Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels (born November 28, 1820 in Barmen (now part of Wuppertal ) in the Prussian province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , † August 5, 1895 in London ) was a German philosopher , social theorist , historian , journalist and communist revolutionary . He was also a successful entrepreneur in the textile industry . Together with Karl Marx he developed what is now called Marxismdesignated social and economic theory .

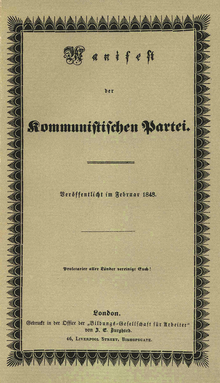

Even before Marx, Engels dealt with the critique of political economy . The Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy , published in 1844, became the starting point for Marx's own work. As early as 1845, the joint work The Holy Family appeared , with which Engels and Marx began to formulate their theoretical understanding. In 1848 they wrote the Communist Manifesto on behalf of the League of Communists .

With his influential study The Situation of the Working Class in England (1845) Engels was one of the pioneers of empirical sociology. His journalistic activity contributed significantly to the spread of Marxism. In addition to the Anti-Dühring (1877), the short version The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science (1880) was particularly well received . After Marx's death in 1883, Engels published the second and third volumes of his main work, Das Kapital . Critique of Political Economy , out. In addition, he continued the work on the theoretical development of their common worldview , including in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884) and Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of classical German philosophy (1888).

In addition to his economic and philosophical studies, Engels also dealt intensively with the development of the natural sciences and mathematics, thus laying the foundation for the later dialectical materialism .

He clearly foresaw the danger of a world war in Europe and tried in 1893 with a series of articles in Vorwärts to give an impetus to reduce the standing armies .

life and work

Childhood and Adolescence (1820–1841)

Engels was the first of nine children of the successful cotton manufacturer Friedrich Engels (1796-1860) and his wife Elisabeth Franziska Mauritia Engels (née van Haar). Engels' father came from a respected, since the 16th century in Bergisch Land -based family and became the pietism close. His mother came from a family of philologists. In his native town of Barmen (today in Wuppertal ) he attended the municipal school. In the autumn of 1834 his father sent him to the liberal high school in Elberfeld . The extremely linguistically gifted student was enthusiastic about humanistic ideas and came into increasing opposition to his father. At his insistence, Engels had to leave grammar school on September 25, 1837, a year before his Abitur , to work as a clerk in his father's business in Barmen. In July 1838 he traveled to Bremen to continue his training there until April 1841 in the house of the wholesaler and Saxon consul Heinrich Leupold . He lived in the household of Georg Gottfried Treviranus , pastor at the Martini Church .

In cosmopolitan Bremen, in addition to his commercial training, Engels had the opportunity to pursue the liberal ideas spread through the press and book trade . He felt addressed above all by the liberal poets and publicists of " Young Germany " and made literary attempts himself.

In the spring of 1839, Engels began to deal with the radical pietism of his hometown. In his article Letters from Wuppertal , which appeared in the Telegraph for Germany in 1839 , he described how religious mysticism permeated all areas of life in Wuppertal and drew attention to the connection between the pietistic attitude to life and social misery. In 1840 he reported on the church dispute in Bremen .

Engels worked as the Bremen correspondent of the Stuttgarter Morgenblatt for educated readers , from 1840 on with the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung . He wrote numerous literary reviews, poems, dramas and various prose works. In addition, he wrote reports on the question of emigration and on the "screw steamship". Important supporters of his literary and political interests at this time were Ludwig Börne , Ferdinand Freiligrath and especially Karl Gutzkow . In his Telegraph für Deutschland , from 1839 to 1841, numerous contributions by Engels appeared under the pseudonym "Friedrich Oswald".

From September 1841, Engels did his military service as a one-year volunteer with the Guard Artillery Brigade in Berlin , where he attended lectures on philosophy at the university . He approached the group of Young Hegelians and joined the group around Bruno and Edgar Bauer , the so-called “free”. At the turn of the year 1841/42, Engels published - under the impression of Schelling's Berlin Hegel lectures - an article and two brochures directed against Schelling's philosophy.

Since his pamphlets against Schelling, Engels has paid increasing attention to philosophy. He studied the works of Hegel, dealt extensively with the state of research critical of religion and turned for the first time to the philosophy of the French materialists . From mid-1842 he began to deal with Ludwig Feuerbach ( Das Wesen des Christianentums ), who rejected religion and Hegelian idealism in his works. Under the impression of these studies, Engels increasingly distanced himself from Young Hegelianism and began to take positions of materialism. As a result, political questions of the day became more and more important to him. From April 1842 he published articles directed against the reactionary course of the Prussian state in the Rheinische Zeitung , the leading organ of the opposition bourgeois movement in Germany at the time.

Letters from the Wuppertal and occupation with the Young Hegelians

Engels became interested in the precarious situation of the workforce very early on. In the essay Letters from Wuppertal , published in the Telegraph für Deutschland as early as 1839 , he describes, among other things, the degeneracy of German industrial workers - such as the spread of mysticism and drunkenness - and child labor in the factories.

In addition, Engels dealt closely with the Young Hegelians in the period that followed, in particular with David Friedrich Strauss . In the years 1842/43 - under the influence of Schelling's Hegel lectures in Berlin - articles and brochures on Schelling and his criticism of Hegel appeared. Engels criticizes Schelling's attempt to justify the Christian religion and defends the Hegelian dialectic. Schelling's philosophy represents a relapse into scholasticism and mysticism and is the attempt to humiliate philosophy again to the "handmaid of theology".

First revolutionary steps (1842–1844)

In November 1842 Engels traveled via Cologne - where he first met Karl Marx in person while visiting the editorial office of the Rheinische Zeitung - to Manchester , where he lived in the Chorlton-on-Medlock district, to complete his commercial training in the cotton spinning mill owned by his father and his partner Ermen Ermen & Engels to complete.

In England, which was much more industrially developed, Engels got to know the reality of the working class there, which changed his political stance and shaped it for life. The feudalism was already overcome there, and the contradictions between the bourgeoisie and the working class were open to Engels revealed. He sought contact with the British labor movement that was forming and got to know their forms of struggle, such as strikes , meetings and legislative initiatives . The Irish worker Mary Burns , Engels' partner, played an important role.

In 1843 Engels made contact with the first revolutionary German workers' organization, the “ League of the Just ”, in London , and met leading members such as Heinrich Bauer , Joseph Moll and Karl Schapper . At the same time he made contact with the English Chartists in Leeds and wrote the first articles that appeared in the newspapers of the Owenists (The New Moral World) and Chartists (The Northern Star) . In the autumn of 1843 his friendship with the Chartist leader Julian Harney and the commercial assistant and poet Georg Weerth , who was later to head the feature section of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in the revolutionary years 1848/49, goes back to.

Moved by the tough struggles of the English proletariat, Engels immersed himself in the study of the existing theories of capitalist society. He resorted to the works of the English and French utopians ( Robert Owen , Charles Fourier , Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon ) and the classic bourgeois political economy ( Adam Smith , David Ricardo ). He published the results of his studies in the Rheinische Zeitung , in English worksheets and in a Swiss magazine. In February 1844, the writings Die Lage Englands und Umrisse were published on a critique of political economy in the Franco-German yearbooks published by Karl Marx and Arnold Ruge in Paris . In it he tried to give an initial answer to the question of what role economic conditions and interests play in the development of human society.

Shortly after his arrival in Manchester, Engels met the Irish workers Mary and Lizzie Burns , with whom he had been in love throughout his life. One day before Lizzie's death (September 11, 1878) he officially married her.

Engels has been in regular correspondence with Marx since his collaboration on the Franco-German yearbooks . When he returned to Germany at the end of August 1844, he visited him in Paris for ten days. The two found their views concurred and decided to continue to work closely together.

Outlines for a Critique of Political Economy

With his arrival in England (1842), the confrontation with Chartism and the first historical debates of the labor movement, Engels' interest shifted to the analysis of the social and political situation of the working class. He came to the conviction that the struggle of material interests is the main drive of social development, which finds its political expression in the class struggle. His theoretical views at the time are best expressed in Outlines on a Critique of Economics. In it, Engels formulates his critique of idealistic and materialistic philosophy. He highlights private property as the central category of capitalism , which is the reason for the alienation of work, for the formation of monopolies and for the recurring crises. Engels sees the solution to the problems of capitalism in a rational organization of production.

First collaboration with Karl Marx (1844–1847)

After his return to Barmen, Engels found changed circumstances. The uprising of the Silesian weavers in June 1844 had triggered workers' strikes in other parts of Germany as well. This also influenced the bourgeois forces in Rhenish Prussia to oppose the Prussian government. In order to support the opposition forces, Engels tried to establish contact with the socialists working in the Rhineland , whose leading theoretician was Moses Hess . With him and the painter and poet Gustav Adolf Koettgen , he developed a lively agitational activity in Elberfeld from autumn 1844 . In the Elberfeld speeches of February 1845, Engels propagated a communist society, whereupon the provincial government banned all public meetings. He now concentrated on strengthening the links between the illegally working socialist groups and cultivated his international relations - especially with the English socialists and Chartists. For the socialist magazine The New Moral World , on which he had already worked in England, he wrote several articles in which he reported on the development of socialist currents in Germany. In addition, he tried to win the various groups for the ideas represented by Marx and him and to overcome the prevailing idealistic and utopian-socialist ideas. An important event was the appearance of the Holy Family , a joint effort with Marx, in February 1845. The scientific public in Germany reacted with mostly violent attacks on the materialistic-socialist ideas contained therein. In order to advance the theory of the class struggle, Engels worked intensively since his arrival in Barmen on his work The Situation of the Working Class in England , which was published in March 1845 by Otto Wigand . It was discussed in the most important German newspapers and magazines and met with great interest from the democratic forces of the middle class.

In April 1845, Engels moved to Brussels to support Marx, who, under pressure from the Prussian reaction, had been expelled from France by the French government and moved to the young Kingdom of Belgium. In the same year he was followed by Mary Burns from England. Marx and Engels built up a mutual circle of friends and acquaintances in Brussels, which included Moses Hess, Ferdinand Freiligrath , Joseph Weydemeyer and Joachim Lelewel , among others . Marx and Engels found that ideas spread throughout the communist movement that hampered the absorption of their new knowledge. They therefore began to work on the text Die deutsche Ideologie , which included a criticism of Feuerbach and the "since then German socialism". They finished their work in May 1846 after six months. Engels tried in vain to find a publisher until 1847 and at the beginning of 1847 wrote the work The True Socialists as a supplement . After they had laid the theoretical foundations for the future transformation of society from their point of view, Marx and Engels saw their most important task in winning “the European and first of all the German proletariat” to their convictions. After 1846 they devoted themselves more and more to practical work for the formation of a proletarian party. In February 1846, together with Philippe Gigot , they founded the Communist Correspondence Committee in Brussels , which was supposed to establish links between the communists in the various countries. In the course of 1846 further committees were founded in numerous European cities. Marx and Engels considered these mostly small groups to be the basis on which to introduce their ideas into the workers' movement and to deal with those ideological concepts which until then had determined the world of ideas of the workers. This included above all Wilhelm Weitling's utopian communism , the teachings of the French socialist Proudhon and the conception of “true” socialism ( Karl Grün ).

At the end of January 1847, Marx and Engels joined the “League of the Just”, which had meanwhile come closer to their ideas. They were now working vigorously to transform the "Bund" into a party of the working class. Meanwhile, in Brussels, Marx was writing his theoretical pamphlet Misère de la philosophie (The misery of philosophy) , which came out in France in July 1847 and contained a criticism of Proudhon's reform plans. In Paris, Engels propagated the theoretical questions dealt with in the book among the German communists and the leaders of the French socialists. In June 1847 the first of the two federal congresses of the “League of the Righteous” took place, which was now renamed the “ League of Communists ” because its members were no longer concerned with “justice”, but rather the attack on “the existing social order and the Private property ”was in the foreground. In place of the old federal motto “All people are brothers” there was now the revolutionary class slogan “Workers of all countries, unite!”. In the form of 22 questions and answers, the congress decided on the “ Draft of a Communist Creed ”.

In August 1847 Engels founded the Brussels German Workers' Association together with Marx , and in September the Association démocratique - based on the model of the London Fraternel Democrats . At the beginning of November 1847, Engels - commissioned by the Parisian members of the “League of Communists” - wrote the principles of communism . In the same month Marx and Engels attended the second congress of the "League of Communists" in London, where they were instructed to further develop the program of the union, which resulted in The Communist Manifesto , which appeared in London in February 1848. In the background of their work stood the expectation that the bourgeois revolution of 1848 would result in the proletarian overthrow of the existing social conditions in Germany. Engels also became active in dealing with 'true socialism' in the Deutsche-Brusser-Zeitung .

The situation of the working class in England

After his return from England to Germany, Engels wrote The Situation of the Working Class in England from November 1844 to March 1845 . The work, published in 1845, is Engels 'first major independent publication. It fell at a time of particular social tensions in Germany ( weavers' revolt ). Engels turns here to the social question - starting from the conditions in England, which he knew from his own experience. He describes the miserable living quarters of the workers in the English industrial cities and describes the work situation of the proletariat, points out child labor, occupational diseases and mortality rates. Finally he informs about the additional gagging of the working class families by the compulsion to buy groceries from the entrepreneurs and to live in the apartments provided by them ( truck and cottage system ).

Joint processing

The friendship that he had with Marx in September 1844 initially led to a joint work-up of their philosophical point of view. Their first joint work The Holy Family or Critique of Critical Criticism (1845) marks their transition from idealism to materialism. In it, Marx and Engels settle accounts with their former Young Hegelian comrades, especially Bruno Bauer . They accuse Bauer's "critical criticism" of not focusing on people but on "categories" - spirit and self-confidence - and falling behind the level reached by Feuerbach, which long ago overcome the speculative idealism of Hegel's philosophy.

In response to the polemical contributions of Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner in Wiegand's quarterly journal , the probably most important manuscripts of this period, Die deutsche Ideologie , were written by May 1847 . Critique of the newest German philosophy in its representatives, Feuerbach, B. Bauer u. Stirner, u. of German socialism in its various prophets . In it, Marx and Engels (as well as Joseph Weydemayer , Moses Hess and Roland Daniels ) summarize their criticism of the Young Hegelian philosophy, whose demand for a change in consciousness amounts to only interpreting what exists differently, but otherwise recognizing it. Feuerbach's materialism, Bauer's philosophy of self-confidence and Stirner's individualistic anarchism left the practical conditions unchanged despite all the theoretical radicalism. In addition, they criticize German socialism , which is cosmopolitan but shows “national narrow-mindedness”. It had degenerated from a social movement to a purely literary movement and so only satisfied the needs of the German petty bourgeoisie.

With the separation from the Young Hegelians and Socialists, the positions of Marx and Engels became radicalized. In 1847 they were commissioned by the Second Congress of the League of Communists to draft the Communist Party's manifesto . The work formulates the class struggle as a principle of previous history and understands the rise of the modern bourgeoisie as the victory of a revolutionary class. With its victory, however, the bourgeoisie would lose its revolutionary role and inhibit the further development of the productive forces . In its struggle against feudalism, the bourgeoisie had destroyed all traditional relationships between people and replaced them with “pure money”. The condition of the capitalist society it has created is wage labor, its consequence the proletariat , which through its labor increases capital without being able to procure property for itself. The bourgeoisie thus produce "above all their own gravedigger". The manifesto closes with the call to struggle “Workers of all countries, unite!” Although it did not achieve any direct political effectiveness, it later became the basis of socialist and communist party programs.

From the March Revolution to moving to London (1848–1870)

After the outbreak of the March Revolution in Vienna and the barricade fighting in Berlin (March 1848), Marx and Engels met in Paris and worked out the demands of the Communist Party in Germany , which were printed out as a leaflet. Then both left Paris and arrived in Cologne in April to begin preparations for the foundation of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung ; under the conditions of the freedom of the press that had just been won , a large daily newspaper appeared to be the most effective means of representing political goals in public. Marx became editor-in-chief of the new newspaper, Engels his deputy. Because of imminent arrest, Engels had to leave Cologne in September 1848 and went to Switzerland to help organize the workers' associations. In January 1849 he returned to Cologne, where he was acquitted by the Cologne jury in the press trial against the Neue Rheinische Zeitung .

In May 1849 Engels actively supported the Elberfeld uprising at times . A month later he joined the Baden-Palatinate army and took part as Willich's adjutant in the revolutionary battles against Prussia in Baden in the battle in Gernsbach and the Palatinate . Here he first met Johann Philipp Becker , the commander of the Baden People's Army, with whom he later became a close friend. His criticism of the half-hearted politics of the Baden revolutionary government and the ultimately unfortunate campaign he later put down in his work The German Reich Constitution Campaign . After the defeat of the March Revolution , Engels, like many revolutionary emigrants, fled to England via Switzerland.

In September 1850 the Communist League split. Two months later, Engels worked again at Ermen & Engels in Manchester and later took over his father's share, which he finally sold to Ermen (1870). Engels began to study military affairs; Due to his practical military experience in military service and the fighting in Baden, he developed into a military expert, which earned him the nickname "General". At the end of 1850 he also began to learn Russian and other Slavic languages and studied the history and literature of the Slavic peoples. He continued his language studies in 1853 by learning Persian. Engels spoke twelve languages actively and twenty passively, including Ancient Greek , Old Norse , Arabic , Bulgarian , Danish , English , French , Frisian , Gothic , Irish , Italian , Latin , Dutch , Norwegian , Persian , Portuguese , Romanian , Russian , Scottish , Swedish , Serbo-Croatian , Spanish , Czech .

The year 1850 also saw the beginning of the constant correspondence with Marx. Under the name of his friend he wrote regularly from 1851 to 1862 for the New York Daily Tribune magazine . From 1853 to 1856 he published various articles on the Crimean War and other international events in the New York Daily Tribune and in the Neue Oder-Zeitung .

From 1857 to 1860 Engels worked on the New American Cyclopaedia published by Charles Anderson Dana in New York and produced a number of military articles as well as biographical and geographic articles. He also wrote numerous newspaper articles, including on the war in Italy of 1859 for the workers' newspaper Das Volk .

At the end of the 1850s and the beginning of the 1860s, Engels dealt with emerging European nationalism in two writings . In April 1859 the work Po und Rhein appeared in Berlin as an anonymous brochure , in which he turned against Austrian supremacy in Italy and was convinced that only an independent Italy would be in Germany's interests. For the Germans he called for the "unity that [...] alone can make us strong internally and externally". At the beginning of 1860 he published the writing Savoyen, Nizza und der Rhein anonymously , in which he opposed the annexation of Savoy and Nice by Napoleon III. and warned of a "Russian-French alliance".

While Engels was shaken by a number of private incidents in the early 1860s - the death of his father (1860), that of his wife Mary Burns (1863), and his longtime comrade Wilhelm Wolff (1864) - two political events drew attention Engels and Marx on themselves. The American Civil War (1861–1865) both regarded as a "drama without parallel in the annals of war history". Engels called on the northern states to wage the war in a revolutionary way and to involve the popular masses more. He stressed that the struggle for the liberation of blacks was the very own cause of the working class and that even white workers could not be free as long as slavery existed. In the Polish uprising against tsarist Russia (1863), Engels saw an important prerequisite for weakening the reactionary influence of tsarism in Europe and for developing the democratic movement in Prussia, Austria and Russia itself.

After Ferdinand Lassalle's death (September 1864), Engels worked on the ADAV's newspaper , Social-Demokrat , at Marx's suggestion , in order to win over its members for revolutionary politics. In February 1865 they both stopped working as the paper was increasingly seeking Bismarck's closeness. In 1865 the brochure The Prussian Military Question and the German Workers 'Party appeared in Hamburg , in which Engels was primarily concerned with recalling a revolutionary position against the Lassalleans and the General German Workers' Association.

After Marx had worked on the creation of capital since the 1850s , the first volume appeared in September 1867. Engels had made Marx's long-term economic studies possible in the first place by undertaking “dog-like commerce” and the livelihood of the Marx family denied to a large extent. Engels was able to advise Marx on all areas of economic theory. His advice on practical matters was also of great value. Since no workers' newspapers were initially available for the dissemination of the ideas contained in Capital , Engels published several reviews of Marx's work in the bourgeois press under the guise of criticism. In 1868 he was able to honor the work as the most important book for the working class in Wilhelm Liebknecht's new Democratic Weekly Journal without the previous restrictions.

In London until the death of Marx (1870-1883)

In October 1870, Engels and Lizzie Burns moved to London near Marx's apartment. Meanwhile, the Franco-German War had broken out in Central Europe . Marx and Engels found it difficult "to reconcile themselves with the idea that instead of fighting for the destruction of the empire, the French people sacrifice themselves for its enlargement". They believed that the French war was a dynastic war designed to secure Bonaparte's personal power. The German workers would therefore have to support the war as long as it remained a defensive war against Napoleon III, the main enemy of the national unification of Germany. From late July 1870 to February 1871, Engels anonymously wrote 59 articles about the course of the war for the London daily Pall Mall Gazette , which caused a sensation in London because of their military expertise. Had Engels until the defeat of Napoleon III. (September 2, 1870) still held the view in his articles that Germany was defending itself against French chauvinism, afterwards the war for him "slowly but surely turned into a war for the interests of a new German chauvinism".

In October 1870, Engels was elected a member of the General Council of the International Workers' Association at the suggestion of Marx . In the following years he worked as the corresponding secretary for Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Italy and Denmark. After the defeat of the Communards of the Paris Commune , the General Council formed a refugee committee for the Paris refugees, who mostly flocked to London. At Engels' initiative, Marx wrote The Civil War in France , which was intended to emphasize the importance of the Paris struggle for all members of the “International”; Engels translated this script from English into German in mid-1871.

Since 1873 Engels dealt intensively with philosophical problems in the natural sciences. His intention was to write a book after thorough preparatory work in which he wanted to give a dialectical-materialistic generalization of the theoretical knowledge of the natural sciences. In the midst of these studies, Liebknecht and Marx asked him to counteract the “Dühringsseuche” in Germany. He fulfilled this task from 1876 to 1878 with the writing of Mr. Eugen Dühring's revolution in science (Anti-Dühring) . It first appeared in book form in Vorwärts , the central organ of the Socialist Workers' Party in Germany , in 1878. In 1878 his wife Lydia Burns died .

Dialectics of Nature and Anti-Dühring

After retiring from the company (1869), Engels' publications aimed at the “conceptual clarification, historical deepening and methodological delimitation of scientific socialism”. The dialectic of nature fragment was created from 1873 to 1882 . Engels was motivated to the work by the criticism of the emerging natural sciences of the philosophy of Hegel and the transfer of scientific theories to society. Engels wants to prove that the same laws of motion can be discovered in nature that also apply in history. In addition to the theses of the eternity of matter and movement, he formulates the three basic laws of dialectics . Engels contrasts dialectics with “metaphysical” thinking, which is based on rigid categories instead of contradicting processes. With the help of many examples, Engels wants to show that nature is not structured “metaphysically” but rather dialectically. With great attention to detail, he processes almost all scientific insights and discoveries of his time.

In the work of Mr. Eugen Dühring's revolution in science ("Anti-Dühring"), published in 1877/78 as a series of articles in Vorwärts with the collaboration of Karl Marx, Engels critically examines some of the works of Eugen Dühring . His criticism is directed against the dogmatic-metaphysical character of Dühring's "philosophy of reality" and its inability to understand the "dialectical" development process of the world. At the same time, the work is a first attempt at an encyclopedic summary of both the history of socialism and the doctrines of Marxian communism.

The essay, based on the Anti-Dühring and first published in 1880, the development of socialism from utopia to science develops the principles of historical materialism . For Engels, early socialism ( Saint-Simon , Fourier , Owen ) was " utopian " because it appealed undialectically to timeless rational truths. Hegel remedied this deficiency by viewing the whole of reality as a dialectical process of development - albeit in the wrong way as the unfolding of the “idea”. It was only Marx who, through his conception of history as the history of class struggles and the discovery of “ surplus value ” as the “secret of capitalist production”, made socialism a science. He proved that bourgeois society must necessarily fail because of the logic of its fundamental contradiction between social production and private appropriation. While it was the historical task of the bourgeoisie to develop the productive forces, it is now the task of the proletariat to enforce their social appropriation.

After Marx's death (1883–1895)

After the death of Marx (1883) Engels became the main adviser to the “Marxist” influenced part of the international, especially the German, labor movement. He influenced the development of German social democracy and its Erfurt program (1891).

He also took on the editing and editing of Marx's works as well as the supervision of new translations. Under the conditions of the Socialist Law in Germany (1878–1890), Engels brought out a new edition of the first volume of the capital in 1883 . In preparing it, he took into account some of the most important changes from the French edition.

In 1884 he published the work The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State , based among other things on Marx's manuscripts , in which he adopted an evolutionist five-stage model of social formations from primitive society through slave-holding society , feudalism and capitalism to communism.

Then Engels began to organize and decipher Marx's manuscripts. In 1885 he published Marx's The Misery of Philosophy and the second volume of Capital . This was followed by the English translation of the first volume (1887), which he prepared together with his friend Samuel Moore and Marx's son-in-law Edward Aveling . In 1890 the fourth version of the first volume of the capital appeared , edited again by Engels , in which he added a few footnotes that were supposed to take account of the changed "historical circumstances". The edition of the third volume, which took Engels nine years to produce (1895), turned out to be very difficult. He took Marx's manuscript from 1864/65 as the basis, which he edited extensively.

In addition to the edition of the capital, Engels published Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of classical German philosophy in 1886, and in 1891 Marx's critique of the Gotha program , written by Marx in 1875 . In addition, he conducted lively correspondence with socialists and communists throughout Europe.

Engels died of throat cancer on August 5, 1895 in London at the age of 74. Since his preference for the seaside resort of Eastbourne was known, the urn with his ashes was sunk into the sea on September 27, 1895, five nautical miles off the coast there at Beachy Head . In his will, Engels left a cash fortune of around £ 30,000 (about 600,000 gold marks).

Late work

After the death of Marx (1883), Engels' main aim was to disseminate, defend and continue the scientific and political work he had created together with Marx. Instead, he put his own work on hold, such as that on the dialectic of nature .

Engels' primary concern was initially to work on capital and to publish the manuscripts left by Marx. In his own writings, he tried to convey the revolutionary traditions to the developing labor movement. Accordingly, the processing of the history of the early socialist movement and the revolution of 1848/49 took a large part. Works such as Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung , On the History of the League of Communists and the preface to Karl Marx before the Cologne jury emerged . As a means of representation, Engels repeatedly chose the biography - for example about the workers' leaders Georg Weerth , Johann Philipp Becker and Sigismund Ludwig Borkheim .

Engel's historical interest also related to the subject of " prehistory ". In The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State , he analyzed the social formation of primitive society and the transition to class society.

In addition, he dealt extensively with German history. As part of his planned revision of the German Peasants 'War , he dealt with the history of the German Peasants' War , which he saw as the "pivot of all German history". The emergence of the German nation-state and the politics of Bismarck were the subject of the manuscript The Role of Violence in History , written at the end of 1887 to April 1888 , which remained unfinished. Since the beginning of 1885 a series of essays on the history of the English labor movement ( England in 1845 and in 1885 ) have been written around the American edition of the situation of the working class in England .

Engels also worked on the history of Russia and France. In 1889/90 the foreign policy of Russian tsarism appeared , and in 1891 the French translation of Karl Marx's Eighteenth Brumaire appeared in the features section of the Socialiste . This was followed by the new edition of Karl Marx's Civil War in France , to which Engels wrote an introduction.

The history of early Christianity interested him because of its "strange points of contact with the modern labor movement". Like this, early Christianity was “originally a movement of the oppressed: it first appeared as a religion of slaves and freed, of the poor and without rights [...]. Both are persecuted and harassed, their followers ostracized and placed under exceptional laws ”. His approach was in line with the historical-critical biblical research of his time. In the essay The Book of Revelation , published in 1883, Engels examined the Revelation of John , which he regarded as the most important New Testament source for research into the history of early Christianity. In the summer of 1894 he dealt with the topic of “primitive Christianity” again in detail in the work on the history of primitive Christianity , which was published in the Neue Zeit , and included thoughts from the 1883 essay.

Another important topic for the late Engels was the repeated examination of the philosophical sources of Marxism. In 1886, in the work Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of classical German philosophy, he set out the relationship between Marxism and the philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach. Engels understood this text itself as "the most detailed exposition of historical materialism" that he knew existed.

Theoretical basic concepts

Although Engels put most of his theoretical and practical work in the service of Marx, he opened up areas of Marxist theory to which Marx paid little attention. In particular in the classical disciplines of philosophy such as epistemology , ontology and anthropology and the theory of history , Engels is considered an independent thinker.

philosophy

starting point

In contrast to Marx, Engels only developed his philosophical views later, when he was intensively concerned with the natural sciences - especially with regard to the problem of dialectics. At this point Engels was faced with the task of defending the dialectic against Dühring's attacks and at the same time setting out the principles of a new philosophy that differed from both the previous idealism and from the vulgar materialism that dominated at this time. In all the fundamental discussions, Hegel was the defining figure on which he based his considerations.

dialectics

Engels understands dialectics not only as a historical, but above all as an ontological and epistemological principle. It is the way of movement and development of all beings and at the same time the method of thinking. Engels developed three dialectical laws :

- "The law of the permeation of opposites"

- "The law of turning quantity into quality and vice versa"

- "The law of the negation of negation"

For Engels, matter is essentially in motion. Movement is contradictory, which already results from the fact that a moving body is “in one and the same moment of time in one place and at the same time in another place, in one and the same place and not in it”. On the basis of Engels' assumption that everything real is material and everything material is essentially moved, it can then be said that everything real contains contradictions or that opposites necessarily permeate each other.

The law of converting quantity into quality says "that in nature [...] qualitative changes can only take place through quantitative addition or quantitative withdrawal of matter or movement".

According to Engels, the law of negation of negation is a general “law of development of nature, history and thought”, which he only presents using examples. So the plant that arises from a grain of barley, its negation, the numerous grains that the plant produces, is the result of the negation of the negation.

Engels contrasts the dialectical with the metaphysical mode of thinking . This works with "fixed" categories, while the dialectical one - among whose representatives he counts Aristotle and above all Hegel - with "fluid" categories. In Engels' view, the “fixed opposites of reason and consequence, cause and effect, identity and difference, appearance and essence” of the metaphysical way of thinking are untenable, since the one pole in the other is already “in nuce” and “in a particular one Point that turns one pole into the other ”. The metaphysical way of thinking is the "ordinary" one, which both everyday thinking and science need in order to orientate itself in the world, and it "had great historical justification at its time". It is a necessary level of everyday and scientific knowledge that cannot simply be skipped over in favor of dialectic, but is suspended in it as a moment .

Knowledge and logic

In the Anti-Dühring , Engels developed his image theory in principles . For him, consciousness and thinking are the “products of the human brain”; man is "a natural product himself". The "logical schemes" refer to "forms of thought" which in turn are "forms of being, of the outside world". Like Hegel, Engels denies the " thing in itself " thesis ; for this does not add "a word to our scientific knowledge, because if we cannot deal with things, they do not exist for us". Knowledge is a “historical product which at different times assumes very different forms and thus very different contents. The science of thinking is, like any other, a historical science, the science of the historical development of human thought ”.

Engels joins Hegel's criticism of the formal-logical principle of identity . Science has shown that identity also includes diversity. Likewise in Hegel's sense, Engels interprets the judgment as the unity of the general and the particular.

Ideology, morality and religion

For Engels, ideology is “a process that is carried out with awareness by the so-called thinker, but with a false awareness. The actual driving forces that move him remain unknown to him ”. To the ideologist, his ideas appear “because they are mediated through thinking, also ultimately based on thinking”. These driving forces include both obscure subjective interests and the objective economic constellation. On the other hand, Engels also emphasizes the “historical effectiveness” of the ideology. Their “denying independent historical development” does not mean that they “once brought into the world by other, ultimately economic causes, now also reacts” and that they cannot react on their surroundings, even their own cause.

The development of an ideology follows a certain intrinsic logic, it develops "in connection with the given subject matter". So "the philosophy of every epoch has a certain material as a prerequisite, which was handed down to it by its predecessors and from what it is based". Nevertheless, the economic influences largely determine “the type of modification and further development of the material of thought”. They usually do not have a direct effect, but mediate, since "it is the political, legal, moral reflexes that have the greatest effect on philosophy".

Typical examples of ideologies for Engel are morality and religion. The morale was "always a class morality; it either justified the rule and the interests of the ruling class, or, as soon as the oppressed class became powerful enough, it represented indignation against this rule and the future interests of the oppressed ”. The origin of the ideological form of religion is man's powerlessness in relation to nature. The low level of mastery of nature and the dependence on unknown natural events caused religious-magical practices to compensate for the economic-technical and scientific underdevelopment: “These various misconceptions about nature, about the nature of man himself, about spirits, magic powers etc. negative economic underlying; The low economic development of the prehistoric period complements, but in some places also is a condition and itself a cause, the wrong conceptions of nature ”.

history

Engels shared with Marx the basic assumption that the history of mankind is a “history of class struggles” and that its course is essentially determined by economic conditions. In Anti-Dühring and in his later writings, Engels worked out the historical-philosophical conceptions.

Engel's view of history is characterized by a fundamental optimism. Like Hegel, he does not understand human history as a "desolate tangle of senseless violence", but as a development process whose inner regularity can be perceived through all apparent coincidences.

For him, history is primarily the work of people - “we make our own history” - but “the really active motivations of the historically acting people are by no means the ultimate causes of historical events”. Rather, “behind these motives there are other moving forces [...] that need to be researched”. For Engels, the connection between the freedom of the individual and the regularity of the historical process can only be understood dialectically. The "purposes of the actions" are willed, but not "the results that really follow from the actions". The historical events appear "as governed by chance", but are "governed by internal hidden laws". In order for these to be effective, however, a certain degree of maturity in historical development must first have been reached: “History has its own course, and however dialectical this may ultimately be, the dialectic must often focus long enough on history waiting".

The decisive condition for the historical development are the economic conditions - the way in which people produce their livelihood and exchange their products. They and the social structure resulting from them form the basis “for the political and intellectual history” of every historical epoch.

The economic factors

In his late work in particular, Engels developed a comprehensive concept of the determining "economic factors". In his letter to Borgius, he includes “the entire technology of production and transport”, geography, “ tradition ” and also “ race ”. They form the basis of the historical course, but are not the only determining factor. The “various moments of the superstructure - political forms of the class struggle and its results - constitutions, determined by the victorious class after a battle has been won, etc. - legal forms, and now even the reflexes of all these real struggles in the brains of those involved, political, legal, philosophical theories , religious views and their further development into dogma systems, also exert their influence on the course of historical struggles and in many cases mainly determined their form ”.

For Engels, the economic laws are not eternal natural laws of history, but historical laws that arise and pass. Insofar as they express “purely bourgeois relationships”, they are no older than modern bourgeois society. They only remain valid as long as this society based on class rule and class exploitation remains alive. In this context, Engels also takes a position on Malthus's population law . It is only a law for civil society and proves that it has become a barrier to development and must therefore fall.

Primordial communism and civilization

An essential element of Engels' late work was the examination of prehistory, the importance of which only became clear to him when he read the works of Haxthausen , Maurer and Morgan .

For Engels, all history is based on the original community of land owned by the tribal and village communities. He raves about the gentile society and its "wonderful constitution in all its childlike and simplicity". Similar to Rousseau , he contrasts the present with two golden ages - at the beginning and at the end of history.

Engels vividly describes the age preceding all division of labor and the founding of states in romantic language:

“Without soldiers, gendarmes and policemen, without nobility, kings, governors, prefects or judges, without prisons, without trials, everything goes smoothly. All quarrels and quarrels are decided by all those concerned, the gens or the tribe, or the individual gentes among themselves - blood revenge , of which our death penalty is also only the civilized form, threatens as an extreme, rarely used means all the advantages and disadvantages of civilization. Although there are far more common matters than there are now - the housekeeping is common and communist to a number of families, the land is tribal, only the gardens are provisionally assigned to the housekeeping - one does not need a trace of our extensive and complex administrative apparatus. It's up to the parties involved, and in most cases centuries of use have settled everything. There can be no poor or needy - the communist household and the gens know their obligations towards the old, the sick and paralyzed during the war. All are equal and free - women too. There is still no room for slaves, nor generally for subjugation of foreign tribes. "

The original gentile communities were doomed because they did not go beyond the tribe; “What was outside the tribe was outside the law”. They could only exist as long as production remained completely undeveloped. Despite this insight, Engels criticizes the civilizational development that followed:

“It is the lowest interests - common greed, brutal lust for pleasure, filthy greed, selfish robbery of common property - that inaugurate the new, civilized, class society; it is the most shameful means - theft, rape, deceit, treason, that undermine and overthrow the old classless gentile society. And the new society itself, during the entire three-and-a-half thousand years of its existence, has never been anything other than the development of the small minority at the expense of the exploited and oppressed great majority, and it is so now more than ever before. "

Country

For Engels, the state is a historical product. Engels explains this using the example of the emergence of the Athenian state. This developed out of the originally communist gentile society . With the inheritance of wealth to the children, the accumulation of wealth in certain families was favored, giving them a strong position of power over the gens . The state was finally "invented" to protect family privileges. He was supposed to secure the newly created private property of the individual "against the communist traditions of the gentile order", raise it to the "highest purpose of all human community" and stamp it "with the stamp of general social recognition". In doing so he perpetuated the “division of society into classes ” and “the right of the possessing class to exploit the non-possessing and the rule of those over them”.

The form of state authority is determined by the form of the municipalities at the time when state authority becomes necessary. For example, where - as with the "Aryan peoples of Asia and the Russians" - "no private property has yet formed on the ground, state power appears as despotism ". In contrast, in the Roman lands conquered by the Germans, the individual parts of the land have already been converted into an " allod " - the "free property of the owner, subject only to the common market obligations".

The state emerged “out of the need to keep class differences in check”. But since it was created at the same time “in the midst of the conflict between these classes, it is usually the state of the most powerful economic class”. With his help, this also becomes the politically ruling class, which “thus acquires new means to hold down and exploit the oppressed class”. Exceptionally, there can also be situations where “the fighting classes are so close to one another that the state authority, as an apparent mediator, is given a certain degree of independence from both of them”. Engels mentions as examples “the absolute monarchy of the 17th and 18th centuries” - which mediated between the nobility and the bourgeoisie - and the “ Bonapartism of the first and especially the second French Empire , which played the proletariat against the bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie against the proletariat ".

Engels, however, is of the opinion that the working class still needs the state for the time being in order to overcome the power of the bourgeoisie and to be able to begin the organization of the new society. With the disappearance of society divided into classes, the state then loses its real raison d'etre. He makes himself superfluous when he is no longer the representative of a privileged class but of society as a whole. “The administration of things and the management of production processes take the place of government over people. The state is not 'abolished', it is dying ”.

nature

While Hegel viewed nature as a mere "alienation" of the idea, which is not capable of any development in time, for Engels nature is not a mere logical preliminary stage of the spirit. Rather, for him, human history is "only different from the history of nature as a development process of self-conscious organisms". Inspired by Darwin's theory of descent , Engels sees nature as a historical phenomenon.

History of science and philosophy

Engels looks at the history of the sciences primarily with regard to the development of the understanding of nature and dialectical thinking.

For the "natural materialism" of the Ionic natural philosophers , the unity and objectivity of nature was a matter of course. Because one had not yet progressed to the analysis of nature, it was still considered as a whole. For them, the “overall context of natural phenomena” was “the result of direct perception”, which reveals the “inadequacy of Greek philosophy”.

With the victory of Christianity, the cosmological-dialectical traditions of the Greeks were lost. Engels assesses the subsequent period of the Middle Ages largely negatively - as a "dark night" in which the sciences would not have developed further. Nevertheless, he emphasizes the "great progress made in the Middle Ages" - especially with regard to the "expansion of the European cultural area" and the emergence of "viable great nations".

The Renaissance was the first great epoch that was based entirely on experience. The earth was “actually only now discovered and the foundation laid for later world trade and the transition from handicraft to manufacture, which again formed the starting point for large modern industry. The spiritual dictatorship of the Church has been broken ”. However, the Renaissance was primarily concerned with the mechanics of the “earthly and heavenly bodies” and the “perfecting of mathematical methods”. This development was "brought to a certain conclusion" with Newton and Linnaeus . The special characteristic of this epoch was that it - contrary to the development approach of the Greeks - took the "absolute immutability of nature" as its starting point.

Engels sees the dissolution of this static understanding of nature only beginning with Kant's General Natural History and Theory of Heaven (1755). Kant had eliminated the “question of the first impulse” and presented the earth and the entire solar system “as something that has come into being in the course of time”. This work of Kant was ignored by the natural sciences until the appearance of Laplace and Herschel , and it was reserved for the newly emerging geological sciences to prove that “nature is not, but becomes and passes”.

The rigid system of an “unchangeably fixed organic nature” was finally dissolved by Darwin , who liquefied the concept of species. A new conception of nature was thus completed in its basic features: "Everything rigid was dissolved, everything fixed volatilized, everything that was held to be eternally special has become transient, the whole of nature has been proven to move in an eternal flow and cycle".

With Hegel, the dissolution of the rigidity of the image of nature was followed by that of concepts. Engels sees the importance of the epoch from Kant to Hegel in the rebirth of dialectics. Kant appears to him to be overtaken by Hegel. In particular, Engels opposes the undialectical Kantian interpretation of neo-Kantianism and a philosophy that sees the essence of epistemology. He describes agnosticism as a "shameful materialism".

Engels considers Hegel's system “the last, most perfect form of philosophy”; with him "the whole philosophy failed". What remained, however, was “the dialectical way of thinking and the conception of the natural, historical and intellectual world as a never-ending moving, transforming world in a constant process of becoming and passing away. The demand was now made not only of philosophy, but of all sciences, to show the laws of motion of this constant transformation process in their particular field ”.

Economy

Engels criticizes classical economics - as it was represented by Adam Smith , David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill , among others - as an "enrichment science" because it is based on private property . Their representatives were not ready to examine the "contradictions" of the existing economic conditions. The liberal economic system is to be rejected primarily because of the principle of competition on which it is based, which amounts to the “right of the strongest”. The principle of competition divides people by creating a constant conflict between buyers and sellers, and makes the trade a "legal fraud". It leads to the formation of a monopoly and leads to speculation . Engels criticizes this - based on Kant's categorical imperative - as the “culmination point of immorality” because through it “history, and in it humanity, is reduced to a means”. Ultimately, according to Engels, competition has led to the loss of human freedom : "Competition has permeated all of our living conditions and completed the mutual bondage in which people now hold themselves."

For Engels, in the capitalist economy, "all natural and reasonable relationships are upside down". Only with the abolition of private property will the natural conditions be restored and a "state worthy of humanity" created. Engels envisions a planned economy in which it is the task of the community to calculate “what it can produce with the means at its disposal and, according to the ratio of this productive power to the mass of producers, determine the extent to which it increases or decreases production, to what extent she has to give in to luxury or to limit it ”.

reception

Engels had a decisive influence on the further development of Marxism. For the labor leaders and socialist theorists he was the undisputed authority in the first years of the Second International . The most important leaders of the German, Austrian, French, Italian and Spanish labor movement ( Wilhelm Liebknecht , Karl Kautsky , Eduard Bernstein , Victor Adler , Paul Lafargue , Filippo Turati , José Mesa ) became his students and confidants. Engels' popularizations first opened up Marx's theory to broad circles of the labor movement. His writings - especially the review of Marx's On the Critique of Political Economy (1859), the late Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of classical German philosophy (1886) or the addendum to the third volume of Capital (1894/1895) - had a major impact on reception the theories of Marx and Engels. Above all, however, the Anti-Dühring became a textbook depicting a “Marxist worldview”. For Kautsky there was “no book that achieved so much for the understanding of Marxism”, and for Lenin , Engels' Ludwig Feuerbach and the Communist Manifesto were one of the “handbooks of every class-conscious worker”.

The relationship between Marx's and Engels' theory - often referred to in literature as the “Marx-Engels problem” - is controversial within Marxism. The orthodox, Marxist-Leninist tradition regards Marx and Engels as “spiritual twins” who, for practical reasons, took on various tasks. While Marx fell into the part of economics, Engels' task consisted of covering the other areas - from philosophy (Anti-Dühring) , anthropology and state theory to physics and the theory of science (dialectics of nature) . The thesis of the two "spiritual twins" has been repeatedly opposed in the literature to the thesis of the "tragic error" ("tragic deception"). According to this version, Engels misunderstood all of Marx's basic concepts and was responsible for the resulting real socialist developments. This view has been represented in particular by the “ Neue Marx-Lektüre ” since the 1970s .

The basic thesis of Engels' theory of the state that the state is a historical product is widely accepted today. The details of Engels' theory of the formation of the state are now considered outdated.

Memorial sites and honors

In numerous cities around the world (e.g. Berlin, Wuppertal, Vienna , Moscow) there are streets, squares, buildings, statues and the like named after Engels. There are references to him especially in places where Engels stayed for a long time. In Wuppertal- Unterbarmen is the historical center , which includes the property of the industrial family Engels, including the Engels house and the Engels garden with the Engels monument , inaugurated in 2014 . In London - Primrose Hill there is a plaque on a house that commemorates the stay of Friedrich Engels and his family. There is an angel house in Salford . In Manchester there is a commemorative plaque at the place where Engels once officially lived from April 1858 to May 1864: “Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) social philosopher and writer, lived at No. 6 Thorncliffe Grove, which once stood on this site ".

Mementos of Engels were made in many ways, especially in real socialism . In Berlin there is a statue of Friedrich Engels on the Marx-Engels-Forum , which was erected in 1986 by the then GDR leadership as part of the 750th anniversary of Berlin. It was also shown in the GDR on the 50- mark note. The city of Engels in Russia was named after him. There is also a statue of Engels in Dresden , which was erected there in front of a piece of the Berlin Wall after the fall of the Wall . The GDR National People's Army named its guard regiment , which was used for representative purposes, after Friedrich Engels in 1970; with central functions stationed in the Friedrich-Engels-Barracks in Berlin, in a former artillery barracks, in whose predecessor building "Guard Artillery Barracks" Engels himself was on duty. From 1959 to 1969 the coastal protection ship Friedrich Engels , a frigate of the Soviet Riga class , belonged to the People's Navy of the GDR. The NVA military academy was also named after Friedrich Engels. In 1920 the Russian destroyer Woiskowoi ( Voiskovoy / Войсковой ), built in 1904, was renamed Friedrich Engels (Фридрих Энгельс) and used on the Caspian Sea as part of the Russian Civil War. However, three years later it was renamed Markin . For this, the destroyer Desna ( Десна ) of the Orfei class was given the name Engels .

Fonts

- Letters from the Wuppertal. 1839 ( mlwerke.de )

- Cola di Rienzi . (dramatic draft, handwriting) (1840/1841)

- [Friedrich Engels]: Schelling and the revelation: criticism of the latest reaction attempt against free philosophy . Robert Binder, Leipzig 1842. Digitized

- [Friedrich Engels]: Schelling the philosopher in Christ, or the transfiguration of world wisdom into divine wisdom. For believing Christians who are unfamiliar with the philosophical use of language. A. Essenhart, Berlin 1842. Digitized MDZ reader

- [Friedrich Engels, Edgar Bauer]: The boldly troubled but wonderfully liberated Bible. Or: the triumph of faith. That is: Terrible, but truthful and considerable historia of the former licentiate Bruno Bauer; how he has been seduced by the devil, has fallen away from pure faith, has become a devil and is finally vigorously horrified. Christian hero poem in four songs. Joh. Friedr. Hess, Neumünster b. Zurich 1842. Digitized MDZ reader

- Outlines for a Critique of Political Economy. 1844 ( mlwerke.de )

- German Citizens Register , (co-author) 1844 ( mlwerke.de )

- The situation of the working class in England . Otto Wigand, Leipzig 1845 Digitized MDZ reader

- The German ideology , (with Marx) 1845 ( mlwerke.de )

- Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx: The Holy Family or Critique of Critical Criticism. Against Bruno Bauer & Consorten . Literary Publishing House (J-Rütten), Frankfurt a. M. 1845. Digitized MDZ reader

- The status quo in Germany. 1847 ( mlwerke.de )

- Principles of Communism , 1847 ( mlwerke.de )

- [Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels]: Manifesto of the Communist Party . Printed in the office of the “Education Society for Workers” by JE Burghard, London 1848 Digitalized MDZ Reader 23 pages, 1848

- The German Peasants' War. Hamburg 1850. Second impression Leipzig 1870 digitized

- Revolution and counter-revolution in Germany. New York Daily Tribune 1851 to 1852 ( mlwerke.de )

- The armies of Europe. 1855 ( mlwerke.de )

- Po and Rhine. Franz Duncker, Berlin 1859 Digitized MDZ reader

- Savoy, Nice and the Rhine. G. Behrend (Falckenberg'sche Verlagsbuchhdlg.), Berlin 1860 Digitized MDZ reader

- The Prussian military question and the German workers' party. Otto Meißner, Hamburg 1865. Digitized MDZ reader

- Reflections on the war in Germany , 1866 ( mlwerke.de )

- Brochure on "Das Kapital" by Karl Marx. First volume , 1868 ( mlwerke.de )

- The history of Ireland. 1870 ( mlwerke.de )

- The German Peasants' War. Second impression with an introduction , Expedition des "Volksstaat" (F. Thiele), Leipzig 1870 ( original edition on Google.books )

- To the question of housing. 1872 ( mlwerke.de )

- From Authority , 1872/73 ( mlwerke.de )

- The Bakuninists at work. Memorandum on the last uprising in Spain , Leipzig, November 1873 ( mlwerke.de )

-

Dialectics of Nature 1873 to 1886 ( mlwerke.de )

- therein part of the work on the ape incarnation. 1876 ( mlwerke.de )

- Mr. Eugen Dühringś upheaval in science. Philosophy, political economy, socialism . Publishing house of the Genossenschafts-Buchdruckerei, Leipzig 1878 Digitized by Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf

- The development of socialism from utopia to science , 1880 ( mlwerke.de )

- On the prehistory of the Germans. 1881/1882 ( mlwerke.de )

- The origin of the family, private property and the state . Swiss Cooperative Book Printing Company, Hottingen-Zurich 1884, 2nd edition. JHW dietz, Stuttgart 1886

- On the history of the League of Communists , 1885 ( mlwerke.de )

- Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of classical German philosophy , 1886 ( mlwerke.de )

- The role of violence in history. 1887 to 1888 ( mlwerke.de )

- On the criticism of the social democratic draft program. 1891 ( mlwerke.de )

- In the matter of Brentano versus Marx for alleged falsification of Citats. Story telling and documents . Otto Meissner, Hamburg 1891. Digitized MDZ reader

- Can Europe disarm? . Wörlein & Comp., Nuremberg 1893 Facsimile Reprint 1929 MDZ Reader

- On the history of early Christianity. 1894 ( mlwerke.de )

- The peasant question in France and Germany . November 1894 https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/marx-engels/1894/11/bauern.htm

- Introduction to Marx's Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850 . Berlin 1895. ( Archive.org )

Work editions

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Works. ( MEW = M arx- E ngels- W erke; also known as blue volumes ). 44 volumes, Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1956–2018 Letters in volumes 27 to 39 and 41

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Complete Edition. ( MEGA = M ARX E ngels- G otal a ssue). Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1975 ff. / Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1998 ff.

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Selected works in two volumes . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1951 (34th edition Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1989)

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Selected works in six volumes . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1970 (8th edition 1979) (licensed edition Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1970)

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Selected Works . Digital Library Volume 11 ( CD-ROM ), Directmedia, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-932544-15-3 .

- Friedrich Engels: Selected military writings . Selected and compiled by Günter Wisotzki, Vol. 1 Berlin (Publishing House of the Ministry of National Defense) 1958, Vol. 2 Berlin ( German Military Publishing House ) 1964.

Correspondence

- Letters from Ferdinand Lassalle to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels 1849 to 1862. ed. by Franz Mehring . JHW Dietz Nachf. (GmbH), Stuttgart 1902

- Letters and excerpts from letters from Joh. Phil. Becker , Jos. Dietzgen , Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx a. A. to FA Sorge and Others . JHW Dietz successor, Stuttgart 1906

- Correspondence between Engels and Marx . Edited by August Bebel and Eduard Bernstein. 4 vols. JHW Dietz Nachf., Stuttgart 1913

- Gustav Mayer (ed.): The correspondence between Lassalle and Marx. Along with letters from Friedrich Engels and Jenny Marx to Lassalle and from Karl Marx to Countess Sophie Hatzfeld . German publishing company; Publishing house Julius Springer, Stuttgart, Berlin 1922 (Ferdinand Lassalle. Post-mortem letters and writings. Ed. By Gustav Mayer. Third volume)

- Victor Adler's essays, speeches and letters . Edited by the executive committee of the Social Democratic Workers' Party in German Austria. First issue: Victor Adler and Friedrich Engels. Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, Vienna 1922

- Karl Marx Friedrich Engels. Letters to A. Bebel, W. Liebknecht, K. Kautsky and others. Part I. 1870-1886 . Obtained from the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute Moscow, edited by W. Adoratski. Publishing Cooperative of Foreign Workers in the USSR, Moscow-Leningrad 1933

- Antonio Labriola . Lettre a Engels . Rome 1949

- Friedrich Engels' correspondence with Karl Kautsky . Second edition of "From the early days of Marxism", completed by Karl Kautsky's letters. Edited and edited by Benedikt Kautsky . Danubia-Verlag, Wilhelm Braumüller University Bookstore, Vienna 1955 ( Sources and studies on the history of the German and Austrian labor movement, Vol. I. Ed. By the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam)

- Friedrich Engels Paul and Laura Lafargue . Correspondance . Texts recueillis, annotés and présentés by Émile Bottigelli. Traductions de l'anglais par Paul Meier. 3 Vols. Édition Sociales, Paris 1956–1959

- Georg Eckert (Ed.): Wilhelm Liebknecht. Correspondence with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . Mouton & Co., The Hague 1963 ( Sources and studies on the history of the German and Austrian labor movement V. International Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam)

- Karl Marx Friedrich Engels correspondence with Wilhelm Bracke (1869–1880). On behalf of the Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED ed. and introduced by Heinrich Gemkow. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1963 (Library of Marxism-Leninism Volume 62)

- La correspondentia di Marx i Engels con italiani. 1848-1895 . A cura di Giuseppe Del Bo. Milan 1964

- The First International in Germany (1864–1872). Documents and materials . Editors Rolf Dlubek , Evgenija Stepanova, Irene Bach, Ursula Hermann, Erich Kundel, Vera Morosova, Olga Senekina, Richard Sperl. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1964

- Werner Blumenberg : August Bebel's correspondence with Friedrich Engels . Mouton & Co., London The Hague Paris 1965 ( Sources and studies on the history of the German and Austrian labor movement VI. Ed. Internationaal Instituut voor sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam)

- Herbert Steiner : The Scheu brothers . In: Archive for Social History Vol. VI / VIII, 1966/67, pp. 441-576.

- Freiligrath's correspondence with Marx and Engels . Edited by Manfred Häckel. 2 parts. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1968 (published by the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin Institute for German Language and Literature)

- The Harney Papers . Edited by Frank Gees Black and Renee Métiver Black. van Gorcum & Comp., Assen 1969 (Publications on Social History issued by the Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis V.)

- Helmut Hirsch (ed.): Eduard Bernstein's correspondence with Friedrich Engels . van Gorcum & Comp. NV, Assen 1970 ( Sources and studies on the history of the German and Austrian labor movement. New series vol. 1. Ed. V. Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam)

- Friedrich Leßner : I took the “Communist Manifesto” to the printer . Compiled and introduced by Ursula Hermann and Gerhard Winkler with the assistance of Ruth Rüdiger and Wilfried Henze. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1975

- Contemporaries of Marx and Engels. Selected letters from the years 1844 to 1852 . Edited and annotated by Kurt Koszyk and Karl Obermann . Van Gorcum & Comp, Assen / Amsterdam 1975 ( Sources and studies on the history of the German and Austrian labor movement. New series Vol. VI. Ed. V. Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam)

- Heinz Monz : The connection between Paul Stumpf from Mainz and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. At the same time a contribution to the history of the Mainz labor movement, Darmstadt 1986 (Hessian contributions to the history of the labor movement)

- Jan Gielkens: “We're moving tomorrow”. A previously unpublished postcard from Friedrich Engels to Karl Kautsky. For Götz Langkau . In: Ursula Becker, Heiner M. Becker, Jaap Kloosterman (editor): No obituary! Articles about and for Götz Langkau. IISG, Amsterdam 2003, pp. 98-100.

- Markus Bürgi: Friedrich Engels and his relatives Beust in Zurich. Newly found letters and materials relating to a previously unknown relationship . In: Marx-Engel-Jahrbuch. 2006, Berlin 2007, pp. 171-213.

- Gerd Callesen: Victor Adler - Friedrich Engels correspondence. Vienna 2009 (Association for the History of the Labor Movement. Documentation 1–4 / 200)

Excerpts

- ( Brochure ): G. von Gülich - Germany . In: Karl Marx Friedrich Engels. About Germany and the German labor movement. Volume 1. From the early days to the 18th century . 6th edition. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1978, pp. 521-561.

- Artillery from America . In: Friedrich Engels 1820–1970. Papers discussions documents . Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen, Hannover 1972, pp. 69–71.

- Hans-Peter Harstick : Friedrich Engels marrow constitution of primeval times . In: Friedrich Engels 1820–1970. Papers discussions documents . Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen, Hannover 1972, pp. 261–289.

See also

literature

Biographies and Biographical Literature

(chronologically)

- Karl Kautsky : Friedrich Engels. His life, his work, his writings . 2nd edition, Vorwärts, Berlin 1895.

- Friedrich Engels . In: Emanuel Wurm : Volks-Lexikon. Reference book for all branches of knowledge with special consideration of workers' legislation, health care, commercial science, social policy. Fourth volume. Wörlein & Comp., Nuremberg 1897, pp. 432-433.

- Gustav Mayer : Friedrich Engels. A biography. Vol. 1: Friedrich Engels in his early days 1820–1851 . Springer, Berlin 1920.

- Ernst Drahn : Friedrich Engels. A picture of his 100th birthday . Vienna / Berlin 1920.

- Max Adler : Engels as thinkers . Berlin 1920.

- JB Mayer: Friedrich Engels. A demolition . Trier 1931.

- Walther Victor : The general and the women . Book guild Gutenberg, Berlin 1932 (new edition Hammerich & Lesser, Hamburg 1947) story .

- Gustav Mayer: Friedrich Engels. A biography. Vol. 1: Friedrich Engels in his early days. Vol. 2: Engels and the rise of the labor movement in Europe. Martinus Nijhoff, Haag ² 1934/1934. Reprint: Ullstein, Frankfurt / M. Berlin / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-548-03114-5 (The most comprehensive Engels biography to date).

- Reinhart Seeger: Friedrich Engels as a “young German” . Inaugural dissertation. Eduard Klinz book printing workshops, Halle (Saale) 1935.

- Auguste Cornu : Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Life and work. 1818-1846 . 3 vols., Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1954–1968.

- EA Stepanowa: Friedrich Engels. His life and work . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1958.

- Wolfgang Köllmann : Friedrich Engels . In: Wuppertal Biographies 1st episode. Contributions to the history and local history of the Wuppertal , Volume 4, Born-Verlag, Wuppertal 1958, pp. 35–39.

- Hermann Dollnow: Engels, Friedrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , pp. 521-527 ( digitized version ).

- Věra Macháčková: The young angel and literature (1838–1844) . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1961.

- Horst Ullrich: The young angel . 2 parts, Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1966.

- Helmut Hirsch : Friedrich Engels in personal testimonies and photo documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1968; 11th edition, 2002, ISBN 3-499-50142-2 (= Rowohlt's monographs , volume 142)

- Helmut Hirsch: Friedrich Engels (1820–1895). In: Rheinische Lebensbilder . Volume 4. Edited by Bernhard Poll . Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1970, pp. 191-208.

- Heinrich Gemkow (among others): Friedrich Engels. A biography. Dietz, Berlin 1970 (6th edition 1988), ISBN 3-320-00308-9 .

- Friedrich Engels. 1820-1895. Life and work. An exhibition of the city of Wuppertal , arr. v. Dieter Dowe . Research institute of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation with a previously unpublished letter from Friedrich Engels. Bonn – Bad Godesberg 1970.

- Harald Wessel : House visit to Friedrich Engels. A journey on his life path . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1971.

- Hans-Josef Steinberg : Friedrich Engels . In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler German Historians , Volume 3, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, pp. 263–274.

- LF Ilyichov: Friedrich Engels. His life and work . Progress, Moscow 1973.

- Hans Pelger, Michael Knieriem (ed.): Friedrich Engels as the Bremen correspondent of the Stuttgart “ Morgenblatts für educated readers ” and the Augsburger “ Allgemeine Zeitung ”. Trier 1975 (= writings from the Karl-Marx-Haus Trier , issue 15) (2nd extended edition 1976).

- William Otto Henderson: The Life of Friedrich Engels. 2 vols., London 1976, ISBN 0-7146-4002-6 .

- Manfred Kliem : Friedrich Engels. Documents of his life . Reclam, Leipzig 1977. Digitized

- Terrel Carver: Angels . Oxford University Press, Oxford / Toronto / Melbourne 1981 (Past Masters).

- Hans Peter Bleuel : Friedrich Engels - Citizen and Revolutionary. The contemporary biography of a great German . Scherz publishing house. Bern / Munich 1981 novel .

- Walter Baumert : The flight of the falcon. The rebellious youth of Friedrich Engels . Junge Welt, Berlin 1981 (also Weltkreis-Verlag, Dortmund 1981, ISBN 3-88142-257-9 ) Roman .

- Heinrich Gemkow: Our life. A biography about Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1981.

- Their names live on through the centuries. Condolences and necrologists on the deaths of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Editors Heinrich Gemkow and Alexander Malysch, Anny Krüger, Boris Rudjak , Olga Senekina, Günter Uebel, Holger Franke, Gisela Hoppe, Angelika Miller, Alexander Tschepurenko and Lujudmilla Welitschanskaja . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1983.

- Frederick Engels. His Life and Works. Documents and Photographs. Translated by Vic Schneiderson. Designed by Victor Christyakov. NN Ivanov, TD Belyakova, YP Krasavina. Introduction NN Ivanov. Edited by VE Kunina . Progress Publishers, Moscow 1987.