Baltic trade

The Baltic Sea trade in the Baltic Sea region describes the historical and current profit and performance-oriented exchange activities of the people and groups of people living or working there from the Middle Ages to the present day.

It was not until the late Middle Ages that the area experienced a noticeable manorial densification and the emergence of larger urban centers . For this reason, the Baltic Sea trade has long been understood in modern historical research as a peripheral European event horizon (in contrast to this is the Mediterranean trade ). However, this past assessment changes with increasing intensification of research activities. According to Michael North , the Baltic Sea was the hub of the world economy in the early modern period . The early modern Baltic Sea trade was based on the exchange of food and raw materials from the resource-rich Northern and Eastern Europe for finished goods from the industrially highly developed north-west Europe . The Baltic Sea linked different regions of the world and was the core of profitable exchange relationships. These were systematically interwoven and integrated into European trade .

Viewing levels

Socially

In the modern sense of the word, trade encompasses many other forms of human exchange in addition to the act of transport, i.e. the transport of material goods from the producer to the trader to the buyer. Fundamental for this is the direct or indirect corporate or individual profit -making intent . This includes:

- Intangible, but performance-oriented forms of exchange such as interpersonal or interorganizational knowledge transfer

- Exchange of immaterial rights of disposal

- Logistics processes in the broader sense, including trade fairs, congresses, marketing and sales organizations, but also the classic markets

- Infrastructure and modes of transport

- the financial industry, stock exchanges, investments, and general speculation

- in a broader sense also tourism and all forms of organized personnel relocations with the intention of making a profit, e.g. B. Individual border trade (Finnish spirits tourism in Estonia, Poland markets, etc.)

- Government action and research activities in cross-section on economic relations

Geographically

Economic clusters, spatial planning, network relationships, cooperation models, global interdependencies and constellations of actors are fundamental dimensions of trade.

There is and has been trade outside the Baltic Sea, i.e. the exchange of goods from a place in the Baltic Sea region to a place outside the Baltic Sea region, and trade within the Baltic Sea. The minimum definition for trade in the Baltic Sea provides either the geographic origin of a transaction or a geographic (intermediate) destination within the Baltic Sea region.

Historically, the inland areas of the Baltic Sea trade reached as far as ship-worthy tributaries made inland shipping possible. In the south this influence only ended south of the Oder. The centers of Breslau , Frankfurt an der Oder ( Frankfurter Messe ), but also Warsaw, Leipzig (Leipziger Messe, Via Imperii ), the Altmark, the Havelland and also the Elbe shipping are historically part of the economic area of the Baltic Sea region.

Artificial waterways have steadily expanded this sphere of influence.

Political-historical

Supranational associations such as today's European Union , but also the Hanseatic League , created political economic areas. Personnel and real unions such as Saxony-Poland or Poland-Lithuania led to the establishment of economic ties that were stable for centuries and continue to have an effect today.

Transformations of power in the Baltic Sea region and effects on trade in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea region was and is a zone of diverse exchange relationships. Various linguistic communities - Germans , Slavs , Balts and Finns - have lived there since ancient times, and they developed into peoples and states in the Middle Ages, but in some cases only in the modern era . Despite the very different neighbors, the uneven economic development and the different geological and climatic conditions, the Baltic Sea region formed an interconnected historical landscape early on . Only gradually did the Baltic Sea region and its territories also become the scene of political and armed conflicts. Ecclesiastical, economic and cultural networks became more concentrated due to the easily manageable contacts.

In the course of the Christianization of the once pagan, long-established population groups of the Prussians , Livs , Latvians and others, their lands were taken over by German crusaders and settlers until 1212. Territories were assigned to the Teutonic Order to form its own secular state. German merchants founded Reval, the Order of the Brothers of the Swords prevailed over the Danes in Estonia. Further German and Scandinavian attempts at expansion ended on the Neva in 1240 and on the Peipussee in 1242 . The cities of Livonia with the commercial German upper class and a city council that emerged from it at the top belonged almost all to the Hanseatic League. From then on, this part of the Baltic Sea belonged to the Christian and western dominated West .

In the course of the early modern hegemonic struggles, also known as the Nordic Wars , for the Dominium maris baltici , the state affiliation of individual coastal countries was subject to frequent changes over the course of history. Various powers gained control of the Baltic Sea or at least parts of the coast for longer periods, for example the Swedish Empire in the 17th century. These lordly empires mainly controlled the transit of narrow sea areas such as the Sound and thus had important income at their disposal, with the Sound Customs being the decisive financial factor. The grain trade was decisive in the early modern period. He mainly went to the highly urbanized Netherlands and secured their supply.

At the same time, the Baltic Sea region was the scene of an intensive exchange on all levels of social and cultural life. The intensification of communication with the help of shipping and trade as well as the migration of groups of people promoted transformation processes, some of which ran counter to developments in the state. This is how supranational cultures emerged, such as those of the Vikings and Slavs ( Kievan Rus , Novgorod Republic and others) or the Hanseatic League . The Dutchification in 16/17. Century as well as the Sovietization in the 20th century shaped the Baltic Sea area.

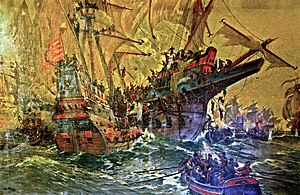

Denmark, Sweden, and Russia built and maintained large war fleets to protect their maritime interests and territorial integrity. Between 1500 and 1800, the area was also a frequent scene of major naval battles . Sweden was able to completely dominate the sea and trade in the 17th century due to its fleet as " Mare Nostrum ". However, it lost this status to Russia after 1700 and henceforth declined to a secondary power.

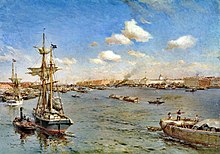

After 1800, the Baltic Sea region went through various changes in perception. In the 18th century, Russia intensified its rule in the newly won Baltic Sea provinces of Ingermanland , Swedish Estonia , Livonia and Courland . With Saint Petersburg a " window to the west " was created, through which most of the exchanges with the European west took place from now on. Russia, the new Nordic great power, tried from then on geopolitically to establish a Nordic system . This was followed in the 19th century by a long Russian-dominated calm in the north , which lasted until the First World War and which preserved the character of the Baltic Sea as a quasi-Russian inland sea . The National Socialist historian Erich Maschke designed the picture of a Germanic Baltic Sea region . The Soviet occupation of the Baltic states and their incorporation into the Soviet Union in 1940, as well as the loss of most of the German territories on the Baltic coast, reduced general interest in this region, which was mainly kept alive by emigrants and homeland associations.

The political upheavals of 1989, which gave the region a new meaning, were decisive. Finns and Estonians noticed each other more. The scientific exchange between Germany and the countries bordering the Baltic Sea revived sustainably. In 1988, Schleswig-Holstein opened the debate about a New Hanseatic League , which, based on the city council of the Middle Ages, was supposed to put cooperation between the Baltic states on a new basis. This was followed by cultural initiatives such as the Ars Baltica art exhibitions and the Jazz Baltica music festival . This was made possible by the political events of 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union . This changed the perception of the room once more. Cities and countries that had been considered distant, unknown and foreign were discovered in the neighborhood and, despite the visible economic decline, perceived as culturally similar. At the same time, politicians designed the Baltic Sea region as a future region. The Scandinavian states in particular (where only Denmark belonged to the EU ) feared being overtaken and marginalized by the dynamism of the European unification process. Therefore, the Baltic Sea founded at the initiative of the Danish and German Foreign Minister Uffe Ellemann-Jensen and Hans-Dietrich Genscher in 1992 the CBSS inspired, the cooperation in the political field significantly intensified through meetings of prime ministers, foreign ministers and parliamentarians and the work of countless subcommittees and NGOs. With the membership of all the countries bordering the Baltic Sea as well as Iceland in the west, the Baltic Sea was once again - this time politically - redefined. The eastward expansion of the EU since 2004, through which now all the countries bordering the Baltic Sea with the exception of Russia belong to the European Union, and the proclamation of the EU strategy for the Baltic Sea area in 2009 changed the image of the area again. The Baltic Sea Region strategy, which focuses on the environment, economy, security and accessibility, aims to turn the Baltic Sea region into a model region for regional cooperation in the EU. This includes constructions of the Baltic Sea region as a mission, trade, rule and cooperation or future region (s).

The renewed political interest has given the Baltic Sea area research significant impetus.

Effects of trade in exchanges

One medium of cultural exchange was trade, without which neither the material nor the immaterial transfers of the interacting cultures could have been carried out. Merchants were the first to cross the sea, and the goods they brought changed declining societies and cultures as did the importance of goods in the exchange process. The exchange across the sea also influenced the mentalities of merchants, their trading partners, and buyers and consumers. Craftsmen, artists and scholars took up the new ideas, processed them and passed them on, provided they had not communicated them from one Baltic coast to the other themselves. Coasts and port cities were close enough to connect and far enough to separate. The population in the hinterland of the coast did not cross the sea themselves, but was affected by the consequences of contact as producer and consumer. At the same time, economic exchange laid the basis for the development of states, which in turn sought to subjugate trade.

Historical commercial products

Tar extraction in the forests of Sweden, before 1824

Washing out work on the lake for the extraction of iron ore , Sweden 1897

Amber fisherman Amber graves. Samland coast, 1677

Furrier tanning his skins (Russia, 1896)

Imported Chinese porcelain

Historic water sawmill in Sweden for the production of z. B. of ship planks

Dutch herring fleet around 1700, with a warship of the Dutch Navy as an escort

Herring preservation in Amsterdam, 17th century

medieval forest honey production in Russia

History of the Baltic Sea Trade

Ancient trade

Already since 500 BC The amber trade in the Baltic states with the Mediterranean region is documented. The Amber Route began on the Prussian coast near the Baltic Prussians , led up the Vistula , through the Moravian Gate , over the Semmering Pass, over the Alps and finally to Aquileia on the Adriatic Sea, from where the goods were shipped to Egypt . The amber trade flourished between 100 and 500 AD.

Trade in the Early Middle Ages and during the Viking Age

The pirates of the Estonian islands became notorious. The Semgaller and cures were the Seeräubreei after. The Viking Age began around 600 and was attracted by merchants for their raids. Coin finds prove trade contacts as far as Arabia.

For the Vikings around 800 AD, the Baltic Sea region still offered great opportunities for expansion and accumulation of wealth. As early as the 8th century, furs from the East were a coveted commodity on the western markets. In the following years, the resources of the East were to be systematically developed. This happened mainly through the Svear , who are called Rus' or Varangians in the Slavic sources . Via Don , Volga or the Caspian Sea they reached the Arab world where they traded or stolen large amounts of silver ( route from the Varangians to the Greeks ).

Arabic sources report:

“They go on forays against the Slavs with ships until they get there, capture them and bring them to the capital of the Khazars , Bolgar , to sell them there. They have no fields of crops, but only eat what they export from the Slavic lands. Their employment consists of trading in sables , squirrels and other furs. They sell these furs to their customers and in return receive a hidden fortune in coins that they tie into their belts. "

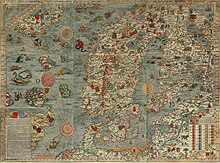

The trading room was structured by creating permanent trading places. These were multi-ethnic. The following trading zones were structured:

- the area of the western Baltic Sea with Skåne

- the southern Baltic coast to the mouth of the Oder

- the region between the eastern mouth of the Oder and the mouth of the Vistula including Courland and the islands of Gotland and Öland opposite

- the area between central Sweden and the Gulf of Finland

These four zones were also connected to one another.

The actors in trade were shipbuilders, traders, craftsmen, and sometimes slaves as living goods. Also Friesen , Anglo-Saxons , Arab and Jewish merchants took part in the Baltic trade. Jews established contact with the Arab world and spread news there about the Baltic Sea region.

At that time, the largest trading centers were Haithabu on the Schlei , which was ruled by the Vikings , located at the interface between the Baltic and North Sea, Reric on the Wismar Bay , Wolin ( Vineta ) on the Oder delta , Truso in the Vistula delta , Birka in the Mälaren lake , the island of Gotland and Staraya Ladoga in Russia, which represented the hinge to the Black Sea trade. There were also a number of smaller and temporary trading centers such as Menzlin on the Peene or Ralswiek on Rügen . There, too, the population was mixed multiethnically between Vikings and Slavs.

The Anglo-Saxon traveler Wulfstan von Haithabu reported about other trading centers of the Vikings . Truso existed in Prussia . Other Viking trading settlements , so-called Kaupang , which stands for “Kaufhafen”, were Sciringes heal , Birka in Sweden or Staraja Ladoga in Russia. The trips of Wulfstan and Ottar prove to posterity that the trade routes of the Baltic Sea were already open to English and other traders at this time and that the area as a whole was already a highly frequented trading region.

Haithabu had a port with jetties and jetties . Trading took place on these. The range of trade was great. Cloth from Friesland, ceramics , glass , weapons from the Rhineland, millstones from the Eiffel, mercury and tin from the Iberian Peninsula or England. Soapstone , whet slate and iron came from Scandinavia , while amber came from the eastern Baltic Sea.

The trading center Birka in Lake Mälaren played an equally important role in the Baltic Sea trade. A royal official kept the local craftsmen and foreign merchants in order. The place was also exposed to raids by Danish Vikings. The island of Gotland took over its important mediating role in east-west trade around the year 1000, whose peasant merchants did not settle permanently in Russia, like the Svear, but only traded seasonally and kept returning to their island. Most of the silver in circulation in the Baltic Sea region was hoarded here. The coins came increasingly from Western Europe, especially from German mints (see Viking Age coin finds in the Baltic Sea region ). The transition from regular trade to piracy was fluid, and slave trade was widespread. Regular trading goods were grain, horses , honey , wax , furs and amber, in addition to the goods from Western Europe already mentioned, such as weapons, cloth and millstones. There was also local and regional commercial production such as combs and salt. Based on the evaluation of the coin finds in the region, a positive trade balance of the Baltic Sea area compared to the North Sea area is assumed. Since the end of the 10th century, the flow of coins for Arabic silver has slowly dried up. The silver movements were reversed and as trade contacts with England became more intensive, English pennies flowed into the Baltic region in large numbers.

The Viking trade had already peaked in the 11th century. On the one hand, the step state formation with the formation of strong dynasties ahead, on the other hand silted many original ports or even sank. After 200 years, the Viking trade network collapsed. New trading locations such as Danzig, Polotsk an der Düna, Reval, Dorpat, Lund , Helsingborg , Roskilde , Uppsala , Söderköping and others emerged.

Starting position before the strength of the German Hanseatic League

Visby on Gotland became the largest trading center in the Baltic Sea region. The city was founded shortly before 900 on the west coast of Gotland, but remained outside the center of Gotland trade for a long time. The Gotland long-distance traders instead lived all over the island on their farms; although they often owned their own ships, they remained farmers alongside them. From 1160 Visby formed its own republic. At the time, Danes, native Swedes and Russians met on Gotland for action. There were trade relations there with Novgorod , the trading center of the East and into the Islamic area.

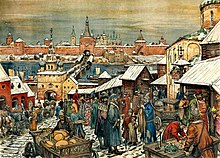

While the Baltic Sea region was still largely underdeveloped, Novgorod was a city-state with great economic strength. The area of Novgorod extended between Livonia and the Grand Duchy of Moscow as well as the entire area belonging to the river system of the Volkhov and Lowater Lands , plus the vast landscapes of the White Sea and the Northern Arctic Sea as far as Siberia . These areas brought Novgorod the wealth of the coveted furs. The flow of goods flowed in the triangle between Novgorod, Gotland and Lübeck: silk and brocade from the Orient, wine from Germany and France, furs from Russia, salt from Lübeck, cod and seal meat from Gotland.

In the meantime, the Holy Roman Empire had established itself as a powerful state in the south of the Baltic Sea region . Based on a strong population growth and scarcity of land, its feudal ruling class began to expand territorially under the decisive leadership of the Duchy of Saxony into the still undeveloped neighboring eastern and northern areas. From the 12th century, the Baltic Sea area was increasingly opened up for German trade as part of the Ostsiedlung .

Until Lübeck was re-established in 1157, Schleswig was a transshipment point for German and non-German Baltic trade. It had taken over a large part of the earlier trade relations from Haithabu on the other bank of the Schlei , the most important trading place of the Vikings, which was destroyed around the middle of the 11th century. In 1095 the Schleswig harbor was expanded and reconstructed, which is evidence of continued maritime trade. It was here that the Jutian - Holstein isthmus was crossed, some of which had to be crossed on land ( Eider-Treene-Schlei-Weg ). As a mediator of trade between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, Schleswig, promoted by the Danish monarchy, flourished in the first half of the 12th century to become the most important trading center in the western part of the Baltic Sea region. It had also linked Rhineland trade and Baltic Sea trade, starting from Schleswig, since the early Viking Age.

It is difficult to grasp the intensity and scope of the Baltic Sea trade carried out independently from and via Schleswig by local and foreign Danish, Frisian , Rhenish and Westphalian merchants. It may be that in the first half and middle of the 12th century it had a predominantly passive character and mainly limited itself to the exchange of goods with the Scandinavians, especially Gotlanders, but also Western Slavs , traders from the Baltic States and Russians in the trading town itself. In addition, other places of trade existed in the south-western part of the Baltic Sea region at the same time, such as the abotritical old Lübeck.

Age of Hanseatic Commerce: 1150–1550

Rise of the Hanseatic League in the Baltic Sea region (1150–1250)

Around the year 1000, Scandinavian merchants began to reorient themselves from the blocked east and southeast to the west. The level of civilization there had risen significantly overall and there was an additional need for food, raw materials and luxury goods, which made it necessary to include the Baltic Sea region in the Western and Central European trade network. German merchants (Saxon, Rhenish and Westphalian) increasingly penetrated the Baltic Sea trade, giving it a new direction and new forms of organization. Until then, the German cultural area was cut off from the Baltic Sea and lay to the west of it, separated by Elbe Slavic tribal federations, which had initially put a stop to the advance of the Germans with the great Slav uprising , but whose cultural peak was long ago.

Lübeck, the old capital of the Abodrites , an Elbe Slavic tribal association, was strategically located on the Baltic Sea and offered excellent conditions for developing into an important and subsequently the leading long-distance trading center in the Baltic region. Lübeck, however, relied not only on the economy and the people of a developed hinterland, but also on a merchant class experienced in Baltic Sea trade, some of which had probably moved from Schleswig and Alt-Lübeck to the up-and-coming town between Wakenitz and Trave . In addition, many merchants from Westphalia immigrated to Lübeck, who had a good trading network in the south for the sale of products.

With the re-establishment of Lübeck in 1159 Heinrich the Lion succeeded in 1161 with the Artlenburger privilege to bring about an understanding between Gotlanders and Lübeck long-distance traders. Both groups now formed a joint trade association, the Gotland Cooperative , an early form of the Hanseatic League, whose members were long-distance traders.

The German merchants did not build their own new trade routes, but instead pushed into the existing ones of the Gotlanders, Flemings and others. However, through their number and their own share in the trade, they increased its intensity and further intensified the relationships. Gotland remained the real center of this cooperative, and over time numerous German merchants settled here. An influential German community emerged in Visby, whose political representation together with the Gotland long-distance traders provided the city council . They became so successful that they were able to oust most of their competitors. It was not yet enough for a monopoly; but in some regions they were already getting close.

The Hanseatic League acted like a guild that demanded strict internal solidarity and could act with economic recklessness towards non-members. Because of the general uncertainty, traders formed trade caravans on land and convoys on water for their own protection. At first it was only a matter of jointly securing the herring transport from the then Danish Skåne to the north German mainland. The herring trade was carried out by the Skåne drivers. Herring was the most important fast food for believers with 140 days of fasting a year and guaranteed continuous sales. In autumn every year the inhabitants of Skåne and the Danish islands went fishing for herring and salted them for the winter. The people of Lübeck could buy salt and herring there, but also sell other products such as cloth or metal goods. More and more merchants from the North Sea area came to the sound to trade with merchants from the Baltic Sea. At the end of the 12th century, the Scanian masses developed from this . For centuries they became the most important place in the east-west trade of Northern Europe. The acceptance of the surrounding road , but also the in the first half of the 13th century newly formed land transit route from Hamburg and Luebeck up to the fairs Scania presented the ancient trade route from Novgorod about Schleswig to the West in question. A unique trading system developed at the Skåne fairs, especially in Skanör med Falsterbo , Malmö , Landskrona and in Dragør on the island of Amager near Copenhagen. Danish, Dutch and German cities acquired their own areas in these places, so-called Witten . At the time of the fair, they could trade there and salt herrings without hindrance. The Witten formed self-contained quasi-cities. At the time of the Skåne fairs, fishing was just as international as trade. In addition to the local Danish fishermen, hundreds of German and Dutch fishermen came to the sound at the time of the fair. A French traveler in the 14th century estimated a five-digit number of boats.

The trading place Visby was initially a key to trade with the East for the Hanseatic League. The German long-distance traders from Lübeck ran together from Lübeck to Gotland and joined the Gotland trade trips to Novgorod in Hansen (meaning for convoy in the 12th century ). The high-sided 200-tonne cogs used by the Germans proved to be superior to the Scandinavian type of boats that had been common in the North and Baltic Seas with mostly only 20 to 30 tons of payload (see Viking shipbuilding ). There they initially found accommodation as guests in the Gotland branch, the Gotenhof , until a few years later they began building their own branch, the Peterhof . The first trade agreement between the German and Gotland merchants dates back to 1190. Prince Jaroslaw concluded this contract with the Germans and Gotlanders after clashes between Novgorod merchants and the Gotland cooperative . The treaty assured the German and Gotland merchants protection of their person and their goods, on condition of reciprocity for the Russian merchants.

Until then, it was common in Europe for merchants to stick to the individual town organization and not form corporations among themselves. The Hanseatic merchants overcame this single-city form of trade organization and thus created an increasingly branching inter-city network.

From then on, the Hanseatic merchants no longer sailed only to Gotland and then to Novgorod, but tried to penetrate into the interior of Russia via all sea trading centers and estuaries. The Low German merchants sought connection to Constantinople , which they sought to reach via the upper reaches of the Daugava near Vitebsk and from there via a short land route to Smolensk on the Dnieper , the waterway to Kiev , which has been busy since the Viking Age . They eventually expanded their trade to include the rest of Scandinavia in addition to Scania and Gotland.

The previously common voyage communities came to an end in the later 13th century due to the increasing pacification of the sea routes. The efforts of Lübeck, but also of Hamburg, had contributed to this, which had concluded inter-city agreements first in the west and later in the east of the Baltic Sea region and thus made individual trade possible. From then on, this was organized centrally in fixed office communities. The early Hanseatic trading system condensed more and more and eventually formed a coherent production and trading area.

The relationship with Denmark, which repeatedly turned into wars, remained important for the Hanseatic League. Since 1200, a lasting pacification of pirates by the Danish King Waldemar II began ( Pax Valdemariana ). He was also the city lord of Lübeck from 1201 to 1225. In the battle of Bornhöved in 1227, Waldemar II was defeated by the north German princes and by Lübeck, which at that time was already the largest and most active city in Northern Europe. Lübeck thereby secured the imperial freedom from the emperor with the Lübeck Imperial Freedom Letter . Then the Danish supremacy in the Baltic Sea area collapsed. This was the beginning of the rise of German Baltic trade under the Hanseatic League.

In Lübeck, new methods of bookkeeping , credit business and commission trading were introduced. The city became the leading transshipment point in the Baltic Sea and emigration port for the Baltic States. At that time, the port throughput was greater than that of Hamburg; for 1368, 423 ships came in and 871 left the port. These carried 250,000 tons of cargo.

Cooperation between the Hanseatic League and the Teutonic Order (1190–1410)

German trade in the Baltic Sea in the 13th century profited greatly from the fact that after the death of Frederick I and the end of the Third Crusade , the crusade movement in Europe strengthened again and from now on turned to the pagan countries in the Baltic Sea region. The Catholic Church tried in the Wendenkreuzzug at the end of the 12th century to evangelize the area east of the Elbe into the Baltic States .

There has been a close relationship with the Teutonic Order since the beginning of the Hanseatic League. In 1190 merchants from Bremen and Lübeck traveled to the Holy Land and took part in the siege of Acre . They founded a field hospital there, which was soon run by a fraternity, which was converted into the Teutonic Order in 1198. The ties to northern Germany were also retained in the following. The order soon carried out tasks of securing the borders of Latin Christianity. Since 1225 he was also active in Prussia . In 1237, after bloody battles, the land of the Order came into being, which expanded into Latvia. This expansion process was accompanied by the establishment of cities and settlement. This was followed by becoming a city of old Slavic trading points on the southern Baltic coast and utter establishment of new cities such as 1201 Riga, Rostock 1218, Wismar in 1228, Stralsund 1234, Stettin 1237, Danzig in 1238 and Greifswald in 1250 and the town charter Konigsberg 1255. The settlement has also increased from inland until finally the entire hinterland of Mecklenburg up to the Memel became the area of production for goods of the Hanseatic trade. Long-distance merchants brought capital into cities that promise legal security and also accept luxury goods . The long-distance merchants in the new cities of the Baltic Sea region transported their goods themselves to the main western sales areas .

A total of 600,000 people from the west settled in the colonized areas. The city constitutions of Lübeck and Magdeburg were adopted everywhere. Lübeck and Magdeburg law was decisive in the eastern Baltic region. The eastern Baltic Sea region received a strong civilization boost and technology transfer since 1150 . German colonists and Slavs merged with each other in the following generations. With the establishment of Riga by the German Order under the patronage of the then Bremen Canon Albert in the summer of 1201, a second German long-distance trading port was established in the Baltic Sea region, also thanks to financial aid from Lübeck. Lübeck's interest in a strong Riga was obvious: Riga served the Lübeck traders as a direct trading partner, but also as a trading base that halved the distance to Novgorod and made the land route to the Novgorod Republic affordable. The German expansion phase lasted about 100 years, until 1240. With the beginning of the trade exchange of the Universitas (Hanseatic form of organization) of the German merchants heading for Gotland, especially with Novgorod and Polotsk , there were commercial establishments on the coasts, mostly connected with the establishment of merchant churches .

The Teutonic Order State reached its peak of power between 1350 and 1400 and had around one million inhabitants. With Danzig and Königsberg and four other places it had important trading centers for the Hanseatic League. The knights of the order mainly carried out wholesale activities with wood, amber and grain. The Battle of Grunwald in 1410 ushered in the end of this state.

Russia trade during Mongol rule (1240-1380)

As a result of the Mongol invasion of the Rus , Novgorod, the Russian trading center on the Baltic Sea , paid tribute to the Mongol invaders , but otherwise maintained its internal autonomy and was not destroyed by the Mongols. A dark time came for the Russian cultural area, but the civilizational cuts also meant that Eastern Europe remained a bridge country for international trade under the rule of the Golden Horde. The Novgorodians were dependent on the Baltic Sea trade, which was now dominated by the Hanseatic League, because Russia had to (and could) earn the silver in the Baltic Sea trade, which was to be delivered as a tribute to Sarai , the capital of the Golden Horde . In addition to silver, Novgorod imported copper , tin , lead , iron and other metal products, textiles, dyes, amber , glass, beer and wine from its Baltic trading partners . To pay for these imports, Novgorod merchants exported honey, wax, sable and luxury hides , which they had previously acquired from Finnish tribes resident up to the Ob . Novgorod concluded trade agreements with Vladimir-Suzdal , the leading trading center in Central Russia . Novgorod tried to maintain its primacy in Russian trade over the other Russian capitals and to control the flow of goods with central Russia. It was not easy for the city to maintain this mediator position between Europe and Russia . Since the time of Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky , the subducal principalities of Vladimir and Suzdal tried to operate an independent trade, and in Novgorod itself a political party tried to bring the Novgorod trade under the control of the central Russian principalities.

The flow of goods went from the Baltic Sea via Novgorod on via Suzdal to Sarai. There, goods were then partially included in the trade flow of the Silk Road to China. Russian-Novgorodian traders returned from Sarai to Novgorod with glazed ceramics , glassware, silk and other Chinese goods.

The establishment of German rule in the Baltic States and the founding of cities at the beginning of the 13th century created the prerequisites for a further eastward trade route. Land and waterways leading eastwards emerged, developed into trade routes and were secured. German and Livonian merchants from Reval, Dorpat and Riga appeared mainly in Pskow because of the geographical proximity . In contrast to neighboring Novgorod, a Hanseatic office was not established in Pskow, as the proximity to the Livonian cities made it unnecessary for the Hanseatic merchants to stay longer. In addition to Novgorod, Pskov also resisted the destruction by the Tatars . The city was also an important Russian foreign trade center, making it especially its location at the confluence of Pskowa and Velikaya owed. Although Pskov lagged behind Novgorod in terms of trade volume, the city was one of the most important Russian trading bases and rose to become the most important center of Russian trade with the west after the Peterhof in Novgorod was closed in 1494 and Novgorod was destroyed by the aggressively expanding Grand Duchy of Moscow. After Moscow incorporated the Pskov Republic in 1510, trade shifted more to the Livonian cities. Nevertheless, in the 16th century, German trading branches were set up in Pskow. In 1603 Lübeck merchants received a trading privilege from the Russian Tsar Boris Godunow , which allowed them to have their own trading yards in Novgorod and Pskov.

Just like to Pskow, Livonia also brought you to other East Slavic trading cities: to Polatsk and Vitebsk , both on the Daugava , and from the Daugava through its tributary Kasplja and over a stretch of land to Smolensk on the Dnieper . The cities of Polatsk, Vitebsk and Smolensk became further targets of the Hanseatic merchants in the Dunes region. In 1229 they concluded a trade agreement with the Prince of Smolensk . The three cities forced the German merchants to stay within their walls via the stacking right. The Hanseatic merchants subsequently set up trading shops . If Smolensk was a city with a large Russian population, Polatsk and Vitebsk were Belarusian cities. However, the German branch in Smolensk did not experience an upswing comparable to that of Novgorod.

The heyday of the Hanseatic League (1350-1430)

Visby initially remained the hub in the Baltic Sea trade, but increasingly fell behind compared to Lübeck. Visby's decline accelerated after 1300. From then on it was dependent on the arbitrariness of foreign powers, was conquered and occupied, plundered by pirates, destroyed and burned down by its old partners. In the Battle of Visby in 1361, the Danish King Waldemar Atterdag destroyed the Gotland peasant army off Visby. He then conquered and plundered the island. Visby and with it the whole of Gotland lost their previous supremacy in the Baltic Sea trade. The headquarters of the Hanseatic League were finally moved from Visby to Lübeck.

The Peace of Stralsund in 1370, which ended the Second Waldemark War victoriously for the Hanseatic League, marked the height of the power of the Hanseatic League of Cities in the Baltic Sea region. Its heyday followed. The favorable political situation for the Hanseatic League was converted into tangible commercial advantages and monopoly positions. The Hanseatic League now had a trade monopoly and had permanent representations and offices in important Baltic ports. Significant trade relations between the Hansa and the Peterhof also existed with the Novgorod Republic. The north-maritime east- west trade was also dominated by the Hanseatic League and stretched from Novgorod in the east to Bruges and London in the west. She also had a great cultural influence on the development of many regions in which she did trade. This is how German architecture, painting and sculpture spread. But the dissemination of technical knowledge and the written language are also closely linked to the Hanseatic League.

The Hanseatic League had also continued to grow geographically. Lübeck entered into a union with Hamburg as early as 1241 . Both cities dominated the Elbe and the German Bight . The union had expanded in 1259 after Wismar and Rostock joined. In 1358 the Hanseatic League finally comprised 200 cities. This association of cities had become by far the most powerful in Europe. The Hanseatic League continued to develop into a combat alliance which, if necessary, did not shy away from war with military means and had an army and a federal fleet. In trade wars the were in the form Verhansung goods boycotts of a port or country pronounced. Resolutions on this were passed at the Hanseatic Days. Hanseatic policy included the following recurring patterns of action to safeguard and secure common interests in long-distance trade and shipping:

- Guarantee of trade advantages through:

- Stacking right for own goods in other places

- Stacking obligation for foreign merchants in the Hanseatic ports

- Establishment of joint branches

- Appointment of arbitration tribunals in commercial matters

- Views of the Hanseatic town squares

| city | Population 1400 | Population 1600 |

|---|---|---|

| Veliky Novgorod | 25,000-30,000 | <5,000 |

| Danzig | 20,000 | 50,000 |

| Lübeck | 17,200 | 30,000 |

| Rostock | 13,935 | 14,800 |

| Stralsund | 13,000 | 12,500 |

| Thorn | 12,000 | 10,000-12,000 |

| Elblag | 10,000 | 15,000 |

| Koenigsberg | 10,000 | |

| Szczecin | 9,000 | <10,000 |

| Wismar | 8,000 | |

| Riga | 8,000 | |

| Greifswald | 7,000 | |

| Copenhagen | 6,000 | 20,000 |

| Reval | 5,000-8,000 | |

| Stockholm | 5,000-6,500 | 10,000 |

The most important Baltic trading metropolises in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period included Gdansk , Königsberg , Riga , Stockholm , Rostock , Lübeck , Greifswald , Stettin , Copenhagen , Reval , Novgorod , and later from the 18th century Saint Petersburg . Hinterland cities with river connections also belonged to the economic system of the Baltic Sea trade. The Oder and Vistula were and are important feeder waterways .

The Lübeck trading center was the most important trading hub for North and Baltic Sea trade in the Middle Ages. The following regional trade centers developed specialized trade product focuses:

- Visby: pitch and tar,

- Reval: wax and flax ,

- Rostock: malt ,

- Danzig: barley and wheat,

- Szczecin: fish.

The beer trade in particular was of great importance to the Hanseatic League. In 1368, 1,673 tons of beer were shipped from Lübeck to Skåne, 104 tons to Gotland and 24 tons to Kahrmar. In relation to the herring trade, the total number of herring barrels imported into the Hanseatic cities at the end of the 14th century is estimated at 150,000 barrels a year, half of which went to Lübeck.

The fur trade was considered the basis of the Hanseatic prosperity, but was subject to sales and price risks. Sheepskins went to the Baltic Sea region from England and Scotland . Eastern European wax from wild bees was indispensable for liturgy purposes and found steady sales with average profit rates of 10 to 15 percent. The Hansen had a monopoly of trade in furs and wax since the 13th century and were able to maintain it for wax the longest. Salt was almost completely absent in the Baltic Sea region, as the low salt content of the Baltic Sea did not allow salt to be extracted from seawater and rock salt could only be extracted in small quantities in the Kolberg salt pans . However, the need for salt for preservation purposes was very great. Until the middle of the 14th century, salt was almost exclusively supplied to Eastern Europe by Lübeck. Lüneburg salt was Lübeck's main export product and established Lübeck's urban wealth. Rye, barley and wheat have been transported from the areas of the central Elbe to the Netherlands since the 13th century. The steadily increasing demand for grain led to Prussia and Poland beginning to export grain to the West on a large scale from the 15th century.

The Hanseatic League had success with its economic freezes and in the wars; it was able to hold its own partly brilliantly and for a long time. But this could not stop the course of time. A major weakness of the Hanseatic League was that it acted as a middleman for goods, the manufacture of which was beyond its political control. Everywhere the Hanseatic League arose from this competition on the fringes of the Hanseatic region, such as, for example, southern German businessmen who gained a foothold in Stettin and Danzig. In the following years Dutch, English merchant adventurers and southern Germans with Nuremberg at the top became dangerous competitors of the Hanseatic League and challenged the Hanseatic supremacy in trade.

Establishment of Prussian trade in the 15th century

In the late Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Renaissance Europe was unevenly developed. West and South Europe were politically, economically, technically and culturally on a comparatively high level. At the same time, they were poor in raw materials. The population growth of the 16th century made it difficult to supply the people there because there was not enough high-quality arable land available. Northern and Eastern Europe, on the other hand, were underdeveloped in almost every respect, but had raw materials and large arable and pasture areas. The balance between the two economic zones occurred in the late Middle Ages mainly in the south-east direction. Trade in the Baltic Sea region, that is, with raw materials, fish and grain, continued to be dominated by the Hanseatic League.

With the German expansion to the east until 1400, the Baltic Sea region was mainly settled south of the south coast. Initially, a settlement focus developed on the Bay of Lübeck up to the Oder , from which a total of six important Baltic ports grew in the following period. Somewhat delayed, a second important settlement area arose east of the mouth of the Vistula up to the Memel , which was also urbanized by German settlers. This second largest urban area in the Baltic Sea region developed four important trading centers. In addition, there was only the old Russian trading center of Veliky Novgorod in the Baltic Sea region around 1400 , although it remained a monocenter surrounded by vast, almost human-free areas. The network of settlements in the other smaller centers such as Riga and Reval in the Baltic States remained just as wide-meshed and loose as on the western Baltic coast of Copenhagen or Stockholm, which in turn lagged significantly behind the southern Baltic metropolises in terms of size.

Around 1400, due to the lack of people in the north of the Baltic Sea, the Baltic Sea trade was primarily trade between the two separate southern Baltic Sea areas of Mecklenburg with its immediate vicinity and West and East Prussia . The actual Prussian trade increasingly tried to establish itself and to develop its own focus in international events. Their geographic location encouraged their interest in the Swedish-Finnish market. So there was agreement between the Prussian traders and the Swedes. From then on, a large part of the Swedish iron exports went to Gdansk, which in turn were transported across the Sound to the west - past the Lübeck intermediate trade, i.e. without unloading and stacking the goods in Lübeck. This damaged the older trading centers from Lübeck to Stettin.

The crisis in long-distance trade spared Danzig and Königsberg, while Kulm , Thorn and Elbing suffered setbacks. Gdansk gained in attraction and attracted settlers from other countries in the 15th century. Access to the Lithuanian hinterland had a positive effect on the economic development of the cities of Königsberg and Kneiphof on the Pregel . The trading activities of the Gdansk merchants in the 15th century were characterized by great flexibility and the striving to gain influence on the new sales areas and access to new raw material areas. Lübeck and Danzig represented completely different political and economic interests in the 15th century. The political grouping of the Hanseatic League began to dissolve the more the cities in Prussia broke away from the guardianship of Lübeck.

Effects of the early bourgeois revolutions and refeudalization

At the end of the 14th century, a phase of long-lasting economic depression began in the entire Baltic Sea region, which affected most of the neighboring cities. This development was part of the long-term European economic development in which the Baltic Sea region had been involved since the 13th century. The renewed economic boom in the Baltic Sea region started after 1525 after population growth, increasing urbanization and commercial growth in Western Europe had generated increasing demand, especially in the Netherlands. A pan-European division of labor was created to satisfy the various goods needs. The Baltic Sea mainly supplied grain to the western markets. This course of development stood at the beginning of a subsequent process of refeudalization, particularly in the southern and eastern Baltic Sea region, which lasted until the peasants' liberation in the 19th century.

The aristocratic landowners ( Junkers ) east of the Elbe , including Poland, Lithuania, the Baltic States and further east, wanted to benefit from the increased grain prices and saw to it that production costs were reduced by increasing their basic rights in cooperation with the rulers of the once free peasantry withdrawn until they had sunk almost entirely to serfs without rights . Even within the nobility, there were ruinous processes of concentration in agriculture. The control of grain production was concentrated on a few leading noble families per province. Their production went via inland shipping to the seaside cities (Hamburg, Stettin, Danzig, Königsberg, Riga, Reval, Narva), where they were then sold.

While in Western Europe in the regions in which the early bourgeois revolutions were successful, early capitalism was finally able to prevail and the productive forces developed, in the peripheral eastern areas of the Baltic Sea, in which the bourgeois class could not prevail in the early bourgeois revolutions there ( German peasant war , Hussite movement ) weakened by the nobility including the sovereigns in cooperation and ultimately marginalized at the expense of the stagnation of the social differentiation that has already been initiated . This led to a tendency to paralyze the economy, urban and state development. This was particularly evident in Poland-Lithuania, whose aristocratic class , which supported the state, degenerated more and more and had a harmful effect on the community. The dividing line between these two opposing lines of development is drawn on the Elbe. Ostelbien stood for Gutsherrschaft west and lack of freedom, the area of which for civil freedom and fundamental rights.

Rise of Dutch trade (1350-1400)

But the Hanseatic monopoly has been increasingly successfully undermined by the emerging trading nation of Holland and Zealand since the late Middle Ages . This region of Europe was not affected by the general demographic and economic crises of the continent in the 14th century. There, in the intermediate area between sea and land, the landscape-related borders led to concentration processes and the establishment of labor-intensive processing industries that were primarily oriented towards export. As a result, there was a lack of grain products to supply their own population. This good was in turn in large surpluses in the southern Baltic region (center of Danzig and Stettin). The grain supply through foreign markets, especially in the Baltic Sea, became an essential part of the Dutch economic model.

Because the continuous import of grain had to be paid for with an offer of goods, the Dutch offered their own products in exchange for grain. So they gradually gained market share for beer, cloth and North Sea herring. These products were imitations or variants of the Flemish and Hanseatic branded goods, but cheaper than their models. In addition, it was mainly ships and freight services that gave the Dutch access to the Baltic Sea region. There was little shipping space there. However, the Dutch had established a strong shipbuilding industry and had large fishing fleets with which they caught the abundant herring stocks in the North Atlantic north of Scotland. As the export of grain from the Baltic Sea to the industrial regions of the west increased, so did the demand for Dutch shipping space. This created an increasing competitive situation with the Hanseatic cities, including Wismar , Lübeck, Rostock, Greifswald and Stralsund . They saw their positions in intermediate trade and in goods transport on the east-west route threatened. However, the Hanseatic cities did not succeed in restricting Dutch access to the Baltic Sea, neither by peaceful nor by military means. The Prussian cities of Königsberg, Danzig, Thorn and Elbing , on the other hand, were heavily reliant on Dutch ship transports. Between 1490 and 1492, 562 ships entered Gdansk and 720 ships annually. Compared to 1368 (400 incoming and 634 outgoing ships), this meant an increase in trade in goods of around 24 percent.

The Dutch trade network continued to grow, especially through the Brabant trade fairs in Antwerp and Bergen op Zoom , which enabled Dutch merchants to expand their range of trade products more and more. The imports of tar and pitch from the eastern Baltic were of fundamental importance for the shipbuilding industry in Holland.

The core elements of Dutch trade were already established before 1368 - when Holland, on the side of the Hanseatic League, waged war against Denmark and thereby expanded its position in Skåne . The participation of the Dutch in the war against Denmark from 1367-70 led to the acquisition of fortresses on the coast of Skåne. Here they probably learned the technique of gutting the herring, curing it and storing it in wooden barrels of a thousand each. The Hanseatic League viewed this activity as a threat to its monopoly of the Skåne fairs and in 1384 forbade the Dutch to catch herring off the coast of Skåne. However, in 1399 Zeeland still imported herring to Great Yarmouth . The Skåne Masses were used by the Dutch to exchange cloth for rye with the Prussian monastic state and Livonia . As early as 1384 the Hanseatic League took measures against the importation of the Dutch cloth and the Dutch herring into the Baltic Sea. In 1377 and 1385 it was mentioned that the Dutch and Zealanders regularly imported into the Hanseatic cities, and in 1401 and 1402 there was talk of the import of Leiden cloths to Russia and Gdansk. English cloth was also transported by an Amsterdam shipper. In 1413 a Dutch trader was mentioned in Reval who had exported grain despite the trade ban. In 1416 there were complaints at the Hanseatic Congress against Dutch grain purchases. A year later, a German merchant in Bruges lodged a complaint against direct trade between Holland and Livonia and wanted it to be banned. In Livonia, the Dutch came into direct contact with the producers. Despite protectionist measures, more and more Dutch ships sailed the Baltic Sea and penetrated it expansionistically and aggressively.

In addition to herring and cloth, the Dutch also exported beer to the Baltic Sea in return for importing grain. However, it was often difficult to find the same amount of freight . The proportion of Dutch ships sailing east through the sound with ballast was a third. Salt was another trade alternative . There were salt pans along the Meuse , in the Dordrecht area , and another 150 in Zealand. Salt from the Atlantic coasts, from Bourgneuf to Setubal , became cheaper and cheaper and could compete with Lüneburg salt . In Reval, a load of rye cost about as much as two loads of salt in normal years and as much as four loads of salt when there is a shortage of grain. Since the Dutch continued to concentrate on the fast and inexpensive transport of grain, wood, herrings and salt, they increasingly successfully ousted the Hanseatic League from western trade. The herring from the North Sea, the salt of the Bay of Biscay , and wine from France in return for Swedish iron and copper reached the Baltic Sea region ; but primarily grain, wood and forest goods were exchanged.

Appearance of English merchants in the Baltic Sea, introduction of the sound tariff, Vitalienbrüder (1370–1430)

In addition to the Dutch, English merchants were increasingly pushing their way into the Baltic Sea as so-called suburban travelers , but always lagging behind the Dutch . English merchants came to the Teutonic Order in a significant number from the last third of the 14th century and from then on formed their own trading colonies in Danzig, Königsberg, Elbing and Memel . The result was trade-political entanglements and disputes between the Hanseatic League and England, the Order and England, Danzig and England and above all between Danzig and the English merchants trading in the city - disputes that went on almost without interruption for a period of 150 and spanned more years. The English tried to get permission to settle in Gdansk and to form a corporate group, to participate in business, to obtain citizenship and the right to wholesale and retail, while Gdansk struggled to completely exclude all foreigners from buying and selling goods independently in the city. Both sides used all possible means, including reprisals against the Hanseatic merchants in London and the removal of Hanseatic goods and ships by raids at sea. The result was a relationship that was almost never completely peaceful and that can be characterized as something between struggle and tolerance. Trade wars, e.g. B. from 1379 to 1388, 1392 to 1409, 1430 to 1437, 1447 to 1474, and trade agreements, such as those of Marienburg 1388 and 1405, of London 1403, 1409 and 1437 or of Utrecht 1451 and 1474, replaced one another. However, none of this could force the English trade guests to give up their branch in Danzig. Around 1422, 55 English merchants lived in the city, some with their families. There they maintained a trading post , whose members in a confirmed by the British government corporation headed by an older man supported each other in their commercial enterprises.

Conversely, since the 1290s, the Teutonic Order members engaged in active trading in England. The aspiring English trading bourgeoisie tried more and more to break the prerogatives of the Hanseatic League in Baltic Sea trade. This led to the Hanso-English War from 1469 to 1474. The abrupt decline in the important English wool trade by the Hanseatic merchants caused great economic damage and was one of the main reasons for the sudden end of the war.

The introduction of the sound tariff in 1429 (only abolished in 1857) by Denmark for non-Danish passing ships led to war with the Hanseatic League . The cannons at Kronborg Castle at the narrowest point of the Oresund enforced the levy. The Dutch Sundfahrt was in 1547 1105 and in 1557 1270 ship passages. It is true that the bulk goods of grain and wood, as well as the salt of the West, remained dependent on the shipping route across the Sound; but the Stecknitz Canal, completed in 1398, and the most important land route of the Hanseatic League, the overland route from Lübeck via Oldesloe to Hamburg, the North Sea-Baltic Sea Road , offered alternatives.

Around 1400 the Vitalienbrüder, with Klaus Störtebeker as one of the leaders, disrupted trade in the Baltic Sea. They carried out pirate trips for the Swedes and supplied Stockholm, which had been besieged for five years, with goods as a blockade breaker. They were a mercenary association specializing in naval warfare that had degenerated into a gang of pirates. They were driven by a fleet of the Teutonic Order from their base in Gotland and then by the Hanseatic League from the rest of the Baltic Sea into the North Sea.

Descent of the Hanseatic League (1430–1550)

The Hanseatic League was only able to react to the expansionist efforts of the Dutch and English and permanently lost its momentum (attraction). Its former flexibility, which characterized the Hanseatic League in the late Middle Ages, was lost and it acted more and more static on changes. In 1423 the Hanseatic cities tried to ban Dutch and English goods from the Baltic Sea. Hanseatic boatmen and men were forbidden to bring Dutch or English goods to Prussia in 1428; the Dutch themselves were also not allowed to transport Prussian goods. The Hansen was prohibited from building ships and selling them to Dutch, Flemish and Lombards in 1434 and 1435. However, the many conflicts surrounding arrests showed a strong Dutch presence and the protectionist measures were unsuccessful. In 1434, it was forbidden in Livonia to bring the goods further than to the quay and to use interpreters or brokers to help. However, these countermeasures had no effect because the Hanseatic League could no longer establish a consensus within its association . The commercial interests of its own members diverged too widely. The freedom of movement between the members when attempting compensation decreased, as many forces had been at work in the Baltic Sea region since the 15th century and permanent changes were in progress.

The Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and the city of Danzig supported their Dutch trading partners, who were also prepared to pay a shilling tax on imports and two pfennigs on exports. In 1436 the Duke of Pomerania broke the driving ban in the direction of Holland. In 1475/76, a quarter of Gdansk shipping traffic was already done by Dutch ships, the rest mainly by the Hanseatic League. However, the Dutch steadily increased their shares.

The Hanseatic League was no longer able to achieve the same rate of isolation of the Baltic Sea as in earlier times. As a result of this weakening, the integration of the countries bordering the Baltic Sea into world trade increased. The cities of the Teutonic Order were interested in a direct sea connection with Western Europe and forced the sea route through the sound to the detriment of Lübeck's intermediate trade market and Travestapels. The Prussian maritime trade , focused on Gdansk, led to Flanders and England. In the 15th century relations were established with Holland, Scotland, Lisbon and the Bay of Bourgneuf ( Baienfahrt ). Thorner merchants advanced via Krakow to Lemberg and met there until 1400 with Genoese and Venetian merchants who had got there via their branches on the Black Sea . For the shipping route Bruges – Lübeck – Reval, the land connection of the Via Regia from Frankfurt am Main - Nuremberg - Leipzig - Wroclaw - Posen, south of the Hanseatic region, has been dangerous since the 15th century . It kept southern German, Italian, Central European and Russian goods from entering the sea.

The Hanseatic League was increasingly weakened by the strengthening of the sovereignty of the princes, who robbed many cities of their freedom of action. In addition, there was the growing technological deficit compared to the Dutch and English, who had better and cheaper ships. The schools of herring also migrated from the Baltic to the North Sea for reasons unknown to this day. As a result, the Hanseatic League lost one of its most important economic foundations. The Dutch were also able to achieve a technological lead, which ultimately ended the dominance of the Hanseatic League in the Baltic Sea trade.

The Hanseatic League grew weaker and experienced internal disintegration. The emergence of the centralized nation-states of Scandinavia, combined with growing political independence, intensified the crisis in the Hanseatic trading system. The result was that decisive changes in trade took place within the traditional Hanseatic economic area. The countries between which the Hanseatic League had previously mediated became more and more important. Due to these development tendencies, the Hanseatic League was less and less able to maintain the traditional trade monopoly on which its livelihood was based. Rather, these changes contributed to increasingly shaking their position of power in foreign policy. The emerging centralized and national monarchies in Northern and Western Europe were no longer willing to continue to confirm the old privileges with which the Hanseatic merchants had ruled the trade of these states for centuries. The struggle for the sanctioning of privileges determined the content and aim of trade relations with these countries in the second half of the 16th century. The feudal institutions were shaking everywhere. In the Netherlands and England, national markets began to emerge and their own merchants to develop. Their local merchants took the view that privileges for foreign merchants were detrimental to domestic trade. These economic actors were under the protection of the sovereign central authority.

A similar trend emerged in the Scandinavian countries. The isolated Scandinavian hinterland turned into modern European nation-states. There were increasing national contradictions that overlaid trade. The competition between Denmark and Sweden for supremacy in the Baltic Sea, which began around the middle of the 16th century, was from now on the focus of foreign policy in both countries.

There was no such tendency within the Holy Roman Empire. The few attempts by the Habsburg emperor to take sides with the Hanseatic League in international disputes came to nothing.

The Grand Duchy of Moscow under Ivan III. After the centuries-long incursion caused by the Mongol invasion, was able to significantly advance the collection of Russian soil , conquer the Novgorod Republic and close the Peterhof in Novgorod in 1494. This significantly strengthened the southern land trade route from Moscow and Kiev to Leipzig via the Via Regia . In addition, the Teutonic Order, which had always backed the Hanseatic League, fell back to the level of a Polish fief with the Second Peace of Thorn and thus ceased as a regional power.

On September 25, 1604, King James I of England rejected the proposals to restore the privileges of the Hanseatic cities. This meant the end of the Hanseatic privileges in England after more than three centuries. For the Hanseatic League, the loss of the privileges of the rulers and the great people close to them in the kingdoms was fatal. As a result, the foreign rulers deprived the Hanseatic cities of the independence they had previously been granted in commercial matters. They were no longer fully-fledged trading partners. This led to the closure of the office in London and similar events in other places and finally to the silent dissolution of the Hanseatic League.

Age of the Northern Wars for Dominium maris Baltici 1550 - 1720

Struggle for control of trade in the Baltic Sea

The end of the medieval states in the Baltic States, the Livonian Order and the Teutonic Order led to the destabilization of the Northern European power system and aroused the desires of expansionist neighbors. Above all, competing economic and military interests ensured an intensification of the military conflicts in the countries bordering the Baltic Sea. While Denmark, Sweden and Poland fought for rule over the Baltic Sea coasts and also justified this dominium maris Baltici with journalism, the Netherlands tried to protect the interests of their merchants and shipping in general. As early as 1493 an Amsterdam warship had rescued a Hamburg ship from the hands of pirates - probably allied with Sweden . Thereupon the strong man of Sweden, Sten Sture , recommended the Amsterdamers that they should compensate him for the lost profit if they were still interested in the Baltic Sea shipping in the future. In the next few years the Dutch concern about the Baltic Sea trade was omnipresent and led to the construction of regional-strategic claims. The Baltic Sea was now seen as essential to the economy of Flanders and Holland . In view of the disputes between Denmark and the Hanseatic city of Lübeck , which claimed a Baltic Sea trade monopoly , access to the Baltic Sea for Dutch merchants seemed at risk.

Sweden in particular was able to assert itself as the most powerful empire in the Baltic Sea in numerous armed conflicts with Denmark, but also with the strengthened Grand Duchy of Moscow and later Tsarist Russia.

Originally, the settlement area of the Russians did not extend to the Baltic Sea. Under Moscow's rulers, Ivan III tried. first in the late 15th century to gain direct access to the Baltic Sea. The submission of Novgorod certainly brought the city into Moscow's hands; the western trade that Novgorod had operated, however, was only indirectly via Lake Ladoga . Further Russian attempts in the Livonian War to gain access to the Baltic Sea in the Baltic States failed. At the latest with the Peace of Stolbowo , which ended the Ingermanland War between Sweden and Russia, Russia was again kept away from the Baltic Sea by Sweden for almost 100 years. In the 17th century, Russia was only able to participate in trade with the West indirectly via Swedish trading ports in the Baltic States. Sweden became a bulk buyer of Russian grain and lowered tariffs to encourage merchanting through the Baltic ports. In addition to the older products of grain, flax and hemp, wood appeared as a new commodity. From the middle of the 17th century, Russian timber exports began via Narva. Of all the Baltic ports, Narva had the greatest success in trade with Russia. Nevertheless, Russian trade had lost its independence; because the trade routes running through Swedish territory were controlled by the Swedish customs and could arbitrarily be blocked at any time, thereby interrupting trade.

Structural change in trade in the Baltic Sea and shift in world trade in the 16th and 17th centuries

Globally, the world economic situation had since the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus changed. The global flow of trade and goods shifted to the North Atlantic and now also included Asia, China, Africa and the Americas. A European economic boom set in on the Atlantic. In contrast, the Baltic ports inevitably lagged behind. From now on, Hamburg and the English ports in particular benefited from global trade flows in the north.

As a result of the competition between the Hanseatic League and the Netherlands, this led to a loss of importance for the entire Baltic Sea region. Lübeck in particular suffered heavily from the losses of the Hanseatic League due to structural change in the Scandinavian-Baltic region. In addition, there was the rapidly growing competition from the Dutch, the British and, finally, the Russians in the Baltic Sea trade. Nevertheless, there is no general decline in the Baltic Sea ports either. Because the commercial revolution of the 16th century not only affected the Atlantic, but also, and earlier, the Baltic Sea. In addition to the traditional supply of the western industrial zones with Baltic grain, it was now about the delivery of the increasingly urgently needed raw materials, especially for shipbuilding (wood, tar, hemp, hides, leather). On this basis, Lübeck was able to expand its trade with Western Europe until the 17th century, as did the Hanseatic cities of Rostock, Wismar, Stralsund, Greifswald and Stettin, all of which were restricted by the princely territorial state that was forming. Refeudalisation began in the East Elbe areas, as a result of which the cities increasingly lost their autonomy from the princes. The Hanseatic inner city of Berlin, for example, has been banned from participating in the Hanseatic Days since the middle of the 15th century. Nevertheless, the ports were able to at least partially offset the losses from the older Hanseatic trade. Stralsund in particular succeeded in making the transition from the medieval system of privileges to the new model of trade relations based on equal rights for partners. In the east, Danzig had developed more and more into a metropolis since the end of the 14th century and in the late 16th and 17th centuries it achieved absolute dominance in Baltic trade. In the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries, Danzig alone handled 75 percent of Polish foreign trade. During this period, Gdańsk's share of grain exports from the Baltic Sea region was more than 60 percent. After 1650, the place had to accept significant losses in trade. By 1700 the port had lost two thirds of the sea trade that Danzig had achieved around 1600. The main cause here was the English grain export, which caused the demand for English grain export to decline.

Disputes between Danzig and Poland were also of great importance. Elbing , which until the 1370s had a dominant position in wholesale shipping among the Prussian cities, pursued its own trade policy. King Stephan Bathory transferred to Elbing the pile previously held by Danzig for all goods to be sent seaward from Poland. Elbing allowed the establishment of the English Eastland Company in 1579 in the competitive situation with Danzig , which declared this city to be its only trading center in Prussia. The contract agreed with the Elbingen council secured her, besides the right of free wholesale trade, a privileged foreign colony with extensive self-administration of her internal affairs and a whole range of other advantages. It was not until 1628 that the Danzig and Prussian land messengers succeeded in persuading the King and Diet of Poland to abolish the English trading partnership in Elbing.

Since then, trade with England and Scotland has been the top priority for this city, and in the late 16th and early 17th centuries more than half of all Elbing's ships sailed for England. Immediately a flourishing English trading post was established in Elbing. The Hanseatic representatives pulled out all the stops in the fight against the English and tried to get the Emperor and the Reichstag to expel the English from the Reich. The emperor approved the vote of the Imperial Court Council , and on August 1, 1597, the mandate that expelled the Merchant Adventurers from the soil of the empire was signed.

The cities of Riga and Narva, some of which were inhabited by Germans, experienced an economic upswing because they primarily exported raw materials for shipbuilding.

Domination of the Dutch in Baltic trade (1550-1700)

The Danish-Hanseatic War from 1509 to 1512 meant that the Hanseatic League had to recognize the rule of the Danish king over the key position in the Baltic Sea, the Öresund, and allow the Dutch to access the Baltic Sea. The Dutch and the Zealanders functioned more and more as the successors of the Hanseatic League and as new important mediators between the Baltic and North Seas.

Due to the unsuccessful intervention of Lübeck in the count feud from 1534 to 1536, the city finally lost its political and economic backing in the Baltic Sea region and the position of a Nordic power. The further disintegration of the Teutonic Order in the following decades left a power vacuum and led to political instability and wars. The Kalmar Union also ended. The downfall of the medieval powers came about as a result of great upheavals in the entire European system.

At the Diet of Speyer in 1544, peace came to Speyer . In it, the Danish Crown Charles V certified the freedom of passage through the Sound for his Dutch subjects. This legally guaranteed access to the Baltic Sea for the Dutch. They now penetrated the Danish economic area, which had previously been a cornerstone of the Hanseatic supremacy. Since the second half of the 16th century, only the Wendish group of cities of the Hanseatic League with the core of the Lübeck quarter of the Hanseatic League remained. Only this smaller group continued to pursue a uniform trade policy. Absolute supremacy in the Baltic Sea trade had passed to the Netherlands. Compared to the Dutch trade volume, Anglo-Scottish trade made up a relatively small proportion of the Baltic Sea trade. The Baltic Sea trade played only a subordinate role for the English trade overall. The aim of the English merchants was limited to taking English cloth exports out of the hands of the Hanseatic League in order to make the trade profits themselves. Denmark and Norway gradually increased their own share in the Baltic Sea trade at that time. The direct connections between Sweden and the Netherlands remained low during the Hanseatic period, as Sweden did not deliver the goods desired by the Dutch on a large scale. Until the time of Gustav II Adolf, the main flows of Swedish foreign trade went from the Swedish trading center Stockholm to Lübeck and Danzig. Therefore, they did not pass the sound, but ran within the Baltic Sea.

| Period | Netherlands | Lübeck quarter | England | Scotland | Denmark | Norway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1560-1564 | 9,043 | 2,258 | 331 | 336 | 181 | 88 |

| 1565-1569 | 12,395 | 1,518 | 567 | 332 | 450 | 57 |

| 1575-1579 | 10,307 | 3,542 | 1,036 | 707 | 1,268 | 164 |

| 1580-1584 | 13,133 | 4.019 | 790 | 336 | 1,922 | 143 |

| 1585-1589 | 12,735 | 4,946 | 1,274 | 572 | 2,067 | 327 |

| 1590-1594 | 15,769 | 4,371 | 734 | 503 | 1,577 | 289 |

| 1595-1599 | 16,980 | 3,974 | 1,063 | 827 | 1,945 | 386 |

The entire Hanseatic merchant fleet numbered 1,000 ships at the end of the 15th century and their carrying capacity was 60,000 gross registered tons . At the end of the 16th century the total tonnage of the Hanseatic League had already increased to 110,000 tons. 100 years later the fleet had shrunk. The Dutch merchant fleet at the end of the 15th century was just as large as the Hanseatic fleet with around 60,000 tons. Their total tonnage increased faster than the Hanseatic one; at the end of the 16th century it was already 232,000 tons and was therefore more than twice the size of the Hanseatic fleet. In 1670 the Dutch fleet numbered 3,510 ships with a load capacity of 600,000 tons. Of these 3510 ships, 735 were still trading in the Baltic Sea. These had a load capacity of 200,000 tons; so around a third of the fleet (in terms of tonnage) mainly sailed the Baltic Sea.

In the 17th century, grain also declined overall in the share of the Baltic Sea trade due to the continuing decline in prices.

In line with European developments, the Electorate of Brandenburg ( Brandenburg-African Company ) and Kurland ( Kurländische Handelskompagnie ) tried to participate in transatlantic trade by setting up their own trading companies . Aligned with trade outside the Baltic Sea, like the Swedish East India Company , they were unable to develop any noteworthy effect on internal Baltic Sea trade. After 1700, Brandenburg-Prussia focused more on inland development and relied on being able to handle the necessary seaborne import goods via the Hanseatic cities.

In the 16th century, Dutch ship designers developed the flute, a new type of ship. Such a ship was four to six times as long and wide as previous ship types in the Baltic Sea and could therefore carry more cargo than all other known models. In addition, it required far fewer crew members than other ships. This enabled the Dutch to leave all of their competition in the Baltic region behind. The Baltic Sea trade, which formed the backbone of the Dutch economic miracle, was called "moedercommercie" ("mother of all commerce") by contemporaries. In the 1580s about half of Gdańsk's imports and exports were handled by Dutch ships. The proportion later rose even further to 60 to 70 percent.

In the Dutch sources of this time, the sphere of interest of Dutch trade is defined as Oostland . The expiry of the armistice with Spain in 1621 brought a serious crisis for the Dutch Baltic trade in grain. Wallenstein issued an export ban in November 1621 in order to destroy the Dutch Baltic Sea trade. The Hanseatic cities did not follow suit. The goods from India , which the Dutch used to pay for grain, increased over time. This led to price reductions and overall Baltic trade declined.