Early bourgeois revolution

Early bourgeois revolution is a term from Marxist economic sociology and history . This is intended to describe revolutionary movements from the end of the Middle Ages (from around 1450), which are characterized by the following lines of conflict:

- the struggle of the peasant class against the feudal nobility class and

- the struggle of the bourgeois representatives of early capitalism against the representatives of feudalism .

By integrating the agrarian question into the revolutionary program, the interests of the peasant class were taken into account, and bourgeois and peasant groups in England, the Netherlands and Germany succeeded in taking joint action.

From the point of view of Marxism , these socio-political forces or currents had the goal of overcoming their economic and political fragmentation. This included demands from the farmers for:

- higher share of the return on production

- Loosening of the feudal order

- improved access to the commons .

Examples of early bourgeois revolutionary phenomena were the Hussite movement , the Reformation and the peasant war in Germany . The Dutch struggle for freedom with the revolution that began in 1566/67 was also shaped by the struggles of the bourgeois class against the nobility. The same happened in the Kingdom of England during the Glorious Revolution . While the bourgeois class on the north-western continental margin of Europe was finally able to assert itself against the aristocratic class in the 17th century, as a result of the late medieval agricultural crisis, the eastern and central continental areas were subjected to renewed refeudalization until the middle of the 19th century , as was the serfdom of the peasants lasted. This mainly affected the East Elbe areas, Poland ( aristocratic republic ) and other eastern European countries.

Preparatory popular movements at the turn of the Middle Ages to the modern age

In individual European countries, popular movements reached beyond local borders as early as the second half of the 14th and 15th centuries and grew into major peasant wars and urban uprisings:

- in France the Jacquerie (1358) and the Shepherd Movement (1382-1384)

- in England the Peasants' Revolt under the leadership of Wat Tyler (1381)

- in Italy the movement led by Fra Dolcino (1300-1304) and the Tuchini uprising in the Canavese in Piedmont (1382-1387),

- in Bohemia the Hussite Wars (1419–1434),

- in Spain the uprisings in Castile (1437), in the Balearic Islands (1450/51) and in Catalonia (1462–1472)

- the uprising under György Dózsa in Hungary

- Peasant riots in Spain in 1505

- Bundschuh movement of 1517

- Comuneros uprising from 1520 to 1522 in Spain

- Peasant Riots in England 1536 to 1539, 1549

Despite its defeat, the large-scale peasant movement of the Hussites had a considerable international response. The appearance of the English Lollards and, above all, the Hussite Wars supported the Reformation movement and the class struggle in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

These previous surveys lacked essential features that are essential for early bourgeois revolutions. The new social conditions brought about by capitalist development did not yet exist. Uniform domestic markets or supra-regional market relationships had not yet been established, so local borders could not be overcome. There was a lack of general opportunities for cross-group cooperation or agreements. The older and discontinued Marxist historiography in the 20th century always wrote of the so-called « class alliance ». All of these uprisings were a qualitative preliminary stage that ultimately only prepared the following revolutions, which did not enter history in a vacuum, but were based on corresponding previous regional uprising experiences and imitated their patterns.

Social upheavals from the late Middle Ages to the modern age

The ruling social order in the late Middle Ages was feudalism. Feudal dependencies and class structure exist, along with others, in territorial ties and the bondage of peasants to the landlords . The landlord was not the owner of the land, but received it as a fief from higher-ranking nobles. The system had its advantages as long as natural economy was predominant and the ruling system was generally weak. It promoted the territorialization of Europe, expressed by the boom in castle building . Economically and from a productive point of view, however, the system was extremely ineffective. Due to the unfree position of the vast majority of its members, it prevented economic activity. As a result, production rates were institutionally weak, the rate of progress just as low, and general mobility just as weak. This rigid, unfree and hierarchical-pyramid-like system began to erode in the late Middle Ages with a simultaneous increase in the differentiation of society. Strong social niche zones had formed in the urban centers of Europe and they continued to expand. City federations had established their own order in the late Middle Ages. Town and country formed a sharp legal dividing line. In addition, the medieval legal principle that city air makes you free was applied .

The plague, population decline and climatic changes led to permanent crises in Europe in the 14th century. Whole landscapes were depopulated, many farms were deserted. The crisis of the 14th century subsided over the course of the 15th century. The fall in prices in the agricultural sector and in land rents had led to a permanent economic crisis for the rural nobility. From this a permanent crisis of the feudal nobility developed. These representatives of this class therefore increasingly acted as robber barons , with the consequence of increasing legal uncertainty in Europe. The feudal aristocratic income sank, while in the late Middle Ages the property rights of the peasants had increased again and they were in a good starting position at the beginning of the early bourgeois revolutions. However, this rural economic crisis did not apply to the city. Their industry and trade flourished, and between 1450 and 1540, silver production in Central Europe increased fivefold. Cloth and wool production also experienced a strong upswing. Advances in the armaments sector , innovations in the metal industry , papermaking and also book printing opened up new employment opportunities. The expansion affected technical, organizational and economic changes. This included the first beginnings in the publishing system , which had already been tried out in Italy and was now also beginning to establish itself in Germany. The transport system and also the money in circulation increased.

Trading capital in particular enjoyed a strong upswing. In the Baltic Sea trade , the Hanseatic League held the monopoly for a long time and maintained long-distance trade relations. In the south, the Upper German cities benefited from their favorable location between the northern Italian and Dutch commercial and industrial centers. Numerous exhibition locations at the junctions of the flow of goods had been established ( Reichsmessen ). Cities specialized in active trade and established branches and factories in the most important European countries . At the same time powerful trading companies such as the Fugger and Welser came into being , which combined trade in goods with mining and banking and accumulated great fortunes. With the increase in cashless payment transactions , important new financial centers are emerging that are closely related to the world stock exchanges in Lyon and Antwerp . The commodity-money relationships had intensified and their monetary exchange logic began to expand to other social areas. This degree of expansion into feudal systems , for example , which were organized according to birthright and not according to capital-based exchange logics, was still at a very early and low stage of development.

The nobility recovered from the weakness they experienced during the late medieval crisis in the 14th and early 15th centuries. Until then, the aristocracy kept largely out of the inner-village affairs. This changed in the following time in the course of the attempts of the wealthy nobility to expand their own returns with the sharply increasing grain export. To this end, the landed gentry tried to carry out an expropriation campaign against the subjects together with the sovereign . The free peasant thus got into the second serfdom . This expropriation process was most successful east of the Elbe . A lordly process of intensification began in southern and central Germany, too , which, according to Peter Blickle, also bore traits of a second serfdom. The intensification of rule did not affect the level of taxes, which remained stable, but the legal position of the peasants. Their freedom of movement was increasingly restricted. The nobility also began to intervene in the internal affairs of the villages. They acquired numerous administrative and judicial powers from the community. The peasant resistance to the establishment of a manorial economy should be broken. No longer representatives elected by the community, but officials appointed by the rulers, mostly from families in the imperial city , exercised the police, administrative and judicial tasks. The officials arranged for the collection of the fines, checked the measurements, inspected the mills, carried out border inspections, supervised the tithe collection and checked the bills. In some cases they were subordinate to police troops that were set up to maintain internal security against the opposing peasants. The farmers had to bear the costs of expanding their rule themselves.

Ultimately, the period around 1500, which was described by Marxist historiography as a “crisis for society as a whole”, was above all a cultural and spiritual time of upheaval - with the open arrival of the Renaissance and humanism in Europe. In contrast, the economic and demographic crises of the late Middle Ages, with the tensions and burdens they triggered, had already been partially overcome. Politically, too, there had previously been much more turbulent crises and conflicts in Europe than was the case around 1500, for example the Wars of the Roses in England or the Hundred Years War in France.

Ultimately, the emerging early capitalism is said to have disintegrated feudal society. The bearers of the old feudal order, with the strongly secular and strongly materialistic church as the most important supporting feudal force, were internally at odds and could not escape these forces that were forming.

According to Günter Vogler , Germany and Europe came to the end of the 15th century in the epoch of transition from feudalism to capitalism , whereby the constitutive characteristics for the type of early bourgeois revolutions were achieved. Europe entered the epoch of bourgeois revolutions in which the bourgeoisie gradually fought for political power. The prerequisites for an early bourgeois revolution are:

- Accumulation of capital

- Formation of the world market

- Presence of centralized monarchies

- Existence of bourgeois cultures and ideologies.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the early modern bourgeoisie was primarily concerned with the question of property, which was the livelihood of the citizens. To this end, all feudal property rights should be abolished. Free competition was to be asserted in favor of the existing manors, guilds , monopolies, which fettered the developing proto- industrial (bourgeois) trade.

Starting conditions in the individual states of Europe

The unequal distribution of the goods produced led to political crises in England but also in France, Catalonia, Portugal, Naples and Palermo . The emerging revolutionary currents were triggered because the early modern state superstructure tried to strengthen its position. The most significant early bourgeois surges took place from 1517 to 1689, first in the Holy Roman Empire, then in what is now the Benelux countries, and then in England. The social upheavals of the 16th century, first in the Holy Roman Empire, later in the Netherlands and in the 17th century in England, were based on different starting conditions and stages of development of the individual societies. The early bourgeois revolutions in the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire came at a time when, unlike later in England and France, economic and state centralization in these states was only poorly developed. Yet there were also parallels. The states of these areas at that time were among the most progressive in the world and went through a reformatory movement, which led to strong progress in secularization there. In addition, these areas were more urbanized than other Reformation areas such as Scandinavia. The resulting higher and denser exchange and movement rate had a favorable effect on social reformatory leaps.

While in the German states around 1500 and also in the Ancien Régime around 1789 feudal production conditions dominated in the agricultural sector, the Netherlands and England presented themselves as further advanced in the run-up to their own revolutions, visible in the level of proto-accumulation of capital achieved in the Degree of development of leases , the emergence of a bourgeois nobility whose interests were closer to those of the urban bourgeoisie , so that a socio-political basis for compromises was given. Such a new nobility did not exist to any significant extent in the German states or in France. The confrontation between the peasantry and the feudal nobility was therefore more pronounced there.

Early bourgeois revolution in the German cultural area

The call of the Reformatio had become more and more urgent in the Holy Roman Empire, since multiple attempts by the emperor and the estates to reform the state had failed and the class contradictions both in the country and in the cities and in their areas of society had come to a head. The beginning early capitalist development intensified this. In view of the not yet fully developed class antagonisms between the bourgeoisie of this time and the feudal nobility, it is no contradiction to the bourgeois character of the Reformation that princes, nobles, and even high church representatives sympathized with it.

The first Reformation of Martin Luther was anti-Roman in its approach. The Protestant German princes developed an anti- unitarian approach for themselves , which was directed against the universalist empire under the leadership of the Habsburgs . As a result of the Reformation, the political balance of power shifted in favor of the secular princes and urban upper classes. Thus the Reformation from Above was not a social-revolutionary uprising of the plebeians and peasants.

The essence of the Reformation was also primarily purely theological and not revolutionary. It was aimed at internal church reform. However, the Reformation statements and theses also contained potentially system-breaking elements. After all, the Reformation movement had a revolutionary effect in that it questioned social foundations and the status quo. As a result, the Reformation spread to a society that was in crisis in 1517 and also sought reforms. The social program aspects of the Reformation reform program contained:

- Reforms in the interests of the socially weak, the underprivileged, the exploited and the oppressed

- Formulation of new egalitarian models of society based on the gospel

The decisive step for the cleavage of the reform movement in the bourgeois-Lutheran Reformation and of Thomas Munzer cited people Reformation had with Luther's Address to the Christian Nobility of the German nation held by the 1520th The social movement that resulted from the Reformation formed a symbiosis of Reformation theology and social movement. Otherwise, the radical Reformation presented a rather heterogeneous picture. Thomas Müntzer, for example, combined church reform with criticism of the existing political and social conditions, as was expressed in his prince sermon of 1524. The movement reached its climax in the German Peasants' War in 1525. The peasant uprising began in the Black Forest and on Lake Constance and extended to Swabian and Franconian areas, to Tyrol , Salzburg , Württemberg and Thuringia . In the spring of 1525, the Revolutionary Manifesto of the Twelve Articles was proclaimed in Memmingen . But the militarily inexperienced peasants had nothing to oppose the well-armed mercenary armies of the princes. After bloody battles, the peasants' war ended with a defeat for the peasants.

The German Peasants' War was ultimately the culmination of a long chain of agricultural revolts in the late Middle Ages , which resulted from the conflict between peasant partial autonomy and the right to rule by the state. According to Horst Buszello , two key concerns of the farmers stand out:

- the desire for personal freedom and equality (without intending to generally abolish the class system)

- Preservation and maintenance of inner-village autonomy, a demand that converged with the urban bourgeoisie .

On the whole, it was a limited political revolution aimed at changing the distribution of power within the existing system and not at creating entirely new structures. The German Peasants' War thus still belonged in the framework of late medieval constitutional development.

The revolution between 1517 and 1525 is understood as a type of early bourgeois revolution. However, proving your specifically bourgeois character continues to cause great difficulties. The complex as such has not yet been fully worked up. A minimal consensus is the finding that the Reformation was shaped by a strong urban connection, without the Reformation having a "bourgeois" effect. The concept of citizens in the early 16th century differed significantly from the concept of citizens in civil society, which emerged much later . This problem is well known in the history of science, but it is considered more legitimate from a historical point of view because it is a process that is conducive to knowledge on all sides and is accepted as an "open research process". For the 16th century, the term early capitalist bourgeoisie was established instead of the bourgeoisie . The German events of the 16th century are therefore interpreted from a Marxist perspective as a “bourgeois revolution without a bourgeoisie”. In Eastern historiography, the bourgeoisie would not only have failed as a revolutionary force in the sixteenth century, even betrayed the revolution. The intervention of "the masses " became necessary. Peasants, plebeians , and petty bourgeoisie became the real agents of the movement. The anti-feudal fighters had to be denied success, "because the class hegemon of a bourgeois revolution was lacking, because the bourgeoisie did not want to position themselves at the head of the movement against feudalism."

The bourgeois forces, especially in the center of the Reformation, Central Germany , were still largely limited to ore and silver mining in the Ore Mountains , which was very prosperous at that time. Merchants invested in Kuxe during the mining industry . Because of the monopoly ownership of the sovereigns, these bourgeois forces entered into arrangements with the feudal lords in order to be able to become economically active at all. The guilds with their protectionist and monopoly structures continued to exist in the cities . In agriculture, too, the late medieval agricultural crisis led to a tightening of property rights to the disadvantage of free farmers . The increasing importance of goods-money relationships, which was strengthened by the increasing amount of available silver as a means of payment , gradually dissolved the feudal forms of dependency, but it did not have a disruptive effect on social conditions. On the contrary, the tightening of the feudal direct domination and servitude relationships led to a stronger bond between producers and producers and the local feudal lords ( landowners ) and thus to their disenfranchisement. While the social relations of production could not break away from the feudal order (and thus not be subject to capital either), the development of commercial capital was excluded, which flourished and developed independently.

Since the capital forces developing around 1500, such as the Fuggers, were immature and divided, according to Adolf Laube they combined with the feudal forces and did not develop their own class consciousness in the German cultural area . The cities ruled by the wealthy and educated bourgeoisie did not act differently from the feudal lords and saw their own economic position threatened by the peasants. Patricians and guilds, the most influential elements of the bourgeoisie, had already done their business with emperors and kings, with princes and lords and were therefore already interested in stabilizing the old order and in no way interested in its execution. In this way they prevented the advancement of their own interests in the ongoing chain of arguments, which would have required the alliance with the revolutionary forces and not their elimination. According to this thesis, the "revolutionary popular masses" could not lead the revolution to success on their own initiative without the leadership of the bourgeoisie, which as a class represented the new relations of production.

From these specifically German conditions developed the Marxist theory of bourgeois development in Germany as a "single ongoing misery", which, however, ultimately brought victory over the feudal forces in the centuries-long struggle between progress and reaction , which was marked by many setbacks and painful detours have.

The defeat of the German Peasant War meant a severe setback for the bourgeoisie and the peasants. The tendencies of bourgeois society were thereby brought to a standstill for the time being. Many imperial cities were re-annexed to princely territories. The real beneficiaries were the princes and in the following years the nobility's dependence on the princes increased. This was followed by a princely reformation , which was more backward than the Henrician Reformation in England, and with the reintroduction of serfdom in East Elbia meant extensive refeudalization. However, the early bourgeois revolution as a Reformation in Germany did not suffer defeat like the Peasants' War. The Reformation as a continued early bourgeois revolution triumphed in 1536 with Calvin's Reformation in Geneva as the starting point for new developments, by helping a worldview appropriate to capitalism to break through. According to Ernst Engelberg, the Peasants' War was ultimately a “critical episode” and “turning point” (Engels) between the Reformations of Luther and Calvin and thus only the climax and stage but not the end of the first early bourgeois revolution .

The secularization of church property by the princes led, where it was carried out, to the departure of the feudal church as a pillar of the feudal system and part of the ruling class in the Protestant area of the Holy Roman Empire. The thus strengthened princes established themselves as rulers and pushed back the aristocratic particularism in their territories in favor of the central state. The estates with the state parliaments established in the late Middle Ages and the city citizens represented there lost their dominant position in the power structure to the princes by 1700. New institutions initiated by the state emerged and the superstructure took shape. In contrast to the Netherlands and England, absolutism fully expanded in Germany, while the productive forces lagged behind politically.

Early bourgeois revolution in the Netherlands

Initial social situation, agricultural structure

The process of capital accumulation also took place in the Netherlands. Like numerous early modern revolutions, it affected almost all strata of the population. There was no dichotomization of society, but a fragmentation of its groups and classes. However, the beginnings of manufacturing capitalism are the exception, not the rule. It mainly covered the textile industry with a considerable concentration of wage workers .

The provinces had a different agricultural structure. The basis was the rural allotment farms with one to five acres of land. The form of lease was very advanced. A stratum of wealthy peasants was formed who gradually became farmers of the commoners. The north of the Netherlands was hardly familiar with feudal ties, but in the south they still existed in some provinces, also in the form of serfdom. As a result, the farmers' interest in changing social relationships varied.

The positions of the feudal nobility were undermined on all sides. As a result of the price revolution, the fixed income from large estates fell sharply. Especially where the nobility did not succeed in converting the unprofitable money rents back into rents in kind. The nobility indebted themselves to the usurer and became impoverished. A considerable part of the land went into the hands of usurers, citizens or municipal institutions. For the time being, however, these new landowners granted the peasants their former feudal status, both legally and in terms of property. The feudal land ownership of the churches and monasteries did not decline; on the contrary, it increased threateningly, especially in the south.

The role of the peasants and their relationship to the urban petty bourgeoisie and the trading capital, nobility

Due to the high level of urbanization in the Netherlands, the cities and not the peasants were consequently at the center of the revolutionary movement. Compared to the German surveys, the Dutch peasant movement was less developed. The peasants supported the revolution more strongly at the beginning than at the end.

On the other hand, the peasant uprisings in Overijssel , Friesland , Drenthe , where the rebellious peasants, consciously or unconsciously, became accomplices of the feudal-Catholic reaction and Spanish agents were highly contradictory in nature .

Three basic causes determined the behavior of the peasantry during the uprising:

- The revolutionary uprising took place in the first phase of the manufacturing period, when neither objective nor subjective factors had reached the required degree of maturity, under the absolute predominance of commercial capital.

- Commercial capital had a purely "consumptive" interest in the agricultural sphere, namely a profitable investment of capital in land, the possibility of procuring agricultural products at low prices for export and raw materials for the branches of trade that it "controlled"

- The political alliance of the ruling merchant class with anti-Spanish, mostly Calvinist, but still feudal nobility of the Netherlands, also with supporters of the House of Orange , whose negative consequences were mainly passed on to the peasantry.

The lack of a solid political alliance between the urban plebeians and the peasantry, who, just like in the German Peasants' War, did not come to joint action and stood in each other's way. Neither the merchants, nor the Duke of Orange, nor the States-General worried about the urgent needs of the peasantry.

Overall, the Dutch struggle for freedom is a synthesis of different uprisings , which socially and historically cannot be thrown together. Accordingly, a bundle of motives for the survey is to be expected, which are composed very differently in the individual social groups , but also in accordance with the respective regional and local special conditions. Certain groups come to the fore in certain phases: from 1555 to 1566 the nobility , 1566 urban middle and lower classes, only a small part of the upper classes; after 1572 the upper middle class. There are more random factors, each for this were responsible: So for the intervention of the broad masses in 1566 economic conditions for the emergence of the bourgeoisie after 1572, the fact that the Geuseninvasion not in agrarian-aristocratic Friesland , but in civil Holland took place . In addition, the socio-historical shifts cannot be seen absolutely. The nobility played an important role until the end of the revolution. Sections of the lower nobility took part in the movements. In various places, they appeared as patrons of the hedge sermons , similar to their northern German peers .

Beginning of the uprising, bourgeois ideology

With Tridentine Catholicism and Calvinism , two church and belief systems confronted each other since the 50s of the 16th century, which in their constitutional norms and their spirituality represented suitable points of integration for the two different ruling elites within Dutch society. Hierarchical-centralistic Catholicism became the epitome of princely absolutism in the etatistic transformation by Philip II and the Spaniards . The presbyterialsynodische Calvinism on the other hand was compatible with constitutional norm, intellectual and social self-understanding of regional elites. The attribution and mutual effect of Calvinism, political freedom movement and capitalism to one another is not clearly possible.

The iconoclasm of 1566 had started the uprising. Similar to the German Peasants' War, this came from the lower classes. The mass mobilization in the context of the Calvinist "hedge sermons", which reached its symbolic climax in the famous iconoclasm of August 1566, were considered an expression of social and economic conflicts.

First of all, it is the coronation oath of the “ Joyeuse Entree ” of Brabant , which the early Dutch opposition invoked. It was a catalog of rights and duties of rulers and the ruled, linked to feudal law, the function of which was not to constitute rule, but to reaffirm a long-standing, quasi-natural relationship of rule. The Dutch resistance movement was still extremely careful not to exceed the legitimacy and legality framework established in this treaty. Even after the iconoclasm of 1566, the will of the Dutch Calvinists to cooperate with Philip II continued for some time. Likewise, the more moderate opposition under William of Orange tried to secure the legality and legitimacy of its anti-crown policy by means of historical precedents.

This led to the bloody joint suppression of the movement by the bourgeoisie, the nobility and the government. But continued in further contrast to the absolutism of republicanism by. The opposition could only preserve its chances against the rigid dictatorship of the Duke of Alba by decisively expanding its scope of action beyond the provisions of the Joyeuse Entree. As early as 1568, the armed uprising of the lower magistrates was justified in the spirit of Théodore de Bèze and later the “ Vindiciae contra tyrannos ”; The distinction between king and kingdom was also an integral part of the oppositional argument. The Treaty of Joyeuse Entree includes the rights and duties of rulers and ruled, but, linked to feudal law, this provided for a right of resistance.

Since 1574, the view prevailed that the estates, as the natural representatives of the people, are superior to the king. From 1579 after the publication of the famous "Vindiciae contra tyrannos" it was always emphasized that the princes were appointed for the benefit of the subjects and not the subjects for the benefit of the prince.

The uprising prevails, the States General - composed of the nobility and the bourgeois class - make up the government

The dictatorship of Duke Alba caused some of the farmers in the southern areas to form partisan armies of the Wald-Geusen , which found support from the local rural population. In the northern areas, rural seafarers and fishermen converted their guns into warships and added to the fleet of water geusen . After the outbreak of the uprising in 1572, the peasants from the northern provinces formed people's armies and fought against Spaniards and reactionaries. In 1578/79 a full-blown peasants' war raged in Flanders. The successful overthrow of the rebels during this period of uprising was due to the Reformed and the Wassergeusen. There was no broad front of the estates; each city acted in its own name in a very inconsistent insurgency movement, which was often associated with the replacement of the traditional elites and the establishment of new magistrates. With the upheavals, a new elite was established in the Dutch state assemblies, the Vroedschap , which was only partly made up of the traditional council.

The States General of all provinces met for the first time in 1576 without a call by the king under pressure from the Spanish Soldateska . The States General received new political powers. The States General, consisting of delegates from the self-governing organs, now exercised government. They consisted of the rural nobility colleges and the bourgeois magistrates. In the Plakkaat van Verlatinghe in 1581, the Geusen who had set the political upheaval in the first place no longer played a role. They were not taken into account in the new legitimation concept.

Between 1568 and 1609 the early bourgeois upper class had found a progressive solution to the feudal crisis and thus developed into the first state in Europe to survive the severe economic crisis of the 1640s without any internal difficulties.

English early bourgeois revolutions

English revolutionary leaders were John Ball , William Parmenter (successor to Jack Cade), Gerrard Winstanley , Robert Ket , Jack Straw , Wat Tyler , Jack Cade .

The traditional medieval opposition forms such as the local peasant uprisings against bondage and serfdom of the 15th century came from the first half of the actions of the poor peasants and small farmers against the entering into economic power burgeoisen circles and especially against the enclosures. Assuming that capitalization in England came from the countryside, the urban forms of opposition - with the exception of the events in London - had lagged behind the rural forms. From 1381 moderate and radical groups of forces emerged in the revolutionary movements, which expressed their specific class interests. In the Peasants' War of 1381, the moderate and radical factions appeared side by side.

The events of 1450/51 in south-east England were an important precursor to the later early bourgeois revolutions. However, the uprising did not yet form a closed ideology of the lower classes. Jack Cade led the Kent uprising in 1450. The real supporter of the revolutionary movement of 1450/51 that shaped England in the 15th century was not the broad class of free, self-employed peasants. The main driving force were impoverished peasants or farmers who had become landless due to the enclosures , the lower class of tenants, wage laborers in agriculture and the textile trade, and sailors. What is certain is that there were forces in the revolutionary movement of 1450/51 that were not satisfied with the “moderate” goal of Cade. The political claims of the anti-feudal camp had grown compared to 1381.

In England, in the first half of the sixteenth century, the conditions for a bourgeois revolution had grown. According to the English economic historian Richard Henry Tawney , social and property relations had been changing about a hundred years before the revolution began. The triggering of the revolution was prepared by the change in the social structure, which meant a structural crisis of the aristocracy, a breeding ground emerged that ultimately triggered the uprisings through random factors. The formation of manufacturing and the internationalization of trade were further economic side effects. After Marx and Engels, the new nobility and the bourgeoisie entered into an alliance against royalty, feudal nobility and the church. The absolute monarchy in the form of Tudor rule could no longer meet the changed demands of a bourgeoisie that had been openly pushing to power since 1588. Against the background of the containment movement, which led to the accumulation of capital and the release of labor, the central demands of the revolutionary forces included the breaking of guild fetters and the abolition of special privileges. The royal government and the politically impotent bourgeoisie cultivated a “non-relationship” that ultimately sparked the revolution.

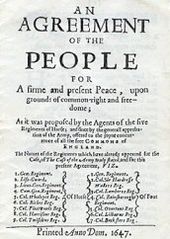

The revolution began with tax denial. With the end of the absolutist royal rule of Charles I through the convocation of the Short and Long Parliament and the beginning of parliamentary rule , a 38 year phase of domestic political disputes began in England. The civil war was fought between the monarchy, the church and large landowners on the one hand, and the middle class, in coalition with rural traders and the working class on the other. All of the factions involved had strong religious ties. Material conflicts of interest mixed with different cultural and religious beliefs. The conflict was exacerbated by intensifying trade in and between cities and the rapidly growing rural markets. These contributed to the fact that agrarian capitalist structures could spread. The puritanical-social conflict in the English countryside, between the aristocracy (landed gentry) and the peasantry, centered above all on the commercial value and use of rural property. Clear class boundaries and class antagonisms could not be made out in the revolution. The revolution produced a strong progressive movement from the lower strata of the population, whose spearheads were the assemblies of the soldiers' ranks in Putney . Radical organizations like the Levellers and Diggers also emerged from this turbulence. This radical movement was accepted by Cromwell and the rising capitalists as long as feudalism posed a threat to them. After the revolution, however, the middle class fought the radicalism of the lower classes, which became too dangerous for their interests. The execution of Charles I was followed by the phase of the English republic and the protectorate rule of Oliver and Richard Cromwell from December 1653 to May 1659.

Although Cromwell's troops also destroyed the mansions and castles of the nobility, the aristocratic privileges over land were not affected. Likewise, feudal jurisdiction over the residents of the lands of the nobility remained their prerogative. There were no general peasant surveys as at earlier times and neither were their demands for the abolition of tithes, access to the commons and the abolition of feudal official duties. Instead, the civil struggles for the rights of the individual to the development of the spirit and religion were formative. It was about urban autonomy.

With the restoration of the rule of the Stuarts in 1660, the revolutionary phase with its approaches to social reform ended. The English Revolution led to the division of the ruling class (formation of the new nobility), which made possible the Glorious Revolution of 1688, classified as a class compromise . England was the only country in Europe in which, according to the line of argument of the materialist dialectic, during the transition from feudalism to capitalism, not only a bourgeois but also a kind of “early bourgeois revolution from above” was decisive for the change of formation. This could happen because no such momentous setback to the development towards capitalism in the form of the defeat of the German Peasants' War had occurred on the British Isles. The re-establishment of the monarchy meant restoring the outward appearance of the old system, but Charles II had become king mainly because of the merchants and large landowners. Feudal laws and the old economic system lost their power.

The English bourgeoisie was given economic powers while at the same time the rule of the gentry , the wealthy rural and urban landowners, was inviolable . The agreement was based on the same interests of both social classes. The social or class compromise of 1688 determined the further development of the bourgeois-aristocratic mixed society of the British Commonwealth, following the logic of the arguments of the theories . It was a successful combination that gave the long-lasting alliance of democracy and capitalism a common foundation. The land-owning aristocracy recognized the possibilities and advantages of capitalism early on and from then on acted as a moderate political reformist. The great Whig families, who in the English aristocracy mainly represented the interest in money, determined the further course: foreign trade expansion. Continued in the parliamentary governments of a Robert Walpole or William Pitt . The Corn Bounty Act followed in 1689 , an export premium for grain that lasted into the 1770s. This raised grain prices and created production incentives. In terms of agricultural policy, this mainly meant the continuation of the enclosures. Large latifundia emerged that were operated through leases. From this, however, an agrarian capitalism developed . There was no longer any talk of peasant protection as it was under the Tudors . The farmers were the losers in this development. As a result, began the rural exodus of the poor landless small sounds in the industrial districts or emigrated.

The English Revolution has brought about lasting changes in the social and political life, thus the introduction of England freedom of trade in connection with freedom of movement and freedom of establishment found enforcement in the 18th century. As a result, the (early) bourgeois revolution in England helped manufacture capitalism to break through; the English bourgeois revolution created the political and social conditions for the industrial revolution of the 18th century. According to Christopher Hill , with the English Revolution, manufacturing capital ( production capital ) took precedence over commercial capital. In Schilfert's view , manufacturing capital already had the preponderance on the parliamentary side in the course of the first civil war from 1642 to 1646, compared to commercial capital, manifested in the party of the Independents.

In the assessment of the English revolution by Marx and Engels , the behavior of the English bourgeoisie stands out, which has shown itself capable of compromising with the revolutionary proletariat and ultimately asserted itself against feudalism and absolutism. This positive evaluation contrasts with the negative evaluation of the German bourgeoisie, which in the revolutionary struggle committed treason against the insurgent proletariat and from whom only the suppression of the proletariat is expected in the future. The ideas of the English Revolution fell on poorly fertile soil in the German cultural area. The level of social disputes was less developed and there was no New Nobility comparable to that in England. Germany had fallen behind in development from a capitalist point of view and the productive forces were less pronounced than in England. For Barrington Moore, Jr. , the Puritanically inspired revolution paved England's path to democracy , as well as establishing mediated techniques of rule. Capitalism arose on the basis of legality and peaceful order. From then on, the change was controlled.

Review

Only in the northern Netherlands and England was the new bourgeoisie (producers and commercial capital bearers) able to establish and assert itself politically against the traditional feudal forces during the 16th and 17th centuries. In the Holy Roman Empire, on the other hand, the upper bourgeoisie did not form an organized, interest-based social class , but remained fragmented and politically impotent. This first phase of the bourgeois revolutions, which ended with the English Revolution, had only achieved spread and durability on the north-western fringes of Europe. The feudal class was able to hold its own in the remaining part. However, their internal composition suffered a loss of substance. In particular the lower nobility lost influence, power and economic resources. The top of the nobility, on the other hand, was able to stay at the top of the social pyramid. The widespread implementation of the bourgeoisie as a socio-political force , stratum and class did not take place in continental Europe until the French Revolution and in the German Confederation at the earliest from the revolutions of 1830 , 1848/9 but actually only with the high industrialization and formally and legally with the November Revolution 1918, the results of which annulled the nobility as a separate political force.

Concept history

The societies of that time were not yet civil societies, not even the Dutch. The characterization as an early form of a bourgeois revolution takes into account a non-existent secularized society in which the movements respected and subordinated themselves to the religious foundations of society and the dominance of the church system. On the other hand, it was the beginning of the transformation process from feudal to bourgeois society, which limited the scope of structural changes.

To solve this conceptual problem, the Eastern European historians in particular introduced a distinction between bourgeois and early bourgeois revolutions in the conceptual apparatus of the historical sciences.

The term was initially adopted in the specialist literature without any further justification. It was only when Soviet historians began a debate about the character and historical location of the Reformation and the Peasants' War in 1956 that attempts were made to define its content more precisely. Max Steinmetz kicked it off in 1960 . The concept has since changed considerably as a result of internal Marxist debates influenced by international reactions. Ultimately, the term in modern Marxist sociology has partially replaced the term used by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels of the bourgeois revolution for this type of revolutionary movement.

The meaning of the term system “early bourgeois revolution” experienced several modifications within the Marxist-Leninist reference system. This technical evolutionary process was initiated by the turning of socialist historical science to a comparative, world-historical-dialectical approach. Along with this, the once prominent position of the German Peasants' War was downgraded in the context of European developments. Instead of a narrow national historical perspective, an international approach now dominated. The graduation from feudalism to capitalism also experienced a greater differentiation. Every new early bourgeois revolution now had the task of weakening feudalism according to the starting level and degree of development of society. The overcoming of the feudal order as the highest goal of every early bourgeois revolution was no longer defined as a decisive criterion, but only the weakening of the feudal order.

The concept was initially ignored or rejected without discussion by non-Marxist historians, but eventually accepted as a challenge to reflect on counter-concepts. Western historians working on this were Winfried Schulze , Peter Blickle , and Rainer Wohlfeil . The debate was not continued after the 1989 "turnaround".

The embedding of the early bourgeois revolutions in the Marxist-Leninist overall concept of the theory of revolution by socialist historians met with criticism in Western cultures at the same time . The main objection of Western historians was that in the 16th century there were no objective constraints, or the subjective possibility of establishing a bourgeois capitalist social order.

Again, Western historians criticized the general Eastern concept of history, which was used to justify national power politics and therefore did not define its own independent ideals of knowledge , but was given them as a guiding value by politics. Historical research on the early bourgeois revolution thus had a determining, politically affirmative character from the start. The technical problems arising from this, such as the incompatibility of one's own guiding principles with historically contradicting processes, could therefore never be resolved with scientific methods, at best with ideological blinkers and self-imposed thinking bans . In technical terms, the Marxist-Leninist history was asked to modify its conception further. For example, to provide empirical findings for your claims and to revise the chain of arguments where you cannot find them. This applies above all to the sensitive area of the “burgeoisie” group, which has remained vague and indefinite. Corresponding historical social studies were therefore not conclusively available.

The bourgeois historical scholarship does not have to offer its own comparable concept of historical theory, comparable to the feudalism-capitalism concept. Your generalizations are on the inductive way of abstraction from the source study won. Comprehensive explanations are not available. Because of their small-scale structures, overarching relationships are neglected by bourgeois historiography . Coherent considerations of agricultural history as well as urban history or cross-epochal contexts have so far only rarely come into focus.

As a result of the discourse up to 1990, the theory is still not considered verified or falsified . It is still being advocated with great effort by part of historical science . For traditional historical studies, the theoretical model of the early bourgeois revolutions remains a model with heuristic value. Scientifically, it is still up for discussion alongside other explanatory models and interpretations. Marxist historians criticized the lack of consideration for the social perspective of the bourgeois representatives and accused them of completely suppressing the social revolutions in their historiography . Due to the many mutual accusations that the Cold War confrontations carried over into science, the approach has ultimately been a continued ideological battleground on paper, in which both sides, consciously and subconsciously, thought and wrote first in a camp-oriented manner and only then based on knowledge. Both sides wanted to legitimize their own side and delegitimize the other side.

literature

- Josef Foschepoth : Reformation and Peasants' War in the history of the GDR. On the methodology of a changed understanding of history . Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1976

- Ines Jachomowski: Peasants' War and the early bourgeois revolution in the history of the GDR , GRIN Verlag, 2007, ISBN 9783638801041

- Klaus Vetter : The Dutch early bourgeois revolution 1566–1588, Berlin 1989.

Web links

- Lemma entry in the online lexicon of the Mennonite History Association

Individual evidence

- ↑ Laurenz Müller: Dictatorship and Revolution: Reformation and Peasants' War in the historiography of the Third Reich and the GDR, Lucius & Lucius Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, p. 255

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 44

- ↑ Yearbook for the History of the Socialist Countries of Europe, Volume 21, Edition 2, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1977, p. 140

- ↑ Yearbook for the History of the Socialist Countries of Europe, Volume 21, Edition 2, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1977, p. 118

- ↑ Yearbook for the History of the Socialist Countries of Europe, Volume 21, Edition 2, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1977, p. 127

- ^ Stefan Breuer: Social history of natural law, Volume 42 of contributions to social science research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 236

- ↑ Werner W. Ernst: Legitimationswandel und Revolution, Volume 49 of Contributions to Political Science, 1986, p. 41

- ^ Stefan Breuer: Social history of natural law, Volume 42 of contributions to social science research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 238

- ^ Stefan Breuer: Social History of Natural Law, Volume 42 of Contributions to Social Science Research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 239

- ↑ Stefan Breuer: Social history of natural law, Volume 42 of contributions to social science research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 246

- ^ Stefan Breuer: Social history of natural law, Volume 42 of contributions to social science research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 247

- ↑ Alexander Fischer, Günther Heydemann: History in the GDR: Pre- and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 213

- ↑ Alexander Fischer, Günther Heydemann: History in the GDR: Pre- and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 217

- ↑ Martin Roy: Luther in the GDR: On the change in the image of Luther in GDR historiography; with a documentary reproduction, Volume 1 of Studies on the History of Science, Dr. Dieter Winkler, 2000, p. 195

- ↑ Laurenz Müller: Dictatorship and Revolution: Reformation and Peasants' War in the historiography of the Third Reich and the GDR, Lucius & Lucius Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, p. 240

- ↑ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 284

- ↑ Sverker Oredsson: Geschistorschreibung und Kult, Volume 52 of Historische Forschungen Series, ISSN 0344-2012, Duncker & Humblot, 1994, p. 235

- ↑ Peter Heinz Feist, Ernst Ulmann, Gerhard Brendler: Lucas Cranach: Artist and Society: Referate D. Colloquiums With Internat. Participate. For the 500th birthday of Lucas Cranach D. Ä., Staatl. Luther Hall Wittenberg 1.-3. October 1972, Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1973, p. 50

- ↑ Journal of History, Volume 28, Issues 7-12, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1980, p. 1070

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 53

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 12

- ^ Heinz-Elmar Tenorth: History of the University of Unter den Linden 1810-2010: Practice of their disciplines. Volume 6: Self-Assertion of a Vision, Walter de Gruyter, 2014, p. 344f

- ↑ Alexander Fischer , Günther Heydemann : History in the GDR: Prehistory and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 211

- ↑ Laurenz Müller: Dictatorship and Revolution: Reformation and Peasants' War in the Historiography of the 'Third Reich' and the GDR, Volume 50 of sources and research on agricultural history, Walter de Gruyter, 2016, p. 176

- ↑ Stefan Breuer : Social history of natural law, Volume 42 of contributions to social science research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, pp. 243f

- ↑ Alexander Fischer, Günther Heydemann: History in the GDR: Pre- and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 213

- ^ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 79

- ^ Stefan Breuer : Social History of Natural Law, Volume 42 of Contributions to Social Science Research, Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 240

- ^ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 71

- ↑ Alexander Fischer , Günther Heydemann : History in the GDR: Prehistory and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 203

- ^ Walter Zimmermann: The Reformation as a legal-political problem in the years 1524-1530 / 31, Kümmerle-Verlag, 1978, p. 149

- ↑ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 126

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 255

- ↑ Alexander Fischer, Günther Heydemann: History in the GDR: Pre- and Early History to the Latest History, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 192

- ↑ Susanne König : Life in Extraordinary Times: Medieval Research and its Representatives at the Humboldt University in Berlin in the GDR, Volume 161 of History, LIT Verlag Münster, 2018, p. 276

- ↑ Heinz Schilling: Selected Treatises on the European Reformation and Denominational History, Volume 75 of Historical Research, Duncker & Humblot, 2002, p. 304

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 11

- ^ Journal of History, Volume 28, Issues 7-12, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1980, p. 1067

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 54

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 50

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 55

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: 200 Years of the American Revolution and Modern Revolution Research, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1976, p. 202

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: 200 Years of the American Revolution and Modern Revolutionary Research, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1976, p. 195

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: 200 Years of the American Revolution and Modern Revolutionary Research, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1976, p. 227

- ^ Heinrich Lutz: Reformation und Gegenreformation, Volume 10 of Oldenbourg Grundriss der Geschichte, 5th edition, Oldenbourg Verlag, 2010, p. 162

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: 200 Years of the American Revolution and Modern Revolution Research, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1976, p. 192

- ↑ Werner W. Ernst: Legitimationswandel und Revolution, Volume 49 of Contributions to Political Science, 1986, p. 48

- ^ Richard Saage: Political Thought Today: Civil Society, Globalization and Human Rights: Historical-Political Studies, Volume 143 of Contributions to Political Science, ISSN 0582-0421, Duncker & Humblot, 2007, p. 41

- ^ Richard Saage: Political Thought Today: Civil Society, Globalization and Human Rights: Historical-Political Studies, Volume 143 of Contributions to Political Science, ISSN 0582-0421, Duncker & Humblot, 2007, p. 42

- ↑ Richard Saage: Dominion, Tolerance, Resistance, Suhrkamp, 1981, p. 37

- ↑ Katharina Graupe: Oratio historica - Speeches about history: Investigations into practical rhetoric during the Spanish-Dutch conflict in the 16th and 17th centuries, Volume 156 of early modern times, Walter de Gruyter, 2012, p. 175

- ↑ Katharina Graupe: Oratio historica - Speeches about history: Investigations into practical rhetoric during the Spanish-Dutch conflict in the 16th and 17th centuries, Volume 156 of early modern times, Walter de Gruyter, 2012, p. 176

- ^ Günter Berghaus: Studies on German Literature, Volume 79, M. Niemeyer, 1984, p. 164

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 75

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 77

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 74

- ↑ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 295

- ^ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and in German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 289

- ^ Andreas Hess: Sociopolitical Thinking in the USA: An Introduction, Elements of Politics, Springer-Verlag, 2012, p. 103f

- ↑ Mark Teufel: The silent coup: Thailand 2008, 2009, p. 44; There: reproduction of an essay by Christopher Hill : The English Revolution 1640, 1959

- ^ Pyotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin : The French Revolution, Jazzybee Verlag, 2016, p. 63

- ^ Siegfried Hoyer: Reform, Reformation, Revolution: Selected contributions to a scientific conference in Leipzig on October 10 and 11, 1977, Karl Marx University, 1980, p. 255

- ↑ Mark Teufel: The silent coup: Thailand 2008, 2009, p. 44; There: reproduction of an essay by Christopher Hill : The English Revolution 1640, 1959

- ↑ Manfred Kossok, Werner Loch: Peasants and the bourgeois revolution - studies on the history of the revolution, Topos, 1985, p. 16

- ↑ Otto Hintze: Sociology and history: collected treatises on sociology, politics and theory of history, The Dt. Königspfalzen / Deliveries, Volume 2 of Collected Treatments - Otto Hintze, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1982, p. 444.

- ↑ Otto Hintze: Sociology and history: collected treatises on sociology, politics and theory of history, The Dt. Königspfalzen / Deliveries Volume 2 of Collected Treatments - Otto Hintze, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1982, p. 439

- ^ Ernst Engelberg: Problems of Marxist History: Contributions to their theory and method. Pahl-Rugenstein, 1972, p. 146.

- ^ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and in German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 301.

- ^ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and in German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 286

- ↑ Roland Ludwig: The Reception of the English Revolution in German Political Thought and German Historiography in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2003, p. 9

- ^ Andreas Hess: Sociopolitical Thinking in the USA: An Introduction, Elements of Politics, Springer-Verlag, 2012, pp. 103-105

- ↑ Article by Günter Vogler

- ↑ Marcel van der Linden , Bert Altena: The Reception of Marx's Theory in the Netherlands, Volume 45 of the writings from the Karl-Marx-Haus , Karl-Marx-Haus , Trier 1992, p. 40.

- ^ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 101

- ↑ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 99.

- ^ Josef Foschepoth: Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image, Duncker & Humblot, 1976, p. 15

- ^ Peter Blickle : Unrest in the corporate society 1300-1800. Encyclopedia of German History, Walter de Gruyter, 2010, p. 100.

- ↑ Alexander Fischer , Günther Heydemann : History in the GDR: Prehistory and early history to the latest history, Volume 2 of History in the GDR, Duncker & Humblot, 1990, p. 207

- ↑ Laurenz Müller: Dictatorship and Revolution: Reformation and Peasants' War in the historiography of the 'Third Reich' and the GDR, Volume 50 of sources and research on agricultural history, Walter de Gruyter, 2016, p. 174

- ↑ In another example, a Marxist historian congratulated a professionally inclined West colleague for having put a Marxist cuckoo egg in a bourgeois manual. in: Musicology and the Cold War: the example of the GDR, Nina Noeske, Matthias Tischer (ed.), Volume 7 of KlangZeiten - Music, Politics and Society, Böhlau-Verlag, Cologne Weimar, 2010, p. 23