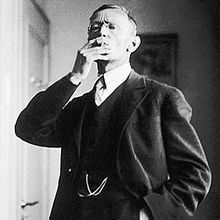

Peter Weiss

Peter Ulrich Weiss (pseudonym: Sinclair ; born November 8, 1916 in Nowawes near Potsdam ; † May 10, 1982 in Stockholm ) was a German-Swedish writer , painter , graphic artist and experimental filmmaker .

Peter Weiss made a name for himself in German post-war literature as a representative of avant-garde , meticulous descriptive literature, as an author of autobiographical prose and as a politically committed playwright. He achieved international success with the play Marat / Sade , which won the US theater and musical prize "Tony Award". That the documentary theater imputed "Auschwitz oratorio" The investigation led the mid-1960s to wide past political conflicts (the so-called. Vergangenheitsbewältigung ). Weiss' main text is the three-volume novelThe Aesthetics of Resistance , one of the "most weighty German-language works of the 70s and 80s". Weiss' early, surrealist- inspired work as a painter and experimental film director isless well known.

Life

Childhood and youth near Berlin and Bremen

Peter Weiss was born on November 8, 1916 in Nowawes near Potsdam as the eldest son of the Swiss actress Frieda Weiss (née Hummel, 1885–1958) and the Czech citizen Eugen “Jenö” Weiss (1885–1959). Peter Weiss had two half-brothers, Arwed (1905–1991) and Hans (1907–1977), from his mother's first marriage to the government architect Ernst Thierbach in Düsseldorf and Bochum, who was twenty years his senior. After the divorce, Frieda Weiss initially appeared alongside Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau “in leading roles on Reinhardt's stage” between 1913 and 1915 , including as the mother in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's Emilia Galotti at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin . Frieda Weiss broke off her theater career in 1915 in favor of starting a new family. She married the Hungarian Draper Jeno Weiss, who at that time as a lieutenant of the Austro-Hungarian army in the Galician Przemyśl was stationed. After Peter the siblings Irene (1920–2001), Margit Beatrice (1922–1934) and Gerhard Alexander (1924–1987) were born.

After Jenö Weiss was released from military service, the family moved to Bremen in 1918 and lived in Neustädter Grünenstrasse from 1921 to 1923. Jenö founded a successful textile goods business (Hoppe, Weiss & Co.), which helped the family achieve a high standard of living in the early twenties. At times the Weiss family employed a cook, a housekeeper and a nanny in the household. In 1920 Jenö Weiss converted to Christianity; henceforth the family no longer spoke about the father's Jewish descent - until 1938. In 1928 Peter Weiss was sent to Tübingen for just under five months. In 1929 the family returned to Berlin after moving several times within Bremen. Peter Weiss attended the Heinrich-von-Kleist-Gymnasium in Schmargendorf , which was characterized by a comparatively liberal atmosphere. At the beginning of the thirties Weiss developed an increased interest in art and culture: “In these years, between 1931 and 1933, I acquired all of my literary knowledge, all of Hesse , all of Thomas Mann , all of Brecht , we read everything as a whole young people. ”Under the guidance of Eugen Spiro , a member of the Berlin Secession , he began to paint at a drawing school. His role models were the German expressionists Emil Nolde , Paul Klee and Lyonel Feininger .

Jenö Weiss tried to assimilate during this time and applied for German citizenship . Jenö Weiss was “fascinated by Hitler and his pompous contempt for communism.” So it is not surprising that Peter Weiss learned not from his parents, but rather casually from one of his half-brothers, that his father was a Jew who had converted to the Protestant faith. In view of the uncertain future of the Weiss family in Germany, the father arranged for his son to move from high school to Rackow business school . There Weiss learned "typewriter and shorthand".

Stations of emigration

The years immediately following abroad, owing to the father's secret Jewish origins, initially had the character of apprenticeship and traveling years for Peter Weiss. From early 1935 to late 1936, Weiss' family lived in Chislehurst in south east London. Shortly before leaving, Peter's younger sister Margit Beatrice died at the age of twelve as a result of a car accident, an event that permanently unbalanced the family structure. Weiss experienced the death of his sister as "the beginning of the breakup of our family". Weiss attended the Polytechnic School of Photography in London in order to be able to “at least learn photography” contrary to the parents' expectations of the son's professional career. Weiss painted, among other things, The machines attack people and wrote the confession of a great painter. A little later he improvised his first exhibition "in a room above a garage in a hidden back alley" in London (Little Kinnerton Street). In 1936 the family moved to the north Bohemian town of Warnsdorf after business disagreements . Like his father and his siblings, Peter had Czechoslovak citizenship. “This is where writing began again and was done at the same time as painting. My first manuscripts were written and drawn back then. "

In connection with his Skruwe manuscript, Weiss made contact with Hermann Hesse in January 1937 . For him, Hesse's works were mirrors, “in which a longing identification is banned”. Weiss was encouraged in his artistic ambitions by Hesse and visited the later Nobel Prize winner for the first time in Montagnola in Ticino in the summer of the same year . Numerous Weiss texts from this period draw on Hesse's poetry and imagery. Hesse's encouragement strengthened Weiss in his decision to study at the Prague Art Academy , which Weiss took up in autumn 1937 with the painter Willi Nowak. In 1938 he was awarded the Academy Prize for his paintings The Great World Theater and The Garden Concert .

After Nazi Germany had annexed the Sudetenland as a result of the Munich Agreement in October 1938 , it was impossible for Peter Weiss to return to Warnsdorf. With the support of the sons from Frieda Weiss 'first marriage, who had stayed behind in Germany, Weiss' parents successfully moved to Borås , then to Alingsås in southern Sweden. Eugen Weiss became managing director of a new textile factory (SILFA) in Alingsås. Peter Weiss himself first went to Switzerland, but from February 1939 onwards, faced with unfamiliar language problems in Sweden, he experienced the emigration problem in all sharpness as a 22-year-old. The parents tried to uphold the “life lie” that they had left Germany for economic and not political reasons. Peter earned his living (200 crowns ) among other things as a textile pattern draftsman in his father's factory and at private painting schools.

Early prose works and films in Sweden

Peter Weiss moved to Stockholm at the end of 1940, where he lived mostly until his death. Apart from the journalist Max Barth , the sculptor Karl Helbig and the social medicine specialist Max Hodann , Weiss had hardly any contact with other emigrants and remained “on the verge of political emigration, which he regretted several times when he made himself their epic chronicler . “Weiss devoted himself above all to his artistic work. The paintings Fair on the Outskirts, Circus and Villa mia were created. In March 1941, the first official exhibition of Weiss' works followed in the Stockholm Mässhallen. The young painter complained to friends about a bitter failure in the face of “chauvinistic, idiotic reviews”; he got into his first creative crisis. During this time of crisis, Weiss also had his first psychoanalysis with Iwan Bratt in Alingsås in the summer of 1941, which lasted only a few weeks . In the same year he traveled to Italy. As a foreigner, Weiss was repeatedly dependent on odd jobs, including as a harvest worker. In 1942 he began studying at the Stockholm Art Academy and in 1943 he married the Swedish painter and sculptor Helga Henschen (1917–2002). In 1944 the daughter Randi-Maria (called Rebecca) was born. Weiss found acceptance into the Swedish art world, which was concerned with distinction and isolation. In 1944 he took part in the exhibition "Konstnärer i landsflykt" ("Artists in Exile") in Stockholm and Gothenburg . In 1946 Weiss lived for a time with the Danish artist and writer Le Klint . On November 8th of the same year he received the Swedish citizenship.

In 1947 Weiss published with the renowned Stockholm publisher Albert Bonnier under the title Från ö till ö ( From island to island , or: From Z to Z ; Ö is the last letter of the Swedish alphabet), a volume with thirty prose poems influenced by Stig Dagerman . As a correspondent for Stockholms-Tidningen , Weiss wrote seven reports from destroyed Berlin. The proximity to the German rubble literature of those years suggested a genuinely literary adaptation of the reports that Weiss presented in the form of the prose text De besegrade (Die Besiegten) . After his marriage to Helga Henschen was divorced in 1947, Weiss married “pro forma” the Spanish diplomat's daughter Carlota Dethorey (born 1928), because their son Paul was born in 1949 ”. The one-act Rotundan (The Tower) was created.

From 1952 Weiss worked as a lecturer at the Stockholm “Högskola” (today: Stockholm University) and taught film theory and practice as well as the theory of the Bauhaus . The experimental films Study I, II, III, IV and V were made. Weiss summarized his theoretical film considerations in the book Avantgardefilm (1956). By 1961 he had made a total of 16 documentaries in which he sought to combine social engagement and avant-garde art practice. Weiss used documentary recordings from everyday life in short films such as Ansikten i skugga (German: faces in the shadow ) about the life of destitute people in Stockholm and Enligt lag (German: in the name of the law ) about the living conditions in a youth prison in Uppsala . In 1959 he shot the feature film Hägringen / Fata Morgana based on the book Der Vogelfrei, his most important cinematic work. In the following year he wrote the screenplay for the commercial feature film Swedish Girls in Paris together with Barbro Boman (German distribution title: Temptation ), in which Weiss was involved as a picture director.

At this point in time - Weiss 'artistic activity in Sweden was largely unsuccessful - Suhrkamp Verlag , through Walter Höllerer's agency, accepted Weiss' "micro-novel" The shadow of the coachman's body, which was written in 1952 . The text was printed in an edition of 1000 copies in 1960 and illustrated by the author with his own collages . Weiss' narrative method of meticulously describing the narrator's surroundings found countless imitators and made Weiss an often imitated literary avant-garde (among other things, he inspired Ror Wolf to write the novel, Continuation of the Report in 1964 ).

1961 appeared as the second story Leavetaking , one after the death of parents (1958-59) dispute arising with one's own childhood and the history of the family until the beginning of the war. For the Swedish edition of Abschied (1962) a portfolio of nine collages was also created, which was later included in the new German edition. In 1962 Weiss published the novel Fluchtpunkt , for which he was awarded the Swiss Charles Veillon Prize . In connection with the two autobiographical works, Peter Weiss was the first participant in October 1962 at the meeting of Group 47 , the circle of important contemporary authors and literary critics who wanted to promote a renewal of German-language literature and the democratization of society after the end of the Nazi regime .

On January 4th, 1964, after living together for twelve years, Weiss married the Swedish set designer and sculptor Baroness Gunilla Palmstierna .

Literary success in Germany

On April 29, 1964, a Weiss drama entitled The Persecution and Murder of Jean Paul Marat was premiered by the acting group of the Charenton Hospice under the guidance of Mr de Sade . Polish director Konrad Swinarski directed it at the Berlin Schillertheater . The piece thrived on the "conflict between the extreme individualism and the thought of a political and social upheaval." This conflict manifests itself in the fictional confrontation of the revolutionary Jean Paul Marat with the connoisseur de Sade on the subject of violence in the form of a playful recapitulation of the assassination of Marat, a decade and a half ago, during the Napoleonic Restoration of 1808. Marat / Sade - the short title of the play - was successful worldwide and won the US theater and musical award in 1966 for the “best play " excellent.

The next play by Weiss, The Investigation (subtitle: "Oratorio in eleven songs"), dealt with the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt am Main. Peter Palitzsch promised a world premiere for the Stuttgart State Theater. In view of the extraordinary importance of the subject, the director of the Freie Volksbühne Berlin and Nestor of the political theater, Erwin Piscator , suggested an open world premiere to the Suhrkamp-Theaterverlag in May 1965. The simultaneous premiere of the play was agreed for October 19, 1965, the 75th anniversary of the first performance at the Volksbühne in Berlin . 14 theaters in both parts of Germany and the Royal Shakespeare Company in London took part in the premiere of the Ring. As with the productions of the Marat / Sade , cinematic recordings were made from the investigation .

In 1967 Weiss brought his political musical Gesang vom Lusitanischen Popanz , which dealt critically with the Portuguese colonial rule, on stage and took part in the Russell Tribunal against the Vietnam War in Stockholm and Roskilde. One of the so-called 'judges' of the Russell Tribunal was the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre . Further premieres followed: as Drama designated scenic collage Viet Nam Discourse in Frankfurt (1968) and the analytical drama Trotsky in exile in Dusseldorf (1970), which, given his criticism of the authoritarian Stalinism and update, dissidents ' -Thematik in in both parts of Germany. The first health problems manifested themselves in a heart attack that Peter Weiss suffered on June 8, 1970 at the age of 53. His scenic biography Hölderlin was premiered in Stuttgart in 1971. Weiss' third child Nadja was born in 1972. The author traveled to Moscow for the Soviet Writers' Congress in 1974 and to Volgograd. At the suggestion of the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman , Weiss wrote a stage version of Franz Kafka's unfinished novel The Trial that same year , which was based closely on the original and premiered in Bremen the following year.

The late work of memory politics

In 1975, the first volume of Peter Weiss' main work, The Aesthetics of Resistance , on which Weiss had been working since 1972, was published. The novel project represented the attempt to process and convey the historical and social experiences and the aesthetic and political insights of the workers' movement during the years of resistance against fascism. Weiss, who was previously celebrated as the author of Marat / Sade , initially experienced multiple rejection by the West German feuilletons . He “sacrificed his aesthetic standards and thus his identity as an artist in favor of political partisanship; in “loyalty to the Nibelungs ” to the Soviet Union, he hushed up the internal contradictions of the left; After all, he had no individual character drawing, no living plot - in short: no novel-like design. ”When volumes two and three of Aesthetics were published in 1978 and 1981 , the broader discussion that had now started led to a noticeable change in assessment and to mostly positive ones Meetings.

Shortly before his death, Peter Weiss and Wolfgang Fritz Haug , the publisher of the magazine “ Das Argument ”, agreed on a collaboration. By then, “Das Argument” had already collaborated with numerous writers such as Christa Wolf , Erich Fried , Wolf Biermann , Volker Braun and Elfriede Jelinek . In 1981 Weiss' diary-like notebooks were published 1971–1980 , which, among other things, illustrated the work process on the aesthetics of resistance , followed a little later by the notebooks 1960–1971 (posthumously). Weiss was honored with the literary prizes of the cities of Cologne and Bremen. In 1982 the play Der neue Prozess nach Franz Kafka was premiered in Stockholm under the direction of the author.

On May 2, 1982 Weiss turned down the honorary doctorates he had been offered by the Wilhelm Pieck University of Rostock and the Philipps University of Marburg . Shortly after the premiere of The New Trial , Peter Weiss died of a heart attack on May 10, 1982 after a decade of exhausting work on the aesthetics of resistance in a Stockholm clinic. Only a few days before his death he had learned of the intention of the German Academy for Language and Poetry to honor him with the Georg Büchner Prize , the most important literary prize in the German-speaking area. The already agreed collaboration with “Das Argument” did not materialize. The Berlin “ Volksuni ”, co-initiated by Wolfgang Fritz Haug, dedicated its closing event to Peter Weiss under the impression of the news of his death and subsequently did its best to spread the aesthetics of resistance with anthologies and conferences .

The Foundation Archive of the Academy of Arts (Peter Weiss Archive) has been keeping Peter Weiss' estate since 1986 .

Artistic work and effect

Romanticizing beginnings

After the death of his sister Margit in 1934, Weiss wrote the first self-understanding texts that were not published. In these early neo-romantic texts, Weiss “first had to laboriously work through epigonal imprints to his own language”. The first prose texts published in Swedish since the late 1940s are influenced by avant-garde authors of Swedish modernism. These texts, shaped by an existentialist attitude towards life and written in Swedish, gave expression to experiences of homelessness and principled forlornness: Från ö till ö ("From island to island"), De besegrade ("The vanquished"), Document I , "The Paris Manuscript" .

The "micro-novel" The Shadow of the Coachman's Body , created in 1952, is of particular importance , in which Weiss descriptively dismantled everyday processes and found a language of description that was freed from subjective feelings. In its consistent differentiation from traditional narrative methods , the Kutscher text correlated with the descriptive literature of those years when it was published in 1960. It fell "now as avant-garde prose belatedly into the reception of the nouveau roman ."

After the death of the parents, autobiographical, psychoanalytically trained prose texts came to the fore ( Copenhagen Journal , Farewell to Parents , Vanishing Point ), which alienated some critics, especially in their comparatively conventional narrative pattern. In these texts, Weiss sought to ascertain his childhood and adolescent experiences and to fathom his socialization history against the background of an unbridgeable distance to his parents.

Peter Weiss achieved a breakthrough in 1964 with the Marat / Sade piece. The disputing drama confronted the mercilessly individualistic attitude of the Marquis de Sade with the revolutionary fanaticism of Jean Paul Marat and his partisan Jacques Roux . In the play, the two ideological opponents get excited about the sense and nonsense of revolutions and violence as well as about the question of a just economic and value system. In alternation, the choir , which de Sade recruits from prison inmates, presents the concerns of the poor city population to the national convention - and therefore to the audience in the theater. By tearing down the “ fourth wall ” with the third stand , the “piece in a piece” unfolds its delimiting character. The director of the Schillertheater Berlin , Boleslaw Barlog , initially received the work with great skepticism. However, the Polish director Konrad Swinarski commissioned by him , who had not long since arrived in the West, laid the foundation for the play's global success with its premiere on April 29, 1964 in West Berlin . After the premiere of the Marat / Sade , the “ Spiegel ” reported appreciatively: “People loved, prayed, blessed, sang, danced, bathed, showered, argued, tortured, whipped, murdered, beheaded, acrobats appeared on stage, mimes entered Jugglers, nuns, a band sat on the stage and did not give way. "

Configurations of the Political

Weiss made several theoretical comments on his theater work and described in the programmatic texts Das Material und die Modelle (1968) and Link All Cells of Resistance Together (1973) a dramaturgy of as direct an effectiveness as possible, which should turn the stage into an instrument for forming political opinion. The claim “that art must have the power to change life” he tried to redeem in 1965 in the work The Investigation, known as the “Auschwitz Oratorio” , which marked the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial from 1963 to 1965 using documentary means Theater thematized. In eleven chants, Weiss lets the witnesses (i.e. the victims) appear anonymously, whereas the accused and former SS overseers appear under their real names. The author compares the statements of perpetrators, witnesses and judges with each other in such a way that the contradictions in the statements of the perpetrators are uncovered. At the same time, the witnesses inform the audience about the atrocities in the concentration and extermination camps. The extremely objective text on the stage provoked anonymous insulting and threatening letters against the author and the directors of the world premiere productions. Although numerous stages except West Berlin, Essen, Cologne, Munich and Rostock only left The Investigation 1965/66 on the program for a short time, the memorial text has since then asserted itself as a consistent piece of literature about the Holocaust on German stages.

The in-depth examination of the repression practice of German post-war society in the investigation was accompanied by a process of politicization on the part of the author. In his programmatic 10 Working Points of an Author in the Divided World in 1965 Weiss took a position for the socialist side in the antagonistic East-West conflict and scolded German writers for a lack of commitment in the fight against the will to forget, militarism and nationalism. The stage texts that followed from 1967 on, in keeping with the 10 working points, testified to a political and moral stance for the rebellious oppressed in history.

The politically accentuated dramaturgy that Weiss pursued in the late 1960s used topoi such as Angola as an example of business in the name of the West (song from the Lusitan bogey) and Vietnam to illustrate a "history of seizures of power, colonizations and liberations" (Viet Nam Discourse) . Although Botho Strauss rated Weiss' Vietnam play in 1968 as one of “the most spectacular theater events of the season”, Weiss had to admit shortly afterwards that “the path that led him to the 'Vietnam Discourse' was necessary, but now can no longer be taken. "

Turning away from the dramaturgy of the documentary pieces, whose initially soberly ascertaining style had given way to an increasingly agitative handwriting, Weiss returned to a drama structure that again placed the focus on classical protagonists . Using the two intellectual figures Leon Trotsky and Friedrich Hölderlin , Weiss worked on an unresolved revolutionary past (Trotsky in exile) in confrontation with the official historical image of the Soviet Union and reflected on the fundamental problems of the revolution (Holderlin) . A repetition of the extraordinary successes of the mid-1960s did not succeed with these pieces. In his last dramatic works, Weiss transferred the hermetic world of Franz Kafka's novel fragment The Process into the presence of multinational corporations and political power and surveillance apparatuses ( The Process , The New Process ).

The aesthetics of resistance

The three-volume work The Aesthetics of Resistance , which was published between 1975 and 1981, reflects the debates and conflicts within the communist and anti-fascist movement during the time of National Socialist rule. Superficially, the novel tells the story of a working-class son who was born in 1917 in Nazi Germany and when he emigrated. This fictional first-person narrator is developing into an author and chronicler of the anti-fascist struggle. It embodies the political as well as the artistic responsibility towards a historical-philosophical mandate: "the comprehensive self-liberation of the oppressed". A key concern of the trilogy, which was set between 1937 and 1945, is the reflection of the relationship between art and politics. Using works of the fine arts and literature , Weiss develops models for appropriating the proletarian struggle against oppression. In the process, the conversational novel always pursues, in the sense of critical self-assurance, the examination of the contradictions and errors of left politics as well as the historical failure of the labor movement .

While the institutionalized cultural scene was only gradually appreciating the importance of the trilogy, The Aesthetics of Resistance among Leftists in West and East Germany soon became popular. In German-speaking countries, the work developed into a focal point for political-aesthetic reading courses and discussion events. A kind of initial spark for this form of reception was the Berlin “ Volksuni ” in 1981. Several reading groups have already come together there, partly from students and lecturers, partly from non-university, especially left-wing trade union circles. The attraction of Weiss' three-volume major work was due to the fact that the author told recent German history from the perspective of the resistance against National Socialism . The monumental novel about the fascist era in Europe provided an opportunity for identification that was widely accepted in the context of the debate about coming to terms with the past . In the GDR , all three volumes of Aesthetics of Resistance were published in 1983 in a first edition limited to 5000 copies by Henschel Verlag . As a result, the work was only available with difficulty until a second edition in 1987. In view of the extraordinarily broad reception of the trilogy, Gerhard Scheit described The Aesthetics of Resistance as the “last common denominator” of the German left.

Fine arts and experimental film

Weiss' painting and his graphic works are characterized by a rather gloomy, “ old master ” orientation. They are characterized by a representational style of painting that transitions into the allegorical , which is just as influenced by Expressionism as by the old masters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel . “In terms of composition, self-portrait and self-interpretation are combined with a view of a totality that directly addresses a painting from 1937 in the title: The Great World Theater (it has been owned by the Moderna Muséet in Stockholm since 1968 ). The problems of artistic existence - and their contrast to the bourgeois world threatened by catastrophes - become thematic here very early and in a certain sense remain so in the overall works of the poet and painter. "

A first exhibition in May 1941 in Stockholm's port and office district Norrmalm (Brunkebergstorg) was not very well received from Weiss' perspective. Three years later, however, Weiss' paintings were recognized at the joint exhibition “Konstnärer i landsflykt” (“Artists in Exile”). In the following works, Weiss sought the connection to artistic modernism . Weiss combined documentary and visionary elements in visual collages and illustrations for his prose books.

In view of the overly static limits of the visual arts, Weiss turned to film aesthetic experiments between 1952 and 1961. He explicitly described his cinematographic ambitions with the term avant-garde film (the title of a programmatic publication from 1956). Six surrealist and five documentary short films were made. The latter dealt with outsider groups of the Scandinavian welfare society , but in the case of Enligt lag (in the name of the law ) in 1957 led to a conflict with the state film censorship due to 'pornographic' freedom of movement . In addition, Weiss shot the 80-minute feature film Hägringen in 1958/59 , an adaptation of his early prose work Der Verschollene / Document I, about the encounter of a strange youth with the big city.

An unsuccessful commercial production followed in 1960 with the feature film Svenska flickor i Paris (Swedish Girls in Paris) . The work on this fictional film, which also reflected Tinguely's surrealist art , was overshadowed by a fundamental dissent between producer Lars Burman and director Weiss about the intended cinematic effect. Weiss subsequently distanced himself from this experiment in the commercial field. Since the 1980s, Weiss' cinematic works have also been presented to a German public at various film days (International Forum of Young Films, 1980; Nordic Film Days Lübeck , 1986, etc.).

Although Weiss was never able to make a living from his work as a visual artist and the filmic works, which were mainly created in Sweden, were denied sustained resonance in international competitions despite various awards, the Berlin Senate immediately before the Marat / Sade success gave him the function of Founding director of the film academy in West Berlin (dffb), which is currently being established. As the founding director Erwin Leiser , suggested by Peter Weiss, recalled that Weiss refused “because he shied away from the thought of administrative work and constant confrontation with German bureaucracy.” Weiss wanted to work “merely as an artistic advisor” for the film academy be.

Since the prose text duels in the early 1950s, the aesthetic qualities of film have shaped Weiss' prose texts significantly. Even decades after Weiss turned away from experimental film as an art form, the adoption of visual techniques from the field of film remained a constant in his literary work.

Weiss reception in transition

Weiss's artistic success is linked to his literary work. It was only later that the author was rediscovered as an artistic “border crosser”. While Weiss was originally perceived as the author of avant-garde prose and political plays, relevant exhibitions and performances of his experimental films since the 1980s have increasingly brought his work as a visual artist and filmmaker into the public eye. At the same time, there were “changes in the conditions for recording Weiss' work” and a differentiation of the interpretative approaches of his work. The more recent thematic approaches beyond the appreciation of the avant-garde and political author and the intermedia references of his texts include the examination of polyphonic claims to self-determination or intercultural perspectives within Weiss' work.

The history of the impact of Weiss's oeuvre includes several cultural initiatives that have dedicated themselves to the tradition of his concept of art. Since 1989, the " International Peter Weiss Society " has dedicated itself to the care and research of the literary, filmic and visual artistic work of Peter Weiss as well as to the support and promotion of cultural and political initiatives in the interests of the artist. The city of Bochum has been awarding theater and film directors, writers and visual artists with the " Peter Weiss Prize " since 1990 . This culture award, which is awarded every two years, is endowed with 15,000 euros. In 1993 a " Peter Weiss Foundation for Art and Politics " was established in Berlin . The aim of the foundation, which is the sponsor of the international literature festival berlin , is to promote art, culture and political and aesthetic education.

In addition, a comprehensive school in Unna (since 1991), a special library in Berlin (since 2002), a cultural center in Rostock (since 2009), a square and an alley in Berlin (since 1995/2007), a street in Bremer Neustadt ( since 2009) as well as one place each in Potsdam-Babelsberg (since 2010) and in Stockholm (since 2016) the name of the writer. A commemorative plaque has been on Weiss's birthplace in today's Rudolf-Breitscheid-Strasse 232 in Potsdam since 1996.

Awards

- 1938: Prize of the Prague Academy of Fine Arts for The Great World Theater and Garden Concert

- 1963: Charles Veillon Prize for Vanishing Point ( Lausanne )

- 1965: Lessing Prize of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg

- 1965: Literature Prize of the Swedish Workers' Education Movement (svenska arbetarrörelsens litteraturpris)

- 1966: Heinrich Mann Prize of the German Academy of the Arts , Berlin (GDR)

- 1966: New York Drama Critics' Circle Award (Best Play) for Marat / Sade

- 1966: Tony Award for Best Play for Marat / Sade

- 1967: Carl Albert Anderson Prize (Stockholm Culture Prize)

- 1978: Thomas Dehler Prize from the Federal Ministry for Internal German Relations

- 1981: Prize from the Südwestfunk literature magazine

- 1981: Literature Prize of the City of Cologne ( Heinrich Böll Prize )

- 1982: Literature Prize of the City of Bremen for The Aesthetics of Resistance (see photo at the beginning)

- 1982: De Nios Prize (“Small Nobel Prize”) awarded, but not presented

- 1982: Georg Büchner Prize for Weiss' wide-ranging work (posthumously on October 15, 1982)

- 1982: Swedish Theater Critic Award (svenska teaterkritikerpriset) (posthumous)

Work overview

Painting and graphics

Exhibition catalogs

- Peter Weiss. Måleri, collage, Teckning. 1933-1960. En utställning producerad av Södertälje Konsthall, Sverige. Editor: Per drug. Södertälje 1976 (Swedish and German).

- The painter Peter Weiss. Pictures, drawings, collages, films . Editing and design: Peter Spielmann. Berlin: Frölich and Kaufmann 1982 (for the exhibition in the Museum Bochum).

- Peter Weiss as a painter. Catalog for the exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bremen, January 16 to February 20, 1983 . Editor: Annette Meyer zu Eissen. Bremen 1983.

- Raimund Hoffmann: Peter Weiss. Painting, drawings, collages. Berlin: Henschelverlag Art and Society 1984.

- Peter Weiss. Life and work. An exhibition. Akademie der Künste, Berlin February 24 to April 28, 1991 . Edited by Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss and Jürgen Schutte. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991.

Illustrations of own and foreign prose

- 1938: Hermann Hesse : Childhood of the magician. An autobiographical fairy tale. Handwritten, illustrated and with a comment by Peter Weiss. Facsimile. Frankfurt am Main: Insel 1974 (Insel Taschenbuch 67).

- 1938 Hermann Hesse: The exiled husband or Anton Schievelbeyn's unwilling journey to East India. Handwritten and illustrated by Peter Weiss . Frankfurt am Main: Insel 1977 (Insel Taschenbuch 260). (26 drawings)

- 1947: Från ö till ö: teckningar av författaren. Stockholm: Bonnier (= from island to island . Berlin: Frölich & Kaufmann 1984). (4 illustrations)

- 1951: duels . Private print Stockholm 1953 (= Das Duell . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1972) (10 pen drawings).

- 1958: Nils Holmberg: Tusen och en natt. Första delen / Andra Samlingen. Stockholm: Tidens bokklubb. (Two-volume Swedish edition of Thousand and One Nights with 16 + 12 collages)

- 1960: The shadow of the coachman's body . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. (7 collages)

- 1963: Diagnos . Staffanstorp: Cavefors (= German new edition Farewell to Parents . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1980). (8 collages)

Films (selection)

In early experimental films, Peter Weiss was not only responsible for the script, direction and editing, but also played a role.

- 1952: Study I: Uppvaknandet (Svensk Experimentfilmstudio, bw, 6 min.)

- 1952: Study II: Hallucinationer (Svensk Experimentfilmstudio, bw, 6 min.)

- 1953: Study III (Svensk Experimentfilmstudio, bw, 6 min.)

- 1955: Study IV: Frigörelse (working groups for film, bw, 9 min.)

- 1955: Study V: Växelspel (working groups for film, bw, 9 min.)

- 1959: Hägringen / Fata Morgana (based on Weiss' story Document I / The Bird Free ) (Nordisk Tonefilm, sw, 81 min.)

- 1960/61: Svenska flickor i Paris / Paris Playgirl . (A Swede in Paris) (Wivefilm, sw, 77 min. Premiere Finland, June 15, 1962)

prose

- 1947: Från ö till ö. Bonnier , Stockholm (= from island to island . Berlin 1984).

- 1948: De besegrade. Bonnier, Stockholm (= The vanquished. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985).

- 1949: Document I. Stockholm: private printing (also as: Der Vogelfrei ) (= Sinclair: Der Fremde. Erzählung. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1980).

- 1953: duels . Stockholm: private printing (= Das Duell. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972).

- 1956: avant-garde film. Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm (Svensk Filmbibliotek 7) (= Avantgarde Film , extended German translation, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995 using a typescript and a partial translation in Akzente no. 2/1963).

- 1960: The shadow of the coachman's body . Micro-novel. Suhrkamp (= thousand printing 3), Frankfurt am Main.

- 1961: Farewell to my parents . Narrative. Suhrkamp. Frankfurt am Main.

- 1962: vanishing point . Novel. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main.

- 1963: The conversation of the three walkers. Fragment. Suhrkamp (= edition suhrkamp 3), Frankfurt am Main.

- 1968/71: Rapporte / Rapporte 2. Collected small works from magazines, Suhrkamp (= edition suhrkamp 276/444), Frankfurt am Main.

- 1975–1981: The Aesthetics of Resistance . Novel. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main (first volume: 1975. second volume: 1978. third volume: 1981) (= The Aesthetics of Resistance . Editing and direction: Karl Bruckmaier . Der Hörverlag , Munich 2007).

- 1981/82: Notebooks. 1971–1980 / notebooks. 1960-1971. Two volumes. Suhrkamp (= edition suhrkamp 1067/1135), Frankfurt am Main.

published posthumously

- 2000: the situation . Novel. Translated from the Swedish by Wiebke Ankersen. Suhrkamp (created: 1956), Frankfurt am Main.

- 2006: The Copenhagen Journal. Critical edition. Edited by Rainer Gerlach , Jürgen Schutte. Wallstein (created: 1960), Göttingen.

- 2008: We are ciphers for one another. The Paris manuscript by Peter Weiss. Edited by Axel Schmolke. Rotbuch 2008 (created: 1950), Berlin.

- 2011: The notebooks. Critical complete edition. Edited by Jürgen Schutte in collaboration with Wiebke Amthor and Jenny Willner. Second, verb. and additional edition. Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert [With the notebooks 1960–1971 and the notebooks 1971–1980 as well as the second edition with the directory of the working library by Peter Weiss and Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss]

Plays

- 1948: Rotundan (German: The Tower ). World premiere: Study-Scenen, Stockholm, September 28, 1950 (director: Sten Larsson). First broadcast of the radio play version: Hessischer Rundfunk , April 16, 1962. German-language premiere: Theater am Belvedere, Vienna, December 2, 1967 (director: Irimbert Ganser)

- 1952: Försäkringen (German: The Insurance ). World premiere: University of Gothenburg, winter 1966. German-language premiere: Städtische Bühnen Essen, April 8, 1971 (director: Hans Neuenfels )

- 1963: night with guests . World premiere: Schillertheater Berlin, November 16, 1963 (Director: Deryk Mendel)

- 1962–65: The persecution and murder of Jean Paul Marat portrayed by the acting group of the Charenton Hospice under the guidance of Mr. de Sade . World premiere: Schillertheater Berlin, April 29, 1964 (Director: Konrad Swinarski )

- 1963–68: How Mockinpott's suffering is cast out . World premiere: Landestheater, Studio im Künstlerhaus , Hanover, May 16, 1968 (Director: Horst Zankl )

- 1964: Inferno (first published in 2003). World premiere: Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe , January 16, 2008 (Director: Thomas Krupa)

- 1965: The investigation . Open world premiere on October 19, 1965 on 14 German theaters and the Royal Shakespeare Company , London

- 1965–67: Singing from the Lusitan popanz . World premiere: Scala Teatern, Stockholm, January 26, 1967 (directed by Etienne Glaser with theater collective). German-language premiere: Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer , Berlin, October 6, 1967 (Director: Karl Paryla )

- 1966–68: Discourse on the prehistory and course of the long war of liberation in Vietnam as an example of the necessity of the armed struggle of the oppressed against their oppressors as well as the attempts of the United States of America to destroy the foundations of the revolution . World premiere: Städtische Bühnen Frankfurt , March 20, 1968 (director: Harry Buckwitz ) as a Viet Nam discourse

- 1968–69: Trotsky in exile . World premiere: Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus , January 20, 1970 (Director: Harry Buckwitz)

- 1970–72: Holderlin . World premiere: Württembergisches Staatstheater Stuttgart , September 18, 1971 (Director: Peter Palitzsch )

- 1974–76: The Trial . World premiere: Theater of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen , May 28, 1975 (Director: Helm Bindseil) and United City Theaters of Krefeld and Mönchengladbach (Director: Joachim Fontheim)

- 1981–82: The new process . World premiere: Dramaten , Stockholm, March 12, 1982 (directors: Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss and Peter Weiss). German-language premiere: Freie Volksbühne, Berlin, March 25, 1983 (director: Roberto Ciulli )

Work and collective editions

A complete edition of the works of Peter Weiss is not available.

- 1976/77: Peter Weiss. Pieces I / Pieces II . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 1977: Peter Weiss. Pieces . Ed. And with an afterword by Manfred Haiduk . Berlin: Henschel.

- 1986: Peter Weiss. Think in terms of opposites. A reader . Selected by Rainer Gerlach and Matthias Richter. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 1986: Interview with Peter Weiss . Edited by Rainer Gerlach and Matthias Richter. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 1991: Peter Weiss: Works in six volumes . Edited by Suhrkamp Verlag in collaboration with Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 2016: On the trail of the unattainable. Essays and essays . Berlin: Verbrecher Verlag (brings together for the first time the articles and essays by Weiss that have been published in Swedish in German translation)

Letter issues

- 1992: Peter Weiss. Letters to Hermann Lewin Goldschmidt and Robert Jungk 1938–1980 . Leipzig: Reclam.

- 2007: Siegfried Unseld , Peter Weiss: The exchange of letters . Edited by Rainer Gerlach. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 2009: Hermann Hesse, Peter Weiss. “Dear great magician” - Correspondence 1937–1962 . Edited by Beat Mazenauer and Volker Michels . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- 2010: This side and beyond the border. Peter Weiss - Manfred Haiduk. The correspondence 1965–1982 . Edited by Rainer Gerlach and Jürgen Schutte. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag, ISBN 978-3-86110-478-0 .

- 2011: Peter Weiss: Letters to Henriette Itta Blumenthal. Edited by Angela Abmeier and Hannes Bajohr. Berlin: Matthes and Seitz. ISBN 978-3-88221-698-1 .

Reception in film, radio, music and the visual arts

Feature films

- Farewell to my parents . Director: Astrid Johanna Ofner. Vienna: AFC - Austrian Films, 2017 (80-minute film based on Weiss' autobiographical story of the same name)

Film documentaries

- To view: Peter Weiss . Director: Harun Farocki . Berlin: Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, 1979 (44-minute presentation of the work on the aesthetics of resistance ).

- Short films by Peter Weiss . Director: Harun Farocki. Berlin: Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, 1982 (44- or 80-minute introduction to Weiss' cinematic work on behalf of WDR )

- Vanishing point painting. The painter Peter Weiss . Director: Norbert Bunge , Christine Fischer-Defoy . Berlin: Norbert Bunge Filmproduktion, 1986 (44-minute television film about Weiss and his painting, made in cooperation with WDR).

- Strange walks in and through and out / ingenting . Director: Staffan Lamm. Copenhagen: Film og Lyd Production, 1986 (50-minute portrait of Weiss' cinematic work).

- The Unrelated: Peter Weiss - Life in Contrasts . Director: Ullrich Kasten. Berlin, Potsdam etc .: RBB , SWR , DRS , ARTE , 2003 (88-minute literary film essay ; Special Prize for Culture from the State of North Rhine-Westphalia at the Adolf Grimme Prize 2004 for Ullrich Kasten and Jens-Fietje Dwars ).

There are also several television productions of Weiss' texts.

Radio features via Peter Weiss

- “Brecht shook my hand briefly” - Peter Weiss and the battle signals of intelligence . Script and direction: Katharina Teichgräber, production: Bayerischer Rundfunk , 2007, 46 min.

- Peter Weiss, all German - an original sound chronicle . Director: Thomas Kretschmer, Production: Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2007, approx. 60 min.

- My life is a dichotomy: the hug and repudiation of Peter Weiss . A feature by Lutz Volke about the strange handling of a socialist author in a socialist state. Production: Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk , 2010, approx. 60 min.

- Life - a dichotomy. A long night over Peter Weiss . Script and direction: Lutz Volke , production: Deutschlandfunk , November 6, 2010, approx. 160 min.

- Peter Weiss on his 100th birthday. “I was a stranger wherever I went.” Script and direction: Matthias Kußmann , production: SWR , November 8, 2016, 54:40 min.

About a dozen radio play productions based on the works of Peter Weiss and several production recordings on LP and CD audio books are not listed.

Scoring of the literary and cinematic work (without stage music, selection)

- Luigi Nono : Ricorda cosa ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz . World premiere: March 17, 1967 (composition based on the incidental music for The Investigation , premiered on October 19, 1965 in Essen, Potsdam, Rostock and West Berlin). Stage or radio play music for the investigation is also available from Paul Dessau and Siegfried Matthus .

- Peter Michael Hamel : Kafka-Weiss dialogues for viola and violoncello (based on incidental music for The New Trial ), world premiere: Munich 1984, duration: 25 min.

- Walter Haupt: Marat . World premiere: Staatstheater Kassel, June 23, 1984

- Reinhard Febel : Night with guests . For two sopranos, alto, tenor, baritone, bass and orchestra. World premiere: Kiel Opera , May 15, 1988, duration: 75 min.

- Frederic Rzewski : The Triumph of Death . Composition for voices and string quartet (1987/88), based on The Investigation . World premiere: Yale University , around 1991, German premiere: Kunstfest Weimar , August 30, 2015

- Detlef Heusinger: The tower. Music theater in four scenes (1986/87). World premiere: Theater Bremen and Radio Bremen , January 24, 1989

- Gerhard Stäbler : Jerk-shift (o) ben Zuck-. Orchestral pieces (one wedged into the other) with an obbligato accordion (based on motifs from Frigörelse ). World premiere: Essen, 1989

- Kalevi Aho : Pergamon. Cantata for 4 orchestral groups, 4 reciters and organ . World premiere: Helsinki, September 1, 1990 (commissioned work for the University of Helsinki for the 350th anniversary of the university); the text comes mainly from the beginning of The Aesthetics of Resistance and uses two more sentences ("We look back to a prehistoric time ..." or "You, the subject ...") before the end of the first paragraph. The four reciters read the three text excerpts simultaneously in four languages: German, Finnish, Swedish and ancient Greek.

- Jan Müller-Wieland : The insurance . World premiere: Staatstheater Darmstadt , February 27, 1999

- Johannes Kalitzke : Inferno: Opera . World premiere: Theater am Goetheplatz , Bremen, June 11, 2005

- Nikolaus Brass : Fallacies of Hope - German Requiem (2006). Music for 32 voices in 4 groups with text projection (ad libitum) from The Aesthetics of Resistance , duration: 24 min.

- Helmut Oehring : Quixote or The Porcelain Lance (based on the aesthetics of resistance ). World premiere: Festspielhaus Hellerau , November 27, 2008

- Claude Lenners : The Tower (Libretto: Waut Koeken). World premiere: Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg , October 6, 2011

- Friedrich Schenker : Aesthetics of Resistance I for bass clarinet and ensemble. World premiere: Gewandhaus (Leipzig) , commissioned work, January 16, 2013

- Stefan Litwin : Night with guests - a morality in one act as musical theater. World premiere: Saar University of Music , Saarbrücken, commissioned work, October 21, 2016

Reception in the fine arts

- Fritz Cremer : over 100 drawings and prints on The Aesthetics of Resistance (1983 to 1985).

- Hubertus Giebe : The Resistance - for Peter Weiss I – III (1984 / 85–1986 / 87). New National Gallery, Berlin.

- Rainer Wölzl: Pergamon. To Peter Weiss' “The Aesthetics of Resistance” . Vienna: Picus 2002.

Literary society

The International Peter Weiss Society (IPWG) is a literary society that will take place on 22./23. April 1989 in Karlsruhe and serves the maintenance and research of the literary, cinematic and visual artistic work of Peter Weiss. The statutory seat of the company is Berlin . Since 1989 the society has published the “Notblätter” twice a year and since 1992 the “Peter Weiss Yearbook” once a year.

literature

bibliography

- Peer-Ingo Litschke: Peter Weiss Bibliography (PWB). International catalog of primary and secondary literature, including the visual arts and films, taking into account early artistic attempts. Verlag Mainz, Aachen 2000, ISBN 3-89653-774-1 .

Biographies and general presentations

- Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss. Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-017633-6 (work biography).

- Volker Canaris (Ed.): About Peter Weiss. 5th edition, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 1981, ISBN 3-518-10408-X , 1970 (edition suhrkamp; 408).

- Robert Cohen : Peter Weiss in his time. Life and work. Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 1992, ISBN 3-47-600838-X .

- Jens-Fietje Dwars : And yet hope. Peter Weiss. A biography. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-351-02637-0 .

- Anne E. Dünzelmann : Peter Weiss - Bremer localizations . Bibliography. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-7412-9367-2 .

- Henning Falkenstein: Peter Weiss. Volume 125 of the series Heads of the 20th Century . Morgenbuch Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-371-00392-2 .

- Rainer Gerlach (Ed.): Peter Weiss. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1984, ISBN 3-518-38536-4 (Suhrkamp materials; 2036).

- Birgit Lahann : Peter Weiss. The homeless world citizen . JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 2016, ISBN 978-3-8012-0490-7 .

- Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss, Jürgen Schutte (Ed.): Peter Weiss. Life and work. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1991, ISBN 3-518-04412-5 (book accompanying the exhibition of the same name).

- Werner Schmidt: Peter Weiss. Biography . Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-42570-1 .

- Jochen Vogt : Peter Weiss. With testimonials and photo documents. 3rd edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-50367-0 (rowohlt's monographs, 50376).

- Rudolf Wolff (Ed.): Peter Weiss. Work and effect. Bouvier, Bonn 1987, ISBN 3-416-01837-0 (Profile Collection; Vol. 27).

Individual aspects

- Margrid Bircken, Dieter Mersch , Hans-Christian Stillmark (eds.): A crack runs through the author - transmedial productions in the work of Peter Weiss. Transcript, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-8376-1156-4 (series: Metabasis).

- Jennifer Clare: Protexts. Interactions between literary writing processes and political opposition around 1968 . transcript, Bielefeld 2016.

- Robert Cohen : Bio-bibliographical handbook on Peter Weiss' “Aesthetics of Resistance”. Argument Verlag, Berlin 1989.

- Rainer Gerlach: The importance of the Suhrkamp publishing house for the work of Peter Weiss. Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2005, ISBN 3-86110-375-3 (plus dissertation, FU Berlin 2004).

- Nils Göbel: “We cannot invent a form that does not exist in us”. Genre issues, intertextuality and language criticism in 'Farewell to Parents' and 'Vanishing Point' by Peter Weiss. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8288-9278-1 .

- Karl-Heinz Götze : Poetics of the Abyss and Art of Resistance. Basic pattern of Peter Weiss' imagery. VS, Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-531-12554-0 .

- Manfred Haiduk : The playwright Peter Weiss. Henschel, Berlin 1977.

- Raimund Hoffmann: Peter Weiss. Paintings - drawings - collages. Henschel, Berlin 1984 (also dissertation, Humboldt University Berlin).

- Achim Kessler: Create the unit! The figure constellation in the “Aesthetics of Resistance” by Peter Weiss. Edition Argument, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-88619-644-5 .

- Alfons Söllner : Peter Weiss and the Germans. The emergence of a political aesthetic against repression. West German Verlag, Opladen 1988 (plus habilitation thesis, FU Berlin).

- Christoph Weiß: Auschwitz in the divided world. Peter Weiss and the "investigation" in the Cold War (2 volumes). Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2001, ISBN 978-3-86110-245-8 (plus habilitation thesis, University of Mannheim 1999).

- Jörg Wollenberg : Pergamon Altar and Workers' Education : "Luxemburg-Gramsci Line - Prerequisite: Clarification of historical errors" (Peter Weiss), Hamburg 2005, VSA-Verlag, Socialism Supplement; [Jg. 32], Suppl. 5, ISBN 3-89965-924-4 (educational work with Peter Weiss)

- Jenny Willner: Word power. Peter Weiss and the German language. Konstanz University Press, Konstanz 2014, ISBN 978-3-86253-040-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Peter Weiss in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Peter Weiss in the German Digital Library

- Irmgard Zündorf: Peter Weiss. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Peter Weiss in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Life and work of Peter Weiss - biography, interpretations, short contents, bibliography (xlibris)

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from August 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) ( Ulrich Goerdten )

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki : It hit the heart of the era , FAZ , January 11, 2010

- René Schlott: From the end of all certainties - Auschwitz on stage on Zeitgeschichte-online October 2015

Institutions

- Peter Weiss Archive in the Archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- International Peter Weiss Society - publisher of the Peter Weiss yearbook and note sheets

- Peter Weiss Foundation for Art and Politics

- Peter-Weiss-Haus Education and Culture House Rostock

- Peter Weiss Library , Berlin-Hellersdorf

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Beutin, Klaus Ehlert, Wolfgang Emmerich, Helmut Hoffacker, Bernd Lutz, Volker Meid, Ralf Schnell, Peter Stein and Inge Stephan: Deutsche Literaturgeschichte. From the beginning to the present. 5th, revised edition. Stuttgart-Weimar: Metzler 1994, p. 595.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Vanishing Point. Novel. In: Peter Weiss. Prose 2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991, p. 164 (Peter Weiss. Works in six volumes. Ed. By Suhrkamp Verlag in collaboration with Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss, 2).

- ↑ Jochen Vogt: Peter Weiss. Reinbek: Rowohlt 1987, pp. 12-16. - Irene Weiss 'autobiography provides further insights into Peter Weiss' "nightmarish" childhood: Irene Weiss-Eklund: In search of a home. The eventful life of Peter Weiss' sister . Munich: Joke 2001.

- ↑ Irene Eklund-Weiss: In search of a home. The eventful life of Peter Weiss' sister . Munich: Scherz 2001. P. 51f.

- ↑ Kurt Oesterle : Tübingen, Paris, Plötzensee ... Peter Weiss' European topography of resistance, self-liberation and death in Rainer Koch, Martin Rector, Rainer Rother , Jochen Vogt (eds.): Peter Weiss Yearbook Volume 2, Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1993, ISBN 3-531-12426-9

- ^ Peter Roos : Genius Loci. Conversations about literature and Tübingen 2nd edition, Gunter Narr, Tübingen 1986, ISBN 3-87808-324-6 , pp. 19ff.

- ↑ a b The struggle for my existence as a painter. Peter Weiss in conversation with Peter Roos. With the collaboration of Sepp Hiekisch and Peter Spielmann. In: Peter Spielmann (ed.): The painter Peter Weiss. Pictures, drawings, collages, films Catalog for the exhibition at the Museum Bochum, March 8 to April 27, 1980. Berlin 1981, p. 14f.

- ↑ Alexander Weiss: Fragment , in: the same: Report from the clinic and other fragments . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978. pp. 7–44, here p. 18.

- ↑ Birgit Lahann: Peter Weiss . JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 2016, p. 35.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Farewell to the parents. Narration . In: Peter Weiss. Prose 2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991, p. 102 (Peter Weiss. Works in six volumes, 2).

- ↑ The struggle for my existence as a painter. Peter Weiss in conversation with Peter Roos. In: Peter Spielmann (ed.): The painter Peter Weiss. Pictures, drawings, collages, films Catalog for the exhibition at the Museum Bochum, March 8 to April 27, 1980. Berlin 1981, p. 21f.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Farewell to the parents. Narrative. In: Peter Weiss. Prose 2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991, p. 121 (Peter Weiss. Works in six volumes, 2).

- ↑ The struggle for my existence as a painter. Peter Weiss in conversation with Peter Roos. In: Peter Spielmann (ed.): The painter Peter Weiss. Pictures, drawings, collages, films Catalog for the exhibition at the Museum Bochum, March 8 to April 27, 1980. Berlin 1981, p. 23f.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Convalescence. In: Peter Weiss. Prose 2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991, p. 448 (Peter Weiss. Works in six volumes. Ed. By Suhrkamp Verlag in collaboration with Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss, 2). Quoted from: Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun. 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Alexander Weiss: Fragment , in: the same: Report from the clinic and other fragments . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1978. pp. 7–44, here p. 36.

- ↑ The exact date cannot be determined with certainty, cf. Hannes Bajohr / Angela Abmeier: Introduction , in: Peter Weiss: Letters to Henriette Itta Blumenthal. Edited by Angela Abmeier and Hannes Bajohr. Berlin: Matthes and Seitz 2011. pp. 5–49, here p. 11f.

- ↑ Jochen Vogt: Peter Weiss. Reinbek: Rowohlt 1987, p. 40.

- ^ Letter from Peter Weiss to Hermann Goldschmidt and Robert Jungk, April 28, 1941, in: Peter Weiss. Letters to Hermann Lewin Goldschmidt and Robert Jungk 1938–1980 . Leipzig: Reclam 1992. p. 157.

- ↑ Peter Weiss to Max Hodann , Alingsås, June 18, 1941. In: Peter Weiss yearbook for literature, art and politics in the 20th and 21st centuries. Volume 19 . Edited by Arnd Beise and Michael Hofmann. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2010. pp. 12–15, here p. 12f.

- ↑ See Hannes Bajohr / Angela Abmeier: Introduction , in: Peter Weiss: Briefe an Henriette Itta Blumenthal . Edited by Angela Abmeier and Hannes Bajohr, Berlin 2011, pp. 5–49, here pp. 32–37.

- ↑ Annie Bourguignon investigates Peter Weiss' relationship with his adopted home Sweden: The writer Peter Weiss and Sweden. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 1997.

- ↑ Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun. 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ On the intensive working relationship that Peter Weiss maintained with the Suhrkamp publishing house from 1960, see: Rainer Gerlach: The importance of the Suhrkamp publishing house for the work of Peter Weiss. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2005. - Rainer Gerlach (ed.): Siegfried Unseld / Peter Weiss: The exchange of letters. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2007.

- ↑ The aesthetic freedoms that the autobiographical author has allowed himself, his fictionalization processes and the broad field of intertextual references are revealed in the investigations: Axel Schmolke: The continuous work from one situation to another. Structural change and biographical readings in the variants of Peter Weiss' 'Farewell to Parents'. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2006. - Nils Göbel: “We cannot invent a form that is not present in us”. Genre issues, intertextuality and language criticism in “Farewell to Parents” and “Vanishing Point” by Peter Weiss. Marburg: Tectum 2007.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Notes on the historical background of our piece (1963) . In: Peter Weiss. Think in terms of opposites. A reader . Selected by Rainer Gerlach and Matthias Richter. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1986. pp. 154–158, here p. 155.

- ↑ Christine Frisch sums up the reception of the play: “Stroke of genius”, “Lehrstück”, “Revolutionsgestammel”: on the reception of the drama “Marat / Sade” by Peter Weiss in literary studies and on the stages of the Federal Republic of Germany, the German Democratic Republic and Sweden . Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell 1992.

- ↑ For the history of the origins and reception of the investigation, see the comprehensive two-volume study by Christoph Weiß: Auschwitz in the divided world: Peter Weiss and the “investigation” in the Cold War . St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2000.

- ↑ Klaus Wannemacher: "Mystical trains of thought were far from him". Erwin Piscator's first performance of 'Investigation' at the Freie Volksbühne . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 13 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2004. pp. 89-102.

- ^ So the edition of the Suhrkamp Verlag 1967/1968

- ↑ a b Jochen Vogt: Peter Weiss . Reinbek: Rowohlt 1987 (rowohlts monographien, 376), p. 127.

- ↑ Volker Lilienthal : literary criticism as political reading. Using the example of Peter Weiss's reception of the aesthetics of resistance . Berlin 1988. pp. 59-177. After: Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss . Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun. 2002, p. 233.

- ↑ The significance of Franz Kafka for Peter Weiss's oeuvre is revealed by Ulrike Zimmermann: Peter Weiss' dramatic adaptation of Kafka's “Trial” . Frankfurt am Main u. a .: Lang 1990. - Andrea Heyde: Submission and revolt. Franz Kafka in the literary work of Peter Weiss . Berlin: Erich Schmidt 1997.

- ↑ Martin Rector. In: Peter Weiss Yearbook 2 . Edited by Rainer Koch, Martin Rector, Rainer Rother, Jochen Vogt. Opladen: Westdeutscher 1993. S. 19. Quoted from: Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss . Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun. 2002, p. 158.

- ↑ Genia Schulz: Weiss, Peter . In: Metzler Authors Lexicon. German-speaking poets and writers from the Middle Ages to the present . Edited by Bernd Lutz. Stuttgart: Metzler 1986. pp. 626-629, here p. 627.

- ↑ "Spiegel" No. 19/1964, p. 113.

- ^ Playwrights with no alternatives. An interview with Peter Weiss [BBC interview by A. Alvarez]. In: Theater 1965. Chronicle and balance sheet of the stage year. Special issue of the German theater magazine "Theater heute" . Hanover: Friedrich 1965. p. 89.

- ^ Heinrich Vormweg Peter Weiss . Munich 1981. p. 104.

- ^ Botho Strauss: Picture book of the 1967/68 drama season . In: Theater 1968. Chronicle and balance sheet of the stage year . Hanover: Friedrich 1968. pp. 39–68, here p. 40.

- ^ Siegfried Melchinger : Revision or: Approaches to a theory of the revolutionary theater . In: Theater 1969. Special issue “Chronicle and balance sheet of a stage year” of the magazine “Theater heute” . Hanover: Friedrich 1969. pp. 83-89, here p. 89.

- ↑ On the subject of (political) writing and the self- image of the narrator as a writer and chronicler, see Jennifer Clare: Protexte. Interactions between literary writing processes and political opposition around 1968 . transcript, Bielefeld 2016, v. a. Pp. 151-176.

- ↑ Genia Schulz: Weiss, Peter . In: Metzler Authors Lexicon. German-speaking poets and writers from the Middle Ages to the present . Edited by Bernd Lutz. Stuttgart: Metzler 1986. pp. 626-629, here p. 628.

- ↑ The book sheds light on the eventful history of the reception of the aesthetics of resistance : "This trembling, tenacious, bold hope". 25 years of Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance . Edited by Arnd Beise, Jens Birkmeyer, Michael Hofmann. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2008. - The Aesthetics of Resistance has been available since 2007 in a 630-minute audio book adaptation that splits the central narrative role into a contemporary and a writing, reflective self and thus illuminates the text from different perspectives (director: Karl Bruckmaier . Munich: Der Hörverlag 2007).

- ↑ Jochen Vogt: Peter Weiss . Reinbek: Rowohlt 1987 (rowohlts monographien, 376), p. 27.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: Letters to Henriette Itta Blumenthal. Edited by Angela Abmeier and Hannes Bajohr. Berlin: Matthes and Seitz 2011. p. 13.

- ↑ Helmut Müssener: Exile in Sweden. Political and cultural emigration after 1933 . Munich 1974. p. 296f.

- ↑ For the meaning of the collage technique in Weiss' work see: Christine Ivanovic: The aesthetics of the collage in the work of Peter Weiss . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 14 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2005. pp. 69-100.

- ↑ Since then, the discussion with the author has shifted to white as an artistic “border crosser” as well as to various inter- media interrelationships and connections. See the exhibition catalogs and studies: Per drug: Peter Weiss. Måleri, collage, Teckning. 1933-1960. En utställning producerad av Södertälje Konsthall, Sverige. Södertälje 1976 (Swedish and German). - Peter Spielmann (ed.): The painter Peter Weiss. Pictures, drawings, collages, films . Berlin: Frölich and Kaufmann 1982. - Annette Meyer zu Eissen: Peter Weiss as a painter. Catalog for the exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bremen, January 16 to February 20, 1983 . Bremen 1983. - Raimund Hoffmann: Peter Weiss. Painting, drawings, collages. Berlin: Henschel 1984. - Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss and Jürgen Schutte (eds.): Peter Weiss. Life and work. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991. - Peter Weiss. Paintings, drawings, collages, film, theater, literature, politics. Directory of the exhibition of the Academy of the Arts February 24 to April 28, 1991 . Berlin: Academy of the Arts 1991. - Alexander Honold, Ulrich Schreiber (Hrsg.): The world of images of Peter Weiss . Hamburg: Argument 1995. - Peter Weiss - border crosser between the arts. Image - collage - text - film . Edited by Yannick Müllender, Jürgen Schutte, Ulrike Weymann. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang 2007.

- ^ Sverker Erk: "Looking for a language". Peter Weiss as a filmmaker. In: Peter Weiss. Life and work. An exhibition. Akademie der Künste, Berlin February 24 to April 28, 1991 . Edited by Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss and Jürgen Schutte. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1991. pp. 138-154, here pp. 139f.

- ↑ Erwin Leiser: God has no change. Memories . Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch 1993. p. 111. - Cf. Arnd Beise: Peter Weiss . Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun. 2002. pp. 19, 63.

- ^ Letter from Uwe Johnson to Siegfried Unseld, March 13, 1964, in: Uwe Johnson - Siegfried Unseld. The correspondence . Edited by Eberhard Fahlke and Raimund Fellinger. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1999. pp. 334f.

- ↑ Weiss' cinematic oeuvre came into the focus of research only late: Sepp Hiekisch-Picard: Der Filmmacher Peter Weiss. In: Rainer Gerlach. (Ed.): Peter Weiss . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1984. pp. 129-144. - Hauke Lange-Fuchs (Ed. In connection with the Office for Culture of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck and others): Peter Weiss and the film. Documentation. Lübeck, Essen 1986. - Jan Christer Bengtsson: Peter Weiss och kamerabilden . Stockholm 1989th - Beat Mazenauer: amazement and horror. Peter Weiss' cinematic aesthetic . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 5 . Edited by Martin Rector, Jochen Vogt […]. Opladen: Westdeutscher 1996. pp. 75-94.

- ↑ a b Michael Hofmann: Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance. Audiobook edition [review], in: Peter Weiss Jahrbuch. Volume 16. Edited by Arnd Beise, Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt in connection with the IPWG. Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2007, pp. 161-164

- ^ Five years later, in 1971, Weiss was denied entry to East Berlin on the grounds that he was an undesirable person . - See: culture mirror. "Unwanted" . In: Arbeiter-Zeitung . Vienna October 7, 1971, p. 8 , column 4 middle ( berufer-zeitung.at - the open online archive - digitized).

- ↑ See: Martin Rector: Peter Weiss' experimental film "Study IV: Liberation" . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 10 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2001. pp. 28-53.

- ↑ A detailed overview of the writings of Peter Weiss is offered by: Jochen Vogt, Peter Weiss . Reinbek: Rowohlt 1987 (rowohlts monographien, 376), pp. 147–150.

- ↑ The Divina Commedia project pursued by Peter Weiss between 1964 and 1969 and the drama Inferno found in the estate are dealt with by Yannick Müllender: Peter Weiss' 'Divina Commedia' project (1964–1969). "... can this still be described" - processes of self-understanding and social criticism . St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2007.

- ↑ Peter Weiss: On the trail of the unreachable. Essays and essays. Retrieved January 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Also: Harun Farocki: Conversation with Peter Weiss . In: Rainer Gerlach (Ed.): Peter Weiss . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1984. pp. 119-128.

- ↑ Also: Staffan Lamm: A strange bird. Encounters with Peter Weiss . In: Sinn and Form 49 (1997), No. 2, pp. 216-225.

- ↑ Peter Weiss on his 100th birthday. “I was a stranger wherever I went.” In: SWR2 , November 8, 2016, ( manuscript , PDF; 105.4 kB).

- ↑ Ulrich Engel : "Ricorda cosa ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz". Philosophical / theological investigations into literary / musical language against forgetting by Peter Weiss (1916–1982) and Luigi Nono (1924–1990). In: Paulus Engelhardt (Ed.): The language in the arts . Berlin, Hamburg, Münster: LIT 2008. pp. 67-85.

- ↑ CD supplement BIS-CD-646 1994, pp. 22-26

- ↑ More in detail: Kai Köhler, Kyung Boon Lee: Terror and Attraction of the Revolt. Comments on Jan Müller-Wieland's opera based on Peter Weiss' “Versicherung” . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 10 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2001. pp. 54-74. - Jan Müller-Wieland: “The Insurance” as an opera. Sporadic memories from the composer's perspective . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 12 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2003. pp. 49-58.

- ↑ In more detail: Claudia Heinrich: Comparative analysis of the libretto by Johannes Kalitzke for the opera production Inferno and the text of the play of the same name by Peter Weiss . In: Peter Weiss Yearbook. Volume 15 . Edited by Michael Hofmann, Martin Rector and Jochen Vogt. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2006. pp. 69-96.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Weiss, Peter |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Weiss, Peter Ulrich (full name); Sinclair (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Swedish writer, painter, graphic artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 8, 1916 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nowawes near Potsdam , German Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 10, 1982 |

| Place of death | Stockholm , Sweden |