Max Bair

Max Bair (born April 28, 1917 in Puig, Tyrol ; † July 25, 2000 in Berlin ) was originally a small farmer, then an interbrigadist in the Spanish Civil War , communist party cadre in the Soviet Union and an Austrian resistance fighter against National Socialism in Slovenia . After the end of the Second World War, Bair was the first state secretary of the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) in Tyrol. After moving to the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and completing an economics degree, he became an employee of the State Planning Commission (SPK) in East Berlin . Bair achieved particular fame as the protagonist of the literary report The Three Cows by the famous journalist and writer Egon Erwin Kisch .

biography

Childhood and youth in Tyrol

Bair grew up as the eldest of three siblings in a family of small farmers in Puig, a small hamlet between the communities of Steinach and Matrei am Brenner . Not uncommon for the time, he had to work in his parents' farm as a child, which is why he was only able to complete two classes of primary school. Bair achieved good school results early on; a higher education at a seminary, as it had been promised by the local pastor, was denied the boy, because his parents could not do without him at court.

At the age of sixteen Bair was both parents for following the early death orphans . He then inherited the parental farm together with his sister. For legal reasons, an uncle was appointed as guardian up to Bair's legal age to manage the property in the interests of the heirs. In the meantime, Bair worked as a lumberjack for several years.

In 1937, at the age of 20, Bair took over his farm in debt. In order to pay off part of the costs, he then took in the worker Johann Winkler as a "boarder". It was through Winkler that Bair came into contact with socialist ideas for the first time , after he had previously briefly been a member of the Catholic - Austro-Fascist “ Ostmärkische Sturmscharen ”.

A few months later, in June 1937, Bair, together with Winkler and two other workers from the area, Ludwig Geir and Stefan Zlatinger, decided to travel to Spain to take part in the civil war as a member of the International Brigades . In order to finance the trip for all four, Bair sold his three cows. Although economic hardship (see global economic crisis ) and lack of future prospects may have favored Bair's decision, he himself cited his disappointment with the moral promises of the Catholic Church as the decisive reason in later interviews:

“I was brought up very strictly Catholic and took the Ten Commandments seriously. But the comparison with real life has made me doubt their correctness. I couldn't believe what the church said anymore. Coming to terms with my doubts was very difficult for me and I felt very anxious for a long time. I came to the conclusion that something had to be changed in the world, and finally I got rid of religion and got rid of these feelings of fear. Nobody could help me. Workers who I later took on as boarders opened up a new world for me. They made me believe in a better society again. That's why I went to Spain to fight for it. "

Spanish Civil War

With a travel ticket for the world exhibition , Bair and his three companions traveled by train from Innsbruck to Paris . There he registered as a volunteer with the International Brigades in a party office and was transferred to Spain via the Pyrenees in a volunteer transport after just a few days .

After a short training, Bair, like Zlatinger, Winkler and Geir, was integrated into the 11th International Brigade, 4th Battalion (also called Battalion 12 February ) and was promoted to sergeant during his deployment in the Battle of Brunete . At Brunete, Bair also met the writer Egon Erwin Kisch for the first time.

On August 24, 1937, Bair was seriously wounded by a sniper while on patrol near Quinto . During a stay of several months in a hospital in Benicasim , the acquaintance with Egon Erwin Kisch continued, who documented the life story of Bair in writing and published it in the spring of 1938 as a brochure and as an article in the Moscow exile magazine Das Wort .

Stylized in literary terms, Bair then briefly achieved relative fame among the militiamen. As early as April 1938, however, Benicasim was captured by General Franco's opposing troops , and Bair (who was then on a short stay in Barcelona ) was initially evacuated to Catalonia and finally to France in the summer of 1938.

Exile in France and the Soviet Union

In Paris, Bair - who had become a member of the Communist Party of Austria while still in Spain - lived briefly on donations for former Spain fighters, but soon got a job as a milker on a farm in the central French department of Corrèze through Kisch's mediation . In the spring of 1939 - a few months before the start of the Second World War and the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin Pact - Bair finally managed to emigrate to the Soviet Union . There he was able to stay at a spa for convalescence , employment in industry and finally basic political and military training for a planned partisan deployment in the war against National Socialist Germany . Bair's years in the USSR were preceded by a Russian translation of “Drei Khe”, published by Willi Bredel in Moscow in 1939.

Partisan deployment in Slovenia and return to Austria

In October 1944, Bair was sent from Moscow to Slovenia, where he was appointed commander of the 1st Austrian Freedom Battalion, but as such did not take part in combat operations. Soon after his arrival in Slovenia, Bair was seriously wounded again by an assassination attempt and was de facto incapable of working until the end of the war in 1945.

After the liberation of Innsbruck , Bair was appointed State Secretary in Tyrol by the Central Committee of the KPÖ in the summer of 1945 ; eight years after his sudden departure from Tyrol, however, he was unable to gain a foothold there. Social ties were broken, and as state secretary of the KPÖ - which remained an isolated political force in Tyrol - Bair resigned after a short time due to a lack of experience and contact with local party members. In 1947 he sold his farm in Puig, moved to the former Soviet occupation zone in Vienna , where he completed his high school diploma .

In April 1949 Bair was arrested in Salzburg by the US secret service CIC for allegedly helping to deport workers to the Soviet zone and held in a secret prison in Hallein for over 11 months. Bair's arrest turned into a state affair. The National Council dealt with the matter, the party organ of the KPÖ, the popular vote reprinted the "Three Cows"; Conservative newspapers, for their part, raised the mood against the “Bolshevik kidnapper”.

Emigration to the GDR

After his release on bail in April 1950, Bair returned to Vienna. In the summer of the same year, under the impression of the espionage affair, he finally took the opportunity to emigrate to the GDR together with his wife Elisabeth Morawitz (1924–2019) under the name “Martin Jäger” . In the Brandenburg forest of Zinna , Bair then completed a degree in economics. In the mid-1950s he finally moved to East Berlin, where he worked as a member of the State Planning Commission (SPK) and was promoted to head of department for the integrated data center. Bair was for his activities in the GDR a. a. Awarded the Patriotic Order of Merit and the Labor Banner .

After his retirement in 1977, Bair took part in contemporary historical work in Vienna in the context of the KPÖ, with journalists also completing his personal story in several newspaper reports. After the collapse of the GDR, Bair stayed in Berlin. He died there in 2000 as a married father of two daughters and a son from his first marriage. Gerhard Schürer , who had been head of the State Planning Commission for many years, was a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the SED and Bair's superior, gave a commemorative speech during the funeral ceremony .

reception

The literary report by Egon Erwin Kisch achieved international distribution shortly after its publication in the spring of 1938, mainly through its second publication in the German exile magazine Das Wort and translations into English (1939) and Russian (1939). After the end of the Second World War, the text was published by the KPÖ's Globus Verlag (1948). It was then continuously reissued by several GDR publishers until the late 1980s and translated into Slovak (1951), Czech (1955) and Serbo-Croatian (1958). Kisch's report appeared for the first time in a Tyrolean regional medium in 1980 with publication in the left-alternative Gaismair calendar .

The Berlin journalist Klaus Haupt published the first details about Bair's life after the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1982 in the daily newspaper Neues Deutschland . In the years that followed, several German, Austrian and Tyrolean newspaper journalists completed Bair's biography in various press articles. Since 2003, Bair's life has also been recorded in biographical lexica on Austrian and Tyrolean Spanish fighters.

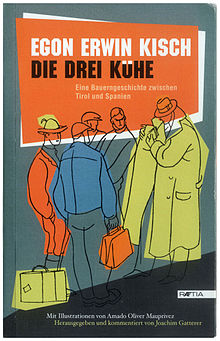

In 2012 a comprehensively commented new edition of the illustrated first edition of Kisch's report was published. In the afterword by the editor Joachim Gatterer, in addition to the overall biography of Bair and the historical background, the significance of the text in terms of literary history is presented in detail for the first time. Around the new edition, in January 2016 - 79 years after the story began - a book presentation of Kisch's report took place for the first time in the Tyrolean Wipptal. a. a daughter and a granddaughter of Bairs from Berlin took part.

Literature (chronological)

- Egon Erwin Kisch : The three cows. A peasant story between Tyrol and Spain , Amalien-Verlag, Madrid 1938, 48 pages [with illustrations by Amado Oliver Mauprivez].

- Klaus Haupt: Egon Erwin Kisch and "The Three Cows" , in: Neues Deutschland , April 30, 1982, p. 12.

- Klaus Haupt: One pointed at me and Kish then asked ... . In: Klaus Haupt / Harald Wessel: Kisch was here. Reports on the "Rasenden Reporter" , Verlag der Nation , East Berlin 1985, pp. 221–236.

- Waltraud Kreidl: The whole life was beautiful [Interview with Max Bair] , in: Michael-Gaismair-Gesellschaft (Ed.): Gaismair Calendar 1993 , self-published, Innsbruck 1993, pp. 41–44.

- Günther Schwarberg : Three cows and one life . In: Zeitmagazin (Hamburg), September 2, 1994, pp. 10-14.

- Hans Landauer (with the collaboration of Erich Hackl ): Lexicon of Austrian fighters in Spain 1936–1939 . Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft , Vienna 2003. Complete, extended online version

- Klaus Haupt: The Tyrolean farmer's boy Max Bair and “The Three Cows” . In: Lisl Rizy / Willi Weinert (ed.): Was I a good soldier and comrade? Austrian Communists in the Spanish Civil War and after. A reader . Wiener Stern Verlag, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-9502478-0-0 , pp. 69-76.

- Friedrich Stepanek: "I fought all fascism". Life paths of Tyrolean Spanish fighters . Studienverlag , Innsbruck 2010, ISBN 978-3-7065-4833-5 .

- Egon Erwin Kisch: The three cows. A peasant story between Tyrol and Spain. With illustrations by Amado Oliver Mauprivez / ed. and commented by Joachim Gatterer. Edition Raetia , Bozen 2012, 173 pages, ISBN 978-88-7283-425-1 .

- Joachim Gatterer / Friedrich Stepanek: Internationalism and Region: About the Difficult Classification of Anti-Fascist Spain Fighters in Regional Memory Discourses Using the Example of Tyrol and South Tyrol , in: Geschichte und Region / Storia e regione , issue 1/2016 (25th year), p. 143– 158.

- Joachim Gatterer: Local history and world literature: Egon Erwin Kisch's report on the war in Spain “The three cows” , in: Georg Pichler / Heimo Halbrainer (ed.): Camaradas. Austrians in the Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, Clio Verlag, Graz 2017, pp. 197–207, ISBN 978-3-902542-56-4 .

Web links

- Biographical entry on Max Bair in the online lexicon of the Austrian fighters in Spain of the Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance (DÖW)

- Original sound from Max Bair (min: 31–35) in the radio feature by Renate Beckmann u. Klaus Ihlau (1998): Don Kischote or where fanatical curiosity leads - memories of the mad reporter , archive of the Austrian media library

Individual evidence

- ↑ The hamlet of Puig belongs administratively to the municipality of Steinach am Brenner . In contrast, Max Bair always named Matrei am Brenner as the reference community in his place of birth in self-written résumés , which can be traced back to the social and church ties of the hamlet of Puig to the community of Matrei. Cf. on this the printed documents in Joachim Gatterer (ed.): Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe. A farmer's story between Tyrol and Spain , Bozen 2012, pp. 133–140 and 156–160.

- ↑ See Egon Erwin Kisch: The three cows, Madrid 1938, pp. 10-12. Max Bair's curriculum vitae, printed in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012 (edited by Joachim Gatterer), p. 156.

- ↑ See Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012 (edited by Joachim Gatterer), pp. 12-13.

- ↑ ibid, note 2

- ↑ Cf. Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe, Madrid 1938, pp. 13–15 u. P. 22. Curriculum vitae of Max Bair, printed in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012 (edited by Joachim Gatterer), p. 156.

- ↑ Friedrich Stepanek: "I fought every fascism" , Innsbruck 2010, p. 186.

- ↑ See Egon Erwin Kisch: The three cows, Madrid 1938, pp. 21-23. Max Bair's curriculum vitae, printed in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012 (edited by Joachim Gatterer), p. 156.

- ↑ Max Bair quoted from Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012 (edited by Joachim Gatterer), p. 77. The complete interview by Waltraud Kreidl appeared in the Gaismair calendar 1993 , pp. 41–44.

- ↑ Cf. Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe, Madrid 1938, pp. 29–41.

- ↑ Egon Erwin Kisch: The three cows, Madrid 1938, pp. 42–44. Hans Landauer (Ed.): Lexicon of the Austrian Spanish Fighters 1936–1939 , p. 56.

- ↑ Klaus Haupt: The Tyrolean farmer's boy Max Bair and “The Three Cows” , in: Lisl Rizy / Willi Weinert (eds.): Have I been a good soldier and comrade ?, Vienna 2008, pp. 69–76.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 73–81.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 81–86.

- ^ See letter from Max Bair to Egon Erwin Kisch from October 1946, printed in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe, Bozen 2012, (edited by Joachim Gatterer), p. 146.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 98-104.

- ↑ Friedrich Stepanek: “I fought every fascism” , Innsbruck 2010, pp. 152–157.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 106–110. Max Bair's curriculum vitae, printed in: ibid., P. 157.

- ↑ See Günther Schwarberg: Drei Kühe und ein Leben , in: Zeitmagazin (Hamburg), September 2, 1994, pp. 10-14.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Afterword, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 113–114. Max Bair's curriculum vitae, printed in: ibid., P. 157.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Appendix, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 162–165.

- ↑ Joachim Gatterer: Appendix, in: Egon Erwin Kisch: Die drei Kühe , Bozen 2012, pp. 165–165.

- ↑ See book review by Erich Hackl : Write that down, Kisch! , in: Die Presse (April 19, 2013)

- ↑ With three cows in the Spanish Civil War , in: mein district.at (January 29, 2016)

- ↑ Markus Schramek: The Man with Two Names , in: Tiroler Tageszeitung (online) (February 7, 2016)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bair, Max |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hunter, Martin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian communist, volunteer in the Spanish civil war and resistance fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 28, 1917 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Matrei am Brenner , Tyrol |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 25, 2000 |

| Place of death | Berlin |