Kronstadt sailors' uprising

The Kronstadt sailors' uprising ( Russian Кронштадтское восстание ), also known as the Kronstadt Commune, in the Soviet Union also often referred to as the Kronstadt anti-Soviet mutiny ( Russian Кронштадтский антисоветский from the end of March 21st until the 19th of the Baltic naval uprising from February 19 to 19 March sailors) the Soviet Navy , the Kronstadt fortress garrison and the residents of Kronstadt against the government of Soviet Russia and the politics of red terror and war communism .

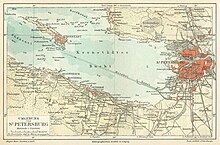

Under the motto "All power to the councils (Soviets) - No power of the party", the insurgents demanded that the dictatorial influence of the Communist Party of Russia (KPR) on political decision-making processes be withdrawn and that Soviet Russia be democratized. After the revolt had failed to spread to the mainland and other parts of Soviet Russia, the rebels used the fortifications of the Baltic Fleet from Kronstadt on the Kotlin Island, which were supposed to protect Saint Petersburg against attacks from the west. The Red Army troops used to crush the uprising were initially repulsed. However, the rebellious sailors could not withstand a second attack and surrendered.

After the surrender, many insurgents and uninvolved residents of Kronstadt were executed or imprisoned in the newly established “northern camps for special use” (SLON), provided they could not escape persecution by fleeing to Finland.

The uprising forced the transition from war communism to the new economic policy in Soviet Russia and, from 1922, in the Soviet Union.

prehistory

At the end of the Russian Civil War , Russia's economic situation was catastrophic. Large parts of the population suffered from hunger and epidemics were rampant. After the defeat of the enemy White Armies, the Bolsheviks, due to their autocratic and repressive rule, increasingly lost the support of Russian sections of the population who had previously supported Soviet rule. This was mainly due to the fact that the strict control of all economic activities (→ war communism ) was retained as before. The brutal repression of the rural population during the Tambow Peasant Uprising and many other uprisings contributed to exacerbating the hostile mood. The lifestyle of the communist rulers also gave cause for a revolt. The former leader of the Kronstadt Bolsheviks Fyodor Raskolnikow returned to Kronstadt in 1920 as the new commander of the Baltic Fleet, where he and his wife Larissa Reissner lived a very luxurious lifestyle.

The Kronstadt sailors were the main military power of the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution in Petrograd and, as an elite force, had supported the Communist Party in the civil war against the White Army and its western allies ( reconquest of Kazan on September 10, 1918 , defense of Petrograd in autumn 1919 ). When the news of the Red Army's actions against the Tambov peasants reached Petrograd, there were mass withdrawals from the Communist Party. In Kronstadt, which was considered the stronghold of the revolution, 5,000 sailors from the Baltic fleet left the party in January 1921.

Beginning of the uprising

On January 22, 1921, the Bolsheviks cut the bread ration prescribed in Soviet Russia by a third by decree. This decree sparked discontent and serious protests in the major cities of the RSFSR in the weeks that followed . On February 23, 1921, around 10,000 members of the Social Revolutionary and Menshevik parties began a strike in Moscow, which was joined by workers from the local steelworks. On February 24, 1921, strikes began in Petrograd in the Patronny ammunition workshops, the Trubotschny and Baltiski works and the Laferme factory. On the same day, the Petrograd Defense Committee of the KPR (B) ordered cursors to go to Vasilyevsky Island to disperse the workers gathered there. On February 25, workers from the Admiralty Workshops and Galernaya Docks joined the protest. A street demonstration by strikers was prevented by armed forces.

The Petrograd Defense Committee of the KPR (B), chaired by Grigory Zinoviev, called the unrest in the city's factories a rebellion and declared martial law on February 24. Trade unionists who organized the strikes were arrested. At the same time, the closure of the Trubotschny factory and the lockout of the strikers were ordered. The Bolsheviks began to gather Red Army troops in Petrograd. The sailors of the Baltic Fleet stationed in Kronstadt sympathized with the strikers. On February 26, a delegation of Kronstadt sailors visited Petrograd to investigate the situation in the city. After the delegation returned on February 28, the sailors of the battleships Petropavlovsk and Sevastopol held an emergency meeting, which resulted in a resolution being passed.

The Petropavlovsk resolution

The resolution passed on the battleship Petropavlovsk contained 15 demands. The most important of these were:

- Immediate holding of new elections with secret ballots, whereby the previous election campaign should have full freedom of agitation among the workers and peasants.

- Introduction of freedom of speech and press for workers and peasants, anarchists and left-wing socialist parties.

- Securing freedom of assembly for workers 'societies and farmers' organizations.

- Liberation of all political prisoners of the socialist parties and of all workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors imprisoned in connection with workers' and peasant movements.

- Immediate abolition of all Bolshevik armed groups from the confiscation of food and other products.

- To give farmers full freedom of action in relation to their land, as well as the right to keep livestock, provided that they can get by on their own means, that is, without using hired labor.

There are different views on the character of the protest movement that has emerged. In addition to the obvious opinion that the demands listed in the Petropavlovsk resolution emerged from the critical situation of the Soviet Russian population after the end of the civil war, historians also take the view that the protests could have been initiated by Russian emigrants from abroad. The historian Paul Avrich , who published a comprehensive book on the Kronstadt sailors' uprising in 1970, found evidence of this in the Bachmetev archive of Columbia University . This question has not yet been conclusively clarified.

The commander of the Baltic fleet Fyodor Raskolnikow was chased out of Kronstadt together with his wife Larissa Reissner . In the meantime news about the mood in the Baltic Fleet had reached Moscow. As early as February 28, the People's Commissar for Warfare Leon Trotsky asked by telegram for precise information about the background to the unrest.

Protests in Kronstadt and ultimatum from the Bolsheviks

On March 1, 1921, a meeting of the entire crew of the fortress, consisting of 16,000 members of the Navy and soldiers, took place at the anchorage in Kronstadt. The demonstrators carried banners with slogans such as “All power to the Soviets - No power of the party”, “The third revolution of the workers” or “Against the counterrevolution from the right and from the left”. The head of state of Soviet Russia Mikhail Kalinin attended the meeting on behalf of Lenin . He was the highest ranking agitator of the Bolsheviks. Kalinin gave a soothing speech in favor of the Communist Party, but was booed by the demonstrators. He was then allowed to leave the Kronstadt fortress unhindered.

During the meeting, a provisional revolutionary committee was formed, which included the leaders of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising. It originally consisted of five members:

- Stepan Petrichenko : seaman, chief clerk of the battleship Petropavlovsk and leader of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising

- W. Jakowenko: Kronstadt telegraph operator, Petritschenko's deputy

- Archipov: engineer, boatswain

- Tukin: Master in the Electromechanical Plant in Kronstadt

- Ivan Oreschin : Head of the third industrial school in Kronstadt

As events progressed, the committee grew to a total of 15 people.

During the demonstration it was decided to send 30 non-party delegates to Petrograd to publicize the demands of the Petropavlovsk resolution in Soviet Russia. The members of the delegation were arrested by the Bolsheviks on their arrival in Petrograd. The fleet commissioner N. N. Kuzmin and the chairman of the Kronstadt Soviet, P. D. Wassiljew, were arrested by the demonstrators on the night of March 1-2, along with 600 other members of the Communist Party. This completely eliminated the communist power apparatus in Kronstadt.

The following day, the protesters held a delegates conference with around 300 participants, at which essentially the demands of February 28 were reiterated. The Petrograd Defense Committee under Zinoviev had Petrograd declared a state of siege. This gave the committee authority over all law enforcement officers and all military units in the city. A curfew was imposed from 9:00 p.m. A ban on gathering people in public squares and streets followed. Then the committee began arresting numerous soldiers and sailors who were believed to be sympathizers of the Kronstadt protests. Military units considered unreliable were relocated to distant areas of Soviet Russia. Later, the families of Kronstadt sailors living in Petrograd were taken hostage by the Bolsheviks. With these measures, the Bolsheviks successfully prevented the protests from spreading to the mainland. The Petrograd workers were subsequently unable to support the insurgents isolated on the island of Kotlin. The strikes ebbed in early March after concessions from the political leadership under Zinoviev, who among other things organized the delivery of food to Petrograd.

On March 3, the Kronstadt Provisional Revolutionary Committee was expanded by ten members at Petritschenko's request. At the same time, the committee established a defense center that took over the military leadership of the insurgents. This headquarters included the former major general of the Imperial Russian Army Koslowski , the former rear admiral S. N. Dimitrew and B. A. Arkannikow, an officer in the Stavka until 1917 . Many members of the Communist Party in Kronstadt declared their resignation in protest against the despotism and bureaucratic corruption of the Bolsheviks.

At the same time, the Bolsheviks began to discredit the Kronstadt protests in various media as a reactionary, White Guard action. On March 4, an ultimatum was sent to the Kronstadt garrison by the Petrograd Defense Committee. The rebels should end their protests immediately or the Kronstadt fortress would be recaptured by military means. On the same day, the insurgents decided to defend Kronstadt against the Bolsheviks at a meeting of delegates attended by 202 people. The originally non-violent protests had escalated into armed struggle.

Crackdown

Before the riots began, the Kronstadt garrison consisted of a total of 26,000 soldiers and sailors. Not all garrison members took part in the revolt. Between 450 and 600 military personnel who refused to participate in the uprising were interned on the battleship Petropavlovsk. In addition, there were just over 400 deserters who had secretly left the fortress by the beginning of the fighting on March 7th. The Kronstadt garrison was the most heavily armed opposition group on Soviet territory up to this point and until the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. In addition to the well-equipped defenses of Kronstadt, the insurgents had two battleships, each with twelve 305 mm guns.

On March 5, 1921, Trotsky appeared in person in Petrograd. He gave the 7th Army under the command of Mikhail Tukhachevsky the order to draw up an attack plan for the storming of the Kronstadt fortress. The attack was to take place three days later on March 8th - the day the 10th KPR (B) party congress would open. The attackers were under additional time pressure that the early spring would thaw the ice on the Gulf of Finland, making a later storming much more difficult, if not impossible.

Trotsky threatened the rebels: They would be "shot down like hares" if they did not surrender immediately. Last attempts at mediation by an anarchist group, including Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman , failed.

On March 7, 1921, a total of 17,600 Red Army soldiers were ready to storm Kronstadt fortress. The forces were divided into a northern group consisting of 3,683 soldiers south of Sestrorezk and a southern group consisting of 9,583 soldiers near Oranienbaum and Peterhof under the command of Pawel Dybenko . About 4,000 soldiers were provided as reserves. At 6 p.m. on March 7, the Red Army began bombarding Kronstadt with artillery. In the early morning of March 8, the soldiers attacked the fortress. The preparation for the attack was inadequate: the soldiers did not have white camouflage suits and had to storm over the uncovered ice towards the fortress, which was additionally secured with barbed wire and minefields .

The attack was repulsed by the insurgents through fire from the fort's two battleships, artillery and machine guns, killing about 80 percent of the attackers. After this failure, the Red Army units deployed to suppress the uprising were demoralized. Two regiments of the 27th Infantry Division refused to participate in further combat operations and were disarmed. The soldiers believed to have instigated the disobedience were executed .

The Bolsheviks now realized that significantly more military strength would be required to break the insurrection. On March 10th, 300 delegates from the Xth Party Congress of the KPR (B) volunteered for the fighting in Kronstadt. A total of 50,000 soldiers were earmarked for the second attack. They were again divided into two groups, which were under the command of E. S. Kasansky with the political commissioner E. I. Weger (northern group) and A. I. Sedjakin with the political commissioner Kliment Voroshilov (southern group). The staging rooms were the same as during the first attack on March 8th. In contrast to the first attack, all soldiers received white camouflage suits. Boards and other aids were provided to safely negotiate fragile areas of the ice. During the whole time up to the start of the attack in the night hours of March 16-17, Kronstadt was continuously bombarded with artillery. In the meantime, the Kronstadt rebels were increasingly confronted with a shortage of ammunition and food, caused by the isolation of the fortress.

After the attack began, the Bolshevik soldiers were initially able to capture the unoccupied Fort No. 7 without a fight. Fort no. 6, however, offered bitter resistance and was only taken after long fighting. The later Soviet chief marshal of the armored forces Pavel Rotmistrow was one of the first Bolshevik soldiers to penetrate the fort. Fort No. 5 was only weakly defended, Fort No. 4 was also only captured by Red Army soldiers after hours of fighting. Parts of the Kronstadt fortress on the island of Kotlin were bitterly defended by the rebels. The crews of the batteries "Riff" and "Schanze" to the west together with many leaders of the rebellion crossed the ice to Finland after large parts of Kronstadt had been captured by the Red Army. The battleship Petropavlovsk was attacked by 25 Red Army aircraft around noon on March 17th. After 18 hours the battle was essentially over and Kronstadt was again in the hands of the Bolsheviks. Many Kronstadt rebels were shot on the spot by Red Army soldiers , and others were captured. About 8,000 rebels from Kronstadt escaped across the ice to Finland , where they were interned . According to the St. Petersburg Military Medical Service, 527 deaths, 4,127 wounded and 158 severe bruises were recorded between March 3 and 21. Later sources speak of more than 10,000 fallen in the Red Army (these numbers are not proven), including 15 delegates of the 10th party congress. There is no reliable information about the losses on the Kronstadt side.

Effects of the uprising

With the suppression of the uprising, the revolutionary phase that had shaken Russia since the spring of 1917 ended. From that point on, the dictatorship of the KPR (B) was consolidated for the long term.

Two decisions were of great importance for the history of Russia, which were decided in the spring of 1921 at the Xth Party Congress of the KPR (B) under the influence of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising. On the one hand, there was a strict ban on any factions within the Bolshevik Party, with which the leadership level around Lenin secured its power against internal party opponents. In addition, the demands of the Kronstadt sailors for a liberalization of the economy for a limited period of time were met. From 1921 to 1927, the New Economic Policy was decisive for the economic development in Soviet Russia and from 1922 in the Soviet Union. This enabled the country to recover from the horrors and devastation of the revolutionary years and the civil war under the rule of the KPR (B) and later the CPSU.

After the fighting in Kronstadt ended, several hundred rebels were shot immediately without trial. Another 2,000 insurgents were sentenced to death in later trials. Most of the remaining members of the Kronstadt garrison were sentenced to five years of forced labor and interned in concentration camps, the most important of which was the camp on the Solovetsky Islands . Others came to camps at the mouth of the Dvina in the White Sea , where it was customary to throw prisoners tied up into the freezing water to drown them. Only a few Kronstadt sailors were acquitted by the tribunals of the Petrograd Bolsheviks. 2500 civilians from the city of Kronstadt were exiled to Siberia, and very few returned. In 1922 the sailors who had fled to Finland were lured back to Russia under false promises and were also sent to the camps. According to the German historian Gerd Koenen , the criminal court against the insurgent Kronstadters exceeded the brutality with which the Paris Communards were massacred in 1871. The Bolsheviks deliberately staged a "beacon of terror" to mark a clearly visible "end to the civil war".

For many of the Red Army soldiers who were involved in the reconquest of Kronstadt, the participation meant a significant advantage for their later careers, as can be seen in the following examples:

- After the rebellion, Pawel Dybenko was the commander of various large units of the Red Army and from 1928 to 1938 the commander of various military districts in the Soviet Union.

- Mikhail Tukhachevsky was tasked with suppressing the Tambov peasant uprising just a month after the end of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising , and was later appointed one of the first five marshals of the Soviet Union .

- After the crackdown, Kliment Voroshilov was elected a member of the Central Committee of the CPSU and, after the death of Mikhail Frunze in 1925, took over the duties of Defense Minister of the Soviet Union in variously named posts.

- Pavel Rotmistrow was promoted to officer shortly after the uprising was put down. He later became chief marshal of the armored forces.

- Shortly after the crackdown, Jan Bersin became deputy head of the Soviet military intelligence service GRU and was head of the GRU from 1924 to 1935.

reception

Soviet representation

The author of the first official Soviet exposition of the events in Kronstadt was Leon Trotsky. He defined the term Kronstadt mutiny and linked it directly with a foreign conspiracy and the counterrevolutionary underground in Soviet Russia. This version was announced by Lenin during the 10th KPR (B) Congress in Moscow. In the 1930s, the assertion of disruptive work by Trotskyists and Zinovievists was added, who should have carried most of the blame for the destabilization of the situation. This version was reproduced dogmatically until the end of the Soviet Union.

During the entire period of the existence of the Soviet Union, the Kronstadt sailors were considered criminals and the uprising they initiated, according to the historian Ju, who is still considered authoritative in the Russian Federation today . A. Polyakov as dangerous . In Soviet historiography, the Kronstadt sailors' uprising was always viewed separately from the other revolutionary events of the Russian revolution. The Soviet texts look at events from the perspective of the CPSU and, like all other printed works published in the Soviet Union up to 1987 , have been edited by the Glawlit censorship authority . (→ censorship in the Soviet Union )

Trotsky himself never saw the suppression of the Kronstadt sailors' revolt as a mistake. He made the following comments to journalists in exile in Mexico in October 1938:

“I don't know […] whether there were innocent victims [in Kronstadt] […]. I am ready to admit that civil war is not a school for human behavior. Idealists and pacifists have always accused the revolution of excesses. The difficulty of the matter is that the excesses arise from the very nature of the revolution, which is itself an excess of history. May those who feel like it (in their poor journalistic articles) reject the revolution for this reason. I do not reject them. "

Anarchist representation and the 1968 movement

The anarchist Alexander Berkman , who stayed in Petrograd in February and March 1921 and who emigrated from Soviet Russia out of bitterness over the suppression of the protests, published a report in Berlin in 1923 on the Kronstadt sailors' uprising. In 1938 Ida Mett , who was in Moscow in 1921 , summarized the events of the Kronstadt uprising in a study form. She coined the term Kronstadt Commune . Until his death in 1945, Volin wrote a three-volume work on the Russian Revolution , the second volume of which , published in 1947, contained a detailed account of the Kronstadt uprising from an anarchist point of view.

In the course of the political movements around 1968 there was again an increased interest in alternative political models beyond party communism. This also included an increased preoccupation with Council-Republican models or Russian anarchist traditions of thought, as represented by Kropotkin or Bakunin. In this context, the works mentioned above were also received more strongly. For example, on May 11, 1971 at the Technical University of Berlin on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the crackdown, the Kronstadt Congress took place, at which, among others, Johannes Agnoli and Cajo Brendel gave speeches.

Representation by Western historians

As early as 1921, all issues of the Kronstadt Izvestia , the insurgents' newspaper, were published in Prague. This book was regarded as the main source by the American historian Paul Avrich , who in 1970 became the first Western historian to publish a monograph on the Kronstadt Sailor Uprising, as these documents, unlike the anarchist works, contain no subsequent retouching. In fact, these documents received little attention in the years that followed, up to the end of World War II, as the western world had little interest in the horror reports from Russia.

The western view of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising was only promoted after the beginning of the Cold War and was very much influenced by this ideological confrontation. The confrontation on the island of Kotlin was viewed by American historians in the 1960s as a general conflict between the Bolsheviks and the revolutionary masses. Many Western historians accepted the thesis spread by the anarchist authors about the selflessness of the Kronstadters, who were ideological fighters for democracy . The fundamental difference in Western historiography is the study of the causes of the conflict related to the entire Russian Revolution. The shortcoming of the Western presentation lies in the focus on the point of view of the rebels and their transfiguration as democrats in the western sense.

Reception after the end of the Soviet Union

On January 10, 1994, the President of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin issued a decree rehabilitating the Kronstadt insurgents and calling for a monument to be built in honor of all victims of the uprising. In the 1990s, with the disappearance of the Soviet censorship apparatus, a large amount of previously closed source material on various events in Soviet history was published. This enables a more objective presentation of the Kronstadt uprising.

literature

When using Soviet sources that were published up to 1987, the activities of the Soviet censorship authorities ( Glawlit , military censorship) must be taken into account in the revision of various contents in accordance with Soviet ideology. (→ censorship in the Soviet Union )

- Paul Avrich : Kronstadt 1921. University Press, Princeton 1970, ISBN 0-691-00868-X .

- Alexander Berkman : The Kronstadt Rebellion. Publishing house “der Syndikalist”, Berlin 1923, ( us.archive.org ; PDF; 2.4 MB).

- I. German : Trotsky. The armed prophet. Volume 3. Kohlhammer-Verlag, Stuttgart 1972.

- P. Dybenko : From inside the tsarist fleet for the Great October. Memories of the revolution. 07/11/1917 - 1927 ( Russian Из недр царского флота к Великому Октябрю Из воспоминаний о революции .. 1917-7.XI-1927 ), Woenny Vestnik (Miltärmagazin, Russian Военный вестник ), Moscow 1928 ( militera.lib.ru ).

- Orlando Figes : A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891-1924. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-8270-0243-5 .

- HE Gerbanowski: The storm on the forts of the mutineers. Military History Journal 1980, Issue 3. ( Russian С. Е. Гербановский: Штурм мятежных фортов. «Военно-исторический журнал», № 3, 1980 ), ISSN . 0321-0626 . (Soviet representation of the events)

- WA Goncharov, AI Kokurin (Ed.): Guardsmen of October. The role of the Balts in the establishment and strengthening of the Bolshevik regime. ( Russian Гвардейцы Октября. Роль коренных народов стран Балтии в установлении и укрепленики большевист ). Indrik, Moscow 2009, ISBN 978-5-91674-014-1 .

- Manfred Hildermeier : History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991. The rise and fall of the first socialist state. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43588-2 .

- AN Jakowlew (ed.): Kronstadt 1921. Documents on the events in Kronstadt in the spring of 1921. ( Russian А.Н. Яковлев (ред.): Кронштадт 1921. Документы о сокументы о сокументы о сокубытиях о сокубытиях в сойбытиях в Кненш21 , 1997, MF. ISBN 5-89511-002-9 .

- Gerd Koenen : The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-71426-9 .

- Frits Kool et al. (Ed.): Workers' democracy or party dictatorship. Volume 2: Kronstadt. Dtv, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-423-04115-3 . (therein: all the numbers of the communications of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee of Sailors, Red Army Soldiers and Workers of the City of Kronstadt )

- II Kudrjawzew (ed.): Kronstadt tragedy 1921: documents (in two volumes). ( Russian И. И. Кудрявцев (ред). Кронштадтская трагедия 1921 года. Документы (в 2-х тт) ) ROSSPEN, Moscow 1999, ISBN 5-8243-0049-6 .

- PC Roberts : "War Communism": A Re-Examination , Slavic Review 1970, Vol. 29, pp. 238-261, JSTOR .

- SN Semanov: The liquidation of the anti-Soviet Kronstadt revolt of 1921. ( Russian С. Н. Семанов: Ликвидация антисоветского Кронштадтского мятежа 1921 год ) Moscow.

- BW Sokolow : Mikhail Tukhachevsky: Life and death of the "Red Marshal". ( Russian Б. В. Соколов: Михаил Тухачевский: жизнь и смерть «Красного маршала». ) Rusitsch, Smolensk 1999, ISBN 5-88590-956-3 ( militera.ru ).

- Horst Stowasser : The uprising of the Kronstadt sailors. An-Archia, Wetzlar 1973.

- Volin : The Unknown Revolution. Die Buchmacherei, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-00-043057-2 .

- Volin: The Kronstadt uprising. Unrast-Verlag, Münster 1999, ISBN 3-89771-900-2 .

- Kliment Voroshilov : From the history of the suppression of the Kronstadt mutiny. ( Russian К. Е. Ворошилов. Из истории подавления кронштадтского мятежа. ), Military History Journal, Issue 3, 1961, pp. 15–35. (Soviet representation of the events)

- Military Encyclopedic Dictionary. ( Russian Военный энциклопедический словарь ) Military Publishing House of the USSR Moscow 1986. (Soviet account of the events)

- Johannes Agnoli, Cajo Brendel : The revolutionary actions of the Russian workers and peasants. The Kronstadt commune. Karin Kramer Verlag, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-87956-009-9 .

- Ida Mett: La Commune de Cronstadt: Crepuscule sanglant des Soviets. Cahiers Spartacus, Paris 1949, translated from the French by Jörg Putz.

Movies

- Civil War in Russia , Part 5: The Revolution Betrayed , ZDF 1968

- The sailors of Kronstadt. Documentary by Theodor Schübel, ZDF 1983.

- Ian Lilley: The Russian Revolution in Color - Part 2: The Road to Terror. English documentary, Channel 5 / Discovery Channel 2004.

Opera

On May 17, 1930, the State Academic Theater for Opera and Ballet in Leningrad premiered Vladimir Deschewov's opera Ice and Steel , which addressed the course and suppression of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising.

Web links

- Helmut Bock : The original sin of the Bolshevik revolution. Neues Deutschland , March 5, 2011, accessed on November 3, 2013

- Leon Trotsky: The scream about Kronstadt. January 15, 1938, accessed November 7, 2013

Individual evidence

- ^ Military Encyclopedic Dictionary. P. 376.

- ↑ Kokurin Goncharov: Guardsmen of October. Pp. 97-112.

- ↑ a b c d Figes: The tragedy of a people. P. 810.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. P. 7ff.

- ↑ Baberowski: Scorched Earth. P. 87.

- ↑ Baberowski: Scorched Earth. P. 81ff.

- ^ Seth Singleton: The Tambov Revolt (1920-1921). Slavic Review XXV, September 1966, p. 499.

- ↑ Figes: The tragedy of a people. P. 803.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. S. 60 ff.

- ^ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. p. 35.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. p. 39.

- ↑ Koenen: Die Farbe Rot , p. 816

- ↑ Hildermeier: History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991. P. 155.

- ^ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. pp. 235, 240.

- ↑ a b Jakowlew: Kronstadt 1921.

- ↑ Kokurin Goncharov: Guardsmen of October. P. 97.

- ↑ a b c d Voroshilov: From the history of the suppression of the Kronstadt mutiny. Pp. 15-35.

- ↑ Figes: The tragedy of a people. P. 809.

- ↑ Kudrjawzew: Kronstadt tragedy. P. 14.

- ↑ a b Figes: The tragedy of a people. P. 805.

- ↑ Gerbanowski: The storm on the forts of the mutineers. Pp. 46-51.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. p. 215.

- ↑ Goncharov, Kokurin: Guardsmen of October. P. 99ff.

- ↑ a b c Koenen: Die Farbe Rot. , P. 817.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. p. 216.

- ↑ Polyakov: The transition to NEP and Soviet agriculture , p. 30

- ↑ German: Trotsky. The armed prophet.

- ↑ Avrich: Kronstadt 1921. p. 255

- ^ Paul Craig Roberts: War Communism: A Re-Examination , p. 244