Swedish Empire

Swedish Empire ( Swedish Svenska riket ; also: Sveriges stormaktstid , translated: Sweden's time of great power) denotes the term customary in Swedish historiography for the territory of the country in the 17th century. During the Swedish great power period from 1611 to 1721, Sweden conquered and held several important provinces in the Baltic Sea area outside of the actual national Sweden . This enabled the country to take a dominant position in the Nordic struggle for the Dominium maris Baltici . With a powerful army and fleet, Sweden became a defender of the Protestant faith.

Imperial history

Reich term

Sweden went through a strongly expansive phase in the early modern period, in which it gradually changed its state character and until the end of the 17th century it had the character of a multi-ethnic empire . The expansive early modern kingdom of Sweden had its borders far beyond the Swedish - Finnish language and cultural borders. Historians use the term “Swedish Empire” most often in this context.

Swedish historiography speaks in this context of “Sweden proper” and, in the case of the provinces, of the “Baltic provinces”.

prehistory

With the unification of the three kingdoms of Denmark , Norway and Sweden including Finland, the so-called Kalmar Union was concluded at the end of the 14th century , in which the three countries recognized the same king or queen with a seat in Denmark. Under the leadership of the Swedish nobleman Gustav Wasa , an uprising arose in 1521 that ended the Kalmar Union for Sweden (and for Finland ). Gustav Wasa seized power in the country and was elected the new king by the Diet in 1523 . As King Gustav I. Wasa (1523–1560) he then founded the modern Swedish nation state with central government, standing army , financial administration, hereditary monarchy instead of an electoral monarchy and the king as head of the Protestant church . Under the Wasa dynasty , Sweden became a major European power in the 17th century and largely dominated the Baltic Sea region.

The motives for expansion were varied. Among other things, the control of Swedish goods exports through the control of the Baltic Sea trade played a role as well as a specific military concept that included the opposing coasts. The internal weakness of neighboring countries, political and commercial goals and the successes achieved in earlier wars led Sweden to further wars of conquest. When succession disputes weakened Russia's strength with the so-called Smuta since 1598 and Poland-Lithuania was exhausted by a war in the south, an advantageous foreign policy situation arose. Only Denmark was on a par with Sweden in terms of strength. Charles IX took advantage of the chaos in Russia and re-launched war operations against Russia. So the balance of power in Northern Europe slowly shifted in favor of Sweden. It became the most powerful and most expansive empire in the north, even if its population was only around 750,000 around 1600 and it was still an agricultural country despite excellent raw material deposits. Although it was in a favorable position when it came to raw materials such as copper, iron and wood, the experts for the management of the rich deposits were still lacking.

Since 1604 the Danish king Christian IV pushed for a war against Sweden to stop its expansion. The Danish Imperial Council wanted a negotiated solution. In 1611 the Danish monarch declared war on Sweden. He hoped for a quick victory, especially since the neighbor was still involved in armed conflict with Poland. The Danish Navy blocked the Swedish coast. Christian IV invaded southern Sweden with an army, but encountered bitter resistance. On August 2, 1611, the Swedish fortress of Kalmar fell . The 61-year-old Swedish King Charles IX. died on October 30, 1611 and his son Gustav Adolf succeeded him. With him the Danish monarch grew into a difficult opponent.

Obtaining great power status

Under Gustav II Adolf

The beginning of the Swedish Empire is dated with the coronation of Gustav Adolf II in 1611. He took office at the time of the so-called Kalmark War against Denmark, which could only be ended two years later under tough peace conditions. Although Gustav Adolf was not yet able to prove his qualities as a military leader in this war, the Danish troops, mostly mercenaries, did not achieve any decisive success in Sweden. The local farmers waged a kind of partisan war against them. The Danish campaign in the summer of 1612 turned into a fiasco. It was only thanks to the superiority of his navy that Christian IV. That peace negotiations were initiated in November 1612. In the Treaty of Knäred , Sweden undertook to pay one million thalers. The war indemnity was to be paid off in six years. From then on, Swedish merchant ships also had to pay the sound tariff.

Gustavus Adolf's position of power was restricted by the political say of the Reichstag and Council. He was therefore primarily dependent on the productive collaboration with Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna , with whose help he modernized the then impoverished country. In the years that followed, Gustav-Adolf drove forward numerous reforms in the country that affected the education system, administration and also the Reichstag and Council. He carried out an exemplary administrative reform of both the provincial as well as the central administration, reorganized the tax system and created its own Imperial Court of Justice, which was to finally administer justice according to a verifiable court system without royal participation; however, the king reserved the right to possibly overturn a judgment ( cassatorial decision ). During this time, in addition to the comprehensive reform of the army system, modern accents were also set in the education and legal system. The king recognized for the first time the importance of targeted social legislation . Due to the socially tense situation, Gustav Adolf issued a law on the poor in 1624, in which he forbade begging but had compulsory work organized for beggars. A large hospital had to be built in every province (Län) . The Stockholm guilds were obliged to set up a house for 100 children in need. Elementary schools were promoted and, instead of Latin schools , humanistic grammar schools with comprehensive higher education were introduced in Sweden.

At the beginning of his rule, Sweden was in the Ingermanland war with Russia. The conflict ended in 1617 with the Peace of Stolbowo , which brought Sweden East Karelia and Ingermanland and which kept Russia completely away from the Baltic Sea. The border was subsequently considered safe, and a long period of peace followed in the east. After the Peace of Stolbowo, Gustav II Adolf concentrated on a war against Poland. He considered Poland the main enemy, as Sigismund continued to pose a threat to the Swedish crown. During the war with Poland (1621–1629) in 1621, Gustav II. Adolf occupied Riga, and later Sweden got several other port cities under his control. The French, i.e. the ruling, great Cardinal Richelieu , brokered an armistice in the person of the diplomat Baron de Charnacé in September 1629, the preliminary peace of Altmark was concluded, which was valid for six years. Poland saved its honor, Sweden retained de facto control of Livonia north of the Drina and the right to levy customs duties in the Prussian ports for six years, which generated significant income for the coming war on German soil. The treaty showed that neither Sweden nor Poland could achieve a military victory in the war. The armistice was made possible by the general exhaustion of both parties and marked a strategic stalemate. The result was far more positive for Sweden than the military situation had promised. Shortly before the end of the armistice, Poland and Sweden agreed in Stuhmsdorf on September 12, 1635 to continue the armistice. Relations with Poland were finally settled in 1660 when Poland gave up its claims to the Swedish crown.

In the Thirty Years War

The Swedish king observed the events of the Thirty Years War very carefully at this time. After Denmark had finally left the war and the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II seemed to have reached the height of his power, Gustav Adolf was ready to act. In 1630 Gustav intervened on the Protestant side in the Thirty Years' War. Already in 1627/28 the Stockholm Reichstag gave the basic approval to join the war and on January 18, 1629 the decision followed to conduct it offensively, i.e. on German soil. The reason often cited later on, wanting to protect the Protestant fellow believers against the Catholic Habsburg claims to omnipotence, manifested in the Edict of Restitution , was propaganda. There are different approaches to analyze the reasons for the Swedish entry into the war. There is a high probability that Gustav II Adolf recognized the uncertain situation in the empire and tried to use it. The Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna and Johan Skytte had advised the king against waging a war in the Holy Empire, but the high nobility had clear advantages through the war. The important customs revenues from the estuary and ports were very important to Sweden. Preserving these or acquiring new ones may have led to intervention. The Swedes were particularly interested in the mouth of the Oder.

On July 6th 1630 the king went ashore in Peenemünde . A fleet of 129 ships had brought him and his 13,000 soldiers across the sea within a week. Additional mercenaries from Finland, the Baltic States and Stralsund strengthened the army, which received no resistance from the imperial side. Gustav-Adolf forced several princes of Northern Germany into an alliance treaty and was seen by large parts of the Protestant population as liberators and saviors. Wollin was conquered on July 6th and Stettin on July 9th . The latter city fell with no real defense. By the end of 1630 the Swedes had practically all of Pomerania in their hands. The conquest continued in the spring. On April 3, 1631, the Swedes attacked the city of Frankfurt an der Oder, which was allied with the emperor, after the main imperial power under Tilly had moved west shortly before. In the same year they also won the famous (first) battle of Breitenfeld and penetrated into the Rhine Valley and Bavaria. On January 23, 1631, the Treaty of Bärwalde was signed between France and Sweden . This was an alliance treaty against the Habsburg emperor. Sweden pledged to bring more than 30,000 soldiers to Germany, while France paid some of the costs. After Gustav had defeated the emperor's troops time and time again, he rose to become the leader of the Protestants. Although it fell in 1632, the war still lasted over ten years. After the king's death, his chancellor, Count Axel Oxenstierna, headed the guardianship government for the underage king's daughter Christine and continued the political course. From 1644 the Swedish war aims were restricted by the Regency Council: the rule in the Baltic Sea area was to be secured, while further conquests in Germany were refrained from.

Under Christine and Karl X. Gustav

Christine ascended the throne in 1644 . As Queen, Christina promoted the arts, was in close correspondence with many scholars and called, among others, René Descartes to Stockholm. The turn to France as a continental ally was reflected in court culture, Christina attracted many French artists, especially musicians for the court orchestra, to Sweden.

With the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, Sweden acquired large parts of Pomerania, Rügen, Wismar, the duchies of Bremen and Verden. The Swedish monarch received three votes in the Assembly of the Holy Roman Empire and consolidated Sweden's position as a military power in the Baltic Sea region. At the same time, the Torstensson War between Sweden and Denmark was fought . Denmark ruled over what is now southern Sweden and imposed high tariffs that had to be set up for the passage of the Øresund . At the beginning of the 17th century Denmark was still imposing peace conditions on Sweden according to its own ideas, but at the time of the Thirty Years' War, Sweden was devastating Denmark. In 1645 the Peace of Brömsebro was signed. Sweden's goals were primarily commercial, but it also received territorial gains. Denmark temporarily had to cede large areas of Norway and the islands of Ösel and Gotland to Sweden. Sweden had achieved supremacy in the Baltic region. Christian IV was defeated.

Even though the Swedish troops simply captured numerous works of art in the name of Queen Christina towards the end of the Thirty Years War, for example during the so-called Prague art theft in 1648 , in which numerous pieces from the art collection of Emperor Rudolf II were transferred to Sweden, the other acquisitions and the pomp with which Christina liked to surround herself, the Swedish court faced enormous financial difficulties. Around the year 1650, Christina's reign was increasingly in crisis. Although she was officially crowned Queen of Sweden in October of this year, she saw herself no longer up to the tasks of a queen, felt constricted and toyed with the idea of abdicating. In 1654 Queen Christine abdicated in favor of her cousin Karl X. Gustav .

Charles X Gustav ascended the throne under difficult circumstances. The finances of the state were in great disorder, the national debt amounted to 5 million Reichstaler, the most profitable possessions of the crown were given to the favorites of the former queen and the income of the crown was therefore very limited. Above all, the new regent tried to put things in order and reform the finances, and he also restricted his own court.

Charles, who continued the policy of military aggression of his predecessors and ruled Sweden until 1660, declared war on Poland ( Second Northern War 1655–1660). After an initially rapid military advance in 1657, which brought Poland to the & # 132; brink of state collapse & # 147; brought on the defensive in 1657/58, not least triggered by the & # 132; change of front & # 147; of the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm through the Treaties of Bromberg and Wehlau in September / October 1657 and the annexation of Austria to the anti-Swedish coalition in 1658. At the end of 1658 it was foreseeable that the war could not be decided by military means.

In 1658 Charles X invaded Denmark and conquered the provinces in southern Sweden that Denmark had retained in the 16th century. After his victorious campaign from Holstein via Jutland to the Danish islands, Charles X Gustav forced the Danes to make the Peace of Roskilde (February 1658). Denmark had to cede Scania, Blekinge , Halland and Bohuslän to Sweden. Denmark lost sole control of the Oresund , the strait between Denmark and Sweden. Nevertheless, Karl Gustav kept his army under arms. Instead of resuming the war in Poland as expected, however, Charles X Gustav broke the peace with Denmark, landed his army on the island of Zealand in August 1658 and began the siege of Copenhagen. After the unsuccessful storming of Copenhagen in 1659, Karl X. Gustav had to be ready to make peace with Denmark under pressure from the Netherlands, France and England; He died in Gothenburg before he could begin negotiations with the Swedish parliament. It was not until the guardianship of his underage son Charles XI. it was reserved to end the wars with Poland and Denmark with the peace treaties of Oliva and Copenhagen (1660). In the Peace of Oliva in April 1660, Sweden's claim to Livonia and Estonia was formally confirmed. The peace treaties of 1660/61 brought the & # 132; Baltic Sea area into a state of relative stability & # 147;. However, no problem between the neighbors could be regarded as permanently resolved.

Under Charles XI. and Charles XII.

Sweden in particular had to fear the post-war situation, because the revision tendencies of the neighbors Denmark, Brandenburg, Poland and Russia affected by Sweden's expansion had hardly remained hidden during the peace negotiations on Oliva. The legacy of the warlike era of the rise of great power for the peaceful period of securing great power after 1660 was an obvious dilemma: Sweden was still very unfavorable in terms of its structural prerequisites for these foreign policy security tasks, i.e. for maintaining a large military potential in their own country.

Under Karl's son and successor, Karl XI. , Sweden allied with King Louis XIV of France and thus took part in the Franco-Dutch Wars of the late 17th century. Through the alliance with France, Sweden was drawn into a war against Denmark and Brandenburg-Prussia . In 1675 the Swedes suffered a heavy defeat by Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg , in the battle of Fehrbellin . After the defeat by Brandenburg-Prussia in Fehrbellin, Sweden's precarious situation also became evident abroad. The military setbacks of the Swedes continued with the sea battle near Öland on June 1, 1676, when the newly built admiral ship Kronan was destroyed in a very short time. On May 31, 1677, the Swedes also lost the sea battle at Lolland . After these losses, Denmark ruled the Baltic Sea. At the same time, the Danes on the land front had also recaptured Scania .

On land, the army was Charles XI. For a long time not more successful than at sea, because the turning point for the Swedish king came with the battle of Lund , which is described as one of the cruelest in Swedish history and in which half of all soldiers on the Danish and Swedish sides were killed . Within three years, Charles XI. then push the Danes out of Skåne again, even if this was only possible with very great losses. With the Peace of Saint-Germain and the Peace of Fontainebleau on August 23, 1679, Sweden got back all lands lost in the war.

After the peace treaties of 1679, Karl devoted himself to internal reform, the reorganization of the army and the administration in the sense of absolutism , and in doing so shook fundamental Swedish rights. He reorganized the Swedish government, downgraded the Imperial Council to the advisory Royal Council and took over the legislation and foreign policy that had previously been with the Reichstag. Under the pressure of the financial restructuring of the household and with the help of the peasants, the citizens, the officers and the lower nobility, Karl confiscated all large estates and goods of the nobility in a comprehensive reduction in 1680 and finally transformed this class into a nobility of officials, who in all matters was subject to the king. Charles XI. carried out the reduction in Livonia without the consent of the state parliament by referring to the reduction resolution of the Swedish Reichstag of 1682 and also to the view of the Swedish Reichstag that the reductions are a matter for the king regardless of the constitutional positions of the Baltic provinces in the empire. In the military sector, he made himself independent of the authorization of the now insignificant Reichstag by making the position of soldiers an obligation for the peasants in the division work . Charles XI. became a powerful sole ruler. When he made important decisions, he listened to the country's estates . His son and successor Karl XII. left behind Charles XI. 1697 a reformed absolutist superpower state and a reorganized and effective army. The situation changed when, after his death in 1697, his son Charles XII. was proclaimed sovereign ruler at the age of 15. He was stubborn by nature and only called the estates to a meeting once. He appointed his favorites for the offices.

The end of the great power era

At the beginning of the 18th century , Tsar Peter I permanently questioned the military and geostrategic supremacy of Sweden in the Baltic Sea region , the Dominium Maris Baltici . The Great Northern War began in Livonia in 1700 when nobles who had resisted the confiscation of their property started an uprising and demanded the annexation of Poland. This took Saxony-Poland , Russia and Denmark as an occasion to allied against Sweden.

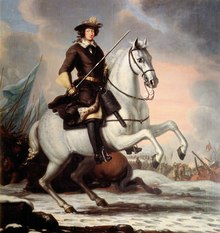

In the Battle of Poltava in 1709, King Charles XII. (1697–1718), who was considered one of the most famous military leaders of the time, suffered a catastrophic defeat against Tsar Peter I. This broke a myth about Sweden as a military power. The European great power Sweden, considered invincible, had to give up its place to a new player in the concert of the European great powers. Territorial losses followed. In 1710 the Russian army occupied the Swedish provinces of Swedish Livonia and Swedish Estonia as well as the southeastern part of Finland around the city of Vyborg . The Swedish territories Swedish-Ingermanland, Kexholms län had already been conquered in 1703/04. The end of the Swedish great power position is set with the loss of important Baltic territories in the Peace of Nystad 1721, which ended the Great Northern War .

Consequences and consequences of great power politics

The great military effort to maintain a supranational empire resulted in the deaths of 300,000 young men outside of national Sweden between 1620 and 1720 . This is all the more important because the total population of the Swedish Empire was no more than two million people during this period. Swedish research on the history of demography suggests that by the end of the 17th century every third or fourth man in Sweden-Finland who reached adulthood died in connection with the military campaigns.

Incidents of war

Sweden fought 12 wars between 1600 and 1720, of which Sweden lost only the last.

| phase | Beginning | The End | Phase designation |

|---|---|---|---|

| war | 1600 | 1618 |

Polish-Swedish War (1600–1611; 1617–1618), Ingermanland War (1610–1617), Kalmar War (1611–1613) |

| peace | 1618 | 1621 | three years of peace |

| war | 1621 | 1629 | Polish-Swedish War (1621-1625; 1626-1629) |

| peace | 1629 | 1630 | a year of peace |

| war | 1630 | 1648 |

Thirty Years' War : * Swedish War (1630–1635), * Swedish-French War (1635–1648), * Torstensson War (1643–1645) |

| peace | 1648 | 1654 | six years of peace |

| war | 1654 | 1660 |

First Bremen-Swedish War 1654, Second Northern War (1655–1660) |

| peace | 1660 | 1666 | six years of peace |

| war | 1666 | 1666 | Second Bremen-Swedish War 1666 |

| peace | 1666 | 1674 | eight years of peace |

| war | 1674 | 1679 | Northern War (1674–1679) |

| peace | 1679 | 1700 | 21 years of peace |

| war | 1700 | 1720 | Great Northern War (1700-1720) |

From 1600 to 1720 Sweden was 45 years at peace (37.5 percent time share) and 75 years at war (62.5 percent time share). The longest period of peace lasted 21 years from 1679 to 1700. The longest lasting war period lasted 20 years from 1700 to 1720.

geography

The Swedish Empire completely covered what is now Sweden, Finland, and Estonia. In addition, there is historical Western Pomerania (today's district of Vorpommern-Rügen and district of Vorpommern-Greifswald ) and parts of today's Lower Saxony ( district of Stade , district of Rotenburg (Wümme) , district of Cuxhaven , district of Osterholz , district of Verden ) including the municipality of Wismar in Germany, the western part of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship ( Powiat Policki , Świnoujście , Powiat Kamieński , Szczecin ) the northern part of Latvia (Central Livonia) and part of the Russian Republic of Karelia and Leningrad Oblast . Together this results in an area of around 900,000 to 950,000 square kilometers. At the time, Sweden was about the same size as Poland-Lithuania and, after the Tsarism of Russia, the Ottoman Empire and Poland-Lithuania as a state, it was the fourth largest area in Europe.

The provinces of Dalarna and Uppland formed the heart of Sweden. Gothenburg offered Swedish trade the only direct access to the North Sea .

Dominions of the Swedish Empire

The Swedish Dominions were territories within the Swedish Empire, which belonged to the Crown but were never considered part of actual Sweden or the central state as belonging. In their historiography, today's territories refer to this time of foreign rule as the Swedish time .

- Baltic Dominions

Between 1561 and 1629, Sweden conquered several provinces on the eastern Baltic coast . All conquests were lost in 1721.

- South Swedish Dominions

In the Peace of Brömsebro in 1645 and the Peace of Roskilde in 1658, Sweden expanded south. The newly acquired provinces retained their ancestral rights and privileges and were gradually incorporated into the Swedish central state after 1721.

- Continental Dominions

After the Thirty Years' War in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, Sweden gained further provinces on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire . By 1815 all territories were lost again.

population

In the 17th century the Swedish Empire showed a high degree of cohesion and unity among the social classes. Unlike in Central Europe during this period, the city network and urban structures in the Swedish Empire were poorly developed, which prevented the unification of the forces of peasants and citizens against the central authority. The nobility was also largely integrated into the government or the army. Denominationally, the empire was homogeneous, which meant that religious conflicts were absent and the country was easy to govern. Early modern Swedish society had the ability to engage in mutual dialogue, and this and the state's social control reduced the likelihood of revolts against the central authority.

Demographics

The total population of the empire was 1.25 million in 1620. In 1660, at the time of the greatest territorial expansion, the Swedish Empire already had 2.5 million inhabitants. Sweden had thus been able to significantly double its population in 40 years through conquests.

The population center of the Swedish Empire was in central and southern Sweden. Other densely populated areas were the German possessions. Large parts of the country, on the other hand, were almost deserted.

- In 1697 the population of Sweden was 1.376 million people.

- Finland's population in the 17th century was 350,000.

- The population of Swedish Estonia is estimated at 280,000 in 1698.

- The Swedish Livonia province had a population of 142,000 Latvians in the second half of the 17th century.

- An estimated 100,000–150,000 people lived in Swedish Pomerania around 1700. Bremen-Verden numbered around 100,000 people.

- In 1664 there were just 15,000 people in all of Swedish-Ingermanland . Karelia will also have been almost uninhabited.

Cities and urban centers

Location of the Swedish cities with more than 5000 inhabitants around 1700 |

The Swedish Empire was a poorly urbanized country. The few cities in the Swedish Empire had a relatively small population. Stockholm , which experienced a large-scale urbanization program in the 17th century, was by far the largest city with 55,000 inhabitants around 1690, followed by Riga on the other side of the Baltic Sea. Nevertheless, there were also large cities on the Baltic Sea. Compared to the Swedish cities, the non-Swedish cities bordering the Baltic Sea had large populations for European standards at the time. In the 17th century , Danzig had 80,000 inhabitants. Königsberg reached around 50,000 inhabitants. Rostock had around 8,000 inhabitants, Lübeck around 30,000 inhabitants and Flensburg had 6,000 inhabitants. Copenhagen had as many inhabitants as Stockholm.

With the urbanization phase in the late 17th century, the position and reputation of the cities, with the exception of Stockholm and Gothenburg, hardly improved. Most of the rural residents did not cover their own economic needs through trade and commerce from the cities, but through the large surplus of agriculture and their own agricultural businesses . The strict trade law and the exchange of goods with other cities and countries were not enough to provide a stable basis for the growth of old and new cities in Sweden.

It was not uncommon for artisans to make up between 20% and 40% of the urban population. From this it can be concluded that in contrast to German cities such as Stettin or Lübeck, society in Sweden was characterized by a weak bourgeoisie. Settlements and villages in Sweden were usually characterized by a collection of farms belonging to free farmers and landed property belonging to the landed gentry. There were hardly any clear differences between urban and rural life.

The largest population centers in the Swedish Empire around 1700 were:

- Sweden and Finland

Sweden (80) and Finland (20) together had 100 urban settlements, of which around 1700 only one had more than 10,000 inhabitants. Ten percent of the population lived in these 100 urban settlements. That was around 150,000 people. The approximate average size of a median city was between 1300 and 1500 inhabitants. From the mid-16th century to the mid-17th century, 40 new cities were founded in Sweden. In Finland, 13 new cities were added during the same period.

- More than 10,000 inhabitants: Stockholm

- More than 5000 inhabitants: Gothenburg , Karlskrona , Falun , Norrköping , Uppsala , Åbo

- Ingermanland, Karelia, Estonia, Livonia

Karelia’s capital, Kexholm , had fewer than 1000 inhabitants. The main places of Ingermanland were Nyen and Nöteborg , which also had less than 1000 inhabitants. Livonia and Estonia, on the other hand, had a total of two dominant cities that were also of supraregional importance for trade and transport.

- More than 10,000 inhabitants: Riga , Reval

- More than 5000 inhabitants: none

- other urban centers: Narva , Dorpat

- Swedish Pomerania, Bremen-Verden, Wismar

The northern German possessions were densely populated by Scandinavian standards, so there are several urban centers and a total of 26 cities in the provinces. Swedish Pomerania had a total of 22 cities. For Sweden, Stralsund was of great military and strategic importance due to its good defensive position and its proximity to the Swedish mainland and served as a gateway for military interventions on German territory. Around 1700, Wismar was considered the strongest fortress in Europe. Besides Stade, there were only two other cities in Bremen-Verden : Buxtehude and Verden, which were only of local importance.

- More than 10,000 inhabitants: Szczecin

- More than 5000 inhabitants: Stralsund

- other urban centers: Greifswald , Anklam , Stade , Verden , Wismar

education

In addition to the schools maintained by the church, Gustav II promoted the establishment of schools in which the natural sciences and statecraft were in the foreground, but the church's influence was still strong in these schools. The school regulations, which were drawn up at the time of Queen Christina in 1649, were a significant renewal, but their implementation failed due to a lack of financial resources. The schools were divided into four-class elementary schools to be established in each city. The school regulations provided for secondary, also four-class grammar schools. Elementary schools led to grammar schools and over half of their teaching hours were devoted to Latin . The first grammar school in Sweden was established in Västerås in 1623 . A further eleven grammar schools followed by 1649. Thereafter, their number stagnated until the end of the great power period in Sweden. The illiteracy decreased significantly.

- Universities

Around 1700 there were the following universities in the Swedish Empire:

- University of Greifswald

- Uppsala University

- Lund University (since 1666)

- University of Dorpat (since 1632)

- Turku Academy (since 1640)

Social structures

On the one hand, the 17th century in Sweden was characterized by the relative stability of social structures inherited from the Middle Ages; On the other hand, the centralizing and unifying Swedish state, striving towards absolutism, set in motion processes of social change that led to the emergence of new groups and strata . This included the officer corps and the officials of the growing administrative apparatus.

- The officers found themselves at the center of an immense distribution system, as the Swedish state allocated a disproportionately large share of social resources to warfare at the end of the 17th century. Thus the military elite was also socially favored by the state apparatus and grew quantitatively.

- As the state apparatus grew in the course of the 17th century, more and more people from other social classes had to be ennobled in order to be able to meet the status requirements associated with civil service. From the second half of the 17th century to around 1720, a relatively poor official nobility grew up in Sweden , which in comparison to many other countries was economically more dependent on civil service .

Above all, Sweden was a peasant country in the 17th century . More than 90 percent of the population lived in the countryside and on agriculture. Serfdom or other unfree forms of ties to noble landlords never existed in Sweden. The fact that the farmers were last represented as the fourth stand in the Reichstag was unique in Europe. More than a third of the property was in the hands of free farmers. Despite the extremely heavy burden of the excavations, the farmers were able to increase productivity by adapting their own economy to wartime conditions, which led to an economic boom and population growth at the end of the 17th century.

The low urbanization and the relatively weak position of the cities reduced the social, economic and political position of the bourgeoisie . The elite among the citizens were almost always connected to the iron and copper trade, most of them living in Stockholm. The cities received no nationwide privileges from the crown because of their historically grown rights. Rather, the monarch confirmed the particular right to freedom of each individual city. Swedish city law dates back to the 14th century and largely unified urban freedoms. The Stockholm mayor became the phrasebook of the bourgeoisie. Since 1650, this had 80 to 100 members in the Reichstag.

The nobility , who had received extensive privileges in 1612, had a monopoly on all higher offices. At the same time, this class boundary was permeable, so that the number of nobles increased fivefold through new ennobling in the 17th century. In the Baltic provinces, aristocrats were given large land holdings on which large-scale, monetary-oriented goods and manufacturing industries could be operated. As a result, the nobility tripled their land holdings in the 17th century. The crown devoted a great deal of energy to limiting the power of the nobility. Any attempts by the nobility to restore the power of the Imperial Council failed until the 1630s. Only after the death of King Gustav II Adolf (1611–1632) in 1632 and due to the initial immaturity of his successor Queen Christina I (1632–1654) was the nobility able to establish a new constitution in 1634. In the middle of the 17th century, the power of the nobility in Sweden had reached its peak. The nobility were now the most influential layer in Sweden's early modern class society . Under the pressure of the financial restructuring of the budget, the parliament of 1680 and 1682 led to the disempowerment of the Swedish aristocracy , whose goods were partially confiscated by the crown. In doing so, the crown also wanted to free itself from the economic and political influence of the great families of the empire. Only the so-called reduction (repatriation) at the end of the 17th century brought numerous former domains back into the hands of the crown. In the end, the state again had an average of two-thirds of all goods in the empire. The vanishingly small state incomes from the feudal estates in the Baltic provinces before the reduction were converted into lease payments after the confiscation of the estates, which made up a third of the total reduction income in the Swedish Empire. The Krone has now been able to use this enormous resource for acute needs and needs that have long been neglected.

ethnicities

The Swedish state has been moving towards a multi-ethnic empire since the beginning of the 17th century. In addition to Swedes , mainly Finns , Estonians , Latvians , Sami and Germans lived on the territory of the Swedish Empire. In addition, there were Danes , Norwegians , Lives , Karelians , Woten , Ischors , Ashkenazi Jews and Roma in smaller numbers .

religion

Almost all residents were members of the Swedish Lutheran Church . The Church of Sweden was the state church of Sweden. In the 17th century, Lutheran Orthodoxy became fully established, while Pietism took only few roots. The church gradually regained its old strength. It developed into a solid pillar of central power. However, she strictly observed adherence to pure Christian teaching.

migration

The immigration of foreign skilled workers and the influx of foreign capital, especially from the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire, were actively promoted by the state. Famous migrants in Sweden were for example Alexander Erskein , Robert Graf Douglas , John Hepburn , Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven .

economy

Economic and financial policy

The position of great power put the Swedish economy to an unprecedented test. The Swedish administration tried to meet the need for money by following the principles of mercantilism . In order to increase the precious metal reserves , more was exported than imported in order to achieve a positive trade balance for the entire empire . For this, high tariffs were levied on goods imported from neighboring countries in the Baltic ports under Swedish rule . This was seen as a secure source of income for Sweden, but it represented considerable disadvantages for the states concerned. The Swedish customs barrier thus became a real trade barrier, despite the temporary increase in the number of visitors to the Swedish Baltic Sea ports. As a result, the neighboring countries were increasingly disapproving of Sweden. Russia in particular suffered from the Swedish policy of repression. The Swedish government tried again and again to obstruct or even destroy the northern trade route via the Russian port of Arkhangelsk in order to counteract a reduced frequency of its own trading centers.

The state monitored economic life and granted monopolies to certain areas in order to maintain a positive trade balance and to intensify the collection of taxes . Since money and precious metals were the basis of wealth, the main focus was on trade and economy, while the country's main livelihood, agriculture, was left to its fate.

When the great power had to maintain a large army and build a fleet, taxation rose. In addition to the property tax , new, occasional taxes were levied, but these remained permanent. The nobility were exempt from new taxes and the poll tax that every 15 to 60 year old had to pay.

Economic sectors

There was no significant agricultural surplus production in Sweden in the 17th century. Swedish agriculture in the early 17th century was characterized by small-scale farming and based on natural produce and was little capitalized. There was no large-scale goods economy. The farms suffered from constant wars and the annual evictions of soldiers. Livonia and Estonia, which were considered to be the production and export regions of agricultural products, freed the Swedish Empire from its dependence on grain imports and on foreign food markets. About half of the entire grain requirement in the Swedish Empire could be met by Livonia and Estonia alone.

In contrast, mining and forestry, in which the state was heavily involved with investments and profits, were profitable . In addition, the inflow of Dutch capital into Swedish trade and mining could stimulate local economic life; The development of Swedish mining would have been inconceivable without Dutch capital. As a result, Sweden became the largest copper producer in Europe. Falun was the dominant copper mining location in Sweden, accounting for 90 percent of the production volume. Also, iron and other metals essential to the war were won in state and private mines. On the one hand, they were used to equip the Swedish army, on the other hand, they were exported abroad in order to make trade profits. The share of metal products in exports was around 80 percent in the 17th century. The export of iron became more and more important. It grew from around 11,000 tons of bar iron in 1640 to 27,000 tons by the end of the century. The ore was processed in the iron factories outside the cities of Sweden. In addition to tools, iron implements, horseshoes , wheel fittings, chimneys and stoves, armor , stabbing weapons , cannons and other handicraft products were made. During the period of great power, hundreds of so-called bruks , industrial locations with iron works, emerged. In arms production , the company was Finspångs Styckebruk with production in Finspång as Sweden's largest exporter of guns significantly. Other companies were Holmens Bruk , Iggesunds Bruk , the Torsebro powder factory , Stora Kopparbergs bergslag and Brattforshyttan . Louis De Geer was considered the father of Swedish industry . Other flourishing export products from forestry were sawn timber , pitch and tar , which was exported to the shipbuilding companies of Holland and England. The state endeavored to concentrate handicrafts and trade in the cities, since there it was easier to monitor working life and to tax.

Finances

The world's first central bank , the Palmstruch Bank , was established in 1651. However, because the value of these first banknotes was not consistently covered by precious metal, the notes were devalued by inflation. The Reichsbank in Stockholm was established in 1668. It was created through the takeover of the Palmstruch Bank or Stockholms Bank founded by Johan Palmstruch in 1656 to prevent bankruptcy of the same. Initially, the Swedish Reichsbank was dependent on the decisions of parliament. In the 17th century, the central bank was forced several times to finance various wars for Sweden. In addition, the central bank also had to finance a strong economic expansion policy. All of this ultimately ended in high inflation. The currency was the riksdaler , which was launched from 1604. In July 1661, the first uncovered paper money in Europe was issued in Sweden . The minting of coins was standardized in the course of the 17th century with the introduction of a standardized copper coin base .

State

State and central government

The early modern European state was usually a conglomerate of different parts of the country, which in turn had their own corporations and constitutions . The central bracket formed the crown and the highest Reich authorities . In the case of the Swedish Empire, there was actual Sweden, which at the time was what is now Sweden. This formed the actual central state , within which the crown, or the monarch , had a kind of direct access.

The other corporate forces within the Swedish Empire, predominantly feudal and municipal institutions and Ritterschaften formed the counter-power to the crown and formed with her the entire state. These opposing powers had their own territorial bases and were only connected to the Swedish Empire through the person of the monarch. Otherwise they had extensive autonomies . This was particularly true of the Baltic provinces. The Swedish central state - today's Sweden - was accordingly restricted in its sovereignty.

As a result of political reforms, Sweden already had a rudimentary separation of legislative , judicial and executive branches in the 17th century .

ideology

The historical image of Gothicism which legitimized the position of great power prevailed and the formative self-image of the monarchs as " army kings" prevailed .

Royalty

The Swedish kingship strove for absolute rule in the 17th century. Through two guardianship governments of the high nobility from 1632 to 1644 and from 1660 to 1672, this objective could be postponed until Charles XI. In 1693 the absolute monarchy was finally introduced in Sweden.

executive

Sweden had a modern administrative structure and efficient authorities in the 17th century. This came about because the low population and economic power of the empire made a powerful surveillance apparatus necessary, which was geared towards the accumulation of resources and whose central elements were the military , the central government and the Lutheran Church. The establishment of this system required administrative reforms, new authorities and large numbers of well-trained civil servants .

The main designer of administrative structures in Sweden in the first half of the 17th century was Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna . This advocated a comprehensive co-responsibility of the nobility, which should be secured by a strong kingship. He converted the Reichsrat from a body that was only temporarily convened to a permanent government. On December 5, 1632, Oxenstierna submitted Sweden's new "form of government" to the Imperial Council. On July 29, 1634, the Swedish Diet confirmed the new "form of government". It was not a basic law or a constitution, but an administrative ordinance . As a source of Swedish constitutional law, it stood alongside land law and the royal oath, orders of succession to the throne and election or confirmation resolutions, and royal insurance. Their status as a source of law was not initially determined. In the end, however, the fundamental decision of 1634 remained. When the form of government was adopted in 1634 , Oxenstierna had the goal of preserving royal rights, securing the authority of the Imperial Council and preserving the freedoms of the estates, while at the same time the high nobility dominated the crown.

The document contained instructions for the Regency Council , Sweden's five-person government . According to this, the Swedish administration should be led by five collegially working Reich authorities: 1. The courts of Stockholm, Åbo , Dorpat and Jönköping , 2. The War College , 3. The Admiralty College , 4. The Chancellery responsible for foreign and domestic policy, 5. dem Chamber of Commerce . In the form of government of 1634 the guidelines of an official state were established. This created an alternative to the state controlled by the king. The administration and government of the empire were independent of the king . Instead, power over the empire lay in the hands of the high imperial offices. The form of government gives little information about the king and his powers. The Reichstag and the Reichsrat also became secondary figures in the form of government.

The statutes on regional administration followed the same pattern as the regulations for central administration. Here, too, the division of labor between different authorities and officials was very important. The new instructions for the Landshövding or governors who were responsible for the regional administrative districts (Sw. Län ) are also closely linked to the form of government of 1634 . The new instructions were issued in 1635. Up to this point the instructions are not uniform, but are different for each governor. Through the form of government, the Swedish Empire was divided into administrative districts (län). The local communities had room for maneuver and were not completely subordinate to the central leadership of the power state.

None of the following kings felt bound by this form of government and King Charles XI. (1660–1697) ended it in 1680. The constitution was formally repealed in the same year by the Reichstag. The constitutional form of government had to give way to the sole rule of the regent. He replaced the Reichsrat with a council subordinate to him in all matters. The position of the Reichstag was also weakened in the years that followed.

Judiciary

The creation of a total of five court courts in the Swedish Empire was primarily related to traffic and communication.

legislative branch

The political administration of Sweden was divided into the Reichsrat and the Reichstag . The Reichstag, divided into four estates, became a permanent constitutional organ in 1561. The four curiae that made up the Reichstag were made up of citizens , peasants , nobles and clergy . The members of the Reichstag were granted a say in decisions on political and religious questions, with the precise definition of their working methods taking place in 1617. The members of the Reichsrat, on the other hand, belonged to the high nobility . By the 1634 form of government, the number of members was fixed at 25.

Policy fields

External relations

In the 17th century, Sweden was part of a French alliance system, the Barrière de l'Est .

defense

In the 17th century, the state of Sweden and its political power depended on an efficiently functioning military system. From the reign of Gustav II Adolf to Karl XII. Army reforms, which were required by the respective war situations, were the focus of Swedish domestic policy. Even after Gustav Adolf had ascended the Swedish throne in 1611, the armed forces began to be modernized. In the 1620s this led to the formation of so-called provincial regiments, each recruited from a specific province. In 1634 it was decided to divide the army into eight cavalry and 23 infantry regiments. The Swedish army reform under Gustav Adolf was closely linked to the Orange Army reform . Especially the ideas of Johann VII. Von Nassau-Siegen , who had been in the Swedish service himself, shaped the reforms of Gustav Adolf, which provided for the arming and training of evicted Swedish residents. A model of raising the army developed in Sweden, which - unlike in almost all other European countries - was essentially based on the levy of local farmers and was referred to as the system of division . Since the reform of 1682, each of the Swedish landscapes has been required to maintain a regiment.

In the 17th century, all of Sweden was surrounded by a belt of fortifications along the empire's 3000 to 4000 kilometer long land border. If you take all territories together, over 100 fortresses , castles and fortifications protected the Swedish Empire.

In 1700 Sweden had 40,000 line soldiers. In addition, there were around 25,000 recruits who were mainly stationed in the Baltic Sea provinces. The Swedish navy comprised 38 ships of the line with a crew of almost 15,000 men, with Karlskrona as the fleet base. Sweden had an absolute numerical, but at the same time qualitative, maritime superiority over Denmark-Norway for almost the entire 17th century .

Communication, post, trade and transport

Sweden ruled large parts of the Baltic Sea for almost a century. The Baltic Sea functioned as a quasi-Swedish inland sea . This was made possible by the protection of the Swedish Navy . In the 17th century, travelers reached all areas of the empire by ship. The Swedish Post, the Postverket , set up regular shipping lines .

Swedish trade in the Baltic Sea was still controlled by the Dutch in the first half of the 17th century, but also by the British. But although the Swedish Empire was an outspoken export state compared to the shopping Netherlands and the English, the transport of Swedish goods was largely a matter for the buyers. Sweden produced, the Dutch and English transported. The merchant fleet was still small and insignificant around 1600. At the same time, Sweden made great efforts to become independent of the Dutch and their ships by building up a merchant fleet and promoting regional shipbuilding, for example in Narva. The Swedish merchant navy grew in importance; the Baltic Sea trade and the North Sea trade under Charles XI. was supported by 750 Swedish merchant ships. However, the expansion of the shipping capacities of the Swedish merchant fleets was caused by a simple change of flag by the Dutch shipowners and not by an increase in shipbuilding capacities in their own shipyards. The reason for this was the Anglo-Dutch sea wars of that time. The main competitor for the control of trade routes in the Baltic Sea remained Denmark.

Sweden had no postal system of its own until 1636 and was only connected to Europe via Denmark. Until the end of 1630, the crown farmers in Livonia were also obliged to transport royal mail, following the Swedish model , and since then the government administration has taken care of the transport. After the first initiatives of the Swedish central administration to set up a postal system in the Baltic Sea provinces that would be united with the rest of the empire in the 1620s, the provincial postal system fell into place again in the mid-1630s because the knights refused to bear the corresponding financial and personnel burdens . Attempts to revive and expand it, however, continued throughout the 17th century. The year of origin of a public Swedish postal system is given as July 28, 1636. King Charles XI. lifted the leasing system and set up the post office as a state transport authority by decree of January 7, 1677. From now on the postal connections were considerably improved, and soon there were 84 post offices in the country. In 1697, the Upper Postal Directorate in Stockholm was created in Stockholm as the highest postal authority.

The oldest newspaper that still appears today is Post-och Inrikes Tidningar , the official Swedish state gazette, which has been published continuously since 1645. This made it the first ever Swedish-language newspaper.

Culture

In the 16th century, Sweden was still a culturally underdeveloped nation. Only in the course of the political expansion in the 17th century did the country get a king and a noble class who consciously tried to take over cultural news from Europe. The Swedish dominance in the Baltic Sea region led to a European cultural import into the north of Europe. The cultural build-up of the monarchy attracted large numbers of artistic talent from the Netherlands, France, the Empire and England. These included: Sébastien Bourdon , David Beck (painter) , Jürgen Ovens , David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl , André Mollet , Simon de la Vallée , Justus Vingboons , Nicodemus Tessin , Jean Marot , Jürgen Gesewitz and many more.

Theater and literature

Compared to the theatrical history of Germany, France or England, no attempts, or only very tentative, attempts to develop a professional theater can be recorded in Sweden up to the middle of the 17th century. In the 17th century, however, theater life was brisk. However, the Swedish theater was carried out by amateur actors. There was a school and university stage based on the German model, which primarily served educational purposes. Various forms of courtly theater were also cultivated: lifts, ring races, court ballets, taverns, etc. The grand performances of the courts primarily served to teach the young Swedish aristocrats how to behave. Johannes Messenius wrote plays with mythical or historical themes. At the same time, Swedish poetry was created with poems by Lars Wivallius . In the second half of the 17th century, the ideas of the invaded Renaissance in the Swedish literature ( Georg Stiernhielm and Olaus Rudbeck ). Baroque tendencies can be seen in the works of Johan Runius .

music

Important court musicians of the Kungliga Hovkapellet were: Andreas Düben , Gustav Düben .

Building culture

Numerous new cities were founded in the middle of the 17th century. The new cities like Karlskrona or Karlshamn had a chessboard-like arrangement of the buildings around a central square. Urban planning activities were booming. However, Sweden at that time lacked a building culture that would meet the demands of being a great power . The rural architecture was considered unworthy and without architectural highlights in order to correspond with the strengthened self-esteem of a nation. In the search for a national style of their own, traditional forms were neglected and eclectic by the modern conceptions of architecture and town planning . The architecture in Sweden was no longer a legible indication of a historical development, but in the 17th century it became a means of expression for the glorification of God, King and State.

In Sweden, fortification building was given priority in the late 17th century. Architects such as Simon de la Vallée and Nicodemus Tessin realized the baroque architectural style in Stockholm, especially in church and monumental government buildings, as a representative form of expression for the most important political center in Swedish territory. The development of a self-confident bourgeoisie and its representative architecture as it was to be found in northern German cities was lacking in Sweden at that time. In return, the development of mansions , the residential buildings of the country nobility and the emergence of palaces for the Swedish aristocracy in cities show not only an effort to Europeanise Swedish architecture, but also illustrate the social order of the 17th century in Sweden, which gave the nobility a priority admitted. In many places, city palaces and mansions of the nobility with parks based on the French model were built. In terms of church construction, the baroque can be seen in the magnificent Katharinenkirche in Stockholm. The palace buildings of the 17th century reflect the wealth of the ennobled generals. Skoklosters slott and Läckö as Karlsberg Castle , Mariedal Castle , Castle Näsby , Stockholm City Museum , Drottningholm Palace and the Bonde Palace date from this period. Some of the great buildings and palaces that were supposed to symbolize the power of the country and its nobility, such as Riddarhuset , the Oxenstiernska palatset , the Tessinsche Palais and the old Reichsbank, were built in the 17th century .

literature

- Huntley Hayes, Carlton Joseph: Modern Europe to 1870, 1953, pp. 233f

- Roberts, Michael: The Swedish Imperial Experience 1560-1718, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-521-27889-8 , pp. 10f

- Cooper: The New Cambridge Modern History, CUP Archive, 1979, ISBN 978-0-521-29713-4 , pp. 408f

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Otfried Czaika, "Luther, Melanchthon and Chytraeus and their significance for the theological training in the Swedish Empire", in: Herman Selderhuis, Markus Wriedt: Denomination, migration and elite education: Studies on theological training of the 16th century, Brill, Leiden and Boston 2007, Pp. 53-83, here: 54

- ^ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 14

- ^ Arne Danielsson: Sébastien Bourdon's equestrian portrait of queen Christina of Sweden - Addressed to “his Catholic Majesty” Philip IV. In: Konsthistorisk Tidskrift / Journal of Art History. 58, 1989, pp. 95-108. doi: 10.1080 / 00233608908604229

- ↑ Maren Lorenz: The Wheel of Violence: Military and Civilian Population in Northern Germany after the Thirty Years War (1650–1700), Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2007, p. 10

- ↑ Maren Lorenz: The Wheel of Violence: Military and Civilian Population in Northern Germany after the Thirty Years War (1650–1700), Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2007, p. 317

- ^ Paul Douglas Lockhart: Sweden in the Seventeenth Century, Macmillan International Higher Education, 2004, p. 107

- ^ Robert Nisbet Bain : Charles XII, and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire: 1682-1789, GP Putnams̕ Sons, 1902

- ↑ https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/1881/file/militaer9_1_Btr02.pdf Mikko Huhtamies: The Swedish military colonies in the Baltic States during the so-called Swedish period of great power (1620-1720) - with special reference to Axel Oxenstiernas Grafschaft Wolmar-Wenden in Livonia, p. 32

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008, p. 390

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008, p. 390

- ↑ Frank Braun, Stefan Kroll : City system and urbanization in the Baltic Sea region in the early modern times: Economy, building culture and historical information systems: Contributions to the scientific colloquium in Wismar on September 4th and 5th, 2003, chapter: Sven Lilja: Scando-Baltic Urban Developments c . 1500-1800 (p. 48 - p. 88), LIT Verlag Münster, 2004

- ^ Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Wilfried Reininghaus: City and Crafts in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2000, p. 170

- ↑ https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/1881/file/militaer9_1_Btr02.pdf Mikko Huhtamies: The Swedish military colonies in the Baltic States during the so-called Swedish period of great power (1620-1720) - with special reference to Axel Oxenstiernas Grafschaft Wolmar-Wenden in Livonia, p. 33

- ^ Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Wilfried Reininghaus: City and Crafts in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2000, p. 171

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 383

- ^ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 379

- ^ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 379

- ^ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 379

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Little History of Sweden, p. 64

- ^ Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Wilfried Reininghaus: City and Crafts in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2000, p. 170

- ^ Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Wilfried Reininghaus: City and Crafts in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2000, p. 171

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Central State and Province in Early Modern Northeast Europe, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 13

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Little History of Sweden, CH Beck, 2012, p. 60

- ↑ Ralph Tuchtenhagen: Little History of Sweden, CH Beck, 2012, p. 60

- ↑ http://www.let.osaka-u.ac.jp/seiyousi/vol_6/pdf/JHP_6_2009_30-47.pdf Leos Müller: Swedish Shipping Industry: A European and Global Perspective, p. 34 in: Journal of History for the Public (2009) 6, pp 30-47 © 2009 Department of Occidental History, Osaka University. ISSN 1348-852x