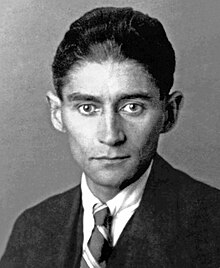

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (Czech sometimes František Kafka , Jewish name: אנשיל Ansel ; * July 3, 1883 in Prague , Austria-Hungary ; † June 3, 1924 in Kierling , Austria ) was a German-speaking writer . In addition to three fragments of the novel ( The Trial , The Castle and The Lost One ), his main work consists of numerous short stories .

Most of Kafka's works were only published after his death and against his will by Max Brod , a close friend and confidante whom Kafka had appointed as the administrator of the estate. Kafka's works are included in the canon of world literature. A separate word has been developed to describe his unusual way of portraying it: " kafkaesk ".

Life

origin

Franz Kafka's parents Hermann Kafka and Julie Kafka, née Löwy (1856–1934), came from middle-class Jewish merchant families. The family name is derived from the name of the jackdaw , Czech kavka , Polish kawka . The father came from the village of Wosek in southern Bohemia , where he grew up in simple circumstances. As a child he had to deliver the goods of his father, the butcher Jakob Kafka (1814–1889), to surrounding villages. Later he worked as a traveling salesman, then as an independent wholesaler with haberdashery goods in Prague. Julie Kafka belonged to a wealthy family from Podebrady , had a better education than her husband and had a say in his business, in which she worked up to twelve hours a day.

In addition to the brothers Georg and Heinrich, who died as small children, Franz Kafka had three sisters who were later deported , presumably to concentration camps or ghettos, where their traces are lost: Gabriele , called Elli (1889–1941?) , Called Valerie Valli (1890–1942?), And Ottilie “Ottla” Kafka (1892–1943?). Since the parents were absent during the day, all siblings were essentially raised by changing, exclusively female service personnel.

Kafka belonged to the minority of the Prague population whose mother tongue was German. Like his parents, he also spoke Czech. When Kafka was born, Prague was part of the Habsburg Empire in Bohemia, where numerous nationalities, languages and political and social currents mixed and coexisted right and wrong. For Kafka, a native of the German-speaking Bohemia , in reality neither Czech nor German, it was not easy to find a cultural identity.

He describes his relationship to his hometown as follows: “Prague does not let go. [...] This little mother has claws. "

While Kafka dealt extensively with his relationship with his father in letters, diaries and prose texts, the relationship with his mother was more in the background. However, there are a large number of relatives from the maternal line who can be found in Kafka's characters, including bachelors, eccentrics, Talmudic people and explicitly the country doctor Uncle Siegfried Löwy, who was the model for the story A Country Doctor .

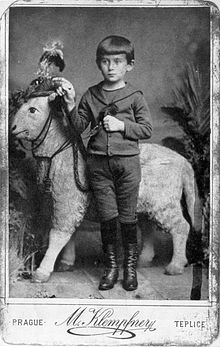

Childhood, youth and education

From 1889 to 1893 Kafka attended the German boys' school at the meat market in Prague. Then, in accordance with his father's wishes, he went to the Goltz-Kinsky Palace in Prague's old town, which was also German-speaking , and was located in the same building as his parents' gallantry shop. His friends in high school included Rudolf Illowý , Hugo Bergmann , Ewald Felix Příbram , in whose father's insurance he would later work, Paul Kisch and Oskar Pollak , with whom he remained friends until he was at university.

Kafka was considered a preferred student. Nevertheless, his school days were overshadowed by great fear of failure. Paternal threats, warnings from the domestic workers who looked after him, and extremely overcrowded classes evidently triggered massive anxiety in him.

Even as a schoolboy, Kafka was interested in literature. However, his early attempts are lost; he presumably destroyed them, as well as the early diaries.

In 1899, sixteen-year-old Kafka turned to socialism . Although his friend and political mentor Rudolf Illowy had been expelled from school for socialist activities, Kafka remained true to his convictions and wore the red carnation on his buttonhole. After passing the school leaving examination (Matura) in 1901 with “satisfactory”, the 18-year-old left Bohemia for the first time in his life and traveled to Norderney and Helgoland with his uncle Siegfried Löwy .

Kafka began his university studies from 1901 to 1906 at the German University in Prague , initially with chemistry; after a short time he switched to the legal direction; then he tried a semester of German studies and art history . In the summer semester of 1902, Kafka attended Anton Marty's lecture on basic questions in descriptive psychology . Then he even considered continuing his studies in Munich in 1903 in order to finally stick to the study of law. According to the program, he completed this after five years with a doctorate , which was followed by an obligatory one-year unpaid legal internship at the regional and criminal courts.

Kafka's most intense leisure activity was swimming from childhood until later years. In Prague, numerous so-called swimming schools had sprung up along the banks of the Vltava, which Kafka often visited. In his diary entry of August 2, 1914, he writes: "Germany has declared war on Russia - afternoon swimming school."

Working life

After almost a year of employment with the private insurance company “ Assicurazioni Generali ” (October 1907 to July 1908), Kafka worked from 1908 to 1922 in the semi-state “Workers' Accident Insurance Institution for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague”. He often referred to his service as "bread and butter".

Kafka's activity required precise knowledge of industrial production and technology. The 25-year-old made suggestions for accident prevention regulations. Outside of his service he showed political solidarity with the workers; he continued to wear a red carnation in his buttonhole at demonstrations that he attended as a passer-by. At first he worked in the accident department, later he was transferred to the insurance department. His tasks included writing instructions for use and technical documentation.

Since 1910, Kafka had been part of the operations department as a draftsman after he had prepared for this position by attending lectures on “Mechanical Technology” at the Technical University in Prague . Kafka issued notifications and prepared them when it was necessary to divide insured companies into hazard classes every five years . From 1908 to 1916 he was repeatedly sent on short business trips to northern Bohemia; he was often in the Reichenberg district administration . There he visited companies, gave lectures to entrepreneurs and attended court appointments. As an "insurance writer" he wrote articles for the annual report.

In recognition of his achievements, Kafka was promoted four times, in 1910 to draftsman, 1913 to vice secretary, 1920 to secretary, 1922 to senior secretary. Kafka wrote in a letter about his working life: "I don't complain about work as I do about the laziness of the swampy time". The “pressure” of the office hours, the stare at the clock, to which “all effect” is attributed, and the last minute of work as a “springboard for merriment” - this is how Kafka saw the service. He wrote to Milena Jesenská : "My service is ridiculous and pitifully easy [...] I don't know what I'm getting the money for."

Oppressive Kafka felt be (by the family expected) exposure to the parents' business to which the 1911 asbestos factory brother- in-law was added, which never wanted to legally flourish and tried to ignore the Kafka, although he was to her silent partner had made . Kafka's calm and personal dealings with the workers contrasted with his father's condescending boss behavior.

The First World War brought new experiences, as thousands of Eastern European Jewish arrived refugees to Prague. As part of the “Warrior Care”, Kafka took care of the rehabilitation and vocational retraining of seriously wounded people. He had been obliged to do this by his insurance company; Before that, however, they had claimed him to be an “irreplaceable specialist” and thus protected (against Kafka's intervention) from the front, after he had been classified as “fully serviceable” for the first time in 1915. Kafka experienced the downside of this esteem two years later when he fell ill with pulmonary tuberculosis and asked for retirement: the institution closed itself and only released him after five years on July 1, 1922.

Father relationship

The conflicted relationship with his father is one of the central and formative motifs in Kafka's work.

Even sensitive, reserved, yes shy and thoughtful, is how Franz Kafka describes his father, who worked his way up from a poor background and achieved something through his own efforts, as thoroughly vigorous and hard-working, but also rough, rumbling, self-righteous and despotic Merchant nature. Hermann Kafka regularly complains in violent tirades about his own barren youth and the well-cared for livelihoods of his descendants and employees, which he ensures alone with great effort.

The educated mother could have formed the opposite pole to her coarse husband, but she tolerated his values and judgments.

In his letter to his father , Kafka accuses him of having claimed a tyrannical power: “You can only treat a child as you were created yourself, with strength, noise and irascibility, and in this case it also seemed to you that is why very suitable because you wanted to raise a strong, courageous boy in me. "

In Kafka's stories, the father figures are often portrayed as powerful and also as unjust. The little story Elf Söhne from the country doctor volume shows a father who is deeply dissatisfied with all his offspring in different ways. In the novella The Metamorphosis , Gregor, who has been transformed into a vermin, is pelted with apples by his father and fatally injured in the process. In the short story The Judgment , the relatively strong and terrifying-looking father condemns his son Georg Bendemann to the "death of drowning" - he carries out what has been put forward in violent words in advance obedience to himself by jumping off a bridge.

Friendships

In Prague, Kafka had a constant circle of friends of about the same age, which formed during the first years of university ( Prager Kreis ). In addition to Max Brod , these were the later philosopher Felix Weltsch and the budding writers Oskar Baum and Franz Werfel .

Max Brod's friendship was of great importance to Kafka throughout his adult life. Brod invariably believed in Kafka's literary genius and repeatedly encouraged and urged him to write and publish. He supported his friend by arranging the first book publication with the young Leipzig Rowohlt Verlag . As Kafka's estate administrator, Brod prevented the burning of his novel fragments against his will.

A friendly relationship developed over many years with the Rowohlt publisher Kurt Wolff . Although Kafka's small works ( Contemplation , A Country Doctor , Der Heizer ) were not a literary success for the publisher, Kurt Wolff believed in Kafka's special talent and repeatedly encouraged him, and even insisted, to let him have pieces for publication.

Among Kafka's friends there is also Jizchak Löwy , an actor from a Hasidic Warsaw family, who impressed Kafka with his uncompromising attitude, with which he asserted his artistic interests against the expectations of his orthodox religious parents. Löwy appears as the narrator in Kafka's fragment Vom Jewish Theater and is also mentioned in the letter to the father .

Kafka had the closest family relationship with his youngest sister Ottla . It was she who stood by the brother when he fell seriously ill and urgently needed help and recovery.

Relationships

Kafka had an ambivalent relationship with women. On the one hand he was attracted to them, on the other hand he fled from them. Every step of his conquest was followed by a defensive reaction. Kafka's letters and diary entries give the impression that his love life was essentially a postal construct. His production of love letters increased to up to three a day to Felice Bauer. The fact that he remained unmarried to the end earned him the title “bachelor of world literature”.

In addition to his monastic way of working (he was forced to be alone and without ties in order to be able to write), impotence (Louis Begley) and homosexuality (Saul Friedländer) are suspected in literature as causes for Kafka's fear of attachment , although there is little evidence of this Find. The fact that women liked Kafka is no longer a secret, wrote literary critic Volker Hage in a 2014 Spiegel cover story about Kafka (issue 40/2014): “He had plenty of sexual experiences, not just with love that he could buy.” In addition: “Different as an outdated Kafka picture suggests, he was not a person turned away from life. ”Elsewhere, Hage writes:“ Real sexuality with its hard-to-control forces and inner conflicts obviously bothered him, something that is not unusual for sensitive people Tension, devoid of pathological features. In his diaries and travel notes, Kafka spoke in a remarkably impartial manner about the physical side of love. "

Kafka's first love was Hedwig Therese Weiler, who was born in Vienna in 1888 and was five years his junior. Kafka met her in the summer of 1907 in Triesch near Iglau (Moravia), where the two of them spent their holidays with relatives. Although the holiday acquaintance involved an exchange of letters, there were no further encounters.

Felice Bauer , who came from a middle-class Jewish background, and Kafka first met on August 13, 1912 in the apartment of his friend Max Brod. She was employed by Carl Lindström AG , which, among other things, Produced gramophones and so-called parlographs , and rose from shorthand typist to executive staff.

Reiner Stach gives a description of this first meeting between Franz and Felice: The letters to Felice mainly revolve around one question: to marry or to devote yourself to writing in self-chosen asceticism? After a total of around three hundred letters and six brief encounters, the official engagement took place in Berlin in June 1914 - but the engagement took place just six weeks later. This was the result of a momentous discussion on July 12, 1914 in the Berlin hotel " Askanischer Hof " between him and Felice in the presence of Felice's sister Erna and Grete Bloch . At this meeting, Kafka was confronted with statements in letters that he had made to Grete Bloch and that exposed him as unwilling to marry. In his diaries, Kafka speaks of the "court in the hotel". According to Reiner Stach, he provided the decisive images and scenes for the novel The Trial . However, a second marriage vow followed during a joint stay in Marienbad in July 1916, during which the two entered into a closer and happy intimate relationship. But this engagement was also broken again - after the outbreak of Kafka's tuberculosis (summer 1917).

After the final break with Felice, Kafka got engaged again in 1919, this time to Julie Wohryzek , the daughter of a Prague shoemaker. He had during a spa stay at the Pension Stüdl in 30 km from Prague village Schelesen met (Želízy). In a letter to Max Brod, he described her as “an ordinary and an astonishing figure. [...] Owner of an inexhaustible and unstoppable amount of the cheekiest jargon expressions, on the whole very ignorant, more funny than sad ”. This marriage promise also remained unfulfilled. During the first post-war summer they spent together, a wedding date was set, but postponed due to difficulties in finding accommodation in Prague. The two separated the following year. One reason may have been the acquaintance with Milena Jesenská , the first translator of his texts into Czech.

The journalist from Prague was a lively, self-confident, modern, emancipated woman of 24 years. She lived in Vienna and was in a divergent marriage with the Prague writer Ernst Polak . After the first contact by letter, Kafka paid a visit to Vienna. The man who had returned enthusiastically reported to his friend Brod about the four-day encounter, from which a relationship developed with a few encounters and, above all, an extensive correspondence. However, as with Felice Bauer, the old pattern was repeated with Milena Jesenská: approach and imaginary togetherness were followed by doubts and withdrawal. Kafka finally ended the relationship in November 1920, whereupon the correspondence broke off abruptly. The friendly contact between the two did not break off until Kafka's death.

In 1923, the year of inflation , Kafka met Dora Diamant in the Graal-Müritz spa . In September 1923, Kafka and Diamant moved to Berlin and forged marriage plans, which initially failed because of resistance from Diamond's father and finally because of Kafka's state of health. After he had withdrawn seriously ill in a small private sanatorium in the village of Kierling near Klosterneuburg in April 1924 , he was there by the destitute Dora Diamant, who was dependent on material support from Kafka's family and friends, until his death on April 3. Maintained June 1924.

The judgment

On the night of September 22nd to 23rd, 1912, Kafka managed to put the story The Judgment on paper in just eight hours in one go. According to a later literary scholarly view, Kafka found himself here thematically and stylistically in one fell swoop. Kafka was electrified by the act of writing, which has never been so intensely experienced ("This is the only way to write, only in such a context, with such a complete opening of the body and soul."). The undiminished effect of the story after repeated (own) reading - not only on the audience, but also on himself - strengthened his awareness of being a writer.

The judgment introduced Kafka's first longer creative phase; the second followed around two years later. In the meantime, as later, Kafka suffered a full year and a half of a period of literary drought. For this reason alone, an existence as a “bourgeois writer” remained for him, who can support himself and his own family with his work, in an unreachable distance throughout his life. His professional commitments as writing obstacles cannot alone have been the reason, Kafka often had his creative high phases especially in times of external crises or deterioration in general living conditions (e.g. in the second half of 1914 due to the outbreak of war). In addition, with his strategy of “maneuvering life” - which means: office hours in the morning, sleep in the afternoon, writing at night - Kafka also knew how to defend his freedom.

According to another popular thesis, Kafka's life and writing after the judgment was drawn up was characterized by the fact that he renounced ordinary life in order to devote himself entirely to writing. For this stylized sacrifice of life he himself provides ample material in his diaries and letters.

In contrast to the judgment , however, the later writing was often painful and hesitant for him; this reflects the following diary entry:

“Almost no word that I write fits the other, I hear the tinny consonants lining up and the vowels singing like exhibition negroes. My doubts are in a circle around every word, I see them earlier than the word, but what then! I don't see the word at all, I'll make that up. "

Judaism and Palestine Question

Through Kafka's circle of friends and primarily through Max Brod's commitment to Zionism , Kafka research was often confronted with the question of the writer's relationship to Judaism and with the controversies about the assimilation of Western Jews . In the letter to his father , on the one hand, Kafka complains in a lengthy passage about the “nothingness about Judaism” that was drummed into him in his youth, but at the same time expresses his admiration for the Yiddish actor Jizchak Löwy . His sympathy for Eastern Jewish culture has been documented several times. As a writer, he placed a taboo on everything “explicitly Jewish [...] : the term does not appear in his literary work”. Nevertheless, his biographer Reiner Stach interprets the air dogs in Kafka's parable Researches a Dog as the Jewish people in the Diaspora.

A telling picture of his fragile religious and individual self-assessment is shown in a diary entry from January 8, 1914: “What do I have in common with Jews? I have little in common with myself and should be very still, satisfied that I can breathe in a corner ”.

At times Kafka was determined to emigrate to Palestine and learned Hebrew intensively . His deteriorating health prevented him from the seriously planned move in 1923 . Reiner Stach sums up: "Palestine remained a dream that his body ultimately ruined."

Sickness and death

In August 1917, Franz Kafka suffered a night hemorrhage . It was a pulmonary tuberculosis detected; a disease that was not curable at the time. The symptoms initially improved, but in autumn 1918 he fell ill with the Spanish flu , which caused pneumonia for several weeks. After that, Kafka's health deteriorated from year to year, despite numerous long spa stays, among others. in Schelesen (now the Czech Republic ), Tatranské Matliare (now Slovakia ), Riva del Garda ( Trentino in the Dr. von Hartungen sanatorium), Meran (1920) and Graal-Müritz (1923). During his stay in Berlin in 1923/24, tuberculosis also spread to the larynx, Kafka gradually lost his ability to speak and was only able to take food and fluids with pain. During a stay at the Wienerwald sanatorium in April 1924, Dr. Hugo Kraus, a family friend and head of the pulmonary hospital, was definitely diagnosed with larynx tuberculosis. As a result of the progressive emaciation, the symptoms could only be alleviated; an operation was no longer possible due to the poor general condition. Franz Kafka left and died on June 3, 1924 in the Hoffmann Sanatorium in Kierling near Klosterneuburg at the age of 40. Heart failure was found to be the official cause of death . He was buried in the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague- Žižkov . The slender cubist tombstone of Franz Kafka and his parents with inscriptions in Hebrew is to the right of the entrance, about 200 meters from the gatehouse. On the cemetery wall opposite the grave, a memorial plaque in Czech commemorates Max Brod.

On the question of nationality

Kafka spent the bulk of his life in Prague, which until the end of World War I in 1918 to the multi-ethnic state of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy of Austria-Hungary was one and after the First World War, the capital of the newly founded Czechoslovakia was. The writer himself described himself as a German native speaker in a letter (“German is my mother tongue, but Czech goes to my heart”). The German-speaking population in Prague, which made up about seven percent, lived in an "island-like seclusion" with their language, also known as " Prague German ". Kafka also meant this isolation when he wrote in the same letter: "I have never lived among the German people." He also belonged to the Jewish minority . Even at school there were fierce arguments between Czech and German-speaking Prague residents. For Kafka - during the First World War, for example - the political German Reich remained far away and found no expression in his work. Evidence for the self-view of an Austrian nationality cannot be found either. Nor did Kafka have any connection to Czechoslovakia, which was founded in 1918. In contrast to his German-Bohemian superiors, Kafka kept his position in the workers' insurance company after 1918 due to his knowledge of the Czech language and his political reluctance and was even promoted. Since then he has also used the Czech form of the name František Kafka in official correspondence in the Czech language , unless he abbreviates the first name, as is usually the case.

The milieu in which Kafka grew up, that of the assimilated Western Jews, was emphatically loyal to the emperor, which is why patriotism was accepted unquestionably. Kafka himself took part in a patriotic event at the beginning of the First World War and commented on it: "It was wonderful". He was referring to "the magnitude of the patriotic mass experience" that "overwhelmed him". The fact that he subscribed considerable sums of war bonds also fits this picture. After the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy , anti-German and anti-Semitic resentments, which had hardly been veiled before, intensified in the Prague majority population, and Kafka also took advantage of this and took it as an opportunity to concretise his own migration plans, but without the Zionist ideologues from his environment (e . Max Brod) to get closer: “All afternoons I am now in the streets, bathing in hatred of Jews. I have now heard the Jews mention Prašivé plemeno [mangy brood]. Isn't it a matter of course that one moves away from where one is so hated (Zionism or popular sentiment is not necessary for this)? "

Conjectures about Kafka's sexual orientations

A statement from Kafka's diary reads: “Coitus as a punishment for the happiness of being together. To live as ascetically as possible, more ascetic than a bachelor, that is the only way for me to endure marriage. But you? ”Sexual encounters with his friends Felice Bauer and Milena Jesenka seem to have been frightening for him. On the other hand, Kafka's visits to brothels are known. At the same time, Kafka was a man with diverse platonic relationships with women in conversations and letters, especially during his spa stays.

In diaries, letters and in his works women are often described as unfavorable. Worth mentioning here is his unusual view of the relationship between men and women. The women are strong, physically superior, and sometimes violent. The maid, whom Karl Rossmann downright raped, or the factory owner's daughter Klara, who forces an unequal fight on him, or the monstrous singer Brunelda, to whose service he is forced to appear, appears in the missing . The women in the castle are predominantly strong and coarse-bodied (with the exception of the delicate but headstrong Frieda).

Male figures, however, are described several times as beautiful or charming. Karl Rossmann, the missing man , the beautiful boy, or in the castle the beautiful, almost androgynous messenger Barnabas and the lovely boy Hans Brunswick, who wants to help K.

Homoerotic Approaches

In Kafka's diary entries, his friendships with Oskar Pollak , Franz Werfel and Robert Klopstock are discussed with enthusiastic, homoerotic echoes.

In his work, homoerotic allusions clearly emerge. Already in one of his early larger stories the description of a fight , when the narrator and an acquaintance on a hill have a fantastic conversation about their mutual relationship and the resulting wounds. Karl Rossmann in the missing develops an almost incomprehensible attachment to the stoker he just met on the ship. The stoker had invited him to his bed. When saying goodbye, he doubts that his uncle would ever be able to replace this stoker for him.

In the castle , K. penetrates into civil servant Bürgel's room. In his tiredness he went to bed with the officer and was welcomed by him. During his sleep he dreams of a secretary as a naked god.

Sadomasochistic fantasies

In a letter to Milena Jesenska in November 1920, he wrote: "Yes, torture is extremely important to me, I am concerned with nothing other than being tortured and tortured."

In his diary of May 4, 1913, he noted:

"Constantly the idea of a wide selcher knife that rushes into me from the side with mechanical regularity and cuts very thin cross-sections that fly away almost curled up during the fast work"

A sadomasochistic moment already appears in the transformation . The giant beetle fights for the image of a woman with fur, reminiscent of the novel Venus in Furs by Sacher-Masoch .

In the penal colony , torture with the help of a "peculiar device" is the main topic. There is a shift between victim (naked convict) and perpetrator (officer). The officer initially believes in the cathartic effect of the torture by the sophisticated machine that he demonstrates to the traveler. In his emotion, the officer hugs the traveler and lays his head on his shoulder. But the traveler cannot in any way be convinced of this kind of jurisprudence by torture and thus causes a verdict on the machine to which the officer voluntarily submits by laying himself under the working machine. But the officer does not recognize his own fault.

The beating scene in the process is an outspoken sado- maso staging. There are two guards who were absent because of K. They are said to be beaten naked with a rod by a half-naked flogger in black leather clothing. This procedure obviously takes over two days.

Even the short stories like The Vulture and The Bridge contain tormenting, bloodthirsty depictions.

Influences

From literature, philosophy, psychology and religion

Kafka saw in Grillparzer , Kleist , Flaubert and Dostojewski his literary "blood brothers". Unmistakable is the influence of Dostoyevsky's novel Aufzüge aus dem Kellerloch , which anticipates many peculiarities of Kafka's work, but also, for example, the idea of the transformation of man into an insect in the story The Metamorphosis .

According to Nabokov , Flaubert exercised the greatest stylistic influence on Kafka; Like him, Kafka abhorred pleasing prose, instead he used language as a tool: “He liked to take his terms from the vocabulary of lawyers and scientists and gave them a certain ironic accuracy, a process with which Flaubert had also achieved a unique poetic effect . "

As a high school graduate, Kafka dealt intensively with Nietzsche . Thus spoke Zarathustra especially seems to have captivated him.

Kafka writes about Kierkegaard in his diary: "He confirms me like a friend."

Sigmund Freud's theories on oedipal conflict and paranoia may have come to Kafka due to time, but he does not seem to have been interested in these topics.

Kafka has dealt intensively with the Jewish religion through extensive reading . He was particularly interested in religious sagas, stories and instructions that were originally passed down orally. There was personal contact with the Jewish religious philosopher Martin Buber .

However, Kafka was also closely related to the philosophy of Franz Brentano, which was present in Prague, about whose theories he and his friends Max Brod and Felix Weltsch heard lectures by Anton Marty and Christian von Ehrenfels at the Charles University. The empirical psychology developed by the Brentanists and its questions had a lasting impact on the poetics of the young Kafka.

From the cinema, the Yiddish theater and from amusement facilities

In a letter from December 1908, Kafka said: "[...] how else could we keep ourselves alive for the cinematograph". In 1919 he wrote to his second fiancée, Julie Wohryzek , that he was “in love with the cinema”. Kafka was obviously less impressed by the film plot (corresponding statements are missing in his writings); rather, his texts themselves reflect a film-technical point of view. His storytelling develops its special character through the processing of cinematic movement patterns and subjects . It lives from the grotesque sequences of images and exaggerations of early cinema, which appear here in a linguistically condensed literary form. The film is omnipresent in Kafka's stories: in the rhythm of urban traffic, in chases and doppelganger scenes and in gestures of fear. These elements can be found especially in the fragment of the novel The Lost One .

Many of the elements mentioned were also included in the hearty performances of the Yiddish theater from Lemberg , which Kafka often attended and whose members he was friends with; Kafka had a strong impression of authenticity here . Two small works from the estate attest to Kafka's interest in the Yiddish language and culture in Eastern Europe, namely On the Jewish Theater and an introductory lecture on jargon .

Until around 1912, Kafka also actively participated in the nightlife with cabaret shows. This included visits to cabarets , brothels , variety shows and the like. A number of his late stories are set in this milieu; see First Sorrow , A Report for an Academy , A Hunger Artist , Josephine, the Singer, or The People of Mice .

Works and classification

Franz Kafka can be seen as a representative of literary modernism . He stands next to writers like Rilke , Joyce or Döblin .

The fragments of the novel

As in a nightmare, Kafka's protagonists move through a labyrinth of opaque conditions and are at the mercy of anonymous powers. The literary criticism speaks of a "dream logic". The courthouses in The Trial consist of a widely ramified tangle of confusing rooms, and also in Der Verschollene (published by Brod under the title America ) are the strangely disconnected locations - including a ship, a hotel, the "Oklahoma Nature Theater" and the Apartment of Karl Roßmann's uncle, the hero - gigantic and unmanageable.

In particular, the relationships between the people involved remain unclear. In the castle , Kafka creates doubts about the position of the protagonist K. as a "land surveyor" and the content of this term itself, thus creating room for interpretation. In the course of the novel, K., and with him the reader, only learns fragmentarily more about the officials of the castle and their relationships with the villagers. The omnipresent, but at the same time inaccessible, fascinating and oppressive power of the castle over the village and its people becomes more and more evident. Despite all his efforts, to feel at home in this world and to clarify his situation, K. has no access to the relevant bodies in the lock management, as well as the accused Josef K. in the process never gets only the indictment to face.

Only in the fragment of the novel Der Verschollene - Das Schloss and Der Trial remained unfinished - does the vague hope remain that Roßmann can find permanent security in the almost limitless, paradisiacal "natural theater of Oklahoma".

The stories

In many of Kafka's stories, e.g. B. The construction , research of a dog , little fable , the failure and the futile striving of the characters is the dominant theme, which is often portrayed tragically and seriously, but sometimes also with a certain comedy.

An almost constant topic is the hidden law, against which the respective protagonist unintentionally violates or which he does not reach ( Before the law , In the penal colony , The blow to the yard gate , On the question of the laws ). The motif of the code hidden from the protagonist, which controls the processes, can be found in the novel fragments Process and Schloss and in numerous stories.

In his incomparable style, especially in his stories, Kafka describes the most unbelievable facts extremely clearly and soberly. The cool, meticulous description of the seemingly legal cruelty in the penal colony or the transformation of a person into an animal and vice versa, as in The Metamorphosis or A Report for an Academy , are characteristic.

Kafka published three anthologies during his lifetime. These are Contemplation 1912 with 18 small prose sketches, Ein Landarzt 1918 with 14 stories and Ein Hungerkünstler 1924 with four prose texts.

Hidden topics

In addition to the great themes of Kafka, i.e. the relationship with his father, impenetrable large bureaucracies or the cruelty of a system, there are a number of other motifs in his works that appear again and again rather inconspicuously.

Mention should be made here of the reluctance to perform and work.

The officials of the castle in their multiple tiredness and illness, which even causes them to receive their parties in bed and in the morning to try to fend off the work assigned to them. Similar to the lawyer Huld from the process .

The miners in A Visit to the Mine , who stop work all day to watch the engineers.

The city coat of arms tells of the construction of a gigantic tower. But it is not started. The prevailing opinion is that the architecture of the future is better suited for the actual construction of the tower. But later generations of construction workers recognize the pointlessness of the project. When building the Great Wall of China , as the title suggests, a major construction project is also the topic. But the execution, initially intentional and often weighed, always consists of gaps in wall segments. Since nobody overlooks the overall project, it ultimately remains undetected whether it would even be capable of a real protective function.

In the test a servant occurs that does not work and also has not urges. Other servants in the manor also appear to be idle. An examiner comes along and certifies that doing nothing and not knowing is exactly the right thing to do.

In the large float a famous swimmer occurs to the big celebrations confuse his person and claiming to not swim, even though he could have some time to learn, but it had not found any opportunity.

Humorous moments

As dark as the novel The Trial is, there are small humorous interludes here. While reading the novel, Kafka is said to have laughed out loud many times. The judges study pornographic magazines instead of legal texts, they let women bring them to them like magnificent dishes on a tray, a courtroom has a hole in the floor, and every now and then a defense attorney hangs his leg in the room below. Then a slapstick scene when old officials keep throwing newly arriving lawyers down the stairs but keep climbing them.

Sometimes there are only small scenes, like in the castle when the land surveyor meets his messenger on a wintry night, who hands him an important document from Klamm. When he is about to read it, his assistants stand next to him and, in a useless way, take turns raising and lowering their lights over K.'s shoulder. Or how the surveyor throws the two assistants out the door, but they quickly come back in through the window.

The little story of Blumfeld, an older bachelor, includes slapstick and persecution. The older bachelor is followed by two small white balls that cannot be shaken off. Two eager little girls from the house want to take care of the two balls.

Kafka's narrative structure and choice of words

At first glance, there seems to be a conflict of tension between topic and language. Stylistic renunciation appears as Franz Kafka's aesthetic principle. The shocking events are reported in unadorned, sober language. Kafka's style is without extravagance, alienation and commentary. Its aim is to increase the effect of the text as much as possible by limiting the use of language. Kafka was very successful in his effort to achieve a highly objective style. Due to the factual, cool reporting style, the astonishing and inexplicable are accepted as fact by the reader. The tighter the wording, the more the reader is stimulated to understand what is being told. The narrated incident is suggested to be so real that the reader does not even get to think about its (im) possibility.

It was Kafka's goal to adequately portray, instead of alienating, that is to say, to be poor in language. This relationship to language results in Kafka's characteristic tendency towards an epic without a commenting or omniscient narrator. The apparent simplicity of Kafka’s use of words is the result of a strict choice of words, the result of a concentrated search for the most catchy and direct expression in each case. As Franz Kafka's highest poetic virtue, Max Brod emphasized the absolute insistence on the truthfulness of expression, the search for the one, completely correct word for a thing, this sublime faithfulness to the work that was not satisfied with anything that was even the least bit defective.

Another stylistic device of Kafka is to expose the whole future disturbing problematic in a concentrated manner in the first movement of the work, as for example in The Metamorphosis , The Disappeared or The Trial .

With his style and his disconcerting content, Kafka does not simply recreate an attitude towards life, but creates a world of its own with its own laws, the incomparability of which the term “Kafkaesque” tries to paraphrase.

interpretation

The interpreters' interest in interpreting after 1945 is perhaps due to the fact that his texts are open and hermetic at the same time: On the one hand, they are easily accessible through language, action, imagery and relatively small size; on the other hand, however, its depth can hardly be fathomed. Albert Camus said: “It is the fate and perhaps also the greatness of this work that it presents all possibilities and confirms none.” Theodor W. Adorno says about Kafka's work: “Every sentence speaks: interpret me, and nobody will tolerate it. "

Apart from the criticism inherent in the text , different interpretations of Kafka's work show, among other things. in the following directions: psychological (as with corresponding interpretations by Hamlet , Faust or Stiller ), philosophical (especially on the school of existentialism ), biographical (e.g. through Elias Canetti in The Other Process ), religious (a dominant aspect of the early Kafka reception, which is seen as questionable today, among others by Milan Kundera ) and sociological (i.e. examining the socio-critical content). An important question of the interpretation of Kafka's works is that of the influence of the Jewish religion and culture on the work, which was already answered by Gershom Scholem to the effect that Kafka can be assigned to Jewish rather than German literary history. This hint of interpretation was widely used by Karl E. Grözinger in his publication Kafka and the Kabbala. The Jewish in the work and thought of Franz Kafka. Berlin / Vienna added in 2003. His research has shown that entire novels such as The Trial or The Castle are deeply anchored in Jewish religious culture, without which the work can hardly be adequately understood. Even if disputed by some modern authors, Grözinger's views have been widely accepted.

Kafka brings many of the characters in his novels and stories in relation to Christianity: In the trial Josef K. looks very closely at a picture of the burial of Christ , and in the judgment Georg Bendemann is addressed by the operator with "Jesus!" On the way to his self-sacrifice. In the castle , the surveyor K., like Jesus, spends the first night of his (novel) life in an inn on a straw mattress Christianity became more important than Judaism ( Acts of the Apostles Acts 13.2 EU ).

Particularly characteristic of Kafka are the frequent repetitions of motifs, especially in the novels and many of the most important stories, sometimes across all creative periods. These repetitive motifs form a kind of network over the entire work and can be made fruitful for a binding interpretation of the same. Two of the most important repetition motifs are the motif “bed”, an unexpectedly frequent place of residence and encounter of characters, where or in which for many protagonists of the texts the disaster begins and continues, and the motif “door” in the form of an argument around their passing (the best-known example is the gateway to the law in the text Before the Law , the so-called “doorkeeper legend”).

Regardless of the respective interpretations, the term Kafkaesque is used to denote an atmosphere that is “mysteriously threatening” , which, according to Kundera, “is to be seen as the only common denominator of (both literary and real) situations that cannot be characterized by any other word are and for which neither political science nor sociology nor psychology provide a key. "

Impact history

Literary connoisseurs such as Robert Musil , Hermann Hesse , Walter Benjamin and Kurt Tucholsky were already familiar with Kafka in the 1920s. His work did not achieve world fame until after 1945, initially in the USA and France, and in the 1950s in German-speaking countries as well. Today Kafka is the most widely read author in the German language. The Kafka reception extends into everyday life: In the 1970s there was an advertising slogan "I drink Jägermeister because I haven't cracked Kafka's lock."

Kafka's own perspective on his work

During his lifetime, Kafka was unknown to the general public.

Kafka quarreled with himself. His doubts went so far that he instructed his administrator Brod to destroy the texts that had not yet been published (including the now famous fragments of the novel). In the second order addressed to Brod on November 29, 1922, Kafka declared:

“Of all that I have written, only the books are valid: Judgment, Stoker, Metamorphosis, Penal Colony, Country Doctor and the story: Hunger artists. (The few copies of the 'Contemplation' may remain, I don't want to bother anyone to crush it, but nothing should be reprinted from it.) When I say that those 5 books and the story apply, I don't mean that I I wish they could be reprinted and handed over to future times, on the contrary, should they get lost completely, this corresponds to my actual wish. Only, since they are already there, I do not prevent anyone from receiving them if they feel like it. "

Today there is broad consensus in literary circles that Brod made a beneficial decision when he ignored the last will of his friend and published his work.

However, Kafka himself destroyed a part of his texts that could not be determined more precisely, so that Brod came too late.

Kafka as a banned author

During the period from 1933 to 1945, Kafka was listed in the relevant list of banned authors during the Nazi era as a producer of “harmful and undesirable written material”. Like many others, his works fell victim to the book burns .

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) did not rehabilitate Kafka after the Second World War , but classified him as " decadent ". In the novel The Trial one found undesirable echoes of the denunciations and show trials in the states of the Eastern Bloc . In general, Czechoslovakia hardly identified with Kafka at the time of communism , probably also because he wrote almost exclusively in German.

In May 1963, on the initiative of Eduard Goldstücker , the Czechoslovakian Writers' Union held an international Kafka conference on the 80th birthday of the writer in Liblice Castle near Prague, which dealt with the writer , who was still largely rejected in the Eastern Bloc at the time, and with the thematic focus on alienation . He has been recognized by many speakers. This conference is considered to be a starting point for the Prague Spring of 1967/68. But as early as 1968 after the crackdown on the Prague Spring, Kafka's works were banned again. The importance of the conference was dealt with in a conference in 2008.

Today's Czech Republic

With the opening of the Czech Republic to the west and the influx of foreign visitors, Kafka's local importance grew. In 2018, a doctoral student from Charles University in Prague succeeded in rediscovering and publishing a contemporary description of the work of Franz Kafka's short stories Before the Law and A Report for an Academy, which had previously been believed to be lost .

In October 2000 a jury announced that a three-meter-high bronze monument would be erected in the old town between the Spanish synagogue and the Church of the Holy Spirit. The Prague Franz Kafka Society is dedicated to the works of Kafka and tries to revive Prague's Jewish heritage. In the Kafka year 2008 (125th birthday), Kafka was recognized by the city of Prague for promoting tourism. There are many places where Kafka encounters, bookshops and souvenir items of all kinds. Since 2005, the Kafka Museum on the Lesser Town of Prague (Cihelná 2b) has shown the exhibition The City of K. Franz Kafka and Prague .

International impact

As early as 1915, Kafka was indirectly awarded the “ Theodor Fontane Prize for Art and Literature ”: The official award winner Carl Sternheim passed the prize money on to the still largely unknown Kafka.

The great influence of Kafka on Gabriel García Márquez is guaranteed . In particular, from Kafka's story The Metamorphosis , García Márquez, according to his own admission, has taken the courage to develop his “ magical realism ”: Gregor Samsa's awakening as a beetle, according to García Márquez himself, showed his “life a new path, already with the first line, which today is one of the most famous in world literature ”. Kundera recalls an even more precise statement from García Márquez about Kafka's influence on him in his book Verbei Vermächtnisse (p. 55): “Kafka taught me that you can write differently.” Kundera explains: “Different: that meant, by going beyond the bounds of the probable. Not (in the way of the romantics ) to escape the real world, but to understand it better. "

In a conversation with Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt , the Kafka biographer Reiner Stach describes Samuel Beckett as “Kafka's legacy”.

Among contemporary writers, Leslie Kaplan often refers to Kafka in her novels and in statements about her way of working in order to depict the alienation of people, the murderous bureaucracy, but also the freedom that thinking and writing in particular open up.

Kafka also finds great admiration beyond artistic criteria. For Canetti Kafka is a great poet because he “expressed our century in the purest possible way”.

Kafka's work stimulated implementation in the visual arts:

- K - art to Kafka . Exhibition on the 50th anniversary of death. Bucherstube am Theater, Bonn 1974.

- Hans Fronius . Art to Kafka . With a text by Hans Fronius. Introduction by Wolfgang Hilger. Captions Helmut Strutzmann. Edition Hilger and Lucifer Verlag in the Kunsthaus Lübeck, Vienna and Lübeck 1983, ISBN 3-900318-13-1 .

Dispute over the manuscripts

Before his death, Kafka had asked his friend Max Brod to destroy most of his manuscripts. Brod resisted this will, however, and saw to it that many of Kafka's writings were published posthumously. In 1939, shortly before the German troops marched into Prague, Brod managed to save the manuscripts to Palestine . In 1945 he gave them to his secretary Ilse Ester Hoffe , as he noted in writing: "Dear Ester, In 1945 I gave you all of Kafka's manuscripts and letters that belong to me."

Hope sold some of these manuscripts, including letters and postcards, the manuscript describing a struggle (today in the possession of the publisher Joachim Unseld ) and the manuscript for the novel Der Process , which was sold to Heribert Tenschert in 1988 at the London auction house Sotheby’s for the equivalent of 3.5 million marks was auctioned. This can now be seen in the permanent exhibition of the Modern Literature Museum in Marbach. Hoffe gave the remaining manuscripts to her two daughters Eva and Ruth Hoffe while she was still alive.

After the death of their mother in 2007, Eva and Ruth Hoffe agreed to sell the manuscripts to the German Literature Archive in Marbach , which led to a dispute between the two sisters and the literary archive on the one hand and the State of Israel, which had the rightful place of Kafka's manuscripts in the National Library of Israel sees, on the other hand, led. Israel justifies its claim to the manuscripts with a paragraph from Max Brod's will, although Ester Hoffe had received the manuscripts as a gift from Max Brod and also gave them to her daughters and not bequeathed them. Since 1956 all manuscripts still in Hoffe's possession have been in bank vaults in Tel Aviv and Zurich . On October 14, 2012, an Israeli family court ruled that the manuscripts were not the property of the Hoffees. Kafka's estate is to go to the Israeli National Library. Eva Hoffe announced that she would appeal. On August 7, 2016, the Israeli Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the appeal and awarded the estate to the Israeli National Library. David Blumenberg, the library director, then announced that the collection would be made available to the general public. As part of the legacy was also kept in UBS bank safes in Zurich, a further court decision was necessary for the execution of the judgment. Swiss recognition of the Israeli judgment, which the Zurich District Court issued at the beginning of April 2019, was necessary . On this basis, UBS was only able to hand over the contents of the safes of the Israeli National Library in July 2019.

factories

Published in lifetime

- 1908 - contemplation . (with eight prose texts, all of which were included in 1913 in the volume of prose viewing ), Hyperion issue 1, January 1908, pp. 91–94.

- 1909 - A ladies' breviary .

- 1909 - Conversation with the prayer .

- 1909 - conversation with the drunk .

- 1909 - The plane in Brescia .

- 1911 - Richard and Samuel .

- 1912 - Big noise .

- 1913 - contemplation . (with 18 prose texts, including: The excursion into the mountains , The sudden walk ).

- 1913 - The verdict .

- 1913 - The stoker . (First chapter of the fragment of the novel The Lost One ).

- 1915 - The transformation . ; 1916 - The Youngest Day series , Verlag Kurt Wolff , Leipzig, with a dust jacket drawing by Ottomar Starke .

- 1915 - Before the law . Part of the novel fragment The Trial and the volume Ein Landarzt .

- 1917 - The bucket rider .

- 1918 - the murder . (1918; earlier version of A Fratricide , written in 1919 and published as part of the Landarztband ).

- 1918 - A country doctor .

- 1919 - In the penal colony .

- 1920 - A country doctor . (Anthology with 14 prose texts, including: A country doctor (story), Before the law , An imperial message , A fratricide , A report for an academy )

- 1924 - A hunger artist . (Story from 1922 and title of the anthology with three further prose texts: First Sorrow , A Little Woman and Josephine, the Singer or The People of Mice ).

All 46 publications (in some cases multiple publications of individual works) during Franz Kafka's lifetime are listed on pages 300 ff. In Joachim Unseld : Franz Kafka. A writer's life. The history of his publications. ISBN 3-446-13554-5 .

Published posthumously

Stories and other texts

The year of creation in brackets.

|

|

The fragments of the novel

- 1925 - The trial . Minutes 1914/15; Deviating from Kafka's spelling for the novel fragment, Der Proceß or Der Prozess are used.

- 1926 - The castle . Minutes 1922; Novel fragment.

- 1927 - The missing . First drafts in 1912 under the title “Der Verschollene”; published by Brod under the title America , today the original title name is more common again; Novel fragment.

Work editions

- Max Brod (ed.): Collected works. S. Fischer, Frankfurt / New York 1950–1974 (also known as the Brod edition , today text-critical obsolete).

- Jürgen Born, Gerhard Neumann , Malcolm Pasley, Jost Schillemeit (eds.): Critical edition. Writings, diaries, letters. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1982 ff. (Also referred to as the Critical Kafka Edition , KKA).

- Hans-Gerd Koch (Ed.): Collected works in 12 volumes in the version of the manuscript. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1983 ff. (Text identical to the text volumes of the critical edition ).

- Roland Reuß , Peter Staengle (ed.): Historical-critical edition of all manuscripts, prints and typescripts. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt / Basel 1995 ff. (Also referred to as Franz Kafka edition , FKA, not yet completed).

Radio play adaptations

- In the penal colony with Peter Simonischek . Director: Ulrich Gerhardt . Production: BR radio play and media art 2007. Running time 73 min. As a podcast / download in the BR radio play pool.

- The Process , radio play in 16 parts. With Rufus Beck , Samuel Finzi , Corinna Harfouch , Jürgen Holtz , Milan Peschel , Jeanette Spassova , Thomas Thieme , Manfred Zapatka . Director: Klaus Buhlert . Production: BR radio play and media art 2010, running time 10 hours. As a podcast / download in the BR radio play pool.

- The castle , radio play in 12 parts. With Michael Rotschopf (narrator), Devid Striesow (K.), Werner Wölbern (observer from the castle), Steven Scharf (Schwarzer), Peter Kurth (landlord from Brückenhof), Corinna Harfouch (landlady from Brückenhof), Stefan Zinner (landlord from Herrenhof ), Jens Harzer (Arthur / Jeremias), Gerti Drassl (Frieda), Sandra Hüller (Olga), Samuel Finzi (Momus / Oswald), Moritz Kienemann (Barnabas), Dieter Fischer (Lasemann), Wowo Habdank (Gerstäcker), Deleila Piaskov (Ms. 1), Margit Bendokat (landlady of the Herrenhof), Wolfram Berger (head), Götz Schulte (teacher), Anna Drechsler, Benedict Lückenhaus, Bibiana Beglau (Amalia), Johannes Silberschneider (Bürgel), Stefan Wilkening (Erlanger). Editing, composition and direction: Klaus Buhlert , production: BR Hörspiel und Medienkunst 2016. After the first broadcast (January 15 - April 3, 2017) the individual parts are available as podcasts / downloads in the BR radio play pool.

Audio books

- Sven Regener reads Franz Kafka: The Trial , unabridged reading. Roof Music, Bochum 2016, ISBN 978-3-86484-399-0 .

- Sven Regener reads Franz Kafka: America , unabridged reading. Roof Music, Bochum 2014, ISBN 978-3-86484-103-3 .

- Onslaught against the border - diaries from 1910 to 1922. Read by Bodo Primus , mOceanOTonVerlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-86735-237-6 .

- The transformation . 2 CDs, running time 120 min., Spoken by Rainer Maria Ehrhardt , Hörmedia Audioverlag, 2005, ISBN 3-938478-66-7 .

- The castle , told by Monica Bleibtreu , Anna Thalbach , Uwe Friedrichsen and others, Verlag Patmos, Düsseldorf 2006.

- The trial , told by Alexander Khuon , Mathieu Carrière and Anja Niederfahrenhorst, Verlag Patmos, Düsseldorf 2007

- The judgment. A story and other stories, read by Axel Grube, 1 CD, running time 66 min., Onomato Verlag, Düsseldorf 2008, ISBN 978-3-939511-56-4 .

- Diaries 4–12 from 1912–1923, read by Axel Grube, 1 CD, running time 73 minutes, onomato Verlag, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-933691-04-4 .

- Stories, read by Axel Grube, 1 CD, running time 79 minutes, onomato Verlag, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-933691-24-9 .

- Letter to the father , read by Till Firit , Mono Verlag , Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-902727-91-6

- Letter to the father, read by Stefan Fleming, 2 CDs, running time 134 min., Preiser Records, Vienna 2001, German Record Critics' Award

- A report for an academy , read by Hans-Jörg Große, running time 25 minutes, in-house production by Hans-Jörg Große and Christian Mantey, Berlin 2010.

- Gert Westphal reads Kafka - Stories and Reflections , 1 CD, Litraton, 2000, ISBN 3-89469-873-X .

- Gert Westphal reads Franz Kafka The Process , 7 audio cassettes, Litraton, September 2000, ISBN 3-89469-120-4 .

Audiobook collections

Letters

Kafka wrote letters intensely and, over a long period of his life, some very personal. They prove his high sensitivity and convey his view of the threatening aspects of his inner world and his fears in the face of the outside world. Some authors do not consider Kafka's letters to complement his literary work, but see them as part of it. His letters to Felice and letters to Milena in particular are among the great letters of the 20th century. The letters to Ottla are moving evidence of Kafka's closeness to his favorite sister (probably murdered by the National Socialists in 1943). In the letter to the father , the precarious relationship between the gifted son and his father becomes clear, whom he describes as a vigorous despot who is extremely critical of the son's conduct of life. The letters to Max Brod are documents of a friendship, without which only fragments of Kafka's work would have survived. With a few exceptions, the respective letters of reply have not been preserved, which is particularly regrettable in view of the missing letters from the journalist and writer Milena Jesenská, who for Kafka was the admired example of a free person without fear. Letters to Ernst Weiß, Julie Wohryzek and Dora Diamant have been lost to this day due to the circumstances of the time of National Socialism .

Editions of the letters

- Part of: Critical Edition. Writings, diaries, letters. Verlag S. Fischer, 1982 ff.

- Letters, Volume 1 (1900-1912). Published by Hans-Gerd Koch. Text, commentary and apparatus in one volume. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-10-038157-2 .

- Letters, Volume 2 (1913 to March 1914). Published by Hans-Gerd Koch. Text, commentary and apparatus in one volume. S. Fischer Verlag, 2001, ISBN 978-3-10-038158-3 .

- Letters, Volume 3 (1914-1917). Published by Hans-Gerd Koch. Text, commentary and apparatus in one volume. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-10-038161-3 .

- Letters, Volume 4 (1918-1920). Published by Hans-Gerd Koch. Text, commentary and apparatus in one volume. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, announced for July 2013, ISBN 978-3-10-038162-0 .

- Other editions:

- Malcolm Pasley (ed.): Franz Kafka, Max Brod - A friendship. Correspondence. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-10-008306-7 .

- Josef Čermák, Martin Svatoš (eds.): Franz Kafka - letters to the parents from the years 1922–1924. Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11323-7 .

- Jürgen Born, Erich Heller (ed.): Franz Kafka - letters to Felice and other correspondence from the engagement time. Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 3-596-21697-4 .

- Jürgen Born, Michael Müller (ed.): Franz Kafka - letters to Milena. Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-596-25307-1 .

- Hartmut Binder, Klaus Wagenbach (ed.): Franz Kafka - letters to Ottla and the family. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1974, ISBN 3-10-038115-7 .

Diaries

Kafka's diaries have largely been preserved for the period from 1909 to 1923 (shortly before his death in 1924). They contain not only personal notes, autobiographical reflections, elements of the writer's self-understanding about his writing, but also aphorisms (see e.g. Die Zürauer Aphorismen ), drafts for stories and numerous literary fragments.

Editions of the diaries

- Part of: Collected works in individual volumes in the version of the manuscript. Verlag S. Fischer, 1983.

- Hans-Gerd Koch (Ed.): Diaries Volume 1: 1909–1912 in the version of the manuscript. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994.

- Hans-Gerd Koch (Ed.): Diaries Volume 2: 1912–1914 in the version of the manuscript. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994.

- Hans-Gerd Koch (Ed.): Diaries Volume 3: 1914–1923 in the version of the manuscript. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994.

- Hans-Gerd Koch (Ed.): Travel diaries in the version of the manuscript. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994

- Part of: Historical-critical edition. Stroemfeld Verlag, 1995.

- Roland Reuß, Peter Staengle and others (eds.): Oxford Octave Books 1 & 2. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main and Basel 2004. (Period of creation of the Octave Books: late 1916 to early 1917)

- Roland Reuss, Peter Staengle and others (eds.): Oxford Quarthefte 1 & 2. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main and Basel 2001. (Period of the Quarthefte: 1910–1912)

Official writings

As an employee of the Workers' Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia, Franz Kafka wrote essays, reports, circulars and other things. See the “Working Life” section above.

Editions of the official publications

- Franz Kafka: Official writings. With an essay by Klaus Hermsdorf. Edited by Klaus Hermsdorf with the participation of Winfried Poßner and Jaromir Louzil. Akademie Verlag , Berlin 1984.

- Klaus Hermsdorf: Commendable administrative committee. Official writings. Luchterhand, 1991, ISBN 3-630-61971-1 .

- Klaus Hermsdorf, Benno Wagner (ed.): Franz Kafka. Official writings. S. Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 2004, ISBN 3-10-038183-1 . (Part of the Critical Kafka Edition. Translation of Czech texts and text passages and authorship of the text part of the explanations of the Czech versions of the annual reports of the Prague AUVA )

drawings

Editions of the drawings

- Niels Bokhove, Marijke van Dorst (Ed.): Once a great draftsman. Franz Kafka as a visual artist. Vitalis , Prague 2006, ISBN 3-89919-094-7 . - Also English edition: Niels Bokhove, Marijke van Dorst (eds.): A Great Artist One Day. Franz Kafka as a Pictorial Artist. Vitalis , Prague 2007, ISBN 978-80-7253-236-0 .

Poems

Editions of the poems

- Marijke van Dorst (Ed.): "Ik ken de inhoud niet ..." Poems / "I don't know the content ..." Poetry. Bilingual edition. Dutch translation: Stefaan van den Bremt. Explanations: Niels Bokhove. Exponent, Bedum 2000.

Settings

Since Kafka's texts became known to the public (see above “Reception”), composers have also been encouraged to set them to music. Kafka was rather reserved when it came to his personal attitude towards music. In his diary there is the remarkable message: “The essence of my lack of music is that I cannot enjoy music coherently, only here and there an effect arises in me and how rare is a musical one. The music I hear naturally draws a wall around me and my only lasting musical influence is that I am so locked up, different from being free. ”He once confided to his fiancé Felice Bauer:“ I have no musical memory at all. Out of desperation, my violin teacher preferred to let me jump over sticks during the music lesson, and the musical progress consisted in the fact that he held the sticks higher from hour to hour. "Max Brod, Kafka's close confidante," attested Although his childhood friend had 'a natural feeling for rhythm and melos' and dragged him into concerts, he soon gave up again. Kafka's impressions are purely visual. It is typical that only an opera as colorful as 'Carmen' could inspire him ”.

Remarkably, little attention has been paid to the phenomenon of Kafka setting. It was not until 2018 that a broad collection of articles on the subject of "Franz Kafka and Music" began to be dealt with. In response to the question of what could excite composers about Kafka's texts so much that they convert the texts into musical compositions, Frieder von Ammon tries to answer with the key concept of “music opposition”. Using Kafka's text The Silence of the Sirens , he shows that the literary model per se “does not have the desire” to “become music.” Although the text is by no means “unmusical”, it poses a special challenge for the composer when he forced the composers to “rigorously examine” the “compositional means to be used, and precisely at this moment, in the specific rebelliousness of Kafka's texts, in their anti-culinary, anti-operatic attitude, which is also a critical one Makes self-reflection necessary, there must be a special fascination for composers. There is no other explanation for the large number of Kafka compositions ”.

“Apparently Max Brod was the first to set a Kafka text to music; he himself reports that in 1911 he added a simple melody to the poem Kleine Seele - jumps im Tanze [...], "writes Ulrich Müller in a description of the settings of Kafka'scher texts (1979). Apart from this early work by Brod, his songs are Death and Paradise for song and piano (1952) and the song Schöpferisch schreite! from the song cycle op. 37 (1956) artistic evidence of his personal bond with the poet. - The 5 songs for voice and piano that were written in exile "in the years 1937/1938 under the impression of persecution by the National Socialists" are of historical importance, based on the words of Franz Kafka by Ernst Krenek , who in his music was "of existential oppression and threat of the individual ”and thus“ his own situation as an exile and persecuted ”. - Also in exile, Theodor W. Adorno's Six Bagatelles for voice and piano op. 6 (1942), including Trabe, little horse after Franz Kafka. With compositional means he traces Kafka's premonitions of war as well as the breakdown of familiar ways of life and old values, which Kafka put into words: “Little horse, you carry me into the desert, cities sink, […] girls' faces sink, carried away by the storm East. "

In the aforementioned account of the settings, Ulrich Müller notes that “Kafka's great impact on music only began in the early 1950s”. Important settings were created primarily in Eastern Europe, where the existential threat to the individual, characteristic of Kafka's work, was still perceptible in the reality of the composers' lives. “Perhaps the most famous setting is not based on Kafka's novels, but rather on his letters and diaries. The Hungarian György Kurtág jotted down individual sentences in his sketchbook over the years. 'Your world of short language formulas, filled with sadness, despair and humor, deeper meaning and so much at the same time, never let me go,' he once said. From this a cycle of 40 'Kafka fragments' for soprano and violin gradually developed in the 1980s. 'My prison cell - my fortress' was originally intended to be called, because it should also be understood autobiographically. The result is a work of extreme expressiveness and haunting brevity. ”In doing so, Kurtág uses a musical method of representation that corresponds to Kafka's typical language treatment: It is the“ reduction ”to small gestures and formulations that Klaus Ramm has attached to Kafka's work as a narrative principle . Several CD recordings prove the high degree of appreciation that Kurtág's Kafka fragments found in a very short time. The following is a list of Kafka settings made after the Second World War (in chronological order). The works are sorted by genre:

Stage works (opera, ballet, etc.)

- Gottfried von Eine : The Trial , Opera (1953).

- Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry : incidental music for the stage version (Kassel) of Das Schloss (1955).

- Rainer Kunad : The Castle Opera (1960/61).

- Roman Haubenstock-Ramati : Amerika , Oper (1961–64; new version 1992 under Beat Furrer ; 1967 four parts from it arranged as symphony “K” ).

- Niels Viggo Bentzon : Faust 3 , opera; Libretto uses themes and characters from Goethe, Kafka and Joyce (1964).

- Gunther Schuller : The Visitation , "Jazz opera freely based on a motif by Kafka" (1966).

- Joanna Bruzdowicz : The Penal Colony ; Opera for a single voice (bass), pantomimes, percussion and electronics (1968).

- Fiorenzo Carpi: La porta divisoria [The dividing door], opera (after Kafka The Metamorphosis ) 1969.

- Miloš Štědroň : Aparát , chamber opera based on: “In a Penal Colony” by Franz Kafka (1970).

- Ellis Kohs: America ; Opera (1971).

- Alfred Koerppen : The city arms ; Scene for solos (ten., Bar., Bass), mixed choir and large orchestra based on a text by Franz Kafka (1973).

- Peter Michael Hamel : Kafka-Weiss-Dialoge - incidental music for the "New Process" by Peter Weiss , for viola and violoncello (1983).

- André Laporte : The Castle , Opera (1986); from it two orchestral suites (1984/87).

- Rolf Riehm : The Silence of the Sirens (1987) expanded to a music-theatrical composition for 4 singers, 2 speaking voices and orchestra (1994).

- Aribert Reimann : Das Schloss , opera based on Kafka's novel (1990/92).

- Ron Weidberg: The Metamorphosis , Opera for solo voices and Ka.Orch. (1996).

- Xaver Paul Thoma : Kafka , Ballet in 24 Pictures (1995/96).

- Philip Glass : In the Penal Colony [ In the Penal Colony ], opera (2000).

- Thomas Beimel : In der Strafkolonie, music for the stage version of the story of the same name by Franz Kafka, (2001).

- Georg Friedrich Haas : The beautiful wound opera after Franz Kafka, Edgar Allan Poe and others. (2003).

- Poul Ruders : Kafka's trial , one-act play with prelude (2005).

- Salvatore Sciarrino : La porta della legge [ Before the Law ], Opera (2009).

- Hans-Christian Hauser: The blow to the courtyard gate - a scenic musical collage of 17 short stories by Kafka (2013).

- Philip Glass : The Trial [ The process ], opera (2015).

- Peter Androsch : Gold Coast - mono-opera based on “A Report for an Academy” by Franz Kafka for a singer and instrumental ensemble (2018).

Concert works

Singing with instrumental accompaniment

- Vivian Fine: The Great Wall of China , four songs for voice, flute, cello and piano (1948).

- Max Brod : Tod und Paradies , two songs based on verses by Franz Kafka for soprano and piano (1951).

- Hermann Heiss : Expression K. - 13 songs after Kafka for voice and piano (1953).

- Lukas Foss : Time Cycle, 4 songs for soprano and orchestra based on texts by Wystan Hugh Auden , Alfred Edward Housman , Franz Kafka and Friedrich Nietzsche (1959–1960); Version for soprano, clar., Cello, celesta, beat. (1960).

- Eduard Steuermann : On the gallery , cantata (1963/64).

- Alberto Ginastera : Milena , Cantata for Soprano and Orch. Op. 37 (1970).

- Fritz Büchtger : The message , chants after Franz Kafka for baritone and orchestra (1970).

- Alexander Goehr : The law of the quadrille for low voice and piano (1979).

- Lee Goldstein: An Imperial Message (based on a text by Kafka) for soprano and chamber ensemble (1980).

- Ulrich Leyendecker : Lost in the Night for soprano and chamber orchestra (1981).

- György Kurtág : Kafka fragments , song cycle for soprano and violin op.24 (1985/86)

- Vojtěch Saudek : An excursion into the mountains for mezzo-soprano and 11 instruments (1986).

- Ruth Zechlin : Early Kafka texts for voice and five instruments (1990).

- Rolf Riehm : The Silence of the Sirens for soprano, tenor and orchestra (1987).

- Anatolijus Ṧenderovas: The deep fountain after Franz Kafka for voice and five instruments (1993).

- Pavol Ṧimai: Fragments from Kafka's diary for alto voice and string quartet (1993).

- Menachem Zur: Singing a Dog for mezzo-soprano and piano (1994).

- Ron Weidberg: Josefine, the singer or Das Volk der Mäuse for soprano, string quartet and piano (1994).

- Peter Graham (pseudonym; aka Jaroslav Stastny-Pokorny): Der Erste , chamber cantata based on texts by Franz Kafka (1997).

- Gabriel Iranyi : Two parables based on texts by Franz Kafka for mezzo-soprano and string quartet (2nd string quartet / 1998).

- Abel Ehrlich : Kristallnacht , cantata for choir and orchestra, texts: Franz Kafka and fragments from Nazi songs (1998).

- Juan María Solare : Night for baritone, clarinet, trumpet and guitar (2000).

- Hans-Jürgen von Bose : K. Project based on texts from various works by Kafka for countertenor and violoncello (2002).

- Hans-Jürgen von Bose : The excursion into the mountains for countertenor and piano based on texts by Franz Kafka (2005) and Kafka cycle for countertenor and cello, dedicated to Aribert Reimann on the occasion of his 70th birthday (2006).

- Isabel Mundry : Who? after fragments by Franz Kafka for soprano and piano (2004).

- Jan Müller-Wieland : Rotpeters Trinklied - after Franz Kafka's “A Report for an Academy” for baritone and piano (2004); A dream, what else - freely based on Kleist and Kafka for Orch. (2006).

- Christian Jost : The exploding head: fragment from “The judgment” by Franz Kafka for soprano and piano (2004).

- Charlotte Seither : Einlass und Wiederkehr, Eleven Fragments for soprano and piano freely based on Franz Kafka (2004); Minzmeissel - Three little pieces for voice and piano , texts: Franz Kafka, (2006).

- Stefan Heucke : The song from the deepest hell , cycle based on texts by Franz Kafka for mezzo-soprano and piano op. 26 (2006).

- Péter Eötvös : The Sirens Cycle for string quartet and coloratura soprano (2016).

- Evgeni Orkin : Kafka songs based on poems by Franz Kafka for voice and piano op.67 (2017).

Speaking voice (s) with instrumental accompaniment

- Jan Klusák : Four small voice exercises. On texts by Franz Kafka for speaking voice and eleven wind instruments (1960). In the years 1993–97 he wrote his chamber opera Zprava pro Akademii based on Kafka's report for an academy .

- Jiráčková Marta: The Truth About Sancho Panza , based on an aphorism by Franz Kafka, for speaker, flute, bassoon, cello and percussion op. 48 (1993).

Choral music

- Ernst Krenek : 6 motets based on words by Franz Kafka, op.169 for mixed choir (1959).

- Zbyněk Vostřák : Cantata after Kafka for mixed choir, wind instruments and percussion op.34 (1964).

- Martin Smolka : The wish to become Kafka for mixed choir (2004).

Instrumental music (with content references to Franz Kafka)

- Boris Blacher Epitaph - In Memory of Franz Kafka (String Quartet No. 4) op. 41 (1951).

- Roman Haubenstock-Ramati : Assumptions about a dark house - Hommage à Franz Kafka , for Orch. (1963).

- František Chaun: Kafka trilogy for orchestra (1964–68).

- Armando Krieger: Metamorfosis d'après une lecture de Kafka for piano and chamber orchestra (1968).

- Petr Heym: Kafka Fragments for Piano (1971).

- Tomasz Sikorski : Abandoned looking out for piano (1971/72).

- Heinz Heckmann : Reflections for clarinet and violoncello on stories by Franz Kafka (1975).

- Friedhelm Döhl : Odradek for two open wings after Kafka (1976).

- Klaus-Karl Hübler: Chanson sans paroles - Kafka Study I for clarinet, violoncello and piano (1978).

- Frédérik van Rossum: Hommage à Kafka for percussion and piano (1979).

- Peter Michael Hamel : incidental music for The New Process ( Peter Weiss ) for viola and violoncello (1983).

- Francis Schwartz : Kafka in Río Piedras for orchestra (1983).

- Reinhard Febel : On the gallery , for 11 string instruments (1985).

- André Laporte : Castle Symphony (based on the novel by Kafka) for orchestra (1984/87).

- Tomasz Sikorski : Milczenie syren [The Silence of the Sirens] for cello solo (1987).

- Petr Eben : letters to Milena ; 5 piano pieces (1990).

- Ruth Zechlin : Music for Kafka , five movements for percussion solo based on early Kafka texts (1992); New version of the percussion pieces under the title Musik zu Kafka II (1994).

- Cristóbal Halffter : Odradek, Homenaje a Franz Kafka for large orchestra (1996).

- Friedemann Schmidt-Mechau : Dreierlei - music for baroque clarinet based on text fragments from reflections on sin, suffering, hope and the true path and from the third book of the octave by Franz Kafka (2002).

- Gianluca Podio : I giardini di Kafka , for guitar and marimba (2010).

Experimental forms of performance

- Hans Werner Henze : A country doctor. Radio opera based on a story by Franz Kafka (1951).

- Dieter Schnebel : The judgment - room music after Franz Kafka for instruments, voices and other sound sources (1959/90).

- Tzvi Avni : 5 Variations for Mr. K. for percussion and playback CD (1981).

- Juan María Solare : Little fable for speaking trio (2005).