revolution

A revolution is a fundamental and lasting structural change in one or more systems that usually occurs abruptly or in a relatively short time. It can be peaceful or violent. There are revolutions in the most varied areas of social and cultural life. The terms evolution and reform are antonyms : they stand for slower developments or for changes without radical change. The exact definition is controversial; there is no generally valid theory of revolution about the necessary and sufficient conditions for the emergence of every revolution, the phases of its course and its short-term and long-term consequences. A person involved in a revolution is called a revolutionary .

term

Word origin and concept development

The foreign word revolution was borrowed in the 15th century from the late Latin revolutio ("rotation", literally "rolling back") and initially referred to as a technical term in astronomy the orbit of the celestial bodies . Nicolaus Copernicus used the Latin word revolutio with this meaning in his main work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543).

In England in the 17th century, the term was used in relation to the Glorious Revolution in 1688 in the sense of a restoration of the old legitimate state (a rolling back of social relations). Today's main meaning of violent political overthrow came, starting from the French révolution ., In the 18th century. In the history of the GDR , for example, a very special interpretation emerged with the term early bourgeois revolution .

Main meaning

The term revolution is used today for profound changes in the most diverse areas, for example in science , culture , fashion , etc. Today, political or social revolutions are critical transformation processes in which the legal or constitutional decision-making process is overridden and the until then the ruling elite is deposed and a different political system with different representatives is installed.

A real definition is not available because of the diversity of the many processes described as revolution. For example, it is controversial whether a revolution must necessarily come from below, that is , must be supported by an underprivileged social group or class , whether revolutions must always be violent , or whether unsuccessful, i.e. suppressed, attempts at revolution are to be described as or to be distinguished from them as revolts or uprisings . The historian Reinhart Koselleck complained in 1984 that the term was so "worn out" by its ubiquitous use that it needed a precise and verifiable definition in order to continue to be used, "if only to find consensus on the dissent" .

Typology

Revolutions can be classified according to various criteria. There is a widespread distinction between supporting strata, whose interests are to be enforced in the revolution: civil revolutions are identified (such as the Glorious Revolution 1688 or the French Revolution ), proletarian (such as the October Revolution 1917) and agrarian revolutions such as the Mexican Revolution , the Chinese revolution and various wars of independence in the process of decolonization after World War II . The political scientist Iring Fetscher also calls the "intellectual" or "managerial revolution".

Another classification criterion is the ideology of the protagonists of the revolutionary movement: According to this, a distinction must be made between democratic , socialist and fascist revolutions. Revolutions can also be classified according to their causes, whereby exogenous factors (e.g. wars and economic dependencies) and endogenous factors (dissatisfaction of the population, modernization processes and their sometimes negative consequences - such as pauperism at the beginning of the industrial age - change in values and Ideologies that are shared among the population, etc.).

The political scientist Samuel P. Huntington distinguishes between revolutions of the western and the eastern type: Those like the French or the Russian revolutions would take place in weak traditional regimes that visibly disintegrated in a crisis . Therefore, only a small amount of violence is required to overthrow them. Subsequently, the argument between moderate and radical revolutionaries is more violent. During this struggle, the revolution spread from the metropolis in which it originated to the rural population. On the other hand, revolutions of the Eastern type would arise in colonized areas or military dictatorships : Since these regimes are strong, they came from guerrillas who operated in rural areas, from where they conquered the capital with considerable efforts of violence up to civil war . Examples of Eastern revolutions are the Chinese Revolution and the Vietnam War . The political scientist Robert H. Dix added the Latin American type, in which an urban guerrilla allies with urban elites and thus overthrows the old regime.

Theories of revolution

In the world of ideas of traditional pre-industrial societies, which were based on a harmonious order, a harmony of man , society and nature with the divine creation , the community , individual groups and also the individual person were threatened by the corruptio (corruption) that always existed is when an order ( form of government ) loses its positive features, such as when free citizens are unilaterally dependent on others, and when doing the virtue (virtus) is lost, the own well with the common good is to unite. In such a situation it is advisable to return to the starting point ( Machiavelli : Ritorno ai principi ), to bring disorder back into order. In fact, right up to modern times , revolutionary movements right up to the beginnings of the French Revolution consistently made the initial demand to return to the “old law”. It was only after the revolution of 1789 that the idea that a “revolution” in today's sense would create something new took hold.

Sociological concept of revolution

In sociology and colloquially, a “revolution” denotes a radical and mostly, but not always, violent social change (overthrow) in existing political and social conditions. If necessary, this can lead to an upheaval in the cultural “norm system of a society”. A revolution is either carried by an organized, possibly secret, group of innovators (cf. avant-garde , elite ) and is supported by large sections of the population, or it is a mass movement from the outset .

Partly the term emancipation is added, i. H. the idea of liberation from grown structures and a gain in social or political freedom for the individual. The importance of the individual criteria for defining a revolution is quite controversial.

If, without profound (radical) social change, only a small organization or a closely linked social network with a relatively small mass base undertakes a violent overthrow, this is known as a coup d'état or, especially with the participation of the military , a coup. After successful coups, the term revolution is then often used as an ideological justification by reinterpreting the coup as a revolution. Putsches can also trigger profound transformation processes in the sense of a revolution, the transition between the two terms is fluid.

Sometimes the term revolution is also used to denote a more general, profound change in the structure of society, even if it is not necessarily one of particularly sudden and rapid changes. We are talking about the Neolithic Revolution - which lasted several thousand years globally - or the Industrial Revolution that spread from England across the European continent between 1750 and 1850 , which in turn was a precondition for various political revolutions during this period.

An example of a sociological theory of revolution is the Marxism , the only endogenous, namely economic causes of revolutions assumes: The intrinsically dynamic, dialectical development of productive forces would class antagonisms exacerbate such that a proletarian world revolution with scientific safety would result. This prognosis turned out to be erroneous.

Political science concept of revolution

The political science has been unable to agree on a unified theory of revolution. The historian Eberhard Weis, for example, names five main factors that represent essential prerequisites for the emergence of a revolution, whereby he does not take developing countries into account:

- A sudden recession

- after a period of economic prosperity, increasing prosperity and increasing expectations for the future or

- after a natural disaster ;

- a public opinion that challenges the existing institutions;

- the solidarity of various groups in society who have different reasons for being dissatisfied with the existing situation and who are temporarily joining forces to overthrow the old order;

- an ideology;

- Weakness, disagreement and inefficiency on the part of the opposing forces, the state.

The American sociologist Charles Tilly sees a “revolutionary situation” as the prerequisite for every revolution, which he defines as “a forcefully forced relocation of state power”: Two power blocs are irreconcilably opposed to one another , both of which lay claim to sovereignty in the state. In this respect, a revolution is "an escalated form of the normal pluralistic struggle of social groups for the distribution of the values of domination, security and welfare that go beyond the legal framework of the political system". The decisive factor for the success of the revolutionary group is not so much how great the general dissatisfaction is, but how well and how sustainably it succeeds in using this to mobilize larger parts of the population and to form coalitions. If this succeeds and if the holders of state power prove to be incapable of suppressing or reintegrating the groups in opposition to them, the tension will discharge in one or more “revolutionary events”: There will be violence and the revolutionary group can possibly enforce their claim to power.

Revolution in constitutional law (revolutionary law)

The concept of "revolutionary law" in Germany goes back to Johann Gottlieb Fichte's philosophical considerations on the French Revolution (1793). As a result of the November Revolution in the Weimar Republic, the law of the revolution developed in the civil law jurisdiction of the Reichsgericht , which was also constitutionally recognized and adopted by the State Court in 1926 :

“The Reichsgericht has consistently taken the position that in state life actual rule, which has been able to assert itself against resistance, has legal recognition. In particular, the state authority newly created by the upheaval was not denied state recognition. The illegality of their reasoning was not considered to be an obstacle because the legality of the reasoning is not an essential feature of state authority […]. The so-called right of revolution has thus been recognized. "

This jurisprudence and the associated way of thinking later legitimized the Nazis' seizure of power . The normative power of revolutionary law was confirmed again in 1952 by the Federal Court of Justice .

Theorists and practitioners of the revolution

Sociological theorists of the revolution

(See also the catalog raisonnés in the personal articles.)

- Vilfredo Pareto ("Revolution" as a special form of elite replacement)

- Max Weber (in Europe / North America capitalism initially required a radical non-economic - religious - change in mentality, namely in the form of Protestantism )

- Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (the European revolutions as a series of articles revolutions , starting with the "papal revolution" of the papacy against the medieval empire and ending with the " proletarian revolution")

- Pitirim Sorokin (sociological typology)

- Crane Brinton (socio-historical type formation)

- Ralf Dahrendorf ("Revolution" as (1) radical and (2) rapid social change , caused by (1) intense or (2) violent social conflicts )

- Theda Skocpol (sustainable revolutions are mainly peasant revolutions)

Theoretically arguing revolutionaries

- Karl Marx (every society in which a form of ownership of the means of production allows human labor to subordinate itself inevitably ends in revolution or ruin; a distinction must be made between “revolutions of the productive forces ” and the “revolutions of the relations of production” triggered by them).

- Friedrich Engels (Work and its domination through property triggered the first revolution after early communism , which replaced “savagery” with barbarism and was the beginning of history , and work and property will be optimally arranged through the last revolution - the world revolution in which the end of the “realm of necessity” and the beginning of the “realm of freedom ” will be possible).

- Rosa Luxemburg ( imperialism is capitalism's last means of defense before the final worldwide proletarian revolution - in alliance with the proletariat of the colonial powers).

- Lenin (by building a cadre party of professional revolutionaries, even if the proletariat is still a minority, the revolution in the relations of production can be brought forward - see also Revolutionary Situation ).

- Anton Pannekoek (parties and trade unions - including the Leninist - are unsuitable forms for the struggle of the working class for their emancipation, everything depends on the self-organization of the workers).

As well as (alphabetically) Bakunin , Bolívar , Danton , Debord , Guevara , Ho Chi Minh , Mao Zedong , Marat , Mazzini , Nkrumah , Robespierre , Saint-Just , Shariati , Torres , Trotsky and other revolutionaries of the 18th to 20th centuries.

Examples

Systems of rule and politics

Revolutions "from below":

- The uprisings known as the Peasant Wars, which flared up again and again in Europe from the 14th century to the 19th century, were regularly and bloodily suppressed. In the Marxist view of history, the German Peasants' War 1524–1526 in particular is referred to as the " early bourgeois revolution ".

- The first revolution to be described as the "Revolution" was the Emden Revolution of 1595 in East Frisia .

- Glorious Revolution in 1688 in England , the rule of the Stuarts ended

- American Revolution 1776-1781, often called American War of Independence referred

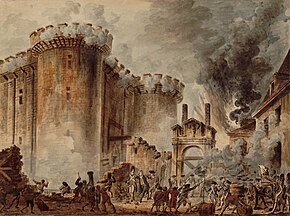

- French Revolution 1789–1799

- Haitian Revolution 1791–1804

- the failed revolution of 1848/1849 in several European countries

- Russian Revolutions 1917: February Revolution and October Revolution . The terms putsch or coup d'état are sometimes used today for the October Revolution .

- November Revolution in Germany 1918/1919, including the council republics in Bavaria ( Munich council republic ) and Bremen ( Bremen council republic ) as well as some in the Ruhr area

- the National Socialist seizure of power . The use of the concept of revolution is controversial in this case.

- the Cuban Revolution 1953–1959

- Islamic Revolution in Iran 1979 and the subsequent measures to reorganize the state, economy and society

- The 1979 Nicaraguan Revolution , after the Cuban Revolution, the second successful Latin American Revolution in the Cold War

- The peaceful revolution in the GDR 1989/1990

Revolutions "from above":

- Meiji Restoration , renewal of imperial power in Japan from 1868

- White Revolution , Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's reform program in Iran (1963)

- Cultural Revolution , a series of campaigns in the People's Republic of China 1966-1976, with the aim to eliminate capitalist and traditional elements of culture and society and the dominance of Maoist orthodoxy in the CCP hedge

Society, technology, science

- Neolithic Revolution , the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and cattle breeding (transition to the Neolithic Age , approx. 15,000 BC)

- Industrial revolution , the transition from an agrarian society to an industrial society since the second half of the 18th century.

- Scientific revolutions, e.g. B. the sequencing ("decoding") of the human genome as a biological revolution . See also paradigm shift .

- Sexual revolution in the second half of the 20th century, which overturned traditional moral concepts.

- Green revolution , the development of high-yielding agricultural varieties and their spread in the Third World from the late 1960s.

- Electronic or digital revolution from around 1980.

literature

- Gunnar Hindrichs : Philosophy of Revolution . Suhrkamp: Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-518-58707-2 .

- Florian Grosser: Theories of the Revolution as an introduction . Junius: Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-88506-075-8 .

- Immanuel Ness (Ed.): The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present. Wiley & Sons, Malden, MA et al. a. 2009, ISBN 978-1-4051-8464-9 .

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels : The Communist Manifesto . A modern edition. With an introduction by Eric Hobsbawm. Argument-Verlag, Hamburg, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-88619-322-5 .

- Charles Tilly : The European Revolutions . CH Beck, 1993, ISBN 978-3-406-37703-7 .

- H.-W. Krumwiede, B. Thibaut: Revolution - revolution theories. In: Dieter Nohlen (Hrsg.): Dictionary State and Politics. Piper, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11179-3 , p. 593 ff.

- Kurt Lenk : Theories of the Revolution . UTB, 1981, ISBN 3-7705-0795-9 .

- Hannah Arendt : About the revolution . Munich 1963, ISBN 3-492-11746-5 .

- Eric Hobsbawm : European Revolutions 1789 to 1848 . Zurich 1962. (Reprint: Parkland-Verlag, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-89340-061-3 )

- Pitirim Sorokin : Sociology of revolution. (German: The Sociology of Revolution. Lehmann, Munich 1928, DNB 368435768 )

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Cordula Koepcke: Revolution. Causes and effects. Günter Olzog Verlag, Munich 1971, p. 16.

- ↑ Duden: The dictionary of origin. 3rd edition 2001, p. 673.

- ↑ Ines Jachomowski: Peasants' War and Early Bourgeois Revolution in the historical image of the GDR , GRIN Verlag, 2007 ISBN 9783638801041

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Widmaier : Revolution / Revolutionstheorien. In: Everhard Holtmann (Ed.): Political Lexicon . 3rd edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-486-79886-9 , p. 607 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Reinhart Koselleck: Revolution. In: the same, Otto Brunner , Werner Conze (eds.): Basic historical concepts . Historical lexicon on political and social language in Germany. Volume 5, Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart, p. 788 f.

- ^ Iring Fetscher: Evolution, Revolution, Reform. In: derselbe and Herfried Münkler (Ed.): Political Science. Concepts - analyzes - theories. A basic course. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1985, pp. 399 - 431, quoted from Ulrich Weiß : Revolution / Revolutionstheorien. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 7: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 561.

- ^ Ulrich Widmaier: Revolution / Theories of Revolution. In: Everhard Holtmann (Ed.): Political Lexicon . 3rd edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-486-79886-9 , pp. 607 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Ulrich Weiß: Revolution / Revolutionstheorien. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 7: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 563.

- ^ Samuel P. Huntington: Political Order in Changing Societies. Yale University Press, New Haven 1969, quoted from Robert H. Dix: The Varieties of Revolution. In: Comparative Politics 15, No. 3: 281 (1983); Dieter Wolf and Michael Zürn : Theories of Revolution. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 1: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 554 f.

- ^ Robert H. Dix: The Varieties of Revolution. In: Comparative Politics 15, No. 3: 281-294 (1983); Dieter Wolf and Michael Zürn: Theories of Revolution. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 1: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 554.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner quotes in the story of a German a legal definition that revolution is "the change of a constitution with other than the means provided in it", which, in his own opinion, does not accurately describe the facts.

- ↑ H.-W. Kumwiede, B. Thibaut: Revolution - Revolution theories . In: Dieter Nohlen (Hrsg.): Dictionary State and Politics. Piper, Munich 1991, p. 593 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Widmaier: Revolution / Theories of Revolution. In: Everhard Holtmann (Ed.): Political Lexicon . 3rd edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-486-79886-9 , p. 608 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Ulrich Weiß: Revolution / Revolutionstheorien. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 7: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 563.

- ^ Iring Fetscher: From Marx to the Soviet ideology. Presentation, criticism and documentation of Soviet, Yugoslav and Chinese Marxism. Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Munich 1972, p. 39 ff.

- ↑ After: Eberhard Weis, Der Durchbruch des Bürgerertums. 1776-1847 . Propylaea History of Europe, Vol. 4, Berlin 1978, p. 96 f.

- ^ Charles Tilly: The European Revolution. CH Beck, Munich 1993, p. 25 (here the first quote) and passim; Dieter Wolf and Michael Zürn : Theories of Revolution. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics. Volume 1: Political Terms. Directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 561 ff (here the second quote).

- ↑ RGZ, 100, 25; see. previously: RGSt 53, 65.

- ↑ Decision of October 16, 1926 in RGZ 114, Appendix, p. 1 ff. (6 ff.)

- ↑ Judgment of February 8, 1952 (V ZR 6/50) in BGHZ 5, p. 76 ff. (P. 96).

- ^ Josef Foschepoth : Reformation and Peasants' War in the GDR's historical image. On the methodology of a changed understanding of history . Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1976, passim.

- ^ Dietrich Geyer : The Russian Revolution. 4th edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985, p. 106; Armin Pfahl-Traughber: Forms of Government in the 20th Century. I: Dictatorial Systems. In: Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse (Hrsg.): Staatsformen. Models of political order from antiquity to the present. A manual. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, p. 230; Gerd Koenen : The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 750; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 58; Manfred Hildermeier : The Russian Revolution and its Consequences. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 34–36 (2017), p. 13 ( online , accessed on June 18, 2019).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society . Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, SS 601 f. and 619 ff.

- ^ Horst Möller : The National Socialist seizure of power. Counterrevolution or Revolution? (1983) [1] at ifz.muenchen.de

- ↑ Hans Joachim Winckelmann: Who completes the biological revolution? In: Dominik Groß , Monika Reininger: Medicine in History, Philology and Ethnology: Festschrift for Gundolf Keil. Königshausen & Neumann, 2003, ISBN 978-3-8260-2176-3 , pp. 203-227.