Buenaventura Durruti

Buenaventura Durruti Dumange (born July 14, 1896 in León , † November 20, 1936 in Madrid ) was a Spanish anarchist , syndicalist and revolutionary . As the elected leader of an elite republican column, he was one of the central figures in the Spanish Civil War .

Life

Early years

Buenaventura Durruti was born in the old episcopal city of León. His father and seven brothers were railroad workers . He was a gifted student, attended the Capuchin Sunday school and received various awards. At the age of 14 he began to work as a mechanic and caster. From 1910 to 1911 he worked in the workshop of Melchor Martinez and received an hourly wage of 25 centimos as a locksmith; he also attended evening school.

From 1911 to 1916 he worked in Antonio Miaja's foundry, where he met workers from Asturias. Durruti joined the Socialist Trade Union ruled by Social Democrats.

General strike in Spain and first exile

In 1916 he joined the northern Spanish railway company as an apprentice mechanic on probation. In 1917 he took part in the strike of the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT). The industrial action had been fierce on both sides; Union militants had carried out acts of sabotage and the Spanish army eventually put down the strike. As a result, Durruti and many other strikers were fired. In the mining district of Asturias he now joined the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and recruited new members. However, since Asturias was a stronghold of the Social Democratic union, Durruti was blacklisted. Since Durruti also wanted to evade military service , he went to France and stayed in Paris until 1920 , where he maintained contact with anarcho-syndicalists .

Return to Spain

In 1920 Durruti returned to Spain and joined anarchist combat groups in San Sebastian . There he also met Francisco Ascaso , Juan García Oliver and Gregorio Jover , who became his closest comrades. However, Durruti was arrested in San Sebastian and drafted into military service; assigned to the fortress artillery, he suffered a hernia and was dismissed as unfit.

The political climate in Barcelona had worsened since 1917. The so-called urban guerrilla was formed and Durruti also became a fighter in a workers' self-defense corps, as around 33 anarcho-syndicalists had been killed in Barcelona by the other side. In response to these acts of violence, Durruti is said to have been involved in numerous assassinations, in particular in the murder of the Archbishop of Saragossa, Cardinal Juan Soldevila y Romero on June 4, 1923 .

In 1922 Durruti and Ascaso founded an ideological alliance. They called themselves Los Justicerioes (Spanish: The Righteous) and thus became the forerunners of the Los Solidarios (Spanish: The Solidarians).

Second exile and international activities

In 1921 Prime Minister Eduardo Dato was assassinated, which led to the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera from 1923 onwards . Together with some comrades Durruti went into exile again . He first settled in Paris, where he worked as a locksmith at Renault .

But not only in Spain, but also in France and South America, Durruti was now wanted because of subversive activities. In 1924 he embarked with Ascaso for Cuba , where he stood up as a public speaker for the revolution in Spain. When the authorities found out, he had to flee to Europe and ended up in prison in Paris. In 1927 he met his partner Émilienne Morin . They lived together until his death. Their daughter Colette was born on December 4, 1931.

In 1928 Durruti was expelled from Germany after a short stay , where he met the German anarchist Augustin Souchy together with Ascaso and Jover in Berlin and lived with him for several weeks at Augustastraße 62 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf . In 1930 he was granted a residence permit in Belgium , where he could live in relative peace for two years. Meanwhile, the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed and the anarcho-syndicalist trade union federation CNT was instantly reformed.

Second return to Spain

Durruti went back to Spain and took part in a leading uprising in the Alto Llobregat in January 1932 . After this failed, he was taken into preventive detention by the central government and deported to Fuerteventura together with other comrades on February 10, 1932 . At the end of August of the same year he was able to return to Barcelona after a general strike by the CNT.

There followed a period of numerous strikes and uprisings, during the course of which there were already major differences with the socialists and Marxist communists. The CNT now appeared together with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Durruti was considered to be the head of the FAI, which condemned and sharply attacked the legalistic course of the CNT leadership under Macia. In 1936 the left won the elections in Spain, and insurgent troops left the barracks all over Spain. In Barcelona there was an armed struggle, the victory of the CNT-FAI and the first and only anarcho-syndicalist self-government of a political region in Europe.

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War followed. Durruti became the organizer and commander of an anarchist militia, the Durruti column , which fought in Aragon and tried in vain to conquer the city of Zaragoza , which was occupied by the nationalists . In the course of the civil war, the anarchists were pushed more and more against the wall - not only by the Francoist opponents, but above all by the communists, who also fought against Franco. The Comintern policy followed by the Spanish communists in the sense of Stalinism ( socialism in one country ) at that time primarily aimed at safeguarding the foreign policy interests of the Soviet Union. In the Spanish Civil War, these interests included, above all, the protection of the Western powers, which were heavily involved in financial matters in Catalonia, from expropriation, as the anarchists sought. Federica Montseny , Minister of Health at the CNT, said: “We were in a terrible position, we were completely cornered. Through the arms aid of the Soviet Union, the communists had gained tremendous influence. We constantly had to fear that the Spanish anarchists would face a similar fate as the anarchists in Russia once did. "

The influence of the CP increased day by day, although it had never taken root in the Spanish proletariat; Soviet commissioners and agents appeared in Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona and took on advisory functions in the military and police apparatus. “ Stalin treated the Spanish Revolution like a pawn. He made them an object of Soviet foreign policy, ”wrote Hanns-Erich Kaminski .

Durruti's death

On November 19, 1936, Durruti was hit by a bullet during the siege of Madrid and died from his injuries on November 20. There are numerous rumors surrounding his death. From the fascists to the communists to the Amigos de Durruti and Durruti's closest friends, there were conjectures as to who was responsible for Durruti's death. Shortly before his own execution as a “Trotskyist”, Mikhail Kolzov had published one of his usual idiosyncratic columns about the death of Durruti in Pravda , where it was rumored that Durruti had defected to the communists. The German Antonia Stern linked Durruti's death with the death of Hans Beimler , the commander of the Thälmann battalion , who, according to Stern, was killed by his Russian military advisor; that would have been Santi in Durruti's case.

Durruti was fatally injured in Madrid when he was shot in the lungs while getting out of a vehicle or after getting out of the vehicle. He died a day later in the Hotel "Ritz" in Madrid, which was then used as a hospital. It was regularly suggested that the fatal shot had been fired from a greater distance. Abel Paz believes that there was shooting from the nearby university hospital, which was in the hands of the nationalists. The coroners who examined Durruti's shirt, which he was wearing at the time of the crime, a year later, came to the conclusion that the shot had been fired from a distance of no more than ten centimeters. According to alleged eyewitness Ramón Garcia López, Durruti self-inflicted the fatal injury when a shot went off while getting out of his own gun. Durruti's weapon, a Naranjero - an MP28 recreated in Valencia - was known for its sensitivity to locking and unloading.

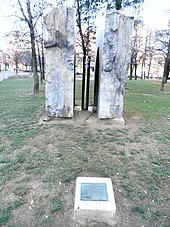

He was transported all over Spain and buried on the Cementiri de Montjuïc . Around 500,000 people took part in the funeral procession in Barcelona. The writer Carl Einstein , militiaman in the Durruti column, gave a commemorative speech on the radio at the funeral of his comrade, as he calls Durruti.

estate

In the Spanish civil war, a right-wing coalition made up of fascists , monarchists and other groups prevailed and led to the so-called Franco dictatorship , which lasted until 1975. After Durruti's funeral, his body disappeared from its grave under unexplained circumstances.

Durruti's biographer was Abel Paz , born in Almería in 1921, whose real name was Diego Camacho. He wrote the standard work Durruti. Life and Death of the Spanish Anarchist .

Quotes

“It is us who built these cities and palaces - here in Spain and in America and everywhere. We workers can erect other cities and palaces in their place. And even better ones. We are not in the least afraid of the rubble. We will be the heirs of this earth ... here in our hearts, we carry a new world. Now, at this moment, this world is growing. "

Movie

- Buenaventura Durruti - Biography of a Legend - A film novel by Hans Magnus Enzensberger (book, direction, production). WDR, Germany 1972. 92 minutes b / w. The film was shot in 1971 by a small team around HM Enzensberger in the Netherlands, Spain and France. It is a montage of contemporary recordings, eyewitness reports and pictures that try to trace the personality of this probably best-known Spanish anarchist worker activist. The film deals with four themes: 1. epistemological difficulties about historical processes; 2. the question of the formation of political legends; 3. dealing with the manifestations of anarchism; 4. the problem of the aging of the revolution.

- Buenaventura Durruti, anarchist (Original: Vida y Muertes de Buenaventura Durruti, Anarquista ) by Jean-Louis Comolli / Ginette Lavigne. Arte, France / Spain 1999. 107 minutes. Also ran on German television on Arte. The black and red thread of the film is made up of test works by the Spanish group Els Joglars, who try to capture the life, enthusiasm, ideas and deeds of Durruti, Ascaso and Garcia Oliver and the anarchist movement, the CNT-FAI, using photos and archive recordings and to empathize with texts and bring them to life.

- Durruti in the Spanish Revolution by Paco Rios and Abel Paz . 55 minutes, production: Fundacion Anselmo Lorenzo, Spain 1998. German version of the film by FAU-Leipzig. Using original documents, the film traces the life of the metalworker and anarchist Buenaventura Durruti. Not only Durruti himself has a say, but also his partner Emilienne Morin and numerous other contemporaries. The film offers a stimulating insight into the revolutionary events in Spain of 1936.

- Vivir la Utopia (Living utopia) Jose A. Gamero, Arte-TVE 1997. 96 minutes. Historical images and 30 anarchists tell in interviews about the development of anarchism up to 1936/1939, Durruti appears in passing.

literature

- Miguel Amorós : La Revolución traicionada. La verdadera historia de Balius y los Amigos de Durruti. Virus editorial, Barcelona 2003, ISBN 84-96044-15-7 .

- Bernd Drücke , Luz Kerkeling, Martin Baxmeyer (Ed.): Abel Paz and the Spanish Revolution Interviews and lectures. Edition AV , Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-936049-33-5 .

- Carl Einstein : The Durruti column. Radio address in November 1936. In: Carl Einstein: Works. Volume 3: 1929-1940. Berlin edition. Fannei & Walz, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-927574-21-X , pp. 520-524.

- Hans Magnus Enzensberger : The short summer of anarchy. Buenaventura Durrutis Life and Death (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch 395). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-518-36895-8 .

- Simone Weil 1960 (Ed.): Ecrits historiques and politiques Paris 1960.

- Free Workers' Union Bremen (ed.): The CNT as a vanguard of international anarcho-syndicalism. The Spanish Revolution 1936. Reviews and biographies. Edition AV, Lich 2006, ISBN 3-936049-69-6 .

- Hanns-Erich Kaminski : Barcelona. One day and its consequences. 2nd Edition. edition tranvía - Verlag Walter Frey, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-925867-74-0 .

- Abel Paz : Durruti. Life and Death of the Spanish Anarchist. 3. Edition. Edition Nautilus , Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-89401-411-3 .

- Abel Paz (Ed.): Durruti. 1896-1936. Edition Nautilus et al., Hamburg et al. 1996, ISBN 3-89401-267-6 .

- Heleno Saña : The Libertarian Revolution. The anarchists in the Spanish Civil War. Edition Nautilus, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-89401-378-8 .

- Durruti's cook. Notes from the time of the Spanish Civil War , translated by Ambros Waibel , Ventil, Mainz, 2017, ISBN 978-3-95575-060-2 .

- Francisco Álvarez: Durruti - The new world in our hearts , translated from the Spanish by Manfred Gmeiner, Bahoe Books , Vienna 2020.

Web links

- Literature by and about Buenaventura Durruti in the catalog of the German National Library

- Buenaventura Durruti, Libertarian Communist Militant of Spain Information on Durruti (English)

- Buenaventura Durruti (Leon 1896 - Madrid 1936) biography on anarchismus.at

- Buenaventura Durruti, Anarquista Information about the film project with Els Joglars (1999) (Spanish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Abel Paz, Durruti ; After: Andreas Fanizadeh : On the death of Abel Paz. Revolutionary against Stalinists ; in: taz, edition of April 17, 2009. [1]

- ↑ Ricardo Sanchez Los Solidarios y Nosotros Toulouse 1966 p. 114

- ↑ Hans Magnus Enzensberger: The short summer of anarchy (1977), p. 75

- ↑ Federica Montsey, quoted from Hans Magnus Enzensberger: Der Kurz Sommer der Anarchie (1977), p. 245

- ↑ Hanns-Erich Kaminski in his diary about the Spanish revolution

- ↑ Hans Magnus Enzensberger : The short summer of anarchy (1977), p. 268

- ↑ Hans Magnus Enzensberger: The short summer of anarchy (1977), p. 271

- ↑ Hans Magnus Enzensberger: The short summer of anarchy (1977), p. 276

- ↑ Documentary film "On fighting and dying of the international brigades" (France 2015), broadcast on "arte", 2016-10-25, from 43:15 minutes.

- ↑ Carl Einstein: The column Durruti. The social revolution. Frontzeitung (edited by the German anarcho-syndicalists and the National Committee Spain of the CNT-FAI), January 3, 1937, accessed on October 17, 2017 .

- ↑ quoted from: Print among others: Abel Paz and the Spanish Revolution . Frankfurt / Main 2004, p. 8

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Durruti, Buenaventura |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Durruti Dumange, Buenaventura (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish syndicalist and anarchist revolutionary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 14, 1896 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Leon |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 20, 1936 |

| Place of death | Madrid |