Latin America

Latin America ( Spanish América Latina or Latinoamérica , Portuguese América Latina , French Amérique latine ) is a political-cultural term that serves to differentiate the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries of America from the English-speaking countries of America (→ Angloamerica ). In today's usual definition of the term, Latin America only includes those countries in which Spanish or Portuguese predominates. These include Mexico , Central America (excludingBelize ), the Spanish-speaking areas of the Caribbean and the countries of South America (excluding Guyana , Suriname and French Guiana ). The countries of Latin America together cover an area of around 20 million km² and the population is around 650 million people. (Status: 2019)

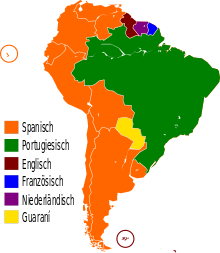

The Latin part refers to Latin as the origin of the Romance languages . In the literal sense, countries and areas in which French is spoken also belong to Latin America (see map on the right). However, this understanding has not become generally accepted in the German-speaking area. There are also other different definitions (see below).

Latin American countries

In a narrower sense, those countries belong to Latin America in which Spanish or - with regard to Brazil - Portuguese dominates. In multilingual Paraguay , the two official languages Guaraní and Spanish are roughly equivalent and are understood by most of the locals; in a broader sense, French-speaking countries and territories are also often included.

Extended and different definitions

- In the literal sense, Latin America also includes all French-speaking areas of America (and the Caribbean), which is also defined in the United States . According to this definition, the French-speaking Canadian province of Québec would theoretically also be part of Latin America. However, Québec is located in the middle of Anglo-America and is so closely intertwined with the Anglo-American cultural area that Québec is not counted as part of Latin America - neither is it part of Anglo-America because Québec is not English-speaking. The same applies to the Cajuns in Louisiana .

- Despite its French official language, Haiti has closer ties to the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries than other Caribbean countries due to its shared history and the national border with the Dominican Republic. For this reason, it is sometimes included in Latin America even when the other French countries and territories are not included.

- Taking into account that in the Dutch areas of Aruba , Bonaire and Curacao Papiamento , a Creole language with partly Romance roots, is spoken, some of these countries are included in the definition of Latin America.

- From the point of view of colonial history , the entire Caribbean is sometimes included in Latin America. In statistics of international organizations, however, it is usually shown separately ( Latin America and the Caribbean ).

- According to another definition used now and then in the USA, Latin America refers to all American states south of the United States, including Belize, Jamaica , Barbados , Trinidad and Tobago , Guyana, Suriname , Antigua and Barbuda , St. Lucia , Dominica , Grenada , St. Vincent , St. Kitts and Nevis , the Grenadines and the Bahamas .

- In Brazil , the term “Latin America” is also used for Spanish-speaking America, similar to the use of the term “Europe” in the United Kingdom.

Concept history

The French economist and pan-latinist Michel Chevalier introduced the term “Latin America” in his 1836 report on his travels through North America Lettres sur l'Amérique du Nord : “The two branches of European civilization, Latin and Germanic, are reproduced in the New World: South America is - like southern Europe - Catholic and Latin, North America belongs to a Protestant and Anglo-Saxon population. ”In this context, there was also talk of a“ Latin race ”.

The term has been used more widely since 1856, when the Chilean politician Francisco Bilbao used it at a conference in Paris. It then quickly spread to Latin America. During the French occupation of Mexico (1862-1867), when Napoléon III. Bringing Archduke Maximilian into play as Emperor of Mexico , French propaganda endeavored to use the term “Latin America” to create the appearance of a congruence between Mexican and French interests - in order to separate and defend against British and US interests. The word replaced the previously common terms Ibero America and Hispano America . The Mexicans drove the French out, but the Latin part remained. A propaganda term coined in Europe, which was directed against the threatening dominance of the English-speaking informal empire in the region, became an albeit anachronistic self-description of the Latin American countries, which was taken up by politicians and writers in order to distance themselves from the former colonial powers and their orientation to express French culture and its current intellectual currents. In view of the cultural stagnation in Spain and Portugal in the 19th century, these became exemplary; when it was received, Latin America was way ahead of its former mother countries. This applies in particular to the positivism of Auguste Comte , which was celebrated as a state cult by some authoritarian regimes in Latin America, particularly in Brazil and Mexico.

The term was adopted relatively quickly in England. The oldest evidence for the occurrence of the term "Latin America" in an official text comes from the year 1863; it can be found in the translation of a speech given by President Gabriel García Moreno to the Ecuadorian parliament: "With the other States of Latin America, excepting the Empire of Brazil, which has a Legation accredited to this Government, we have no continued diplomatic relations."

In Germany, the term caught on much later. Meyer's Konversationslexikon from 1888 does not yet know him, but speaks of "South America".

languages

The predominant language in most of Latin America's countries is Spanish . In Brazil, the most populous country in the region, Portuguese is spoken in its Brazilian variant .

Other European languages that are common in Latin America are English (partly in Argentina, Nicaragua, Panama and Puerto Rico), to a lesser extent also German (in southern Brazil and Chile, in Argentina and in German-speaking places in Venezuela, Uruguay, Paraguay and Alina in Costa Rica), Italian (in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Venezuela) and Welsh (in southern Argentina). In addition, Plautdietsch is still spoken in the widely scattered Mennonite settlements in the Gran Chaco region, among others .

In Peru, Quechua is the second official language alongside Spanish. Kichwa (or Quichua ), which is widespread in the highlands of Ecuador and is related to Quechua, is not an official language there, but is constitutionally recognized. In Bolivia, in addition to Spanish, Aymara , Quechua, Guaraní and 33 other indigenous languages are officially the official language. Guaraní is one of the official languages of Paraguay, along with Spanish, where it is used by a bilingual majority. On the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, English and indigenous languages such as Miskito , Sumo and Rama have official status. Colombia recognizes all indigenous languages spoken in the country as official languages, but less than one percent of them are native speakers. Nahuatl is one of the 62 indigenous languages spoken in Mexico and recognized by the government as a national language alongside Spanish. The best-known indigenous language in Chile is Mapudungun ("Araukanisch") of the Mapuche in southern Chile, Aymara are also common in northern Chile and Rapanui on Easter Island .

religion

Due to its colonial history, Latin America is predominantly Catholic . Around 70% of Latin Americans are Catholic, but the influence of this church is waning, especially in Brazil (only around 60% are Catholics). For several decades the number of members of - partly Pentecostal - Free Churches has been increasing , which today make up around 20% of the population.

population

80% of the population of Latin America lives in the cities, which generate 65% of GDP. 50% of the population is concentrated in 300 cities.

Social movements

Social movements were found in indigenous uprisings against the colonization of Latin America, slave uprisings, the independence movements at the beginning of the 19th century and regional peasant revolts in the 19th and 20th centuries. “In the 20th century, the dynamics of social movements were reflected in a wide variety of phenomena: trade unions and workers' parties, nationalist-populist movements, rural and urban guerrillas and student movements. The indigenous, women's and human rights activities, which have fought for their place in the political public since the 1990s, belong to the so-called New Social Movements ”. The Mexican Revolution with the popular movements around the agrarian revolutionaries Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa , as well as the Cuban Revolution, are considered to be important cornerstones of social movements in the 20th century . A direct result of the Cuban Revolution was the establishment of guerrilla movements in many Latin American countries.

In Chile, attempts were made with the Unidad Popular and Salvador Allende to democratically implement socialism (1970–1973), which was violently ended by the military coup under General Augusto Pinochet . "Pinochet's regime [...] became a prototype of Latin American state terrorism in the 1970s: persecution, torture and the disappearance of thousands ( Desaparecidos )." Finally, the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua (1979–1990) joins the social movements how the women's movement and basic Christian communities played a major role in this sequence of political events.

In the course of the political struggle against the military dictatorships, which ruled almost the entire subcontinent during the 1970s, numerous social movements were formed. In Argentina , for example, the " Abuelas " and " Madres de la Plaza de Mayo ", the grandmothers and mothers of the Plaza de Mayo , organized themselves to clarify the whereabouts of their "disappeared" relatives. A protest movement arose in Chile during the dictatorship, which ultimately won a referendum against General Pinochet. Women's movements also emerged under many dictatorships: "The search for the missing men [...] and the increasingly burdensome care of the family on women led to all kinds of associations: people's kitchens, shopping groups, mutual support networks in official matters, etc."

After the departure of the generals, the social movements in Latin America initially experienced a decline in their activities. At the beginning of the new millennium, a new wave of social movements appeared. As unionization has been weakened, social movements linked to indigenous movements, e.g. B. in Bolivia and Ecuador, an upswing. A characteristic of these movements is their territorial boundaries - in contrast to the orientation towards the factory in earlier social movements. “That means: city quarters are merging, piqueteros, unemployed people block traffic hubs at certain points in the city and raise demands not to shut down the production process from which they fell out, but to shut down the process of circulation.” Nevertheless: “Neither creation nor depends Boosts of mobilization or ways of organizing social movements directly depend on material circumstances. Nevertheless, they are sparked again and again by conflicts about unfulfilled expectations that are definitely based on material foundations. On the one hand, it is still the post-colonial conflict over the land question that is causing social movements to emerge. [...] On the other hand, it is the threatened or enforced withdrawal of social achievements such as free access to education (institutions) that led to the emergence of movements such as the largest student strike at the largest university in Latin America, the UNAM in Mexico City. ”Others Characteristics of the current social movements are the rejection of the avant-garde concept and a demand for society as a whole that goes beyond particular interests and is particularly relevant in processes of democratization. The relationship between movements and parties is ambivalent: while in Mexico and Venezuela, for example, the parties have lost their relevance to the social movements, developments with the MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) in Bolivia and the PT (Workers' Party) in Brazil are turning into the other Direction.

The popular uprising in Argentina in December 2001 made the world see the crisis of representative democracy in Latin America. Within a short time, several presidents were forced to resign and the slogan “¡Que se vayan todos!” (“You [the politicians] should all run away!”) Became generalized. Even before, during and after this general survey, social movements emerged in which some of the aspects described were bundled. In the course of the uprising, various forms of protest were brought together and an association of different strata of the population developed. For example, activists of the unemployment movement (piqueteros) blocked streets, members of the middle class and workers united in neighborhood assemblies (asambleas), workers occupied factories abandoned by their bosses and demonstrated people from the middle class beating cookers in the cities of Argentina (cacerolazo). In particular, parts of the piqueteros went through a politicization surge: "From their original demands for more rights and welfare programs, they went over to criticizing the prevailing economic order as a whole and questioning the political model associated with it."

Research and documentation institutions on Latin America

- CEISAL

- CEPAL

- Cibera

- GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies

- Ibero-American Institute

- Latin America Institute at the Free University of Berlin

- Austrian Latin America Institute

- Latin America Center of the University of Hamburg

- REDIAL

- Central Institute for Latin American Studies of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt (ZILAS)

See also

literature

Monographs

- Renate Pieper : History of Latin America. UTB, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-8252-2830-9 .

- Günther Maihold, Hartmut Sangmeister , Nikolaus Werz (eds.): Latin America. Science and Study Guide . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 3-8487-5247-6

- Stefan Rinke : History of Latin America: From the earliest cultures to the present. Beck-Wissen Beck, Munich 2010 (2nd edition 2014), ISBN 978-3-406-60693-9 .

- Dieter Boris : Latin America's Political Economy: A departure from historical dependencies in the 21st century. VSA, Hamburg 2009.

- Stefan Rinke , Georg Fischer, Frederik Schulze (eds.): History of Latin America from the 19th to the 21st century . Source volume. JB Metzler , Stuttgart, Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-476-02296-7 .

- Bernd Marquardt: State, constitution and democracy in Hispano-America since 1810. Volume 1: The liberal century. 1810 to 1916. (= historical-political studies of the transatlantic area. Volume 1). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotà 2008, ISBN 978-958-701-927-8 . (Excerpts from google books)

- Nikolaus Werz: Latin America. An introduction. 2nd Edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-3586-3 .

- Hans-Joachim König : Small history of Latin America. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-15-010612-5 .

- Romeo Rey: History of Latin America from the 20th Century to the Present. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54093-7 limited preview in the Google book search.

- Walter Mignolo : The Idea of Latin America . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1 .

- Norbert Rehrmann : Latin American History. Culture, politics, economy at a glance. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-55676-6 .

- Walther L. Bernecker (ed.): Handbook of the history of Latin America. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1996 (3 volumes).

- Barbara Tenenbaum (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Vol. 1-5, Scribner & Macmillan, New York 1996, ISBN 0-684-19253-5 .

- Dieter Nohlen , Franz Nuscheler (Ed.): Central America and the Caribbean. 3. Edition. Dietz, Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-8012-0203-8 (Handbook of the Third World, Vol. 3).

- Dieter Nohlen , Franz Nuscheler (Ed.): South America. Dietz, Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-8012-0202-X (Handbook of the Third World, Vol. 2).

- Tulio Halperín Donghi : History of Latin America from Independence to the Present. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-518-40353-2 .

- Renate Hauschild-Thiessen, Elfriede Bachmann : Guide through the sources for the history of Latin America in the Federal Republic of Germany. Bremen (Schuenemann) 1972 ( publications from the State Archives of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, vol. 38).

- Gerhard Schmid: Overview of sources on the history of Latin America in the archives of the German Democratic Republic. Potsdam (Council of Ministers of the German Democratic Republic, Ministry of the Interior, State Archives Administration) 1971.

- Helen Miller Bailey, Abraham P. Nasatir: Latin America. From Iberian colonial empires to autonomous republics. Kindler, Munich 1969.

Collective works

- The Cambridge History of Latin America. 11 volumes from 1984 to 1995. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Trade journals in the German-speaking area

- Atención: Yearbook of the Austrian Latin America Institute

- GIGA Focus Latin America

- Iberoamericana. América Latina - España - Portugal

- ila - Journal of the Latin America Observatory

- Latin America News

- Latin America analyzes

- Ibero-Analyzes: Documents, reports and analyzes from the Ibero-American Institute of Prussian Cultural Heritage

- Matices - magazine on Latin America, Spain and Portugal

- Quetzal: Politics and Culture in Latin America

- Yearbook for the History of Latin America = Anuario de historia de América Latina.

Web links

- Database of indexed literature on the social, political and economic situation in Latin America

- History of Latin America in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Latin America dossier from the Federal Agency for Civic Education

- Cultural and Social Anthropology of Latin America. An introduction

- Latin American Network Information Center

- Working Group on German Latin American Studies

- Quetzal. Politics and Culture in Latin America

- Political science literature on Latin America - the political change in the annotated bibliography of political science

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Peter Gärtner: Latin America - A definition of terms , in: Quetzal: Politics and culture in Latin America. October 2007.

- ↑ Cf. Duden online: Latin America : “Totality of the Spanish and Portuguese speaking countries of Central and South America”. (For the sake of simplicity, Mexico is counted as Central America here.)

- ^ Bertil Malmberg: La America hispanohablante. Madrid 1966, p. 9.

- ^ Walter Mignolo: The Idea of Latin America . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1 , pp. 77-80.

- ↑ Translated here from the 4th edition, 1844 by Verlag Wouters & Cie. published in Brussels, quotation p. 12.

- ^ Walter Mignolo: The Idea of Latin America . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Michael Rössner: Latin American literary history. 2nd ext. Edition. Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, p. 137.

- ↑ Aims McGuiness: Searching for "Latin America". Race and Sovereignty in the Americas in the 1850s. In: Nancy P. Appelbaum et al. (Ed.): Race and Nation in Modern Latin America. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2003, ISBN 978-0-8078-5441-9 , pp. 87-107.

- ↑ Foreign Office : British and foreign state papers , Vol. 53: 1862–1863 . William Ridgway, London 1868, pp. 1068-1074, here p. 1070.

- ↑ Hans Winkler on the Catholic Church and Evangelical-Pentecostal congregations in Latin America , in: Die Presse of March 7, 2016, p. 22f.

- ↑ CAF: ciudades son el motor del desarrollo de América Latina . In: El Comercio , November 2, 2017

- ↑ a b Federal Agency for Civic Education

- ^ Dieter Boris: Social movements in Latin America. Hamburg 1998.

- ↑ Dieter Boris: Neoliberalism and the popular movements - where is the development in Latin America going?

- ^ A b Jens Petz Kastner: Modified Strength - Social Movements in Latin America at a Glance

- ↑ Timo Berger: When the unemployed get mobile, nothing goes anymore - road blockades, marches and neighborhood help

- ↑ ZILAS ( Memento from June 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive )