Spanish Civil War

| date | July 17, 1936 to April 1, 1939 |

|---|---|

| location | Spain , Spanish colonial empire |

| exit | Victory of the coup plotters |

| consequences | End of the Second Spanish Republic , Franco dictatorship |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

Supported by

|

Supported by

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Gijón - Oviedo - Alcázar of Toledo - Mérida - Badajoz - Guipúzcoa - Mallorca - Sierra Guadalupe - Talavera de la Reina - Madrid - Road to Coruña - Málaga - Jarama - Guadalajara - War in the north ( Durango , Guernica , Santander ) - Brunete - Belchite - Teruel - Cabo de Palos - Aragon - Ebro - Catalonia

The Spanish Civil War (also known as the Spanish War ) was fought in Spain between July 1936 and April 1939 between the democratically elected government of the Second Spanish Republic ("Republicans") and the right-wing putschists under General Francisco Franco ("Nationalists"). With the support and after military intervention of the fascist or National Socialist allies from Italy and Germany, the alliance of conservative military, Catholic CEDA , the Carlist and the fascist Falange triumphed . This victory was followed by the end of the Republic in Spain and the Francoist dictatorship (1939–1976), which lasted until Franco's death in 1975 .

background

causes

The reasons for the outbreak of the war can be found in the extreme socio-political and cultural upheavals in Spanish society as well as in regional strivings for autonomy, for example in the Basque Country and Catalonia . Spain has suffered numerous violent conflicts that have remained unsolved since the mid-19th century. They increased and increased when, after the defeat in the Spanish-American War in 1898, the reputation of the old institutions had largely been lost. The few supporters of the Second Spanish Republic had neither succeeded in remedying the serious social grievances nor countering the advocates of an authoritarian state order.

Spain faced several structural problems before the civil war:

- the completely underprivileged position of the agricultural and industrial workers, some of whom sought radical social upheavals

- the contradiction between partly feudal structures in rural areas and the advanced industrialization in urban centers like Barcelona or Madrid

- the dispute over the cultural monopoly between the Roman Catholic Church and the secular liberal-republican forces

- the efforts of the Basques and Catalans to emancipate themselves from central government, which met with fierce opposition

- the lack of control of the military by the government, its alienation from large parts of society and its role as a “state within a state”.

In recent Spanish history, peaceful solutions have hardly had a tradition. For a long time , clerical- monarchist , republican, bourgeois- liberal , socialist , communist and fascist groups faced each other irreconcilably. Because of the economic crisis in Spain and the changing situation in Europe due to the emergence of fascism , the situation became noticeably worse.

prehistory

After initial enthusiasm, the Second Republic, founded in 1931, quickly lost support. The traditional elites from the times of dictatorship and monarchy feared that their privileges and their cultural self- image would be endangered. The secular orientation of the first government and the attacks on church institutions inspired by radical anti-clericalism strengthened this attitude. They opposed all reforms that held out the prospect of improving general living conditions.

The initial euphoria of the workers towards the republic also quickly cooled. After the social reforms had proven to be ineffective and the new right-wing government had taken a tough course in 1934, the organized workers saw nothing more than a continuation of the old policy of oppression in the new parliamentary form of government.

The anarcho-syndicalist CNT had fought the republic almost from the beginning and on January 8, 1933 and December 8, 1933, made two attempts at insurrection, albeit one that collapsed immediately; The previously reformist socialist trade union UGT turned to a revolutionary course from 1933 out of disappointment over the government alliance with the republicans and propagated the dictatorship of the proletariat . In parts of the research, however, it is doubted whether these were more than “empty revolutionary slogans” with which the leading socialists reacted to pressure from below. Significant sections of the socialist party PSOE clearly continued to rely on cooperation with the liberals.

The Republicans, who were preparing to reshape Spain, implemented many important reforms only half-heartedly. Large parts of the bourgeoisie nevertheless feared a dominance of the working class and were therefore ready to support a dictatorship. Added to this were the efforts of the Catalan and Basque bourgeoisie to leave the Central State , which was dominated by Castilian .

On August 10, 1932, a first military coup took place under General José Sanjurjo, centered in Seville , which was poorly carried out and thwarted by a general strike . The pardon of Sanjurjo, who was initially sentenced to death, and the small prison sentences for a few other officers involved, saw the rights as an incentive to prepare for the next attempt better and, above all, in the long term. As early as the end of September 1932, right-wing monarchists of the Acción Española formed a committee together with some general staff officers, which operated from Biarritz in France and was supposed to prepare a new coup through the conspiratorial networking of anti-republican officers (who had been organized in the conspiratorial Unión Militar Española since the end of 1933 ). In addition, the committee promoted the systematic journalistic delegitimization of the republic depicted as the product of a " Jewish - Masonic - Bolshevik " conspiracy. It also smuggled paid provocateurs into anarchist organizations in order to organize the “collapse of law and order”, an important pretext, in the immediate run-up to the planned coup.

Regardless of these efforts, there was a radicalization of right-wing discourse between 1931 and 1936, as pointed out by the British historian Paul Preston in 2012. In a multitude of newspapers, magazines and books - including the widely read Orígenes de la revolución española (1932) by the Catalan priest Juan Tusquets Terrats - it has been argued that leftists are "neither really Spanish nor human at all" and that the "erasure of the left as patriotic duty ”. Carlist and fascist authors in particular identified the entire Spanish labor movement with the medieval Muslim conquerors and called for a “second reconquista ”, which gave the attacks on the left an additional “racist dimension”. Also José María Gil-Robles , the leader of the "moderate" conservative Catholic CEDA , this rhetoric, which examined the entire left as "un-" or discredit "anti-Spanish" served. This potentially eliminatory aggressiveness merged, especially in the rural areas of the south, with the hatred of the big landowners for the farm workers, whose traditional fatalistic submission to the aristocracy had largely disappeared in the first years of the republic and given way to open demands for land and better pay. The militant rejection of the anti-clerical and social reform legislation of the republic, shared by the entire old establishment, was concentrated in the Spanish officer corps (and especially among the africanistas , the officers of the colonial army) - not least because the left-wing parties planned to traditionally notoriously oversize the scope of the republic Corps of officers to match the actual size of the army. The “instinctive hostility [of the officers] against the republic” was masked ideologically in the run-up to the civil war with the idea of a “Jewish-Masonic-Bolshevik conspiracy”. Franco was an avid reader of Tusquets' writings and a subscriber to the magazine of the Acción Española , and General Emilio Mola , the actual military planner of the coup of summer 1936, participated in this debate with his own publications since 1931. Mola ensured that the eliminatory dimension of this discourse also determined the concrete preparations of the conspirators: “The repression staged by the military rebels was a carefully planned operation with the aim of making those - in the words of the coup planner General Emilio Mola - 'without Scruples or hesitations [to eliminate] who do not think like us'. "

In autumn 1933 the first coalition broke up under Prime Minister Manuel Azaña , who succeeded a center government under Alejandro Lerroux , which was tolerated and elected by the right-wing parties . It pardoned the 1932 coup plotters and those convicted of crimes during the Miguel Primo de Rivera dictatorship , reversed the “meager” social and secular reforms and worsened the situation of wage earners. The left and liberal Republicans understood this as a declaration of war. When the CEDA entered government with three ministers at the beginning of October 1934, the UGT proclaimed a general strike, which the government put down with mass arrests as quickly as the attempt to proclaim an independent Catalonia in Barcelona. In Asturias , however, the strike took on the form of open insurrection, at the initiative of the workers and against the resistance of the union officials. The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 (also known as the “October Uprising”) gave a first foretaste of civil war with hundreds of deaths - the government proclaimed martial law . Under the command of the future dictator Francisco Franco, the uprising was brutally suppressed. There were at least 1,300 dead, 78% of them civilians. This was followed by a broad wave of arrests, which also affected top liberal and socialist politicians, and censorship that affected the left-wing newspapers. The CEDA led by José María Gil-Robles , a Catholic rallying movement that partly sympathized with European fascism, pushed to power, but failed because of President Zamora . Gil-Robles, temporarily serving as Minister of War under Lerroux, laid the foundation for the rise of the radicalized military group around General Franco, who prepared the conspiracy for rebellion by promoting them to high posts. Falange Española , founded in 1933 by the son of the ex-dictator Primo de Rivera, José Antonio Primo de Rivera , developed from a political splinter group into an equally serious militant factor.

At the end of 1935, the second coalition of Lerroux's radicals and the CEDA came to an end because of internal quarrels and a financial scandal. In order to take advantage of majority voting rights this time, socialists, republicans, liberal Catalanists, the Stalinist Partido Comunista de España (PCE) and the communist Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) formed a popular front alliance, the Frente Popular . They were supported by the Basque nationalists and the anarchists, who this time did not formulate an election boycott . In contrast, there was the Frente Nacional made up of CEDA, monarchists, a landowner party and the Carlist . In between stood the parties in the middle, which were hardly any more important.

On February 16, 1936, the Popular Front won the elections; the parliamentary opposition also recognized their victory. According to the most cited statements by Javier Tussell, the parties of the Left Popular Front received 4,654,116 votes in the first ballot, those of the Right National Front 4,503,505 votes and other parties (including the Center, Basque Nationalists and the Partido Republicano Radical) 562,651 votes. After the second ballot on March 1 and the action of a mandate review commission set up by the new government, this led to the following distribution of seats: Popular Front 301 seats (of which PSOE 99 and Izquierda Republicana 83), National Front 124 (of which CEDA 83), other 71 Information from various historians about the result of the vote count, which was not published in detail at the time, but not the distribution of seats, now partly deviate from one another. Some conservative historians also emphasize that irregularities in the counting of votes influenced the election results and the distribution of parliamentary seats in favor of the Popular Front. However, it was the right-wing CEDA that was stripped of several mandates by the review commission because of blatant election fraud in the provinces of Salamanca and Granada .

With the victory of the Popular Front, the republic ceased to exist for parts of the right. Despite the resumption of the reform program of the new government under Azaña, which was formed without a single socialist member, there were spontaneous land occupations, strike activity rose sharply and street fights between extremists from both political camps, some of which were violently suppressed by armed forces of law, increased significantly. The fascist Falange carried out targeted terror, against which the state showed itself powerless. The specter of a communist seizure of power in Spain was conjured up by the right, who no longer wanted to accept many of the government's decisions that favored the radical left.

Meanwhile, the officers planned the coup almost publicly. Their activities have been largely ignored or only slightly punished by the Azaña government. In a fight against the putschists, she would have had to arm the unions, which she wanted to prevent as much as possible. The new government had banished many officers suspected of anti-republicanism to remote bases on the Spanish islands and in Spanish Morocco, unwittingly encouraging their conspiracy and creating an impregnable power base for them. The colonial troops stationed in Spanish Morocco were among the most effective and feared opponents of the Republicans in the later civil war. In Spain itself, the activities of the conspirators were observed by officers of the anti-fascist secret society UMRA, the Unión Militar Republicana Antifascista .

At the height of the unrest, on July 13, the monarchist opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo was murdered by members of the Guardia de Asalto and the Guardia Civil in an act of revenge for the death of a UMRA member . His death moved the Carlist to support the coup with their paramilitary groups.

When the uprising began, it was mainly the workers who resisted. Wherever they were successful, they responded with a revolution that was mainly driven by the anarchists. This temporarily saved the republic's existence. The coup turned into a civil war that soon became part of Europe's international network, which was to have a decisive influence on the course of events.

Military coup

Initiated by a military revolt in Spanish Morocco , the military coup against the Second Spanish Republic began on July 17, 1936 . The coup plotters, who found sympathy with parts of the Spanish military on the Iberian Peninsula from the start , relied primarily on the Spanish colonial troops in Spanish Morocco (the Regulares , an army of Moroccan mercenaries, as well as the Spanish Legion ) and hoped to get the Gain control of the capital Madrid and all major cities.

According to General Emilio Mola's plans , the uprising in Spanish North Africa was originally scheduled to begin at 5 a.m. on July 18, and the mainland 24 hours later. The plans were discovered around noon on July 17th in Melilla , necessitating an early strike. The city of Melilla was brought under the control of the insurgents on July 17th. On July 18, shortly after 6 a.m., Franco sent a radio message to the army, giving the signal for an uprising. Up until this point, almost all military bases in Morocco were under the control of the coup plotters , except for the air force base at Tétuan , which soon fell. The Canaries , where Franco was in command, were also secured for the rebels that day. But the left on the island of La Palma was able to receive the republic there for a week during the Semana Roja .

The nominal leader of the military coup was General Sanjurjo, who had failed with a coup in 1932 and was therefore in exile in Portugal at the time. On the return flight from exile, the general had a fatal accident on July 20, which led to a power vacuum among the Spanish nationals. This was filled by a triumvirate of Generals Mola, Franco and Queipo de Llano .

The Madrid government learned of the uprising in North Africa on the evening of July 17, but reacted reassuringly as no unit on the mainland had yet joined it. Offers of help from the CNT and UGT and their requests to hand over weapons to them were resolutely rejected by Santiago Casares Quiroga on July 18 and the population asked to go about their normal work. Casares Quiroga still believed that General Queipo de Llano would not take part in the uprising and restore order in Andalusia . In fact, Queipo had captured the important city of Seville and the military there for the putschists on that day . During the night the unions called a general strike.

A race began between the putschists and the workers' organizations to secure the most important cities on the coast of southern Spain against Spanish Morocco. The attitude of the local civil governor as well as the local Guardia Civil and the Asaltos were often decisive. The Republicans achieved successes in Málaga , Almería and Jaén , while the coup plotters Cádiz (with its naval base), Jerez , Algeciras and La Linea fell into the hands. Prime Minister Casares Quiroga resigned on July 19 after his misjudgment of the situation became apparent. His successor, Diego Martínez Barrio , sought to end the uprising by promising the insurgents a political say and the restoration of public order, which the conservative opposition had unsuccessfully demanded in parliament for the previous five months. However, this was replaced after a few hours by the more radical José Giral when efforts to mediate had failed. The new government immediately ordered the fleet to go to the Strait of Gibraltar to prevent the African Army from crossing over. The army was dissolved by decree and weapons were distributed to the workers' organizations.

In the days that followed, each soldier was faced with the choice of which side to fight for. 80% of the lower and middle officer corps , the majority of the NCOs, but only four division generals, decided in favor of the coup . The nationalists were often able to get their way through the arrests of local military leaders and governors who were loyal to the republic, most of whom were shot immediately. In many cities, including Madrid and Barcelona, local barracks were besieged by workers' militias. By the end of July, the coup plotters had gained control of a wide area in northern Spain from the Carlist region of Navarre in the east to Galicia in the west, with the exception of the coastal region from the Basque Country to Asturias . In the south, the nationalist area extended to Saragossa , Teruel , Segovia , Ávila and Cáceres . The cities of Seville , Córdoba and Granada as well as Oviedo and Toledo in the north , as well as the Balearic Islands with the exception of the island of Menorca , were added as (soon connected) enclaves in southern Spain . The coup plotters failed in the provinces of Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona , where 70% of Spanish industry and the majority of the Spanish population were concentrated.

On July 24th, the nationalists of the Northern Army under General Mola proclaimed an opposing government in Burgos , the Junta de Defensa Nacional , chaired by General Miguel Cabanellas . They deliberately left open the question of the form of government they were striving for, in order to keep the groups that supported them (Falangists, Carlist, Alfonsists, etc.) on their side. In the south, General Queipo claimed leadership of the nationalists. Franco was finally able to assert himself as the leader of the nationalist movement throughout Spain in September 1936, without his competitors having forgiven him.

About half of the regular army in Spain took the side of the nationalists, including 10,000 officers, two thirds of the Carabineros (border police) controlled by Queipo , 40% of the Asaltos and 60% of the Guardia Civil . The most important combat instrument of the rebels was the Africa Army with its Moorish mercenaries and the Foreign Legion , plus the Carlist militias ( Requeté ) and the Falange , which until 1937 retained relatively independent command structures. The nationalists received financial and logistical support from Italy and the German Empire at the beginning of the civil war.

The majority of the generals, two-thirds of the navy and half of the air force remained loyal to the republic, but they could not compensate for the lack of an intact officer and non-commissioned officer corps in the crucial first few months. The troops that remained loyal with the paramilitary Guardia Civil and the Guardia de Asalto formed the military backbone of the republic with militia groups of the Social Democrats , the Communists , the Socialists and the Anarcho-Syndicalists at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. The republic also received substantial support from international volunteers.

Course of war

1936

The last hopes for a quick end were shattered on July 21, the fifth day of the uprising, when the nationalists captured the Ferrol naval base in northwestern Spain and captured two brand-new cruisers there. Furthermore, Franco helped the first airlift in history to move troops from the Spanish colonies to the mainland, thus circumventing the republican naval blockade in the Strait of Gibraltar and consolidating the area they control. This encouraged the fascist countries of Europe to support Franco, who had already made contact with the Nazi state and Italy the day before . On July 26th, the Axis powers decided to support the nationalists; help started in early August. The Axis powers gave Franco financial aid from the start.

Despite the government's countermeasures, the coup plotters managed to move parts of the African army (initially around 12,000 men) across the Strait of Gibraltar by the beginning of August. Under Colonel Yagüe , the main force moved north to secure the area along the Portuguese border. This led to the battles of Mérida and Badajoz, among other things . As a result, the victors carried out mass executions of the Republican defenders. Then Yagüe's troops turned east to march on Madrid. After several skirmishes, including the battle of the Sierra Guadalupe and the battle of Talavera , they were still 100 kilometers from Madrid at the beginning of September. At this point Franco intervened personally in the operations: he ordered Yagüe to turn to Toledo , where the siege of the Alcázar of Toledo by Republicans had been taking place since July . With the conquest of Toledo on September 27th and the end of the siege of the Alcázar, the nationalists achieved an important propaganda victory, but they gambled away the chance of an early capture of the capital. Two days later, Franco declared himself Generalísimo (generalissimo) and caudillo (leader).

In the north-east, the Guipuzcoa nationalist offensive began in August to cut off the Basque Country from the French border. The rebels benefited from the French government closing the border in August. The republican coastline in northern Spain was completely isolated by the success of the nationalists until the end of September. The northern army of Molas also carried out independent advances on Madrid, but all of them got stuck in the mountain ranges north of Madrid.

In August, Republican troops from Barcelona attempted to land from Menorca in the Balearic Islands . While Ibiza and Formentera were occupied with little resistance, the attack on Mallorca at the beginning of September failed despite numerical superiority as well as air and sea support. Menorca remained in republican ownership until shortly before the end of the war, while the rest of the Balearic Islands were finally occupied by nationalists and Mallorca served as the base for Italian bombers for attacks on Catalonia until the end of the war.

The nationalists began a new major offensive from the west towards Madrid in October with a power ratio of 1: 3. The increasing resistance by the government, the mobilization of the population and the intervention of reinforcements (including the XI. And XII. International Brigade and the anarchist column Durruti ) brought the advance to a standstill on November 8th. In the meantime, on November 6th, the government had withdrawn from Madrid, out of the combat zone, and into Valencia . In Paracuellos de Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz , the Republicans carried out mass shootings of Franco supporters and Catholics. The battle for Madrid, which lasted until December 1936, resulted in a siege that lasted until shortly before the end of the war .

The Axis powers officially recognized the Franco regime after the liberation of the Spanish national soldiers trapped in the fortress of Toledo on November 18, and on December 23, Italy sent its own volunteers to fight for the nationalists.

1937

With forces reinforced by the Italian troops and colonial troops from Morocco , Franco tried again in January and February 1937 to conquer Madrid, but failed again in several battles around the road to Coruña . One of the first actions of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV) was on February 8, the coastal strip around Málaga during the Battle of Málaga conquered. This led to the Málaga massacre when nationalist air and sea units shelled refugees from Málaga.

Franco planned a large-scale bilateral containment operation against Madrid in February, but it was only partially carried out due to delays in deploying the CTV. In the battle of the Jarama, southeast of Madrid, which lasted until the end of February , the Republicans were able to hold their ground despite heavy losses. When the Italians finally attacked north Madrid the following month, they suffered a heavy defeat in the Battle of Guadalajara . In these battles the Republicans took advantage of the internal lines, which allowed them to quickly move troops to threatened sections of the front.

Franco realized that the war could not be ended in this way and shifted the focus of his warfare to the isolated, still republican coastal provinces in the north. The six-month " War in the North " began. Basque Bizkaia was the first to be attacked from March 31st , with the Condor Legion flying heavy air raids on republican positions and places in the hinterland. Two of these attacks, on Durango and Guernica , are remembered for the indiscriminate bombing of civilians with high casualties. They also had considerable repercussions on international public opinion on the war. On April 28th, Franco's troops entered Guernica , two days after it was destroyed by the Condor Legion. But then the government began to fight back with increasing efficiency.

At the beginning of May there were internal-republican clashes in Barcelona between the now communist-dominated Catalan regional government and the anarchists of the CNT / FAI and the POUM, which clearly weakened the republican side. Prime Minister Caballero , who had resisted the communist appropriation of the army and government, resigned under communist pressure a week after the events. His successor was the socialist Juan Negrín , but the communists became the real power behind the government.

In May and June the government began two offensives on the central front near Segovia and Huesca to force Franco to withdraw troops from the northern front and thus stop their advance on Bilbao . Both failed after initial success. Mola, Franco's deputy commander on the Northern Front, was killed in a plane crash on June 3, and was succeeded by Fidel Dávila . On June 19, Bilbao was captured after the Basque army withdrew.

In early July, the government even launched a strong counter-offensive near Brunete in the Madrid area to relieve the capital and the northern front. However, the nationalists were able to repel them with some difficulty and with the help of the Condor Legion. An offensive to capture Zaragoza at the Battle of Belchite , which began at the end of August, also failed .

After that, Franco was able to regain the initiative. His troops were able to penetrate into Cantabria and Asturias and captured the cities of Santander and Gijón by the end of October , which meant the elimination of the northern front. The nationalists fell into the hands of war industries and coal mines. On August 28, the Holy See recognized Franco under pressure from Mussolini. At the end of November, when the nationalists were getting ominously close to Valencia, the government went to Barcelona.

1938

In January and February the two parties fought for possession of the city of Teruel , with the nationalists finally being able to hold it from February 22nd. On March 6, the Republican side decided the largest naval battle of the entire civil war and sank the heavy cruiser Baleares in the battle of Cabo de Palos . The outcome of the battle had no influence on the course of the war. On April 14th, the nationalists broke through to the Mediterranean. The republican area was thus divided into two parts. In May the government asked for peace, but Franco demanded unconditional surrender , and so the war continued. The government now began a major offensive to reconnect their territories: The Battle of the Ebro began on July 24th and lasted until November 26th. The offensive failed and determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the end of the year, Franco struck back by mobilizing strong forces to invade Catalonia.

1939

The nationalist offensive that began on December 23, 1938 led to the occupation of Catalonia within a few weeks. Tarragona fell on January 15th, Barcelona on January 26th and Girona on February 4th. On February 10, all of Catalonia was occupied. In anticipation of a massacre, around 450,000 people had tried to escape to France despite the cold, snow and constant attacks from the air. The French government opened the border to civilians on January 28 and to members of the Republican armed forces on February 5, who were interned in improvised camps such as Camp de Gurs . President Azaña and Prime Minister Negrín crossed the border on February 6 and 9, respectively. While Negrín immediately returned to the Republican Zone, Azaña resigned as president in France at the end of February.

After the loss of Catalonia, the republic controlled only a third of Spanish territory, but its armed forces were still around 500,000 strong. Negrín, who was only supported by the communists and part of the socialist party, wanted to continue the war until the beginning of a war between the major European powers that he expected. The plan to "integrate" the Spanish civil war into a European war and still win it was thwarted by the governments of Great Britain and France on February 27, when they diplomatically recognized the Franco government.

On 4th / 5th March 1939, parts of the republican army under Colonel Segismundo Casado put in a coup d'état in Madrid against the Negrín government, under the pretext that a Communist takeover was imminent. They were supported by anti-communist anarchists around Cipriano Mera and Eduardo Val and representatives of the right wing of the PSOE around Julian Besteiro . Both Casado and Besteiro were in contact with representatives of Franco's “ fifth column ”, who had given them to understand that a negotiated surrender was possible and that if Madrid were surrendered without a fight, only the communists would be persecuted. In a “civil war within a civil war” that lasted several days and killed around 2,000 people, the Consejo Nacional de Defensa , which they formed, prevailed against the I. Corps, which was commanded by communist officers. Its commander was executed, numerous communists were imprisoned, left in prisons when Franco's troops marched in and then immediately killed by them. A similar revolt in the Cartagena naval base , in which the “fifth column” openly took part, was put down again by Republican troops. However, the fleet settled down to French North Africa , which made the mass evacuation planned by Negrín impossible.

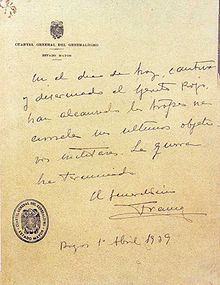

After the Casado coup, the republican resistance collapsed. Soldiers were captured or deserted along the entire front. Some smaller groups went underground to organize a guerrilla war that lasted until 1951 in some areas. Despite the de facto dissolution of the republican army, Franco did not order the general advance of the "national" troops until March 26th. Without encountering organized resistance, they occupied the entire remaining territory of the republic within a few days. Madrid fell on March 27th. On March 30th, Italian troops occupied Alicante , where tens of thousands of refugees had hoped in vain to be evacuated. Negrín managed to escape and formed a government in exile in France ; Casado and some of his supporters were picked up by a British destroyer in Gandía , as agreed with Franco and the British government . A Franco bulletin declared the civil war over on April 1, 1939.

International dimension

The Spanish Civil War had an important international aspect. As it reflected the ideological lines of conflict in Europe and set the continental power constellation in motion, the course of the war and the fate of the republic depended crucially on the attitude of the other European powers. Under the aegis of the League of Nations, they formed the Non-Interference Committee , which met for the first time on September 9, 1936. Although the main actors were formally members of the committee, with the exception of Portugal , which joined a little later, it soon became apparent that the principle of non-interference was not being seriously pursued.

On the one hand, Fascist Italy and National Socialist Germany openly supported the putschists, while the liberal democracies France and Great Britain practiced a policy of non-interference and thus favored the triumphant advance of the insurgents. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, supplied the republic with weapons and advisors until 1938. As a result, she was able to significantly influence the Madrid government and expand the position of the previously insignificant Spanish Partido Comunista de España (PCE). In addition, the Soviet Union decisively promoted the decline of the social revolution. The latter happened out of both power and strategic reasons. The aim was to win the favor of the liberal capitalist powers which Stalin tried to win over to his side in the anticipated conflict with fascism. Spain thus became a military and political laboratory for the simmering systemic competition in Europe, which culminated in the Second World War . The elected Spanish government became an early victim of the appeasement attitude of the leading democracies, which was not least due to an anti-communist calculation. The putschists would never have got this far without the intervention of Mussolini and Hitler, but they were able to avoid being completely instrumentalized by Rome and Berlin.

Another not insignificant element was the economic support of the nationalists by large foreign corporations, especially from the USA and Great Britain, in whose hands large parts of Spanish industry and infrastructure were located. Rio Tinto controlled the mining and ITT owned a large part of the communication infrastructure. The lower financial resources of the nationalists against the republican government were generous foreign loans for the first offset, which as not meeting the procurement of large quantities of war equipment trucks under the embargo or the American neutrality laws were, and allowed oil. Black transactions, such as the delivery of 40,000 bombs by DuPont , were partly carried out via Germany.

The republican side, which faced a materially inferior but better educated opponent, was supported by the Soviet Union with extensive supplies of material and 2,000 armed men. With advanced I-16 fighters and around 600 T-26 battle tanks, it had a long history of superiority in terms of heavy material. The rest of the military equipment, however, consisted largely of a hodgepodge of outdated weapons: ten different types of rifles of different calibers from eight countries of origin, which, because of their age of 50 to 60 years, were already ripe for museums. These weapon purchases were offset against the Spanish gold stocks that were brought to the Soviet Union by the NKVD , with the Soviet Union making a profit of 25% from the exchange rate of the ruble alone.

The extensive support from German and Italian fighter pilots for the national side was of particular importance for the course of the war, although the tide turned after the arrival of the Condor Legion. During the entire war, there were only 806 Soviet machines compared to 1533 German and Italian machines. The other material aid provided by the German Reich and Italy was less than that provided by the Soviet Union, but the number of Italian volunteers in particular far exceeded the military personnel sent by the Soviet Union. The democratic countries of Europe invoked their neutrality, only France opened its border on two occasions to support the Frente Popular with material. The Republic of Poland did not officially support the coup plotters, but it did deliver weapons to them. Polish citizenship was withdrawn from every Pole who joined the International Brigades of the Republic . (This was also the reason why after the Second World War Francoist Spain was one of the few countries that continued to recognize the Polish government in exile after 1945.) The Spanish government eventually had to turn to international arms dealers. The military equipment they used to defend the Second Republic came from over 30 countries, but Franco's captured or otherwise acquired obsolete material was used in the same way as by the Republicans. The reasons for the inferiority of the republican associations are therefore not to be found exclusively in the military equipment, but not least in its use by often inexperienced and poorly trained officers and soldiers.

Supporters of the coup plotters / nationalists

Germany

After an urgent request for help from Franco, Hitler spontaneously supported the putschists with the necessary means. For the Nazi regime, the civil war was a new battlefield in the global conflict against “Bolshevism”. In addition to the openly presented ideological component, there were primarily strategic and military reasons for the Nazi involvement. Spain should not be ruled by any regime that would be hostile to the German Reich. Hitler's visions of war played a role here. This happened against the background that France had also had a Popular Front government since July 1936 , whose predecessor had already made initial rapprochements with the Soviet Union - but this soon came to an end due to British and domestic political pressure.

There were also economic motives: Spain owned a number of raw materials that were relevant to the armaments industry and that they wanted to acquire through an agreement with the Franco regime. The competitor here was Great Britain. Immediately after the putsch, all employees of German corporations left the areas controlled by the republic. They either went to the areas controlled by Franco or left Spain by ship, whereby some of the employees of the IG Farben may have used the armored ship Germany as a means of transport . Probably a total of 16,000 German citizens fought on Franco's side in Spain. Their maximum number was about 10,000. The number of German citizens killed is given as 300.

Financial aid

Germany's financial aid to the Nationalists in 1939 was approximately £ 43,000,000 ( $ 215,000,000). 15.5% of this aid was used for salaries and expenses, 21.9% for arms deliveries and 62.6% for the Condor Legion.

weapons shipments

The very prompt delivery of weapons by sea suggests that weapons were ordered by the putschists in Germany before the military uprising. Just a few days after the military coup, on July 22, 1936, the German steamship Girgenti was searched for weapons by republican forces in the port of Valencia . The German Foreign Ministry protested to the Republican government in Madrid. Shortly afterwards the steamship was chartered by Joseph Veltjens and reloaded on August 22, 1936 in Hamburg with weapons for the coup d'état in the La Coruña region . In addition, on August 14, 1936, Veltjens delivered six He 51 fighter planes to the Spanish general and main actor in the coup, Emilio Mola . During a negotiation with the dictatorial Portuguese Prime Minister A. Salazar on August 21, 1936, Johannes Bernhardt managed to use the port of Lisbon to avoid a blockade of the port of Cadiz by the republican navy. Walter Warlimont , who was initially entrusted with the economic coordination, suggested founding a company based on the coal and steel scheme . As a result of a meeting on October 2, 1936, the Rohstoff- und Wareneinkaufsgesellschaft mbH (ROWAK) was created as a counterpart to the HISMA operating in Spain . Eberhard von Jagwitz , a friend of Bernhardt , became the managing director of ROWAK . Because the putschists did not have enough currency reserves , a clearing system was established with the German Reich in which military equipment was set off against mining concessions, for example. According to the historian Hugh Thomas , Friedrich Bethke traveled to all ore mines, blast furnaces and rolling mills in this region for over 14 days immediately after taking Bilbao in June 1937. In 1937 ROWAK had 73 mining rights, in 1938 there were 135. The mining rights related to strategic raw materials such as iron, copper, lead, tungsten, tin, zinc, cobalt and nickel. Franco later signed six mines over to the German Reich to settle its war debts.

German companies

As a German company, z. For example, the IG Farben several times during the Spanish Civil War amounts to 100,000 pesetas and awarded Franco's military successes with special bonuses. Together with Siemens and other German companies, she supported the Legion Vidal , a medical force of the putschists. In addition, IG-Farben supplied important raw materials for the production of war goods. In addition, the company delivered the electron-thermite stick incendiary bomb B 1 E for the Condor Legion , which was used in the air raid on Gernika and other Basque cities. There is evidence that the company also created blacklists and reports on members of the IG-Farben workforce in the areas of the republic. According to these reports, two-thirds of the workforce were on the side of the Spanish Republic. Those employees who welcomed the Franco coup received instructions on sabotage. Some of these employees even got into management positions, such as Juan Trilla Buxeda , who headed a works council for IG Farben. According to a US government report, a total of 104 people could be identified who worked as informers for IG Farben and other German companies. From 1938 onwards, one of the four world-wide centers of the stage service outside the German Reich was set up in Spain . In June 1938, Hellmuth Heye inspected the sites in Spain that had been shut down in the first years of the civil war.

Hans Eltze organized supplies of war materials for the export cartel, Export Association for War Equipment .

Fire magic company

The first purely military support for Franco by National Socialist Germany took place at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. On July 27, 1936, in order to organize the military aid for Franco and to coordinate the various branches of arms, the special staff W was formed under Hermann Göring , which was headed by Helmut Wilberg and Erhard Milch . The first project of the special staff W was named after the 3rd act, 3rd scene from Wagner's Walküre , Fireworks Magic Company . It was the airlift with planes of the German Lufthansa , through which troops of the putschists, including foreign legionnaires , were transferred from Spanish Morocco to the mainland to Cádiz and Málaga . The relocation lasted from July 28 to October 1936, with 20 Ju 52s transporting around 14,000 Foreign Legionnaires and 500 tons of material in more than 800 flights. The German Reich sent six Heinkel 51 fighter planes as escort . The technical coordinator of the airlift on Franco's side was the German captain Heinichen.

In addition, the German armored ships Deutschland and Admiral Scheer provided escort protection for nationalist ships that were transporting troops from Spanish West Africa to southern Spain across the Strait of Gibraltar . Without this intervention, the military coup would presumably have failed in the first few days. One of those responsible was Johannes Bernhardt . He also organized tetraethyl lead to make aviation fuel from Portugal, Gibraltar and Tangier . To further support the coup General Franco, Hitler sent Wilhelm Faupel , a former military advisor in Argentina and general inspector of the Peruvian army, as chargé d'affaires in the Reich government . The German military aid provided was intended exclusively for Franco's Spanish Legion .

Legion Condor

On November 16, 1936, the first 5,000 German soldiers and on November 26, 1936 another 7,000 of the Condor Legion arrived in Cádiz . The Condor Legion, which was sent to Spain and officially only consisted of volunteers, already had 100 aircraft after a few months. Despite the German signing of a non-intervention agreement in September 1936, the Condor Legion intervened in all important battles from 1937: Bilbao , Brunete , Teruel and at the Ebro-Bogen . The air raid on Gernika on April 26, 1937, in which the religious capital of the Basque Country was almost completely destroyed, was of particular - also symbolic - significance . The Condor Legion was also involved in the Malaga massacre , in which around 10,000 people were killed. In January 1937, the Condor Legion was also reinforced by a tank division with 100 tanks of the Panzerkampfwagen I type under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma , but these were only used for training purposes. During the Spanish Civil War, the Condor Legion had no problems with the supply of petroleum products, as Royal Dutch Shell , Texas Oil Company and Standard Oil Company supplied. In addition to the support of Franco by the Condor Legion and motorized units, Germany regularly supplied weapons, ammunition and other war material, which were loaded onto civilian cargo ships in Hamburg for camouflage. The first civil freighters, the Cameroon and Wigbert , arrived on August 22, 1936.

Navy

During Operation Ursula (named after Karl Dönitz's daughter ), under the command of Hermann Boehm , the Navy dispatched the U- 33 and U-34 submarines to the Mediterranean on November 20, 1936 . In order to keep the mission a secret, all sovereign symbols of the submarines were made unrecognizable. The aim of the operation was to cut off the Republican supply routes. The submarines reached the Mediterranean on the night of November 27-28 and took over patrols from Italian submarines that were already blocking Republican ports. At the end of November, the two German submarines were in the sea area between Cartagena and Almería .

On December 1, 1936, the German submarines launched an underwater war against the Spanish Republic in violation of international law . U 33 tried to torpedo a convoy of ships on December 2nd. Due to a leading Republican destroyer, the convoy could not be torpedoed. The next day U 33 tried to attack the convoy again. This attack was disrupted by the presence of a British destroyer. After a miss shot at a freighter, U 34 broke off the attack. Franco's fleet chief Admiral Moreno knew of another, for the 7th – 9th. December planned convoy with four republican steamers and urged the German Reich to attack again. On December 8, U 34 fired its third torpedo against a destroyer accompanying the convoy, but did not hit it. On December 9, 1936, the two submarines were ordered to leave the operational area within three days. On the voyage into the Atlantic Ocean , Kapitänleutnant Grosse of U 34 spotted the Republican submarine C-3 in front of the port of Malaga on December 12 and sank it. On December 13, 1936, the two German submarines passed the Strait of Gibraltar unseen . The return of the submarines to Wilhelmshaven in December marks the official end of Operation Ursula . Various reasons, such as the difficulty of clearly identifying targets and concerns about the exposure of the mission, justified the termination of Operation Ursula . Captain Harald Grosse of U 34 was the only member of the Navy to receive the gold Spanish cross in 1939 . The commander of U 33, Kapitänleutnant Kurt Freiwald , only the very often awarded Spanish Cross in bronze.

In February 1937, during the Battle of Malaga , the Admiral Graf Spee shelled Malaga. With naval forces from Great Britain, Italy and France, the Navy also participated in the international naval blockade to enforce an arms embargo against Spain, with a coastal area in the Mediterranean between Almería and Valencia . In fact, this mission served to support the coup d'état Spanish nationalists under Franco. The commanders of the naval forces were Wilhelm Marschall and Rolf Carls . The navy dispatched the armored ships Admiral Scheer and Germany . The light cruiser Cologne and four torpedo boats were also sent to Spain by mid-October . On May 29, 1937, the ironclad Germany was bombed and damaged off Ibiza . The attack by the Republican Air Force left 31 dead and 75 wounded. After the attack, the Admiral Scheer was ordered to carry out a retaliatory strike against the fortified port of Almería, the berth of the republican fleet. Since many grenades missed their targets and hit the city, the operation was not very successful. 21 residents were killed in the bombardment and another 55 were injured. Between 1936 and 1939, twelve torpedo boats, six light cruisers and three ironclad ships were involved in the operations of the Kriegsmarine.

Immediately after the bombing of Republican planes against the ironclad Germany on May 29, 1937, four submarines of the “Saltzwedel” submarine flotilla were sent into Spanish waters to take part in international maritime control . Their control area was the Spanish Atlantic coast . One of these four submarines, U 35 , sighted a convoy off Santander on June 3, 1937 , which was accompanied by two Republican destroyers. When one of the destroyers recognized the submarine and turned away, U 35 appeared and tried to sink the destroyer.

After the German cruiser Leipzig was attacked with four torpedoes on June 15, 1937, Hermann von Fischel prepared a new secret submarine operation in the Mediterranean, an area in which German submarines were not allowed to stay. Before crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, U 28 , U 33 and U 34 painted over their number and neutrality symbols. At that time, U 14s were already in the Mediterranean without a license plate or flag. The order to attack Republic ships was not given for unknown reasons. The German Navy officially ended its activities in Spain at the end of 1938. U 35 Ferrol was the last submarine to leave the Mediterranean on January 5, 1939 in the direction of Brunsbüttel .

Concentration camp / Gestapo

In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the putschists set up a concentration camp based on the German model in Miranda de Ebro . This camp was run by SS and Gestapo member Paul Winzer . According to a Gestapo report from August 1939, Gestapo officials were in Spain interrogating prisoners . After the police agreement of July 31, 1938 between Heinrich Himmler and Severiano Martínez Anido , SS-Sturmbannführer Winzer set up an SD network in Spain in addition to the existing defense network. Numerous SD employees were employed by German companies in Spain. The cooperation also included the mutual extradition of "political criminals". In 1940 Heinrich Himmler also visited Spain with Karl Wolff . The meeting had two main goals: to repatriate the German prisoners of war and to get hold of potential Allied spies in Spain. Heinrich Himmler also visited the Miranda de Ebro concentration camp near Burgos .

Propaganda Aid

The German Reich also provided propaganda aid. The Germans set up a press and propaganda office in Salamanca , which conveyed the tried and tested techniques of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda to the Franco regime . One of the tasks of the Propaganda Bureau was the mediation of the Spanish events in the German Empire.

Secret operations

An estimated 700 Irish volunteers made their way to Spain prior to the Irish government's ban on participating in the war. The shipping of the Irish volunteers from the Irish Brigade was organized by Joseph Veltjens , who acted on behalf of the German Reich .

diplomacy

After Franco raised himself to head of state, Germany and Italy recognized the military coup as the legitimate government of Spain on November 18, 1936. Chargé d'Affaires of the Reich government in Salamanca was Wilhelm Faupel . In this role he was responsible for relations with Franco . From February to October 1937 he was the ambassador of the German Reich in Spain . Furthermore, Lieutenant Colonel Walter Warlimont was commanded to Spain as the Military Plenipotentiary of the Reich Minister of War. In the Nuremberg trials, Göring stated that he had urged Hitler to test the new air force. The Luftwaffe supported all military operations of the rebels from 1937 on . The most famous case is the city of Gernika . The bombing of the city is an example of the devastating effects of area bombing.

Italy

In addition to the German Reich, Italy also interfered in the Spanish war, and to a far greater extent than the German side. Mussolini's most important goal was to make impossible an alliance he feared between France and Spain, both of which were led by left-wing governments in the summer of 1936, and, conversely, to integrate a right-wing government led Spain into its own zone of influence. He justified the intervention in Spain with the same “lie” with which the Spanish generals had justified their coup - Spain was facing a “communist takeover”. The civil war in Spain accelerated the merging of the two fascist states ( Axis powers ). On August 4, 1936, the Italian General Roatta and the head of the German foreign secret service Admiral Canaris met in Bolzano for an initial discussion about mutual support measures for the putschists.

In Rome, unlike in Berlin, they knew beforehand about the intentions of the Spanish generals. Since 1931, Italian authorities had financially promoted all major currents of the anti-republican right. At the end of March 1934, Mussolini had negotiated directly with a delegation of Spanish monarchists and military officials in Rome. Members of the Carlist militia , whose around 30,000 members in Andalusia and Navarre played an important role in the uprising in July 1936, received military training in Italy - disguised as " Peruvian officers". The actual extent of Italian arms deliveries prior to the coup is controversial; In March 1934, Mussolini had promised 20,000 rifles and 200 machine guns that were to be smuggled in via Portugal.

Since the putschists had expected immediate success, no prior arrangements had been made about support measures. However, on July 19, 1936, Franco sent the right-wing journalist Luis Bolín to Rome to first ask for transport planes. In return, he promised a close relationship between Spain and Italy in the future. Mussolini, however, held back more than a week with concrete promises until he had certain information at the end of July that neither Britain nor France (under British pressure and in the face of numerous sympathizers of the coup plotters in the press and the army) would support the Spanish republic. Mussolini and his foreign minister Ciano , conversely, were convinced that Italian support for the insurgents had the “covert approval” of Great Britain, which is why the Soviet Union would not dare to intervene in favor of the republic. As a first aid measure, twelve repainted transport and bomber aircraft of the type SM.81 flew from Sardinia to Spanish Morocco on July 30, 1936 , where the crews received uniforms from the Spanish Foreign Legion and placed themselves under Franco's command.

On November 18, 1936, Italy (along with Germany) recognized the Burgos-based junta of the putschists as the legitimate government of Spain. From then on, Italy was de facto at war with the Spanish republic. After Franco failed to capture Madrid and the insurgents faced a serious military crisis, Mussolini decided to show presence with a large contingent of regular troops. In December 1936 the first major Italian unit arrived under the command of General Mario Roatta. The "volunteer associations" of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV) reached a troop strength of 80,000 men by April 1937. About 6,000 of these belonged to air force units, 45,000 to the army and 29,000 to the fascist militias. In addition, there were a total of 1,000 aircraft, 2,000 artillery pieces, 1,000 armored vehicles and large quantities of machine guns and rifles in the course of the war. Mussolini also provided Franco with four destroyers and two submarines. The material, which cost around 6 billion lire, was either lost or remained in Spain after the war, which, among other things, meant that Italy could not dress and arm all drafted recruits at the beginning of the Second World War.

Most of the members of the Italian units had actually volunteered, not least because the service in Spain was extremely well paid. Around 3,200 of them were killed in the fighting. Although the defeat of the CTV in the Battle of Guadalajara is remembered to this day, the Italian troops and planes played an important role, especially in the first twelve months of the war: They took part in the airlift from Morocco to Spain, were expelled the republican navy from the Strait of Gibraltar captured Málaga in February 1937 and ensured the numerical preponderance of the attackers during the campaign to occupy the republican territories in the north, which lasted several months . Italian bombers flew dozens of attacks on Barcelona and Valencia from Mallorca until 1939 . In the three heaviest attacks from 16. – 18. In March 1938, between 500 and 1,000 people were killed in Barcelona. Over 200 people died in an air raid on Granollers on May 31, 1938. Italian planes and submarines attacked ships with war material for the republic along the Spanish Mediterranean coast until the end of the war and sank many of them.

Portugal

When civil war broke out in Spain in 1936, the Portuguese " Estado Novo " supported the Franco coup. In addition, the nationalists were supplied with war material via Portugal. Already in the first weeks of the war a legion, the Legion Viriato , was to be set up and sent to Spain. After pro-republican unrest in Portugal, the Salazar government decided not to intervene directly in the war. Before the Legion could even be recruited, it was dissolved. Under the guise of neutrality, the Portuguese government authorized the recruitment of volunteers for the Spanish Legion . Portuguese volunteers, who were recruited through a large-scale publicity campaign and fought for the Spanish nationalists, were therefore referred to as Viriatos. Up to 12,000 Portuguese volunteers fought on Franco's side during the war. During the Spanish Civil War, in contrast to the fascist states of Germany and Italy, there was never an autonomous Portuguese command structure. In the victory parade of Franco in Madrid on May 19, 1939, the Portuguese Viriato Legion and the German Condor Legion brought up the rear.

As early as March 1939, shortly before the end of the Spanish Civil War in April 1939, Portugal signed a friendship and non-aggression pact with Spain, the Bloco Ibérico .

Ireland

During the Spanish Civil War, an estimated 700 Irish volunteers fought on the Franco side in the Irish Brigade, led by Eoin O'Duffy . On December 12, 1936, Joseph Veltjens shipped a total of 600 Irish volunteers from Galway to the Spanish naval port of El Ferrol on behalf of the German Empire . After the shipment, the volunteers were given military training in Cáceres , Franco's headquarters. The Irish became part of the XV Bandera Irlandesa del Terico of the Spanish Legion . With its strength, the Irish Brigade was the largest foreign unit in the Spanish Legion. On February 17, the brigade was moved to Ciempozuelos , a place 35 kilometers south of Madrid on the Jarama River . The Battle of the Jarama was the last battle the Irish Brigade took part in. In June 1937 they were shipped to Ireland via Lisbon . Of the estimated 700 Irish volunteers, 77 brigadists died, according to unofficial information.

Supporter of the Spanish Republic

International militiamen

The first international militiamen at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War were mainly participants in the People's Olympiad in Barcelona and political emigrants who lived in Spain. These were 300 militiamen who organized themselves into groups (Spanish: Grupo) after the military coup in Barcelona . They formed groups of international militiamen with the first international volunteers who came to Spain via France. These groups went into hundreds (Spanish Centuria) who fought primarily on the Aragon front at the beginning of the civil war . Communist international volunteers fought mainly in PSUC militia units, socialist international volunteers mainly in POUM militia units, and anarchist ones mainly in the militia units of the CNT and FAI . There were many famous people among the international militiamen, such as George Orwell and André Malraux .

International Brigades

On August 3, 1936, the Comintern passed a general resolution to set up a communist-led international brigade. It was not until September 18, 1936, after Stalin had made a decision, that a meeting was called in Paris in which Eugen Fried announced Stalin's decision to set up an international brigade. As a result, communist parties from various countries organized the recruitment of volunteers. At the time of greatest participation, the International Brigade numbered 25,000 fighters. A total of 59,000 people served in the International Brigades. The largest contingents were French, Germans and Italians.

Soviet Union

In 1935 the Soviet Union had given up its course of confrontation, which had been exported to the West via the Comintern , and was now seeking an alliance with the European democracies against emerging fascism ( popular front policy ) , switching to the geostrategic defensive . Open support for the republic therefore only got rolling when it became clear that the Western powers would not campaign for the Spanish republic and that the smaller fascist states had long since brought their resources into play. Later attempts by the Soviet Union to persuade London and Paris to take action against Italy and Germany also failed and increasingly isolated Moscow. On October 28, 1936, the Soviet ambassador Iwan Maiski in London, who was also a representative on the non -interference committee, declared that the Soviet Union was no more bound by the non-interference agreement than Germany, Italy and Portugal.

As early as August 3, 1936, the Comintern passed a general resolution to set up an international brigade . But it was not until September 18, 1936, after the hitherto cautious Stalin had made a decision on this matter, that a meeting was called in Paris in which Eugen Fried announced Stalin's decision to set up an international brigade. As a result, communist parties from various countries organized the recruitment of volunteers.

The Soviet Union and Mexico were the only significant allies for Madrid; the republic thus became de facto dependent on Moscow. The almost exclusive Soviet involvement also had serious domestic political consequences for the republic. The rise of the Spanish communist party PCE followed . As a result of the influence of the Soviet Union, the number of PCE party members grew from 5,000 to 100,000 to 300,000 within one year from 1936 onwards. The PCE was mainly joined by Spaniards who were hostile to the moderate socialist parties of the Popular Front government. Above all, it gained members in the middle class and the petty bourgeoisie , who feared losing their privileges.

The military was completely dominated by the communists and their political commissars because of the Soviet arms shipments. With the help of General Commissioner Alvarez del Vayo , by the spring of 1937 it was possible to penetrate the military system to such an extent that 125 of the 168 battalion commissioners were partisans of the PCE and PSUC or members of the Union of Communist Youth Associations of Spain .

The Soviet authorities tried to keep the number of Red Army specialists deployed in Spain as secret as possible. That is why Soviet experts signed up as volunteers with the International Brigades. According to historian Antony Beevor , the Soviet Union dispatched 30 Soviet officers to serve as commanders in the International Brigades. For example, the Soviet major Ferdinand Tkachev commanded the Palafox battalion . Three of the four companies were under Red Army lieutenants. The exact number of Soviet specialists is given as a maximum of 2,150, with no more than 800 staying in Spain at any time, including 20 to 40 NKVD employees (including the controversial journalist Mikhail Jefimowitsch Kolzow ) and 20 to 25 diplomats. The top Soviet military advisor in Spain was Jan Bersin . In addition, members of the International Brigades were trained in a training center with a capacity of 60 infantry officers and 200 pilots in Tbilisi .

However, what the government troops needed most in the early months of the war were weapons, ammunition and other equipment. As with the International Brigades, Stalin was noticeably reticent on this issue, probably for fear of international entanglements. Urgent calls for help from the Giral government , which were issued in July, were not answered. Only oil should be offered to the Republicans at a reduced price in unlimited quantities. The first Soviet arms deliveries finally arrived in Spain in October 1936. The delivery included 42 Polikarpow I-15 biplanes and 31 Polikarpow I-16 fighters. On October 29, 1936, Soviet Tupolev SB-2 bombs attacked Seville , and on November 3, the first Polikarpov I-16s could be seen over Madrid. However, the Soviet Union barely granted the Spanish government any loans, and the arms deliveries were well paid for with significant parts of the Spanish gold treasure. The Soviet arms deliveries were organized by the Soviet naval attaché in Spain Nikolai Kuznetsov . The Soviet ships ran under a false flag . At the height of Algeria to the north with a course for the Spanish Mediterranean coast, 48 hours before the port of destination, the staff of Kuznetsov organized an escort of Republican warships. The first freighter, the "Campeche", reached Cartagena on October 4th, 1936 and the freighter "Komsomol", loaded with T-26 tanks, reached the port of Cartagena on October 12th. According to its own information, the Soviet Union delivered from October 1936 to March 1937: 333 aircraft, 256 tanks, 60 armored vehicles, 3,181 heavy and 4,096 light machine guns , 189,000 rifles, 1.5 million grenades, 376 million cartridges , 150 tons of powder and 2,237 tons of propellants and propellants Lubricants.

With the Soviet arms deliveries, the balance of power shifted towards authoritarian power control by the Soviet-dominated PCE. Due to the growth of Stalinist influence on republican Spain, members of the Soviet secret service NKVD and members of the Comintern were able to unleash a massive wave of terror against the anarchist CNT , the Marxist POUM or real and supposed Trotskyists . They were defamed as "fascist-Trotskyist spies", as " Franco's fifth column " or as defeatists . The clashes culminated in the May events of Barcelona, a "civil war within a civil war" - an internal conflict that further weakened the republic. In the name of anti-fascism , the Soviet secret service NKVD murdered unpopular fighters who actually or supposedly deviated from the Moscow line.

The Soviet military secret service GRU carried out acts of sabotage in Spain in addition to pure reconnaissance missions in the hinterland of the nationalists . Those responsible were Alexander Orlov and Hajji-Umar Mamsurow . After the Spanish Civil War, Orlov claimed that 1,600 partisans were trained in training centers . According to him, 14,000 Republicans fought as partisans.

In research it is still unclear why Stalin almost completely stopped his support from 1938 onwards. All in all, one can only speculate about Stalin's intentions in connection with his policy on Spain. The Soviet engagement never reached the level, both materially and personally, that would have been necessary to help the Republicans to victory, and was possibly only intended to prevent a complete loss of face for the Soviet Union in the global communist movement. According to their own account, a tightening of the blockade made deliveries largely impossible.

The military part of the Soviet Union was further denied in communist depictions until the 1950s. Only since the XX. At the CPSU party congress in February 1956, the approach changed. Soviet officers and diplomats who had fallen victim to the Stalin purges as former Spain fighters were posthumously rehabilitated.

Mexico

The Republican government also received aid from Mexico . Unlike the United States and major Latin American states, the ABC states and Peru , the Mexican government supported the Republicans. Refusing to follow the September 1936 non-intervention agreement, Mexico backed the Republicans with over $ 2 million and 20,000 rifles with 20 million cartridges. Mexico's most important contributions to the Spanish Republic were diplomatic aid and the reception of around 50,000 Republican refugees. These included many Spanish intellectuals and orphaned children from Republican families.

Neutral states

Great Britain

Great Britain has played an important role in the Mediterranean region since the beginning of the 18th century, for example in the War of the Spanish Succession . Because of the problems of the Empire and the decline in its military strength after World War I , it was decided to focus on the continent. In addition, the Spanish republic, founded in 1931, was not very respected by the British or US elites , as they were suspected of socialist tendencies and the social revolution directly affected the interests of British businessmen.

In addition, there were some traditional stereotypes about the supposed nature of "the Spaniards", who even politically more liberal and left-wing forces in Great Britain attested to a certain hot-bloodedness, aggressiveness and recklessness. The conservative elites, for example, had sympathy for the putschists because they left property relations intact. The policy of non-interference was intended to "neutralize" Spain, limit the conflict to the Iberian Peninsula, and make the country neither "communist" or a military asset for the fascist rivals who questioned the continental order. Franco accommodated the British here by declaring Spanish neutrality in 1938 as a precaution in a possible European conflict. Despite significant tensions, diplomatic and economic relations between Great Britain and the Franco regime intensified, especially after the capture of the Basque Country.

France

60% of all foreign investment in Spain came from France. In Paris in July 1936, the socialist government of Léon Blum ruled a similar government, so that the neighboring country was an obvious choice as an ally for Spain. In fact, the Third French Republic , which was influenced by a pacifist trend, was split in a similar way to the Spanish one and was therefore greatly weakened. Large parts of the bourgeois camp were clearly on the side of the putschists. In addition, a small detachment of right-wing French fought in the Spanish Foreign Legion under Franco . The left, on the other hand, sympathized with the legitimate Spanish government . In order not to have to fight the civil war in its own country, Paris quickly refrained from providing open material aid, especially since it was closely tied to Great Britain in terms of foreign policy. The controversy cut across government and divided all public opinion. It reflected - more so than in Great Britain - the social polarization in the country. In addition to the strategic weakness, this internal blockade ultimately made it impossible for the Blum government to come to the aid of the neighboring parliamentary republic.

Repression and political assassinations

All historians agree that the Francoist repression, which was primarily directed against Republican soldiers, trade unionists and members of left-wing parties , cost significantly more victims than the Republican repression, which was mainly directed against clergymen, members of the right-wing parties and Falangists. The Church estimates that nearly 7,000 clergy were killed between 1931 and 1939. Shootings were the order of the day on both sides, especially in the first few weeks and months of the war, and various Red Cross agreements were later reached. However, the information on the number of murdered varies widely; for the nationalist zone the estimates have so far been between 75,000 and 200,000 (currently the number of those "disappeared" is being revised upwards significantly, so that this will also have a significant impact on the total number of victims), in the republican zone between 35,000 and 65,000 victims. Antony Beevor wrote in The Spanish Civil War :

“The killing was not done in the same way on both sides. While the cruel purges of 'Reds and Atheists' in the nationalist area continued for years, the acts of violence on the part of the Republicans were mainly spontaneous and hasty reactions to suppressed fears, reinforced by the desire for retribution for atrocities committed by the enemy. "

However, César Vidal, a prominent representative of Spanish historical revisionism , rejects this assumption and points to the active and ongoing involvement of Republican institutions in crimes committed on Republican territory.

In the Málaga massacre of the fleeing population from Málaga , around 10,000 people were murdered by the nationalists. In the Francoist concentration camps established during the war, medical experiments based on racial ideology were also carried out on the republican prisoners - with National Socialist support - to investigate alleged physical and psychological deformations that occurred in supporters of "Marxism". After the war, the entire Republican army and other well-known personalities were taken prisoner, which again cost many lives. After the end of the war, a total of around 275,000 people were trapped in mostly unworthy conditions, for example in bullring and football stadiums. By the late 1940s, the number had dropped to about 45,000.

In February 1939 there were almost 500,000 war refugees. Initially, they were mostly interned in the south of France. More than half returned to Spain in the next few months. Some politically persecuted Spaniards emigrated to different countries, especially to Latin America. About 150,000 remained in France. Several thousand Spaniards were sent as prisoners of war to various main camps after the German Wehrmacht marched in, and from August 6, 1940 to the Mauthausen concentration camp . There were over 7,000 Spanish prisoners there, 5,000 of whom died. Some Spaniards were extradited from France to Franco by the Gestapo , such as Companys , Zugazagoitia or Cruz Salido . Others, like the former head of government Francisco Largo Caballero , were deported to other German concentration camps, where there were also several hundreds of Spaniards arrested in France for their anti-fascist resistance.

Until about 1945 mass shootings took place as the execution of the death penalty imposed by courts-martial , but often also "spontaneously" and without a verdict. The repression of these years, the investigation of which is far from over, is believed to have fallen victim to well over 100,000 opponents of the regime.

Until recently it was assumed that at least 30,000 to 35,000 murdered supporters of the republic, who had been buried outside the villages and towns, are still lying in mostly unmarked mass graves to this day . According to the latest research results, the number is likely to be significantly higher; for Andalusia alone, the number of "disappeared" Republicans has recently been given as 70,000. Most recently, the survivors' associations cited the specific number of 143,353 "disappeared" as a provisional interim balance. In a report by Deutschlandfunk from September 2008, it says:

“Less than ten years ago, the number of those shot and disappeared was put at around 30,000. Historians recently suspected 100,000 victims. The first attempt at an actual and thorough census has now been presented. It was a shocking, if only provisional, number. Empar Salvador, spokeswoman for an association of survivors' associations that have been researching and digging for mass graves in all regions of Spain for years, names 143,353 cases. "

Since 2000, the organization ARMH ( Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica , Association for the Reclamation of Historical Memory ) has been striving for exhumation and dignified reburial. One of the probably largest mass graves was discovered in 2003 in El Carrizal near Granada; 5,000 execution victims were buried there. Since 2007 a law of the socialist government ( Ley de Memoria Histórica ) provides that the municipalities support the private initiative of the exhumation work. In many municipalities and regions, even today, the conservative Partido Popular opposes the finding and reburial of the murdered Franco victims. The Rajoy government withdrew the budget from the law in 2013 and thus de facto overruled it.

Social revolution

Two eyewitnesses on their impressions of the social revolution:

“And then, when we turned the corner into the Ramblas (the main artery of Barcelona), a huge surprise came: suddenly the revolution spread before our eyes. It was overwhelming. It was as if we had landed on a continent that was different from everything I had seen before. "

“You felt like you had suddenly emerged in an era of equality and freedom. Human beings tried to behave like human beings and not like a cog in the capitalist machine. "