Brandenburg-Prussia

The name Brandenburg-Prussia denotes the entire territories of the Electors of Brandenburg from the House of Hohenzollern in the period between the acquisition of the Duchy of Prussia in 1618 and its elevation to kings in Prussia from 1701.

Originally, the possessions of the Hohenzollern limited Marquis to the Mark Brandenburg itself. By dynastic inheritances and purchases at the beginning of the 17th century, they enlarged their possessions, so that was a widely scattered territory, which initially only by the person of the ruler was connected. The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 decisively strengthened the position of Brandenburg-Prussia.

The term is mainly used in historical studies in order to differentiate the entire Hohenzollernland from the individual parts of the country in the respective context. With the coronation of Frederick III. On January 18, 1701, the fragmented and loosely held together parts of the country with the newly founded Kingdom of Prussia were converted into a real union, which resulted in a central state. The term Brandenburg-Prussia is sometimes used for the period after 1701 to emphasize the reference to the Brandenburg origin of the Prussian state.

history

Acquisition of new parts of the country (1614-1618)

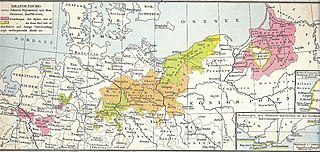

Red = acquisitions by Johann Sigismund 1608–1619

Green and yellow = acquisitions by the Great Elector 1640–1688

The policy of the Hohenzollern was aimed at increasing power through the acquisition of new lands. The respective rulers tried to achieve this through a clever marriage policy in order to obtain inheritance claims in the case of extinct ruling houses.

The then electoral prince Johann Sigismund married Anna on October 30, 1594 , the daughter of the Prussian Duke Albrecht Friedrich from the Ansbach line of the Franconian Hohenzollern.

The father of the electoral prince, the Brandenburg elector Joachim Friedrich, took over the reign of the Prussian duke over the duchy of Prussia in 1605 after the mentally ill Albrecht Friedrich became incapable of government . In 1608 Johann Sigismund became the new Elector of Brandenburg.

After the death of Johann Wilhelm , the last Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , a dispute about the vacant Duchy broke out in 1609 between the main heirs, the Brandenburg Elector Johann Sigismund and Wolfgang Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg , the so-called Jülich-Klevische Succession dispute . In the Treaty of Xanten of November 12, 1614, the Brandenburg Elector succeeded in asserting his claim to the Duchy of Kleve , the County of Mark and the County of Ravensberg .

With the death of his father-in-law Albrecht Friedrich, who was the last Franconian Hohenzoller Duke of Prussia, Johann Sigismund also officially became Duke of Prussia in 1618. Brandenburg and Prussia have been linked in personal union ever since . The Elector of Brandenburg initially received the Duchy of Prussia from the Polish King as a fief , until the Treaty of Wehlau finally granted the Elector of Brandenburg full sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia in 1657 .

Thirty Years War (1618-1648)

The newly acquired secondary territories initially remained spatially, politically and economically isolated from the Mark Brandenburg as the core state. The individual parts of the country were only connected to one another by the ruling person from the Hohenzollern family. There was no common national awareness or a holistic national policy under Elector Georg Wilhelm . Instead, the individual parts of the country retained their own national constitutions , traditions, structures and regional elites. In addition to the Calvinist elector, the Catholic Chancellor Adam von Schwarzenberg , the state leadership in Brandenburg-Prussia consisted primarily of Protestant councilors.

When the Thirty Years War broke out in 1618 , the Hohenzollernland was initially spared. The new Elector Georg Wilhelm, who succeeded Johann Sigismund at the end of 1619, was unable to resolutely defy foreign policy developments from his central province. From 1626 the Mark Brandenburg was visibly devastated.

After Brandenburg-Prussia stood on the side of the rebellious Bohemians and the Protestant imperial estates at the beginning of the Thirty Years' War , Schwarzenberg brought about the transition to the imperial side in 1626 , but this did not bring the longed-for relief from the burdens of war. In cooperation with Saxony , Brandenburg tried to form a third party to form the imperial constitution at the Leipzig Convention , but it broke up again immediately after an imperial army destroyed Magdeburg . When Gustav Adolf's army of Sweden occupied Brandenburg after landing on Usedom, the elector changed sides again together with Saxony. In the Peace of Prague of 1635 Brandenburg again changed sides, since the fortunes of war had meanwhile turned against the Swedes again. Then the country was occupied again by the Swedes. Since the march was ruled alternately by the imperial troops or the Swedes at the end of his reign, the elector often fled to his duchy of Prussia (including from 1627 to 1630) and his Rhine provinces, leaving behind a governor. With the elector's flight, the Kurmark was surrendered to any arbitrariness by external powers.

Elector Georg Wilhelm died on December 1, 1640 in Königsberg . The new elector, Friedrich Wilhelm , began to develop a central state out of the patchwork quilt by establishing common institutional structures.

Expansion of the central state (1640–1701)

Under Friedrich Wilhelm (1640–1688)

The Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm traveled to Warsaw in October 1641 . The Catholic King of Poland, Władysław IV. Wasa , supreme liege lord of Prussia, confirmed the young prince as Duke of Prussia on October 8th. Thereupon the Königsbergers gave him a splendid reception on October 31, 1641. This was the last time a Prussian ruler received recognition from a Polish king since 1525.

In the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 the Elector of Hinterpommern was able to acquire the entitlement to the Archbishopric of Magdeburg (attack in 1680) as well as the Halberstadt Monastery and the Principality of Minden , which together corresponded to an area of around 20,000 km². Despite these land gains, the situation worsened for the elector because the parts of the country were partly isolated and far apart.

Brandenburg-Prussia was now surrounded by overpowering states like the new great power Sweden in the north, which could threaten the Mark and the Duchy of Prussia at any time, France , which had access to the western Rhine provinces at any time, Poland in the east, who was the liege lord of the Duchy of Prussia, and in the south-east lay the Habsburg monarchy . Thus, the fates of the individual parts of the country were increasingly closely linked to those of the others, so that the history of the individual areas was from then on limited to the internal and local conditions of the respective countries.

After the war, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm, later called the "Great Elector", pursued a cautious rocking policy between the great powers in order to develop his economically and militarily weak countries. After initially supporting imperial politics, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm took over leadership of the Reichstag opposition in 1653 . His Foreign Policy Minister von Waldeck , who was now emerging, drafted the plan for an anti-Habsburg union under the leadership of Kurbrandenburg, which should also seek contact with France. But it was only possible to conclude a minor defensive alliance with the Guelph dukes and Hesse-Kassel in July 1655.

The Szczecin border recession of 1653 regulated the demarcation between Brandenburg and Sweden in Pomerania : In the previous peace negotiations in Osnabrück it had been agreed that Sweden and Brandenburg should regulate the specific demarcation of the boundaries in bilateral agreements. In the Peace of Westphalia, Brandenburg was only awarded Western Pomerania . In addition, Sweden delayed the surrender of Hinterpommern until May 1653. The last Swedish troops withdrew from Brandenburg five years after the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia and only when the elector had bought the withdrawal through the emperor's mediation.

When Poland-Lithuania was weakened as a result of the Northern War from 1656 to 1660 , the Elector was able to remove the Duchy of Prussia from Polish suzerainty in the Treaty of Wehlau in 1657 . In the Peace of Oliva of 1660, the sovereignty of the duchy was finally recognized. This was a crucial prerequisite for his elevation to the Kingdom of Prussia under the son of the Great Elector.

Friedrich Wilhelm carried out economic reforms and built a powerful standing army with up to 30,000 soldiers from the small Kurbrandenburg army of just a few thousand men . The estates were disempowered in favor of an absolutist central administration, whereby he increasingly succeeded in effectively connecting the territories with one another. The expansion of the central state depended above all on secure financing in the form of tax permits, of which the elector, in turn, was dependent on the approval of the estates. At the meeting of the Brandenburg state parliament in 1653, the elector succeeded in getting taxes approved by the estates amounting to 530,000 thalers. This sum was to be paid in installments over five years according to the previously agreed quotation rule, 41% of the taxes had to be paid by the landed gentry and 59% of the sum by the cities. In return, the elector confirmed privileges for the estates, which were primarily at the expense of the peasants. Unbearable compulsory labor , an intensification of serfdom and the plundering and subsequent buying up of farms were the result.

In addition, he pushed ahead with the construction of a Brandenburg fleet and acquired the Groß Friedrichsburg colony on the West African Gold Coast in what is now Ghana.

The Secret Council , the most powerful authority in the Electorate of Brandenburg since it was founded in 1604, which met in the Castle of Cölln , grew beyond its original function as the Brandenburg state authority after 1648 and gained national importance. According to the files received, the Secret Council dealt with state matters in the areas outside of Brandenburg as a whole from 1654. The highest Brandenburg state college thus became the central authority of Brandenburg-Prussia. The state colleges of the other areas were instead more and more subordinated to the Privy Council. However, by this point the Secret Council had passed its peak of power. The Hofkammer , founded in 1689, was of greater importance as an organization for the entire state. Other state authorities based in Berlin were the Lehnskanzlei, the Secret Chancellery and the Chamber Court. In the 17th century, however, their maintenance was largely paid from Brandenburg funds, while the court treasury was already fed from state funds.

When the Great Elector died on May 9, 1688, he had turned his country from a torn state structure that was helpless and powerless in foreign policy into a middle power recognized by all the great powers of the time. In addition, Brandenburg-Prussia had risen to become the most powerful territory in the empire after Austria .

In 1688 the size of the Hohenzollerland totaled 112,660 km² with 1.5 million inhabitants (1640: about 1 million inhabitants). The tax revenue amounted to 1.677 million thalers, the subsidy payments amounted to 1.7 million thalers in 1688. Together, the state of Brandenburg-Prussia had a state budget of 3.4 million thalers, which represents a threefold increase in state income compared to when the elector took office in 1640 (a total of 1 million thalers, 400,000 thalers from taxes).

Under Friedrich III. (1688–1701)

One week after the Elector's death, the Secret Council met for the first time, chaired by the new Elector Friedrich III. for the opening of the father's will. In violation of the house laws of the Hohenzollerns that had been in force since 1473, Brandenburg-Prussia was to be divided between the five sons of Friedrich Wilhelm, i.e. Friedrich and his four half-brothers. After lengthy negotiations and detailed legal opinions, including by Eberhard von Danckelman , the heir to the throne succeeded in asserting himself against his siblings by 1692 and preserving the unity of the country. Friedrich's half-brothers were resigned as Margraves of Brandenburg-Schwedt .

Elevation of rank - establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701

Copper engraving by Peter Schenk , 1703

In order to prevent Brandenburg-Prussia from being dissolved at any time through the division of inheritance, the new elector pursued the idea of an increase in rank from 1691 in order to unite the scattered Hohenzollern territories and to give them a cohesive framework . He completed this project in 1701 with his royal coronation .

However, Emperor Leopold I had made it a condition that Frederick was not allowed to apply the desired royal title to the Electorate of Brandenburg, but only to the Duchy of Prussia, which was outside the Holy Roman Empire. The new Prussian king was also only allowed to call himself King in Prussia, not of Prussia, because the part of Prussia under his control did not include all of Prussia, but only the eastern part of it. The other part, Prussia with a royal Polish portion , was under the Polish crown until 1772 .

Domestically, the coronation promoted the state unity of the geographically far apart and economically very different Hohenzollern territories. The ruler's ambassadors, authorities and army were henceforth called "royal" and carried the colors and coat of arms of Prussia. The name "Prussia" and "Prussian" was therefore carried over to all Hohenzollern areas in the course of the 18th century, with the exception of the southern German principalities of Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen , which only became part of the State of Prussia in 1850. The name of the most important part of the Hohenzollern region at all times, the Kurmark Brandenburg , lost its meaning.

For the further history from 1701 see Kingdom of Prussia

Economic history

Cameralistic economic policy (1640–1675)

The Margraviate of Brandenburg, which had been particularly devastated during the Thirty Years War, was greatly impoverished in 1648 compared to other German states such as Saxony or Habsburg Austria . Large stretches of land in the Mark Brandenburg were deserted and general economic activity was paralyzed.

Under the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm , economic policy remained stuck to the thinking of German cameralism until 1675 . It was an important goal of the elector to increase his own income, primarily from the electoral domains . Regular income of his own should make the elector more independent of the estates and increase the princely power. In the 17th century the corporate state in Brandenburg-Prussia was still strong and the estates also approved the elector's financial resources. They thus possessed an important instrument of power in order to be able to exert pressure on the elector's policy.

Significant achievements were made in the field of infrastructure in those years. The elector founded the Brandenburg State Postal Service in 1649 and tried since 1653 to get inland shipping going. The construction of the Müllros Canal (connection between Oder and Spree) from 1662 to 1669 represented the first major transport management measure by a German sovereign. The measures in the area of infrastructure created new, accelerated and cheaper transport connections and thus set incentives for more active trading activity.

Until the Battle of Fehrbellin in 1675, the repair of the direct damage caused by the Thirty Years' War was the focus of state economic policy. It was not until the following phase from 1676 onwards that a broad-based economy was built. From then on, the Elector's mercantilist measures made themselves felt in terms of a targeted, long-term economic development.

New mercantilist economic policy from 1676

The Elector's new mercantilist economic policy was based heavily on the French model, with the emphasis here on promoting trade and manufacturing . This new "industrial policy" originated in the Mark Brandenburg and was gradually transferred to the other areas.

Examples of the new mercantilist economic policy:

- A sugar boiler plant established in Berlin in 1679 was converted into the first Brandenburg stock corporation in 1680. The elector contributed 10,000 thalers.

- In 1681 a tobacco mill was built (by the Berlin mayors Bartholdi and Senning)

- 1686 Johann Andreas Krautt founded a gold and silver wire drawing shop .

In many cases these foundations were only temporary. The reasons lay in the state's lack of money and the insufficient number and power of private investors to survive the initial deficit. So the new manufacturing policy relied decisively on the promotion of local production, especially the wool factories. A typical mercantilist phenomenon was also represented by the founding of Commercien-Collegien (February 23, 1684), which as a kind of authority had administrative powers and at the same time operated the economic policy of the state through advice. The beginnings of the country's economic recovery took many small steps.

The state finances could be restructured and increased by a new tax system in which the excise tax was introduced as a consumption tax in 1684 . At the same time, the excise permits a more precise control of the production and movement of goods, but also the monitoring of export and import bans, than could be handled with tariffs alone. Through extensive peuplication measures , i.e. the attraction and settlement of specialists from many European countries ( Edict of Potsdam of October 29, 1685), Friedrich Wilhelm succeeded in bringing new specialist knowledge and manpower to the technologically backward Brandenburg.

As a result of this bundle of funding against the background of pan-European economic growth, new branches of industry emerged in Brandenburg-Prussia:

- Silk manufacture

- Sergemanufaktur

- Gauze manufacture

- Ribbon manufacture

- Wallpaper manufacturer

- Silk construction

- Gold and silver wikerei

- Chasing and enamelling

- Manufacture of fine cloths and hats

- Hosiery technique

- Stuff printing

- Whitewash

- Oil preparation

- Light pouring

- Mirror manufacturing

- Playing card production

In contrast to the leading economic powers England, France and especially the Netherlands, the Hohenzollerland lacked a strong economically active bourgeoisie that could have been the bearer of economic progress. Innovations and economic growth strategies could primarily only be set in motion by the state administration. Another peculiarity of this state structure was the Calvinist confession of the sovereigns. The Calvinist way of life allowed the Prussian state elite to develop a work ethic in which economic success, efficiency and public benefit were the primary goals of the state administration. These governance qualities were an important factor in Prussia's economic success.

On the other hand, the state appeared as the greatest economic burden, because the treasury withdrew considerable amounts of money from the economic cycle for the military.

Hohenzollern domains

The territory of Frederick III. divided into different areas that stretched from the Rhine to the Memel . Two parts of the country stood out due to their size: the Mark Brandenburg and the independent Duchy of Prussia .

In 1619, in the most important part of the Hohenzollern region, the Mark Brandenburg, the national debt amounted to 2,142,000 Reichstaler . The Mark lived exclusively from agriculture. Higher goods all had to be imported. The Duchy of Prussia had developed even more strongly than Brandenburg. The German upper class brought in by the Teutonic Order in the Middle Ages had developed into a successfully producing and trading class. This class made considerable fortunes in the cities. The Duchy of Prussia remained economically isolated from the state as a whole for a long time. This applies in particular to Königsberg as the most important trading city in Brandenburg-Prussia. The city flourished economically in the first half of the 17th century, but lost a large part of the prosperity it had achieved due to wars, plague and taxation. The volume of trade that Königsberg had in the Thirty Years' War was not reached again until the 18th century.

The provinces in the west did not develop any economic relations with the state as a whole in the 17th century and far beyond. This was due to the physical distance and the many customs offices along the trade routes ( 46 between Cleve and Mark Brandenburg alone).

Hohenzollern parts of the country:

- Mark Brandenburg (1415)

- County Mark (1609)

- Duchy of Kleve (1614)

- County Ravensberg (1614)

- Duchy of Prussia (1618)

- Western Pomerania (1648)

- Principality of Minden (1648)

- Principality of Halberstadt (1648)

- Duchy of Magdeburg (1680)

See also

literature

- Otto Hintze : The Hohenzollern and their work - five hundred years of patriotic history (1415–1915). Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin 1915, reprint of the original edition: Hamburg / Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-490-33515-5

- Ludwig Hüttel: Friedrich-Wilhelm von Brandenburg the Great Elector 1620–1688 , Süddeutscher Verlag, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-7991-6108-2

- Ingrid Mittenzwei , Erika Herzfeld: Brandenburg-Prussia 1648 to 1798. The age of absolutism in text and image. Berlin (Ost) 1987, ISBN 3-373-00004-1 (appendix with index of symbols, register of persons and picture credits).

- Ingo Materna , Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Brandenburg history. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-05-002508-5 .

- Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-05392-3 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Ingo Materna, Wolfgang Ribbe, Kurt Adamy: Brandenburgische Geschichte, p. 292.

- ↑ https://www.preussenchronik.de/episode_jsp/key=chronologie_001180.html

- ↑ https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd11853596X.html >

- ↑ http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=3541&language=german

- ^ Ingo Materna, Wolfgang Ribbe, Kurt Adamy: Brandenburgische Geschichte, p. 326.

- ↑ Werner Schmidt, p. 85

- ↑ Prussia Year Book - An Almanach, p. 29

- ↑ Friedrich-Wilhelm Henning: Das vorindustrielle Deutschland 800 to 1800 , Schöningh, Paderborn, 3rd ed. 1977, chapter The heyday of cameralism , pp. 233–287, esp. Section 2 The Thirty Years War and its Consequences , pp. 238 ff .

- ^ Francis L. Carsten: Manor and noble power. In: Manfred Schlenke (Ed.): Prussia. Contributions to a Political Culture , p. 28 ff., And the chapter The Estates Agricultural Society. In: Peter Brandt (arr.): Prussia. On the social history of a state , p. 23 ff.

- ↑ Hans Bentzien: Under the Red and Black Eagle. Verlag Volk & Welt, Berlin 1992, p. 58.