Anarchism in Cuba

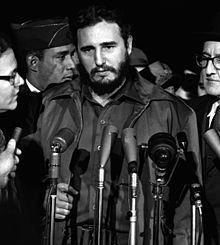

The anarchism in Cuba had as a social movement a great impact on the Cuban working class in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement was particularly strong after the abolition of slavery in 1886, until the movement was suppressed by President Gerardo Machado and finally crushed by Fidel Castro's Marxist-Leninist government after the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s. Cuban anarchism was primarily collectivist and later strongly influenced by anarcho-syndicalism . In general, the Latin American labor movement, especially the Cuban movement, was initially more influenced by anarchism than Marxism.

history

Colonial times

In the middle of the 19th century, Cuba was shaped by three social classes: the Spanish-born criollos made up the ruling class of tobacco, sugar cane and coffee plantation owners, the middle class consisted of black and Spanish plantation workers, and at the bottom of the hierarchy were the slaves. There were also great differences between the Creoles and the Spaniards (also called peninsulares ), as the native Spaniards benefited greatly from the colonial regime . Cuba was a Spanish colony, but there were also aspirations for independence, as well as movements for the integration of Cuba into the United States or Spain.

In 1857, based on the model of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a mutualistic society was founded, which is considered the first expression of anarchism in Cuba. Saturnino Martínez, an Asturian immigrant, founded La Aurora magazine in 1865 after he was introduced to Proudhon's ideas by José de Jesus Marquez. This sheet, which was mainly aimed at tobacco workers, contained the very first calls for the establishment of proudhonist cooperative societies in Cuba. Exiles from the Paris Commune also fought for independence among the insurgents in the Ten Years War, and important figures such as Salvador Cisneros Betancourt and Vicente García González were influenced by Proudhon.

Early movement development

In the 1880s, José C. Campos made contact with Spanish anarchists from Barcelona and imported anarchist literature and magazines. At the same time, many Spanish anarchists emigrated to Cuba. It became common for workers in the tobacco factories to read anarchist literature aloud, which did much to spread anarchist ideas. During the 1880s to the early 1890s, the Cuban anarchists oriented themselves towards collectivist anarchism and took the Spanish Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española (German: Workers' Federation of the Region of Spain ) as a model. Instead of the communist anarchists ' slogan “each according to his abilities, each according to his needs” , the Cuban anarchists took the position that in a future anarchist society every person should receive common goods according to the work he has done.

In 1882 Enrique Roig San Martín founded the Centro de Instrucción y Recreo de Santiago de Las Vegas (English: Center for Education and Recreation of Santiago de Las Vegas ), where the self-organization of the workers was promoted and literature by the Spanish collectivist anarchists was made available . The center had the strict principle of accepting all Cubans "regardless of their social position, political orientation, or skin color." In the same year, the Junta Central de Artesanos (German: Central Council of Craftsmen ) was founded with the intention of Roig San Martín stated that “no professional association and no workers 'organization should be tied to the feet of the capital.” Roig San Martín wrote for the magazine El Boletín del Gremio de Obreros (German: The newspaper of the workers' council ) and for the first explicitly anarchist newspaper El Obrero (Eng .: the worker ). It was originally founded by Democratic Republicans in 1883, but quickly changed direction after Roig San Martín took over the editorial office. Roig San Martín then founded the newspaper El Productor (Eng .: The Producer ) in 1887 . In addition to Roig San Martín, El Productor had several authors in the Cuban cities of Santiago de Las Vegas and Guanabacoa , and in the cities of Tampa and Key West in Florida . In addition, numerous articles appeared from the French-language anarchist magazine Le Révolté and the magazine La Acracia from Barcelona.

In 1885, the Círculo de Trabajadores (German: Workers' Circle ) was founded, an organization that dealt with educational and cultural activities. This also included the establishment of a secular school in which 500 pupils from poor families received an education and where groups of workers also held their meetings. The following year, the leaders of the Círculo (headed by Enrique Creci) formed an auxiliary committee that raised funds for the eight Chicago anarchists arrested in connection with the Haymarket Riot . In a month and a half, the committee raised about $ 1,500 for this purpose. In addition, a few days before the Chicago anarchists were executed , the Círculo organized a demonstration of around 2,000 people in Havana to protest the verdict. The Círculo and El Productor were both subsequently fined by the Cuban state; the newspaper, for an editorial by Roig San Martín about the executions, and the Círculo for having a painting displayed to commemorate the executions. The colonial government also banned the demonstrations held each year in memory of the Chicago anarchists.

Gaining strength of the anarchist movement

The first explicitly anarchist organization Alianza Obrera (German: Workers' Alliance ) was founded in 1887. The organization took part in the first Congreso Obrero de Cuba (English: Cuban Workers' Congress), which took place on October 1, 1887 , together with the Federacíon de Trabajadores de la Habana (German: Havana Labor Union ) and the group around El Productor . Most of the Congress was attended by tobacco workers, but not exclusively. The congress agreed on six congressional resolutions: resistance to all forms of authority, unity of the workers 'organizations through a common federation, complete freedom of action of the affiliated groups, cooperation and solidarity of the groups and a ban on all political and religious doctrine among the affiliated workers' groups. Saturnino Martínez was disappointed with the outcome of the congress, where reformist positions prevailed. This led to a conflict between Martínez and Roig San Martín and two rival camps formed.

Shortly after Congress, tobacco workers went on strike at three factories, one of which continued through November. Later, in the summer of 1888, workers were locked out by factory owners during strikes in more than 100 factories . The Círculo de Trabajadores collected donations to support the striking workers in a large campaign and even sent representatives to Key West to raise money from American tobacco workers. In October the factory owners ended the lockout of the workers and they agreed on joint negotiations. The outcome of the labor dispute was very successful for the Alianza Obrera , so that the number of members rose from 3,000 to 5,000 in the next six months, making the Círculo the strongest union in Cuba. The following year, Roig San Martín died at the age of 46, just days after his release from prison of the Spanish colonial government; 10,000 people attended his funeral. Just a few months later, the head of the colonial government, Manuel Salamanca y Negrete , banned the Alianza Obrera and the Círculo de Trabajadores in response to the strikes in the tobacco industry . The four schools that the Círculo de Trabajadores ran were not affected by the ban and the Círculo as a whole was re-approved as an organization by the new government the following year.

Repressive measures by the government and the war of independence

In 1890, May Day was celebrated for the first time in a large rally in Cuba . After the demonstration, the participants met for an event with lectures by 18 anarchists. In the days that followed, Cuban workers in various industries went on strike. The colonial government reacted again by banning the Círculo de Trabajadores . However, it reversed this decision a short time later after 2,300 workers protested against this decision in a letter. In the same year, eleven anarchists were suspected of being involved in the murder of Menéndez Areces, a union official of the moderate Uníon Obrera (German: workers' union ). However, the court found that all eleven anarchists were innocent. Captain-General Camilo García de Polavieja y del Castillo, however, used the process as an excuse to stop the publication of El Productor magazine and to increase the repression against anarchists in general. Another workers' congress was held in 1892, confirming anarcho-syndicalist principles and expressing solidarity with working women (a new attitude in the male-dominated working class, where men mostly saw working women as competition). The congress made the following statement: “It is an urgent duty not to forget the women, who are now increasingly beginning to pour into the workshops of various industries. They are forced to compete with us by the need and the civic greed of the entrepreneurs. We cannot prevent that; let us help you. ”The government responded to the workers' congress with repression against the anarchist movement through deportation, imprisonment, the lifting of freedom of assembly and the closure of the organization's headquarters.

During the Cuban War of Independence , the Cuban anarchists distributed propaganda material to the Spanish soldiers urging them not to oppose the separatists and to join the anarchists. A few years earlier, the anarchists in Cuba had adopted the fighting method of the Spanish anarchists, who not only organized themselves in the trade union, but also formed small fighting groups at the same time, did educational work and also used violence to resist the state. The Cuban anarchists were responsible for blowing up several bridges, sabotaging gas pipes and in 1896 they also took part in the separatists' attempt to assassinate the head of the colonial regime, Captain-General Valeriano Weyler . This led to further repression against the anarchists, the closure of the Sociedad General de Trabajadores (which grew out of the Círculo ), mass deportations of activists and even the prohibition of lectura , reading of newspapers etc. for workers while at work.

Early 20th century

After the Spanish-American War , which brought Cuba independence from Spain, many anarchists were dissatisfied with the situation in Cuba. The reason for this was that the new government was repeating the mistakes of the old colonial government. The labor movement continued to be suppressed, the country was under US occupation and the school system barely improved. In 1899 the anarchist workers organized themselves again in the Alianza de Trabajadores (German: Workers' Alliance ). In September of that year, five key members were arrested after a bricklayer strike spread across the construction industry. During this time, the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta also visited Cuba. He lectured and gave interviews for various newspapers until the government stepped in and prevented further speeches. In 1902/03, anarchists and other trade unionists attempted to unionize workers in the sugar industry, at that time Cuba's largest industry. The sugar manufacturers reacted quickly to these attempts and two workers were subsequently murdered. The murders were never solved.

Anarchist activists turned their main focus more and more on preparing society for a great social revolution. They organized schools for children that were an alternative to the Catholic and public schools. The anarchists believed that religious schools were hostile to free thinking and that public schools were too often used to indoctrinate children with patriotic nationalism and to nip children's free thinking in the bud. In ¡Tierra! , an anarchist weekly newspaper published from 1899 to 1915, the authors condemned public schools for forcing children to oath the oath and encouraged teachers to show children that the flag was a symbol of "bigotry and discord." . At the same time, they saw the children of these schools as "cannon fodder" for the conflict between the Liberal and Conservative party leaders in 1906 that led the United States to occupy Cuba by 1909. Although anarchists had been organizing schools since the time of the Círculo de Trabajadores , these schools were more traditional until around 1906. In 1908, anarchists published in the editions of ¡Tierra! and La Voz del Dependiente, a manifesto in which they called for schools to be formed that corresponded to Francesc Ferrer's model of the Escuela Moderna (Eng .: Modern School ).

Repression and union activity

In 1911 an unsuccessful strike by tobacco workers, bakers and truck drivers took place, which was reported by the anarchist magazine ¡Tierra! was supported. Gerardo Machado , who was State Secretary at the time, arranged the deportation of many Spanish anarchists and the arrest of Cuban anarchists. This line of strong government repression against anarchists, which was decided at this time, was continued for the next 20 years. After García Menocal gained control of the Cuban government in 1917, the government responded to several general strikes with violence. Several anarchist organizers were killed, including Robustiano Fernández and Luis Díaz Blanco. Some anarchists then responded with violent actions. A group of 77 anarchists, which the government called "anarcho-syndicalist mob", was deported to Spain. Anarchist magazines were also banned ( ¡Tierra! Was discontinued in 1915) and the anarchist Centro Obrero (workers' center) was forced to close. After the anarchist congress of Havana in 1920, a number of bombings took place, including a bomb attack on the Teatro Nacional . In the following year Menocal lost government power to Alfredo Zayas y Alfonso , which again allowed for greater activity by anarchist groups. The ¡Tierra! began publishing books and pamphlets, and at least six other regular anarchist magazines appeared.

At the time, the anarcho-syndicalists were the strongest and most active part of the Cuban labor movement. However, it was not until 1925 that a national anarchist federation was established, although workers in the maritime, rail, catering and tobacco sectors were already largely organized by anarchist trade unionists. In the same year there was a similar development in the Cuban anarchist movement as in Spain in the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo , where a part of non-anarchist members of the Confederación Nacional Obrera Cubana (German: Cuban National Workers' Federation ) founded the Communist Party of Cuba . At that time, many anarchists were enthusiastic about the October Revolution (including Alfredo López and Carlos Baliño ) and increasingly represented authoritarian forms of organization. Many strikes took place in the autumn of 1925 and the government, which was again under Machado's leadership, resorted to repressive measures against the labor movement. Several labor leaders were shot and several hundred Spanish anarchists were deported within a month. Machado stated, “You are right, I don't know what anarchism is, what socialism is and what communism is. They are all the same to me. Bad patriots. ”Alfredo López, then General Secretary of the Confederación Nacional Obrera Cubana , was first arrested in October 1925 and encouraged to join the government. After another arrest in July 1926, Alfredo López disappeared. His body was only found again in 1933 after the fall of Machado's dictatorship.

Reorganization after López's disappearance and the deportation of the Spanish anarchists

After the disappearance of López, there was a fight between anarchists and communists over the direction of the Confederación Nacional Obrera Cubana . In 1930/31 the communists finally succeeded in taking control of the CNOC . The anarchists were handed over to the police, which were still under Machado's control. Many of the Spanish anarchists then decided to return to Spain. This was compounded after the new government passed a law requiring entrepreneurs to employ at least half of their employees who were born in Cuba. As a result, many Spaniards had to leave Cuba for economic reasons, which further weakened the influence of the anarchist movement in Cuba. Nevertheless, shortly afterwards younger anarchists founded the Juventud Libertaria (Eng .: Libertarian Youth ). In 1936, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War , the Cuban anarchists founded the Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista to provide financial support to the anarcho-syndicalist union CNT and the FAI in Spain. Many Cuban anarchists went to Spain with Spanish anarchists who were expelled from Cuba and took part in the war against Francisco Franco .

With the Cuban constitution of 1940 certain rights were guaranteed and anarchists were able to organize themselves more undisturbed, since the probability of a policy of violent repression was lower. The Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista and the Federacíon de Grupos Anarquistas de Cuba disbanded and their several thousand members founded the Asociacíon Libertaria de Cuba (German: Libertarian Association of Cuba ). The ALC held its first national congress in 1944, at which a general secretary and an organizational secretary were elected. A second congress followed in 1948, at which Augustin Souchy gave the opening speech. Solidaridad Gastronómica was chosen as the official propaganda organ and appeared monthly until December 1960, when it was banned by Fidel Castro's government. The third congress was held in 1950. The main topic was how to keep the labor movement away from electoral politics and how to counter the influence of politicians and bureaucrats on the labor movement. In the mid-1950s, Fulgencio Batista came to power again after a successful coup and ruled the country dictatorially. Many anarchists joined the guerrilla groups fighting Batista, including Fidel Castro's July 26th Movement, which forced Batista to flee Cuba on the last day of 1958. A key figure in the July 26th Movement was Camilo Cienfuegos , a former anarchist from a Spanish family who fled the civil war.

After the Cuban Revolution

1960-1961

In the first days after he came to power, Fidel Castro excluded well-known anarcho-syndicalists from the Confederacíon de Trabajadores de Cuba (German: Cuban Workers' Federation ). The anarcho-syndicalist Asociacíon Libertaria de Cuba responded with a public statement in which they sharply criticized the Castro government. Authors in the magazine Solidaridad Gastronómica also expressed their displeasure with Castro and wrote that it was impossible for a government to be "revolutionary". In January 1960, the ALC called a meeting and proclaimed support for the Cuban Revolution, while at the same time calling itself an opponent of totalitarianism and dictatorship. At the end of the year the Solidaridad Gastronómica magazine was banned by the government. The last edition was published in memory of the death of the Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti . It contained an editorial stating that the dictatorship of the proletariat was impossible and that no dictatorship could originate from the proletariat, on the contrary, the proletariat would always be ruled.

In the summer of 1960, the German anarchist Augustin Souchy was invited by the Castro government to write a study on the agricultural sector. Souchy was anything but impressed with what he found in Cuba and stated in his report Testimonios sobre la Revolución Cubana (Eng .: testimony about the Cuban revolution ) that the system was oriented too closely to the Soviet model. Three days after Souchy left Cuba, all printing was confiscated and destroyed by the government. Yet an anarchist editor published Souchy's report the following December in Argentina. At about the same time, the ALC reacted as it was concerned about the policies of Castro's government, which were moving more and more towards a dictatorship with a Marxist-Leninist character. The ALC published a statement against the Castro government, which it issued under the name Grupo de Sindicalistas Libertarios to protect members of the ALC from repressive measures. In this document, the anarchists declared themselves to be opponents of the centralism, authoritarian tendencies and militarism of the new government. The General Secretary of the Partido Comunista Cubano (PCC) criticized the authors in a reply. The anarchists could not counter this attack, however, because they could not find a printer for another letter that would print the text. The last issue of El Libertario magazine appeared in the summer of 1961.

After these events, many anarchists opted for the underground and a direct action tactic . According to the Cuban anarchist Casto Moscú, “Countless public statements were written criticizing Castro's wrongdoing and calling on the population to resist. Plans have been carried out to target the sabotage of essentials for the survival of the state. ”Manuel Gaona Sousa, one of the founders of the ALC and a former anarchist, then issued a statement expressing support for the government and called all opponents of the government "traitors". As a result, the anarchists Casto Moscú and Manuel González were arrested in Havana. After their release, both went to Miami via Mexico , where they met many of their Cuban colleagues.

exile

From the mid-1960s, but especially in the summer of 1961, many Cuban anarchists emigrated to the United States. In the summer of 1961, the Movimiento Libertario Cubano en el Exilio (MLCE; German: Anarchist Movement of Cuba in Exile ) was founded by Cubans in exile in New York . The organization contacted the Spanish anarchists who emigrated to New York after the end of the Spanish Civil War. The organization also contacted the American anarcho-syndicalist Sam Dolgoff and the New York Libertarian League . Donations from various countries for the Cubans in exile quickly came together. This solidarity was short-lived, however, because in 1961, with the help of the Castro government, the so-called Gaona Manifesto was sent to anarchist groups all over the world, the majority of whom received the document positively. The document, which appeared on behalf of the Asociacíon Libertaria de Cuba and was written by the former anarchist Manuel Gaona, made an official impression and supported the Castro government. In response to the great impact of the manifesto, the MLCE issued the Boletín de Información Libertaria . She was supported by the Libertarian League and the Federación Libertaria Argentina (FLA). Among other things, the FLA printed a work by Abelardo Iglesias entitled Revolución y Contrarevolución . In it Iglesias pointed out the differences that Cuban anarchists saw between a Marxist and an anarchist revolution: “Expropriating capitalist companies and handing them over to the workers, THAT'S REVOLUTION. However, to transform the companies into state monopolies, in which every worker just has to obey, THAT'S COUNTER REVOLUTION. "

While the Cubans in exile in the US were trying to raise money for the captured anarchists in Cuba, they were seen by the anarchists in the United States and other countries as puppets of the CIA and as mere anti-communists . The American anarcho-pacifist magazine Liberation printed Castro-friendly articles, which the anarchist Cuban exile and their organization MLCE responded with a demonstration in front of the magazine's editorial office. In 1965 the MLCE sent Abelardo Iglesias to Italy to explain to the Federazione Anarchica Italiana its fight against the Castro regime. The Italian anarchists were won over and published articles condemning the Cuban regime. The articles appeared in various Italian anarchist magazines, such as Umanità Nova , and signatures were collected from solidarity organizations in different countries, including the Federación Libertaria Argentina , the Federación Libertaria Mexicana , the Anarchist Federation of London , the Sveriges Arbetares Central Organization , the French Fédération anarchiste , and the Movimiento Libertario Español .

The hostility of many anarchist groups towards the MLCE and the Cubans in exile did not begin to change until 1976 after the publication of Sam Dolgoff's book The Cuban Revolution: A Critical Perspective ( Eng .: The Cuban Revolution: A Critical Perspective ). 1979 MLCE began the publication of a new magazine called Guángara Libertaria where Alfredo Gómez 'article The Cuban Anarchists, or the Bad Conscience of Anarchism (dt .: The Cuban anarchists, or the bad conscience of anarchism was re-printed). In 1980 the MLCE and the Guángara Libertaria supported the mass emigration of Cubans to the United States after many Cuban dissidents occupied the Peruvian Embassy in Havana. Many of the newcomers joined the editorial team of Guángara Libertaria . By 1985, the editorial collective had correspondents in many places including Mexico, Hawaii, Spain and Venezuela. The magazine reached 5,000 copies in 1987, making it the top-selling anarchist newspaper in the United States at the time. However, in 1992 the publication of Guángara Libertaria was stopped, but many former members of the editorial board continued their publishing activities. In 2008 the MLCE was organized as an Affinity Group , open to Cuban anarchists of various currents.

See also

- Anarchism in Spain . Anarchism in Germany . Anarchism in Turkey . Anarchism in the United States . Anarchism in the Netherlands .

literature

- Herbert L. Matthews: Revolution in Cuba . Charles Scribner's Sons , New York 1975, ISBN 978-0-684-14213-5

- Joan Casanovas: Bread Or Bullets: Urban Labor and Spanish Colonialism in Cuba, 1850–1898 . University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh 1998, ISBN 978-0-8229-5675-4

- Frank Fernández : Cuban Anarchism: The History of a Movement . See Sharp Press 2001, ISBN 978-1-884365-19-5

- Frank Fernández: Anarchism in Cuba. the story of a movement. Syndikat-A, Anarcho-Syndikalistischer Medienvertrieb, Moers 2006. ISBN 3-9810846-3-2 . Available online. German translation of the book.

- Hugh Thomas: Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom . Da Capo Press 1971.

- Hilda Barrio / Gareth Jenkins: The Che Handbook . St. Martin's Press 2003, ISBN 0-312-32246-1

-

Max Nettlau (Ed.): History of Anarchy. In collaboration with the International Institute for Social History (IISG, Amsterdam). Newly published by Heiner Becker. Library Thélème, Münster 1993, 1st edition, reprint of the Berlin edition, Verlag Der Syndikalist , 1927.

- Volume 6–7 Anarchists and Syndicalists Part 2. ChapterXIII. “Anarchist activity and movements in the non-European Spanish-speaking area. Overview of these countries. Cuba, Florida, the rest of the United States, and the Canal Zone (Panama). Adrian del Valle. Pedro Esteve. "

- Sam Dolgoff: Beacon in the Caribbean. A libertarian view of the Cuban revolution. Libertad Verlag , Berlin 1983. ISBN 978-3-922226-07-9

- Augustin Souchy: The Cuban Libertarios and the Castro Dictatorship. In: Akratie Nr. 4, 1975 available online .at www. anarchismus.at

Web links

- Three articles by Kirwin R. Shaffer on anarchism in Cuba:

- Freedom Teaching: Anarchism and Education in Early Republican Cuba, 1898–1925 . In: The Americas . October 2003, 60, No. 2, pp. 151-183.

- Anarchism and Countercultural Politics in Early Twentieth-Century Cuba.

- Women and Anarchism in Cuba. (PDF; 197 kB)

- Sam Dolgoff: The Cuban Revolution .

- Website of the Libertarian Movement of Cuba (Movimiento Libertario Cubano)

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert L. Matthews: Revolution in Cuba . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1975, p. 223

- ↑ Sam Dolgoff: The Cuban Revolution: A Critical Perspective ( Memento June 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). Black Rose Books, Montréal 1977, p. 1. ISBN 0-919618-36-7

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Joan Casanovas: Bread, or Bullets !: urban labor and Spanish colonialism in Cuba, 1850-1898 . University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh 1998.

- ^ Robert Graham: Enrique Roig de San Martin - The Motherland and the Workers (1889)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Frank Fernández : Cuban Anarchism: The History of a Movement ( Memento from February 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 2.08 MB) , See Sharp Press.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Hugh Thomas: Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom. Da Capo Press, 1971.

- ^ A b c Kirwin R. Shaffer: Freedom Teaching: Anarchism and Education in Early Republican Cuba. 1898-1925. In: The Americas , Oct. 2003, pp. 151-183.

- ↑ Cuban Anarchism and Camilo Cienfuegos' 50th Anniversary of Death (2009)

- ↑ Hilda Barrio / Gareth Jenkins: The Che Handbook . St. Martin's Press 2003, p. 132.

- ^ Frank Fernández: Cuban Anarchism: The History of a Movement . See Sharp Press 2001, p. 101.

- ^ ALB interviews the Cuban Libertarian Movement . In: A Las Barricadas . Infoshop.org. July 16, 2008. Archived from the original on July 16, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.