Class struggle

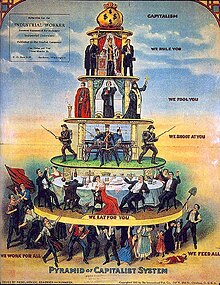

The term class struggle describes economic , political and ideological struggles between social classes . The term became popular thanks to Marxist theory. Accordingly, the driving forces of previous human history and especially of the revolutions are class struggles between exploiting and exploited classes, whose interests are interpreted as antagonistic . In the struggle of the social classes, according to Karl Marx, the contradiction between the social productive forces (the level of development of labor, the means of production and production techniques) and the relations of production (or the relations of ownership of the means of production) manifests itself as a class contradiction . Ultimately, by overthrowing the existing class rule, it brings about a revolutionary upheaval in the relations of production. In capitalism , the working class and the capitalist class face each other as central classes. The revolution of the working class, which Marx expected due to the crisis-ridden laws of development of the capitalist mode of production, would end class rule by abolishing all class differences.

Class struggle according to Marx and Engels

With the sentence “The history of all previous society is the history of class struggles”, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels opened - after the brief introduction - the first chapter of the Communist Party's manifesto . According to them, the previous history of mankind is a sequence of struggles of different classes against each other for rule, more precisely: for control of the means of production in the respective society.

Only in the (more deduced than empirically proven) original communities (“ primitive communism ”) with “tribal property”, joint production and appropriation there was still a classless society . This is based on the fact that no significant additional product has been generated through work . All members of society had to take part in the production of the essentials of life, so that no class could form that could have appropriated the extra work of others. All of them were involved in an immediate struggle for survival with nature. Large hierarchy differences were therefore largely unknown in early society.

The emergence of the class struggle is seen as a consequence of the emerging class society . As society succeeded in further developing the productive forces and creating a surplus product that exceeded immediate consumption ( subsistence ), this could be appropriated by a minority and used for purposes other than the immediate satisfaction of needs. From this a special position of power developed, which became more and more independent. This is how the ruling class emerged vis-à-vis the direct workers. All modes of production that followed "primitive communism" were modes of production of class societies. For the occidental area, Marx and Engels have developed a periodization of ancient , feudal and capitalist modes of production in the German Ideology . Later Marx (in the Grundrisse ) supplemented them with the Asian mode of production .

According to Marx and Engels, the ruling class initially assumes a productive function in the development of the productive forces, but in the further course it becomes its fetter, so that the historical necessity of the ruling class is called into question. The lower classes perceive the ruling class more and more to be superfluous, while it tries to defend its prerogatives. According to historical materialism , the likelihood of revolution increases when the development of the productive forces is hindered by the production relations determined by the respective ruling class . The further development of the productive forces is the motor that leads to the upheaval of the relations of production and thus to the overthrow of the ruling class. A new class seizes power and establishes new relations of production. According to this understanding, the history of mankind is a history of successive class societies, the sequence of which is by no means fully consciously brought about by the actors. Thus the bourgeoisie created bourgeois society after it had already developed as an independent trade, artisan and advocate class in the bosom of feudalism and absolutism , by eliminating the privileges of the nobility and clergy. The ultimate class society is their capitalism , in the course of which the productive forces are developed to such an extent that the material prerequisites of a classless society arise, which, however, must be consciously implemented in a revolutionary way.

Concept history

Before Marx

Nicolò Machiavelli already took the view in his Discorsi that the potential for conflict between the nobility and the bourgeoisie would keep political activity alive. Engels calls the fact that Henri de Saint-Simon, in letters from a resident of Geneva (1802, Lettres d'un habitant de Genève ), viewed the French Revolution as a class struggle between the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the dispossessed, "a highly ingenious discovery". Karl Marx described the French historian Augustin Thierry as the father of the class struggle in French historiography. The bourgeois French historians François Guizot , François-Auguste Mignet and Adolphe Thiers also saw the class struggle as a driving force of social development.

Marx

Marx only claims for himself that social classes are rooted in the relations of production of a particular social formation: “As far as I am concerned, I do not deserve the credit either for the existence of the classes in modern society or their struggle under them to have discovered yourself. Bourgeois historians had long before me presented the historical development of this class struggle, and bourgeois economists the economic anatomy of it. What I newly did was 1. to show that the existence of classes is merely tied to certain historical phases of production ; 2. that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat ; 3. That this dictatorship itself only forms the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society . "

20th century

After Marx, non-Marxists also used the term class struggle. Max Weber occasionally, but not always , puts this term in quotes and also writes of "class struggles" as well as "class revolutions" and "class action [...] against the immediate opponent of interests (workers against entrepreneurs)".

Ferdinand Tönnies stated the following in his book Geist der Neuzeit in 1935 :

“Hence the great and decisive, ever renewed struggle in society for 1. economic 2. political 3. spiritual moral power - which is always a ' class struggle ', which today manifests itself most directly and conspicuously as a dispute between capital and Labor, in which, however, many elements participate on one side or the other, who neither know and know each other as fighters of capital nor as such of labor, and are soon drawn into one camp - that of capital - or in the opinion that whose rule is self-evident, that is, just and equitable, put yourself in it, sometimes through your thinking, your ideas fall into it. "( Ferdinand Tönnies )

The French sociologist Michel Clouscard uses the term class struggle primarily in his book Les Métamorphoses de la lutte des classes (1996).

21st century

The redistribution of the tax burden from top to bottom in recent decades, combined with the rules governing transfer payments , also promoted the concentration of net income . An OECD study in 2011 found that the expansion of the low-wage sector in Germany has significantly reduced the wage share , which also contributed to the increase in the Gini coefficient in Germany. Hans-Ulrich Wehler describes this state-sponsored redistribution from bottom to top as a historically typical class struggle without collective actors with a well-developed class consciousness. On the other hand, there is a noticeable distance from conflict, because problems of power and rule are obviously not an object of the all-dominant neoliberal economics .

Even Wilhelm Heitmeyer sees a "class struggle from above" by This is "three core standards, which also hold together a society," a middle-class, which is based in assessing social groups by the standards of capitalist utility, usability and efficiency. ": Solidarity, Justice and fairness in dealing with one another ”. And that has "to do with the way elites express themselves, that is, people who have access to the media who are multipliers of certain things." Heitmeyer states "a kind of semantic class struggle from above against 'those below'".

The international lawyer Andreas Fischer-Lescano , who prepared an expert opinion on the activities of the “ Troika ” on behalf of the European Trade Union Confederation , said in an interview: “We are in the Europe-wide class struggle.” Specifically, he made this firmly on the erosion in the crisis countries collective bargaining , violations of human rights to health, social security and education as well as the impoverishment of large parts of the population through the austerity policy dictated by the Troika .

In the English-speaking world, the expression class struggle is disavowed as Marxist; Instead, the more objective or harmless-sounding class conflict is preferred, but recently also class warfare in the USA . Warren Buffett used this term in 2006 : "There is class war, right, but it's my class, the class of the rich, who wages war and we win." By contrast , class warfare is derogatory or belittling by conservative journalists and politicians Used for Obama's suggestion that the rich be more involved in reducing national debt, for example by Andrew Napolitano (Fox News Channel) or the leading Republican Paul Ryan . Paul Krugman contradicted this : "None of this is true. On the contrary, it are people like Mr. Ryan, who wants to exempt the very rich from carrying the burdens of the restructuring of our state finances, which lead the class struggle. ”Then Ryan also accused government-affiliated bureaucrats and“ speci-capitalists ”class struggle against everyone else.

George Soros said Ryan's point of view than that of hedge funds - Manager , which pained to have to pay more taxes. Finally, in 2011, Warren Buffett said, "The class war has been going on in the US for 20 years and my class has won."

In the New York Times on January 19, 2014, Krugman said there was “an aversion to the conclusions drawn from numbers that look almost like an invitation to class struggle - or, if you will, proof that the class struggle is already is in full swing, with the plutocrats on the offensive ”and it is“ a simple fact ”that the foundations of middle class society are currently being destroyed. "Almost never" are the defenders of inequality, who are "in the wages of the plutocracy", willing to talk about "the 1 percent or even about the real winners."

Class struggle in capitalism

Karl Marx described the class struggles in society of his time as follows: In capitalism the classes of the proletarians as owners of labor and the capitalists as owners of the means of production face each other in an antagonistic conflict of interests that leads to the class struggle.

According to Marx, the starting point for the class struggle in capitalism is the exploitation of wage labor by capital. The monopolized possession of the means of production by the capitalist class forces the propertyless proletarians under the “silent compulsion of economic conditions” to hire themselves out as wage laborers. They only receive a living wage that is necessary for their reproduction. The capitalists appropriate the increase in value generated by them in production and beyond that as unemployment income, as so-called surplus value . The economic interest of capital consists in constantly increasing the surplus value, that is, the difference between the hours worked by the employees and the hours paid. This gives rise to the constant “craving of capital for extra work ”: To increase the rate of surplus value , wages are reduced in relation to the return on work.

The simplest form is to extend the working day with the same wage ( absolute added value ). Since this comes up against - physical and legal - barriers, technical progress becomes the lever of the class struggle: making work more productive - and allowing it to be spent more intensively - serves to make labor cheaper ( relative surplus value ). Technical progress influences work and production conditions.

The class struggle is seen by the Marxists as the economic and political form of resistance of the proletariat. The other main antagonistic class (that of the capitalists) is also in the class struggle. It tries to restrict the conditions of the proletariat's struggle (e.g. by banning strikes). While the “class struggle from below” is openly propagated from the left and attacked from the right, class struggle from above has always been tacitly and naturally accepted. Not only Karl Marx knew this, but Adam Smith himself: "People from the same trade rarely come together for amusements or diversions without their conversation ending in a conspiracy against the public or a plan to increase prices." has not changed until today: “Since the balance of power of the classes is fundamentally structured asymmetrically in favor of capital, the power of capital appears to be 'normal' and its use as a class struggle ('from above') is regularly not or hardly noticed, while the Updating the ›power of work‹ also appears regularly and openly as class struggle (›from below‹). "In this way, the tax, educational and social policy of the state can also be used as instruments of the class struggle from above, such as in the USA, where taxes for the richest have been steadily reduced for decades.

In addition to the main classes, there are other classes, secondary classes, professions or strata (e.g. petty bourgeoisie, farmers, civil servants, academics) that can become allies of one of the two antagonistic main classes. The ideological and political influence on multipliers (intellectuals, teachers, journalists, politicians, etc.) and on institutions (media, schools, universities, etc.) can play a particularly important role in the formation of social consciousness under the conditions of a democracy . ) as well as organizations (e.g. political parties) play through one of the main classes or their interest groups (trade unions or employers' associations). This threatens the development of post-democracy , which in some places, e.g. B. in Greece, has already occurred, also in Germany, with - due to the balance of power - plutocratic character: "Today the international financial markets are probably the first world power, more powerful than even the USA." So focused on the action of a special interest group (" special interest group ”), the class struggle can be waged all the easier without the need for a conspiracy :“ You know each other, you help each other, that's enough. ”If“ the profound undesirable development in the western financial markets is not radically corrected, then it could our nations permanently cost prosperity and economic and political freedom and then that could be a contribution to the decline of the West. "

Class struggle as the mainspring of social development

See extensively in Historical Materialism .

The French sociologist Raymond Boudon accuses the Marxist sociologists of making excessive claims: They may have the best or most credible theory to explain social processes of transformation . However, he countered them with elementary examples of alternative explanations.

Quite simply, without Marxist terminology, but clearly and comprehensively Georg Büchner in 1835 in a letter to Karl Gutzkow : "The relationship between the poor and the rich is the only revolutionary element in the world."

Strike movements, uprisings and revolutions (chronology)

The following list contains a selection of overt social disputes between groups with opposing interests, some of which have already been interpreted in classical Marxist texts as exemplary class struggles, without this interpretation being shared by mainstream historical research. It does not claim to be complete or to only present generally recognized cases.

Antiquity

- 2650 BC BC to 2190 BC Uprisings in Egypt because of pyramids.

- 335 BC . Made BC Alexander the Great , the inhabitants of Thebes and 332 v. 30,000 inhabitants of Sidon became slaves.

- Class battles (Rome) from 494 BC Between plebeians and patricians , about Twelve Tables and Licinian-sextic legislation for the settlement of debts, until 287 BC. Chr. "Lex Hortensia" forms the conclusion on the political-institutional level.

- Several million slaves lived in the Roman Empire; since about 200 BC Several slave revolts were suppressed. So were from

- 136 BC BC to 132 BC 20,000 slaves executed by the Romans in the First Slave War

- 104 BC BC to 102 BC Second slave war

- Third slave war (revolt of Spartacus 73–71 BC) with 60,000 fallen and 6,000 executed slaves

middle Ages

- 1358 Jacquerie - peasant uprising in France

- 1370 Cologne weavers uprising

- 1378 Ciompi uprising in Florence

Early modern age

-

Early bourgeois revolution

- Reformation and the German Peasants' War from 1524

- Dutch uprising

- English Civil War

- 1744 Weavers' revolt ( révolte des Canuts ) in Lyon

- 1775 Mehlkrieg ( guerre des farines )

- 1785/6, 1793 and 1798 weaver revolts in Silesia

Modern

- French Revolution from 1789

- The silk weavers uprising in Lyon in 1831 - is often seen as the beginning of the modern labor movement

- Chartist movement in England 1838–1848

- 1844 Weavers' revolt in Silesia

- 1848 March Revolution in Germany and further revolutions in Europe

- 1871 Paris Commune

- 1905 Failed revolution in Russia

- 1917 February Revolution in Russia

- 1917 October Revolution in Russia

- 1918/19 November revolution in Germany / Spartacus uprising / council movement

- 1919/20 Factory occupations and workers' councils in Italy

- 1919 uprising in the French Black Sea Fleet

- 1920 Kapp Putsch and Ruhr uprising

Class struggle as a category of the analysis of the present

Michel Clouscard

In his study of the anthropology of capitalism, the French sociologist Michel Clouscard showed how the class struggle is changing through the integration of the new middle class, in which a new middle class - not proletarians, not bourgeoisie - with an indefinite function, the dialectic of the frivolous and the serious, is emerging was subjected. This replaces the frontal clash between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. From this a “capitalist civilization ” arises because it is the “first hedonistic society in history”, but which maintains the most obvious divisions of society . In a continuation of his criticism of Husserl and Sartre , Michel Clouscard describes the ideas of the Freudo-Marxists (Marcuse, Deleuze etc.) as a “ libertarian liberalism” that conceals the exploitation of workers through the consumption of the “frivolous”: “May 68, the perfect liberal counter-revolution of modernity that obscures the 'new reactionary'. "

Klaus Dörre

Klaus Dörre used to identify the neoliberal , the economic expansion serving Kommodifizierungs - and privatization policy, the term land grab . He assumes that land grabbing means “expansion of the capitalist mode of production inwards and outwards” and refers to Rosa Luxemburg's thesis that in “internal traffic” only limited parts of the value of the total social product can be realized. This forces expanding companies to realize some of the added value “abroad”. Dörre emphasizes that land grabbing "is always a political process based on state intervention". Transformation crises were “ideally suited to contain market socialization by withdrawing political investment fields from exploitation and transforming them into public goods through state intervention. In this way, an 'outside' arises for the molecular single-capitalist operations. Financial crises belong “to the modus operandi of new land grabbing” and “secondary exploitation ” means a “reserve army mechanism”. Secondary exploitation can “always be used when symbolic forms and state-political coercion are used in order to preserve an inside-outside difference with the aim of depressing the labor of certain social groups below their value, or these groups out of their own to exclude capitalist exploitation. ”Women, migrants and, above all, migrants are particularly suitable for this form of over-exploitation. Ceren Turkmen agrees. Dörre also states that returns and profits no longer appear as the result of economic performance, but as their prerequisite and that the market risk is borne primarily by the employees. The aim of the projects consists in the redistribution from bottom to top, [...] their leverage, return and profit targets in magnitudes that are not real economically realizable, then solve a structural compulsion to redistribute income and assets in this " casino capitalism" " out. State policy flanks this capital accumulation with measures that “amount to a circumcision, sometimes even to an 'expropriation' of the social property of large groups of dependent employees”. This leads to the "implementation of a flexible, market-centric mode of production, the functionality of which is essentially based on a revival of the reserve army mechanism," which, "combined with state pressure and social discipline , forces [...] into flexible forms of production."

Recently Dörre has noticed "that the old industrial class has been irrevocably transformed into a socio-ecological transformation conflict."

Hanns Wienold

Typical for capitalist companies is their legal independence as a "legal person" without moral responsibility. Ideologists and practitioners of neoliberalism call for the unconditional implementation of the “owner's will” in the maximization of shareholder value . “In these processes, blind capital and its aimless drive to increase gain the necessary concretization.” “As an entrepreneur the bourgeois is an individualist, as an agent or personification of capital he becomes a class man.” And the bourgeoisie is thus formed as a class in the “struggle for that Surplus product ". With the trading of stocks, government bonds and the new "derivatives" a separate investment sphere of capital emerged, an expanding financial market capitalism. The stock now seems to be capital in the hands of the stock owner. This “fictitious capital” becomes a speculative factor through and through. The bourgeoisie is also divided into factions: functioning owners ("middle class"), managers and rentiers; in addition, an elite of the bourgeoisie has emerged. Leslie Sklair sees a transnational bourgeoisie immediately given and as a unifying bond with the increase in the layer of managers of the transnational corporations: lifestyle and the glorification of consumption ( consumerism ), best practices and benchmarking as well as the examination of moral-ecological principles and demands.

Nicos Poulantzas

Class relationships are also important in terms of power and rule theory. But, like in sociology, the term became quiet in political science in the 1990s. For Nicos Poulantzas, there are innumerable hidden forms of disputes that ultimately always concern the added value achieved in the production process. Class interests cannot be determined a priori; rather, this determination is already part and result of struggles. How class struggles will be waged and in which direction they will push cannot be predicted. “The economic process is class struggle and thus includes power relations [...]. These power relations are specific in that they are linked to exploitation […]. ”The transnational capitalist class works“ in […] international organizations of the UN and transnational organizations such as the Bilderberg Group, Trilateral Commission and International Industrial Conference ”. Attempts to create transnational “private authorities”, as can be observed in the area of rating agencies, must also be of interest here. In this context, William I. Robinson speaks of the emerging transnational state apparatus and a transnational state. All important international and transnational organizations (UN, WTO, IMF, G 7/8, EU, OECD etc.) belong to this network-like state . Also, “the imperialist states not only look after the interests of their inner bourgeoisie, but also the interests of the ruling imperialist capital and those of other imperialist capitals, as they are connected within the internationalization process.” “Developments have changed the preconditions for class struggles. At the same time, the current crisis is expected to intensify the social disputes. In particular, it can be assumed that the 'class struggle from above', which has been vehemently waged in recent years, will be intensified, at least as indicated by the announcements about future austerity policies and tax breaks. "

literature

from Karl Marx :

- The German Ideology (together with Friedrich Engels ), 1847

- Communist Party Manifesto (together with Engels), 1848

- The class struggles in France 1848–50 , appeared in the first issue of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1850

- The eighteenth Brumaire by Louis Bonaparte , first published in The Revolution , New York 1852

- Outline of the Critique of Political Economy , 1858

- On the Critique of Political Economy , 1859

- The capital , 1867

- further reading

- Louis Adamic: Dynamite: History of the Class Struggle in the USA (1880-1930) . [Trans. from the American: Thomas Schmid and Joschka Fischer ]. Trikont, Munich 1974 (Classical representation of the militant class struggles in the USA).

- Jeremy Brecher: Strikes and workers revolts. American Labor Movement 1877–1970 . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1975.

- Colin Crouch , Alessandro Pizzorno (Eds.): The Resurgence of Class Conflict in Western Europe Since 1968. Volume 1: National Studies . Volume 2: Comparative Analyzes . Macmillan, London 1978.

- Rudolf Herrnstadt : The Discovery of Classes. The history of the term class from its beginnings to the eve of the July Revolution in Paris in 1830. Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1965.

- Benno Sarel: Workers Against “Communism”. On the history of proletarian resistance in the GDR (1945–1958) . Writings on the class struggle 43. Trikont-Verlag, Munich 1975.

- Klaus Tenfelde , Heinrich Volkmann (Ed.): Strike. On the history of the labor dispute in Germany during industrialization . Beck, Munich 1981.

- Reference book

- The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present , ed. By Immanuel Ness, Malden, MA [etc.]: Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 1-4051-8464-7 .

- Colin Barker, Werner Goldschmidt, Wolfram Adolphi : Class struggle . InkriTpedia. Preview of HKWM 7 / I 2008, columns 836–873.

Web links

- Entry ( memento of February 14, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) in Meyers Konversations-Lexikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marx-Engels-Werke , Volume 4. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 191959, p. 462.

- ↑ Marx-Engels-Werke, Volume 3. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1962, p. 22 ff.

- ↑ See the section “Forms that Precede Capitalist Production” in: Karl Marx: Grundrisse der Critique of Political Economy . EVA, Frankfurt am Main no year, p. 375 ff.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels: The development of socialism from utopia to science. In Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 8258 (see MEW, vol. 19, p. 195.)

- ↑ Augustin Thierry, Recueil des monuments inédits de l'histoire du Tiers état

- ^ Karl Marx: Letter to Friedrich Engels. July 27, 1854. In: Karl Marx: Friedrich Engels. Werke (MEW), Berlin 1953 ff., Volume 28, pp. 380–385. Quote p. 381.

- ^ Meyer's little lexicon. Leipzig 1968.

- ^ Letter to Joseph Weidemeyer, March 5, 1852 in: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Werke (MEW), Berlin 1953 ff., Volume 28, pp. 503–509, quotation pp. 507–508.

- ^ Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 680 ff.

- ^ Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 1012.

- ^ Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 682 regarding antiquity

- ^ Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 224.

- ^ Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 226.

- ↑ a b Ferdinand Tönnies: Complete edition. Volume 22. 1932-1936. Berlin 1998, p. 175.

-

↑ Regarding the ratio of income tax to VAT from 1991 to 2011 see:

Kai Daniel Schmid, Ulrike Stein: Explaining Rising Income - Inequality in Germany, 1991-2010 .

Frankfurter Rundschau: Economy Income - Poverty and Wealth - Inequality Income always unequal.

This and the cessation of the wealth tax enforcement since 1995 as well as the radical reduction in inheritance tax and the disproportionate tax rates for capital income (25%) and labor income (up to 45%): Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 79 f. - ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 71

- ↑ From 0.62 in 1993 to 2012. Jens Berger: Who owns Germany? The real rulers and the fairy tale of national wealth. Westend, Frankfurt / Main 2014, p. 27.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 33 f.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 71

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Munich 2013, p. 61 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Heitmeyer: Save yourself, who can on taz.de, Reichtum: Klassekampf von oben on zeit.de

- ^ New Germany: We are in the class struggle .

- ↑ Quoted by Jutta Ditfurth . Time of anger. Flyer from July 29, 2011.

- ↑ Original English: "There's class warfare, all right, but it's my class, the rich class, that's making war, and we're winning." - Ben Stein: Interview New York Times, November 26, 2006.

- ^ NY Times: Krugman the social contract .

- ↑ The "real sources of inequality in our country," he said (in a Savin the American Idea message to the Heritage Foundation on October 26, 2011), are "subsidies to corporations to enrich the powerful and empty promises to deceive the impotent. “The real class struggle that threatens us is instigated by a“ class of well-connected bureaucrats and speci-capitalists who try to rise above the rest of us, who are in charge, manipulate the rules of the game and their place at the top of society want to assert. " n. Chrystia Freeland: The super rich . Rise and rule of a new global elite. Westend, Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 219

- ↑ "Speaking as a person who would be most hurt by this, I think my fellow hedge fund managers call this class warfare because they don't like to pay more taxes."

- ^ Jeanne Sahadi: Soros: Why I Support the Buffett Rule . In: CNN , April 12, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ↑ Quotation from Marco d'Eramo , New Oligarchs - The rich in the US are getting richer? Oh - if only that was it!

- ^ NY Times: Krugman the undeserving rich .

- ↑ "The primary meaning of a positively privileged property class lies in the monopoly: ... when buying, ... when selling, ... the chance of wealth accumulation through unused surpluses, ... the chances of capital formation through savings (and) class (educational) privileges." Max Weber: Economy and society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 223 f.

- ↑ Social Policy Portal: Social Policy Chronicle .

- ↑ "Connection among the capitalists habitual and of effect which the workers forbidden and of bad consequences for them." Karl Marx, Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte from 1844 , [1. Manuscript] wages, [471]

- ^ Adam Smith: Wealth of Nations , Chicago 1976, Book I, p. 144; quoted n. John K. Galbraith: "Anatomie der Macht" Munich 1989, footnote 6 to p. 127 on p. 213.

- ↑ Berlin Institute for Critical Theory (InkriT) Class Struggle A: ṣirā ‛ṭabaqī. - E: class struggle. - Q: lutte des classes. - R: Классовая борьба (Klassovaja bor'ba). - S: lucha de clases. - C: jieji douzheng 阶级 斗爭 Colin Barker (I.), Werner Goldschmidt (II.), Wolfram Adolphi (III.) HKWM 7 / I, 2008, columns 836–873

- ↑ Social Policy Portal: Social Policy Chronicle .

- ↑ Warren Buffett: America is a class war

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : The new redistribution. Social inequality in Germany. Beck, Munich 2013. pp. 60 ff.

- ^ Alan B. Krueger : The Rise and Consequences of Inequality in the US. Washington DC 2011.

- ↑ Paul Krugman, quoted in n .: J. Bergman: The rich are getting richer - also in Germany , in: Leviathan 32. 2004, p. 185.

- Jump up pages: The Watchdogs of the Power Elite: Noam Chomsky's Critique of the Intellectuals .

- ↑ Max Weber: "The primary importance of a positively privileged working class lies in ... securing their employment opportunities by influencing the economic policy of political and other associations." Max Weber: Economy and Society. Outline of understanding sociology. Neu Isenburg 2005, p. 225.

- ↑ Freitag.de: All state authority comes from the people

- ↑ Bernd Schünemann on Deutschlandfunk on April 20, 2012: “For several years we have had the catchphrase post-democracy, the control of the political system through the financial market and thus the abolition of, the de facto abolition of democracy. That was already diagnosed back then and you can see how it actually repeats itself in increased form. And you can already see how, so to speak, the governments are being driven by the financial actors. And again and again we hit the slogan, which I almost don't like to hear anymore, “there is no alternative”, and that's how you whip it through. And apparently nobody in our ruling conglomerates in Germany and Europe understands that this touches the foundations of our parliamentary democracy, as we actually built them from the total collapse and decline in the 1950s. "

- ^ Roman Herzog : The economic putsch or: What is behind the financial crises on Germany radio.

- ↑ From the mouth of Chancellor Angela Merkel on September 2, 2011 on Deutschlandfunk: “We live in a democracy and that is a parliamentary democracy and that is why the budget law is a core right of parliament and in this respect we will find ways like parliamentary co-determination is designed so that it is still in line with the market. "

- ↑ Erich Streissler: Exchange rates and world financial markets , Wirtschaftspolitische Blätter 4/2004, p. 387

- ↑ Horst Köhler : Capitalism - creative destruction? .

- ^ Raymond Boudon: La logique du social. Introduction à l'analyse sociologique. Hachette Littérature 1979. p. 196.

- ^ Georg Büchner: Works and Letters. Neu Isenburg 2008, p. 590.

- ^ Hans Dollinger: Black Book of World History. Frechen 1999, p. 11

- ^ Hans Dollinger: Black Book of World History. Frechen 1999, p. 41

- ↑ "The class struggle of the ancient world z. B. moves mainly in the form of a struggle between creditor and debtor and ends in Rome with the downfall of the plebeian debtor, who is replaced by the slave. "Marx:" Das Kapital. "Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 3519 (see MEW Vol. 23, pp. 149–150)

- ↑ The "class struggles" of antiquity - insofar as they were really "class struggles" and not rather class struggles - were initially fights between peasant (and probably also: artisan) debtors threatened by debt bondage against creditors living in the city. Max Weber : “Economy and Society.” Neu Isenburg 2005. P. 682.

- ^ Ploetz, Freiburg i. Br. 2003

- ^ Hans Dollinger: Black Book of World History. Frechen 1999, p. 43 ff.

- ^ Hans Dollinger: Black Book of World History. Frechen 1999, p. 41

- ^ In Wilhelm Zimmermann: The great German peasant war. Berlin 1974, p. 5 is preceded by a quote from Friedrich Engels, The German Peasant War , which says: “If, on the other hand, Zimmermann's account ... fails to demonstrate the religious and political issues of that era as a reflection of the simultaneous class struggles; when she sees in these class struggles only the oppressor and the oppressed, the bad and the good, and the eventual victory of the bad; [...] ".

- ↑ “Even in the so-called religious wars of the sixteenth century, it was above all a matter of very positive material class interests, and these wars were class struggles, as well as the later internal collisions in England and France. If these class struggles wore religious shibboleths at that time, if the interests, needs and demands of the individual classes were hidden under a religious blanket, this does not change anything about the matter [...] "Engels, Der Deutschen Bauernkrieg. Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 9021 (see MEW Vol. 7, p. 343)

- ^ Walter Markov, Albert Soboul: 1789. The Great Revolution of the French. Berlin 1972, p. 27.

- ^ Walter Markov, Albert Soboul: 1789. The Great Revolution of the French. Berlin 1972, p. 72.

- ^ Robert Kurz : Black Book Capitalism. Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 26.

- ↑ Engels praised Saint-Simon's analysis : “ To understand the French Revolution as a class struggle, not just between the nobility and the bourgeoisie, but between the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the dispossessed, was a most ingenious discovery in 1802.” Engels: The Development of socialism from utopia to science. Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 8258 (see MEW Vol. 19, p. 195)

- ^ “In 1831 the first workers' uprising took place in Lyon; From 1838 to 1842 the first national labor movement, that of the English Chartists, reached its climax. The class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie came to the fore in the history of the most advanced countries in Europe, to the same extent that there developed on the one hand great industry and on the other hand the newly conquered political rule of the bourgeoisie. ”Engels: Herr Eugen Dühring's upheaval in science. Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 7674 (cf. MEW Vol. 20, pp. 24-25)

- ^ Robert Kurz: Black Book Capitalism. Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 27 f. - literary. Processing at Heine, Hauptmann et al

- ↑ Karl Marx: Class Struggles in France 1848 to 1850 MEW Vol. 7 (on this introduction by Friedrich Engels)

- ↑ Ders .: Revolution and Counterrevolution, Der Wiener Oktoberaufstand MEW Vol. 8, p. 63

- ↑ "All that is needed is a connection in order to centralize the many local struggles of the same character everywhere into a national, class struggle." Marx / Engels: Manifesto of the Communist Party. Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 2633 (cf. MEW Vol. 4, p. 471)

- ↑ “The June fight in Paris, the fall of Vienna, the tragic comedy of November Berlin, the desperate efforts of Poland, Italy and Hungary, Ireland's starvation - these were the main moments in which the European class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the working class came together, which we demonstrated that every revolutionary uprising, however remote the class struggle may seem, must fail until the revolutionary working class wins, that every social reform remains a utopia, until the proletarian revolution and the feudalist counter-revolution (sic!) join in a world war measure the weapons. […] Now, after our readers saw the class struggle develop in colossal political forms in 1848, it is time to dwell more closely on the economic conditions themselves on which the existence of the bourgeoisie and its class rule are based, like the slavery of the workers ". Marx: wage labor and capital. Marx / Engels: Selected Works , p. 2690 (cf. MEW Vol. 6, p. 397 f.)]

- ↑ “The highest heroic upsurge that the old society was still capable of is the national war, and this is now proving to be a pure government fraud, which has no other purpose than to postpone the class struggle and which flies aside as soon as the class struggle in the civil war flares up. “Marx: The Civil War in France. Marx / Engels: Selected Works, p. 12460 (see MEW Vol. 17, p. 361)

- ↑ cf. L'Être et le Code (Being and Codification), Préface (Introduction), L'Harmattan, Paris, 2003

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, pp. 113–151

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 120

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg: The accumulation of capital - An anti-criticism. In: Gesammelte Werke, Vol. 5, Berlin 1975, pp. 413-523.

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 124

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 142

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 126

- ↑ Ceren Türkmen: Rethinking Class-Making. On the historical dynamics of class composition, guest worker migration and politics. In: Hans-Günter Thien: Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, pp. 202-234.

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 130 f.

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 134

- ^ Strange: Casino Capitalism. Oxford 1986

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 134

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism: Münster 2010, p. 134

- ^ Klaus Dörre: Land grabbing and social classes. On the relevance of secondary exploitation. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 135

- ↑ Klaus Dörre on Friday 29/2020: [1]

- ^ Hanns Wienold : The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 239.

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 241.

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 243.

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 243.

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 248 ff.

- ↑ Leslie Sklair: The Transnational Capitalist Class. Oxford 2001

- ^ Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 276.

- ↑ Joachim Hirsch , Jens Wissel : Transnationalization of Class Relations. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 287.

- ↑ Nicos Poulantzas: The internationalization of capitalist conditions and the nation state. In: Hirsch / Jessop / Poulantzas: The future of the state. Hamburg 2001, pp. 19-70.

- ^ Nicos Poulantzas: State theory. Hamburg 2002, p. 65, cit. n. Ceren Türkmen: Rethinking Class-Making. On the historical dynamics of class composition, guest worker migration and politics. In: Hans-Günter Thien: Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 211.

- ↑ Leslie Sklair: Social movements for global capitalism: the transnational capitalist class in action. In: Review of International Political Economy. 4: 3 Autumn. 1997, p. 527

- ↑ Timothy J. Sinclair : Bond-Rating Agencies and Coordination of Global Political Economy. In: A. Clair Cutler: Privat Authority and International Affairs. New York 1999, pp. 153-167; quoted after: Hanns Wienold: The presence of the bourgeoisie. Outlines of a class in: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.), Klassen im Postfordismus Münster 2010, p. 277.

- ^ Wiiliam I. Robinson: A Theory of Global Capitalism. Production, Class and State in a Transnational World. Baltimore / London 2004, pp. 36, 85 ff., Cited above. n .: Joachim Hirsch, Jens Wissel: Transnationalization of class relations. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 291.

- ↑ Nicos Poulantzas: The internationalization of capitalist conditions and the nation state. In: Hirsch / Jessop / Poulantzas: The future of the state. Hamburg 2001, p. 56, cit. n. Joachim Hirsch, Jens Wissel: Transnationalization of class relations. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 302.

- ↑ Joachim Hirsch, Jens Wissel: Transnationalization of Class Relations. In: Hans-Günter Thien (Ed.): Classes in Postfordism. Münster 2010, p. 306.