Stalhof

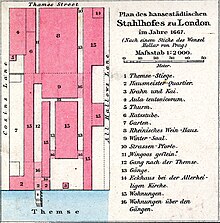

The Stalhof (also Stahlhof ) has been a fenced off approximately 7000 m² area on the north bank of the Thames since 1475 , on which the Hanseatic merchants in London had their branches. In 1853 the area was sold by the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg. The Stiliard (Steelyard) was bordered by Cousin Lane in the west, Thames Street in the north and Allhallows Lane in the east. Since the Cannon Street station was opened in 1866 , the track system to the Thames Bridge has been on the property.

Guildhall

Since the early 11th century, Rhenish merchants can be found in London who mainly traded in wine . In 1175 some Cologne merchants obtained trade privileges or letters of protection through Heinrich II and founded a joint branch on the Thames. This building, the Guildhall , translated as guild or guild house, served the merchants of the merchants as a meeting place, warehouse and occasionally for residential purposes.

Around 1238 and 1260 Heinrich III. the privileges of the merchants confirmed, they now applied to all German Hanseatic merchants in London. The main commercial goods of German merchants changed, and instead of wine there was mainly grain and cloth that were imported into England .

Stalhof

In the 15th century, the aspiring English trading bourgeoisie tried more and more to break the Hanse's prerogatives in Baltic trade . When English ships were seized and confiscated in the Sound in 1468 with the help of Danzig capers chartered by the Danish Crown, Edward IV had the Guildhall storm and plundered in the spring of 1469. The merchants were temporarily imprisoned and had to be liable for the damage caused in the sound with their property. That was the occasion for the Hanso-English War , which ended with the Peace of Utrecht (1474) and confirmed the rights of the Hanseatic League. After this peace agreement, the area adjacent to the Guildhall was given to the merchants by the English king. This area was surrounded with a strong wall and called Steelyard or Stalhof. The site had its own crane , its own farm and residential buildings, and a garden. Since the revocation of trade privileges in 1552 by King Edward VI. Heinrich Sudermann from Cologne , from 1556 to 1591 syndic of the Hanseatic League, also tried diplomatically with Edwards' successors to stabilize and save the Stalhof for the Hanseatic League. When the conflict over cloth exports increased at the end of the 16th century and England was at war with the German Emperor, Queen Elisabeth ordered the expulsion of the Hanseatic merchants from England on January 13, 1598 with effect from January 24, whose trade privileges she revoked, as well the closure and confiscation of the Stalhof. The reason was the expulsion of the English Merchant Adventurers from Stade , which took effect on the same day . In 1606 the Stalhof was returned to the previous Hanseatic owners, but the privileges were not renewed. In the following years it had hardly any economic significance. Most of the buildings were destroyed in the great fire of London in 1666. They were rebuilt at the expense of the cities of Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck. They partly used the building for their own purposes and had the Stalhof administered by the Stalhofmeister. For a time, these three cities in London also had their own joint diplomatic chargé d'affaires , mostly as consul general and ministerial resident like the Scottish Patrick Colquhoun († 1820). The last Stalhofmeister in London was the Hanseatic Prime Minister James Colquhoun († 1855). Two years before his death, the legal successors of the Hanseatic League, Lübeck , Bremen and Hamburg , sold the site for good in 1853.

At the head of the Stalhof stood the elderly man elected by the merchants on New Year's Day , as well as two assessors. The elderly man represented the Stalhof externally, ensured that internal regulations were enforced and was the court lord. The office statutes of the Stalhof required that one of these elected men should represent one of the following regions, called thirds . The first third refers to Cologne and other cities on the left bank of the Rhine. The second third comprised the cities on the right bank of the Rhine, Westphalia , Saxony and Wendish . Merchants who were supposed to represent the last third had to come from Gotland , Livonia or the Prussian cities of Danzig and Elbing . Since the Cologne merchants were always in the majority in the Stalhof, they usually provided the senior man. The Stalhof was mainly financed from a levy called " Loss ", which all Hanseatic merchants who traveled to England had to pay.

The Stalhof was superior to the other Hanseatic branches in England, such as those in Boston or King's Lynn . The warehouse buildings of the Hanseatic factory still preserved in Lynn give an idea of what the Stalhof might have looked like.

The work carried out for the Stalhof and its members also belonged to the time of Hans Holbein the Younger's second stay in England : portraits of at least five merchants, including the famous Georg Gisze from 1532, allegorical monumental images (triumphal procession of wealth and poverty, 1532 / 1535), festive decorations and designs for silver work. Apart from these portraits, with the exception of a silver jug with a basin based on a Holbein design, no pieces of equipment or architectural remains have survived. But there are detailed descriptions of the Stalhof by the London city biographer John Stow .

Elderly people

- Tideman Berck from Lübeck (1486)

Stallion Master

- James Colquhoun , last stalemate

Name theories

There is no agreement on the origin of the name. According to one thesis, it is derived from Middle High German and Old High German stal , Dutch stal , English stall , Swedish stall , which originally meant place, stand, location . More recent research suggests, however, that the Low German verb stalen , which means something like "seal with the help of a steel stamp", led to the name of the branch. In archaeological excavations, for example, many cloth seals were found that were used for customs clearance of cloth or as a seal of origin. Since the 14th century, there have been many cloth-processing professions in the vicinity of the Stalhof.

literature

- Johann Martin Lappenberg : Documented history of the Hanseatic steel yard in London . Langhoff'sche Buchdruckerei, Hamburg 1851.

- Wolfgang Rosen / Lars Wirtler (ed.): Sources on the history of the city of Cologne. Vol. I. Cologne 1999, p. 148: Protection for Cologne merchants in England: The first mention of the Gildehalle ("Stalhof") in London in 1176.

- The Hanseatic Reality and Myth. Exhibition catalog volume 1. Hamburg 1989.

- Nils Jörn: "With money and bloode". The London Stalhof in the area of tension in Anglo-Hanseatic relations in the 15th and 16th centuries. (= Sources and representations on Hanseatic history; N. F., Volume 50). Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2000. ISBN 3-412-08800-5 .

- Theodor Gustav Werner: The Stalhof of the German Hanseatic League in London in economic and art-historical images. In: Scripta Mercaturae. 1/1973, ISSN 0036-973X .

- Theodor Gustav Werner: The Stalhof of the German Hanseatic League in London in economic and art-historical images. A continuation. In: Scripta Mercaturae. Issue 1/2 1974, pages 137-204.

- Theodor Gustav Werner: Appendix to the history of trade and traffic on the Stalhof from the second half of the 16th century. until the 18th century. In: Scripta Mercaturae. 1/1975, pages 91-105.

- Katrin Petter-Wahnschaffe: Hans Holbein and the Stalhof in London. Berlin / Munich 2010, pp. 29–48.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The wording of the order of January 13, 1598 (English).

- ↑ Petter-Wahnschaffe, pp. 161–164.

- ↑ The basin from the Bremen town hall in the Focke Museum Bremen is the only silver work that can be traced back to a Holbein design with verifiable proof of provenance at the Stalhof.

- ^ Karl Schiller and August Lübben: Middle Low German Dictionary , Vol. 4, 1878 (also reprinted 1969), pp. 355–357.

Coordinates: 51 ° 30 ′ 41 ″ N , 0 ° 5 ′ 26 ″ W.