fuel depots. These depots were mostly diesel stocks, while the Wehrmacht primarily used gasoline. Even towards the end of the war, during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, the Wehrmacht tried, largely unsuccessfully, to conquer Allied fuel depots because the lack of fuel prevented any forward movement. In the last months of the war, the Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht still had planes or tanks, but hardly any significant fuel reserves to operate. The catastrophic fuel supply from mid-1944 onwards had three main causes: First, the Red Army was able to conquer the oil fields of Ploiesti in August 1944 . Second, an emergency program, the so-called mineral oil security plan, failed . Thirdly, it was only at this point that targeted bombing attacks by the Western Allies began on the German oil industry.

Centralization and rationalization of the war economy

Compared to the USA, rationalization measures were only moderately implemented in Germany in the 1930s. The armaments contracts during the four-year plan were carried out on the basis of cost recovery with fixed profit margins of three to six percent between government and industry. There was no incentive for companies to rationalize ; the production costs would have fallen, and with them the order volume and profit. Due to the payment method, it was in the business interests of the industry to produce in a costly manner. Surpluses of the allocated raw materials were partially hoarded and used for the profitable production of consumer goods.

The increasing control of the armed forces over the economy did not advance the rationalization either. High military officials preferred a wide range of different complex weapon systems, which ideally were elaborately handcrafted. Assembly-line production and mass-produced goods were viewed as inferior and underestimated for weapon manufacture. For the fight they wanted the highest possible quality and complexity regardless of the cost issue, which had to be clarified by politics.

It was not until 1941 that various bodies complained about the insufficient production output in relation to the funds invested. The committee system set up by Fritz Todt was supposed to coordinate the manufacture of armaments, combine uneconomical double orders and optimize the distribution of raw materials.

As early as the summer of 1940 he founded the first ammunition committee and tried a completely new form of armaments organization. This first “prototype”, modeled on which the entire industry was later reorganized, worked as follows: A main committee was formed and a number of special committees . In the main committee , all planning for production was regulated and the necessary agreements made. The special committees were each assigned to a type of ammunition and provided the necessary preparatory work.

Every material request by the Wehrmacht was now submitted to the main committee after Hitler found it good . He then distributed the orders and the necessary raw materials to the respective companies, but did not talk them into the production process. The main result of this new structure was that large parts of the military's control were removed. For this purpose, the industry could now be used on a project basis, i.e. much more efficiently and utilized. The committee system was extended to the tank industry as early as November 1940, and later also to the arms industry, as it proved to be a very effective innovation.

Todt then expanded the system from pure production to development. One of the main tasks of the development committees was to curb waste. Up to now, for example, it was common for the navy and the army to have heavy artillery (one mobile, one bolted onto ships), but that their specifications differed so much from one another that neither spare parts nor ammunition were compatible. By standardizing these , further rationalization reserves ( economies of scale , experience curve ) opened up.

Speer took over the committee system from Fritz Todt and made further adjustments to the industry. He assigned so-called "sparing engineers" to the companies in order to optimize the consumption of raw materials. As a result, the production number of aircraft quadrupled between 1941 and 1944, the amount of aluminum consumed only rose by five percent.

A nightly inspection of 20 large companies in Berlin in the spring of 1942 found that all of the companies examined only worked one single shift. At the same time, however, 1.8 million workers were employed to expand production facilities, with an order value of 11 billion Reichsmarks. Speer ordered the shutdown of new constructions with an order value of 3 billion Reichsmarks, and renounced further shutdowns only in response to Hitler's protest. The companies were required to work in shifts ; in this way the existing production facilities were better utilized.

As early as October 1941, Göring had signed a decree that stipulated fixed-price contracts for order processing with the armaments industry instead of the previous cost coverage contracts. It was not until January 1942 that Todt succeeded in enforcing this practice against the resistance of the Wehrmacht. Settlement through fixed-price contracts was an important tool for Speer to drive industry to increased productivity. Because the more cost-effective and efficient production was, the more profit could be made. Simplification of production methods, simplified constructions suitable for mass production, restriction of the product range, company mergers and careful raw material exploitation were the result in all areas. Companies that could not adapt to this development were closed and the capacities that became available were distributed to more productive companies. For example, the Luftwaffe's fire-fighting equipment was manufactured by 334 different companies in 1942. By early 1944, the number of manufacturers had been reduced to 64 and 360,000 man-hours saved per month.

This strategy was also applied to consumer goods production. It was surveyed that five of 117 textile manufacturers did 90 percent of the production, the remaining 112 companies only 10 percent. The 112 less productive factories were closed and their workers assigned to the arms industry.