Helene Stocker

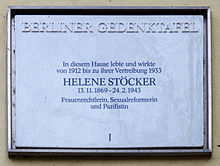

Helene Stöcker (born November 13, 1869 in Elberfeld (now part of Wuppertal ); † February 24, 1943 in New York City ) was a German suffragette , sex reformer , pacifist and publicist . In 1905 she founded the Bund für Mutterschutz ( German Federation for Maternity Protection and Sexual Reform from 1908 ), which campaigned for unmarried mothers and their children.

Life

Helene Stöcker grew up as the oldest of eight children in a middle-class and Calvinist family in Elberfeld. Her father, Peter Heinrich Ludwig Stöcker, owned a textile business from whose income the family could live well. Her mother, Hulda Stöcker (née Bergmann), was responsible for the household and raising children. Helene Stöcker left her parents' home in 1892 and moved to Berlin , where she joined the growing women's movement. In Berlin she began training as a teacher, although - as she wrote herself - she never wanted to be a teacher. After completing her training, she attended the “first high school course for women” in Berlin. From 1890 she was occupied with the works of Nietzsche and shared some of his radical views on the state, the church and the prevailing moral concepts. She was encouraged in this by Alexander Tille , a vehement advocate of social Darwinism , with whom she had been close friends for several years since 1897. Helene Stöcker published her first poems and short stories in magazines such as the Breslauer monthly papers , the Deutsches Dichterheim or the German Homeland and was supported by Ernst Scherenberg and Ludwig Salomon (1844-1911).

In 1896, Helene Stöcker began studying literary history , philosophy and economics at the University of Berlin . At that time, women were only allowed to attend German universities as guest students and with the personal permission of the lecturer. A degree was not possible for the women studying. Stöcker attended lectures by Erich Schmidt and Wilhelm Dilthey , among others . She was one of those Dilthey students who worked on his Schleiermacher studies . Other professors made use of their right to ban women in their courses. The medievalist Karl Weinhold forbade her to attend his lectures. She later tells of the historian Heinrich von Treitschke that when she asked to hear his lectures, he replied: "The German universities have been meant for men for half a millennium, and I don't want to help destroy them."

After studying in Glasgow, Helene Stöcker did her doctorate in 1901 at the University of Bern in Switzerland - on the artistic conceptions of Romanticism - as Dr. phil. Her doctoral supervisor was Oskar Walzel , who later taught in Bonn and was persecuted there by the National Socialists . After completing her doctorate, Helene Stöcker returned to Berlin. In the first years she worked as a freelance lecturer and writer in order to achieve her own "economic independence". Among other things, she taught at the Lessing University in Berlin and gave lectures across Germany on women's education and women's rights.

As one of the most prominent women's rights activists, she was in contact with numerous personalities of her time. These included Sigmund Freud , the liberals Friedrich Naumann and Hellmut von Gerlach ; Ricarda Huch , the writer and pacifist Kurt Hiller , the social democratic politician Eduard David and Lily Braun .

Helene Stöcker wrote about her extensive commitment that social justice had to be combined with individual development opportunities. "Nietzsche and socialism", that was her motto.

When the National Socialists came to power in 1933, she fled to Sweden via Switzerland . Stöcker, the staunch opponent of all anti-Semitic ideas, recognized the "horrors of the persecution of the Jews" early on.

In Stockholm, the Association for the Protection of German Writers organized a birthday party for Helene Stöcker on November 13, 1939, in which her international significance was once again made clear. With difficulty, she managed to escape via the Soviet Union and Japan to the United States , where she died of cancer in New York in 1943, completely penniless .

Women's rights movement and sexual reform

For Helene Stöcker, it was essential that both genders had equal status in the family and that men and women had equal sexuality. This included protecting unmarried mothers and illegitimate children. Therefore she campaigned for a “parental right” towards the child (instead of the prevailing “father right”, which she considered to be just as inadequate as the “mother right” demanded by some women's rights activists), d. This means that both parents should be equally necessary and significantly involved in the upbringing. “I am convinced that every child has the right to both parents; For psychological reasons, both the masculine and the feminine principle are needed. ”Since sexuality is“ one of the highest pleasures of man ”, renunciation cannot be a solution; rather, it is about "making this highest joie de vivre accessible to as many people as possible."

Her union for maternity protection and sexual reform , founded in 1905, not only helped “ fallen girls ”, but also carried out sex education and dealt with questions about contraception and sexual hygiene . The federal government promoted his ideas with the monthly magazine Die Neue Generation , in which numerous prominent contemporaries such as Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Naumann published, but also women's rights activists such as Maria Lischnewska . In 1912 the federal government expanded into an international association, of which Helene Stöcker was chairman until 1933. In 1909, Stöcker and Käthe Stricker from Bremen started an initiative vis-à-vis the Bremen Senate to protect unmarried mothers in particular.

Helene Stöcker actively campaigned for the sexual liberation of women. In her magazine Die Neue Generation she called for a new ethic , in particular that women and men should be allowed to live their sexuality freely and independently outside of marriage. Stöcker pleaded for birth control and for the impunity of male homosexuality . Her commitment to the right to abortion was closely related to her commitment to eugenics and, as she put it, "for racial education". Stöcker underlined how important Nietzsche's demands were with regard to eugenics, to the “higher-up planting, as Nietzsche put it. The command: 'You shouldn't kill', said Nietzsche, was a naivete compared to the seriousness of the prohibition of life 'You should not beget' towards unsuitable people. ”Nonetheless, the pacifist and resolute opponent of anti-Semitism separated worlds from the murderous ideas National Socialists.

Their positions represented mackerel in numerous publications, which they in renowned newspapers and journals such as the day in which of Maximilian Harden published future , in youth or that of Alfred Kerr issued Pan was able to publish. Stöcker's book "Love and Women" met with a great response and was published in an enlarged edition in 1908.

Some women's rights activists, including Helene Lange , found their liberal attitude towards sexuality to be too radical. The bourgeois Federation of German Women's Associations refused to include the Federation for Maternity Protection because of its progressive sexual ideas . Nevertheless, at the turn of the century, Stöcker's views aroused benevolent interest: “If I had 'radical' views on some points, this was viewed benevolently as an outgrowth of my youthful enthusiasm. I was invited a lot ”; She gave her lectures on women's rights, Nietzsche and literature in literary societies, but also in the private homes of industrialists and bankers. In this way she also succeeded in putting the demand for self-determination about one's own body and one's own sexuality on the agenda of the large women's organizations. Sex reformers also campaigned for the right to abortion under the heading of racial hygiene or eugenics.

The bourgeois women's rights activists supported Helene Stöcker at the outbreak of the First World War - despite Stöcker's pacifist stance - in the initiative “State aid for illegitimate children”, which called for war support for illegitimate children to be equated with that for legitimate children. In fact, Stöcker and her colleagues succeeded in getting this new regulation accepted in the Reichstag.

Since her studies she has also been involved in women's studies . Together with a few fellow students, she founded the Association of Studying Women in Berlin, which in 1906 merged with similar associations to form the Association of Associations of Studying Women in Germany .

Peace activist

When the First World War broke out , Helene Stocker's area of interest shifted and she became active in the peace movement. “A feeling that makes people so bestial towards everyone who lives outside their national borders cannot be a good thing,” she noted in her diary in August 1914. Despite increasing censorship, during the war years she wrote against the war in the New Generation and in other newspapers that still gave her the opportunity. In 1915 she joined the pacifist alliance New Fatherland founded in 1914 . The monthly newspaper Die Neue Generation , which she published, opened her up to pacifist positions.

After the war, together with René Schickele , Magnus Hirschfeld and other activists, she campaigned for the establishment of a democratic-socialist republic at the end of 1918, but also protested against a peace that contradicted Woodrow Wilson's ideas and gave the German Reich areas such as Alsace Wanted to take Lorraine down without a referendum.

Together with Kees Boeke and Wilfred Wellock was 1921 in Bilthoven , the War Resisters' International founded (WRI) for the time being under the name PACO. Her fellow campaigners against the war included Hedwig Dohm , Harry Graf Kessler , Walther Schücking , Hellmut von Gerlach , Elisabeth Rotten and Minna Cauer . Like other peace activists, Helene Stöcker placed great hopes in Woodrow Wilson's message of peace. In 1926, Stöcker joined the Association of Military Service Opponents (BdK) founded by Kurt Hiller . After the First World War she called for the abolition of the Reichswehr and all other armies.

Out of outrage about the positive attitude of the churches towards the First World War, she resigned from the church in January 1915.

Honors

- In Wuppertal a part of the river Wupper is named after Helene Stöcker.

- The Helene Stöcker memorial has stood on Schulstrasse in Wuppertal since May 2014. The design comes from Ulle Hees and Frank Breidenbruch.

Books and writings

- On the view of art in the 18th century: From Winckelmann to Wackenroder (= Palaestra , Volume 26), Mayer & Müller, Berlin 1904, DNB 362818282 Dissertation University of Bern 1902, 122 pages ( OCLC 23450077 ).

- Love and women . A manifesto of the emancipation of women and men in the German Empire. Minden: Bruns, 1906. Second through. u. Probably ed. Minden: Bruns, 1908.

- Crisis-making . A clearance. 1910

- Marriage and cohabitation . 1912

- (Ed.): Karoline Michaelis . Letters. 1912

- Ten years of maternity leave . 1915

- Gender Psychology and War . 1915

- Sex Education, War and Maternity Protection . 1916

- Modern population policy . 1916

- Petitions from the German Confederation for Maternity Protection 1905–1916 . 1916

- Resolutions of the German Confederation for Maternity Protection 1905–1916 . 1916

- The love of the future . 1920

- The becoming of the new morality . 1921

- Love . Novel. New Generation Publishing House, Berlin 1922

- Eroticism and altruism . 1924

- Herald and Realizer . Contributions to the problem of violence. 1928

Magazines:

- Women's Rundschau, 1903–1922

- Maternity Protection. Journal for the Reform of Sexual Ethics (Federal Organ for Maternity Protection), published from 1905 to 1907, then renamed to:

- The New Generation , 1908–1933

Individual contributions:

- Old and new gender morals . In: Heinrich Schmidt (Ed.): Blätter des Deutschen Monistenbundes, No. 17, November 1907 . Breitenbach, Brackwede 1907.

- Decline in the birth rate and monism . In: Willy Bloßfeldt (Ed.): The Düsseldorfer Monistentag. 7th Annual General Meeting of the German Monist Federation from 5. – 8. September 1913 . Unesma, Leipzig 1914.

literature

- Helene Stöcker: Memoirs. The Unfinished Autobiography of a Woman Moving Pacifist , ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin, Kerstin Wolff, Foundation Archive of the German Women's Movement, Kassel (= L'homme Archive , Volume 5). Boehlau, Cologne 2015, ISBN 978-3-412-22466-0 . (Review in FAZ: http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/buecher/rezensions/sachbuch/erinnerungen-der-frauenrechtlerin-helene-stoecker-13991090.html ).

- Rolf von Bockel: philosopher of a “new ethic”. Helene Stöcker (1869–1943). Edition Hamburg Bormann and von Bockel, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-927858-11-0 .

- Gudrun Hamelmann: Helene Stöcker, the “Bund für Mutterschutz” and “The New Generation”. Haag and Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-89228-945-X .

- Schumann, Rosemarie: Helene Stöcker. Herald and Realiser, in: Olaf Groehler (Ed.): Alternatives. Fates of German citizens . Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1987, pp. 163-195, ISBN 3-373-00002-5 .

- Annegret Stopczyk-Pfundstein: philosopher of love. Helene Stocker. BoD, Norderstedt 2003, ISBN 3-8311-4212-2 .

- Martina Hein: The connection between emancipatory and eugenic ideas in Helene Stöcker (1869-1943). Microfiche edition, 3 microfiches, Bremen 1998, DNB 955 529 352 (dissertation University of Bremern 1998, 230 sheets).

- Christl Wickert : Helene Stöcker 1869–1943. Suffragette, sex reformer and pacifist. A biography. Dietz, Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-8012-0167-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Helene Stöcker in the catalog of the German National Library

- Heike Schaal: Helene Stöcker. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Helene Stöcker: The pioneer for maternity protection and social reform, detailed biography

- Short biography (on calendar sheet September) (PDF file; 930 kB)

- Hedwig Richter : Memories of Helene Stöckers. Spiritually, the great love and good of the Sex Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 1, 2016, accessed on January 3, 2016

- Anja and Doris Arp: November 13th, 1869 - birthday of Helene Stöcker WDR ZeitZeichen on November 13th, 2019 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wickert (1991): 26.

- ^ Sophie Pataky : Lexicon of German women of the pen . A compilation of the works by female authors that have appeared since 1840, along with the biographies of the living and a list of pseudonyms. Carl Pataky, Berlin 1898 ( zeno.org [accessed on November 13, 2019] Lexicon entry "Stöcker, Helene").

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 54 f.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, p. 53.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 54.

- ↑ Hamelmann (1992): 23.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 91 f.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 121.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 263.

- ↑ Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff: Memoirs of Helene Stöcker. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, p. 261, note 739.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs. The Unfinished Autobiography of a Woman Moving Pacifist, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin and Kerstin Wolff, Boehlau Verlag, Cologne 2015, 87.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne, p. 168.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, p. 93.

- ↑ Irene Stoehr: Influence of Women or Gender Reconciliation? On the “Sexuality Debate” in the German women's movement around 1900 , in: Johanna Geyer-Kordesch and Annette Kuhn (eds.): Women's Body Medicine Sexuality , Schwann-Bagel Düsseldorf 1986, on the New Ethics of Helene Stöckers pp. 159–191, ISBN 3-590 -18040-4 .

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Becoming the sexual reform for a hundred years, in: Hedwig Dohm u. a. (Ed.): Marriage? To reform sexual morality. Berlin 1905, pp. 36-58.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne, p. 125.

- ↑ The newspaper “Tag” was founded in 1900 by the publisher August Scherl . With its red underlined heading - a novelty in media history - it was also called “Red Day”, cf. Stöcker: Memoirs, 122 f.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 94.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, p. 180 f.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, p. 257.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker: Memoirs, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 41.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, 191.

- ↑ Bruna Biancho: Towards a New Internationalism: Pacifist Journal Edited by Women 1914-1919, in: Christa Hämmerle and others (eds.), Gender and the First World War. London 2014, pp. 176-194, esp. 178.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne, p. 319.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 97 f.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, p. 210, 223-225 u. 230

- ↑ Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff: Memoirs of Helene Stöcker. Cologne: Böhlau, 2015, p. 336.

- ↑ Helene Stöcker (2015): Memorabilia, ed. by Reinhold Lütgemeier-Davin u. Kerstin Wolff. Cologne: Böhlau, 203.

- ^ A b Anne Grages: A philosopher of love with hat and secret . In: Westdeutsche Zeitung . May 31, 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stocker, Helene |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German women's rights activist, sex reformer, pacifist and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 13, 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Elberfeld |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 24, 1943 |

| Place of death | New York City |