Thomas Müntzer

Thomas Müntzer (also Münzer ; * around 1489 in Stolberg , County of Stolberg ; † May 27, 1525 near Mühlhausen , Free Imperial City ) was a theologian , reformer , printer and revolutionary during the Peasants' War .

As a priest , Müntzer was initially a committed supporter and admirer of Martin Luther . However, his resistance was directed not only against the ecclesiastical authorities ruled by the papacy , but also against the secular order, which was shaped by estates. Because of Müntzer's radical social revolutionary endeavors and his spiritualistic theology, which were reflected in many militant texts and sermons, Luther distanced himself from him at the beginning of the peasant war.

In contrast to Luther, Müntzer stood for the violent liberation of the peasants and was active in Mühlhausen / Thuringia, where he was pastor in the Marienkirche , as an agitator and promoter of the uprisings. There he tried to implement his ideas of a just social order: privileges were revoked, monasteries dissolved, rooms created for the homeless, and a feeder set up. Ultimately, his efforts to unite various Thuringian free farmers as a peasant leader failed because of the strategy of the nobility. He was captured on May 15, 1525 after the Battle of Frankenhausen . The only way for the peasants to escape was the way into the city, where they were slain by mercenaries. Only a few insurgents managed to escape, including Hans Hut . On May 27, 1525, Müntzer was tortured, publicly beheaded and his body impaled.

Life

Origin, studies (1506–1512)

Müntzer was born in Stolberg (Harz) , his exact year of birth is unknown. Before his enrollment at the University of Leipzig in 1506, he had probably lived in Quedlinburg since 1501 . After six years he enrolled at the Brandenburg University of Frankfurt in 1512 . During his studies in Leipzig and Frankfurt an der Oder, Müntzer came into contact with the humanistic world of thought. Precondition for this was the exact command of the Latin language and consequently a good knowledge of various ancient authors. It is not yet possible to prove at which University Müntzer received his Baccalaureus artium , Magister artium and Baccalaureus biblicus titles . After studying theology, his path took him via Aschersleben and Halle to Halberstadt. In Halberstadt he was ordained a priest around 1513/1514 . Because of his simultaneous work as an assistant teacher in Aschersleben and Halle (Saale) , his studies lasted unusually long.

Priest (1513) and preacher (1519–1520)

Around 1513, Müntzer was ordained a priest in the Halberstadt diocese and initially worked at the Michaeliskirche in Braunschweig . Since this office did not cover his livelihood, he took the office of prefect in the canonical monastery Frose near Aschersleben in 1515/16 . There he built a small private school where wealthy citizens' sons were taught.

Between 1517 and 1519 he visited Wittenberg more often . At Easter 1519 he represented the preacher Franz Günther in Jüterbog . Thomas Müntzer probably took part in the Leipzig disputation between Martin Luther and Johann Eck in June 1519 , before going to a Cistercian monastery until 1520. In the same year he was appointed confessor to the Cistercian nuns in the Beuditz monastery near Weißenfels.

Stay in Zwickau (1520–1521)

In May 1520, Müntzer preached on behalf of Johannes Sylvius Egranus in the Marienkirche in Zwickau . When Egranus returned, Müntzer moved to the Katharinenkirche . There in Zwickau, Müntzer now had a large forum that he also used. He was in close contact with Nikolaus Storch , a leading member of the Zwickau prophets . Due to its economic prosperity, Zwickau belonged to the top of the cities in the Electorate of Saxony , it had a Latin and Greek school and, from 1523, a printing press. The supply was u. a. Guaranteed by the Kornmarkt, where the carters offered their grain for three market days before they were allowed to transport it on. The number of inhabitants amounted to six and seven thousand residents around 1520. One of the oldest and also most important trades was cloth weaving.

In the course of the year, Müntzer had problems with the Franciscan order and with his colleague Egranus. When the Zwickau city council suspected him of the riot, he was expelled from the city in 1521. He proudly acknowledged his last pay with “ Thomas Müntzer, qui pro veritate militat in mundo ” (“Thomas Müntzer, who fights for the truth in the world”).

Further changes of location, publications

From Zwickau he went to Bohemia . In Prague he preached on June 23, 1521 in the Bethlehem Chapel ( Betlémská kaple ) and wrote the Prague Manifesto in the city . In November 1521 he left Prague. His next stops were Jena, Erfurt and Weimar. In 1522, Müntzer worked for some time as a chaplain in the St. Georgen Church in Glaucha (today part of Halle ) . Shortly before Easter 1523 he became pastor at the Johanniskirche in Allstedt, Saxony . Here he married the former nun Ottilie von Gersen . A son was born to them on March 27, 1524. During this time he worked on his liturgical reform , the core of which was the translation of the Latin mass texts into German.

On 13 July 1524 he held to Allstedt before the later Elector John the Steadfast and his son John Frederick I , the so-called Prince sermon . In it he called on the Ernestine princes not to offer any resistance to the cause of the Reformation (in the sense of Müntzer). In his speech he attacked the social grievances at the same time, which led to the loss of his position. In April 1524 he set up a print shop in Allstedt, the types came from Wolfgang Stöckel from Leipzig .

Mühlhausen (1524), death

In August 1524 Müntzer finally fled from the authorities of Allstedt to Mühlhausen, where he worked together with the former Cistercian monk Heinrich Pfeiffer . After his expulsion, Müntzer returned to Mühlhausen at the end of February 1525 and was elected pastor of the Marienkirche there. He took the side of the peasants and became their leading figure in the German Peasants' War in Thuringia. On May 15, 1525 he was captured after the battle of Frankenhausen , which ended in a complete defeat of the peasants summoned by Müntzer and in the fortress Heldrungen on the orders of Count Ernst II. Von Mansfeld-Vorderort (1479-1531) in the presence of the Duke George the Bearded tortured. In the tower of Heldrungen incarcerated , he wrote his farewell letter to the insurgents, he thereby calling for the setting of further bloodshed. On Wednesday, May 27th, he was beheaded at the gates of Mühlhausen , his body was impaled and his head was put on a stake.

theology

Concept of faith

Müntzer's theology unites spiritualistic , Anabaptist , apocalyptic and social-revolutionary elements into a unity on a mystical basis .

According to Müntzer, faith means an event initiated by God in the abyss of the soul; it is “the effect of the word that God speaks in the selenium” . Whether such a belief arises depends solely on God, whose spirit blows where he wants ( Jn 3,6 LUT ). The first effect of the word of God in the souls of men is the fear of God, which gives the Holy Spirit a dwelling place and removes everything that opposes the further work of God. These include in particular selfishness and fear of people. The soul that God wants to experience “must first be swept away from worrying and lust” . In this context, Müntzer likes to use the mystical terms langweyl and serenity to describe the state of the empty soul. People who are “boring” and “relaxed” in this sense experience in their depth the work of God and - under pain - the birth of genuine faith, which is no longer afraid of suffering and is at the same time happy. In true faith there is conformity between the human will and that of the crucified Christ . Only such conformity leads to the certainty of belief.

Bible understanding

The Bible primarily bears witness to the experiences that enlightened souls have gained in dealing with the living God. It is an invitation to become open to similar experiences and at the same time a yardstick against which one's own experiences can be measured. The Bible is only the verbum externum (external word), which the verbum internum (internal word) needs to arrive in people. However, the verbum internum does not necessarily need the external word of the Bible to generate faith. According to Müntzer, evidence of this is provided by many people in the Bible who also had no verbum externum when they became believers. It was at this point in particular that the break with Luther occurred.

spiritualism

Not the scribes and - as Müntzer literally says - their book knowledge , but the visionaries are the true interpreters of the Old and New Testaments . Only the godly seer knows God's current will for the present. Only he has the right to proclaim the word of God.

In the Müntzer writings, references to medieval mysticism are unmistakable. There are close relationships with Theologia deutsch and with Johannes Tauler . As a spiritualist, Müntzer rejected infant baptism . True baptism for Müntzer is the baptism of the Spirit ; Water baptism can only take place as a believer's baptism, provided it is the outward sign of an internal process . Those baptized by the Spirit hear the voice of the exalted Christ and " see Him walking on the waters of their souls diepe ". For Müntzer, the outer baptismal water is only the symbol for the movement that God works in our soul.

Apocalyptic

The prophetic books of the Bible, especially Daniel , and the Revelation of John were particularly valued by Müntzer. His visionary interpretation of the apocalyptic parts of the Bible led him to see the Roman Catholic Church in the purple- clad whore of Babylon ( Rev 17.4 LUT ; 18.16 LUT ) . He simply included Luther and syn appendix here. In the prince's sermon , in which he interprets the second chapter of the book of Daniel, he interprets the four world empires of the Apocalypse on the empires of the Babylonians, Persians, Greeks and Romans. He calls his time the fifth rich , which is also made of iron because it suppresses the poor and the innocent. Therefore a new prophet Daniel is needed. In other places he calls on all godly people to expect a new Baptist John . Most of all, however, he likes to talk about a new Elijah who has to come in order to organize the world in God's will. In his opinion, this also included the killing of the Baalspfaffen (= office holders of the old church loyal to the Pope ) and the overthrow of the godless political rulers.

"Theology of the Revolution"

In an apocalyptic view, Müntzer interpreted his time as the dawn of the divine judgment. Wheat is to be separated from weeds; the word of Jesus applies: "I did not come to bring peace, but the sword" ( Mt 10,34 LUT ). With reference to 2 Mos 22,1ff LUT he calls out to the assembled sovereigns: "A godless person has no right to live where he hinders the pious [...] as we eat and drink food, so is the sword, to destroy the wicked. ”Jesus was born in a cattle shed; he was on the side of the poor and the oppressed. Those who dress in fur coats and sit on silk pillows are "Christ ain abomination".

Müntzer had a good eye for the social problems of his day. His socio-ethical interests are in close contact with his mystical and theological ideas. Müntzer was not only zealous for the fear of God, but as a God-fearing man for social justice.

Liturgy and church music

Thomas Müntzer's liturgical reforms, which he launched in his capacity as pastor in Allstedt in 1523 and 1524 with two publications (“Allstedter Kirchenampt” and “Deutzsch-Euangelisch Mesze”), are an example of the Reformation search for an appropriate one Protestant form of worship of importance. Just like his hymns , this part of Müntzer's work continued beyond his death. His German church services, in which he wanted to make the Latin Mass and the Latin Liturgy of the Hours usable for the German-language Protestant worship service with only careful and careful changes , were used for many decades in some parts of Saxony and Thuringia and reprinted several times - but always without the mention from Müntzer's name.

Müntzer's liturgical publications attempt to translate the Latin church chants (late medieval Gregorian chant ) introduced in Allstedt relatively directly into German. This made Müntzer one of the pioneers of German-language church services in Central Germany - his impatience to translate Reformation ideas into popular church work is evident and was shaped by enormous success in Allstedt. Martin Luther and his entourage observed Müntzer's liturgical reforms with skepticism, whereby the skepticism was based less on liturgical and theological concerns than on the enormous concern about the popularity that the little diplomatic reformer Müntzer thus achieved.

It must be assumed that Luther's decision to base his “ Deutsche Messe ” in 1526, unlike his liturgical publications in 1523 and 1524, on German-language songs and no longer on Gregorian chant as an essential hymn element, was a deliberate demarcation from Müntzer shows, after the events of 1525 (suppression of the Thuringian peasant uprising) it had become clear how easily the Reformation could be politically instrumentalized and the danger that the theological concerns of the Reformation stood in the wake of social conflicts. Luther's judgment on Müntzer's liturgical reforms (“imitating as the monkeys do”) fits in with a massive rejection of Müntzer that appears again and again in his table speeches. Some of Müntzer's songs are still printed in Protestant and Catholic hymn books (e.g. the hymn transmission EG 3 " God, holy creator of all stars ").

Commemoration

At Allstedt Castle is under the title “Thomas Müntzer. A Servant of God ”to see a permanent exhibition on his life and work. In Mühlhausen, a peasant war museum also commemorates Müntzer and the battles against feudal rule at the time; there is also a Müntzer memorial in the Marienkirche.

The Thomas Müntzer Society , founded in 2001, deals with the life and work of Thomas Müntzer and his relationship to the Reformation and the Peasants' War, as well as the history of reception.

Friedrich Wolf wrote a play by Thomas Müntzer .

The DEFA film Thomas Müntzer - A Film of German History was released in 1956.

The proletarian passion of the Austrian political rock group Butterflies , published for the first time in October 1977 , contains in section 2 a report on Thomas Müntzer as well as on the events in connection with the peasant wars up to the battle of Frankenhausen .

The play Martin Luther & Thomas Munzer or the introduction of the accounting of the left-wing intellectual author Dieter Forte was founded in 1984 at the People's Theater in Rostock from the GDR television recorded. Thomas Müntzer plays an important role in this Luther film .

Another DEFA film Ich, Thomas Müntzer, Sichel Gottes was released in 1989.

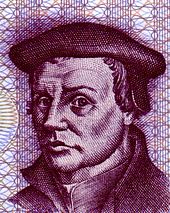

Müntzer was depicted on the GDR 5-mark banknote valid from 1971 to 1990 . In 1989 the State Bank of the GDR issued a 20-mark commemorative coin with a portrait of Müntzer. The "Thomas Müntzer Medal" was the highest award of the Association of Mutual Peasant Aid in the GDR.

In memory of the early social revolutionary Müntzer, Werner Tübke created the Peasant War Panorama near Bad Frankenhausen from 1976 to 1987 (actual title: “Early bourgeois revolution in Germany”).

Thomas Müntzer is one of the main characters in the novel Q by Luther Blissett (pseudonym of an anonymous Italian collective of authors). The recent German literature has rediscovered Muentzer as an object, such as Hendrik Jackson with his poetry collection roaring Bulgen (2004) and Frank Fischer with his travel narrative The Südharz Travel (2010).

Names and monuments

The place of birth Stolberg and the place of death Mühlhausen were given the official name affix “Thomas-Müntzer-Stadt” (Mühlhausen 1975 on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of death). After German reunification in 1989/1990, the surnames were deleted in contrast to the "Luther cities" of Eisleben and Wittenberg.

In Kapellendorf the local Protestant parish named their meeting place "Evangelical Community Center Thomas Müntzer" and had a statue of Müntzer erected there in 1989.

In numerous places there are streets and squares that are named after Müntzer, for example in Berlin, Rostock, Dresden, Halle (Saale), Weimar, Nordhausen, Mühlhausen, Sömmerda, Halberstadt and Ravenstein. A street in Vienna- Favoriten is also named after him (in the spelling Thomas-Münzer-Gasse ). The now closed copper mine in Sangerhausen was opened up via the Thomas Müntzer shaft.

From 1953 to 1990 the theater in Eisleben was called the Thomas-Müntzer-Theater .

Schools in many places in Central Germany bear his name, including in Mühlhausen, Magdeburg, Sangerhausen, Güstrow, Wernigerode, Allstedt and numerous smaller communities. A listed integrative day-care center in Radebeul is named after Müntzer.

On February 20, 1989, a portrait bust of Thomas Müntzer, created by the sculptor Christine Dewerny, was installed in the building of the former St. Maria-Victoria-Heilanstalt in Berlin.

The "Thomas-Müntzer-Scheuer" is located on the grounds of the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart.

Müntzer's day of remembrance is May 27th (not included in the official evangelical name calendar ).

The Peasant War Panorama by the artist Werner Tübke was opened in 1989 on the historic Schlachtberg in Bad Frankenhausen . In addition to biblical themes, this circular painting also shows the devastating peasant war and Müntzer and Luther.

Memorial plaque on house Niedergasse 2 in Stolberg (Harz)

Inscription above the front door at Niedergasse 2 in Stolberg (Harz)

Memorial plaque on the house at Schloßstraße 26, in Lutherstadt Wittenberg

A memorial plaque on the town hall in Heilbad Heiligenstadt

Fonts

- Prague Manifesto (1521)

- Three liturgical writings (1523)

- German Church Office

- German Evangelical Mass

- Order and calculation of the German Office in Allstedt

- From the poetic faith (early 1524)

- Protestation or Surrender (early 1524)

- Interpretation of the second chapter of Daniel (so-called prince sermon ) (July 1524)

- Expressed exposure [of false belief] (summer 1524)

- Highly caused protective speech (autumn 1524) mlwerke.de

Around 95 German and Latin letters have survived.

expenditure

- Günther Franz , Paul Kirn (ed.): Thomas Müntzers writings and letters. Critical complete edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1968.

- Gerhard Wehr (Ed.): Thomas Müntzer; Writings and letters . Diogenes, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-257-21809-5 .

- Helmar Junghans (Ed.): Thomas Müntzer Edition. Critical complete edition . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2004 ff.

- Writings and Fragments . 2017, ISBN 978-3-374-02202-1 .

- Correspondence . 2011, ISBN 978-3-374-02203-8 .

- Sources for Thomas Müntzer . 2004, ISBN 3-374-02180-8 .

literature

- Alfred Meusel : Thomas Müntzer and his time. With a selection of the documents from the great German Peasant War . Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1952

- Ernst Bloch : Thomas Münzer as the theologian of the revolution. Reclam, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-379-00436-7 (first published in 1921).

- Thomas Nipperdey : Theology and Revolution with Thomas Müntzer. In: Archive for the history of the Reformation . 54, 1963, pp. 145-181.

- Walter Elliger : Thomas Müntzer. Life and work. 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1976, ISBN 3-525-55318-8 .

- Hans Pfeiffer : Thomas Müntzer. A biographical novel. New life, Berlin 1981.

- Alfred Stern : Müntzer, Thomas . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1886, pp. 41-46.

- Eike Wolgast : Thomas Müntzer. A disturber of the unbelievers. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-374-00467-9 .

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz : Thomas Müntzer. Mystic - apocalyptic - revolutionary. Beck, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-33612-4 .

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Thomas Müntzer. Revolutionary at the end of time. A biography . Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68163-9 (completely revised and partly rewritten new edition of his book from 1989).

- Gerhard Brendler : Thomas Müntzer - Spirit and Faust. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-326-00475-3 .

- Günter Vogler : Thomas Müntzer. Dietz, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-320-01337-8 .

- Klaus Ebert (ed.): Thomas Müntzer in the judgment of history. From Martin Luther to Ernst Bloch. Hammer, Wuppertal 1990, ISBN 3-87294-417-7 .

- Daniel Heinz: MÜNTZER (Münzer), Thomas. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 6, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-044-1 , Sp. 329-345.

- Horst Herrmann : Thomas Müntzer today. Attempt over a repressed. Klemm & Oelschläger, Ulm 1995, ISBN 3-9802739-7-0 .

- Günter Vogler: Müntzer, Thomas. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-00199-0 , pp. 547-550 ( digitized version ).

- Tobias Quilisch: The right of resistance and the idea of the religious covenant with Thomas Müntzer - a contribution to political theology. Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-09717-3 (also dissertation at the University of Freiburg (Breisgau) 1998).

- Arnulf Zitelmann : I want to thunder over them. The life story of Thomas Müntzer. Beltz & Gelberg, Weinheim 1999, ISBN 3-407-78794-4 .

- Wolfgang Ullmann : Ordo rerum. The Thomas Müntzer Studies. Context, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-931337-43-X .

- Jan Cattepoel: Thomas Müntzer. A mystic as a terrorist. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56476-9 .

- Marion Dammaschke, Günter Vogler: Thomas-Müntzer-Bibliography (1519–2012). Baden-Baden: Koerner 2013. ISBN 978-3-87320-733-2 .

- Ulrike Strerath-Bolz: Thomas Müntzer. Why the mystic led the peasants to war. A portrait. Wichern-Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-88981-375-6 .

- Siegfried Bräuer; Günter Vogler: Thomas Müntzer. To restore order in the world. A biography. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2016, ISBN 978-3-579-08229-5 .

- Thomas-Müntzer-Gesellschaft , publications No. 1 to 10.

- Günter Brakelmann : Müntzer and Luther. Luther-Verlag, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-7858-0691-3 .

- District of Mansfeld-Südharz , State Center for Political Education of the State of Saxony-Anhalt (Ed.): Müntzer. Not a side note to the story. Publisher Janos Stekovics, Wettin-Löbejün 2017, ISBN 978-3-89923-378-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Thomas Müntzer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Thomas Müntzer in the German Digital Library

- Thomas-Müntzer-Society e. V.

- private page with texts by Thomas Müntzer

- private page find failed: Thomas Müntzer

- Jürgen Müller: Martin Luther & Thomas Müntzer. Their lives and times as well as their Reformation effects on the events of the German Peasants' War from 1524–1525. University of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main March 1, 2013, uni-frankfurt.de (PDF)

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Goertz : Thomas Müntzer. Mystic - apocalyptic - revolutionary. Beck, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-33612-4 , p. 15f. It says: “Nobody knows what Thomas Müntzer looked like. There is no contemporary portrait of him. (...) The famous copper engraving, behind which a realistic copy of a contemporary was sometimes suspected, comes from a heretic gallery of the 17th century. "

- ↑ Helmut Bräuer: Zwickau at the time of Thomas Müntzer and the peasant war. Sächsische Heimatblätter 20 (1974), pp. 193-223.

- ↑ Helga Schnabel-Schüle : Reformation. Historical and cultural studies manual. Metzler, Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-476-02593-7 , p. 105.

- ↑ cf. Otto Zierer : Picture of the Centuries . Bertelsmann-Verlag, undated, Volume 14, p. 177.

- ↑ Peter Michel: Germany as a cultural nation? With documentary images. Heinen, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-95514-003-8 , p. 41.

- ↑ Thomas-Müntzer-Scheuer (TMS) .

- ↑ Thomas Müntzer. In: Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints .

- ^ Gerhard Wehr (ed.): Thomas Müntzer; Writings and letters . Diogenes, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-257-21809-5 , p. 7.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Müntzer, Thomas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Protestant theologian and revolutionary during the peasant war |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1489 or 1490 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stolberg (Harz) |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 27, 1525 |

| Place of death | Mühlhausen / Thuringia |