Battle of Poltava

| date | June 27th jul. / 28. June swed. / 8. July 1709 greg. |

|---|---|

| place | Poltava , Tsarist Russia (now Ukraine ) |

| output | Decisive victory for the Russians |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Charles XII. |

Peter I. |

| Troop strength | |

| 20,000 men 32 cannons, 4 of them operational |

37,000–45,000 men + 3,000 Kalmyks 72 cannons, 28 of them operational |

| losses | |

|

6,900–9,234 dead and wounded |

1,345 dead |

1st phase: Swedish dominance (1700–1709)

Riga I • Jungfernhof • Varja • Pühhajoggi • Narva • Pechora • Düna • Rauge • Erastfer • Hummelshof • Embach • Tartu • Narva II • Wesenberg I • Wesenberg II

Arkhangelsk • Lake Ladoga • Nöteborg • Nyenschanz • Neva • Systerbäck • Petersburg • Vyborg I • Porvoo • Neva II • Koporje II • Kolkanpää

Vilnius • Salads • Jacobstadt • Walled Courtyard • Mitau • Grodno I • Olkieniki • Nyaswisch • Klezk • Ljachavichy

Klissow • Pułtusk • Thorn • Lemberg • Warsaw • Posen • Punitz • Tillendorf • Rakowitz • Praga • Fraustadt • Kalisch

Grodno II • Golovchin • Moljatichi • Rajowka • Lesnaja • Desna • Baturyn • Koniecpol • Weprik • Opischnja • Krasnokutsk • Sokolki • Poltava I • Poltava II

2nd phase: Sweden on the defensive (1710–1721)

Riga II • Vyborg II • Pernau • Kexholm • Reval • Hogland • Pälkäne • Storkyro • Nyslott • Hanko

Helsingborg • Køge Bay • Gulf of Bothnia • Frederikshald I • Dynekilen Fjord • Gothenburg I • Strömstad • Trondheim • Frederikshald II • Marstrand • Ösel • Gothenburg II • Södra Stäket • Grönham • Sundsvall

Elbing • Wismar I • Lübow • Stralsund I • Greifswalder Bodden I • Stade • Rügen • Gadebusch • Altona • Tönning II • Stettin • Fehmarn • Wismar II • Stralsund II • Jasmund • Peenemünde • Greifswalder Bodden II • Stresow

The battle of Poltava on June 27th jul. / 28. June swed. / 8. July 1709 greg. was the decisive battle of the Russian campaign of Charles XII. in the Great Northern War between Russia under Peter I and Sweden under Charles XII. The battle marked the turning point of the war in favor of the anti-Swedish coalition.

After the extremely harsh winter of 1708/1709 , the weakened Swedish army resumed operations in the spring of 1709 and began the siege of the Poltava fortress , an important trading center and military depot on the Vorskla . Meanwhile, a superior Russian army was preparing for the decisive blow against the Swedish invaders. In the battle, 37,000–45,000 soldiers of the Russian army fought with 28 artillery pieces. Opposite them were 20,000 Swedish soldiers with four operational guns.

The Swedes suffered defeat and fled the battlefield. The remnants of their army were found by Russian units a few days later and had to capitulate. Only Charles XII. together with a small number of followers, they managed to flee to the Ottoman Empire .

prehistory

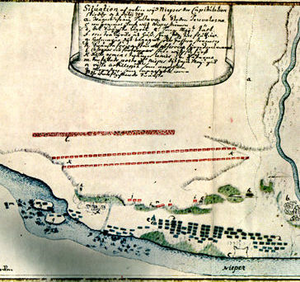

Location of the battlefield |

Early Swedish victories at Copenhagen and the Battle of Narva in 1700 had temporarily thrown Denmark and Russia out of the war. However, King Charles XII was. unable to bring the war to an end. It took the Swedish king another six years to force the remaining opponent August of Saxony-Poland to peace. In the meantime, Tsar Peter I had rebuilt his army . The new Russian army now had well-trained infantry , as was necessary for the use of linear tactics , and modern firearms.

After Karl occupied Saxony in 1706 and left the war for the time being, in the spring of 1707 the King of Sweden marched from Saxony via Poland towards Moscow to defeat the last Swedish opponent of the war. Karl, at that time before Poltava the first general in Europe and a brilliant troop leader, was determined to resolve the historical conflict with Russia for supremacy over Poland and Northern Europe with a major offensive against Moscow. Since his previous victories against the Russians, for example in the battle of Narva or the blockade of Grodno , he despised the Russians and assessed their combat strength as only low. He had increased his main army to 36,000 soldiers (out of a total of 44,000 men). The entire invading army consisted of 60,000 men, including 8,000 Swedish recruits from Poland and at times 16,000 Polish soldiers from the allied princes Leszczyński and Potocki . But the Polish contingent lost in the battle of Koniecpol and could not reach Charles' invading army.

The starting point of this offensive was the border area between Lithuania and Russia, where Charles XII. on September 10, 1708 at Smolensk had led his last campaign. Charles XII. marched along the main route through the aristocratic republic to Moscow. The Russians tried to push him south to prevent him from advancing into the capital. To this end, they burned everything on the land that could serve the Swedes to supply, and weakened the Swedish offensive forces on the advance through forests and rough terrain with small raids. When the Swedes were halfway to Moscow, the king ordered the advance to be stopped due to a lack of supplies and to move to the south of tsarism , where he also hoped for the support of the Zaporozhian Cossacks under Hetman Ivan Masepa . A revolt of the Dnieper Cossacks against the rule of the Tsar had broken out there. In October 1708 Masepa allied with Karl XII. and concluded a military-political pact with Sweden. Only 3,000 Cossacks of the Cossack army joined him. According to the pact, Sweden undertook to provide military support to the Zaporozhian Cossacks and not to sign a peace treaty with Russia until the Zaporozhian Cossacks were completely liberated and all their rights were restored.

A Swedish supply column intended for the main army under the command of General Lewenhaupt suffered in the battle of Lesnaya on October 9, 1708 greg. heavy losses, what the supply of the army of Charles XII. additionally made difficult. He gave up the march to Moscow for the time being and marched further south. There he hoped to solve his serious supply problems and then be able to carry out the attack on Moscow from there. But the Russian army moved parallel to the Swedes and blocked the enemy from attacking. While the conquerors were unsuccessfully moving towards Moscow, Peter the Great had fortified Poltava , which was an important strategic center in southern Russia.

Hibernating undermined the combat capability of the Swedish army. Repeated offensives by Russian divisions and partisans, lack of food, ammunition, fodder and uniforms - all of this forced the Swedes to use a different style of fighting. The cold of the Russian winter from 1708 to 1709 , the hardest of the century, also cost many Swedish soldiers their lives because they were insufficiently dressed and poorly cared for. Your military doctors were busy amputating frozen limbs. The loss of horses was so great that only four cannons of the entire artillery could be kept. The invading army of Charles XII. sank to a total strength of 25,000 to 30,000 men by the time of the great battle.

course

Siege of Poltava and preparation for battle

From the end of February 1709 the main Swedish army stood between the Psjol and the Worskla , the northern tributaries of the Dnieper , with its headquarters in Budishchi north of the Poltava fortress. The king did not want to accept the proposal of Charles' advisers to withdraw to Poland because of the many failures and lack of ammunition. In the spring, Charles XII began. instead, to resume the offensive. His first action was the siege of the city of Poltava in early April 1709, which he carried out with 8,000 men. The strategic sense of the royal combat tactics was that from here the advance should take place over the Worskla eastwards in the direction of Kharkiv - Belgorod - Kursk on Moscow. Poltava is located on the Vorskla River, about 300 kilometers east-southeast of today's Ukrainian capital Kiev and about 100 kilometers south of today's Russian border. The gunpowder had become unusable in the winter and there was also a lack of usable ammunition for the cannons. As a result, the Swedes could not bomb the fortress and the siege dragged on. The garrison of the fortress had a strength of 4,200 soldiers under the command of Colonel Alexei Stepanovich Kelin. These were supported by the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the armed population (2,600 men in total). During the following 87 days of siege they managed to repel the Swedish attacks. This gave Peter enough time to muster his own superior military forces to relieve the fortress.

Peter was in dire straits before the battle: he had to divide his strength and attention between the Swedish threat in the west and that of the uprising in the whole south and south-west. Its appearance on the main theater of war was delayed by another illness, which dragged on from the end of April to the beginning of June 1709. Finally, the Russian armed forces with a total of 42,500 men in 58 infantry battalions and 17 cavalry regiments as well as 102 guns arrived at the end of May on the opposite side of the Vorskla river. The Russian command took hold at the following council of war on 16./27. June the decision to fight the Swedes. On the same day, the Russian vanguard crossed the river north of the city of Poltava near the village of Petrowka, thus ensuring the passage of the main group of their army, which took place on June 20/1. July took place. Tsar Peter the Great camped near the village of Semyonovka . On June 25th / 6th In July the Russian army shifted south and took their camp five kilometers from Poltava. The Swedes were trapped. They could no longer withdraw without a battle. Nevertheless, Karl hesitated and that gave Peter the chance to build a fortification for his troops, on which the Swedish army could crush itself. In front of the camp there was a kilometer-wide open space with dry sandy soil. This land bordered the Budyshenesky Forest. The Jakowtzy Forest, a green area with streams and water channels, was 100 meters south of the camp. June 26th / 7th In July the Russians began to fortify the front line. They built ten entrenchments between these woods to defend the camp. Each redoubt consisted of a high earth wall with a trench in front of it. The redoutes were manned by 4,000 infantry soldiers (eight battalions) and had 16 guns. New elements in linear tactics that were first used here were the erection of redoubts in front of the actual line of defense. Behind this line were 17 cavalry regiments under the command of Menshikov . Ataman Ivan Skoropadskyj had positioned his Cossacks behind the Ivanchinsti brook.

During a reconnaissance mission, Charles XII. Seriously injured for the first time during his many campaigns: A Russian rifle bullet hit him on the back of the heel on the left foot and kicked out again on the big toe. Several bones were splintered. Karl is said to have continued his inspection ride anyway; when he arrived at headquarters, however, he passed out from his horse. In the next few days the wound became infected and the king was in mortal danger. After he had recovered somewhat, he ordered the attack in order to forestall further Russian defensive measures and to throw the Russians back onto the river. This had become necessary when the Swedish found out that the Russians would be on June 29th / 10th. July new reinforcements expected. The supply situation for the Swedish army, on the other hand, was critical. It continued to lack ammunition and powder for artillery and infantry. Of the 32 available Swedish guns, only four were therefore operational and many infantry muskets could not be used. With no help in sight, attack was the only way out. Karl handed over the command to Field Marshal Rehnskiöld and General Lewenhaupt, to whom 20,000 soldiers were made available for the battle. The issuing of orders, however, remained unclear and caused confusion and confusion between the individual units in the further course of the battle. About 2,000 Carolinians and some Zaporozhian Cossacks Masepas stayed in the camp near Poltava.

The battle

The Swedes' plan was for the army to greg during the night of July 8th . to take a position in the south of the Russian entrenchments and overpower the Redouten before dawn. The infantry troops led by Lewenhaupt were to be the first to pass the Redoutenlinie ; after them the cavalry should come. The infantry soldiers were then to attack the Russian fortified camp. However, the Swedes did not know how strong these field fortifications were, nor that the Tsar had just expected such a surprise attack and had taken his precautions. The Swedes fell into a trap and responded with their attack on the tactical-strategic guidelines of Peter, who consistently dictated the battlefield for the Swedes. The 18 Swedish battalions were divided into four columns, supported by a battery with four cannons. The Swedish infantry took their position shortly after midnight. Their position was about a kilometer south of the first Russian redoubt, where the sounds of saws and hammers could be heard. When the cavalry followed two hours later, it was already getting dark. This delay of the Swedish troops undermined the surprise element of the operation. After consulting his most important generals, the king decided to carry out the attack anyway.

At around two o'clock in the morning, the Swedish army attacked the Russian fortified camp near the village of Jakowzy with its four columns and six cavalry columns in the dark. Due to the delays in the formation of troops, this attack did not surprise the Russians. After two hours of fighting, the Swedes only managed to take two shelters. The attack on the third redoubt was repulsed.

Rehnskiöld now made a regrouping of the Swedish troops. At the same time he was now trying to bypass the Russian fortifications. Menshikov tried to prevent this with his cavalry and had initial successes: 14 Swedish standards and flags had been captured. However, the tsar ordered this attack to be stopped. He had recognized that Menshikov would not crush the forces in front of him even with reinforcements. The Russian dragoons retreated north, pursued by both wings of the Swedish cavalry. Karl rated the withdrawal as a success and believed in an imminent victory. When the Swedes bypassed the line of closed Russian entrenchments, they were caught in heavy artillery and rifle fire. In doing so, they lost a quarter of the infantry and a sixth of the cavalry and were forced to seek cover against the targeted artillery fire in the forest of Maly-Budyschensky. The Swedish battalion, led by the Swedish generals von Schlippenbach and Roos , was not informed of the regrouping and evasion of the redoubts and was therefore separated from the rest of the Swedish troops. When a column of about 4,000 Russian supply troops occupied the fortified positions again, General Roos and his soldiers were trapped.

At about six in the morning Peter I led his army out of the camp and made them line up in two lines. In the center he placed the infantry under Anikita Ivanovich Repnin , on the right flank the cavalry of Menshikov and on the left General Rodion Christianowitsch Baur . The artillery commanded Lieutenant General Jacob Bruce . Marshal Sheremetev received the supreme command in this battle . As a colonel, Peter commanded only one infantry division. A reserve of nine infantry battalions remained in the camp. By nine o'clock the formation of the main Russian army with a strength of 32,000 men and 70 cannons was completed. Because of their numerical superiority, the Russian front was 400 to 500 meters wider than that of the Swedes. In addition, the Swedes' flanks were not sufficiently secured.

Rehnskiöld let the Swedes compete against the Russians. The king was also on the battlefield; he was lying on a stretcher carried by guards. At nine o'clock in the morning, Charles XII. the signal to attack. He initially attacked the left flank of the Russian army. Here the experienced Novgorod regiment disguised itself as recruits and thus formed a supposedly easy target for the Swedes. Supported by cannon and musket fire, the Swedish battalions stormed forward in a violent bayonet attack and shook the front Russian lines. But the success was short-lived. Peter himself led the counterattack at the head of the second battalion, his hat being shot through with a shotgun. Around eleven o'clock the Swedish forces weakened. The Russian artillery was particularly effective, while Karl attacked his infantry without artillery support, exposing them to Russian fire without any protection. While the right wing of the Swedish army was being pushed back by the Russian artillery, the Russian cavalry overwhelmed the left flank of the Swedes under Roos, which was separated from the main Swedish army. With over 1,000 dead and little ammunition, General Roos was forced to retreat south. His troops sought refuge in the forest north of Poltava, where they were crushed by Menshikov's cavalry. After the Swedish troops under Schlippenbach and Roos had surrendered, the Menshikov cavalry penetrated the rear and flank of the main Swedish army. The Swedish cavalry tried in vain to buy time for the infantry. The Swedes were no match for the Russian superiority and began the retreat, which turned into a real escape. Under the unstoppable rush of Russian infantry and cavalry, the Swedes panicked and fled in chaotic confusion.

The bearers of Charles XII. fell in the Russian fire, the stretcher broke and the king escaped from the battlefield only at the last moment with a heavily bleeding wound, accompanied by Masepa. Voltaire passed on in his biography of Charles XII. on the escape of the Swedish king:

"Charles XII. did not want to flee, he could not defend himself. Only Colonel Poniatowski ... was still with him ... He signaled two followers, they took the king under the shoulders and lifted him onto a horse, despite the excruciating pain. Now Poniatowski, who had no command in the army, obeyed the need to become the leader. He gathered 500 mounted men around the person of the king ... The sight of their king gave the small group new strength. She made her way through more than ten Russian regiments with naked weapons and got to the Swedish entourage. The king's horse was killed on this ride, hounded on all sides. Colonel Gierta, himself badly wounded, gave him his. "

On the evening of the battle, Peter held a banquet. Raising his trophy in honor of the captured Swedish generals, he thanked them as his masters in the field of warfare .

losses

There is little uncertainty about the Russian losses in the Battle of Poltava. They totaled 1,345 dead and 3,290 wounded. On the other hand, there is different information about the Swedish losses. Drygalski speaks of four captured artillery pieces, 139 captured flags, 2,795 prisoners, and 9,234 dead and wounded. Robert Massie gives more details: 6,901 dead and wounded (including 300 officers), and 2,760 prisoners (including 260 officers). Among the prisoners were Prince Max von Württemberg, Supreme Commanding Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld, Prime Minister Count Carl Piper as well as four major generals (Baron Carl Gustav von Roos, Wolmar Anton von Schlippenbach etc.) and five colonels. Other authors keep their statements more general and put the Swedish casualties in the battle at around 10,000 men.

Surrender of the Swedish troops

After the battle, the returning Swedes gathered in the camp near Pushkarivka. Overall, the army with the troops that were still in front of Poltava and at the various river crossings consisted of around 15,000 men (mostly cavalry) and 6,000 Cossacks. The only line of retreat was the route to the south, which led into the Crimean Tatar area . Under their protection, Charles XII hoped to be able to reorganize and refresh his troops before they would be returned to Poland through Ottoman territory. On the afternoon of the day of the battle, the army marched south along the Worskla. On her march she passed three fords across the river without using them, as she already believed she was being followed by the Russian associations and therefore did not want to stop. On July 10, the army arrived at Perevolochna at the confluence of the Vorerskla and Dnepr rivers and found that there were no bridges or fords there. Also, the few boats were not enough to evacuate the entire Swedish army.

It was therefore decided at the Swedish headquarters that Charles XII, the wounded and an escort from Sweden and Cossacks should cross the Dnieper and move through the steppe to the southern Bug on Ottoman territory. The army, on the other hand, was supposed to march up the Worskla again and, after crossing the river, turn south at a ford to the Crimea. From there it was to rejoin the king in Ochakov on the Black Sea . On the night of June 30th, Jul. / July 11, 1709 greg. the king crossed the river with Ivan Masepa, his companion Kost Hordijenko as well as 900 Swedes and 2,000 Cossacks. The army, now under the command of General Lewenhaupt, prepared to leave for the following morning. At 8 o'clock, however, a Russian column of 6,000 dragoons and 3,000 Kalmyks under General Menshikov arrived.

In view of the demoralization and disintegration phenomena that were becoming evident everywhere, as well as the current shortage of food and war material, Lewenhaupt considered a renewed armed conflict to be hopeless and immediately initiated negotiations, in the course of which Menshikov imposed normal conditions of surrender. Only the Cossacks would not be treated as prisoners of war, but as traitors. Levenhaupt consulted with the remaining generals and colonels and it was finally agreed to surrender, although numerically they were almost doubly superior to the opposing Russian troops. On the morning of June 30th, Jul. / July 11th Greg. at 11 a.m. the Swedish army surrendered with around 14,000 soldiers, 34 guns and 264 flags. Most of the remaining Cossacks fled on their horses to avoid punishment as traitors. The column of King Charles XII. reached the Southern Bug a few days later on July 17, where she was held for two days until the Pasha von Ochakov gave his permission to enter the Ottoman Empire . A rearguard of 600 men was no longer able to cross the bow; she was overtaken and cut down by 6,000 Russian horsemen under General Volkonsky.

Consequences of the battle

The glory of victory led contemporary military professionals to carefully study the experience of this battle. The main Swedish army was completely destroyed and Charles XII. was incapacitated for the next six years in exile in the Ottoman Empire. With the defeat of Charles, in a few hours he lost the reputation that he had gained in Europe with his victories. The reports of victory reached all crowned heads in Europe by courier. For the European public, the news from the Poltava battlefield was news that initially aroused incredulous amazement. From then on, power and prestige in Europe passed from Karl to Peter. Russia now appeared as a great power of the future and emerged as a serious opponent of all European powers.

For Sweden, the defeat meant the complete collapse of Charles XII's strategic concept of eliminating Sweden's opponents one after another by applying superior warfare. This marked a turning point in the war. Nevertheless, on the day after the battle, Sweden remained the dominant great power in Northern Europe with a predominance in the Baltic region. Peter used the advantage he had gained and immediately after the battle ordered the Swedish Baltic provinces to be conquered. At the same time, the triple alliance between Russia, Denmark and Saxony-Poland was restored. From then on, Russia and its allies Denmark-Norway and Saxony had the strategic initiative and began to penetrate Swedish territory further or again - later together with their new allies Prussia and Braunschweig-Lüneburg .

The celebrations that the Tsar organized across Russia corresponded to the magnitude of the victory. The triumphal procession, which was held in Moscow on December 21, 1709, provided a memorable spectacle. Under the thunder of the guns from the walls of the city and the ringing of the church bells, the marching column set in motion, accompanied by the clang of trumpets and the bang, with Russian guards regiments marching ahead with the captured trophies, flags and standards, then the captured Swedish officers followed in ascending order to Field Marshal and Prime Minister, all on foot. The evening closed with large fireworks.

Remembrance and commemoration

In Sweden the memory of the battle is cultivated in a peaceful, objective and tourist way. In Russia and Ukraine, the memory of Poltava is a political issue. Lomonosov depicted the tsar in the midst of the tumult of battle in a famous large glass mosaic (6.44 meters × 4.81 meters). Even Pushkin celebrated the victory over Sweden in a poem and condemns the betrayal Masepas. For the 100th anniversary of the battle in 1809, a monumental victory column was erected on the Round Square in Poltava . Shortly before, the place had received the status of a governorate town, which brought it basic architectural features appropriate to this rank: public and private buildings in the classical style, parks, ring roads.

The 200th anniversary of the victory - after the defeat in the war against Japan and the turmoil of the revolution of 1905 - was celebrated with particular lavishness. Tsar Nicholas II appeared at the memorial sites to honor the dead and to inaugurate numerous memorials, including the White Rotunda, a viewing platform at the point where the old fortress had been. In the same year a museum on the history of the battle was donated, today Tsar Peter stands in front of it in full size. The 250th anniversary, which fell during the thaw under Khrushchev , was also celebrated with gun salutes and fireworks. Monographs, festive events, anthologies and essays completed the memory of the 250th anniversary of 1959.

Poltava has been on the territory of independent Ukraine since 1991, which now has its own national idea and its own self-image. While Russia, as the victor of the battle, believes that it is the liberator of Ukraine, Ukrainian historiography comes to a different conclusion: the Ukrainian Cossacks were oppressed by the tsarist empire. During the Great Northern War, the army of Peter I used scorched earth tactics in Ukraine . As a sign of protest, the hetman Iwan Masepa and parts of his Cossacks went over to the Swedes. Peter, enraged by this betrayal, razed the Cossack residence, Baturyn , with women and children. From the Ukrainian point of view, the 300th anniversary should be an occasion to present the battle as a testimony to the political and military alliance between Ukraine and Sweden: for a 300-year special relationship between the Hetman Masepa and Karl XII. have donated; some national Ukrainian exegetes trace this alliance back to Norman times. The Swedish reactions were not unfriendly, but restrained. The 2009 celebrations were dominated by a Masepa renaissance, which has become a central figure of Ukrainian national consciousness. The hetman's likeness has been featured on 10 hryvnia banknotes for years .

- “Like a Swede at Poltava” is still a phrase in Russian and Ukrainian that indicates a person's absolute helplessness.

- The Battle of Poltava was so significant that a modern Russian coin (in platinum) was dedicated to it.

- A stamp pad was issued on June 26, 2009 to mark the 300th anniversary of the Battle of Poltava in Russia. It shows the painting Tsar Peter I in the Battle of Poltava by Gottfried Danhauer (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

Representation in the film

In the 2007 film Pact of Beasts - The Sovereign's Servant (Russian Слуга государев ), director Oleg Ryaskov staged the events of the battle.

literature

- Klaus-Jürgen Bremm : In the shadow of disaster - Twelve decisive battles in the history of Europe. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2003, ISBN 3-8334-0458-2 .

- Peter Englund : The Battle That Shook Europe - Poltava and the Birth of the Russian Empire. Tauris Publishing, London 2002, ISBN 1-86064-847-9 .

- AD from Drygalski: Poltava. In: Bernhard von Poten : Concise dictionary of the entire military sciences. Volume 8, Leipzig 1879.

- Robert K. Massie : Peter the Great - His Life and Time. Fischer, Frankfurt / Main 1987, ISBN 3-596-25632-1 .

- Geoffrey Regan: Battles that Changed History. 2nd edition, Carlton Publishing Group, London 2002, ISBN 0-233-05051-5 .

- Benjamin Richter: Scorched Earth - Peter the Great and Karl XII. The tragedy of the first Russian campaign. MatrixMedia Verlag, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-932313-37-0 .

- François Marie Arouet de Voltaire: History of Charles XII, King of Sweden. German Book Association, Hamburg / Stuttgart 1963.

- Виктор Калашников: Атлас войн и сраженйи. Белыи Город, Москва 2007, ISBN 978-5-7793-1183-0 ( German: Viktor Kalašnikov: Atlas of wars and battles ).

Web links

- Battle of Poltava

- Dietrich Geyer: Turning point - It started in Poltava. In: Die Zeit No. 23 May 28, 2009, accessed on July 24, 2009 .

- Baron Berndt Otto I. von Stackelberg

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c A. D. von Drygalski: Poltava. P. 7.

- ^ Peter Englund: Poltava. Stockholm: Atlantis, Stockholm 1988, ISBN 91-7486-050-X , pp. 280-281.

- ↑ a b A. D. von Drygalski: Poltava. P. 7; Виктор Калашников: Атлас войн и сраженйи. Москва 2007, p. 151; Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His Life and Time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 453.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1992, p. 184.

- ↑ Bengt Liljegren | Liljegren, Bengt - Karl XII: En biografi, Historiska media, 2000, Sidan 151.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1992, p. 183.

- ↑ Valentin Giterman: History of Russia. Second volume. Frankfurt am Main, 1965, p. 92.

- ↑ Erich Donnert: Peter the Great. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1988, p. 72.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1992, p. 185.

- ↑ Erich Donnert: Peter the Great. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1988, p. 74.

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. P. 120.

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. P. 115.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1992, p. 184.

- ↑ Valentin Giterman: History of Russia. Second volume. Frankfurt am Main, 1965, p. 93.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20141203154615/http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/die-geschichte-karls-xii-konigs-von-schweden-2435/5 Project Gutenberg; François Marie Arouet de Voltaire: The story of Charles XII, King of Sweden. 1748, chapter 5.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 453.

- ^ For example: Geoffrey Regan: Battles that changed History. London 2002, p. 128.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 456.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 458 f.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 460.

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. P. 121.

- ↑ Erich Donnert: Peter the Great. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1988, p. 77.

- ↑ http://www.zeit.de/2009/23/A-Poltawa/komplettansicht , The time : turning point - It began in Poltava, Dietrich Geyer , edition of May 27, 2009, no.23.