Max Hodann

Max Julius Carl Alexander Hodann , nicknamed Hodenmaxe (born August 30, 1894 in Neisse , † December 17, 1946 in Stockholm ) was a German doctor , eugenicist , sex educator and publicist. He is one of the "pioneers of Marxist sex education".

life and work

Max Hodann was born into the family of the Silesian chief medical officer Carl Hodann. He went to school in Merano until 1903 and then switched to the humanistic grammar school in Berlin-Friedenau . From 1913 to 1919 he studied medicine at the University of Berlin - with an interruption from 1917 through military service during the First World War and subsequent participation in a workers 'and soldiers' council - and in 1919 was awarded a Dr. med. PhD . During his studies he was particularly interested in social hygiene ( Alfred Grotjahn ), anthropology ( Felix von Luschan ) and genetics ( Heinrich Poll ). In 1915 he also met the sexual reformer Magnus Hirschfeld , who had a major influence on his further development. Hodann became interested in left-wing politics through discussions in the house of Luise and Karl Kautsky , whom he had met through his friend Benedikt Kautsky .

Together with Jakob Feldner, he agitated against the militarization of youth in the Central Workplace for Youth Movement . About his involvement in the youth movement Hodann also came into contact with the socio-politically engaged Göttingen philosopher Leonard Nelson and was with his future wife Maria in 1917 co-founded the Nelson in the wake of the war with Minna Specht launched the International Youth League (Youth Library). First he was a brief member of the USPD and from 1922 the SPD . In the Jewish movement he also became an active supporter of the Association of Resolute School Reformers led by Paul Oestreich . After the SPD had passed an incompatibility resolution against the IJB in 1926 , there were strategic differences between Nelson and Hodann. Nelson transformed the IJB into a kind of left splinter party, the International Socialist Fighting League (ISK) , to which Hodann no longer wanted to belong. After he was excluded from the SPD as an IJB member, he later never joined a political party. In July 1926 he divorced his wife, the publicist Maria Hodann, née Saran (later Mary Saran ), whom he had married on December 24, 1919 and from whom he had been separated for several years, and married Gertrud (Traute) Neumann, the couple separated in 1934. He was the father of a daughter from his first marriage and a daughter from his second marriage. His third marriage was in 1944. The last marriage resulted in a son.

After completing his studies, Hodann initially worked as a senior physician in the venereal diseases department at the Berlin Dermatology Clinic for Ernst Kromayer . From 1921 to 1922 he was city doctor in Nowawes and from 1922 to 1933 city doctor and head of the health department in Berlin-Reinickendorf . In 1923 he was the founder of the first maternal advice center in Berlin.

At the same time, after his break with Nelson, he took over the vacant position at Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexology in 1926 as Hirschfeld's closest colleague, the psychiatrist Arthur Kronfeld (who was also a friend of Nelson) , opened his own practice. During this time, until 1929, Hodann headed the sex counseling center and the eugenics department for mother and child at the institute and organized public evenings for questions about sex education . He was involved in the Reich Association for Birth Control and Sexual Hygiene and in the Committee for Birth Control .

Hodann was also active in several other organizations, for example he was a member of the Medical Association from 1922 to 1933. In addition, he was on the board of directors of the Association of Socialist Doctors and took on leading positions in the Proletarian Health Service in 1923. In 1928 he became the first chairman of the Union of Friends of the Soviet Union and 1929/30 publisher of the magazine Freund der Sowjets . In Moscow he took part in the "Celebrations of the 10th Anniversary of the October Revolution ". From 1927 he was a member of the Reich Board of International Workers Aid , but was expelled from this organization in 1931 due to criticism of the Soviet Union. From 1932 he was a member of the leadership of the combat committee against the imperialist war .

In addition to the sexual reform , Hodann, like many of his time, saw eugenics as an urgent task. In 1924 he quoted the racial hygienist Heinrich Poll approvingly :

- “ Just as the organism relentlessly sacrifices degenerate cells [...] in order to save the whole: so should the higher organic units, the clan association, the state association, not shy away from interfering with personal freedom, the bearers of pathological genetic material to prevent harmful germs from being carried on through generations. "

Hodann added: “ Who is (today) seriously trying to eliminate germ damage? [...] it will not least be up to the socialist society to take eugenic measures to protect society from the burden of inferior offspring. "In this sense, Hodann spoke out in favor of a" reasonable "regulation of contraception, because otherwise it would be" necessarily connected with the loss of valuable genetic material, since of course the birth restriction occurs first in the most valuable families who shape their lives more responsibly than others. Such a loss of valuable genetic material is also worrying in the interests of the proletariat. "

Hodann's view of eugenics was widely accepted at the time, even among the political left, which often invited the “brilliant speaker” to lecture tours, mainly for a young audience. It was always about questions of practical life: for a sex-affirming upbringing, for responsible child witnessing, against alcohol abuse, against binge drinking , but above all against the prevailing repressive sexual morality , the latter consistently included anti-clerical statements. Hodann was popular throughout Germany and Austria, also because of his educational pamphlets. Following his example, other initiatives were organized, such as In Vienna, for example, Wilhelm Reich and Marie Frischauf founded the Socialist Society for Sexual Counseling and Sexual Research in 1928 . His publicity campaign for the removal of taboos on sexuality, birth control, abortions , decriminalization of homosexuality , anti-militarism and the Soviet Union met with violent opposition from conservative circles. His publications “Gender and Love” and “Klapperstorch” were censored and confiscated for immorality. In 1928, proceedings were brought against Hodann and his publisher for “violation of public morality”. The Nazi press also agitated violently against Hodann.

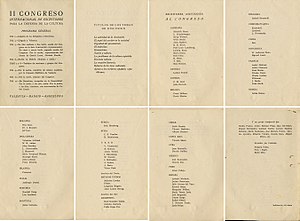

After the Reichstag fire at the end of February 1933, Hodann was arrested by the Gestapo in Berlin, taken into protective custody until June of that year and then released from office. After his release, he emigrated to Switzerland in November 1933 , from where he began to work internationally. First he toured Palestine and Syria in 1933/34 and wrote travel reports. After further stops in exile, Hodann first moved to England in 1935 , where he unsuccessfully tried to set up a sex research institute. Seriously ill with asthma , he gave up his plans to emigrate to the Soviet Union in 1936. He was expatriated from the National Socialist German Reich in 1935. In this context, the Nazi regime declared him to be the "proclaimer of false sexual doctrines [...] aimed at demoralizing the German people and especially the youth". His doctorate was revoked in 1937. In exile he lived under the most difficult economic conditions. As a military doctor in the International Brigades , he took part in the Spanish Civil War in 1937/38 .

In 1937 he published an article in the International Medical Bulletin , a journal of emigrated German doctors published from 1934 to 1939, on the release of the provocative abortion in Catalonia. In it he welcomed the law passed by the socialist government there in 1937 , which gave women the possibility of an abortion carried out in a clinic by a doctor and free of charge . He emphasized that in anti-fascist Spain equal rights for women were guaranteed, in contrast to Germany and Italy, where - despite assurances to the contrary - attempts were made to limit women's areas of life to “kitchen and children”.

After the defeat of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, he fled to Norway via France. Until the German occupation he stayed in Norway until spring 1940 and then in Sweden . As in Norway, he continued to educate people there, gave lectures and published articles in the magazine Sexual Frågan . Initially a staff member, he advised the British embassy on political issues from March 1944 to July 1945, and in this role he performed tasks as an intermediary for German emigrant organizations and looked after deserted soldiers. He also published the notices for military refugees and was the contact person for an orientation group of young Germans in Sweden . He was a founding member of the Free German Cultural Association (FDKB) in Sweden. Until November 1945 he took over the chairmanship of the FDKB, from which he, however, resigned after criticism from the organization of his advisory work for the British embassy in November 1945. He became a member of the coordinating committee for democratic development work (in Germany) and wrote another text, “The German Abroad Organizations on the German Question”. He died on December 17, 1946 of complications from his asthma.

Peter Weiss created a literary monument for Max Hodann in his novel Aesthetics of Resistance .

Fonts

(Selection; for a detailed bibliography see Wilfried Wolff: Max Hodann. (1894–1946). Socialist and Sexual Reformer (= series of publications of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft 9). Von Bockel, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-928770-17-9 , Pp. 268–279)

- Max Hodann and Walther Koch (eds.): The Urburschenschaft as a youth movement. In contemporary reports on the centenary of the Wartburg Festival . Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Jena 1917.

- The socio-hygienic importance of the counseling centers for sexually ill people , with special consideration of the counseling center of the State Insurance Institute Berlin (Med.Diss.). In: Archives for Social Hygiene, Volume 14, Issue 1, 1920 (special print)

- Parent and infant hygiene (eugenics): suggestions for educators . (= Decided school reform issue 6), Verlag Ernst Oldenburg, Leipzig 1923

- Boy and girl. Discussions among comrades about the gender issue. (= Decided school reform issue 25), Verlag Ernst Oldenburg, Leipzig 1924, 114 pp.

- Gender and love in biological and social relationships. Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1927, 272 pages (numerous new editions; English, French) and edition of the Gutenberg Book Guild , 2nd edition: Berlin 1932.

- Adult sexual distress. Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1928, 47 pp.

- Sexual misery and sex counseling. Letters from practice. Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1928, 302 pp.

- From the art of love affairs. Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1928, 16 pp.

- Sex education. Educational hygiene u. Health policy. Collected essays u. Lectures (1916-1927). Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1928, 256 pp.

- Fornication! Fornication! Mr. Public Prosecutor! On the natural history of German shame. Rudolstadt: Greifenverlag 1928, 131 pp.

- Masturbation - neither vice nor illness. Berlin: Universitas 1929, 91 pp.

- Does the rattle stork really bring us? A textbook that children can read. Berlin: Universitas 1930, 47 p. With seven printed drawings by the author

- Soviet Union yesterday - today - tomorrow. Berlin: Universitas 1930, 264 pp.

- The Slavic belt around Germany. Poland, Czechoslovakia and the German East Problems. Berlin: Universitas 1932, 319 pp.

- History of Modern Morals. (Translation by Stella Brown) London: Heinemann 1937, 340 pp.

Journal articles (selection)

- In: The Socialist Doctor

- The problem of sex education. Volume II (1926), Issue 1 (April), pp. 22-24 digitized

- Critical to » Gesolei «. Volume II (1926), Issue 2-3 (November), pp. 2-5 digitized

- Guidelines for practicing so-called marriage counseling. Volume III (1927), Issue 4 (March), pp. 12-16 digitized

- Answer to: On the reform of medical studies. A survey. Volume III (1927), Issue 4 (March), p. 33 digitized

- The fight of the German authorities against medical education. Volume III (1928), Issue 4 (April), pp. 5-10 digitized

- (Explanation) Board election. Volume V (1929), Issue 1 (March), p. 45 digitized

- News about abortion? Volume VI (1930), Issue 4 (October), pp. 157-161 digitized

- Explanation. Volume VI (1930), Issue 4 (October), p. 189 digitized

- Struggle for health security in Soviet Russia. Volume VII (1931), Issue 3 (March), pp. 80-84 digitized

- Some remarks on the seloprocess. Volume VII (1931), Issue 11 (November), p. 305 digitized

- In: International Medical Bulletin

literature

- Friedrich Koch : S exual pedagogy and political education. List, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-471-66577-3 .

- Manfred Herzer : Max Hodann and Magnus Hirschfeld: Sex Education at the Institute for Sexology. In: Communications from the Magnus Hirschfeld Society. Issue 5, March 1985, ISSN 0933-5811 , pp. 5–17 (repr. In: R. Dose and H.-G. Klein (eds.): Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft. Volume I: Issue 1 ( 1983) - Issue 9 (1986). Von Bockel Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-928770-06-3 , pp. 159-171).

- Hans-Joachim Bergmann: "Germany is a republic that is governed from Rudolstadt." The criminal proceedings against Max Hodann and Karl Dietz in Rudolstadt in 1928 - at the same time a contribution to the history of Greifenverlag. In: Marginalia. H. 117, 1990, ISSN 0025-2948 , pp. 35-43.

- Wilfried Wolff : Max Hodann. (1894-1946). Socialist and sexual reformer (= series of publications by the Magnus Hirschfeld Society 9). von Bockel, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-928770-17-9 .

- Ralf Dose : No Sex Please, We're British, or: Max Hodann in England in 1935 - a German emigrant looking for an existence. In: Communications from the Magnus Hirschfeld Society. Issue 22/23, June 1996, pp. 99-125.

- Bernhard Meyer, Hans Jürgen Mende (ed.): Berlin Jewish doctors in the Weimar Republic. Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-89626-073-1 (note: Hodann was not a Jew).

- Werner Röder, Herbert A. Strauss (Ed.): Biographical Handbook of German-Speaking Emigration after 1933. Vol. 1: Politics, Economy, Public Life , Saur, Munich, 1999 (= 1980), ISBN 3-598-10087-6 , P. 304.

- Rudolf Vierhaus (Ed.): German Biographical Encyclopedia . Volume 5: Hitz – Kozub. 2nd edition, Saur, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-598-25035-4 , p. 12.

- Günter Grau: Max Hodann (1894–1946) . In: Volkmar Sigusch and Günter Grau (eds.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-39049-9 , pp. 296-302.

Web links

- Literature by and about Max Hodann in the catalog of the German National Library

- On Hodann's role at Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexology ; Picture separately

Individual evidence

- ^ Günter Grau: Max Hodann (1894–1946) . In: Volkmar Sigusch and Günter Grau (eds.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, p. 296

- ↑ a b c d e Biographical Handbook of German-speaking Emigration after 1933 , Volume 1: Politics, Economy, Public Life , Munich 1980, p. 304

- ↑ a b c d e Günter Grau: Max Hodann (1894–1946) . In: Volkmar Sigusch and Günter Grau (eds.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, p. 297

- ↑ a b c d Alfons Labisch / Florian Tennstedt: The way to the "Law on the Unification of the Health System" of July 3, 1934. Development lines and moments of the state and municipal health system in Germany , Part 2, Academy for Public Health in Düsseldorf 1985 , P. 430f.

- ↑ Kulenkampff'sche Familienstiftung (ed.), Family tables of the Kulenkampff family, Bremen: Verlag BC Heye & Co 1959, line John Daniel Meier, JDM, pp. 47–50.

- ^ A b c d Matthias Heeke: Journeys to the Soviets. Foreign tourism in Russia 1921–1941. With a bio-bibliographical appendix to 96 German travel authors , Lit Verlag, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-8258-5692-5 , p. 584.

- ↑ Kathleen M. Paerle and Stephan Leibfried (eds.). Kate Frankenthal . The triple curse: Jewish, intellectual, socialist. Memoirs of a doctor in Germany and in exile , Campus, Frankfurt / NY 1981, ISBN 3-593-32845-3 , p. 290

- ↑ Max Hodann: What do our comrades need to know about eugenics? In: The Socialist Education (Vienna), May 1924; reprinted in ders .: Sexualpädagogik. Educational Hygiene and Health Policy. Collected essays and lectures 1916-1927. Greifenverlag, Rudolstadt 1928, pp. 66–73; for details and context cf. Wilfried Wolff: Max Hodann. (1894-1946). Socialist and sexual reformer (= series of publications by the Magnus Hirschfeld Society 9). von Bockel, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-928770-17-9 , pp. 203-223.

- ↑ Karl Fallend: Max Hodann "Hodenmaxe" . In: ders .: Wilhelm Reich in Vienna. Psychoanalysis and politics. Geyer Edition, Salzburg 1988, pp. 85-93.

- ^ A b c Günter Grau: Max Hodann (1894-1946) . In: Volkmar Sigusch and Günter Grau (eds.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, p. 298

- ↑ "International Medical Bulletin". 4 (1937) Issue 6-7 (July-August), pp. 70-73 Max Hodann-Valencia. The release of the provocate abortion in Catalonia. Digitized

- ^ A b Günter Grau: Max Hodann (1894–1946) . In: Volkmar Sigusch and Günter Grau (eds.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, p. 299

- ^ Previously, Weiss had Hodann appear in his novel Vanishing Point under the name Hoderer. Hodann had been Weiss's teacher in his Berlin youth; later they were together in exile in Sweden (cf. Karen Hvidtfeldt Madsen: Resistance as Aesthetics: Peter Weiss and "The Aesthetics of Resistance". Wiesbaden 2003, p. 79) Weiss only met Hodann in Stockholm in 1940; the contacts in Berlin described in the novel The Aesthetics of Resistance are fiction.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hodann, Max |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hodann, Max Julius Carl Alexander |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German doctor, sex reformer, eugenicist and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 30, 1894 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Neisse |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 17, 1946 |

| Place of death | Stockholm |