Demmin city fortifications

The Demmin city fortifications probably enclosed the city of Demmin from the middle of the 13th century . The city fortifications, which were completed in the 15th century, were demonstrably repaired in the middle of the 16th century. During the Thirty Years War and the subsequent Swedish era , Demmin was expanded into a fortress. Hardly any other Pomeranian city, apart from Stralsund , was fought over as frequently and for as long as the Demmin fortress in the 17th and 18th centuries . In the second half of the 18th century, the fortifications were razed on the orders of Frederick the Great .

In addition to the Luisentor and the Powder Tower, there are still remnants of the city wall in the western part of the city. In the south and north of the old town there are still parts of the fortified ramparts that could not be dismantled for reasons of stability. To the east of the city center is a dry city moat.

history

12th to 16th centuries

The strategically favorable location of Demmin at the confluence of the Peene , Tollense and Trebel rivers was already used by the first Pomeranian dukes in the 12th century, who had the castle Haus Demmin built on an island in the marshland .

The market town, which had grown under the protection of a fortress house of the Pomeranian dukes, was expanded according to plan from 1236 and received Lübische law until 1249 . At this time, the construction of the city wall began. While the Kahldentor was mentioned as early as 1284, the actual wall was only mentioned in a document in 1340. For the contracts of the city of Demmin with Stralsund in 1265 and other cities in 1283, the military capability of the city was a decisive prerequisite for the alliance of the place. In 1301 the city was allowed to fortify its mills outside the walls.

During the First War of the Rügen Succession , Demmin was besieged by Mecklenburg troops in July 1327. Firing arrows at fire caused only minor damage.

After the introduction of the Reformation in Pomerania in 1534, the associated secularization of the Pomeranian monasteries and the accession to the Schmalkaldic League , Pomerania was also threatened with punitive action by the imperial troops in the middle of the 16th century. Therefore, in 1546 and 1547 the Demmin city fortifications were fundamentally repaired under the supervision of ducal officials. An additional wall was also built behind the trenches. In 1546 the Wallmeister received an annual salary of 222 Marks 6 Schillings, including the maintenance for his servant.

17th century

During the Thirty Years' War , Demmin was occupied by imperial troops led by Federigo Savelli in November 1627, soon after the surrender of Franzburg . In 1630 Savelli had the St. Mary's Church in front of the eastern moat demolished so as not to offer any cover to advancing enemies. In February 1631, Swedish troops from King Gustav II Adolphus holed up in the northeast and east of the city while cannons were being fired at at the same time. After the Swedes under Colonel Dodo von Knyphausen had captured Demmin's house and the Swedish artillery had shot a breach in the city wall, Savelli surrendered and received 1,000 men free withdrawal. King Gustav II Adolf ordered the city fortifications to be expanded, which happened over the next few years.

In August 1637 Demmin was besieged by imperial troops. First, a 300-strong detachment holed up on the dam between the Demmin house and the village of Vorwerk . It was under fire from the Swedes under the Reichszeugmeister Lennart Torstensson and finally stormed. In November 1637 there was a second siege and this time Demmin was enclosed by the imperial and troops from Saxony and Brandenburg. The north wall up to the Kuhtor was shot at with 26 heavy guns from three batteries and badly damaged. The Swedish crew of 600 surrendered.

In 1638 and 1639, the imperial troops stationed in Demmin were trapped in the city by the Swedes. The strength of the besiegers under Axel Lillie was not enough to overcome the fortifications. It was only after the Swedes spread false information about an allegedly intercepted reinforcement and supplies that the besieged surrendered. After the imperial withdrawal, the Swedes built Demmin from 1641 to 1659 into a contemporary fortress. The work was directed by Colonel Conrad Mardefelt , who lives in Demmin . In 1645 alone, the year the fortress was considered completed, expenditure from royal funds amounted to around 10,000 thalers.

It was not until the Second Northern War in 1656 and 1657 that further work was carried out on the reinforcement of the protective works, damage to the city wall was repaired and the armament was reinforced. Since there was now a lack of suitable wood in the Demmin forests, the Swedes brought 2000 spruce trunks from the Ueckermünder Heide to build palisades . In 1659 besieged troops led by Brandenburg field marshal Otto Christoph von Sparr Demmin. The besiegers built several redoubts around the city , from which the city was taken under fire. The outer ramparts of the city were undermined by them with two mine passages and the ravelins above them collapsed by blasting. The attackers succeeded in taking the outworks. After 28 days of siege, the Swedish occupation capitulated and withdrew to Stralsund. After the end of the war, however, the Brandenburg troops had to withdraw from Swedish Pomerania according to the contract.

During the Swedish-Brandenburg War in 1675, the fortifications, which were heavily damaged in 1659, were rebuilt under the direction of Field Marshal Conrad Mardefelt and Colonel von Blixen . From September 1676 Demmin was enclosed by Brandenburg troops under Feldzeugmeister Duke August von Holstein. The town was set on fire through the shelling of Demmin's house and another position. The fire, which lasted two days, destroyed almost all buildings, including the town church of St. Bartholomew . At the beginning of October the besiegers received reinforcements and, after further heavy fire, attacked the ravelin in front of the cow gate. The retreating Swedes blew up the mine tunnels prepared under the ravelin, killing 300 attackers. Five days later, the Swedes capitulated and were allowed to leave for Stralsund. After the Peace of Saint-Germain, however, the Brandenburgers had to vacate Western Pomerania again.

18th century

At the beginning of the 18th century the Demmin city fortifications were not defensible due to the siege during the Swedish-Brandenburg War. For lack of money, the Swedes had so far failed to repair the systems. In 1708 the fortification was inspected. Some gates could no longer be closed. The city wall had collapsed to a length of more than 8 meters. The Swedish government commissioned the magistrate with the reconstruction. Since nothing happened until 1711, the Swedes decided not to defend Demmin again during the Great Northern War . At the beginning of August 1711, they removed all useful war material and had 9 bridges in the Demmin area destroyed.

A few days later, Saxon cavalry came to Demmin, made makeshift repairs to the fortress and stayed in the city and the surrounding area until September 1712. In the winter of 1712–1713, Russian troops made quarters in Demmin and stayed there until the summer of 1713. In the Treaty of Schwedt, King Friedrich Wilhelm I received Western Pomerania south of the Peene for sequestration . The Prussian administration had Demmin's fortifications and ramparts expanded again. From 1720 Demmin and Old Western Pomerania belonged to Prussia.

Only during the Seven Years' War did fighting resume in Demmin. In the absence of the military of the Demmin garrison, Swedish troops invaded the city on September 15, 1757 under a pretext through the Holsten Gate and disarmed the vigilante groups. Under the leadership of Lieutenant General Hans Henrik von Liewen (the younger) , the Swedes began again with the expansion of the fortress. They restored the ravelins in front of the Kuhtor and two bastions at the Kahldentor. To the northeast of the city they built a half-moon hill (Demilune). In December Demmin was reoccupied by the Prussians after heavy fire. The Royal Prussian War Commissariat was temporarily relocated to Demmin. Between 1757 and 1763 Demmin was occupied eight times by the Swedes and recaptured by the Prussians just as often. The Demmin Fortress was last besieged by the Prussians from January 12th to 18th, 1759. The Swedes in the city had received orders from their commander in Lantinghausen to fight to the last man. On January 15th Demmin was hit by 5 batteries, the next day by 6 batteries with grenades weighing up to 100 pounds. The Swedish bastions that returned fire were soon put out of action. The attempt by the Prussian artillery to break through the walls failed, however. After the Prussians had conquered the Meyenkrebsbrücke and the Swedes under Colonel von Lilienberg had to fear a storm attack, they capitulated on January 18th.

On February 11, 1759, King Friedrich II ordered Demmin to be de-fortified. City walls and gates were allowed to remain in place, while the walls were to be razed and distributed as gardens to the citizens of Demmin. However, the city initially lacked the necessary labor and, above all, skilled people for the dismantling of the facilities. The Prussian government put pressure on the progress of the work and had it supervised by Lieutenant General von Manteuffel. Swedish troops occupied the city again in August. Under a Major von Wrangel they had walls erected east of the cow gate and a wall raised in the middle of the street, but then withdrew on November 2nd.

Only after the peace treaty were the city walls laid down and handed over to the 219 citizens of Demmin as wall gardens. However, they still had to level the parcels and clear them of rubble and rubble, and the stones found in the process had to be handed over to the city.

City wall and city gates

The walls that were preserved in the second half of the 18th century, according to the Demmin pastor and author of a town chronicle, Wilhelm Karl Stolle , were about 24 to 26 Rhenish feet (about 8 meters) high on the field side . In 1731 it was brought to a uniform height of 18 feet (about 6 meters) on the city side. There were towers in the wall that towered over it. In 1659 there were 10 with a round floor plan (rondelle) and 17 with a rectangular one. Most of the towers were on the east side, which was most exposed to attacks.

In addition to the four main gates, the Kuhtor, Frauentor, Kahldentor and Holstentor, Demmin had four other gates and gates.

Kuhtor / Luisentor

The Luisentor is the only remaining city gate in Demmin. It is at the end of Luisenstrasse. Field stones were built on the ground floor, the two upper floors and the stepped gable are made of brick .

After the city was de-fortified, it served as a prison from 1763 to 1895. The city renamed the Kuhtor to Luisentor in honor of Luise von Anhalt-Bernburg, the wife of Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig of Prussia , who stayed in Demminer Kuhstrasse on the journey to Putbus , after her departure in July 1821. Since then, the Kuhstrasse has also been called Luisenstrasse. From 1952 to 2002 the Luisentor served as a youth hostel.

Frauentor

The Frauentor was on Frauenstrasse, which led to the Marienkirche in front of the city. It was walled up (blinded) while the fortress was being built. The gate tower was destroyed either in 1631 by the imperial troops or in 1659 (1676?) By Brandenburg troops. The Frauentor existed as a blind gate until 1848.

Castle gate

This gate was on the south side of the city wall opposite the Demmin house. The name castle gate is supposed to refer to the fortress house of the dukes of Pomerania-Demmin, which however no longer existed in the 16th century. A bridge led from the castle gate over the ramparts, from where you could continue to Haus Demmin.

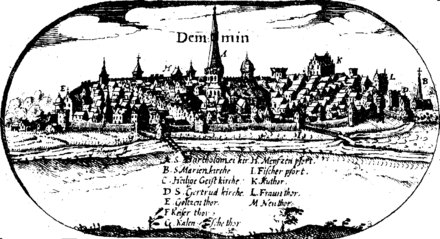

In the townscape of Merian 1652, on which the gate is open and has a pointed helmet, it was referred to as the Nietor (new gate). Hence the name porta nona (ninth gate) which can be found in the map of 1659. At that time the gate was walled up and without a spire.

The former location of the Festes Haus was specified in the accounts of the Demmin city treasury as Schlosskamp , on the wall and in front of the wall .

Fisherman's gate

This gate was on the extension of today's Fischerstrasse. It was referred to as the Visker Porten in old city records . This gate was still open in 1652, but walled up in 1659. It was probably only accessible to pedestrians who could get from here via a bridge over the city moat to Blumenburg and to the Kahldentor.

Kahldentor

The Kahldentor was called Calandisches Tor in the oldest records (1284) . The name referred to the von Caland family based in Demmin, some of which also spelled Kahlden . The Kahldentor is shown on the Lubin map as a double gate. The Kahldenbrücke crossing the Peene connected the city of Demmin with the important trade route to Magdeburg. While the Luebian law applied in the city , Schwerin law was applied in the lands of the Kahldentor.

The gate remained open during the Swedish occupation, but access from the outside was blocked by a jump , so that from 1652 the Kahlden Bridge could only be reached via the Holsten Gate. It was only made passable again when the city was de-fortified under the Prussian government in the second half of the 17th century. In 1824 the Kahldentor was torn down. The demolition had a volume of 111 loads of field stones and around 60,000 bricks were sold from it.

Holsten Gate

The Holsten Gate was on the north-western edge of the city wall. From there one reached over a dam to the Meyenkrebsbrücke , from where the trade routes to Stralsund, Greifswald and Wolgast could be reached. Around 1652 the Holsten Gate still had a pointed Gothic tower. It was walled up in the second half of the 17th century. Instead there was a breakthrough in the wall to the north, which was called the New Gate . In 1728 King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia had the Holsten Gate reopened and covered with a transverse roof. In the form of a house with a breakthrough, the Holsten Gate existed until it was demolished in 1862.

Mentzer Gate

The Mentzer Gate, referred to as Mentzerporten in the town of Demmin's pawnbook in 1524 , was located in the north wall approximately opposite the Fischertor in the south wall. A footpath led through the gate to the Richtgraben and the Bürgerwiese. In 1567, Demmin's first aqueduct was laid through this gate.

Christian Gate

The Christian Gate was recorded in Merian's city map, but was never mentioned in Demmin's pawn books. Possibly the roads leading to the Richtgraben and Nonnenberg started from him. In the time of the fortress it was probably walled up, as it could not be passable by upstream entrenchments.

Ramparts and ditches

The earth wall, built in the middle of the 16th century, was no longer defensible during the Thirty Years' War. When the city was fortified by the Swedes from 1631, the ramparts were therefore renewed according to the state of fortress architecture at that time.

A rampart path was laid out around the city walls, followed by the main rampart outside. In this 6 bastions and some smaller sub-bastions were built. The main wall was followed by the lower wall, which provided cover with a pile of earth as a parapet. The fortress moat was located around the lower wall, following the shape of the ramparts and bastions. This was fed with water from Tollense and Peene. Outside the ditch was a countercarp .

External works for the defense of the wall were located in the west and east of the city. In the north and south they were not necessary because of the swampy terrain. The outer works were laid out as ravelins in front of the Kuhwall, in front of the Kahldenwall between Kahldentor and Fischerpforte and in front of the Holstentor. There were also palisades. In 1757 the Swedes built a half-moon hill (demi-lune) in front of the north-eastern wall.

External defenses

Up until the Thirty Years War there were several fortified buildings in the vicinity of the Demmin suburbs, which were referred to as castles in the city books. Their tasks included monitoring trade routes and collecting tariffs. Such systems were located in the Demminer Vorwerke Stuterhof and Meyenkrebs, on an outer ditch east of the Kuhtor and about 5 kilometers from the city at Quitzerow and Siedenbrünzow . The last two were near the Pensiner Graben, a damp lowland that was a natural obstacle.

To the south of the Peene, in the area of today's Stuterhof district , was the Bullenburg at the beginning of the 14th century . This was mentioned in a document from Duke Wartislaw IV in 1322 , when it was held by the Demminers in a conflict with the Mecklenburgers. It was mentioned for the last time as early as 1329, when Barnim IV signed a document there.

literature

- Karl Goetze: History of the city of Demmin edited on the basis of the Demmin Council Archives, the Stollesche Chronik and other sources . Demmin 1903, reprint 1997, ISBN 3-89557-077-X

- Wolfgang Fuhrmann: The Hanseatic City of Demmin in old and new views . GEROS Verlag Neubrandenburg 1998, ISBN 3-935721-00-5

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 24

- ↑ Horst-Diether Schroeder: The First War of the Rügen Succession - Causes, Course and Results . In: Contributions to the history of Western Pomerania: the Demmin Colloquia 1985–1994 . Page 136. Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin 1997, ISBN 3-931185-11-7 .

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 260

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 27

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 293

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 294

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 34

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 303–304

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Pages 305–306

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 36

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 311

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 37

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 318-320

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 338-320

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Pages 390–392

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 392–394

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 407

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Pages 429–441

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 441–443

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 446–447

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 452–453

- ↑ a b Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 44

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 26

- ↑ a b c Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 39

- ↑ a b Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Pages 42–43

- ↑ a b Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 201

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Page 43

- ^ Goetze: History of the city of Demmin . Pages 43–44

- ^ Karl Goetze: History of the city of Demmin. Pages 45–46

- ^ A b Karl Goetze: History of the city of Demmin. Pages 27–33

Coordinates: 53 ° 54 ′ 26 ″ N , 13 ° 2 ′ 2 ″ E