India trade

In historical studies, trade in India refers to the trade relations between the state structures in the Mediterranean (or Europe ) and those of India (including the neighboring regions in the Indian Ocean), which extend from antiquity to the early modern period , with the trade routes from India to Central Asia , Southeast Asia and East Asia (China) ranged.

The ancient Indian trade

The earliest contacts between the West and India go back to the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire , which extended to the border of India. The Greek geographer Skylax , who was in Persian service, traveled in the late 6th century BC. The outskirts of India ( Sindh ), but his records are only fragmentary. Herodotus went into more detail about India in his Histories , although fairytale-like stories flowed into the description, which were even more pronounced in Ktesias of Knidos . The knowledge of the Greeks about ancient India was before the Alexander Zug in the late 4th century BC. BC overall very sketchy and often characterized by fairytale-like stories. Since Hellenism , there have been closer contacts between the ancient Mediterranean world and India, which was reflected in diplomatic relations, among other things, even though these were never completely continuous due to the great distance. But there were several works about India, in which more detailed information was incorporated (see Indica ).

The trade between Ptolemaic Egypt and India by sea , which developed under Hellenism, was of great importance . Long-distance trade between the Mediterranean and India was significantly intensified during the Roman Empire . Several sources are available for Roman-Indian relations , with the Periplus Maris Erythraei being of particular importance. This also lists the most important Indian ports that functioned as the main transshipment points , including Barbarikon (in the Indus region) and Poduke (in southern India). During this period, trade routes between India and the west ran both over land and (especially since the monsoon routes were opened up at the end of the 2nd century BC) by sea. The Ptolemies had already traded with India and apparently made use of the knowledge of Indian pilots, during which time the island of Socotra and the port of Aden in Himyar were important pivots. A central point here was the linking of political and fiscal interests, with Ptolemies benefiting from the maritime economy through taxes.

The overland routes of the camel caravans over the so-called Silk Road were quite ramified, but met in the Arab-Syrian region. The main routes in China led from Xi'an via Lanzhou to the west, then divided into a northern route (north of the Taklamakan via Turfan ) and a southern route (via Dunhuang and Yarkand ), which met again in Kashgar . It went on via Marakanda through northern Persia, then via Mesopotamia and Syria ( Palmyra being an important hub) to the Mediterranean Sea to Antioch . Branches of the Silk Road also led to India and, with the routes further west, formed a wide-ranging trade network.

The trade by sea ran mainly from the port of Myos Hormos on the Red Sea via Adulis , then along the south coast of the Arabian Peninsula to the ports on the Indus and further down the Indian Malabar coast , later even to Sri Lanka . In this context, Pliny the Elder reports three sea routes to India (middle of the 1st century): One led past the Syagron promontory (Ras Fartak) on the Arab south coast and ended in the aforementioned port of Barbarikon on the Indus, the second followed from Syagron Zigeros on the Indian west coast, the third finally went from the Arabian Okelis to Muziris in southwestern India.

According to Strabo , as early as the time of Augustus , around 120 ships made the journey to India each year to return with goods that were then imported to Alexandria and further into the empire. The imported goods (from India and other stays on the way) were mainly luxury goods, especially spices, silk from the "land of the Serer " ( Empire of China ), precious stones, pearls and ivory; Ceramic products, glassware and textile products were exported to India. It cannot be assumed that the trade balance was balanced; the funds used by the Romans are likely to have been considerable. Pliny the Elder puts the annual expenditure on goods from India, China and Arabia at 100 million sesterces. However, in recent research, this assessment is viewed more critically, as a not small part of it flowed back to the state via taxes etc. In any case, the ancient trade in India is regarded as an early form of globalization due to the interlinking of the different areas associated with it.

The very intensive trade between the Roman Empire and India was initially interrupted in connection with the imperial crisis of the 3rd century and the rise of the New Persian Sassanid Empire in the 3rd century or was in decline during this time. The lucrative Indian trade increased again in late antiquity ; This was now mainly done by sea and was controlled to a large extent by Persian middlemen. Apart from that, there was an exchange of goods and ideas between East and West throughout late antiquity, and overland routes continued to exist. In late ancient Central Asia the Sogdians played an important role in the silk trade, but due to Persian resistance they could not open it to the west (see Maniakh ); the Persians insisted on controlling the silk trade through Persia themselves. Indian traders were also active in the western Indian Ocean and probably also in the Red Sea from the Hellenistic period until the late high imperial period.

The Sassanids seem to have maintained intensive trade contacts with India and to have monopolized parts of the trade. The already latent points of conflict between East and Persia (see also Roman-Persian Wars ) were thereby further fueled. The Eastern Roman intervention in favor of the Christian empire of Aksum in southern Arabia around 525 should also be seen in this context (see Ella Asbeha ), as important trade routes between east and west ran here. The volume of trade seems to have been not insignificant even in late antiquity, at least until the 6th century, with the port of Berenike now largely taking on the role of Myos Hormos.

India trade in the early modern period

Starting position

With the rise of Islam and the Arab conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries, trade in India was initially almost completely cut, especially since the Byzantine Empire , which was struggling to survive, no longer had sufficient funds or set other priorities and other trade routes emerged. Trade in India with the West was under the control of Muslim traders during the Middle Ages . They benefited from the fact that the area of the Indian Ocean - including the East African coast and Southeast Asia - had been a unified trading and economic area since the mid-14th century. In the Indian Ocean area, Arab, Persian and Indian traders apparently cooperated side by side.

Goods such as spices, silk and precious stones were transported from India to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. From there it went overland to the Levant , where bulk goods were also exported. The goods then made their way to Christian Latin Europe mainly via the Venice hub . Pepper was one of the most sought-after spices in Europe in the 15th century, but only a fraction of Indian pepper (which made up the majority of the total production of over 6,000 tons in the period around 1515/20) was used there; the majority came to the Asian market and was mainly exported to China.

The opening of the trading area in the Indian Ocean by the Portuguese and the Estado da India

In order to eliminate the Muslim middlemen, at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the Europeans endeavored to discover the sea route to India around Africa. The Kingdom of Portugal played a central role in this. After the conquest of Ceuta in 1415, Portuguese seafarers had advanced further and further along the African west coast, with the crown pursuing economic and commercial interests at an early stage (including the search for gold deposits). In 1434 the Portuguese circumnavigated Cape Bojador , which is considered impassable , in 1460 they reached Sierra Leone , at the beginning of the 1480s the Congo and in 1488 the Cape of Good Hope .

The journey to India itself was first made by Vasco da Gama , whose journey is well documented in the diary of a participant ( Roteiro ) who reached Kalikut on the Malabar coast in May 1498 . The Portuguese made further voyages both in the Atlantic and in the entire Indian Ocean, which considerably expanded the experience of the Europeans and also set in motion a cultural transfer; Portugal became a major overseas power.

Through these voyages of the Portuguese (see also Portuguese India Armadas ) the opening of the Asian sea area for the Europeans was successful; This laid the foundation for the subsequent European expansion in the Asian region. In India, however, this process was partly marked by tensions between the Christian Europeans, the local Muslim traders and the Indian regional rulers. For example, there was an open conflict between da Gama and the ruler of Kalikut (the Samorin), with the Portuguese being militarily superior. When two Muslims asked what the Portuguese had to do in India, da Gama replied tersely that they were looking for Christians and spices. Christian missionary attempts made things even more difficult , especially since the actions of the Portuguese crown were initially shaped by the idea of the crusade .

As early as the first third of the 16th century, the systematic establishment of bases (often with factories ) to secure trade along the West African (where there were already selective bases) and the East African coast, in India and Southeast Asia. This ultimately resulted in a Portuguese overseas empire, the Estado da India with its headquarters in Goa , which was conquered in 1510. In 1506 the first Portuguese landed in Sri Lanka (where cinnamon was planted in great demand) and in the following decades began to build up bases and alliances there. After conquering Malacca in 1511 , the Portuguese also controlled the western sea route to the Spice Islands ( Moluccas ), whose exotic spices were in great demand from Europe to the Islamic region and whose trade brought rich profits, with the Portuguese soon competing with other European players . Indirectly, the gate to the Empire of China opened for the Portuguese, where shortly afterwards a first Portuguese embassy under Tomé Pires set out, but its mission failed catastrophically.

Trade with India was extremely profitable, especially since India was one of the largest markets in the world at that time in terms of population and economic strength. The rapid success of the Portuguese can be explained, among other things, by their superior weaponry at sea. When they arrived around 1500 there were in fact hardly any warships in the Indian Ocean, especially with cannons, while the Portuguese ships were all armed. Several times later the Portuguese managed to successfully eliminate enemy ships during combat operations.

The Estado da India - which was primarily the work of the energetic Afonso de Albuquerque - was not a typical colonial empire , but primarily a system of bases; nowhere was Portuguese influence more than a few miles inland. In Asia, the Portuguese were primarily concerned with profitable trade and its protection, not with territorial conquest. This comparatively “low profile” was helpful insofar as the political conditions on the ground were affected rather marginally, despite the tensions mentioned at the beginning of the Portuguese advance into the Indian Ocean, with the Portuguese cleverly exploiting the local political conflicts. For the Mughal empire that emerged in the 16th century and for other regional rulers, the Portuguese presence did not pose a threat (the military strength of the Mughal emperors was much greater) and an understanding was soon reached. The maritime military superiority of the Portuguese was not given on the mainland and the Portuguese themselves contented themselves with their position as privileged trading masters, with whom regional rulers also cooperated.

With the Casa da Índia , a royal central authority for the administration of overseas territories was created and the Indian trade (not least with pepper and other spices) was strictly controlled. It became the most important economic institution of the Portuguese crown, which for over half a century operated the Indian trade as a state-owned enterprise. The aim of the Portuguese crown was from the beginning to monopolize the pepper and spice trade in Asia in order to prevent the Levant trade. That was extremely ambitious and it soon became apparent that this could not be implemented in real politics with the resources available. Both the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf would have had to be closed, but in the latter case, although the Portuguese controlled Hormuz from 1515 to 1622 , this was never seriously attempted because the Safavid Empire was to be won as an ally against the Ottoman Empire . Buying pepper as cheaply as possible from Indian traders was also unsuccessful, as they now offered the Portuguese pepper of inferior quality, which is why the Portuguese soon increased their purchase sums again. The royal monopoly did not officially fall until 1570; then Portugal concluded contracts with private investors. However, the royal monopoly had already been partially undermined on site. One reason for this was that the funds made available by the Crown for the Portuguese overseas holdings in Asia were insufficient. The interests of the crown and the Portuguese administration in Goa ran contrary to each other.

The local taxation of the spice trade, on the other hand, washed urgently needed money into the coffers of the administration in India and ultimately did not damage the krona, since control and taxation were carried out effectively. The taxation of traders at the various transshipment points, the tariff rate was between 6 and 8%, was soon the most important source of income. Probably the most lucrative was the income from the trading hub of Hormuz. Around 1600 the Estado da India was economically self-sufficient and generated surpluses from trade and local taxation. The Portuguese sold licenses ( called cartaz ) to traders , which allowed them to trade, and brought up merchant ships whose owners did not have them. In contrast, the returning income from exports themselves had less of an impact, at least for the Portuguese administration in India. Administrative posts (headed by a viceroy ) were in great demand because they were lucrative. The Portuguese also functioned as important middlemen in the Chinese trade in the late 16th and early 17th centuries .

European competitors of the Portuguese

The Spaniards concentrated mainly on the New World after the discovery of America and were less active in Asia than the Portuguese. However, they too first tried to control the Moluccas before giving up this claim in the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529. In the research, parallels are sometimes drawn between the reach of the Spaniards in America and that of the Portuguese in Asia (as far as China). The most important Spanish acquisition in Asia was the conquest of the Philippines (1564 to 1572), named in honor of the Spanish King Philip II. After the Portuguese royal family had died out, Philip also became King of Portugal in 1580. However, this only had a limited impact on Portugal's overseas region, as Philip had to make numerous concessions to the Portuguese estates in 1581, including the requirement that only Portuguese officials could continue to be used in the Estado da India and that trade remained in Portuguese hands. It was only a personal union , not a real union , which ended again in 1640.

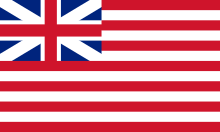

In the course of the 17th century, the Republic of the United Netherlands and the Kingdom of England intervened in the Indian Ocean, especially in the form of trading companies ( East India Companies ). One goal was to push back the Portuguese (or Spanish-Portuguese) influence, but primarily it was about a share in the lucrative Indian trade, which was embedded in the global trade structures of the early modern period. Portugal's influence in the Indian Ocean decreased considerably in the early 17th century for several reasons. The Portuguese military presence in the Estado da India was never too pronounced, whereas the Dutch and English competitors were on the same level in terms of weapons technology and invested considerable resources. In order to counter this, the occasional Portuguese presence was insufficient to effectively secure the spice trade. Furthermore, the structure of the Estado da India loosened up , so that after 1570 the merchants increasingly played an important role, but they could not defend the interests of the Portuguese crown. The competing East India companies, however, were able to mobilize considerable funds due to their financial power as corporations . Less significant European competitors in the Indian Ocean and East Asia were the Danish East India Company (three successive, privileged companies for the Asian trade) and the Swedish East India Company .

The new competition from the Netherlands and England put the Portuguese under increasing pressure, and there were certainly military conflicts (against pirates, among Europeans and against local princes); in addition, the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company (EIC) were mutual rivals. These trading companies represented a new type of actor in the Indian trade and played a dual role in this context.

- “At home they were large commercial enterprises that could bind financially strong economic subjects to themselves and play an important role in the economy and society. In Asia they represented sovereign powers that were not only able to build trade networks but also negotiate treaties and wage wars. "

Both companies endeavored to participate in the spice trade in back India , the political landscape of which was quite fragmented, but the approach differed. The Dutch tried from the beginning to organize a permanent network, while the English company initially organized their trips less systematically. Between 1613 and 1617 there were only 29 ships of the English competition out of 51 voyages by the Dutch.

Since 1619, Batavia was the most important base of the Dutch in rear India, although this was also directed against the English operating in this area. The British attempt to establish themselves in the Malay spice trade ultimately failed due to the military resistance of the Dutch, who were skilful and seriously competed with the Portuguese. The Dutch eventually established a colonial empire ( Dutch East Indies ) with its headquarters in Batavia in this area after they had ousted the Portuguese there in the middle of the 17th century. In the early 17th century they gained control of the eastern Spice Islands, in 1641 they conquered the important Portuguese base of Malacca and in the middle of the 17th century they drove the Portuguese out of Sri Lanka. Portugal and England finally had to withdraw from back India in favor of the Dutch, who also acted with violence against competitors and locals. The English endeavored to get pepper from Sumatra until the end of the 17th century , but ultimately the Dutch were successful here and blocked access.

The Dutch and English also appeared as competitors to Portugal on the Indian subcontinent. In this context, both had sufficient capital to finance their ventures, even though at the beginning the Dutch had better capital resources, which permanently weakened the English East India Company. It was fundamentally reorganized in 1657, but at that time it only had a little more than half of the deposits of its Dutch competitor, plus the initially insufficient political support at home. Both companies also had a sufficiently large military potential not to be eliminated by the Portuguese (as they had done with their Muslim competition at the beginning of the 16th century) and, on the other hand, to exert pressure themselves. The Dutch pursued a dual strategy of trade and military action. Among other things, they were successful in the important Indian textile trade and eventually gained a certain influence at the Mughal court; Furthermore, between 1636 and 1646 they blocked the seasonal trade in Goa with their ships. By 1660 the Dutch, who already had the most developed contemporary economy, largely controlled the cinnamon trade from Sri Lanka and the pepper trade from the Malabar coast. In the following period, however, the importance of the spice trade slowly declined, while the textile and tea trade increased in importance; this applies to both the Dutch and the English.

The English East India Company initially had a difficult time in India, as the rulers of the powerful Mughal empire were initially unwilling to cooperate with the English. Military action against the Mughals would have been futile, as they had a huge army and one of the strongest economic forces in the world at the time. The relationship only slowly changed when, after a long lead-time, the English diplomat Thomas Roe negotiated successfully with the Mughal court in 1616 and received extremely favorable trade and customs conditions for the English East India Company. The English then became involved in the textile trade and received approval for appropriate factories, which in turn competed with the Dutch. In the period that followed, the English East India Company, which had operated as the British East India Company since 1707 , received further privileges for its India business and was also promoted in this regard by the English Crown. From the second half of the 17th century, the company focused primarily on Bengal , which became the core area of the emerging trading empire. Bengal was one of the economically most important regions of India and even the whole of Asia, as it was a great supplier of food (rice, grain, fish, cows and also sugar) and cotton. The profitable cotton and linen trade became the economic cornerstone of the British East India Company, which gained more and more control over the Indian textile industry, with which ultimately neither the Portuguese nor the Dutch could keep up.

The range of goods traded increased over time, including spices and textiles as well as coffee, tea and porcelain. The English East India Company recorded a steady increase in profits in the first half of the 18th century, which was mainly derived from the textile trade (which long surpassed the spice trade in terms of importance) and increasingly from the tea trade. The company operated very successfully in the late 17th and 18th centuries, not only economically but also politically and militarily. Between 1639 and 1690, the company gained control of Madras , Bombay (one of the best ports on India's west coast) and Calcutta .

Now the company began to become increasingly militarized, on the one hand to actively counter Dutch competition and at the same time to assert itself against the Mughal Empire, which went through a phase of weakness in the 18th century. An agreement was reached with the Mughal court in 1717 through diplomatic channels, which took into account the interests of the British East India Company by granting further privileges. The importance of the company on an economic and political level in India increased more and more from the late 17th century. Although the Dutch continued to trade in India, they were never to achieve the political influence that the British East India Company continuously gained, especially in the 18th century. In this context, the British gained increasing territorial control on the Indian subcontinent.

It must be emphasized in this connection that British policy in India was represented almost exclusively by the British East India Company and not, for example, by the British Crown. Over time, the East India Company enjoyed a wealth of power in India that no other business enterprise had before or after; economically, politically and militarily it became the determining power of the subcontinent in the 18th century.

British supremacy in India

The main competitor of the British in India in the mid-18th century was the Kingdom of France. Although the French East India Company, which had been active since the late 17th century, never achieved the importance of the Dutch or English companies (the spice market had long since been divided at this point), the French were also active against the English due to the colonial rivalry in India. In this sense, the French company was subject to strict state supervision. There was considerable tension between England and France, with Joseph François Dupleix , the governor-general of French India , ultimately not being up to his English rival Robert Clive .

The end point of this development was the Seven Years War (1756 to 1763), which was waged globally and also affected India. In principle, the British and French companies were not interested in lengthy and large-scale combat operations in India, as these were very costly and the companies had to generate profits. For this reason, both sides increasingly relied on recruited local mercenaries or levies. On the other hand, successful struggles offered the opportunity for territorial expansion and (this was particularly important here) for the resulting taxation of the new areas.

In June 1757 Clive defeated the Mughal governor of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey , the French themselves could no longer pose a threat to the British. The company profited significantly from the Peace of Paris (1763) , in which France largely forfeited its colonial possessions. Great Britain became the undisputed colonial power, while India was now effectively under British control, although formally a Mughal emperor still sat on the throne in Delhi. This was also no longer a military threat, especially since around 1800 India had around 260,000 local troops under arms (under British officers) and thus had twice as many soldiers as the Royal British Army.

In the middle of the 18th century, the three equal headquarters of the British East India Company Bombay, Madras and Calcutta in Asia were subordinate to around 170 paved and unpaved stations. Over time, the company established a larger and steadily expanding territorial rule in India with direct local administration, something the Portuguese and Dutch, for example, had never seriously attempted in this form. This created a colonial agency and ultimately a British colonial empire in India built up by the East India Company. This was made possible not least by the decline of the Mughal Empire in the 18th century. Following the victory in the Seven Years' War, the British Crown guaranteed the East India Company a quasi-monopoly, which was able to mine raw materials in India, collect taxes and impose economic conditions on the Indians. The great independence of the company led to grievances, destabilized local conditions in India and was oppressive for the locals; the administration was often inefficient and brutal. The company also came under increasing pressure from free British traders after the East India Company lost more and more privileges. The Tea Act of 1773 was intended to give the company freedom to conduct trade in North America, but the company's activities there led to the famous Boston Tea Party .

The tea trade played an increasingly important role for the British East India Company in the 18th century due to steadily increasing demand and was potentially very profitable. Tea was a luxury product that, like pepper and textiles, was very suitable for long-distance trade. The company bought the tea from China (through the port of Canton ), financed with the resources extracted in India. The company in turn shipped tea and raw cotton obtained in India to England. This created a complex, mutually influencing economic system in the context of trade with India and China. This brought in profits, but these were often eaten up again by high costs. Trade with China ultimately even resulted in a negative trade balance to the disadvantage of the British due to Chinese trade restrictions and the limited sales opportunities for British products on the Chinese market . This was the central reason for the smuggling of opium , on which the company had a monopoly, into China, which began in the second half of the 18th century . The opium in China was paid for in silver, which the British in turn used to buy tea (see also China trade ). The Chinese government finally tried to stop the opium trade, which triggered the 1st Opium War from 1839 to 1842. With the peace treaty of 1842 , among other things, the opening of the Chinese market for opium from India was forced.

The company's independent position was already curtailed in the late 18th century ( Pitt's India Act 1784) and was finally lost in the early 19th century. In 1813 it lost its monopoly on trade in India, and in 1834 its monopoly on trade in China. The company lost territorial administration over the Indian possessions after the uprising of 1857 . The company was disbanded in 1858 and the Crown took direct control of India ( British India ).

Trade structures and goods of the Indian trade

In the Indian Ocean, the Europeans encountered a fully developed economic area that stretched from the East African coast to Southeast Asia and whose politically, culturally, religiously and economically heterogeneous regions were linked by sea and inland trade. The political and economic developments were of course very different in the various regions. India, for example, was characterized by the contrast between a largely Muslim-ruled north and a Hindu south, and the respective goods on offer and the markets for regional trade, domestic and sea trade varied. The main transshipment centers were Aden , Hormus and the Indian ports in Gujarat and on the Malabar coast; Malacca was important in Southeast Asia. Local middlemen and money changers played an important role in the long-distance trade networks.

In trade, a distinction must be made between the ongoing Indian merchant shipping (to be separated from domestic trade, which represented a complex economic system of subsistence economy and commercialized trade), whose sales market remained the Asian region around the Indian Ocean with the neighboring areas, and long-distance trade to Europe. In both cases, a significant range of goods were traded from across the Indian Ocean. In the inner-Asian trade, these were for example grain, rice, oil, cotton, manufactured textile products, silk, tea, ivory, metal goods, raw materials, horses and spices, to name just a few examples. The Indian sea trade in the Indian Ocean, which was strongly characterized by cooperation between the various traders, was an important factor in the 16th and 17th centuries, which remained alongside European competition. In this context, luxury goods had a rather small share in the total volume, although they generated high profits. Mainly bulk goods were traded.

India's main export goods in long-distance trade were coarse fabrics (wool and cotton), which were exported to Southeast Asia and the Red Sea region, where they were mainly sold to the poorer classes. In contrast, the European traders initially transported higher quality products (such as silk), which is why there was initially no competition. The Dutch and the English soon became involved in the textile trade (see above), which was to surpass the importance of the spice trade. India also exported large quantities of food, especially grain and rice, which Europeans did not care about. In contrast, the Europeans traded in pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon and other spices which, like textiles, were very suitable for long-distance trade. In addition, there were coffee and sugar as well as porcelain products from the Chinese region and, since the late 17th century, especially tea.

In general, the priorities for export goods from Asia to Europe have shifted over time. Spices initially played a central role, as did textiles for the trading companies, and later tea and coffee. The spice trade, which was so competitive at the beginning, however, tended to lose importance over time. The related percentage shares of the products in the total export from Asia to Europe are very informative.

| product | 1513/19 | 1608/10 |

|---|---|---|

| pepper | 80% | 68% |

| other spices | 18.4% | 10.9% |

| textiles | 0.2% | 7.8% |

| indigo | 0% | 7.7% |

| other goods | 1.4% | 4.6% |

| product | 1619/21 | 1778/80 |

|---|---|---|

| pepper | 56.4% | 11% |

| other spices | 17.6% | 24.4% |

| Textiles and raw silk | 16.1% | 32.7% |

| coffee and tea | 0% | 22.9% |

| other goods | 9.9% | 9% |

| product | 1668/70 | 1758/60 |

|---|---|---|

| pepper | 25.3% | 4.4% |

| textiles | 56.6% | 53.5% |

| Raw silk | 0.6% | 12.3% |

| tea | 0% | 25.3% |

| other goods | 17.5% | 4.5% |

Trade between Asia and Europe fluctuated and was long dependent on the monsoon season , but shipping between Portugal and the Estado da India was already considerable.

- “A total of 1149 ships with a total of 721,705 tons and 330,354 people on board left Lisbon between 1497 and 1700 and 960 ships with 598,390 tons (83.6%) and 292,227 people (88.5%) arrived in Asia. In the opposite direction there were 781 ships with 537,215 tons and 193,937 people, of which 666 with 441,695 tons (85%) and 164,012 people (85.6%) arrived in Lisbon. "

The silver money from Spanish America ( Viceroy New Spain and Viceroyalty Peru ) played an important role in the new global trading system , with which the Europeans paid until well into the 18th century and thus flowed into the early modern world economy.

literature

- Introductory and spanning across eras

- Edward A. Alpers: The Indian Ocean in World History. Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2014.

- Pius Malekandathil: Maritime India. Trade, Religion and Polity in the Indian Ocean. Primus Books, Delhi 2010.

- Roderich Ptak: The maritime silk road. Beck, Munich 2007.

- India trade in ancient times

- Matthew Adam Cobb: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2018.

- Hans-Joachim Drexhage : India trade. In: Der Neue Pauly 5 (1998), Sp. 971-974.

- James Howard-Johnston : The India Trade in Late Antiquity. In: Eberhard Sauer (Ed.): Sasanian Persia. Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2017, pp. 284ff.

- Raoul McLaughlin: The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean. The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India. Pen & Sword, Barnsley 2014.

- Raoul McLaughlin: Rome and the Distant East. Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. Continnuum, London / New York 2010.

- Gary K. Young: Rome's Eastern Trade. Routledge, London / New York 2001.

- India trade in the early modern period

- KN Chaudhuri: The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660-1760. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1978.

- Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Beck, Munich 2014, pp. 370–509.

- William Dalrymple : The Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury Publishing, London a. a. 2019.

- Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498–1620. Magnus, Essen 2005.

- Mark Häberlein : India trade. In: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit 5 (2007), Col. 844-847.

- Jürgen G. Nagel : The adventure of long-distance trading. The East India Companies. 2nd Edition. WBG, Darmstadt 2011.

- Om Prakash: European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998.

- Wolfgang Reinhard : The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Beck, Munich 2016.

Remarks

- ^ Klaus Karttunen: India in Early Greek Literature. Helsinki 1989; Klaus Karttunen: India and the Hellenistic world. Helsinki 1997.

- ↑ Strabo 2: 3 and Periplus Maris Erythraei , chapter 57.

- ^ Lionel Casson: The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Princeton 1989, pp. 21ff.

- ^ Gary K. Young: Rome's Eastern Trade. London / New York 2001, pp. 25ff.

- ^ Matthew Adam Cobb: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE. Leiden / Boston 2018, p. 35ff.

- ↑ On the Silk Road, see Peter Frankopan : Light from the East. Berlin 2016; Valerie Hansen: The Silk Road. A history with documents. Oxford 2016.

- ^ Gary K. Young: Rome's Eastern Trade. London / New York 2001, p. 123ff.

- ↑ On the overland routes between East and West, see Raoul McLaughlin: Rome and the Distant East. Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. London / New York 2010, p. 61ff. See also Matthew Adam Cobb: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE. Leiden / Boston 2018, p. 128ff.

- ↑ See Raoul McLaughlin: Rome and the Distant East. Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. London / New York 2010, pp. 25ff.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 6, 100ff.

- ↑ Strabo 2,5,12.

- ↑ Cf. for example Raoul McLaughlin: The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean. The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India. Barnsley 2014, pp. 88ff.

- ↑ See Gary K. Young: Rome's Eastern Trade. London / New York 2001, p. 22f.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 12, 84.

- ^ Matthew Adam Cobb: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE. Leiden / Boston 2018, p. 274ff.

- ↑ Cf. Monika Schuol: Globalization in antiquity? Sea-based long-distance trade between Rome and India. In: Orbis Terrarum 12, 2014, pp. 273-286; EH Seland: The Indian Ocean and the Globalization of the Ancient World. In: West and East 7, 2008, pp. 67-79.

- ^ Gary K. Young: Rome's Eastern Trade. London / New York 2001, p. 71ff.

- ↑ James Howard-Johnston: The India Trade in Late Antiquity. In: Eberhard Sauer (Ed.): Sasanian Persia. Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh 2017, pp. 284ff.

- ↑ See especially Johannes Preiser-Kapeller: Beyond Rome and Charlemagne. Aspects of global interdependence in long late antiquity, 300–800 AD Vienna 2018, pp. 143ff.

- ↑ Glen Bowersock : The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford 2013, p. 92ff.

- ↑ See James Howard-Johnston: The India Trade in Late Antiquity. In: Eberhard Sauer (Ed.): Sasanian Persia. Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh 2017, here p. 287. On the Roman trade routes and ports on the Red Sea, also Timothy Power: The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate: AD 500–1000. Cairo 2012, p. 19ff.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 443.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here pp. 474–476.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 40f.

- ↑ For the voyages of discovery and their background, see Bailey D. Diffie, George D. Winius: Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415-1580. Minneapolis 1977, pp. 57ff; Malyn Newitt: A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. London / New York 2005.

- ↑ Bailey D. Diffie, George D. Winius: Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415-1580. Minneapolis 1977, pp. 175ff.

- ↑ Michael Kraus, Hans Ottomeyer (Ed.): Novos mundos. New worlds. Portugal and the Age of Discovery. Dresden 2007.

- ↑ See for example Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 472ff .; Roderich Ptak: The maritime silk road. Munich 2007, p. 272ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 113.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005; Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 113ff.

- ↑ Serge Gruzinski : Dragon and feather snake. Europe's reach for America and China in 1519/20. Frankfurt am Main 2014, pp. 48–51.

- ↑ Cf. Serge Gruzinski: Dragon and Feather Snake. Europe's reach for America and China in 1519/20. Frankfurt am Main 2014, pp. 85ff.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, pp. 50–53.

- ↑ See Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498–1620. Essen 2005, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 133f.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, pp. 64–67 and pp. 70–72.

- ↑ Mark Häberlein: India trade. In: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit 5 (2007), Col. 844f.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 67f.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 109f.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 84ff.

- ↑ Serge Gruzinski: Dragon and feather snake. Europe's reach for America and China in 1519/20. Frankfurt am Main 2014.

- ↑ Hugh Thomas: World Without End. Spain, Philip II, and the First Global Empire. London u. a. 2014, p. 241ff.

- ↑ Cf. Friedrich Edelmayer : Philipp II. Biography of a world ruler. Stuttgart 2009, p. 244f.

- ↑ Cf. for the introduction to these companies Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure Fernhandel. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011.

- ↑ See Reinhard Wendt, Jürgen G. Nagel: Southeast Asia and Oceania. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 616.

- ^ Stephan Diller: The Danes in India, Southeast Asia and China (1620-1845). Wiesbaden 1999.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, pp. 138–140.

- ↑ See Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 71ff.

- ^ Quote from Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ See Reinhard Wendt, Jürgen G. Nagel: Southeast Asia and Oceania. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 606ff.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 72.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Reinhard Wendt, Jürgen G. Nagel: Southeast Asia and Oceania. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here pp. 616–620.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 211f.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 497.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498-1620. Essen 2005, p. 43.

- ^ William Dalrymple: The Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. London u. a. 2019; Jürgen G. Nagel: The adventure of long-distance trading. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 77ff.

- ^ KN Chaudhuri: The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660-1760. Cambridge 1978.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, pp. 83ff.

- ↑ General information on development cf. Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 179ff.

- ↑ See Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 80f.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, pp. 119f.

- ^ William Dalrymple: The Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. London u. a. 2019.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 127ff.

- ↑ On the war, see for a comprehensive overview Daniel A. Baugh: The Global Seven Years War, 1754–1763. Britain and France in a great power contest. Harlow 2011; Marian Füssel : The price of fame. A world history of the Seven Years' War. Munich 2019.

- ↑ See Marian Füssel: The price of fame. A world history of the Seven Years' War. Munich 2019, p. 101.

- ↑ On the rule of the British EIC see now William Dalrymple: The Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. London u. a. 2019.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 221.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world. Global history of European expansion 1415–2015. Munich 2016, p. 262ff.

- ↑ For the causes cf. Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here pp. 427–440.

- ↑ See generally Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, pp. 90ff.

- ↑ On the tea trade, cf. KN Chaudhuri: The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660-1760. Cambridge 1978, p. 385ff.

- ↑ Stephen R. Platt: Imperial Twilight. The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age. New York 2018.

- ↑ See Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 441ff .; Peter Feldbauer: The Portuguese in Asia 1498–1620. Essen 2005, p. 32ff .; Pius Malekandathil: Maritime India. Trade, Religion and Polity in the Indian Ocean. Delhi 2010; Roderich Ptak: The maritime silk road. Munich 2007.

- ↑ For a summary of the trade structures in South Asia during the Mughal period, see Stephan Conermann: Südasien und der Indian Ozean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here pp. 481–485.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 476.

- ↑ To summarize, see Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 479f.

- ↑ See Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 444f.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 475f.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 475.

- ^ Jürgen G. Nagel: Adventure long-distance trade. The East India Companies. 2nd edition Darmstadt 2011, p. 14ff.

- ↑ Based on Om Prakash: European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge 1998, p. 36.

- ↑ Based on Om Prakash: European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ Based on Om Prakash: European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge 1998, p. 120.

- ^ Quote from Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 495.

- ^ Stephan Conermann: South Asia and the Indian Ocean. In: Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): History of the world. Empires and oceans 1350–1750. Munich 2014, here p. 494f.