Northern War (1674–1679)

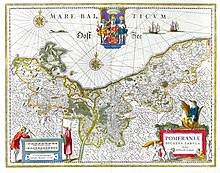

The Northern War from 1674 to 1679 , also known as the Swedish-Brandenburg War or the Scandinavian War , was an independent partial conflict between Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark on the one hand and the Kingdom of Sweden on the other in the parallel Dutch War . Sweden was an ally of France, while Austria, Brandenburg-Prussia, Denmark and Spain fought on the side of the Netherlands across Europe. The war was divided into several large phases. In the first, the Brandenburg army repulsed a Swedish invasion of the Kurmark . In subsequent campaigns by the victorious Brandenburgers, Danes and their allies, after protracted fighting until 1678, they conquered the Swedish properties in northern Germany, Swedish Pomerania and Bremen-Verden . Denmark was also involved in the Skåne theater of war from June 1676 and bore the brunt of the naval war against Sweden in the Baltic Sea. A Swedes invasion of East Prussia in the winter of 1678/79 was successfully repulsed by the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm .

The war between Brandenburg and Sweden ended on June 29, 1679 with the Peace of Saint-Germain . Denmark and Sweden signed the Treaty of Lund on September 26, 1679 . Contrary to the victorious course of the war for Brandenburg-Prussia, it was only awarded a small part of its conquests due to the power constellation at European level. Between Denmark and Sweden, the pre-war acquis was restored.

Differentiation between the Swedish-Brandenburg War and the Scandinavian War

In the nationally influenced historical research of the 19th century, there was no uniform overall representation of this conflict. This is how the view of two separate conflicts arose in literature. In Denmark and Sweden the term Skåne War became common, in Prussia and Germany this war was called the Swedish-Brandenburg War.

A clear separation of the military actions between the two partial conflicts is not possible, however. Denmark and Brandenburg-Prussia already had contractual relations with each other before the outbreak of war in 1674. In addition, both states coordinated their operations at the beginning of the war. During the course of the war there was also temporal overlap between the theaters of war in Skåne , in the Baltic Sea , in Swedish-Pomerania , Bremen-Verden and in the Duchy of Prussia . The two allies finally made peace with Sweden only a few weeks apart.

prehistory

War of devolution

The Second Swedish-Polish War (1655–1661, also known as the Second Northern War ) had exhausted Sweden for the time being. Thus Louis XIV , the ruler of France, saw the opportunity to begin the realization of his dream of French hegemony over Europe. Under the flimsy pretext of an alleged right of inheritance - “devolution” - he attacked the Spanish Netherlands in 1667 and triggered the war of devolution . However, he met the determined resistance of the Protestant Netherlands ( States General ), England and Sweden. In the Peace of Aachen in 1668 , France had to surrender most of its booty.

Louis XIV then began to plan a campaign of revenge against the Protestant Netherlands, his former allies, which had been prepared with many diplomatic negotiations. He blamed them mainly for the formation of the Triple Alliance , under whose pressure the French conquest could be brought to a standstill.

The Habsburgs viewed this development with mixed feelings. On the one hand, the rulers in Vienna dreamed of the " extirpation of the heretics", i.e. the Protestant Dutch, on the other hand the House of Habsburg could not possibly tolerate a strengthening of French power.

In Berlin in 1670 the French envoy unsuccessfully sought the alliance or at least the neutrality of Brandenburg-Prussia. Brandenburg-Prussia under Elector Friedrich Wilhelm I concluded the alliance treaty of Potsdam with Wilhelm von Oranien , the governor of the Netherlands, on May 16, 1672 , with which the Brandenburgers undertook to provide 20,000 auxiliary troops for the Netherlands against payment of subsidies.

Outbreak of the Dutch War

Immediately afterwards, in June 1672, Louis XIV attacked the States General, triggered the Dutch War and in a short time advanced until shortly before Amsterdam . In August 1672, the elector moved with the agreed 20,000 men to Halberstadt in order to be able to unite with imperial troops there . The presence of this troop power alone was enough for Louis XIV to withdraw Marshal Turenne and 40,000 men from Holland and relocate them to Westphalia . Without a decisive meeting, the elector concluded the separate peace of Vossem on June 16, 1673 , with which he gave up the Dutch alliance. In return, France vacated the occupied Duchy of Kleve and paid for the outstanding payment of subsidies by Holland. In the event of a war against the Holy Roman Empire, the treaty did not prevent the elector from fulfilling his duty as imperial prince and from opposing France again.

Also in 1673, Brandenburg-Prussia and Sweden formed a protective alliance that was valid for 10 years. Both sides, however, reserved a free choice of alliance in the event of a war. Due to the protective alliance with Sweden, the elector did not expect Sweden to enter the war on the part of France. Since Sweden was also a member of the Reich due to its northern German possessions, it was supposed to join the general Reich decision or at least remain neutral in the war against France that broke out in the summer of 1674. In the summer of 1674 Marshal Turenne devastated the Electoral Palatinate according to plan , forcing the Reichstag to declare France an enemy of the Reich.

On August 23, therefore, a 20,000-strong Brandenburg army marched to Strasbourg , where Turenne's army had meanwhile been maneuvered by the imperial general Raimondo Montecuccoli . At the beginning of October, the Brandenburg army crossed the Rhine and a few days later united with the imperial army near Strasbourg.

By sending the Brandenburg army to the Rhine, the French under Marshal Turenne were only able to hold out against the numerically superior army of the Allies on this section. Although the French under Marshal Turenne won the battle of Türkheim on December 26, 1674 over the imperial and Brandenburgers, the losses suffered so high that the imperial army was able to withdraw unhindered to its winter quarters. The Brandenburgers took winter quarters in the Schweinfurt area . It was therefore of essential importance for France to relieve her army on this section.

Formation of the Franco-Swedish alliance

In the meantime French diplomacy had succeeded in persuading the traditional allied Sweden, who had only been saved from the loss of all of Pomerania in the peace of Oliva through French support, to enter the war.

The basis for this was a subsidy agreement concluded with France in April 1672 , which promised to provide 400,000 riksdalers a year if Sweden undertook to maintain 16,000 soldiers in Swedish Pomerania . In the event of war, this sum should be increased to 600,000 riksdalers. The French government thus obtained the assistance of Sweden in the war against the Republic of the United Netherlands. At the time, Sweden had great difficulty in defending its great power status in view of a deficit national budget and was therefore dependent on French support payments. In addition, the country was weakened domestically, since after the death of King Charles X. Gustav in 1660, a Regency Council under Chancellor Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie (1622–1686) took over the business of government, since the heir to the throne Charles XI. (1655–1697) had not yet reached the age of majority at this time. Within the council, Finance Minister Gustav Bonde (1620–1667) pushed through radical cuts in the budget for the navy, army and fortress construction.

For Sweden, in view of the intended war of aggression, it was of paramount importance to keep peace with Denmark in order to be able to use all resources against the highly likely opponents Brandenburg, the Habsburg Monarchy and the Dutch.

Therefore, at the end of 1674, Count Nils Brahe (1633–1699) was sent to Copenhagen to strengthen the friendly relations. Denmark was initially neutral. The Danes' hesitation was explained by the fact that Denmark and Sweden fought two wars for Skåne between 1643 and 1661, both of which ended with Denmark's defeat. After the so-called Torstensson War , it ceded Jämtland , Härjedalen , Gotland and Saaremaa to Sweden in the Treaty of Brömsebro (1645) . During the Northern War , in the Peace of Roskilde (1658), it also lost Schonen , Blekinge and Halland ( Skåneland ). These losses were not finally accepted in the Danish government. Added to this were the extensive disputes between Denmark and Sweden over the Gottorf shares in the duchies of Holstein and especially Schleswig , which became even more explosive through the marriage of Charles X Gustav to Hedwig Eleanora of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf. The Danish government sought allies in the 1660s and formed defensive alliances with the Republic of the United Netherlands and Brandenburg-Prussia .

When the success failed to materialize, the Swedish side toyed with the idea that Wrangel's army should turn against the Danish Holstein first . The Swedish Chancellor and Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel endorsed this plan, but the French ambassador opposed it.

The Swedes then gathered an army in Swedish Pomerania. Prince Johann Georg von Anhalt , governor of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, worried about the troop assemblies, asked the Swedish Commander-in-Chief Carl Gustav Wrangel about the intention of the Swedish deployment via the Brandenburg Colonel Mikrander . Wrangel, however, failed to respond and declined a further request to speak from the Prince of Anhalt.

First phase of the war: Operations in Northern Germany

Swedish invasion of the Mark Brandenburg

painting by Matthäus Merian Junior, 1662

Although Sweden had declared itself binding to invade the countries of the Holy Roman Empire in November, the invasion was delayed by a month at the instigation of the Swedish Chancellor. The French ambassador would have preferred to see an invasion of the imperial (Austrian) hereditary lands , but this was considered impracticable.

The hostilities finally began on December 25, 1674, when the Swedish army, between 13,700 and 16,000 men and 30 guns, advanced into the Uckermark via Pasewalk without a declaration of war . Under the orders of Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, they set up their headquarters in Prenzlau and initially remained passive. Only in February did it advance again and occupy the Uckermark, Prignitz , Neumark and Hinterpommern except for Lauenburg and a few smaller towns. The few Brandenburg troops withdrew to the fortified places along the Havellinie. Then the Swedish army went to its winter quarters.

In May 1675 the Swedes began a spring campaign with the aim of crossing the Elbe in order to protect themselves. a. to unite with the 13,000-strong troops of the allied Duke Johann Friedrich von Braunschweig-Lüneburg and then to operate in the rear of the imperial and Brandenburg armies on the Rhine front, thereby relieving the French forces. Although the state of the Swedish army at that time was no longer the same as it had been in earlier times, and suffered from unclear leadership and a lack of discipline, it was still surrounded by its former reputation. This led to rapid initial success for the Swedes, who occupied large parts of the market in a short time. Wrangel moved his headquarters to Havelberg and made preparations for the planned crossing over the Elbe. The Swedish occupation was marked by severe rioting, violence and looting against the civilian population. Some contemporary chronicles reported that these excesses were worse in scale and brutality than in the time of the Thirty Years' War .

In June the Netherlands and Spain declared war at the urging of the Elector Sweden. Otherwise Brandenburg received no support from the Reich and Denmark. Elector Friedrich Wilhelm now decided to drive the Swedes out of the march with the remaining Brandenburg troops in an independently led campaign. The Brandenburgers left their camp on the Main at the beginning of June 1675 and reached Magdeburg on June 21. Within only a week they succeeded in driving the Swedes back to Swedish-Pomerania in a chase that was becoming ever faster and more chaotic, with significant losses. The battle of Fehrbellin , in which the Swedes suffered a heavy defeat, was of particular importance in these battles . This caused a sensation all over Europe. The Brandenburg army, which had never gone into battle alone before, had beaten the excellent Swedish troops out of the field. The Brandenburg Army then moved into neutral Mecklenburg and took up quarters there.

Political upheaval in Sweden

The defeat meant revolutionary changes for Sweden. The government business previously led by the Chancellor went to King Charles XI. about who picked up new armor. Militarily, the defeat for Sweden meant that the previously only latent hostility of various European powers now became more apparent and one had to reckon with further declarations of war and thus an expansion of the war on the Swedish side. It was now also evident on what fragile basis the Swedish war plans were based. Although Fehrbellin's defeat was not a devastating one, the time of great plans for Sweden was over. So from now on one concentrated on the defense of the empire. The sluggish administration, which often only followed the royal orders with great delays, turned out to be a hindrance to armament. The equipment of the fleet and army was therefore constantly behind the requirements. Sweden's further hopes now rested on its fleet, and great armaments efforts were concentrated on it. The Swedish plans stipulated that after a victory over the Danish fleet, which was considered likely, the own fleet should go to the Oresund near Copenhagen , prevent the Dutch fleet from penetrating the Baltic Sea and bring up the enemy's merchant ships, in order to take back the Danes to force their war power out of the German territories. After that, King Charles XI. land on Zealand with troops from Skåne and Carl Gustav Wrangel from Swedish Pomerania .

Expansion of the war

Encouraged by the victory of the Brandenburgers in the Battle of Fehrbellin, on July 17, 1675, the Habsburg Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire declared Sweden an enemy and thus the Imperial War and determined with the Mandata Avocatoria that all subjects of the Holy Roman Empire should renounce any service in Sweden had. The Westphalian Imperial Circle and the Upper Saxon Imperial Circle were tasked with fighting the Swedes. The Swedish envoy in Vienna was expelled. At the end of July, a 5,300-strong imperial contingent under Field Marshal Lieutenant Count Coop joined the Brandenburgers in Mecklenburg. The Duke of Hanover declared his neutrality due to the circumstances. Bishop Christoph Bernhard von Galen von Münster and Duke Johann Friedrich von Lüneburg have now also declared themselves ready to take part in the fight against the Swedes.

Denmark also joined the alliance at the end of July. At a Brandenburg-Danish conference on July 27, 1675 with General Gustav Adolf von Baudissin on the Danish side, a joint military approach between Brandenburg and Denmark was decided. Sweden was now isolated in the fight against Brandenburg, other states of the Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, the Netherlands and Spain.

Autumn campaign in Pomerania

Denmark was preparing for the beginning of the war and had a field army of 30 regiments of cavalry and infantry , a total of 20,000 men. The fleet was also put into combat readiness. Their strength was 42 warships, the smallest armed with 30, the largest with 80 cannons.

In preparation for the march, the Danes occupied and secured all passes in Holstein up to Hamburg . In addition, the Danish king ordered the Kattegat to be closed with a Danish and a Dutch warship . The first acts of war between Danes and Swedes took place on August 22, 1675, when two Danish ships, coming from Glückstadt , with 80 men manned, attacked the Swedish ski jump Braunshausen near Stade . During this brief skirmish, one of the two Danish ships with 40 men was sunk (21 dead, 19 prisoners). The other then withdrew.

The Danish King Christian V now ordered Field Marshal Adam von Weyher to collect the invading army near Oldesloe (Holstein). The Danish fleet, reinforced by Dutch warships, received the order on August 22nd to move to the Baltic Sea in order to cross off the coast of Swedish Pomerania. On September 2, 1675, Denmark declared war on Sweden. The Danish king set out from Copenhagen on September 3rd for Oldesloe, where he arrived on September 9th for the display of his now assembled army . This army had a strength of 18,000 men and 40 field guns and was under the command of General Field Marshal Weyher. The advance of the approximately 16,000 strong Danes through northern Mecklenburg began on 12/22. September. The intention was to reach Swedish-Pomerania via Gadebusch near Rostock through the neutral Mecklenburg. The aim of the Danes was to support the Brandenburgers and at the same time to secure Danish interests in the region. The Danish king exerted great influence on the issuing of orders throughout the entire campaign.

On September 20th the Danes reached Wismar . On September 21st, the king explored the area around the city and enclosed the city with two regiments of cuirassiers and one regiment of dragons. Then the Danish army moved on. They reached Doberan on September 25th . King Christian V and the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm I met here on September 25, 1675, decided on an offensive alliance and agreed on common war goals. For Denmark, this consisted in regaining the provinces lost in the peace treaties of 1645 and 1660, as well as Wismar and the island of Rügen . Brandenburg was to receive all of Swedish Pomerania for this.

Rosenborg tapestries 1684–1693

On September 29th the Danes marched through Rostock, on September 1st and 11th. In October they reached Damgarten , the first place in Swedish Pomerania. There was the Swedish Field Marshal Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck with some troops. The Danes built a bridge as a crossing over the Recknitz , the border river, and lost 25 men due to the heavy Swedish counterfire. Because of the extensive mud along the way, it was not possible to bypass the Swedish hill on the opposite bank. Up until October 16, both sides were involved in a positional battle here.

While the Allies were advancing into Pomerania, nothing went well on the Swedish side. The planned departure of the fleet had to be postponed again and again due to failures in arming the fleet. The fleet did not go to sea until October 9th. On the 16th the fleet got into the open sea and had almost reached Gotland when it got caught in a heavy storm. Since a large part of the crews became seasick, the fleet management decided to return to Dalarö , where they arrived on the 20th. The war plans of King Charles XI. were thus thwarted and the loss of the German provinces certain. The reasons for the failed operation lay in the poor management of the fleet. The crew and equipment of the ships were incomplete. This went hand in hand with a lack of discipline and a poor level of training among the teams.

The Swedish king, realizing the full extent of the grievances after this failed operation, decided to take the reins of the government into his own hands. The influence of the Imperial Councilors and the Imperial Chancellor dwindled to a minimum. King Charles XI. then went from Stockholm to Bohuslän , which was attacked from Norway. Field Marshal Rutger von Ascheberg tried to organize a defense there. On November 4th, Charles XI. Vanersborg .

The leadership of the Swedish troops in Pomerania by Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel became increasingly negligent. He himself went to Stralsund and from there to the island of Ruden to await the arrival of the fleet, and left Field Marshal Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck and Field Marshal Conrad Mardefelt to defend Swedish Pomerania. The Brandenburg Elector had already started moving again on September 9th, after his army had moved into Mecklenburg at the end of June and had remained there ever since. The Brandenburgers quickly succeeded in advancing to the Peene near Gützkow on October 15, 1675. Field Marshal Mardefelt left his position near Wolgast before the elector had even started the attack. This opened the way to Pomerania for the Brandenburgers and Danes.

After the breakthrough of the Peene line, the Swedes evacuated on 16./26. the passes between Damgarten and Tribsees on the Mecklenburg border and withdrew to the remaining fortified places. The Danes pursued the Swedes as far as Stralsund. The Danes and Brandenburgers could not agree on a siege of the city, however, because the campaign season was too far advanced.

So the Danes concentrated on the siege of Wismar . The city was of great importance to the Swedes as it was the only good port on the German coast and was within reach of Denmark. King Christian V reached the besieged city on October 26th. On October 28, there was an unsuccessful assault on the city. After the siege ring got close enough, fire mortars shot into the city from November 1st. The port of Wismar was blocked by a drawn chain. On December 13th, the city fell into the hands of the Danes.

The Brandenburgers occupied the island of Wollin from October 10th to 13th and besieged Wolgast from October 31st . Wolgast, violently attacked by a 3500 men and eight cannons strong Brandenburg contingent, surrendered on November 10, 1675.

At the end of 1675, the Swedes only held their ground in Demmin , Anklam , Greifswald, Stralsund and on the island of Rügen, except in Stettin . From then on, the war in Pomerania turned into a protracted fortress war that would drag on for several years. With this result, all activities ended for the time being, as the rough weather that set in early, the lack of food and illnesses forced the elector to release his troops into the winter quarters in mid-November. At the beginning of 1676, Swedish forces tried to recapture Wolgast , which was held by Brandenburg with six companies (a total of 300 men) under Colonel Heinrich Hallard called Elliot . With 1,500 men, the Swedes made an unsuccessful assault on the enclosed city on January 15, 1676. The Swedish losses amounted to 120 dead and 260 wounded.

Allied campaign against Bremen-Verden

The second larger Swedish possession in northern Germany, next to Swedish Pomerania , was the Duchy of Bremen-Verden . For reasons of power politics and in order not to offer the Swedes any opportunity for advertising and recruiting, the Allies decided to conquer these two duchies. The neighboring imperial principalities of Münster and the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg also joined Denmark and Brandenburg-Prussia as allies .

The campaign began on September 15, 1675 with the advance of the Allies into the two Swedish duchies. One Swedish fortress after another was quickly conquered. The Swedes were troubled by the high number of mostly German deserters who were forbidden to use weapons against states of the Holy Roman Empire after the imperial ban was imposed.

By the end of the year, only the Swedish capital Stade and Carlsburg were in Swedish hands. From November the Allies released their troops into the winter quarters, so that the conquest of the last remaining Swedish places dragged on well into the next year. Stade did not capitulate until August 13, 1676. However, this theater of war remained of secondary importance for the Allies and the Swedes.

Second phase of the war: expansion of the fighting

At the beginning of the 1676 campaign season, Sweden was on the defensive on land. Except for the besieged Stade, the northern German possession of Bremen-Verden was completely in the hands of the Allies. Swedish control in Swedish Pomerania was limited to Rügen and a few fortified places.

In 1676 the fighting widened again in terms of geography and intensity. New land fighting areas were opened in Skåne and the Swedish provinces bordering Norway. In addition, a heavy sea war raged on the Baltic Sea. The highest intensity of the fighting took place in the most important theater of war in Skåne, followed by the final fighting in Swedish Pomerania. The fighting, which often took place at the same time, dragged on in all theaters of war with mixed results until the end of 1678.

Skåne and the Baltic Sea

1676

Swedish offensive plans

Sweden prepared for attack and defense for the new year. A planned attack on Norway in winter had to be suspended, however, as the rivers did not form a load-bearing layer of ice due to the mild weather.

The defense had to cover many points. Skåne was threatened. The level of defense there was poor; so the fortresses were in poor condition. Troops and provisions were brought to Gotland. King Charles XI. ordered the return of Field Marshal Wrangel from Swedish Pomerania, said goodbye to Mardefelt and gave Field Marshal Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck supreme command on November 27, 1675. The fleet remained the main means of maintaining Sweden's scattered possessions. Only through them could one strengthen the much melted land troops in Germany, protect Gotland, repel attacks on Scania, and hold on to the prospect of carrying the war into enemy territory.

On April 29th, the Swedish Baltic fleet ran out again with 29 ships of the line and 9 frigates. It was supposed to transfer grain and infantry to Pomerania and, in return for the fortress war, bring cavalry from there that were no longer needed. The purpose was primarily an attack on the Danish islands, for which King Charles XI. wanted to participate from Skåne. To do this he went to Skåne. His troops gathered in Östra Karup . On May 22nd he was in Malmö with the troops, ready to land on Zealand. Charles XI. now just waiting for his fleet.

Danish sea and land offensives

The total strength of the Danish army grew through army reinforcements in the course of the year to 34,000 men, including the garrisons . The commander in chief of the land forces was Johann Adolf von Holstein-Plön . After the operations in northern Germany were largely completed, the former Danish province of Skåne and the island of Gotland were now to be conquered. In support of the Danish army in Skåne, the Norwegian governor Ulrik Fredrik Gyldenløve was to attack southwards from Norway to Gothenburg .

Gotland was to be captured by the Danish admiral Niels Juel's fleet at the beginning of the campaign . In order to keep this goal secret for as long as possible, he first headed for Rügen before heading for Gotland. Upon arrival, the fleet landed 2,000 men. The landed troops and the Danish fleet then attacked the island's capital Visby from the land and sea side. Visby capitulated on May 1, 1676. After the entire island was under Danish control, Admiral Juel took possession of the fortified city of Ystad on the south coast of Skåne.

On May 25, 1676 at hit Bornholm the Swedish Baltic Sea fleet, which outnumbered with 60 ships to which only recently united Danish-Dutch fleet. However, no decisive battle developed, so that after a short battle the Swedish fleet withdrew northwards, mainly because the Swedes hoped to have an advantage in the expected decisive battle if it took place near their own coast.

After the Dutch and Danish fleets had merged, on May 27, 1676, the Danish fleet command was transferred from Admiral Juel, who only held the office in the meantime, to the Dutch Admiral Cornelis Tromp . After the end of the sea battle at Bornholm , the Allies went in search of the Swedish Baltic Sea fleet, which was located on June 1st near Öland . The allied fleet consisted of 25 ships of the line (10 of them Dutch) and 10 frigates . The Swedish Baltic fleet was slightly superior with 27 ships of the line and 11 frigates. In the subsequent naval battle near Öland , the Allied fleet was able to achieve an important victory. The Swedes lost four ships of the line, three smaller frigates and over 4,000 men dead. In contrast, the Allied losses were insignificant.

As a result of the victory, the Danes and Dutch gained naval control in the southern Baltic Sea. The Danish king used this advantage and let the Danish main army of 14,000 men go ashore on June 29, 1676 in Skåne between Råå and Helsingborg . The excellently planned amphibious operation proceeded without incident or resistance. Under the impression of the Danish landing in Skåne, large parts of the rural population of Skåne and Belkinge began to rise up against the Swedish rule, which was perceived as foreign rule. This resulted in a bloody guerrilla war known as the Snapphanar War. The northern Schonischen free rifle corps and partisan units, the so-called Snapphanar (Danish: Snaphaner ), from then on formed a constant threat to the Swedish supply lines. The Swedish king tried to master this movement with draconian punishments. On April 19, 1678, for example, he issued the order to burn down all the farms in the parish of Örkened and to execute all men who could carry a gun (all men between 15 and 60 years of age).

In this distressed situation the Swedish army withdrew from Skåne and Blekingen north to Växjö . Before that, the Swedes strengthened the fortified places Malmö , Helsingborg , Landskrona and Kristianstad . On August 2nd, the Danes took Landskrona on their advance. This was followed on August 15 by the storming and capture of Kristianstad. At the same time, the Danish fleet conquered the small towns of Kristianopel and Karlshamn on the south-east coast of Sweden. One month after the landing, only fortified Malmö remained in Swedish hands.

Parallel to the advance of the main Danish army, an army detachment under General Jakob Duncan with about 4,000 men was sent north in early August to conquer Halmstad and then to advance further north to join the troops of General Gyldenløves, who was marching on Gothenburg . On August 11th, Charles XI sat down. moving west with a small army to stop the Danish advance. Both armies met on August 17th. In the following battle near Halmstad , the Danish division was defeated, thus ending the Danish attempt to advance further north from Skåne and establish contact with Gyldenløve's Norwegian troops. The Swedish troops were still too weak for a direct confrontation in Skåne, so they retreated north to Varberg to await reinforcements. The day after the battle, Christian V marched from his camp near Kristianstad and headed towards Halmstad. On September 5th he reached the place and began an unsuccessful siege.

The Danish-Norwegian army under Gyldenløve, numbering around 8–9,000 men , had marched from Norway along the coast towards Gothenburg on June 8th (July) . The Swedes for their part only had about 1,400 men to muster at the time. Gyldenløve subsequently devastated Uddevalla and Vänersborg , but came to a halt at Bohus Fortress .

Danish setbacks

Despite the tense situation for Sweden, the resistance was maintained. In August France declared war on Denmark. Since King Christian did not accept the advice of the experienced Johann Adolf von Holstein-Plön, who wanted to carry out further operations against the Swedes, the entire army remained inactive until they entered their winter quarters in the area between Helsingborg and Ängelholm . The Norwegian army also withdrew to Norway to move into winter quarters. In this situation, Johann Adolf returned his command, as he found the situation unbearable. Due to the large number of interference in his command by courtiers and by the king himself, he was not able to command independently. Christian personally took command of the army and did not appoint a new commander in chief that year.

Since the Danes continued to wait and see, the Swedes took the initiative. On October 24, 1676, King Charles XI marched. entered Skåne with an army of 12,000 men and, contrary to all expectations, attacked the Danish winter quarters near Lund on December 4, 1676 . In the resulting Battle of Lund, the Swedes won one of the bloodiest battles in Scandinavian history (50% dead on both sides). The fortunes of war turned in favor of the Swedes, who despite the severe winter, encouraged by the victory, initiated the reconquest of the provinces of Skåne and Blekinge. Some Swedish regiments advanced to Helsingborg, which surrendered to the Swedes on January 11, 1677. Immediately afterwards the Swedish army marched on Christianopel , which was also conquered after a short resistance. The Swedes then conquered Karlshamn after a four-day siege. At the end of the campaign year, the Danes finally only controlled the Christianstadt fortress , while the remainder of the main Danish army had withdrawn to Zealand .

1677

Sea war in the Baltic Sea

The situation for Denmark at the beginning of 1677 was not very good. The fight in Skåne could only continue if the supply over the Øresund could continue to be ensured. Since after the declaration of war by France on the Danish side a dispatch of a French fleet was feared, Admiral Tromp was sent to the Netherlands to advertise a further Dutch fleet reinforcement. The Swedes 'goal was to cut off the Danes' supply lines to Skåne. This required the unification of the previously two-part Swedish fleet. At the end of May, the Gothenburg squadron set sail to join the main Swedish fleet in the Baltic Sea. Since Tromp was still in the Netherlands, Juel was commissioned to stop the Swedish naval advance with the Danish fleet.

Coming from the Great Belt , the Swedish Gothenburg squadron met the Danish fleet commanded by Juel south of Gedser near the island of Falster . The Danes with their nine ships of the line and two frigates were clearly superior to the seven ships of the line of the Swedes. The sea battle at Møn , which took place on June 1, 1677, was again won by Denmark. Five ships of the line with 1,500 prisoners including the Swedish admiral Erik Carlsson Sjöblad were lost to the Danes. Juel's victory was of great strategic importance as the Swedish naval power continued to melt and the danger of the supply routes being interrupted was averted.

After this victory, Juel retired to the position between Stevns on Zealand and Falsterbo on the Swedish coast in order to prepare for the decisive battle with the Swedish Baltic fleet. On June 21st he received the news that the Swedish Baltic fleet had been put to sea and sighted near Bornholm . The Swedish fleet under Admiral Henrik Horn headed for the Danish fleet, which remained in position to join the expected Dutch relief fleet under Admiral Tromp. The Swedish fleet had 48 ships of the line and frigates as well as six fire brigades . Their goal was to isolate the Danish fleet from their naval base so that they could no longer cover the supply lines. Niels Juel had 38 ships and three fires. The first contact between the two fleets took place on July 1, 1677. Although the Dutch fleet under Admiral Tromp had not yet arrived, Juel accepted the battle. The sea battle in the Køgebucht went back in favor of the Danes. Four ships were seriously damaged by them, but they did not suffer any total loss. The Swedes, however, lost 10 ships of the line and frigates (7 of which were captured), three fires and 9 smaller ships. In addition to the 1,500 dead and wounded, 3,000 Swedes were taken prisoner. In contrast, the Danes lost only 350 dead and wounded. As a result of the Danish victories that year, the Allied fleet maintained control of the maritime domination. No other major actions took place this year.

Campaign in Skåne

In the spring of 1677 the Danish army had recovered from its losses from the previous year. Soon she controlled a large part of Scena again. In the unoccupied areas, a violent and ruthless guerrilla war raged by the local Skåne population against the Swedes.

In May, 12,000 Danes were landed at Landskrona and forced the Swedish forces of around 3,000 men, after a brief encounter, to break off the siege of Christianstadt. Baron Joachim Rüdiger von der Goltz was appointed the new commander-in-chief of the Danish army .

After Christianstadt was relieved, the Danish army reached Malmö on June 19 (greg.). The strategically important city under the command of the Swedish Lieutenant General Fabian von Fersen (1626–1677), however, offered bitter resistance. The Swedes repulsed an assault on the city on the night of June 25th to 26th (July) with heavy losses on the Danish side. The siege was then abandoned and the Danish army withdrew towards Landskrona.

There the two kings met again on July 14, 1677 (greg.) In the battle of Landskrona . The Danish king commanded the left wing of his army, the right was led by Lieutenant General Friedrich von Arensdorff . When the Swedes under King Charles XI. attacked the right wing massively and this dissolved into disorder, the left Danish wing also withdrew. The Swedes remained victorious again. The Danes went back to Landskrona, where they were besieged by the Swedes.

Attacks from Norway on Jämtland

The Norwegian viceroy Gyldenløve attacked again from Norway in the same year and had several successes. On July 28th (greg.), After a two-hour battle, he took the town of Marstrand and conquered the fortress Carlsten , which had previously been considered impregnable . With the possession of these important forts, Gyldenløve controlled the provinces of Bohuslän and Jämtland . The Swedish Chancellor Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie now marched to Bohus with an army of 11,000 men, according to Danish information. The 3,000-strong Norwegian-Danish troops there under General Löwenhielm attacked the Swedish army in heavy rain and won a victory. According to Danish information, the Swedes are said to have lost 1,000 men in this process.

In the autumn, Viceroy Gyldenløve had to retreat to Norway again when he was harassed by stronger Swedish forces. Thus, the campaign year 1677 ended in the same way as that of 1676.

1678

From summer 1677 to summer 1678, the war focused primarily on the town of Kristianstad , which was still held by the Danes and only surrendered after a long siege in August 1678, as well as on the driving back of the Danish-Norwegian troops from the western Swedish provinces.

The Danish army was distributed as follows in 1678: On Scania there were 11,165 Danes, 6036 men from Münster's auxiliary troops and 1,300 men from Hesse's auxiliary troops under Colonel Johann ufm Keller . The garrison strength was 9281 men. 2488 men were on duty in the fleet. There were 10,000 men in Norway. The crew in the Duchy of Bremen was 3000 men strong. Together this was a force of 43,270 men. Of these, 9,000 were cavalry . The artillery consisted of 500 men with 40 field pieces. All in all, despite all the setbacks, it was still a powerful army.

In order to relieve the besieged Christianstadt, the Danish King Christian V set out for Skåne on March 23, 1678 in order to gather a relief army from Landskrona, but this failed. The Danish garrison under Major General von der Osten, which had melted down to 1,400 men, had to capitulate after a four-month siege due to their poor supply situation.

Pomerania and Prussia

1676-1678

The united Danish-Dutch fleet, allied with Brandenburg, succeeded on June 11, 1676 in defeating the Swedish fleet on the southern tip of Öland . This meant that the Swedish troops in Pomerania could no longer receive any supplies or support from the mother country. The later Brandenburg cuirassier regiment No. 4 succeeded in conquering the Peenemünder Schanze on July 13, 1676 . This had secured the passage through the Peene . Anklam was conquered on August 29, 1676 and Demmin fortress on October 20, 1676 .

At the end of October 1676 the Brandenburgers were able to start enclosing Szczecin due to their previous victories. The city was well supplied, so a siege would be protracted. The Swedish city commandant Major General Wulffen had a force of 4,125 men at his disposal; 800 of them were Germans. When winter began, the elector had the siege postponed and the soldiers sent to winter quarters. The subsequent deployment of troops and heavy artillery dragged on until June 1677, when the siege ring around the city was complete. The fight lasted six months. The besiegers bombed the city with heavy artillery and destroyed most of the buildings. On December 22, 1677, Wulffen gave up the now hopeless defense.

In the meantime, in September 1677, Rügen was occupied by the Danes, who, however, lost their General Detlef von Rumohr in the Battle of Warksow in January 1678 , were defeated by the Swedes and driven back from Rügen.

Campaign in Pomerania 1678

The campaign in Pomerania in 1678 was only opened in August with the attack on Rügen by Brandenburg troops in the south and a Danish troop contingent in the north of the island. The possession of the island by the Allies was a basic requirement for a conquest of the Swedish fortress Stralsund . Troops could have reached Stralsund from the Swedish mainland via Rügen without the Allies being able to prevent this. The invasion carried out on September 22nd with 9,000 men brought the final conquest of the island for the Allies by September 24th. A large number of the Swedish crew of only about 2,700 were captured, the rest of them fled to Stralsund via Altefähr .

On October 5th, the Brandenburgers stood in front of Stralsund and began to siege the city . After the arrival of the troops from Pomerania, they had over 21,500 men and 80 guns. The resistance here was nowhere near as great as in Stettin. After a bombardment on October 20, 1678, the city surrendered to the Brandenburg army on October 25. The remaining 2,543 Swedish soldiers were allowed to leave the city with full military honors and embark for Sweden. After the capture of Stralsund, the Brandenburg army advanced in front of the also heavily fortified Greifswald , which 14 days later, on November 7th, was the last city to be captured by the Swedes. The Swedish occupation was allowed to withdraw and the city was occupied by Brandenburg troops. This meant that all of Swedish Pomerania was in Brandenburg hands.

by Bernhard Rode around 1783

Winter campaign 1678/79 in East Prussia

In the Duchy of Prussia only weak forces were during the war, were unable impending Swedish invasion of Livonia fend off. Sweden wanted to invade Poland-Lithuania on its side in order to conquer East Prussia for itself. The Polish King Johann Sobieski had made considerations in this direction, but could not, due to the demands of Poland-Lithuania in the Turkish war, free forces to participate.

In October 1678, the Swedish army set up in Livonia under Field Marshal Henrik Horn , around 12,000 men strong, began the advance to Courland. On November 15, she crossed the Prussian border north of Memel . Resistance was low, so the Swedes advanced without any problems. However, even after the peace treaty with the Ottomans, Poland-Lithuania stayed away from an alliance with Sweden when it became known that Stralsund had surrendered to the Brandenburgers. With the capture of Stralsund, the original purpose of the Swedish enterprise, the relief of Swedish Pomerania, became obsolete. The Swedes were now faced with the risk of being confronted with the Brandenburg army, which had now become free. Due to this changed strategic situation, the Swedes stopped their advance to Königsberg . The Swedish field marshal received orders to move into winter quarters in Prussia and to remain passive.

Elector Friedrich Wilhelm set out from Berlin in mid-December with an army of 9,000 men and 30 guns in the direction of Prussia. On January 20, the Brandenburg relief crossed the Vistula and reached Marienwerder , the first assembly point for the infantry. The elector prepared the famous Great Sleigh Ride from here . In a letter to the governor and the city council, he gave orders to provide 1,100 sleds and 600–700 horses for his army . In addition, he gave the order to the cavalry troops under General Görzke standing in Königsberg to pursue the fleeing Swedes immediately. After they had received the news of the arrival of the elector, they withdrew to Livonia and reached Tilsit on January 29, 1679 . The Brandenburg cavalry tried to catch up with the Swedes as ordered.

The infantry continued their advance, now on sleds, from Marienwerder to Heiligenbeil . From there, a seven-mile train took us across the Fresh Haff to Koenigsberg on January 26th. The troops continued the sleigh ride to Labiau on January 27th . On January 29, she reached the village of Gilge at the mouth of the Memel in an express march across the frozen Curonian Lagoon . Without waiting for the arrival of the main army, a Brandenburg advance command consisting of 1,000 cavalry men under Colonel Joachim Henniges von Treffenfeld attacked a number of Swedish regiments housed near Tilsit on January 30 and dispersed them. In the battle near Tilsit, the Swedes lost several hundred men dead and wounded.

The next day, the Brandenburg cavalry under Görzke and the Treffenfeld promoted to major general for his victory the day before attacked the retreating Swedes again. In the battle at Splitter 1,000 Swedes were killed, 300 captured and five cannons captured. When the Swedes continued their retreat through Lithuanian territory, the elector had the persecution stopped on February 2nd, as the lack of supplies, cold and illness also made itself felt among his troops. They then moved into accommodation in Prussia. The elector only sent the Swedes a small contingent of 1,500 cavalry under Major General Hans Adam von Schöning , who fought with the Swedish rearguard at Telschi in Lower Lithuania (Shamaites) on February 7th . This contingent stopped their pursuit eight miles from Riga ( Schöning maneuver ) and began their march back to Memel on February 12th.

As a result, the Swedes under Field Marshal Horn brought only 1,000 horsemen and 500 infantrymen back to Swedish territory in Livonia from his formerly 12-16,000 men . This winter campaign of 1678/79 went down in history as The Hunt over the Curonian Lagoon .

Third phase of the war: War with France (1679 until peace)

On August 10, 1678, the Netherlands and France concluded a separate peace that ended the parallel Dutch War. In the peace negotiations taking place in Nijmegen since 1676 , both parties decided to return all Dutch territories in full. France, which had started the war to conquer the Netherlands, wanted instead to take harm from the Dutch allies. Prince Wilhelm did not want this peace, but had to give in to the republican and commercial interests of the Dutch.

When the winter campaign had just ended, on February 5, 1679, Emperor Leopold I ended the war between the empire and France and Sweden in the Peace of Nijmegen . According to this treaty, Brandenburg was to return its conquests to Sweden. Brandenburg-Prussia now faced France alone. The French policy stipulated that any change in the territorial regulations of the Peace of Westphalia was ruled out from the outset in order not to create a prejudice against France's annexations in Alsace and Lorraine . Apart from that, France could not and would not tolerate Sweden's disadvantages in a war to which it had been instigated by France. Since the elector stubbornly refused to surrender the conquered territories, Louis XIV ordered an 8,000-strong corps under Lieutenant General Baron de Calvo to march into Cleve , which belongs to Brandenburg , and pillage the country.

At the end of May 1679, after an armistice between Brandenburg and France had expired, a 30,000-strong French army moved into the county of Mark . The Brandenburg forces in the western provinces at the time amounted to 8,000 men and were led by Lieutenant General Alexander von Spaen . Spaen had his cavalry set up at the Porta Westfalica in order to block it. After a heated battle with the French overwhelming forces, however, the Brandenburgers were thrown back to Minden on June 21 . Soon after, on July 9, 1679, the war ended with the Peace of Saint-Germain .

Peace treaty and consequences

In the Peace of Saint-Germain, Friedrich Wilhelm was ordered to return all territories conquered in Swedish Pomerania to Sweden by the end of the year. Sweden was obliged to implement the border treaty of 1653, according to which it should renounce the strip of land on the right bank of the Oder, with the exception of Damm and Gollnow , in favor of Brandenburg. Sweden waived the levying of Seezöllen Oder estuary, and France promised 300,000 Reichstaler of Brandenburg to pay. The French evacuated the occupied Brandenburg provinces of Cleve and the county of Mark by the end of February 1680.

Denmark, the ally of Brandenburg, also had to lay down its arms without having achieved its goal of regaining Skåne and the other Scandinavian provinces that King Charles X Gustav had wrested from him.

As a result of this peace agreement, Swedish Pomerania remained under Swedish rule until the Great Northern War . Brandenburg-Prussia, which was previously of little importance, gained a considerable amount of reputation through the military victories over the invincible Swedish troops. However, the elector had not achieved his goal of permanently winning West Pomerania, including the Oder estuary, which is so important for Brandenburg .

Through skillful diplomacy and political pressure, the French had succeeded in avoiding Sweden's excessive concessions.

In Berlin, people felt they were being treated unfairly and left in the lurch by the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I , his ally. The elector argued that the emperor had claimed his vassal loyalty in the Imperial War against France and thereby embroiled him in the war with Sweden, but then left him in the lurch when he came along without the elector's knowledge and without any regard for the interests of Brandenburg France made peace. The emperor, in turn, wanted to prevent a strong Protestant principality from developing in the north of the empire and accepted disadvantages for the empire in return.

This led to a change in the Brandenburg alliance policy, away from Habsburg and towards France. In the peace treaty of Saint-Germain, France and Brandenburg agreed to work together in a secret section. In October 1679, the elector signed a secret agreement with France, which obliged him to vote for Louis XIV at the next election. In January 1681, Brandenburg entered into a defensive alliance with France.

See also

literature

- Hans Branig : History of Pomerania Part II: From 1648 to the end of the 18th century , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-09796-9 .

- Dietmar Lucht: Pomerania - history, culture and science up to the beginning of the Second World War , Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1996. ISBN 3-8046-8817-9

- Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army - From the 15th Century to 1914 , Vol. 1, Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1967, Page 229-271. ISBN 3-7648-0414-9

- Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. - Elector of Brandenburg, Queen Prussia , Heinrich Hugendubel Verlag, Kreuzlingen / Munich 2004. ISBN 3-424-01319-6

- Friedrich Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm, the great Elector, and his time: A history of the Prussian state during the duration of his government , Verlag von Gustav Hempel , Berlin 1855.

- Paul Douglas Lockhart: Sweden in the seventeenth century , 2004 by Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-73156-5

- Maren Lorenz : The wheel of violence. Military and civil population in northern Germany after the Thirty Years War (1650–1700) , Böhlau: Cologne 2007. ISBN 978-3-412-11606-4

- Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II von Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693) - A political biography , Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin 1998. ISBN 3-428-09497-2

- Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , Fourth volume, Gotha 1855. ISBN 978-3-86195-701-0

- Samuel Buchholz : Attempt a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , fourth part: new history, Berlin 1767.

- Frank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675 - Brandenburg-Prussia's rise to a great power , Potsdam 1998. ISBN 3-921655-86-2

- Anonymous: Theatrum Europaeum , Vol. 11, Frankfurt / Main 1682.

- Michael Fredholm of Essen: Charles XI's War. The Scanian War Between Sweden and Denmark, 1675-1679 (= The Century of the Soldier 1618-1721, Volume 40). Helion & Company, Warwick 2019, ISBN 978-1-911628-00-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , Part Four: New History, Berlin 1767, page 88

- ^ A b Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , fourth part: new history, Berlin 1767, page 89

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 597

- ^ A b Robert I. Frost: The Northern Wars - War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558-1721 , London / New York 2000, p. 209

- ^ Robert I. Frost: The Northern Wars - War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558-1721 , London / New York 2000, pp. 208f

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 598

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 599

- ↑ Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , fourth part: new history, Berlin 1767, page 92

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 600

- ↑ The strength of 16,000 men, which corresponds to the contractual agreements between France and Sweden of 1672, is u. a. given in: Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , Part Four: New History, page 92

- ↑ Michael Rohrschneider, page 253

- ↑ Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg, fourth part: new history, page 92

- ↑ Barbara Beuys: The Great Elector - The Man Who Created Prussia , Reinbek bei Hamburg 1984, p. 347

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 609

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , P. 621

- ^ Karl Friedrich Pauli : General Prussian State History , p. 171.

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , p. 625

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , P. 627

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , P. 629

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. , P. 635

- ↑ PDF at www.northernwars.com ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Jack Sweetman: The Great Admirals - Command at Sea, 1587-1945 , 1997, ISBN 0-87021-229-X , p. 118

- ^ Jack Sweetman: The Great Admirals - Command at Sea, 1587-1945 , p. 119

- ^ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680., p. 64

- ↑ Jack Sweetman: The Great Admirals - Command at Sea, 1587-1945 , p. 121

- ^ Jack Sweetman: The Great Admirals - Command at Sea, 1587-1945 , p. 122

- Jump up ↑ Jack Sweetman: The Great Admirals - Command at Sea, 1587-1945 , p. 125

- ^ Eduard Maria Oettinger: History of the Danish Court, Third Volume, Hamburg 1857, p. 140

- ^ Eduard Maria Oettinger: History of the Danish Court, Third Volume, Hamburg 1857, p. 144

- ^ Eduard Maria Oettinger: History of the Danish Court, Third Volume, Hamburg 1857, p. 145

- ^ Eduard Maria Oettinger: History of the Danish Court , Third Volume, Hamburg 1857, p. 147

- ^ Eduard Maria Oettinger: History of the Danish Court , Third Volume, Hamburg 1857, p. 149

- ↑ Hans Branig: History of Pomerania, Part II: From 1648 to the end of the 18th century , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, page 28

- ↑ Dr. Fr. Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm the great Elector and his time , Verlag von Gustav Hempel, Berlin 1855, page 149

- ^ Fr. Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm the great Elector and his time , Verlag von Gustav Hempel, Berlin 1855, page 151

- ^ A b Fr. Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm the great Elector and his time , Verlag von Gustav Hempel, Berlin 1855, p. 151

- ^ Karl von Rotteck: General history from the beginning of historical knowledge up to our times , eighth volume, Freiburg im Breisgau 1833, second chapter, page 59

- ↑ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I - Elector of Brandenburg, King in Prussia , Heinrich Hugendubel Verlag, Kreuzlingen / Munich 2004, p. 26.