Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (born May 14, 1868 in Kolberg , † May 14, 1935 in Nice , France ) was a German doctor , sexologist and co-founder of the first homosexual movement.

Life

Early years

Magnus Hirschfeld came from a Jewish family and was the son of the Kolberg doctor Hermann Hirschfeld (1825–1885), who was appointed to the medical council for his services in the medical service during the Franco-German War .

For the winter semester of 1887/1888 Magnus Hirschfeld first studied linguistics (philology) in Breslau , then medicine in Strasbourg , Munich , Heidelberg and Berlin , where he received his doctorate in medicine in 1892. In Heidelberg he was a co-founder of Badenia Heidelberg , which, as a free and powerful association, was one of the founding associations of the Kartell-Conventes of the associations of German students of the Jewish faith in 1896 . He then opened a naturopathic and general medical practice in Magdeburg ; two years later he moved to the then still independent Charlottenburg near Berlin.

On May 15, 1897, he founded the Scientific and Humanitarian Committee (WhK) with the publisher Max Spohr , the lawyer Eduard Oberg and the writer Franz Joseph von Bülow in his Charlottenburg apartment at Berliner Straße 104 (today Otto-Suhr-Allee ), he was elected chairman. The committee was the world's first organization that set itself the goal of decriminalizing sexual acts between men. A petition to the Reichstag to delete the infamous paragraph 175 from the penal code was negotiated there, but failed.

From 1899 to 1923 Hirschfeld published 23 volumes of the journal Jahrbuch für Sexuelle Zwischenstufen .

From 1903/04 he conducted statistical surveys on sexual orientation among students and metalworkers for his investigations, resulting in a population share of 2.3% homosexuals and 3.4% bisexuals . After some of the students interviewed reported him, he was convicted of insult on May 7, 1904. In its meeting on January 22, 1904, the Munich branch of the WhK criticized Hirschfeld's approach to the student survey and distanced itself from Hirschfeld on account of the criminal charges in the meeting of April 22, 1904.

In 1908 he founded the Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft , whose publication he had to stop again in the same year. The journal, which was first entitled Sexualwissenschaft , was published by Georg H. Wigand, Leipzig. Friedrich Salomon Krauss provided editorial support .

In the years 1907 to 1909, Hirschfeld's controversial activity as a court expert for sexual questions in the context of the Harden-Eulenburg affair received special public attention ; Hirschfeld also testified as an expert in the Mattonet murder case , which involved blackmailing and the death of a homosexual. The couplet poet Otto Reutter caricatured the expert's analytical approach and the homophobia rampant in the aristocracy and officer corps in 1908 in his Hirschfeldlied , which was already widely used on records and which also increased Hirschfeld's popularity. It is the first vinyl recording that is directly related to homosexuality.

In 1910, Hirschfeld published his important research work The Transvestites: An investigation into the erotic disguise instinct , and thus coined the term transvestite for people who wear clothes of the opposite sex .

1914-1933

During the First World War , Hirschfeld worked, among other things, as a doctor for prisoners of war on behalf of the Red Cross. During this time he wrote his most important sexological work, the three-volume Sexualpathologie (published 1917–1920).

In 1918 he set up the Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation , the basis for another pioneering achievement of his, the establishment and equipment of the world's first institution for sex research - his Institute for Sexology . Hirschfeld was able to open it on July 6, 1919 with the dermatologist Friedrich Wertheim and the versatile neurologist and psychotherapist Arthur Kronfeld , who gave the scientific opening lecture.

In the same year Hirschfeld was a consultant and contributor in the first gay film in film history, Anders als die Andern by Richard Oswald . In it, he more or less played himself as a doctor conveying that homosexuality is not a disease.

In 1921 the institute organized the “First International Conference for Sexual Reform on the Basis of Sexology”, attended by well-known sexologists who were left-liberal and opposed a patronizing state on questions of morality. They shared the conviction that sexology would create the basis for social reform. Hirschfeld was also a member of the management of Adolf Koch's Institute for Naturism, which was founded around 1923 .

At the second congress, which took place in Copenhagen in 1928, the " World League for Sexual Reform " was founded, which counted the Berlin congress as its first and held further congresses in London (1929), Vienna (1930) and Brno (1932). The central office was located in the Institute for Sexology. In 1935 the World League for Sexual Reform was disbanded; only the English section continued to work. In addition to Magnus Hirschfeld, the Swiss psychiatrist Auguste Forel and the Austrian sociologist and honorary president of the Monist Association, Rudolf Goldscheid, were also involved in the world league from German-speaking countries . Magnus Hirschfeld also represented eugenic ideas and was a member of the Society for Racial Hygiene .

In 1920, after a lecture in Munich, Hirschfeld was seriously injured by "völkisch hooligans"; Newspapers even reported his death and he could read his own obituaries. He later remained the target of National Socialist smear campaigns, especially in Stürmer , and his lectures were increasingly disturbed by thugs. In 1926 he traveled to Moscow and Leningrad at the invitation of the government of the USSR. He remained a particular enemy of the National Socialists, although some were even his patients, and as early as 1930 could no longer feel safe about his life. In 1931 he accepted an invitation to give lectures in the United States and then traveled with great honor through North America , Asia and the Orient.

From 1932

Because of warnings, he never set foot on German soil, but remained in exile, first in Zurich and Ascona in Switzerland, then in Paris and Nice.

In 1933 the National Socialists ordered the closure of the Institute for Sexology , and on May 6, 1933, the institute was plundered and destroyed by students of the German University for Physical Education , officials and members of the Nazi organization German Student Union . The institute library ended up with a bust of Magnus Hirschfeld in the fire of the book burning on Berlin's Opernplatz, today's Bebelplatz . Ludwig Levy-Lenz , a doctor who practiced at the Institute for Sexology until 1932, assumed that the reason for the destruction of the institute was that many National Socialists were being treated there and that the institute's records contained things that could have been harmful to the National Socialist leadership . No evidence has yet been found for these assumptions. Hirschfeld's publications were listed in a guideline for the “cleaning up” of libraries as examples of “popular and racial” writings to be removed.

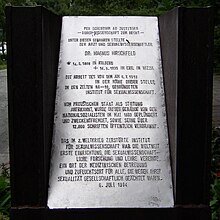

In Paris, Hirschfeld's attempt to found a new institute ( Institut des sciences sexologiques ) with the doctor Edmond Zammert failed . In 1934 he moved to Nice, where he died on his 67th birthday in 1935. His motto for life is written on his grave stone in Nice: “ per scientiam ad iustitiam ” (Latin for “through science to justice”).

Hirschfeld was well known and was called "Aunt Magnesia" in the famous " Eldorado " bar , which was frequented by many transvestites and in which 'lady imitators' also performed. After his death, there were unsubstantiated rumors that he was a transvestite himself.

Between 1933 and 1934, Hirschfeld wrote an analysis and refutation of the National Socialist racial doctrine, which was published posthumously in 1938 in English translation under the title Racism . This work is one of the first to use the term racism . Racism serves as a safety valve against a national feeling of disaster and seems to ensure the restoration of self-respect, especially since it is directed against an easily accessible and not very dangerous enemy in one's own country and not against a respectable enemy beyond national borders. Hirschfeld was unable to gain anything from the concept of “race” that was of scientific value; instead, he recommended the deletion of the expression "as far as subdivisions of the human species are meant".

Late personal life and inheritance

In the early 1920s, Hirschfeld met Karl Giese at a lecture , who has lived with him ever since and worked in the archive of Hirschfeld's institute. In 1931 he met his second lover in Shanghai, the 23-year-old medical student Tao Li (born 1907), whose real name was Li Shiu Tong .

Until his death, Hirschfeld lived with his two lovers in a ménage à trois in Switzerland and France. Two months earlier he had made both of them his sole heirs, with the express stipulation that their portion of the inheritance should not be used for personal use but only for the purposes of sexology. Karl Giese was awarded the library and those items that had been "saved from Germany" from the institute with his help. Karl Giese committed suicide in Brno in March 1938 . His heir, the lawyer Karl Fein, was deported and murdered by the Nazi regime in 1942. Since then, his property and the Hirschfeld legacy have been lost.

Li Shiu Tong, who had supported Hirschfeld with his fortune in exile, received securities, books and personal notes from Hirschfeld. Li died in Vancouver on October 5, 1993.

Part of his inheritance, including a diary-like “will” from 1929 to 1935, came into the possession of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society in 2003 . Another part is owned by Li’s heirs.

In 2010, another part of personal documents (e.g. letters) was discovered: A great-nephew of Hirschfeld, Ernst Maass (1914–1975), who had taken care of his burial, had taken them. In 2011, his son Robert from New York City also left an extensive part of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society.

meaning

As one of the decisive pioneers of the sexology emerging in Europe and North America at the end of the 19th century , Hirschfeld already outlined in his first sexological publication Sappho and Sokrates or How is the love of men and women for persons of their own sex explained? (1896) made his most important contribution to the new science: the doctrine of the sexual intermediate stages. It meant a transformation of the universally accepted binary gender order to a radically individualized view: All men and women are therefore unique, unrepeatable mixtures of male and female characteristics. This intermediate level theory served Hirschfeld as the basis of his sexual policy, which aimed at the emancipation of sexual minorities from state persecution and social ostracism, "the full realization of sexual human rights" worldwide.

Fields of activity

Theory of the "third gender" and the theory of the "intermediate stages"

In 1904, Benedict Friedlaender put forward the thesis that Hirschfeld had continued Karl Heinrich Ulrichs ' Urning theory with his interim teaching. It was picked up by Sigmund Freud in various polemics against Hirschfeld and imported into today's queer theory via Jim Steakley .

In fact, Hirschfeld further elaborated Ulrich's thesis of a “third gender”, which was backed up with scientific data on embryonic development towards the end of the 19th century, using newer research methods. In his book Gender Transitions (1905) he tried to establish regularities for the frequency of gender "deviations". It was not until 1910 that he took over the term “intermediate level theory” from the reception of his research. However, he did not regard it as a theory, but as a "classification principle". Hirschfeld wrote in 1914: "By sexual intermediate stages we mean men with female and women with male influences." "Intermediate stages" of women and men, which he attached to the physical characteristics, character and desires of a person, are for Hirschfeld innate and unchangeable, mixed sexes Types, of which he identified 81 basic types, are the rule. According to this, homosexuality lies within an expanded spectrum of normality. He popularized the theory of homosexuals as a "third gender" with educational pamphlets and in lectures and used them in the fight against § 175 .

Although traditional notions of the essence of ideal masculinity and ideal femininity were the reference values for the intermediate types, Hirschfeld rejected anti-feminist tendencies within the homosexual emancipation that gathered around the magazine Der Eigen , founded by Adolf Brand in 1896 . This made selective cooperation between the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and the women's movement possible, especially its bourgeois-radical wing, such as the voting rights movement around Helene Stöcker , Anita Augspurg and others

Hirschfeld's theory of the intermediate stages was falsely reduced to a theory of homosexuality in the reception. Rather, it can be read as a “plea for the diversity of people”. (Seeck, Dannecker) It aims to depathologize physical or psychological characteristics that deviate from social gender norms.

In 2011 Manfred Herzer attempted to interpret the intermediate level theory as an ideological expression of the development of individuality in the capitalist social formation.

Eugenics

In an essay from 1983 Volkmar Sigusch problematized the role of Forel and Hirschfeld in eugenic Nazi politics. The criticism led to a controversial discussion and a closer examination of Hirschfeld's writings. Sigusch wrote in an essay from 1995 that Hirschfeld was not a pioneer of eugenics and certainly not a “spiritual forerunner of fascism”. It is about, writes Sigusch, "that the philanthropist Hirschfeld [...] who was an opponent of National Socialism, was theoretically not prepared, together with other sexological eugenicists, to critically reflect on the discourse that the Nazis took up and used thus "spiritually" to contradict ".

Hirschfeld popularized the connection between sexology and eugenics , a view adopted by sexual reformers such as Iwan Bloch , Auguste Forel and others. a. was shared. He used a common usage of the time that is reminiscent of Nazi jargon today. In 1913, the Society for Sexual Sciences added to her name and eugenics . It was considered sensible and progressive to use the knowledge gained from biology to regulate reproduction in order to avoid "degeneration". Hirschfeld wanted to achieve this through education, prevention and legalization of abortion on a voluntary basis, not through coercive measures, as he was falsely accused of. He considered forced castration to be useful in certain situations, such as serious sexual crimes. Forced sterilization should be allowed as a eugenic preventive measure for people who are “so mentally stupid that they are unable to control themselves”. He categorically rejected euthanasia of Nazi racial hygiene based on eugenics . When the National Socialist Act for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseases was passed in 1934 , Hirschfeld was in exile. He stuck to the vision of “raising people up” aimed at by eugenics, but pointed to the in a series of articles (including: Phantom Race. A pipe dream as a world danger ) in the pacifist Prague magazine Die Truth 1934/35 Dangers of "abuse" by the National Socialists. Hirschfeld never linked his eugenic vision with racism . In his five-volume work Gender Studies (1926–1930) he had already criticized the rampant “enthusiasm for racial purity”. In the posthumously published collection of essays Racism he proclaimed the benefits of opposition to the Nazi ideology miscegenation .

Martin Dannecker's criticism (1983) that Hirschfeld's theory of intermediate stages fed the eugenic “delusion” is rejected by Heinz-Jürgen Voss (2014) as a “twisting of history”. Rather, the Black Corps had opposed the sexual-biological explanatory model of homosexuality on which Ulrichs and Hirschfeld were based and emphasized that homosexuality was acquired and that it was a matter of "liberating" people from it through educational means. (See also: Homosexuality in Germany # Time of National Socialism )

Post fame

In the SchwuZ in Berlin, founded in 1977 , one room was called the Tante Magnesia Room . Even after two moves there is still a room with this name.

- Magnus Hirschfeld Society

In 1982 the Magnus Hirschfeld Society was founded in West Berlin by a small group of gays and lesbians with a strong historical interest. The initiative arose from efforts to ensure that the homosexual victim group would not be left out at the upcoming events for the 50th anniversary of the seizure of power in 1933. Furthermore, an institute for sexology was to be set up again in order to deal critically with Hirschfeld's work, which also dealt with contraception, sterilization, the fight against venereal diseases or population policy. Over time, other historical topics were also addressed.

The Magnus-Hirschfeld-Centrum (mhc) opened in Hamburg in 1983 as a center for advice, communication, culture and youth and is now one of several institutions in the city's gay and lesbian scene.

A gay magazine published from 1989 to 1996 was called magnus .

Since 1990, the German Society for Social Science Sex Research has awarded the Magnus Hirschfeld Medal for special merits in sex science and sexual reform.

- Magnus Hirschfeld Archive

In 1994 Erwin J. Haeberle founded the Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin , which has been run at the Humboldt University since 2001.

- Film about Hirschfeld

His life was filmed in 1999 by Rosa von Praunheim under the title Der Einstein des Sex . In 1930 Viereck's book “Schlagschatten” was published by Eigenbrödler Verlag (Berlin / Zurich). 26 fateful questions for greats of this time ”. It contains interviews with GB Shaw, G. Hauptmann, S. Freud, H. Ford, Paul v. Hindenburg, Hirschfeld and others. The Hirschfeld contribution is entitled: "Hirschfeld: the Einstein of the sex" (pp. 127–150).

- Hirschfeld Eddy Foundation

In honor of him and Fannyann Eddy , a Hirschfeld-Eddy Foundation established in June 2007 was named. This is to express that the struggle for the human rights of sexual minorities began in Europe, but is now taking place on all continents. The foundation wants to support human rights work internationally under the motto “No jail for love!”.

- Street names

At the initiative of the Lesbian and Gay Association , the promenade between the Moltke Bridge and the Chancellor's Garden was named Magnus-Hirschfeld-Ufer on May 6, 2008, diagonally across from the Federal Chancellery and in the vicinity of the former place of residence. Streets were named after him in other cities as well.

From May 7 to September 14, 2008, the Berlin Medical History Museum of the Charité presented an exhibition by the Magnus Hirschfeld Society with the title: Sex is burning. Magnus Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexology and Book Burning .

- Federal Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation

In 2011 the German federal government founded the Federal Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation , which aims to help reduce discrimination against homosexual and transgender people.

The second season of the Amazon television series Transparent includes a number of Hirschfeld appearances as Einstein of Sex , played by Bradley Whitford .

Honor

On the first day of issue on July 12, 2018, Deutsche Post AG issued a postage stamp with a face value of 70 euro cents to mark Magnus Hirschfeld's 150th birthday . The design comes from the graphic designer Andrea Voß-Acker.

Publications (selection)

- Sappho and Socrates. Verlag Max Spohr , Leipzig 1896 (under the pseudonym "Th. Ramien")

- Natural healing method and social democracy. In: Hausdoctor. Volume 8, 1897, pp. 249-251.

- Section 175 of the Reich Criminal Code : the homosexual question in the judgment of contemporaries . Spohr, Leipzig 1898 ( digitized version )

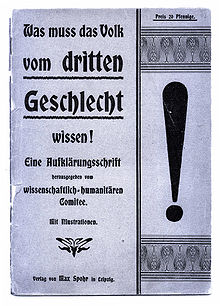

-

What must the people of the third sex know! Verlag Max Spohr, Leipzig 1901

easily understandable written educational pamphlet, which presents the aims of the Whk in a large edition and at a low price. - The urnian man. Max Spohr, Leipzig 1903 ( online in Google Book Search - USA )

-

Berlin's third gender . At H. Seemann, Berlin a. Leipzig 1904 - Reprint: Verlag Rosa Winkel, 1991, ISBN 3-921495-59-8

28th edition in 1908

French translation: Les homosexuels de Berlin. Le troisième sexe , Paris 1908

Russian translation: Третій полъ Берлина , St. Petersburg 1908 * Magnus Hirschfeld, Berlins Third Sex 1904 (for Project Gutenberg-DE ) - The throat of Berlin . H. Seemann, Berlin a. Leipzig 1905 - Edited new edition: worttransport.de Verlag, Berlin 2016. ISBN 978-3-944324-70-8

- Gender transitions. Leipzig: Publishing house of the monthly for urinary diseases and sexual hygiene, W. Malende, [1905]. 2nd edition: Verlag Max Spohr, Leipzig 1913

- Of the essence of love. At the same time a contribution to solving the question of bisexuality . Max Spohr publishing house, Leipzig 1906

- The transvestites: An investigation into the erotic disguise instinct, with extensive casuistic and historical material . Alfred Pulvermacher publishing house, Berlin 1910

- Natural laws of love: A commonly understood investigation of the impression of love, the urge to love and the expression of love . Publishing house "Truth" Ferdinand Spohr, Leipzig, 1914

- The homosexuality of men and women . Verlag Louis Marcus, Berlin 1914 ( online text in the Internet Archive )

- Why do the peoples hate us? A. Marcus & E. Weber, Bonn 1915

- War psychology . A. Marcus & E. Weber, Bonn 1916

-

Sexual pathology. A textbook for doctors and students . Bonn, 1917–1920

- Volume I: Sexual development disorders with special consideration of masturbation

- Volume II: Sexual Intermediate Levels. The male woman and the female man

- Volume III: Disorders in the metabolism with special consideration of impotence

- The nationalization of health care . Berlin, 1919

- From then to now: History of a homosexual movement 1897–1922 . Series of publications of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society No. 1, Verlag rosa Winkel, Berlin 1986 (reprint of a series of articles by Magnus Hirschfeld for the Berlin gay magazine Die Freund 1921/22)

- Sexuality and crime. Overview of crimes of sexual origin . Vienna, Berlin, Leipzig, New York 1924

- Paragraph 267 of the Official Draft of a General German Criminal Code "Fornication Between Men" - A memorandum addressed to the Reich Ministry of Justice , Julius Püttmann Publishing House, Stuttgart 1925

-

Gender studies based on thirty years of research and experience . Stuttgart 1926-1930

- Volume I: The Physical Basics

- Volume II: Consequences and Consequences

- Volume III: Outlook

- Volume IV: picture part

- Volume V: Register

- The moral history of the world war (2 volumes). Verlag für Sexualwissenschaft Schneider & Co., Leipzig / Vienna, 1930

- A sex researcher's world tour . Bözberg-Verlag, Brugg 1933 - New abridged edition: Eichborn, Frankfurt a. M. 2006 (= The Other Library , 254). ISBN 3-8218-4567-8

- Sex in Human Relationships . John Lane the Bodley Head, London 1935

- Racism . Victor Gollancz Ltd., London 1938

-

Gender aberrations . A study book - primarily for doctors, pastors and educators. Carl Stephenson Verlag, Flensburg, Second Edition 1977.

“Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24 were published by Hirschfeld in leave a form ready for printing. His students then took over the completion of the work as a humble memorial for their great teacher. "(Quoted from the foreword)

Obituaries

- Max Hodann . Magnus Hirschfeld in memory. In: Internationales Ärztliches Bulletin , 2nd year (1935), Issue 5–6 (May – June), pp. 73–76 digitized

literature

- Manfred Baumgardt , Ralf Dose , Manfred Herzer , Hans-Günter Klein , Ilse Kokula , Gesa Lindemann : Magnus Hirschfeld - life and work. Exhibition catalog. Rosa Winkel, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-921495-62-8 (= publication series of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society 3). 2nd extended edition, with an afterword by Ralf Dose: von Bockel, Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-928770-00-4 (= series of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft , Volume 6; exhibition in the State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin, from 1 August to September 7, 1985).

- Hans Bergemann, Ralf Dose , Marita Keilson-Lauritz (eds.): Magnus Hirschfeld's guest book in exile 1933-1935. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin / Leipzig 2019, ISBN 978-3-95565-338-5 .

- Ralf Dose: Magnus Hirschfeld as a doctor. In: Ulrich Gooßb, Herbert Geschwind (ed.): Homosexuality and health. Berlin 1989, pp. 75-98.

- Ralf Dose: Magnus Hirschfeld: German, Jew, Cosmopolitan (= Jewish miniatures. Volume 15). Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin / Teetz 2005, ISBN 3-933471-69-9 .

- Ralf Dose: In memoriam Li Shiu Tong (1907–1993). On the 10th anniversary of his death on October 5, 2003. In: Communications from the Magnus Hirschfeld Society. Issue 35/36, Berlin 2003, pp. 9-23.

- Ralf Dose (ed.): Testament. Issue 2 , Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-95565-007-0 .

- Ralf Dose: The spurned legacy. Magnus Hirschfeld's legacy to the Berlin University . Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2015. ISBN 978-3-95565-105-3 .

- Christian Helfer: Hirschfeld, Magnus. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , p. 226 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Rainer Herrn: Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935). In: Volkmar Sigusch , Günter Grau (Hrsg.): Personal Lexicon of Sexual Research. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-39049-9 , pp. 284-294.

- Manfred Herzer : Magnus Hirschfeld: Life and work of a Jewish, gay and socialist sexologist . 2nd Edition. MännerschwarmSkript-Verlag, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-935596-28-6 ( online ).

- Manfred Herzer: Magnus Hirschfeld and his time. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2017, ISBN 978-3-11-054769-6 .

- Magnus Hirschfeld: Autobiographical Sketch . In: Victor Robinson : Encyclopaedia sexualis. A Comprehensive Encyclopedia-Dictionary of the Sexual Sciences. Dingwall-Rock, New York 1936, pp. 317–321 (digitized version )

- Elke-Vera Kotowski , Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): The sexual reformer Magnus Hirschfeld. A life in the field of tension between science, politics and society. Be.Bra, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-937233-09-1 (= Sifria , Volume 8).

- Volkmar Sigusch : History of Sexology . Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, pp. 197-233 and 345-390, ISBN 978-3-593-38575-4

- Charlotte Wolff : Magnus Hirschfeld. A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology . Quartet Books, London / New York 1986 ISBN 0-7043-2569-1 .

- Hirschfeld, Magnus , in: Werner Röder; Herbert A. Strauss (Ed.): International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigrés 1933-1945 . Volume 2.1. Munich: Saur, 1983 ISBN 3-598-10089-2 , p. 519

Web links

- Literature by and about Magnus Hirschfeld in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Magnus Hirschfeld in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Magnus Hirschfeld in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Bibliography of Hirschfeld's works

- Entry on Magnus Hirschfeld in the online exhibition on his Institute for Sexology

- Federal Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation

- Magnus Hirschfeld Society V.

- Per scientiam ad justitiam : Magnus Hirschfeld

- Rüdiger Lautmann : With the flow - against the flow. Magnus Hirschfeld and the sexual culture after 1900

- Archive for Sexual Science - Online Library: Essays with a debate between J. Edgar Bauer and Manfred Herzer and other essays about Hirschfeld

- Norman Domeier: Magnus Hirschfeld . In: Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson (Eds.): 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War . Berlin 2016 doi : 10.15463 / ie1418.10887 .

- Heribert Prantl: The Einstein of Sex. For the 150th birthday of Magnus Hirschfeld Süddeutsche Zeitung , online version from May 6, 2018, accessed on May 13, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ POLIN Museum for the History of Polish Jews, Hermann Hirschfeld ( Memento from July 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ralf Dose: The Hirschfeld family from Kolberg. In: Kotowski / Schoeps (eds.): The sexual reformer Magnus Hirschfeld. Berlin 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Wilfried Witte: Hirschfeld, Magnus. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 602 f.

- ↑ Peter Kaupp: "There, where you burn books ...", in Studentenkurier 2/2008, p. 7

- ↑ Martin Benedikt Geuer: The history of homosexuality. myfreedom.de, as of January 19, 2006.

- ^ Volkmar Sigusch: History of Sexual Science. Campus, Frankfurt / New York 2008, p. 71 u. 101.

- ↑ Erwin in het Panhuis: Different from the others. Gays and lesbians in Cologne and the surrounding area 1895–1918. Edited by Center for Gay History. Hermann-Josef Emons-Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 978-3-89705-481-3 , pp. 151-164. ( PDF pp. 88-93)

- ↑ Ralf Jörg Raber: "We ... are how we are!" Homosexuality on record 1900–1936. In: Invertito - Yearbook for the History of Homosexualities , 5th year, 2003, ISBN 3-935596-25-1 , p. 43.

- ↑ Magnus Hirschfeld: Sexualpathologie Volume 1-3. Retrieved on February 20, 2018 (German).

- ^ A b Institute for Social Science (1919–1933) : An online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, page: Sexualreform und Sexualwissenschaft

- ^ German students parade in front of the Institute for Sexual Research prior to their raid on the building. The students occupied and pillaged the Institute, then confiscated the Institute's books and periodicals for burning. , United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ^ A b Günter Grau: Lexicon on the persecution of homosexuals 1933-1945 , Lit Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 9783825897857 , p. 160

- ^ Erwin J. Haeberle : Swastika, Pink Triangle, and Yellow Star: The Destruction of Sexology and the Persecution of Homosexuals in Nazi Germany. In: Journal of Sex Research. Volume 17, No. 3 (August 1981), pp. 270-287.

- ↑ On the current state of research cf. Manfred Herzer: Looting and robbery of the Institute for Sexology. In: Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung 2009, pp. 151–162.

- ↑ Die Bücherei 2: 6 (1935), p. 279

- ↑ Hirschfeld's grave is still located today on the Cimetière de Caucade, Carré 9, grave number 18.543. A photo of the grave and the site plan of the cemetery can be found on the website Kapitel: hirschfeld.in-berlin.de , section Our work / Memorial / Grave site in Nice .

- ↑ EJ Haeberle: Introduction to the anniversary reprint by Magnus Hirschfeld, "The Homosexuality of Man and Woman", 1914 , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 1984, pp. V – XXXI.

- ↑ Hirschfeld 1938, p. 260; quoted from George M. Fredrickson: Racism - A Historical Outline. Hamburger Edition , 2004, ISBN 3-930908-98-0 , page 164.

- ↑ Hirschfeld 1938, p. 57; quoted from George M. Fredrickson: Racism - A Historical Outline. Hamburger Edition, 2004, ISBN 3-930908-98-0 , p. 164.

- ↑ Manfred Herzer: Magnus Hirschfeld. Life and work of a Jewish, gay and socialist sexologist. Frankfurt (Main) / New York 1992, p. 85.

- ↑ Herzer, p. 86.

- ↑ Herzer, p. 91.

- ↑ Herzer, p. 147.

- ↑ Ralf Dose: In memoriam Li Shiu Tong (1907-1993) on the 10th anniversary of his death on October 5, 2003. In: Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft, Heft 35/36, Berlin 2003, pp. 9-23 (= Dose), p. 9, note 1.

- ↑ a b Dose, p. 15.

- ↑ Edited 2013 by R. Dose; see literature.

- ↑ Dose, p. 18.

- ^ Dose, Ralf: There is still a suitcase in New York - a preliminary inventory (with list of documents). In: Communications of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, issue 46/47, Berlin 2011, pp. 12-20.

- ↑ See the report by Donald W. McLeod: http://lgbtialms2012.blogspot.de/2012/07/serendipity-and-papers-of-magnus.html

- ↑ Hirschfeld: The world trip of a sex researcher. Brugg 1933, p. 12.

- ^ Benedict Friedlaender: Renaissance des Eros Uranios , Schmargendorf-Berlin 1904, p. 57.

- ^ J. Steakley: The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany , New York 1975, p. 118.

- ↑ JE Bauer: Queerness and the generosity of nature. About Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's appeal to Magnus Hirschfeld's concept of a “third gender” . In: Capri 44 (January 2011), pp. 22-35.

- ↑ Claudia Bruns: Hirschfeld and the theory of the "third gender" . In: dies .: Politics of Eros. The Men's Association in Science, Politics and Youth Culture (1880–1934) , Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-14806-5 , p. 129.

- ↑ Rainer Herrn: Personenlexikon der Sexualforschung 2009, p. 290.

- ↑ Seeck (2003) ibid. P. 18, fn. 26.

- ↑ Claudia Bruns: Hirschfeld and the theory of the “third gender” , in: dies .: Politics of Eros. The Men's Association in Science, Politics and Youth Culture (1880–1934) , Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2009, p. 131.

- ↑ Claudia Bruns: Hirschfeld and the theory of the “third gender” , in: dies .: Politics of Eros. The Men's Association in Science, Politics and Youth Culture (1880–1934) , Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2009, p. 126 ff.

- ↑ Bruns, ibid. P. 134, p. 139.

- ↑ Seeck (2003) ibid. P. 18.

- ↑ Manfred Herzer: Magnus Hirschfeld's doctrine of the sexual intermediate stages and historical materialism , in: Das Argument 293 (September 2011), p. 566 ff.

- ↑ Sigusch, Volkmar: 50 years later , in: Sexualmedizin 1983, Issue 12.

- ↑ Volkmar Sigusch: Was Magnus Hirschfeld a “spiritual forerunner of fascism”? (1995) . In: Andreas Seeck (Ed.): Through science to justice? Text collection on the critical reception of Magnus Hirschfeld's work , ibid. P. 126.

- ↑ Hirschfeld: Gender , third volume (1930), quoted by Hans-Günter Klein (1983) in: Seeck, ibid. P. 28.

- ↑ Andreas Seeck: Introduction, in: ders. (Ed.): Through science to justice? Text collection on the critical reception of Magnus Hirschfeld's work (= series: Gender - Sexuality - Society, Vol. 4), Lit Verlag, Berlin / Münster, etc. 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6871-0 , pp. 12-14.

- ^ Rainer Herrn: Magnus Hirschfeld , in: Volkmar Sigusch, Günter Grau (eds.): Personenlexikon der Sexualforschung , Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-39049-9 , p. 291.

- ↑ Martin Dannecker: Foreword. In: Wolfgang Johann Schmidt (Hrsg.): Yearbook for sexual intermediate stages. Selection from the years 1899–1923. Frankfurt a. M./Paris 1983, pp. 5-15.

- ↑ Heinz-Jürgen Voss: Hirschfeld between movement and science , in: Rüdiger Lautmann (ed.): Caprices. Moments of gay history , Männerschwarm Verlag, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-86300-167-4 , pp. 103/104.

- ↑ Ulf Lippitz: Boys in Love , Der Tagesspiegel, June 8, 2007.

- ^ Claudia von Zglinicki: A blooming subculture: discovered in criminal files from the Nazi era , Friday, July 2, 1999.

- ↑ Another bank ( Memento from May 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) and Berlin is getting another bank ( Memento from May 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Christine Lemke on the exhibition curated by Rainer Herrn and designed by Eran Schaerf and Christian Gänshirt in: http://www.textezurkunst.de/71/gedachtnisspiegelung/ accessed on May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Press release of the Federal Ministry of Justice , August 31, 2011, accessed on September 2, 2011.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hirschfeld, Magnus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ramien, Th. (Pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German neurologist, sex researcher, pioneer of the homosexual movement and author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 14, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kolberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 14, 1935 |

| Place of death | Nice |