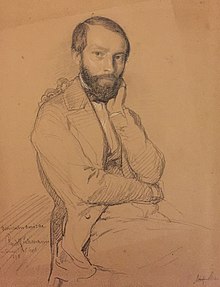

Adolf Stahr

Adolf Stahr (born October 22, 1805 in Prenzlau ; † October 3, 1876 in Wiesbaden ) was a German writer and historian.

Life

Adolf Wilhelm Theodor Stahr, son of the field preacher and later pastor in Wallmow (Uckermark) Johann Adam Stahr (1768–1839), attended grammar school in Prenzlau , went to Halle in 1825 at the request of his parents to study theology , but soon switched because of his enthusiasm for classical antiquity the subject and studied philology . During his studies, he joined the Halle fraternity, which was banned at the time, in 1825 and only escaped imprisonment because his younger brother Carl covered him up during police interrogations. After completing his studies, he was a teacher at the Royal Pedagogy of the Francke Foundations in Halle for ten years . In 1828 he received his doctorate as Dr. phil. with a work on the concept of tragedy in Aristotle . In Halle, Stahr published critical contributions to literature in the Halle yearbooks for German science and art, which were radically philosophical by his colleagues at the pedagogy Theodor Echtermeyer and Arnold Ruge . In 1834 Stahr married Marie Krätz (1813–1879), the daughter of the Leipzig school inspector August Kraetz and Sophie Caroline, née. Thierot. The marriage resulted in five children, three boys (Alwin, Adolf and Edo) and two girls (Anna and Helene).

In 1836 he was appointed vice principal and professor at the old grammar school in Oldenburg . In Oldenburg, in addition to his educational and journalistic work, he preferred the Oldenburg Theater , which - inspired by the example of Karl Immermann in Düsseldorf - he wanted to turn into a model political stage with his friends Ferdinand von Gall , Julius Mosen and others. While von Gall worked as a theater director and Mosen as a dramaturge from 1842, Stahr worked primarily as a theater critic. A collection of theater-critical works by Stahr was published in 1845 ( Oldenburg Theater Show , 2 volumes). During this time, the Grand Ducal Court Theater in Oldenburg went from being a relatively insignificant entertainment theater of the Biedermeier period to one of the most important venues for German political theater. Numerous pieces by modern authors such as Karl Gutzkow or Robert Prutz were performed here .

In Oldenburg, Stahr was instrumental in founding various sociable associations. In 1839 he was one of the co-founders of the literary-sociable association , which became the spiritual and sociable center of the Biedermeier period in the royal seat , and was president of the association from 1843 to 1844. He also founded the Philosophicum reading group . With Maximilian Heinrich Rüder , Carl Bucholtz and Dietrich Christian von Buttel , he founded the Neue Blätter für Stadt und Land in 1843 , the first liberal newspaper that wanted to educate the population to participate in political life and advocated the introduction of a constitution . After just one year, Stahr, like Buttel and Bucholtz, withdrew from the editorial board.

Because of his poor health, Stahr took leave of absence in 1845 and made long journeys through Italy , Switzerland and Paris , where he a. a. associated with Heinrich Heine . At the end of 1845, Stahr met the writer Fanny Lewald in Rome . A passionate relationship broke out between the two of them. In the years that followed, both made several trips, wrote and worked together. In 1852 Stahr gave up his job as a teacher, retired, moved to Berlin , divorced his first wife in 1854 and married Fanny Lewald in 1855. He continued to devote himself to his versatile literary work. In 1849 a three-volume novel The Republicans was published in Naples , but could not convince the critics. In 1849/50 a description of the revolution of 1848 in Prussia followed ( The Prussian Revolution , 2 vols.), Several travel books came out, art-historical works ( Torso. Art, Artists and Works of Art of the Elderly , 2 vols. 1854/55), translations by Aristotle , biographical and literary-historical works about Gotthold Ephraim Lessing ( GE Lessing. His life and his works , 1859, 2 vols.) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ( Goethe's Frauengestalten , 1865–68, 2 vols.), some of which are very high Reached editions. During this time, Stahr also dealt intensively with the political upheaval of the early Roman Empire and wrote several biographies on people from this era, which he published in the I. Guttentag publishing house in Berlin ( Tiberius , 1863; Cleopatra , 1864; Römische Kaiserfrauen , 1865 ; Agrippina, Nero's mother , 1867). A selection of scattered essays and reviews appeared in four volumes from 1871-75 ( Small writings on literature and art ).

In Berlin, too, Stahr sought contact with personalities from politics and culture and, together with his wife, continued the tradition of the salons of Bettina von Arnims and Rahel Varnhagens with regular salon meetings of the Berlin society . His political attitudes changed. At first he was liberal and campaigned for parliamentarism and against the Prussian state and its representatives, the Prussian king and Otto von Bismarck . After the outbreak of the revolution of 1848 , he became politically active and published books and political articles in various newspapers in this area. He also joined the German Progressive Party . Later he turned away from these positions, voted, like many members of the educated middle class , for the small German solution and became, as it were, an admirer of Otto von Bismarck.

Stahr vehemently opposed German small states and also showed pronounced hostility to the French, especially towards Emperor Napoleon III. which was also directed against Heinrich Heine and Heinrich von Kleist and their work. He advocated the Franco-Prussian War and welcomed the defeat of France and the establishment of the German Empire . In old age, the rejection of Heine also mixed with strong anti-Semitism .

Stahr's last years were marked by illness and increasing resignation. He suffered from severe pneumonia in 1875 and died a year later during a cure in Wiesbaden . He found his final resting place in the old cemetery there . His wife Fanny, who died in Dresden in 1889, was later buried at his side.

classification

Stahr was one of the most important and influential critics in pre- and post-March . Politically, he took a decidedly liberal position and was friends with many liberal-democratic politicians and publicists such as Arnold Ruge. His Lessing biography was dedicated to the Prussian democrat Johann Jacoby . After his death, Fanny Lewald canceled the assignment to Jacoby in a new edition and dedicated the work to Otto von Bismarck .

As a classical philologist, theater critic and writer, Stahr was controversial and at times exposed to vehement criticism. Nevertheless, he shaped the intellectual and cultural life of the city of Oldenburg in the 1830s and 1840s. Stahr's brother Karl Ludwig Stahr (1812–1863) was also active as a journalist.

In 1995, the Hamburg businessman Holger Cassens, at the suggestion of Gerhard Kegel, donated the “Adolf Stahr Prize” endowed with 4000 euros. It has been awarded every two years since 1996 for works in the literary and historical fields that have a direct connection to the Uckermark or the city of Prenzlau .

Works

- Aristotelia. Life, writings and pupils of Aristotle , Halle: Orphanage, 1830–32

- Aristotle with the Romans , Leipzig: Lehnhold, 1834

- Johann Heinrich Merck. A monument , Oldenburg: Schulze, 1840

- Bettina and her royal book , Hamburg: Verlags-Comptoir, 1844

- Theodor von Kobbe. A memorial stone , Oldenburg: Schulze, 1845

- One year in Italy , 3 vol., Oldenburg: Schulze, 1847–50

- The Republicans in Naples. Historical novel , 3 vols., Berlin: Schultze, 1849

- The Prussian Revolution , Oldenburg: Stalling, 1850 (2nd, increased edition there, 1851)

- Two months in Paris , 2 volumes, Oldenburg: Schulze, 1851

- Weimar and Jena. A diary , 2 volumes, Oldenburg: Schulze, 1852

- Torso. Art, artists and works of art of the elderly , 2 vols., Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1854–55

- After five years. Paris studies from 1855 , 2 volumes, Oldenburg: Schulze, 1857

- Sueton's Imperial Biographies. Translated into German by Adolf Stahr , Stuttgart: Hoffmann, 1857

- Herodian's history of the Roman Empire since Marcus Aurelius . German by Adolf Stahr. Stuttgart: Hoffmann, 1858

- GE Lessing: His life and his works , 2 vols., Berlin: Guttentag, 1859

- Aristotle and the effect of tragedy , Berlin: Guttentag, 1859

- Aristotle's Poetics. Translated and explained by Adolf Stahr , Stuttgart: Krais & Hoffmann, 1860

- Aristotle's Policy. Translated and explained by Carl Stahr and Adolf Stahr , Stuttgart: Krais & Hoffmann, 1860

- Autumn months in Northern Italy , Oldenburg: Schulze, 1860

- Fichte, the hero among German thinkers. A picture of life for the secular celebration of his birthday , Berlin: Janke, 1862

- Aristotle's Three Books of Oratory. Translated by Adolf Stahr , Stuttgart: Krais & Hoffmann, 1862

- Tiberius (pictures from antiquity) , Berlin: Guttentag, 1863

- Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. Translated and explained by Adolf Stahr , Stuttgart: Krais & Hoffmann, 1863

- Cleopatra (pictures from antiquity) , Berlin: Guttentag, 1864

- Roman imperial women , Berlin: Good Day, 1865

- Goethe's Frauengestalten , 2 volumes, Berlin: Guttentag, 1865–1868 (5th edition 1875)

- Agrippina, Nero's mother , Berlin: Guttentag, 1867

- A winter in Rome , Berlin: Guttentag, 1869 (together with Fanny Lewald )

- A piece of life. Poems , Berlin: Guttentag, 1869

- Tacitus' History of the Government of Emperors Claudius and Nero. (Annalen, Book XI-XVI.) Translated and explained by Adolf Stahr , Berlin: Guttentag, 1870

- He must go down! Storm bell calls against the burglar (on the Franco-German War ), Berlin: Guttentag, 1870

- From the youth: Memoirs , 2 vols., Schwerin: Hildebrand, 1870–77

- Small writings on literature and art , 4 vols., Berlin: Guttentag, 1871–75

- Ludwig Geiger (Ed.): From Adolf Stahr's estate. Letters from Stahr and letters to him , Oldenburg and Leipzig: Schulze, 1903

literature

- Ludwig Julius Fränkel: Stahr, Adolf Wilhelm Theodor . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 35, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, pp. 403-406.

- Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft. Volume II: Artists. Winter, Heidelberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8253-6813-5 , pp. 656-658.

- Raimund Hethey: Adolf Wilhelm Theodor Stahr. In: Hans Friedl u. a. (Ed.): Biographical manual for the history of the state of Oldenburg . Edited on behalf of the Oldenburg landscape. Isensee, Oldenburg 1992, ISBN 3-89442-135-5 , pp. 685 ff. ( Online ).

- Fanny Lewald / Adolf Stahr, A life on paper. The correspondence 1846-1852 . 3 vols. Edited by Gabriele Schneider and Renate Sternagel, Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2014/2015/2017, ISBN 978-3-8498-1046-7 (vol. 1), ISBN 978-3-8498-1104-4 (vol. 2 ), ISBN 978-3-8498-1204-1 (Vol. 3).

- Gabriele Schneider: Inappropriateness. Fanny Lewald and Adolf Stahr - "the four-legged bisexual ink animal". In: Fanny Lewald (1811-1889). Studies on a great European writer and intellectual. Edited by Christina Ujma, Vormärz-Studien Vol. 20, Bielefeld: Aisthesis 2011, ISBN 978-3-89528-807-4 , pp. 43–66.

Web links

- Literature by and about Adolf Stahr in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Adolf Stahr in the German Digital Library

- SUB Goettingen

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fanny Lewald / Adolf Stahr, A life on paper. The correspondence 1846-1852 , 3 vol., Ed. v. Gabriele Schneider and Renate Sternagel, Bielefeld 2014ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stahr, Adolf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German author and historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 22, 1805 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prenzlau |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 3, 1876 |

| Place of death | Wiesbaden |