Anarchism in Spain

The anarchism learned above all in Spain support and had a significant impact in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939, until the takeover of Francisco Franco .

A social revolution , as a result of which land and factories were collectivized and administered by the working class , spread across Spain. In Catalonia and its capital Barcelona , anarcho-syndicalism prevailed in the majority. There were also other types of anarchism, especially in Saragossa , and in the form of farmers' associations in Andalusia . The anarchists played a central role in the resistance against the Franquists , a heterogeneous alliance composed mainly of conservatives, fascists , the military, monarchists and Catholic groups. The revolution was ended with Franco's victory in 1939, and the anarchist activists were forced underground, imprisoned or executed. Resistance to this rule never entirely died out, with militants participating in acts of sabotage and other direct actions , and by making various attempts to kill the ruler.

Usually police repression reduced the early activities of Spanish anarchists, but at the same time it radicalized many members. These cycles led to increased violence in the early 20th century, when armed anarchists and “pistoleros,” armed men paid by business owners, were mutually responsible for political assassinations.

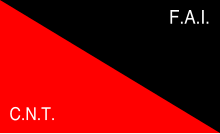

In the 20th century this violence faded and the movement gained momentum with the rise of anarcho-syndicalism and the creation of a large union libertarian union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT - National Labor Association). General strikes became normal and large parts of the Spanish working class adopted anarchist ideals. The Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI - Iberian Anarchist Federation) was created as a purely anarchist organization, with the intention of having the CNT focused on the principles of anarchism.

The legacy of Spanish anarchism remains important to this day, especially the short summer of anarchy , with few other examples such as Ukrainian anarchism, represents one of the most important reference models of anarchism.

history

Beginning

In the mid-19th century, revolutionary ideas were largely unknown in Spain. Most likely the radical movement is the followers around Pierre-Joseph Proudhon , who was known as a federalist , in addition, the ideas of French early socialists such as Charles Fourier or Étienne Cabet played a role. Attitudes that were later associated with anarchism, such as anti-state or anti-church thinking, were widespread, but not part of a general philosophy. There was increased peasant unrest in many parts of the country, but these were not in connection with any political movements, but rather due to the repressive prevailing conditions. The same was true of the cities. Even before workers knew about anarcho-syndicalism, there were general strikes and other conflicts between workers and employers.

The first successful attempt to make anarchism known in Spain took place after the successful September Revolution in 1868 , as a result of which Queen Isabella II was overthrown. The young Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Fanelli came to Spain on a trip planned by Mikhail Bakunin , with the intention of winning members for the International Workers' Association . In the winter of 1868/69 Fanelli went to Madrid , and later to Barcelona . He met with many Spanish trade unionists such as Anselmo Lorenzo and Rafael Farga Pellicer and the first sections of the International were formed. The first section of the International was provisionally founded in Madrid as Núcleo and later constituted as the provisional national section of the International in Spain. A few dedicated Spaniards, fascinated by Fanelli's idea, began arranging meetings, giving speeches and recruiting new members. Giuseppe Fanelli traveled on to Barcelona in January 1869, where he promoted the formation of the first section, which was founded on May 2, 1869.

By 1870, the number of members in Madrid grew to around 2,000. Further sections were formed shortly afterwards in other major cities in Spain such as Cádiz , Seville , Saragossa and Palma . Most support for anarchism was in industrial Barcelona , a bastion of proletarian resistance, Luddism , and the trade unions . These centers of revolutionary activity spread the anarchist idea through speeches, discussions, meetings and through their own newspapers La Solidaridad , which appeared in Madrid for the first time on January 15, 1870, La Federaciòn from Barcelona and El Obrero from Palma de Mallorca. The anarchist ideas spread even faster than in the cities among the rural population, many of whom had come into existential hardship as a result of far-reaching land reforms.

A major event of those years was the Barcelona Congress of 1870, held from June 19th to 25th at the Teatro del Circo . The Spanish Section of the International was renamed the Spanish Federation here and directions for future organizations were discussed. At the congress, the success of the agitation trip for the International was shown: after 1½ years there were already 150 sub-societies in Spain with around 40,000 members.

In 1871, the socialists and liberals in the Spanish Federation wanted to reorganize Spain into five trading sections ( comarcas ) with various committees and councils. Many anarchists feared that this initiative would centralize the Spanish Federation . A year of conflict followed, in which the anarchists were finally able to prevent the plan. The Spanish Federation tried to organize itself decentrally and depending on the actions of the broad mass of workers and no longer in bureaucratic councils. Even before the Hague Congress of the International in September 1872, the Spanish Federation, with 848 local sections, was by far the largest national organization of the International and was predominantly anarchist.

In 1872 Mikhail Bakunin was expelled from the International together with James Guillaume . The Spanish Sections then decided with the other anti-authoritarian sections from Italy , France , Belgium , Holland , England , the USA and the Swiss Jura to form the Anti-Authoritarian International .

Early highs 1873 to 1890

In the Alcoy region in 1873 workers struck for the eight-hour day , with lively support from the anarchists. The conflict turned violent when police fired at the unarmed crowd, causing workers to storm the town hall. Dozens of people were injured and killed on both sides when the conflict ended. Sensational stories were spread about atrocities that had never happened: priests who were crucified, men who were showered with gasoline and set on fire, etc.

The government wanted to end the activities of the Spanish Federation as soon as possible. Meeting places and workers' bars were closed, members arrested and publications banned. Still, anarchist ideas remained popular, especially in the rural areas, where committed peasants instigated several series of unsuccessful rebellions. By 1870 the Spanish Federation had most of its members in the rural areas of Andalusia and Catalonia . These minor achievements were largely destroyed by the state, which succeeded in forcing the entire movement underground in the mid-1870s. The Spanish Federation lost membership and conventional unions began to replace revolutionary actions for a while. Attempts to form mass organizations, such as the Pact of Unity and Solidarity , were unsuccessful in the long run. The Spanish anarchist sections reached their temporarily largest membership in 1883 with almost 60,000 members.

Anarcho-syndicalism and educational projects

Bomb attacks and assassinations became increasingly rare around the turn of the century. The vast majority of anarchists viewed these methods as counterproductive and many complained that the anarchist movement was alienated from the masses. One went back to the roots of the anarchist movement in Spain and there was a resurgence of anarcho-syndicalism . Since assassinations and attacks made the syndicalist work very difficult, anarcho-syndicalists themselves increasingly worked to contain the violence. This included agitation against violence and, in some cases, cooperation with the police in preventing such attacks. So-called pure anarchists , on the other hand, criticized syndicalism as reformist, but these increasingly lost importance.

The May Day demonstrations held in the United States and around the world in the wake of the Haymarket Massacre of 1886 were strongest in Spain. May 1st, 1890, marked the beginning of the largest wave of strikes in Europe to date, which was only declared to have ended in general on May 8th. The strike was carried out on the largest scale in Catalonia under a state of siege, preventive arrests and repression of the press.

The Spanish government always reacted repressively to these developments and used the police and the military with great severity against striking workers. The year 1891 saw the dissolution of most of the organizations in Spain, some lawsuits and the persecution of the most active activists. Some anarchist circles responded to the precarious situation of the Spanish anarchist organizations with attacks. Revolts, such as those in Jerez de la Frontera in 1892, were quickly put down by the government. Anarchists were met with severe violence, such as the mass arrest and torture of anarchist prisoners in Montjuïc prison in Barcelona in 1892. More than 400 people were thrown into the dungeon in response to a bomb attack (the culprit was never found). International outrage was high when it became known that the prisoners were being tortured: men dangling from the roof, their genitals mutilated and burned, with torn fingernails, etc. Many died before they even came to court, five were executed.

This situation made the activity of anarchist organizations very difficult and further periods of severe persecution followed in 1893 and 1896. After an upswing in 1898 and 1899, a new organization, the Federación de Trabajadores de la Región española (Federation of Workers of the Spanish region), which combined syndicalism with libertarian principles and whose participants were then estimated at 52,000.

In parallel with the syndicalist efforts, educational projects among the Spanish anarchists also played an important role. With new educational concepts, ways were sought to combat illiteracy , which in Spain was widespread in well over half of the population. Francisco Ferrer played a special role with his Escuela Moderna ( Modern School ). After the first school was founded in Barcelona in 1901, the number of schools grew to around 60 by 1906 and became a model for similar schools around the world.

The "tragic week"

→ Main article: Tragic week

Two events in 1909 fueled another general strike in Barcelona. A textile factory with 800 workers was closed and the workers dismissed without notice. Wages were cut across the industrial sector. Workers, also outside the textile industry, began to organize a major general strike. At the same time, the government announced that military reserves, mainly from the working class, were being drawn up for the war in Morocco. The move met with resistance from workers and anti-war meetings were held across the country.

The strike began in Barcelona on July 26, a few weeks after the reservists were due to be called up. It quickly developed into a riot. Anselmo Lorenzo wrote in a letter: “A social revolution has broken out in Barcelona and it was initiated by the people. Nobody led them. Neither the liberals, nor the Catalan nationalists, nor the republicans, nor the socialists, nor the anarchists. ” Police stations were broken into. Train lines leading to Barcelona were destroyed. Barricades were erected on the streets. Eight churches and various monasteries were destroyed by members of the Republican Radical Party , and six people were killed. After the revolt, around 1,700 people were charged with various crimes. Most were released and 450 were sentenced. 12 were sentenced to life imprisonment, five were executed, including Francisco Ferrer, who was not even in Barcelona at the time of the revolution.

Because of this "tragic week", the government began to persecute people who were critical of the government even harder. Unions have been banned, newspapers have been banned, and liberal schools have been closed. Catalonia was placed under martial law until November .

The rise of the CNT

At the beginning of the 20th century, most Spanish anarchists agreed that there had to be a national organization to bring more energy into their movement. This organization, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), was founded in October 1910 during a congress of the Solidaridad Obrera . During the congress a resolution was passed defining the purpose of the CNT as "... promoting the economic emancipation of the entire working class through the revolutionary dispossession of the petty bourgeoisie" . When it was founded, the CNT had around 30,000 members from various associations and organizations, which is comparatively few from a later point of view (later the CNT had more than 1,000,000 members).

The central organizational structure of the CNT was constantly decentralized and divided into regional alliances, which were divided up again if necessary. In this way most of the tedious bureaucracy was banished. Decision-making initiatives came directly from the small, individual associations. There were no paid civil servants; all posts were occupied by normal workers. Decisions made by the National Delegation did not have to be followed. From this point of view, the CNT had little in common with similar socialist organizations.

A general strike was called just five days after it was founded. The strike spread to various cities in Spain; in one city the workers took over the city administration and killed the mayor. In response, government troops were sent to every major city and the strike was quickly crushed. The CNT became an illegal organization and its activists were forced underground just a week after it was founded.

In 1917 a general strike organized by socialists, with the substantial help of anarchists, broke out in Barcelona. Barricades were erected and the strikers tried to stop the tram. The government responded with the toughest force using weapons. The balance was 70 dead. Contrary to what the violence used suggests, the claims made were moderate, typical of a socialist strike of the time.

The CNT after the First World War

Spain's economy suffered severe damage from the general decline in the wartime economy. Factories closed, unemployment increased, and salaries cut. As many capitalists expected a class conflict , especially as a result of the February 1917 Revolution in Russia, many of them began a bitter struggle against the unions, especially the CNT. Factory closures became more frequent. Known militant members of the unions were listed, and contract killers were hired to kill union leaders. Many hundreds of anarchists were killed during this time. The anarchists, for their part, responded with attacks, the most famous of which was the murder of the Spanish Prime Minister Eduardo Dato .

The CNT had nearly a million members at the time. It mainly focused on direct action and syndicalism . Revolutionary ideas were no longer unknown, but more and more accessible to the mainstream . A powerful upper-class opponent, Díaz del Moral , said that “the entire working population” was infected with the spirit of the revolution.

Organizations formed where anarchism was previously unknown in Spain, even in the smallest of villages. Different parts of the CNT (trade unions, regions etc.) were now autonomous and yet interconnected. A strike by workers from one group often led to a solidarity strike by other workers in another city.

General strike 1919

In 1919, workers at a power station in Barcelona triggered a 44-day, largely successful general strike with more than 100,000 participants. Employers immediately tried to respond by military means, but the strike spread far too quickly. Workers at another factory staged a sit-in to support their colleagues. About a week later, all textile workers were on strike. Soon afterwards, almost all workers in the electrical industry went on strike.

Barcelona was placed under martial law, but the strike continued. The newspaper printers union warned Barcelona publishers that they would not print anything critical of the strikers. The government in Madrid tried to end the strike by calling all workers to military service, but the call failed because it did not even make it into the newspapers. When the call to the army did reach Barcelona, another strike, this time the railroad workers and truck drivers, was the answer.

The government of Barcelona finally managed to end the strike that had largely brought industrial production in Catalonia to a standstill. The strikers called for the eight-hour day, trade union recognition, and the reinstatement of sacked strikers. All demands were conceded, but not the demand to release all political prisoners. The government agreed, but refused to release those whose trial was pending. The workers responded with the slogan: "Free everyone!" And warned that the strike would continue in three days if this demand was not met. The police stopped the second strike before it could reach a large scale, with members of the strike committee and many others being immediately detained. The government tried to get closer to the workers who were clearly on a revolutionary course . Tens of thousands of unemployed workers returned to work. The eight-hour day was decided for all employees. Spain became the first country in the world to pass a nationwide eight-hour day law as a result of the general strike of 1919.

After the general strike of 1919 there was increasing violence against the organizers of the CNT, in connection with the rise of Miguel Primo de Rivera to dictator , who banned all anarchist organizations and publications, so that the anarchist movement could only continue its activities from underground . Many anarchists responded to the reprisals with assassinations. This was a period of constant violence when anarchist groups, including Los Solidarios and the entrepreneur-funded Pistolero groups, murdered their respective political opponents.

The FAI

During the Primo de Rivera years, many of the CNT leaders began to adopt more moderate views, showing a perspective that anarchist hopes would not be fulfilled immediately or in a short time. The Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI - Iberian Anarchist Federation) was founded in 1927 to combat this tendency.

Their organization was based on autonomous reference groups , including Los Solidarios . Estimates of the membership immediately before the revolution assume 5,000 to 30,000 members. The number of members rose sharply in the first months of the civil war. The FAI was not ideally libertarian and was dominated by militants like Juan García Oliver and Buenaventura Durruti . However, she was not authoritarian in the methods used; it allowed the freedom to have a different opinion than its members. In fact, the organization was loosely structured, unlike the Alliance of Bakunin .

With actions like general strikes or bank robberies to raise money, the FAI was definitely militantly revolutionary in the beginning, but over time it became clearly more pragmatic. She supported moderate efforts against the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and helped create the Popular Front of Spain in 1936 . At that time, when the anarchist organizations began to work with the Republican government, the FAI became a de facto political party and the model of affinity groups was dropped.

The Riveras case and the Second Spanish Republic

The CNT initially welcomed the Second Spanish Republic as a preferable alternative to dictatorship, but stuck to the principle that all state power is destructive.

However, this relationship did not last long. A telephone workers' strike sparked street fighting between the CNT and government forces; the army used machine guns against the workers. A similar strike broke out in Seville a few weeks later ; twenty anarchists were killed and one hundred wounded after the army captured a meeting place and destroyed it with artillery. An uprising broke out in Alto Llobregat , with miners taking over the town and raising red and black flags in the town halls.

These actions provoked harsh political repression on the part of the government and achieved little noticeable success. Some of the most active anarchists - including Durruti and Ascaso - were deported to Spanish possessions in Africa. This provoked protests and a riot in Terrassa , where, as in Alto Llobregat, workers stormed the town hall and raised their flags. Another unsuccessful uprising came in 1933 when anarchists attacked military camps in the hope that the soldiers inside would support them. The government had already learned of these plans in advance and quickly suppressed the revolt.

Thousands of anarchists were subsequently imprisoned. At the same time, the CNT was experiencing internal disputes triggered by the so-called Manifesto of Thirty .

Prelude to the Revolution

The national focus on the republic and reforms led the anarchists to the exclamation: “First social reforms before elections!” From their point of view, liberal electoral reforms were in vain and undesirable and hindered the total liberation of the working classes.

Another uprising took place in December 1933. Except for a prisoner liberation in Barcelona, however, the revolutionaries achieved nothing until the police put down the revolt in Catalonia and most of the country. In Zaragoza, however, there was a brief uprising in the form of street fighting and the occupation of certain buildings.

In Casas Viejas , some militant workers quickly surrendered when they were surrounded by police. However, an old anarchist nicknamed " Six Fingers " barricaded himself in his home with his family and vowed to resist his arrest. His house was burned down and his family killed as well as the anarchists who had previously surrendered peacefully. The Casas Viejas massacre provoked storms of indignation, including on the part of conservative Republicans.

A major strike took place in April, again in Zaragoza. It lasted five weeks and it paralyzed almost the entire economy of Zaragoza. Other parts of the country supported the strike.

Asturias

Heralds of the coming revolution (and civil war) were probably most evident in 1934 in the Asturias region . There, anarchists, socialists and communists jointly organized a strike, in which the latter, despite their small number, exerted a strong influence, as they were supported by the Soviet Union. For comparison: Communists had about 1,000, the UGT 1,440,000 and the CNT 1,580,000 members.

The miners' strike began with attacks on the Civil Guard barracks , and in the town of Mieres even the police stations and the town hall were taken over. The strikers continued to occupy cities, including the capital of Asturias, Oviedo . The workers took control of most of Asturias with slogans such as "Unite, Proletarian Brothers!" The ports of Gijón and Avilés remained open. But since the well-resourced communists refused, out of suspicion, to adequately arm the militant anarchists who wanted to defend themselves against the incoming government troops, the government was able to suppress the uprising by force.

The operation of the Spanish Foreign Legion led by General Lopez Ochoa and the order to kill Spaniards caused public outrage. Captured miners were tortured , raped , maimed and executed . This gave an indication of the brutality that would show itself two years later in the Spanish Civil War .

The Popular Front

As the parties and movements of the right-wing spectrum, such as Gil-Robles' ultra-conservative, Catholic CEDA and the Falange, grew steadily, the left-wing parties decided to join forces in a popular front along the lines of the French model . This included Republicans, Socialists, and Communists. The anarchists did not want to support the Popular Front or bring it to power, but neither did they want to fight it.

The more radical elements of the CNT-FAI were not satisfied with the electoral policy. In the months following the rise of the Popular Front to power, strikes, demonstrations and rebellions broke out across Spain. Across the country, nearly five square kilometers of land have been taken over by squatters . The Popular Front parties gradually lost control.

The CNT National Congress in May 1936 was openly revolutionary. Among the topics discussed were sexual freedom , plans for agricultural communes, and the elimination of social hierarchy .

Anarchist presence in the Spanish Civil War

The Republican government was reluctant to respond to the military build-up, despite the fact that the CNT had been warning the government for months that an uprising would break out in Morocco. However, the Popular Front did nothing and refused to give arms to the workers. As a result, CNT militants raided an arsenal and distributed the weapons to the unions. Militias were placed as alarm guards days before the planned survey.

The uprising was brought forward by two days to July 17 at short notice and it was defeated by armed workers' militias in many areas, such as Barcelona. Some anarchist strongholds, such as B. Zaragoza, fell. The government persisted in a denial stance, claiming that the “nationalist” forces had been beaten in areas where they were not. It is largely due to the militancy on the part of the anarchist and socialist unions that the rebel forces did not immediately seize power.

The anarchist militias were organized freely before they were partially absorbed into the regular army in 1937. They had no system of rank , no hierarchy, no salute, and those called "commanders" were chosen by their troops.

The most famous anarchist unit was the Durruti column , led by the famous militant Buenaventura Durruti . It was the only unit that managed to gain respect from otherwise hostile political opponents. In a section of her memoir that ridicules anarchists elsewhere, Dolores Ibárruri states: “The war developed with minimal involvement on the part of the anarchists in the fundamental operations. Durruti was an exception… ”The column started with 3,000 militiamen and at its peak numbered 8,000 militiamen. The Durruti column found it difficult to obtain arms from the Republican government and weapons confiscated from government warehouses. Durruti's death on November 20, 1936 weakened the unit's fighting spirit and tactical skills; she was later incorporated into the regular army. About a quarter of a million people attended Durruti's funeral, but Durruti's cause of death remains unclear to this day.

Another famous unit was the Iron Unit , composed of former prisoners who sympathized with the revolution. The Republican government described them as "uncontrollable" and "bandits," but the unit made a significant contribution to the successes of the war in the first phase of the war. In March 1937 they were incorporated into the regular army.

The 1936 revolution

Along with the struggle against Franquism, there was a profound anarchist revolution across Spain. Many companies in the Spanish economy were subjected to workers' rule; in anarchist strongholds like Catalonia the percentage was above 75%, but lower in areas with strong socialist influence. Factories were run by workers' committees, agricultural land was collectivized and operated as “free communes”. Companies such as hotels, hairdressing salons and restaurants were also collectivized and run by their employees. George Orwell describes a scene in Aragón during this time, in his book Homage to Catalonia :

“More or less by chance I had come to the only community of any size in Western Europe where political awareness and doubts about capitalism were more normal than the opposite. Here in Aragon one lived among tens of thousands of people, mostly, if not entirely, of the working class. They all lived on the same level under the conditions of equality. In theory there was perfect equality, and even in practice it was not far from it. In a way, one could truly say that this was a foretaste of socialism. By that I mean that the spiritual atmosphere of socialism prevailed. Many of the normal motives of civilized life - snobbery, dragging money, fear of the boss, and so on - had simply ceased to exist. The normal classifications of society had disappeared to an extent hardly imaginable in the money-laden air of England. Nobody lived there except the farmers and ourselves, and nobody had a master over themselves. "

In the collectivized areas, the basic principle was “Everyone according to their abilities, everyone according to their needs.” In some places in the anarchist-organized areas, money was completely eliminated and replaced by vouchers. Under this system, goods were often only a quarter of their previous cost.

The anarchist communes produced more than they did before collectivization. In the armaments sector in particular, there was a large increase in productivity. Instead of 25 factories in September 1936, 300 factories with a total workforce of 150,000 worked in the war industry in July 1937, where production rose by 30–40%. There was also a large increase in productivity in the service sector, particularly the Barcelona public transport system, which operated 100 more trams with 700 trams than before the coup and increased in-house production of equipment from 2% to 98%. The self-made cars were lighter and larger than the old ones, so that the income could be increased by 15-20%, although the fare had been reduced. In Catalonia, for example, agriculture increased its yields by 40%. The recently liberated zones operated on completely libertarian principles; Councils and assemblies made decisions without any kind of bureaucracy. (It should be noted that at the time, the CNT-FAI leadership was nowhere near as radical as the registered members who were responsible for these rapid changes.)

In addition to the economic revolution, there was a spirit of cultural revolution. Traditions perceived as oppressive had disappeared. For example, women were allowed to have abortions and the idea of free love became popular. In many ways this spirit of cultural revolution was similar to that of the "New Left" movement of the 1960s.

CNT-FAI collaboration with the government during the war

In 1936, after some resistance, the CNT decided to work with the government of Largo Caballero . Juan García Oliver became Minister of Justice (he cut taxes and destroyed all criminal records) and Federica Montseny became Minister of Health, to name a few members.

During the Spanish Civil War, many anarchists outside Spain criticized the CNT's leadership role in government participation and compromises with communist elements on the republican side. It is true that the anarchist movement gave up many of its principles in those years, but the Spaniards felt that this was a temporary adjustment and once Franco was defeated, the liberal way would be continued. There were also concerns about the growing power of authoritarian communists within the government. Montseny later stated: “At that time we only saw the reality of the situation we were in: the communists in government, but we outside; we saw the many possibilities and we saw all the progress that we had made in the meantime at risk. "

Indeed, some anarchists outside Spain saw these concessions as necessary in considering the cruel possibility of losing everything should the Franquists win the war. Emma Goldmann said: “When Franco stood at the gates of Madrid, I could hardly have accused the CNT-FAI of choosing the lesser evil. Participation in the government rather than dictatorship, the deadliest evil ” .

To this day, this question is controversial among anarchists.

Counter-revolution

During the civil war, the Partido Comunista de España (PCE - Communist Party of Spain) gained considerable influence due to its support from the Soviet Union . Communists and "liberals" on the republican side made a significant contribution to destroying the anarchist revolution. One communist harshly proclaimed in an interview that communists "will make short work of the anarchists after the expulsion of Franco". Their efforts to weaken the revolution were ultimately successful: the hierarchy was partially restored in many of the collectivized zones, and power was wrested from the workers and unions to be monopolized by the " Popular Front ".

Perhaps most importantly, the measures taken to destroy the militias that carried the war effort in spirit and in action. The militias were partially declared illegal and technically merged with the republican army. This had the effect of demoralizing the soldiers and depriving them of what they had ultimately fought for: not for the Soviet Union, but for themselves and their freedom. Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovsejenko , who worked for Stalin in Spain, predicted this in 1936: "Without the participation of the CNT it will certainly not be possible to maintain the right enthusiasm and discipline in the popular militias."

The counter-revolutionary activities often weakened the anti-fascist war effort. As an example: a huge arsenal was left to the Franquists for fear that the weapons might fall into the hands of the anarchists. Troops were withdrawn from the front to destroy anarchist collectives. Many able soldiers have been killed for their political ideology. A leader of the repression, Enrique Líster , said he would "shoot all the anarchists he had to." It has been revealed that many anarchists have been imprisoned under communist orders instead of being made to fight on the front lines, and so are many of them Prisoners were tortured and shot.

The event, which later became known as the Maiereignisse , saw the most dramatic repression against the anarchists in May 1937. Communist-led police forces attempted to take a CNT-led telephone building in Barcelona. The telephone workers fought, erected barricades and surrounded the communist "Lenin barracks". Five days of street fighting kills 500. This tragic series of events demoralized the workers of Barcelona.

The government later dispatched 6,000 soldiers to disarm the workers and the FAI was banned. The communists, however, were allowed to keep their weapons; only the anarchists were forced to give them up. This is no surprise because the Barcelona police and government were openly communist in those days. The " Friends of Durruti " militant group tried to continue the fight because they felt that the communists would ruin the strength of the anarchist movement. Their call was not heard.

During the civil war, various communist newspapers carried out massive propaganda against the anarchists and the POUM . They were often called “ Hitlerists ” and “Fascists” in relation to Franco, as George Orwell notes in Homage to Catalonia : “Imagine how hated it must be to see and know a 15-year-old Spaniard on a couch that well-dressed men are walking around in London and Paris who are busy writing pamphlets to prove that this little fellow is a fascist in disguise. " The unreliability of these newspapers was particularly evident, as not a single one of them about the events of the May 1937 reported in Barcelona.

The Franco years

When Francisco Franco took power in 1939, he had tens of thousands of political dissidents shot. The total number of those killed for political reasons is estimated at around 200,000. Political prisoners filled the prisons, which were twenty times more numerous than before the war. Forced labor camps were set up where , according to the historian Antony Beevor , the system was probably "as bad as in Germany or Russia" . Despite these actions, there was underground resistance against the Franco regime for decades. The actions of the resistance included, among other things, sabotage, the liberation of prisoners, the organization of underground work, the support of refugees and escaped people, and the murder of government officials.

Little attention is paid to the Spaniards who fought the Franco regime, including from Franco's former opponents. Miguel García , an anarchist who was imprisoned for 22 years, described their circumstances in his 1972 book: “When we lost the war, those who fought went into the resistance. But for the world, resistance members had become criminals because Franco made the laws, even when he decided to break the laws in the constitution in a mess with the political opposition. And the world continued to regard us as criminals. When we were arrested the Liberals weren't interested because we were 'terrorists'. "

During the Second World War , the Spanish anarchists collaborated with the French resistance and engaged in actions both at home and abroad. They worked specifically in smuggling Jewish families into Spain, providing them with passports and helping them find safe places to protect them from Nazi oppression.

The Spanish government under Franco continued to persecute “criminals” to the end. In previous years, some prisons were filled to fourteen times their capacity so that prisoners could hardly move. People were often arrested for carrying union IDs. Active militants were often even less happy; thousands were shot or hanged. Two of the most skilled resistance fighters, Josep Lluís Facerías and Francesc Sabaté Llopart , known as El Quico , were shot dead by police forces; many anarchists met a similar fate. The underground CNT was also involved, in 1962 a secret section "Internal Defense" was founded to coordinate actions of the resistance.

The guerrilla resistance died down around 1960 with the deaths of many of the more experienced militants. According to government sources, there were 1,866 clashes with security forces and 535 acts of sabotage between the end of the war and 1960. 2,173 guerrillas were killed and 420 wounded, while government figures show 307 dead and 372 wounded. 19,340 resistance fighters were arrested during this period. Those who supported the guerrillas were treated with similar brutality; over 20,000 have been arrested on this charge over the years and many have been tortured during interrogation.

During Franco's dictatorship there were at least 30 enterprises to assassinate Franco, most of them run by anarchists. In 1964 the anarchist Stuart Christie came from Scotland to kill Franco. He failed, was imprisoned, and later wrote the book General Franco Made Me a Terrorist . The Anarchist Black Cross was reactivated in the late 1960s by Albert Meltzer and Stuart Christie to aid anarchist prisoners during Franco's dictatorship.

today

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) is still active today, but was unable to continue its old meaning. In 1979 the CNT split into two factions: CNT / AIT and CNT / U. The CNT / AIT claimed the original name "CNT", which prompted the CNT / U to change its name to Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) in 1989 and to maintain most of the CNT principles. The CGT is larger than the CNT with around 60,000 members and is currently the third largest union in Spain. An important reason for the separation, and the main difference between the two unions, is that the CGT, like any other Spanish union, takes part in elecciones sindicales (syndicate elections ) in which employees elect their representatives for collective bargaining. The CGT has a large number of representatives, for example at Seat , the Spanish car manufacturer and largest company in Catalonia, and it holds the majority of the shares in Metro Barcelona . The CNT does not participate in elecciones sindicales and criticizes the model. The separation of the CNT-CGT made it impossible for the government to give the unions back important factories that they had owned before the Franco regime captured them and added them to the then only authorized union, Sindicato Vertical , a development that also happened for other historical parties and political organizations is open.

The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) has reorganized and is a member of the International of Anarchist Federations .

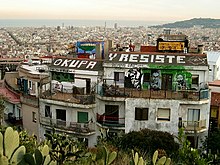

In Barcelona is squatting widely; many squatters have anarchist views. They faced strong headwinds from the government, including raids and evictions. In 2004, following the eviction of the L'Hamsa squat , squatters broke windows of banks and real estate companies, started fires, attacked police cars and sprayed slogans on city walls.

Relations with socialists and communists

Spain was the only country in Europe where the anarchists had more influence than the socialists. Scholars have suggested a number of reasons for this anomaly. Unlike many other European countries, Spain was a largely rural society. Karl Marx , on the other hand, relied on the urban proletariat as a revolutionary subject. So it is not surprising that on the one hand the Marxist ideas were unpopular or unknown among rural residents, on the other hand the population warmly embraced anarchism, a theory that shows similarities to long-lasting traditions of mutual support and village-related organization. Indeed, the federalist Francisco Pi i Margall had noticed that the anarchist movement in Spain is not the result of abstract discussions or a theory of a few intellectuals, but a result of social dynamics and developments. Spain was never strongly united at the federal level, and static Marxism seemed to be of no consequence in a regional Spain where the idea of strong central government was never strong until the rise of the extreme right.

There has been occasional, but changing, unity between anarchists and non-communist socialists, but on the whole relations have not been easy. A socialist leader once said: “There is a great deal of confusion in the minds of many comrades, you think that anarcho-syndicalism has an ideal that runs parallel to our own while taking the absolute opposing positions, and that anarchists and socialists are comrades while they are actually the greatest enemies. ”The often opportunistic UGT often aided scabs to break CNT strikes. Condemnations of socialist tactics by anarchists were by no means uncommon. In addition, the more radical socialists (like the POUM ) often forged alliances outside the anarchists, especially during the civil war and especially during the defense of Madrid. It was not until 1938 that an official unification pact was signed between the CNT and the UGT.

Communists had quite limited influence in Spain until the time of the civil war. The working classes, anarchists or not, reacted to the October Revolution with triumph, as did most revolutionaries around the world. It was hailed as a victory of the masses and a glimmer of hope. Workers refused to load weapons to be delivered to opponents of the Red Army . Anyway discovered libertarians soon the true nature of Bolschewikimacht, especially after the brutal suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion , and once again, as Leon Trotsky's Red Army, the Black Army of Nestor Makhno attacked in Ukraine. The CNT indignantly refused to join the Comintern and often criticized the policies of the Bolshevik government.

violence

Although many anarchists opposed the use of violence, some anarchists used violence to advance their agenda. This " de facto propaganda " first became popular in the late 19th century. This was before the rise of syndicalism as an anarchist tactic, and after a long history of police repression that had driven many to despair.

The Desheredados (“disinherited”) were a secret group who advocated violence and were said to be behind murders. Another group, La Mano Negra (“Black Hand”) has also been suspected of being behind various murders and bombings, although it also appears that the group name may have been a sensationalism by the Guardia Civil. Indeed, it is well known that the police invented, or even carried out, actions for their enemies as a tool of repression. Los Solidarios and the Los Amigos de Durruti (Friends of Durruti) were other groups that used violence as a political weapon. The former was responsible for a bank robbery in Bilbao that brought in 300,000 pesetas and for the assassination of Cardinal Archbishop of Saragossa, Juan Soldevilla Romero . Los Solidarios ended the use of violence with the end of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship , when anarchists had more open work opportunities because the ban on anarchist organizations was lifted.

In later years anarchists were responsible for a number of church fires across Spain. At that time the influence of the church was not as great as in the past, but the rise of anti-Christian sentiment went hand in hand with the supposed or real support of the church for right-wing and fascist forces. Many of the fires were not perpetrated by anarchists at all, but anarchists were often scapegoated by the authorities.

feminism

Feminism has historically played a role in the development of anarchism, and Spain is no exception. The founding congress of the CNT placed particular emphasis on the role of women in the labor movement and forced efforts to recruit them into the organization. There was also condemnation of the exploitation of women in society and of wives by their husbands.

Women's rights were integral parts of anarchist ideas such as co-education, the disappearance of marriage, the right to abortion among others; they were quite radical ideas in traditionally Catholic Spain. Women played an important role in many of the fights, including as comrades-in-arms with their male comrades. On the other hand, they were often portrayed as insignificant, as an example, women in the agricultural cooperatives were often paid less than men and they had less visible roles in large anarchist organizations.

The Mujeres Libres supported day care, education, maternity centers and other services for the benefit of women. The group had a membership peak between 20,000 and 38,000. Their first National Congress in 1937, with delegations from over a dozen cities representing more than 115 smaller groups. The statutes of the organization stated its purpose as “a: a conscious and responsible female force who wants to act as a guardian of progress, b: for this purpose to establish schools, institutes, reading groups, special courses, etc. to train the women and them to emancipate from the triple slavery: the slavery of ignorance / ignorance, the slavery of being a woman, and the slavery of being a worker. "

See also

- Anarchism in Germany

- Anarchism in the United States

- Anarchism in Turkey

- Anarchism in Cuba

- Anarchism in the Netherlands

literature

German speaking

- Walther L. Bernecker : Anarchism and Civil War. On the history of the social revolution in Spain 1936-1939 . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-455-09223-3 .

- Bernd Drücke , Luz Kerkeling, Martin Baxmeyer (Ed.): Abel Paz and the Spanish Revolution . Verlag Edition AV, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-936049-33-5 .

- Hans Magnus Enzensberger : The short summer of anarchy. Buenaventura Durrutis life and death . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972. ISBN 3-518-36895-8 .

- Arthur Lehning : Spanish Diary & Notes on the Revolution in Spain . edition tranvía, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-938944-04-2 .

- Felix Morrow : Revolution and Counterrevolution in Spain. Gervinus, Essen 1986, ISBN 3-88634-050-3 (Orthodox Trotskyist script).

- George Orwell : My Catalonia , Report on the Spanish Civil War . Diogenes, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-257-20214-4 .

- Abel Paz : Durruti. Life and Death of the Spanish Anarchist . Edition Nautilus, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-89401-411-3 .

- Ludwig Renn : The Spanish War . Structure, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-360-01287-9 .

- Heleno Saña : The Libertarian Revolution. The anarchists in the Spanish Civil War . Edition Nautilus, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-89401-378-8 .

- Augustin Souchy : Night over Spain. Anarcho-Syndicalists in Revolution and Civil War 1936-39. A factual report . Nevertheless, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-86569-900-8 ( Alibri ) / ISBN 978-3-922209-51-5 ( Nevertheless ).

In other languages

- Martha Ackelsberg: Free Women Of Spain. Anarchism And The Struggle For The Emancipation Of Women . ISBN 1-902593-96-0

- Robert J. Alexander: The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War . ISBN 1-85756-400-6

- Antony Beevor : The Spanish Civil War . ISBN 0-14-100148-8

- Murray Bookchin : The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years 1868-1936 . ISBN 1-873176-04-X

- Murray Bookchin: To Remember Spain ( Memento July 5, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). ISBN 1-873176-87-2

- Gerald Brenan : The Spanish Labyrinth . ISBN 0-521-39827-4

- Noam Chomsky : Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship .

- Stuart Christie : We, The Anarchists! A Study Of The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) 1927-1937 . ISBN 1-901172-06-6

- Ronald Fraser : Blood of Spain. ISBN 0-394-73854-3 .

- Miguel García: Looking Back After Twenty Years of Jail . ISBN 1-873605-03-X

- Emma Goldman : Vision on Fire. Emma Goldman on the Spanish Revolution . ISBN 0-9610348-2-3

- Agustin Guillamón: The Friends of Durruti Group 1937-1939 . ISBN 1-873176-54-6

- Hugo Oehler: Barricades in Barcelona . ( Memento from August 1, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Stanley G. Payne : The Spanish Revolution , New York: Norton, 1970.

- José Peirats: Los anarquistas en la guerra civil española . Ediciones Jucar, Madrid 1976.

- José Peirats: La CNT en la revolución Española . 3 volumes, Ediciones CNT, Buenos Aires 1952–1955.

- Elisabeth de Sotelo: Feminist theory and feminist movement in Spain , 2006.

- Josep Termes: Historia del anarquismo en España (1870–1980) . RBA Libros, Barcelona 2011.

Movies

- Juan A. Gamero Vivir la Utopia Arte-TV, 1997 . The film about anarchism in Spain with 30 surviving anarchists of the Spanish Revolution and the civil war was shown on German television on Arte under the title: " Live the utopia! Anarchism in Spain. "

- The Anarchist's Wife is a German-Spanish-French film drama of directors Marie Noëlle and Peter Sehr from the year 2008 .

- Libertarias (Freedom Fighters) by Vicente Aranda , Spain 1996. Spanish fictional film with English subtitles, fictional to the Mujeres Libres .

Web links

- The Spanish Revolution, 1936–39 Articles & Links, from "Anarchy Now"

- The role of anarchism in the Spanish Revolution - civil war resource

- Walther L. Berneker: Lecture on anarcho-syndicalism in Spain

- Augustin Souchy: The Social Revolution in Spain 1936

- 70 years of the Spanish Revolution. Main focus of the anarchist monthly Graswurzelrevolution (GWR 310 f., Summer 2006)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Max Nettlau: Bakunin and the International in Spain 1868–1873 , in: Archives for the history of socialism and the workers' movement 4 (1914) 243-303 , here: p. 264

- ↑ Wolfgang Eckhardt (Ed.): Michael Bakunin. Conflict with Marx. Part II: Texts and letters from 1871 onwards. Karin Kramer Verlag, Berlin 2011, p. 409.

- ↑ Nettlau, Max : Anarchists and Social Revolutionaries . ASY-Verlag, Berlin 1931, p. 289.

- ↑ cf. J. Romero Maura: Terrorism in Barcelona and Its Impact on Spanish Politics 1904-1909 . In: Past and Present, No. 41 (Dec. 1968), Oxford, pp. 130-183.

- ↑ Max Nettlau : The first heyday of anarchy: 1886-1894 . Topos Verlag, Vaduz 1981, p. 335ff.

- ↑ Max Nettlau : The first heyday of anarchy: 1886-1894 . Topos Verlag, Vaduz 1981, p. 343.

- ^ Murray Bookchin : After Fifty Years: The Spanish Civil War

- ↑ The English writer Ralph Bates witnessed the struggle of the anarchist workers against the military in Barcelona. His report was published on October 13, 1936 in the British magazine "Left Review". (German: Ralph Bates: Compañero Sagasta burns down a church. Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-945831-09-0 , pp. 37–51)

- ↑ Dolores Ibárruri: Memorias de Dolores Ibárruri , p. 382.

- ↑ George Orwell : My Catalonia (1938). Eighth chapter.

- ^ Walther L. Bernecker: War in Spain 1936–1939 . Darmstadt 2005, p. 167.

- ↑ Heleno Saña : The Libertarian Revolution. The anarchists in the Spanish Civil War . Nautilus, ISBN 3-89401-378-8 , p. 129.

- ^ Albert Meltzer [1996]: XIII . In: I Couldn't Paint Golden Angels . AK Press, Edinburgh, pp. 200-201, ISBN 1-873176-93-7 .

- ^ The Spanish CGT - The New Anarcho-syndicalism. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014 ; Retrieved August 28, 2006 .