Prenzlau

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 53 ° 19 ′ N , 13 ° 52 ′ E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Brandenburg | |

| County : | Uckermark | |

| Height : | 30 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 142.96 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 18,970 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 133 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 17291 | |

| Primaries : | 03984, 039851 (permanent) | |

| License plate : | UM, ANG, PZ, SDT, TP | |

| Community key : | 12 0 73 452 | |

| City structure: | 8 districts | |

City administration address : |

Am Steintor 4 17291 Prenzlau |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Hendrik Sommer ( independent ) | |

| Location of the district town of Prenzlau in the district of Uckermark | ||

Prenzlau ( Low German Prentzlow ) is the district town and the administrative seat of the northern Brandenburg district of Uckermark , one of the medium-sized centers in Brandenburg . Prenzlau is the historic capital of the Uckermark landscape and, in the Middle Ages , was one of the four largest cities in the Mark Brandenburg along with Berlin-Cölln , Frankfurt (Oder) and Stendal .

Origin and spelling of the place name

The place name is of Slavic origin and means "settlement of a man named Premyslaw" . Between the 15th and the end of the 19th century there is evidence of both the spelling Prentzlau / Prenzlau and Prentzlow / Prenzlow .

geography

The city is located about 100 km north of Berlin and 50 km west of Szczecin ( Poland ). In Prenzlau, the Ucker river leaves the Unteruckersee (the largest of the numerous Uckermark lakes ) on its way north towards the Baltic Sea into the Stettiner Haff . The urban area borders the “Uckermärkische Seen” nature reserve in the southwest, and the two largest lakes in the Uckermark adjoin the city of Prenzlau in the south: the Unteruckersee and the Oberuckersee in the Schorfheide-Chorin biosphere reserve.

City structure

According to its main statute, the following districts belong to the city of Prenzlau:

-

Alexanderhof (with the living spaces Bündigershof and Ewaldshof)

First documented mention in 1840; officially confirmed in 1843. - Blindow

first mentioned in a document in Daniel de Blingowe in 1269. Already proven in 1298 as a place Blingow . For the years 1337 with Blingowe and 1375 with Blyngow there are further documented mentions. From 1786 onwards the spelling Blindow continued . - Duration

-

Dedelow (with the residential areas Ellingen and Steinfurth )

First mentioned in a document as in Dedelow in 1320. - Güstow (with the Mühlhof residential area)

- Klinkow (with the Basedow residential area )

- Schönwerder

- Seelübbe (with the residential areas Augustenfelde, Dreyershof and Magnushof)

first mentioned in 1262 in a document from Pope Urban IV, who confirmed the annual interest of 1 hoof in the village of Seelübbe (Scelube) to the Prenzlau nunnery .

as well as the living spaces

- Stegemannshof

- Wollenthin.

The formerly independent communities of Dedelow, Klinkow, Güstow, Schönwerder, Dauer and Blindow have belonged to the city of Prenzlau since November 1, 2001.

history

Until the 19th century

Archaeological finds show that today's urban area has been inhabited since the younger Stone Age. After increasing settlement activities by Slavic tribes could be observed from the 7th century, the area developed into a central settlement and castle complex in the 10th to 13th centuries. In the 10th to 12th centuries there was a late Slavic rampart west of the Ucker ("Röwenburg"). A late Slavic settlement (in the area of today's Sabinenkirche) emerged as a forerunner of the Pomeranian city foundation. In the first half of the 12th century, another late Slavic / early German settlement emerged in the area of the later Franciscan monastery.

Towards the end of the 12th century, the Dukes of Pomerania called numerous Low German settlers into the area as part of the high medieval state development in Germania Slavica , who established new independent settlements.

Prenzlau was first mentioned in 1187 by a priest Stephan in Prenzlau (Stephanus sacerdos Prinzlauiensis) as a documentary witness. In 1188 it was described as Prenczlau as a castle town with a market and a jug (castrum cum foro et taberna) . A church and one of the three mints in Pomerania (with Stettin and Demmin ) also belonged to this place . In 1188, Prenzlau was an important long-distance trading center with a central local function, which in 1234 was elevated to a free city (civitas libera) under German law, the most modern city law at the time, by Duke Barnim I (Pomerania) . The town charter contained a novelty, the double seal of Duke Barnim I - above an older one and below the seal from the exhibition period. There is currently no explanation for this unusual appearance of two seals from the same exhibitor.

The central town, which was granted city rights in 1234, had grown together from three settlement centers. The oldest Slavic settlement core was west of the Ucker around the St. Sabine Church. To the east of the Ucker a commercial settlement arose around the church of St. Nicolai and a more agrarian-oriented settlement around St. Jacobi.

At the time of the Landin Treaty in 1250, the city of Prenzlau already had four parish churches and a monastery (Magdalene), including the Marienkirche as the first hall church in East Elbe . With seven churches from the High Middle Ages, Prenzlau was the most richly endowed community of the Mark with churches after the twin and cathedral cities of Brandenburg.

Soon after 1234, before 1250, the city was completely fenced , presumably, as was customary at that time, with ramparts, palisades and moats. All of the Brandenburg cities received stone city walls in the second half of the 13th century at the earliest. B. Prenzlau 1287. The city got water mills and a field mark of 300 Hufen , the largest rural equipment in a city between the Elbe and Oder.

The Magdalenenkloster was also built before 1250 , presumably as a donation from a member of the Pomeranian ruling house. The Reform Order, popular in the Altreich at that time, was created in the 1220s to offer prostitutes who were not allowed to marry the opportunity to escape from the brothel to the monastery. Although women from the bourgeoisie and the nobility also entered Magdalenenkloster, the choice of this order should be an indication of the “metropolitan” character of Prenzlau among the Pomeranian dukes.

The primacy established under the Pomeranian dukes meant that Prenzlau never lost its membership in the top group of cities in the Mark Brandenburg (with Berlin / Cölln , Brandenburg, Frankfurt (Oder) and Stendal ). The inclusion in the trading area of the Hanseatic League , without any evidence of Prenzlaus membership , was particularly beneficial. According to the land book of Emperor Karl IV. In 1377 [!] Prenzlau and Stendal had to pay a land amount of 500 marks each in silver. The twin cities of Brandenburg followed a long way behind with 300 pounds of silver. The Ascanians successfully continued the development policy of the Pomeranian dukes.

After the Ascanian Margraves of Brandenburg died out in 1320, the sovereign balance of power changed several times. In the 13./14. In the 19th century Prenzlau experienced its heyday. In 1426 the city came under Brandenburg rule again under the Hohenzollern family.

Prenzlau suffered a lot from the Thirty Years War and its consequences. The entire region was severely depopulated and economic performance was at a low point. From December 20-22, 1632, the body of the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf was kept in St. Mary's Church . Towards the end of the 17th century, the number of inhabitants increased again due to the influx of Huguenots . These revitalized many branches of industry through the introduction of new production methods. Further measures, such as intensive urban development and the expansion of postal routes as well as a general strengthening of the handicrafts led to an economic recovery in the first half of the 18th century.

The city suffered another setback due to the Seven Years' War . Prenzlau had already been declared a garrison town in the 17th century and military buildings shaped the cityscape more and more. In the Fourth Coalition War , the Prussian General Hohenlohe surrendered near Prenzlau on October 28, 1806 with his remaining 12,000-strong army to the French army . From 1806 to 1812 Prenzlau suffered from French occupation and heavy contributions .

In the middle to the end of the 19th century, some people from Prenzlau emigrated to Australia and founded a new place there called Prenzlau (Queensland) . It is located about 70 km west of Brisbane .

20th and 21st centuries

During the National Socialist era , the synagogue of the large Jewish community built in 1832 was desecrated and destroyed during the November pogrom in 1938 , as were the two Jewish cemeteries at the water tower in today's city park , whose broken tombstones were used as paving stones. The New Jewish Cemetery at Pushkinstrasse 60 was restored after 1945. In the Second World War , Prenzlau lost around 600 people. At the end of April 1945, around 85 percent of the Prenzlau city center was destroyed (inner city 716 of 832, outer city 205 of 1298 properties).

The reconstruction of the destroyed city center began in 1952. Due to the shortage of housing and low economic power in the post-war years, mainly prefabricated buildings , which were popular with the population, were built. In 1974 and 1975 there were individual major fires.

At first the agribusiness was at the center of the economy. Operations such as the sugar factory, the dairy farm, a grain mill and a brewery were important employers. The founding of the Armaturenwerk Prenzlau (AWP) in 1967 created more than 1000 new jobs and the company became the city's largest employer.

After 1990, in the course of German reunification, there were extensive upheavals in all areas. The cityscape was changed by the renovation of numerous buildings and traffic routes, some streets were given new names and former barracks from the Imperial and National Socialist era were converted into administrative or school buildings. Many companies had to close, others reduced their workforce considerably.

Administrative history

From 1817 to 1947 Prenzlau was the district town of the Prenzlau district in the Prussian province of Brandenburg , and from 1947–1952 in the state of Brandenburg . 1952–1990 the Prenzlau district belonged to the GDR district of Neubrandenburg , then again to the state of Brandenburg. Since the district reform in 1993 , Prenzlau has been the administrative seat of the Uckermark district .

Population development

|

|

|

|

|

(from 1991 to December 31st)

Territory of the respective year, population from 2011 based on the 2011 census

The increase in the number of inhabitants in 2001 is due to the incorporation of five previously independent municipalities as a result of the municipal reform.

politics

City Council

The city council of Prenzlau consists of 28 members and the full-time mayor with the following distribution of seats:

| Party / group of voters | Seats |

|---|---|

| CDU | 8th |

| SPD | 6th |

| Independent voter initiative "Wir Prenzlauer" | 5 |

| AfD | 4th |

| The left | 4th |

| FDP | 1 |

(As of: local election on May 26, 2019 )

mayor

- 2001–2009: Hans-Peter Moser ( PDS )

- since 2009: Hendrik Sommer (independent)

Sommer was elected mayor on September 27, 2009 with 54.0% of the valid votes. On September 24, 2017, he was confirmed in office for a further eight years with 84.9% of the valid votes.

coat of arms

The coat of arms that is valid today was approved on July 1, 1997.

Blazon : "Divided by silver and red, on top a gold-armored red eagle with a gold spade helmet put over its head , on it a red flight , below a silver swan floating on blue waves ."

City colors

The colors of the city of Prenzlau are: blue, white, red, as can be found in Julius Ziegler. Easy to understand when looking at the Prenzlauer city arms.

Town twinning

Prenzlau maintains the following international city partnerships :

- Pochwistnewo , Russia (since September 1997)

- Uster , Switzerland (since 2000)

- Varėna , Lithuania (since April 2000)

- Barlinek , Poland (since July 2010)

From 1990 to 2007 there was a town partnership with Emden in Lower Saxony .

Sights and culture

Churches and monasteries

The following churches and monasteries are arranged according to the order in which they were built. With the exception of the Heiliggeistkapelle and the youngest church (Maria Magdalena), they have been used as Protestant parish churches since the Reformation until today.

- The Sabinenkirche (formerly also St. Sabinen, St. Sabini ) is probably the oldest church in Prenzlau because it is located in the area of the Slavic predecessor settlement (Burgstadt) on the left bank of the Ucker. A Magdalen monastery ( 1250–1290) belonged to St. Sabini, and since 1291 a Benedictine monastery (later also called Sabine monastery). The church and monastery were built shortly before 1250, the monastery a little later than the church, which became the monastery church. The church was reformed in 1543 and the monastery was secularized. According to the visitation files from 1543 it was "almost old and dilapidated" . In 1861 it became the property of the city of Prenzlau through several owners. The monastery buildings have completely disappeared today. The structure of the church was changed at the beginning of the 19th century. Since the secularization of the monastery in 1543, it has served as the Protestant parish church of St. Sabinen to this day.

- The old Nikolaikirche ( St. Nicolai ) is the oldest parish church in Prenzlaus on the right of the Ucker. The name Nikolaikirche suggests that it was the church of a merchant settlement. Although the Old Nikolaikirche had already been given up for church purposes before the Thirty Years War , Süring reported a funeral "between the towers" for 1626. After the collapse and later demolition of the nave of the church building, which the people of Prenzlauer proverbially called a “desert church”, only the tower, a western building, now exists . In 1577, the Nikolai patronage was transferred to the church of the former Dominican monastery.

- The Jakobikirche ( St. Jacobi ) was built in the first half of the 13th century, probably as the second oldest parish church on the right bank of the Ucker, as the center of a more agrarian-oriented settlement.

- Marienkirche : originally begun after 1235, three-aisled field stone hall with a nave-wide tower (west building), two-bay nave , transept and retracted choir . Extension 1289–1340 in the brick Gothic style (including the western part of the previous building). Main parish church of Prenzlau (with branches St. Nicolai, St. Jacobi and St. Sabini). Chapels were added in the 14th and 15th centuries; North tower (height: 68 meters) from the 16th century, from 20 to 22 December 1632 the body of King Gustav II Adolf was kept in it; South tower (height: 64 meters) from the 18th century, burned out in 1945, rebuilt after 1970. The late Gothic St. Mary's altar created by the master of the Prenzlauer high altar was saved. This successor building is considered to be the first hall church east of the Elbe. Its splendid eastern façade is “unique in brick Gothic” ( Dehio manual ) because of its sophisticated construction .

- Church of the former Franciscan monastery : The church is called Dreifaltigkeitskirche and was dedicated to St. John the Baptist . It was built as a simple mendicant order church in the middle of the 13th century and completed in 1253, the installation of the vaults took place in the second half of the 14th century. The church was used by the united (Franco-German) community from 1694 until it had to be abandoned in 1774 due to dilapidation. It was not until 1846/1865 that it was restored or rebuilt to such an extent that the Reformed Church could use it again. The Franciscan monastery or " barefoot " was founded between 1240 and 1250; because of the color of the brothers' habit it was called the "Gray Monastery". Between 1536 and 1543 it was secularized and given as a fief to a knight. The buildings were demolished in 1735 without leaving any traces.

- Church of the former Dominican monastery "Zum Heiligen Kreuz": The monastery was founded in 1275 by Margrave Johann II (Brandenburg) and his wife Hedwig von Werle . Construction of the monastery church began in 1275; The church was consecrated in 1343. Because of the color of the Dominican cloak, it was called the "Black Monastery". After the secularization of the monastery in 1544, it was given to the city as a hospital for the poor. In 1577 the monastery church became the parish church of the parish that had become homeless due to the collapse of the Nikolaikirche and was henceforth called St. Nikolai (Nikolairche). Since 2000, the former monastery as a cultural center in its largely preserved buildings has mainly housed the Prenzlau Cultural History Museum ("Dominican Monastery Prenzlau") as well as the city library, the city archive and an event center.

- Heiliggeistkapelle : early 14th century, formerly the chapel of the Heiliggeisthospital, used by the Uckermärkisches Museum from 1899, burnt out in 1945. The chapel has been reconstructed since 2011 and is to be converted into a show brewery.

- Former Georgenkapelle : First mentioned in a document in 1320 as the chapel of the hospital in front of the Schwedter Tor. In the 17th century the chapel was converted into two storeys for residential purposes and has not been used for church since then.

- St. Maria Magdalena ( Catholic Church ): built in 1892 in neo-Gothic style, destroyed in 1945 and rebuilt in 1952.

City wall and towers

With a length of 1,416 meters, almost half of Prenzlau's city wall has been preserved. In the 1990s, the city administration extensively renovated the medieval fortifications and laid out a 3.1 km long circular path. Are preserved

- Rope tower,

- Witch tower,

- Powder tower,

- Schwedt gate tower (also called stone gate tower or simply called observatory due to its use ),

- Mitteltorturm (template for the Oberbaum Bridge in Berlin ),

- Blindow Gate Tower (also Szczecin Gate Tower),

- Wiekhäuser.

Others

- Roland statue on the market square

- Slavic boat Ukrasvan

- Glockenspiel (at the employment office)

- Water tower

- Fire Department Museum of the Age and Honor Department of the Prenzlau Volunteer Fire Department

- Synagogue memorial plate at the water gate (between Wasserforte and Sternberg)

- Memorial plaque in front of the St. Nikolai Church on Diesterwegstrasse to the erased Jewish community and its synagogue

- Memorial stone on the New Jewish Cemetery at Puschkinstrasse 60 in memory of the Jewish victims of fascism

- Cenotaph for the victims of fascism on the Unity Square above the Uckerpromenade

- Several graves of honor in the main cemetery on Friedhofstrasse and Mühlmannstrasse for Nazi victims: 51 Italian prisoners of war (so-called IMIs, later status "civil workers"), 3 Hungarian and 16 Polish combatants and 35 German armed forces deserters , who were publicly released by the SS in April 1945 were shot

- city Park

- Hiking trail on Unteruckersee (at the cape)

Culture

The former Dominican monastery in Prenzlau is now home to the cultural history museum, a picture gallery and the KlosterLadenGalerie . The cultural history museum includes a permanent exhibition on the cultural history of the region, which is supplemented by changing special exhibitions. The picture gallery shows works by the landscape painter Jakob Philipp Hackert . In the KlosterLadenGalerie , pictures by contemporary artists living in the Uckermark are exhibited constantly. Another tradition is the Prenzlauer church music .

In the vicinity of the replica of the Prenzlauer Roland (pedestrian zone on Friedrichstrasse), which was unveiled in 2000, is the “Leda and the Swan” fountain, which establishes a connection between the Prenzlauer heraldic animal and Greek mythology ( Leda ).

In the cemetery of the monastery, the cultural summer is held every year from June to September in the monastery garden , which includes theater performances, concerts and exhibitions.

The ARD transmitter Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg operates a recording studio in Prenzlau, from the regional news for the Uckermark in the program of Antenne Brandenburg are sent.

From April 13th to October 6th, 2013 Prenzlau hosted the state horticultural show .

economy

Resident industries

- Energy industry (based on renewable energies, especially wind energy and the world's first hydrogen hybrid power plant )

- Feed production

- Metal production and processing, mechanical engineering

- Furniture industry (including Prenzlauer Möbelwerke)

- tourism

- Dairy farming ( Uckermark milk )

- Ice cream ( Rosen Eiskrem GmbH )

- Solar industry ( aleo solar AG )

- Housing industry (Wohnbau GmbH Prenzlau)

- Hybrid power plant

On April 21, 2009, Chancellor Merkel laid the foundation stone for the world's first hybrid power plant in the presence of Brandenburg's Prime Minister Platzeck and Economics Minister Junghanns . It was put into operation on October 25, 2011.

- Wind energy

Around Prenzlau there are locations with good wind power suitability , so that the use of wind energy has become an economic factor for the region around Prenzlau and various companies have settled there.

Public facilities

The city is the seat of the district court of Prenzlau .

Infrastructure

traffic

In Prenzlau the federal highway 109 intersects between Templin and Pasewalk and the federal highway 198 between Woldegk and Angermünde . The federal autobahn 11 (junction Gramzow ) and the federal autobahn 20 (junction Prenzlau-Ost and Prenzlau-Süd ) run near the city.

The Prenzlau station, which went into operation in 1863, is located on the long-distance and regional railway line Berlin – Stralsund . It is served by the regional express line RE 3 Stralsund - Berlin - Falkenberg (Elster) and the regional train line Prenzlau - Angermünde . Up until 2000 there was a connection in the direction of Templin ( Löwenberg – Prenzlau railway ). The earlier Prenzlauer Kreisbahnen had four routes with a route network of 108 km. All lines have now been closed (to Klockow 1972, to Fürstenwerder 1978, to Löcknitz 1991, to Strasburg 1995).

The bus transport in the city and in the district is operated by the Uckermärkische Verkehrsgesellschaft .

The Berlin – Usedom long-distance cycle route runs through Prenzlau .

The nearest international airport, Stettin-Goleniów, is 80 km northeast of Prenzlau in Poland.

tourism

Prenzlau has around 30 hotels, guest houses and private rooms as well as the DJH Youth Hostel Prenzlau, European meeting place UcKerWelle (UKW).

At the gates of Prenzlau, 3 km southwest of the Prenzlau city area on the B109, there is the recreational area "Kleine Heide", an 80 hectare mixed forest area.

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Karl Gottlieb Richter (1777–1847)

- Ulrich von Winterfeldt (1823–1908)

- Karl Friedrich August Witt (1832-1910)

- Hermann Dietrich (1856–1930)

sons and daughters of the town

- Lucas Hoffmeister († 1576), son-in-law of the Brandenburg Chancellor Johann Weinlob , from 1552 member of the Court Judge

- Christian Friedrich Struve (1717–1780), professor of medicine in Kiel

- Christian Friedrich Schwan (1733–1815), publisher and bookseller

- Jakob Philipp Hackert (1737–1807), landscape painter

- Friederike Luise von Hessen-Darmstadt (1751–1805), Queen of Prussia

- Ludwig I (Hessen-Darmstadt) (1753-1830), Landgrave

- Amalie von Hessen-Darmstadt (1754–1832), wife of Karl Ludwig von Baden

- Wilhelmine von Hessen-Darmstadt (1755–1776), first wife of the Russian Tsar Paul I.

- Philipp Ludwig Muzel (1756–1831), Protestant theologian, professor at the University of Duisburg

- Georg Friedrich Krause (1768–1836), forest scientist

- Moritz von Bardeleben (1777–1868), Prussian general of the infantry

- Karl Gottlieb Richter (1777–1847), District President in Prussia

- Ernst Ferdinand August (1795–1870), physicist and meteorologist

- Moritz Rathenau (1800–1871), entrepreneur

- Albert von Schlippenbach (1800–1886), poet

- Wilhelm Grabow (1802–1874), politician, President of the Prussian House of Representatives

- Adolf Stahr (1805–1876), writer

- Ludwig von Schlabrendorff (1808–1879), Prussian major general

- Otto Grashof (1812–1876), painter of the Düsseldorf School

- Ernst Schering (1824–1889), pharmacist and entrepreneur

- Emil Mangelsdorf (1839–1925), politician, see list of honorary citizens of Gütersloh

- Johannes Schmidt (1843–1901), linguist

- Albert Stimming (1846–1922), Romanist

- Franz Dibelius (1847–1924), Protestant theologian

- Maximilian Mayer (1856–1939), classical archaeologist

- Max Gerlach (1861–1940), agricultural chemist

- Alfred von Lewinski (1862–1914), major general

- Paul Hirsch (1868–1940), SPD politician

- Emil Karow (1871–1954), Protestant theologian

- Arthur Tetzlaff (1871–1949), publisher

- Gustav Mayer (1871–1948), historian

- Richard Giese (1876–1978), ministerial official in the financial administration

- Kurt Oehlmann (1886–1948), medical officer

- Walter Kaßner (1894–1970), SED politician

- Hans Felix Husadel (1897–1964), composer and conductor

- Lena Ohnesorge (1898–1987), politician (GB / BHE, later CDU)

- Hans-Joachim Denecke (1911–1990), ENT doctor in Heidelberg

- Hans Unger (1915–1975), graphic designer, poster and mosaic artist

- Franz Ehrke (* 1921), SPD politician

- Eberhard Sielmann (1923–2015), table tennis player

- Otto Kaiser (1924–2017), Protestant theologian

- Jürgen Hermann (1927–2018), conductor, musician and arranger

- Joachim Wohlgemuth (1932–1996), writer

- Herman-Hartmut Weyel (* 1933), SPD politician, 1987–1997 Lord Mayor of Mainz

- Christoph Andreas Graf von Schwerin von Schwanenfeld (1933–1996), journalist

- Gerhard Engel (* 1934), historian

- Lonny Neumann (* 1934), writer

- Berthold Hesse (* 1934), Mayor of Prenzlau 1981–1990

- Regine Mönkemeier (* 1938), writer

- Klaus Prüsse (* 1939), handball player

- Gerhild Halfmeier (1942–2020), SPD politician

- Manfred Mäder (1948–1986), killed on the Berlin Wall

- Claus Beling (* 1949), television editor

- Sabine Stüber (* 1953), politician (Die Linke)

- Sabine Engel (* 1954), discus thrower

- Brigitte Rohde (* 1954), track and field athlete

- Carola Zirzow (* 1954), canoeist

- Christiane Wartenberg (* 1956), track and field athlete

- Ruth Leiserowitz (* 1958), historian

- René Bielke (* 1962), ice hockey player

- Peter Schulz Leonhardt (* 1963), draftsman, graphic artist and illustrator

- Matthias Machwerk (* 1968), cabaret artist

- Stefan Zierke (* 1970), SPD politician, Member of the Bundestag

- Josefine Domes (* 1981), musician

- Laura Matzke (* 1988), table tennis player

- Clemens Wenzel (* 1988), rower

- Felix Teichner (* 1991), AfD politician, member of the Brandenburg state parliament

Personalities associated with Prenzlau

- Bernhard Kohlreif (1605–1646), pastor of the Nikolaikirche in Prenzlau

- Wilhelm Pökel (1819–1897), classical philologist , died in Prenzlau

- Henning von Holtzendorff (1853–1919), Grand Admiral of the Imperial Navy , died in Prenzlau

- Joachim von Winterfeldt-Menkin (1865–1945), district administrator of the Prenzlau district, Prussian senior president, state director of the province of Brandenburg

- Silvio Conti (1899–1938), 1934–1938 District Administrator of the Prenzlau district #

- Klaus Raddatz (1914–2002), prehistoric

- Günter Guttmann (1940–2008), 1985–1995 football coach in Prenzlau

- Uwe Schmidt (* 1947), politician (SPD), member of the Brandenburg state parliament since 2014

literature

- Municipality of Blindow (ed.), Lieselott Enders u. a .: Festschrift 725 Blindow. Brochure, undated

- Lieselott Enders: Historical local dictionary for Brandenburg, Part VIII, Uckermark. Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1986, ISBN 3-7400-0042-2 .

- Peter Feist: Medieval city view - Prenzlau. Kai Homilius Verlag , Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-931121-10-0 ( reading sample )

- Sophie Wauer: Brandenburg name book, part 9, The place names of the Uckermark. Verlag Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1996, ISBN 3-7400-1000-2 .

- Olaf Gründel, Jürgen Theil: Prenzlau. Erfurt 2003, ISBN 3-89702-529-9 .

- Jürgen Theil: Prenzlauer Stadtlexikon and history in data. ed. v. Uckermärkischen Geschichtsverein zu Prenzlau, Vol. 7, Prenzlau 2005, ISBN 3-934677-17-7 . ( Online edition )

- Jürgen Theil: Prenzlau from the end of the war to the turning point, Sutton-Verlag 2017, ISBN 978-3-95400-834-6 .

- Jürgen Theil: Alt-Prenzlau. A nostalgic journey through pictures, Sutton-Verlag 2020, ISBN 978-3-96303-071-0 .

- Jürgen Theil, Walter Matznick: Prenzlau 1949–1989, Sutton-Verlag 2008, ISBN 978-3-86680-371-8 .

- Jürgen Theil, Walter Matznick: turning times. Prenzlau 1989–1993, Sutton-Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-86680-525-5 .

- Stephan Diller, Christoph Wunnicke (Eds.): Prenzlau and the Peaceful Revolution - a city in upheaval: 1985–1995 , accompanying document for the exhibition in the Kulturhistorisches Museum, Dominican Monastery Prenzlau, Prenzlau 2011.

- Klaus Neitmann (Hrsg.), Winfried Schich (Hrsg.), Stadt Prenzlau (Hrsg.): History of the City of Prenzlau. Geiger-Verlag, Horb am Neckar 2009, ISBN 978-3-86595-290-5 .

- Johann Samuel Seckt: Attempt of a history of the Uckermark capital Prenzlau. Volume 1, Prenzlau 1785 ( online in the Google book search)

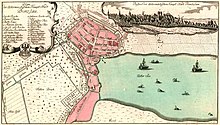

- Prentzlau in the Topographia Electoratus Brandenburgici et Ducatus Pomeraniae ( Matthäus Merian ) - Wikisource

Web links

- City of Prenzlau

- Tourist office Prenzlau e. V. ( Memento from May 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- u. a. with bibliography or library catalog and an online reading room

Individual evidence

- ↑ Population in the State of Brandenburg according to municipalities, offices and municipalities not subject to official registration on December 31, 2019 (XLSX file; 223 KB) (updated official population figures) ( help on this ).

- ↑ Prenzlau becomes Prentzlow - the first Low German station signage. February 22, 2018, accessed March 3, 2018 .

- ↑ Reinhard E. Fischer : The place names of the states of Brandenburg and Berlin. Volume 13 of the Brandenburg Historical Studies , be.bra Wissenschaft Verlag, Berlin-Brandenburg 2005, ISBN 3-937233-30-X , p. 113.

- ↑ City Book Brandenburg and Berlin (2000), p. 417. Prenzlau (Prenzlow) . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 13, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885-1892, p. 326. Prenzlau . In: Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon 1894–1896, Volume 13, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Service portal of the state administration Brandenburg. City of Prenzlau

- ↑ Incorporation of the communities of Dauer, Dedelow, Güstow, Klinkow and Schönwerder as well as the district Blindow of the community of Schenkenberg into the city of Prenzlau. Official Journal for Brandenburg Common Ministerial Gazette for the State of Brandenburg, Volume 12, 2001, Number 40, Potsdam, October 4, 2001, p. 634 bravors.brandenburg.de ( Memento of February 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ; PDF)

- ↑ Felix Escher : Many capitals and one metropolis. The “ranking” of Brandenburg cities in the Middle Ages and the early modern period (12th – 18th centuries). In: Provinz und Metropole, Metropole und Provinz, ed. v. Brandenburg State Office for Monument Preservation, 2009, p. 11.

- ↑ Bernhard Poten (2012): Concise dictionary of the total military sciences: Fifth volume: Ibrahim Pascha bis Krieg von 1859 , reprint of the standard work on military sciences from 1877, p. 348.

- ^ Meyers New Lexicon in eight volumes. Volume 6, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig 1964/65.

- ↑ Historical municipality register of the state of Brandenburg 1875 to 2005. District Uckermark (PDF) pp. 26–29

- ↑ Population in the state of Brandenburg from 1991 to 2017 according to independent cities, districts and municipalities , Table 7

- ^ Office for Statistics Berlin-Brandenburg (Ed.): Statistical report AI 7, A II 3, A III 3. Population development and population status in the state of Brandenburg (respective editions of the month of December)

- ↑ Result of the local elections in 2019

- ↑ Local elections October 26, 2003. Mayoral elections (PDF) p. 34

- ↑ Brandenburg Local Election Act, Section 74

- ^ Result of the mayoral election on September 24, 2017

- ↑ Coat of arms information on the service portal of the state administration of Brandenburg

- ^ Julius Ziegler: Prenzlau, the former capital of the Uckermark. Theophil Biller, Prenzlau 1886, p. 181.

- ↑ prenzlau.eu: twin cities of the city of Prenzlau (accessed on September 12, 2011).

- ↑ The four oldest churches are mentioned together for the first time in the second oldest document in Prenzlaus dated March 7, 1250 ( CDB 1st main part, 21st volume (Uckermark), p. 88 (excerpt)): “… Ecclesiam beate Dei genetricis et virginis Marie in dicta jam Prinslawe Civitate simulque alias annexas Ecclesias, videlicet beatorum Nicholai, Jacobi et Sabini. ” In the soon following document from 1256 (CDB 1st main part, volume 21, p. 91) it says (excerpt): “ Ecclesiam Marie Virginis cum sancti Jacobi, sancti Nicolai et sancti Sabini ecclesiis dependentibus from eadem ” .

- ↑ The church has the patronage of Saint Sabinus, not Saint Sabina (Julius Boehmer: The Prenzlauer Sankt-Sabinen-Kirche within the framework of the medieval diocese of Cammin , Prenzlau 1936, p. 29.)

- ↑ Heimann, Neitmann, Schich: Brandenburgisches Klosterbuch , Berlin 2007, pp. 967–977.

- ^ Karl Buchholtz: St. Nikolai, attempt at a chronicle. C. Vincent publisher, Prenzlau 1932

- ↑ Heimann, Neitmann, Schich: Brandenburgisches Klosterbuch , Berlin 2007, pp. 958–966

- ↑ Ursula Creutz: History of the former monasteries in the Diocese of Berlin in individual representations. Leipzig 1995, ISBN 3-89543-087-0 , pp. 218-221.

- ↑ Heimann, Neitmann, Schich: Brandenburgisches Klosterbuch , Berlin 2007, pp. 978–990.

- ↑ The renovation of the Heiliggeist Chapel is symbolic. In: Building and Urban Development - Press Releases. January 19, 2012. From Prenzlau.eu, accessed February 7, 2019.

- ↑ Claudia Marsal: Well then, cheers: Is a beer war threatening? In: Nordkurier - My Region - Prenzlau. December 16, 2014. From Nordkurier.de, accessed on February 7, 2019.

- ↑ Dehio Brandenburg p. 889; Ernst Badstübner : On the medieval art and architectural history of the city of Prenzlau , in: Klaus Neitmann / Winfried Schich / Stadt Prenzlau (ed.): History of the city of Prenzlau. Geiger-Verlag, Horb am Neckar 2009, pp. 353–391, here p. 387.

- ^ Uckermärkische Geschichtsverein zu Prenzlau e. V .: Roland statue. In: uckermaerkischer-geschichtsverein.de. 2014, archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on March 7, 2015 .

- ^ Regional studios and regional offices. Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg , July 28, 2006, accessed on August 15, 2010.

- ↑ Website of the State Garden Show (October 17, 2013)

- ^ Website of Wohnbau GmbH Prenzlau: History ( Memento of October 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (October 17, 2013).

- ↑ Press release of the Federal Government on the laying of the foundation stone for the hybrid power plant ( Memento of April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "Wind in the tank" - energy transition thanks to hydrogen. Spiegel Online , October 25, 2011

- ↑ Maps of the suitability for wind power use at 80 meters above ground. In: dwd.de. 2014, accessed December 24, 2014 .

- ↑ Maps of Germany and federal states on suitability for wind power use: We show in which regions wind power plants can be worthwhile if the EEG is observed .: Converter type: DWD standard. (PDF) (No longer available online.) In: dwd.de. June 27, 2013, formerly in the original ; accessed on December 22, 2014 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Oliver Schwers: Enertrag pays a wind power bonus. In: moz.de. April 21, 2012, accessed December 24, 2014 .

- ↑ IFE Eriksen AG opens a new representative office in Prenzlau. In: windkraft-journal.de. June 11, 2011, accessed December 24, 2014 .

- ↑ www.prenzlau-tourismus.de: Hotels, pensions and private rooms. In: prenzlau-tourismus.de. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014 ; accessed on December 21, 2014 .

- ↑ Hiking in the "Kleine Heide". In: Tourismusverein Prenzlau e. V. c / o city information. Retrieved May 17, 2015 .

- ↑ Contributions to the legal literature in the Prussian states ... Volume 4. Berlin 1780, pp. 237–267, ( online in the Google book search)

- ↑ Friedrich Christian Struve (Kiel scholar directory)

- ↑ Legenden des ESV , ESV Prenzlau website