Reineke Fuchs

Reineke Fuchs is the main character of an epic in verse and prose, the tradition of which goes back to the European Middle Ages. A Low German version Reynke de vos , printed in Lübeck in 1498, developed into a bestseller in the German-speaking countries in the 16th century. It tells how the culprit Reineke, the fox , saves himself from all precarious situations through ingenious stories of lies and selected malice and ultimately prevails over his opponents.

The High German editions that had already been made since the 16th century , in particular the prose transmission by Johann Christoph Gottsched in 1752, passed on the story in its centuries-old German-language version almost unchanged to the present day. The work and its eponymous hero have inspired translators, writers and illustrators since the mid-16th century. The name form Reineke Fuchs , which is in use today , was last established through the epic verse epic by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe .

The story of Reineke

content

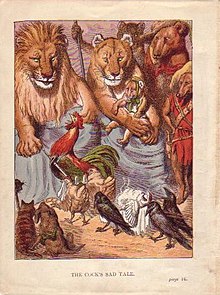

The story, which has been handed down in print since the late 15th century, consists of two parts, each of which tells of a court case. Nobel the lion, king of the animals, has invited to the court day at Pentecost. Those present, big and small, especially Isegrim the wolf, complained about the misdeeds of the fox Reineke, who was not present, and demanded that he be punished. Braun, the bear, and Hinz, the cat, are sent one after the other to bring Reineke from his castle Malepartus to the court. Both fail, Reineke deliberately puts her life in danger, and, badly maltreated, narrowly escapes death.

The king takes the shame personally and has Reineke's appearance in court. The verdict is death. Under the gallows, his head already in the noose, Reineke succeeds in inventing a tale of lies disguised as a confession of treason and treasure, which declares the bear Braun and the wolf Isegrim high traitors and makes Nobel the lion greedy. Reineke is released and sets off on a pilgrimage to Rome and away. Reineke's betrayal is revealed after he has sent the bitten off head of his pilgrim companion, Master Lampe , the hare, back to the king. Braun and Isegrim are rehabilitated by Nobel's grace.

After Grimbart, the badger, has brought Reineke back to the court, a second court hearing develops, in which further atrocities of Reineke come to light and are dealt with in speeches by the prosecution and the defense. Reineke refers to all kinds of benefits his family did at court, in particular to the rescue of Nobel's sick father by his own. Isegrim's accusation, however, that Reineke had violated his wife Gieremund, prompted Nobel to decide to let Isegrim and Reineke compete against each other in a public duel. For the fox this means the second death sentence, because he is physically inferior to the wolf. Reineke wins by incapacitating the wolf with painful unsportsmanlike conduct. This convinced the audience and prompted King Nobel to appoint Reineke as his councilor and chancellor of the empire.

features

The fox's tower of lies has a condensation of its hypocrisy, malice and acts of violence, from which the duel is consequently developed in the end, similar to the so-called showdown of classic film genres. The inner structure of the narrative consists of a combination of episodes which increase the plot, in which the fox is confronted with opponents or situations that are challenging for him; The episodes are also used for internal narratives , which - such as in the indictment and defense speeches or on the occasion of Reineke's confessions - not only serve to intensify the present story, but also allow the participants to different perspectives on Reineke's acts. Since the 15th century the text has been divided into chapters and books.

The animals in the Reineke Fuchs are anthropomorphic creatures; they are individualized by proper names and endowed with human characteristics. In their actions, the characters follow their animal nature on the one hand and the rules of human coexistence on the other. The event thus contains motives that are common to all living beings, such as the search for food or the flight from persecution, as well as elements of a purely human order, such as adultery or the forms of indictment and defense before a court. The characters decisive for the plot, especially Nobel, Braun, Reineke and Isegrim, are characterized by vanity, stupidity, cunning and greed; these traits are continued in the numerous secondary characters and their fates and expanded into a panopticon in which the human tragedy of power, violence and death is designed as an animal comedy .

The fox epics of the Middle Ages

"The clever fox" can be found in the legendary circles of those parts of the world where Vulpes , the fox, is at home, such as Eurasia , North America and the Mediterranean . In Europe he appeared in ancient literature. One of Aesop's fables tells of a fox healing a sick lion; the origin of Reineke is assumed there. In the European Middle Ages, animal tales with a fox can be found throughout, for example the Latin fables of Phaedrus , Babrios and Avianus, inspired by Aesop, circulated in the manuscripts. Since the 12th century, the fox has also appeared as a supporting figure, appearing as Reinardus , Renart , Reinhart , Reynaert or Reynard with a speaking name, a composition of regin - (= advice) and - hard (= strong, bold).

The Reinardus of the Latin Middle Ages

The first literary version in epic length in which the fox plays a role is the Ecbasis captivi , a satire in Latin from St. Evre near Toul from around 1040, which tells of a day of judgment of the lion with complaints against the fox .

An unknown author from Ghent , perhaps Nivardus , is attributed the Ysengrimus , an animal poem in Latin that was completed in 1148 and in which the wolf Ysengrimus (also Isengrimus , Ysengrinus and Isengrinus in the manuscripts ) plays the main role and constantly clashes with his opponent Reinardus , the Fuchs, has to deal with it. The two animals here for the first time bear the names with which they are identified in all later texts. The epic is a satire on the monk class; Ysengrimus is the monk, his adversary Reinardus the layman . The work, of which an abridged version from the 14th century, the Ysengrimus abbreviatus , has survived, received little attention in the 15th century; his allusions and polemics were now out of date.

The Reinhart in the vernacular languages of the Middle Ages

The handwritten text traditions show that Reineke's story about the collections of individual animal stories and their amalgamation increasingly condensed in the various vernacular languages of the European Middle Ages into a literary composition that transcended language borders. The Low German version printed in 1498 was based on Dutch versions of French origin.

Roman de Renart

Between 1170 and 1250, the Roman de Renart was written in the vernacular in northern France : The clever fox Renart triumphs in numerous episodes over a strong lion ( Noble ) and a stupid, greedy wolf ( Ysengrin ). The novel consists of so-called branches of different authors, the number and arrangement of which vary in the 20 traditional manuscripts and fragments and which together comprise about 25,000 verses. The individualization of animals through proper names appears increasingly pronounced in the branches . The stories show features of the courtly world, whose representatives and their actions are parodied by the mixing of human and animal behavior ; Renart is a baron revolté who is constantly endangering the power of the king of the beasts, the lion noble . The story told in branche XI is seen as fundamental to the expansion of the subject in the 13th century; it is about how Renart seduces the lioness while Noble is on a crusade.

As early as the 12th and 13th centuries, the Romance- speaking area had an abundance of fox poems and developed its own successful tradition. The Renart le bestourné by Rutebeuf , comprising over 8000 verses, appeared around 1261 , Le couronnement de Renart was published around 1270 , followed by the Renart le nouvel by Jacquemart Gielée with 8048 verses in 1289 , and in the first half of the 14th century. Century finally the Renart le contrefait with about 40,000 verses. Relevant for the Low German Reynke of 1498, however, was only the Roman de Renart , which also influenced the old French language in the Middle Ages: the name of the fox as goupil was replaced by the name renart and forgotten.

Reinhart Fuchs

Heinrich (called der Gleißner ) from Alsace wrote the Middle High German Reinhart Fuchs at the end of the 12th century . Some parts of the epic verse make it clear that they are based on the novel de Renart , whose cyclical-episodic structure is, however, put into a linear, increasing plot. The story shows features critical of society and, as a warning satire, expressly takes a stand against the Hohenstaufen people . Heinrich delivers an idiosyncratic punch line: the fox poisons the lion at the end.

The work is the only German-language animal poem from this period, evidenced in three manuscripts from the 13th and 14th centuries. It did not receive any further edits from other authors. In the early days of printing, Reinhart Fuchs was not widely used; he was rediscovered in the 19th century by Jacob Grimm .

Reynaert's history

In the 13th century a Flemish named Willem wrote a Middle Dutch version of Van den vos Reynaerde , in which traces of the Roman de Renart can also be found. Willems version tells of the lion's court day, the charges against the absent fox and how he cheats on the two messengers bear and cat. It ends with the death sentence against the fox and his invention of the story of lies, with which he pulls his head out of the noose, as well as his promise to make a pilgrimage to Rome and his subsequent betrayal. In contrast to the more instructive Reinhart Fuchs , Willem's work is characterized by unrestrained narrative joy and an accumulation of fluctuating ideas. Perhaps provoked by the open ending - the rehabilitation of Bear and Wolf after Reineke's Hasenkopf betrayal - the work was revised by an unknown author around 1375, who considerably expanded the narrative as Reynaert's history and built up the structure of the two-time court proceedings. The two verses are now known as Reynaert I and Reynaert II . The Willems version became Dutch national literature; the town of Hulst , mentioned in the epic, has erected a monument to the Reynaerd .

Further edits

In the early days of book printing, Reynaert II was edited twice, including one in prose, printed by Gerard Leeu in Gouda in 1479 under the title Historie van reynaert die vos , which was reprinted in 1485 by Jacob Jacobsz van de Meer in Delft . The other, a version in verse with prose comments, was published in Antwerp between 1487 and 1490 , again printed by Gerard Leeu, who in the meantime had moved his publishing house there. This constitution is only preserved in seven intact sheets.

From the Netherlands, Reynaert also found his way into England as Reynard and established his own text history there; Effects on the continental development of the substance have not been clearly demonstrated. In 1481 William Caxton printed The History of Reynard the Fox , an English translation of the Dutch prose version of the Gouda edition by Geeraert Leeu.

A printed translation of Reynaert II into Low German with a Reynke as the protagonist passed on this late medieval Dutch story in its content, structure and staff to this day through the distribution of its reprints and translations.

The Lübeck print from 1498

In 1498, Hans van Ghetelen published the work Reynke de vos in his poppy-head printer in Lübeck , a Low German poem in 7791 creased verses rhymed in pairs, the chapters of which were divided into four books of different lengths, two of which were provided with prose introductions. The individual chapters were given glosses in prose, which commented on the events for the reader's everyday life and which are now referred to as “Catholic glosses”. The edition was richly illustrated with 89 woodcuts .

The story of Reynke , whose name is the Low German diminutive of Reynaert or Reinhart , takes place in Flanders , as can be seen from a few references in the text, such as the city of Ghent ; In addition, Hinrek von Alckmer, whose name can also be assigned to the Dutch-speaking area, reported in the foreword as the mediator and editor of the story. His name as the author as well as the details of his person have only survived from this print and the authorship was disputed as early as the 19th century; A priest from Lübeck, unknown by name, was suspected to be the processor. It is not known which model the Lübeck print is based on. However, it can be considered certain that the template used ultimately goes back to the Reynaert II .

The print is only completely preserved in a single incunabulum , which is in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel . Nevertheless, he justified the further tradition of Reineke in German-speaking countries in the history of his reprints and their reception.

From the incunable to the folk book

Based on the Lübeck print of 1498, the Low German verse story by Reynke de vos spread to other print sites in the 16th century; in addition, it achieved international sales through its translation into Latin. The story reached the entire Scandinavian-speaking area via Lübeck and became a popular book in Northern Europe .

The editions of the 16th and 17th centuries

The Lübeck Reynke de vos was reprinted in Rostock in 1510 and 1517 . The first reprint has not survived; the second from 1517 contained only 30 woodcuts and had a significantly smaller number of leaves than the Lübeck incunabulum. The time gap between the editions was relatively large in view of the sales opportunities for book publications in the Hanseatic city. This and the significantly reduced scope of the traditional reprint led to the assumption in recent research that the story initially did not receive a notable reception by the public.

Distribution of the Low German Reyneke Vosz

The real success story of Reynke de vos began in 1539 with an edition again printed by Ludwig Dietz in Rostock with the title Reyneke Vosz de olde , which had now been provided with considerably expanded comments (the so-called "Protestant gloss"). The Low German Reyneke Vosz experienced eleven additional editions in Rostock, Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg from 1549 to 1610 . The editions differed in format and features. In 1550 , the Frankfurt printer Cyriacus Jacob published an expensive volume in quarto format , which, however, dispensed with the chapter glosses and therefore managed with 150 sheets. Also in Frankfurt, Nikolaus Bassée published a Reyneke print as a cheap octave ; the prints of the Hamburg-born Paul Lange from 1604 and 1606 as well as a later descendant of the Low German Reyneke , in 1660 at Zacharias Dose in Hamburg, followed this format.

Standard German and Latin editions

Even before the Rostock edition of 1549, Cyriacus Jacob had published a print in folio format in Frankfurt in 1544 with the title Von Reinicken Fuchs , a High German translation of Reyneke Vosz , which was probably written by Michael Beuther and which subsequently made Frankfurt the most important place of printing for the Reineke tradition; By the beginning of the Thirty Years' War , 21 High German, five Low German and seven Latin editions were published here. Hartmann Schopper provided the first translation into Latin based on the High German version. It was published in 1567 by Sigmund Feyerabend and Simon Huter in Frankfurt am Main under the title Opus poeticum de admirabili fallacia et astutia vulpeculae Reinikes , a poem about the foxish intrigue and cunning of the remarkable Reinike , and contained a dedication ad divum Maximilianum secundum , the divine emperor Maximilian II . The edition was reprinted until 1612. In 1588 a Latin-High German adaptation by Joseph Lautenbach was printed under the title Technae aulicae / Weltlauff vnnd Hofleben .

Translations

Since its second edition of 1574/75, Schopper's Latin edition was subtitled Speculum vitae aulicae , Mirror of Court Life . In the 17th century it became the occasion for translations into various national languages, such as, for example, into English, where Reineke was in competition with a text tradition of its own that had existed since the edition of Caxton in 1481, and into Spanish. The spread of Reineke in the Scandinavian-speaking area was initially followed by the Low German Rostock edition of Reyneke Vosz from 1539; a first Danish translation was published in Lübeck in 1555. In Stockholm , Reineke was published in Swedish in 1621, based on a Latin edition printed in Hamburg in 1604; an English translation from 1706 also followed this Hamburg version.

Folk books

In 1650, a poetically free adaptation of the High German Frankfurt version was published, which was reworked into prose at the end of the century and had several editions. Der cunning Reineke Fuchs and Des cunning Reineke Fuchs based life and boys pieces on the baroque version, printed in Hamburg by Thomas von Wiering between 1690 and 1700. Reineke had become a popular book, the material for free designs that promised sufficient prospects of commercial sales and mostly came onto the market as “first prints”.

Illustrations

The incunabulum from 1498 contained 89 woodcuts, which were also colored for some editions . The expensive presentation indicates that the print should be sold from the wealthy Lübeck stalls. The pictures show the pair of lions always in Herrscherornat , however, the animal subjects retain their nature, whose character tried to express the designer in differentiated Schnittschraffuren; for his role as a monk, however, the fox is put on a habit. A special form of the Lübeck edition are the so-called Dialogus woodcuts, which introduce the second book as an interlude in the form of a conversation between the animals that glosses over the events. The depictions of animals here are designed in a more minimalist way than in the illustrations of the plot and gain emblematic character through their connection with the text .

For the Rostock edition of 1539, Erhard Altdorfer , court painter in Schwerin , designed a new series of woodcuts which, by refining the cut, unfold and enhance the expression of the figures in their surroundings. The series illustrated the other Rostock reprints of the 16th century. In other printing locations it was copied and cut; the images appeared reversed and the details were clearly varied. The Low German and Latin editions, which had appeared in the octave format that was now predominant since the end of the 16th century, received new, small-format woodcuts; this series appeared in prints up to Zacharias' Hamburg edition in 1660.

Comments

In the long history of his prints, Reineke was accompanied by glosses that document a clear change in the intentions of the respective editors to prepare the almost unchanged text in its reading for the public.

The Catholic glossator of the 1498 edition is clearly aimed at an urban audience. He tries to hold up a mirror of sins to the reader by presenting the story in the sense of a fable and its interpretation and working out the fox as a figura diaboli . Although he also criticizes the Church, he nevertheless warns against as a layman accusing a clergy of bad things. The comments support the assumption that the editor of the Lübeck version was a clergyman from the religious circles of the city.

The Protestant glosses of the Rostock print of 1539 express a clearly changed view; they basically target the church, papacy, monastic life and ecclesiastical law. For example, the editor not only criticizes the useless life of the nuns (1st book, 18th chapter), but also castigates indulgences , pilgrimages and the ecclesiastical ban procedure (1st book, 29th chapter) and thus underlines his Reformation standpoint. Likewise, in the fundamental nature of his comments, he turns against the grievances of his time, for example against the practice of sneaking into positions at court through “gifts” or “van übler art” (book 1). "As such, as a criticism of the old church and social conditions, the poetry unfolded its full effect and won the favor of the public."

The High German version published by Cyriacus Jacob in Frankfurt in 1544 shows a further tendency to illuminate Reineke's poetry . In the title ( Ander Teyl Des Buchs Schimpff un [d] Ernst [...] ), this edition refers to another popular book of the time: Schimpf und Ernst by Johannes Pauli . In his “Preface to the Reader”, the High German editor states that he intends to deal with his predecessors, who intend to shorten their comments and also want to remain anonymous. His comments show literary ambitions, for example by occasionally contributing a poem instead of a commentary, thus opening up the possibility already indicated in the title of allowing the reader, through the manner of allusion, to feel addressed by his criticism or not.

Even if the commentaries in their tradition, based solely on their size, seem to cover up the text rather than reveal it, they illustrate the particular suitability of the narrative for confrontations with social realities as well as with a respective opponent; The extraordinary success of the history of Reineke since the 16th century is therefore attributed in particular to its glosses.

From the folk book to the heroic epic

In 1711 Friedrich August Hackmann reissued the epic in the version of the Lübeck print of 1498 in Wolfenbüttel with the title Reineke de Vos with the Koker, with the intention of contrasting the baroque tone of the 17th century arrangements with the original version; the title copper showed a fox with a quiver and arrow in front of King Nobel. Hackmann had already given lectures on Reineke Vosz as a professor in Helmstedt in 1709 , allowing himself insubordinate statements against notables and mocking religion, which, as a result of a lecture ban and the Consilium abeundi , the advice to leave , earned him: he became the town referenced. Forty years later, Hackmann's edition became the template for Johann Christoph Gottsched's prose transmission.

Gottscheds Reineke the fox

Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766), scholar and one of the most influential figures in literary life in the 18th century, was also an expert on old German literature. In 1752 he published a prose version of the animal poem under the title Reineke the Fox at Breitkopf in Leipzig and Amsterdam . In addition to Hackmann's edition, he also used the Frankfurt verse translation into New High German from 1544 as a template.

Gottsched retained the division into four books, prominently emphasized "Heinrich von Alkmar" in the title and added the Low German version from 1498 in the appendix, albeit without their comments. His prose version is preceded by Hinrek's preface by Alkmer from 1498 and that by Nikolaus Baumann from the Rostock edition of 1549; The "Alkmarische" and the "Baumannische Notes" are added to the individual chapters. In his own introduction, Gottsched also provided a “historical-critical examination” in which he reported on the basis of a collection of sources “From the true age of this poem” (Section II) and also bibliographically recorded the previous “editions and translations” (IV . Section). In contrast to the prose versions already available, which he found neither to be true to the text nor to be “read everywhere without disgust and reluctance”, he said, “Reineke should be snatched from the hands of the mob” and “back in to lay the hands of the noble, clever and witty world ”.

The edition was illustrated with 57 etchings by the Dutch painter and graphic artist Allart van Everdingen . They show the animals in their natural environment of the landscape and the associated human dwellings, but without attaching human insignia to them; their position in the power structure of the narrated story is made clear solely through the expression and movement of the animals. Similar to the woodcut series of the 15th and 16th centuries, the fox only wears a habit when appearing as a monk.

Goethe's Reineke Fuchs

In January 1793, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) began to edit Reineke Fuchs in verse, which he completed in April. At the end of the same year the work went to print and appeared in the spring of 1794 as the second volume of the Neue Schriften by Joh. Friedr. Unger in Berlin . It consists of 4312 verses in hexameters , divided into twelve chants , and contains no commentary.

The model for the animal poem was Gottsched's prose version from 1752, which Goethe had known since childhood. Goethe also owned 56 etchings from the Reineke-Fuchs series Allart van Everdingens, which he had acquired at an auction in 1783. Goethe's correspondence with Breitkopf-Verlag in 1782 regarding Allart van Everdingen's printing plates suggests that Goethe also knew the Delft edition of the Historie van reinaert die vos from 1485 when he was writing his Reineke Fuchs .

Apart from the linguistic form and the new classification, Goethe stuck closely to the template. As he himself said, he wrote the hexameters “by ear”. The ancient form of the long verse of the Homeric heroic epics had attracted attention in the German language, in particular through Klopstock's Messiah (since 1748), but also through the current Homer translations by Stolberg (1778) and Voss (1781), but was considered a form of expression for serious or solemn topics . Goethe's use, however, had a playful character, as he did not count the verses and freely designed the caesuras in favor of the accuracy of the expression. The casualness of this style robs the story, which Goethe described as the “unholy world Bible”, of all teaching and allegorical aspects .

The Reineke cycle of Wilhelm von Kaulbach

The publisher Johann Georg Freiherr Cotta von Cottendorf (1796–1863), whose house, the Cotta'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung in Stuttgart , had become the most important publishing house of the classics and had also published Goethe's works since 1806, had begun a series of large-format editions Issue individual editions on which the Munich artist Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1804–1874) collaborated. In 1840 Cotta signed a contract with the artist to design the illustrations for a new edition of Goethe's Reineke Fuchs . Kaulbach, who worked long-term with his own monumental paintings in the studio, worked for three years in the evenings on the relatively high-value commission and delivered 36 main pictures and numerous vignettes . The drawings were engraved in copper by Hans Rudolf Rahn in Zurich and Adrian Schleich from Munich ; In 1846 the book appeared in folio format , bound in red or blue leather with gold-colored blind embossing .

During the three years Kaulbach had increasingly discovered his drawings on Reineke as a vehicle for his personal examination of the developments of his time; In all sorts of allusions to the contemporary accessories of the figures or the details on the margins, he mocked nouveau riche demeanor, occasionally targeted a politician or made fun of the Biedermeier zeitgeist, which he considered foolish ; For example, a plaque at Reineke's Malepartus Castle shows a jumping figure, only visible in the lower half, with an antique skirt, which is dousing a burning house with a water jug; underneath the inscription: "Saint Florian , protect this house and set it on fire". King Nobel already wears his tail pulled through his buttonhole in a domestic bedroom scene.

For Wilhelm von Kaulbach, the Cotta edition was a lasting success; the book came out again in 1865. For the publisher, however, a smaller edition published in 1857 turned out to be a gold mine; it received several editions, albeit no longer dated. Kaulbach's drawings appeared in a wood printing process developed in the 19th century for mass production ; they increased Reineke's popularity and also attracted sustained attention to the epic, which the Goethe exegetes regarded as the master's inde- pendent work and which was therefore less appreciated.

Reineke as baron revolté

Cotta had been uneasy about Kaulbach's work at the occasional insight into its progress; He was also the publisher of a widespread Allgemeine Zeitung and feared its ban by the Bavarian Minister Karl von Abel . The artist acknowledged this concern with a final vignette, which shows the gripping of the publishing house as a governess surrounded by moths . In retrospect, Cotta's fears do not seem unjustified. In the same year as Kaulbach- Reineke , a Neuer Reineke Fuchs by the Berlin author Adolf Glaßbrenner was published in 1846 ; The work narrowly escaped censorship and is today one of the most important social satires of the Vormärz .

The trace of Reineke as the baron revolté , the rebellious nobleman who was once embodied by the old French Renart , had already been taken up by German-speaking writers in their own, free adaptations at the end of the 18th century, inspired by the French Revolution and by Goethe's verse transmission. A Reineke Fuchs at the end of the philosophical century was written by an unnamed author , supposedly published in Itzehoe in 1797 . In fact, this work was from Altona and portrayed the Danish King Christian VII as a cocoa-drinking idiot. In 1844 Der neue Reineke Fuchs appeared in eight philosophical fables , a satire on Schelling's philosophy ; In 1871, Reineke had to storm in relation to the war events of 1870/71 . In 1872, the Luxembourgish writer Michel Rodange, in his version of Goethe's version, transferred Reineke as Renert or de Fuuss in tailcoat an a Maansgréiss to the current conditions in his country, using regional dialects.

From heroic epic to children's book

The romantic reception of the Middle Ages in the first half of the 19th century resulted in re-editions of the folk book with the story of Reineke, for example the edition by Karl Simrock in the first volume of his German folk books from 1845. A rewrite in 1803 in romantic-looking Knittel verses by Dietrich Wilhelm Soltau had several editions up to 1830. With the mass production of books from the 1840s onwards, in addition to the editions of fragments and previously unknown text witnesses, which were largely recognized by academia, editions, some of which were shortened, also increasingly appeared on the market for a wide audience; The glosses were omitted throughout, so that these have largely disappeared from the awareness of the general readership today.

In the 20th century, Reineke not only found artists again, such as A. Paul Weber and Josef Hegenbarth , who illustrated his story, but also entered the now international stage. The opera Le Renard by Igor Stravinsky was written in 1915 . Since the 1960s, Reineke conquered the speaking stage, mainly in adaptations of the Goethe version. One of the most successful productions by Reineke Fuchs was that of Michael Bogdanov at the Hamburger Schauspielhaus , which remained in the program for several years from 1987.

An adaptation by Friedrich Rassmann, which was shortened and cleaned up in 1820, paved the way for children's books, which had been part of the publishing program since the middle of the 19th century. The old story was now increasingly set up for the young reader as well, consistently for his instruction; the episodes of the traditional epic and its popular book version sometimes appeared as individual fables. As a result, Reineke not only served as an upbringing, but was also prepared for propaganda purposes for the children ; Between 1937 and 1941 in the Netherlands, for example, the edition Van de vos Reynaerde by Robert van Genechten was published, an anti-Semitic children's book that was made into a film in 1943 with money from the National Socialists. In 1961 Franz Fühmann wrote a Reineke Fuchs for young readers in prose based on an edition of the translation from the Low German by Karl Simrock (1852) and a Low German version. In a comment published 20 years later, Grausames vom Reineke Fuchs , he complained that he had falsified the original in some places out of “prudish”. Another edition of the story for children, edited and illustrated by Janosch , found its audience since 1962.

An edition in Latin for grammar school classes had already appeared in 1890. In the forms of children's books, Reineke also made it into the reading books, but mostly only in excerpts from the old story. Reineke's more recent German books have often restricted them to individual motifs under the keyword fable , such as the so-called fountain adventure already told in de Renart's novel : the fox frees himself from a fountain by luring the wolf into it and letting it hang in the bucket .

Research history

Since the 19th century, two aspects of the philological research of Reineke Fuchs have been particularly important for the interpretation of the work : the problem of the respective originals and the question of the author.

As early as 1752, Gottsched had shown the essential traces of the versions available to him in the tradition of manuscripts and prints in the foreword to his prose edition Reineke der Fuchs . In 1834 Jacob Grimm published an edition by Heinrichs Reinhart Fuchs together with other Middle High German and Latin animal stories, including the fragment of a Reynaert II manuscript in The Hague , which was written by the Dutchman H. van Wijn (1740–1831), a Reich archivist, in Discovered in a back cover in 1780. Grimm suspected Hinrek van Alckmer, mentioned in Reynke de Vos , to be the editor of the Dutch model.

His view was supported by a discovery made by Friedrich Georg Hermann Culemann (1811–1886), Senator for Schools in Hanover, a collector of bibliophile treasures and the mediator of the Gospel Henry the Lion from Prague to the Guelph George V of Hanover in 1861. Culemann had acquired seven sheets of a print containing a Central Dutch version of the Reynaert ; you are in Cambridge today . The fragments could be identified with the printer of the Antwerp prose version, Geeraert Leeu, and formed the missing link to the Lübeck incunable of 1498; In 1862 August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben had the previously almost unknown Culemann fragments reprinted. In the more recent research of the 1980s, however, doubts arose as to the identity of the fragments with the work of Hinrek von Alkmer, as described in the Lübeck Reynke- Druck.

Research into the relationship between Lübeck's Reynke de Vos and the Dutch models was initially determined by the progress in knowledge of the text. As early as 1783, Ludwig Suhl , Lübeck's city librarian and sub-rector of the local grammar school , published the Delft prose cunabula from 1485, which was probably available to Goethe when he was working on his Reineke Fuchs alongside Gottsched's prose version . In 1852 Hoffmann von Fallersleben gave the Reineke Vos. After the Lübeck edition of 1498 in Breslau. A first summary of the state of knowledge was made in 1880.

In the 20th century, sociological questions and the history of effects became important both for the question of the author and for researching the originals; In the meantime, both aspects are seen as fundamental for philological topics, such as the place explanation , the naming of the characters or the iconography and the legal-historical problems in the story of Reineke . A bibliography of the Reineke prints up to 1800 has been available since 1992 , provided by Hubertus Menke . On the basis of the original history, since the 1990s, especially by Klaus Düwel , the history of its European reception has been increasingly researched on the basis of the traditional lines of the material.

expenditure

- Johann Heinrich Ramberg (draftsman), Dietrich Wilhelm Soltau (author), Waltraud Maierhofer (ed.): "Reineke Fuchs - Reynard the Fox. / 31 original drawings and newly colored etchings with excerpts from the German translation of the epic in the popular style v. Soltau | 31 original drawings and newly colored etchings with excerpts from the English translation of the burlesque poem by Soltau. VDG Weimar, Weimar 2016. ISBN 978-3-89739-854-2 .

- Reynaerts historie, Reineke Fuchs . Edited by R. Schlusemann and P. Wackers. (Edition Middle Dutch / High German) Münster 2005, ISBN 3-89688-256-2 .

- The Cambridge Reinaert Fragments . Edited by Karl Breul. Cambridge University Press 2010 (reprint of 1927 first edition). With facsimiles of the fragments and transcription ( online )

- Reynke de vos , Lübeck 1498. Facsimile, Hamburg 1976 ( Herzog August Bibliothek , Wolfenbüttel; microfiche signature: A: 32.14 Poet.)

- Reynke de Vos . Edited by Hartmut Kokott. Munich 1981, ISBN 3-7705-1944-2 .

- From Reinicken Fuchs . Heidelberg, 1981 (facsimile of the Frankfurt 1544 edition; with an introduction by Hubertus Menke)

- Reineke the fox . Johann Christoph Gottsched, Selected Works . Edited by Joachim and Brigitte Birke in 12 volumes (1965–1995; reprint 2005). Volume 4; Berlin / New York 1968, ISBN 3-11-018695-0 .

- Reineke Fuchs . Goethe's Works , Volume II: Poems and Epics II. Munich 1981 (based on the Hamburg edition from 1949–1967), ISBN 3-406-08482-6 .

- Reineke Fuchs . From DW Soltau. Berlin 1803. ( Google Books )

- Reineke Fuchs. Drawn in 30 sheets and etched by Johann Heinrich Ramberg . Hanover 1826.

- Reineke the fox. Edited for the educated youth . 2nd edition, embellished with 12 new coppers. Leipzig undated [1838].

literature

- Amand Berteloot , Loek Geeraedts (Ed.): Reynke de Vos - Lübeck 1498. On the history and reception of a German-Dutch bestseller. Lit, Münster 1998, ISBN 3-8258-3891-9 . (Netherlands Studies, Smaller Fonts 5)

- Klaus Düwel : Heinrich, author of "Reinhart Fuchs". In: The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . (VL) Vol. 3. Berlin / New York 1981; Col. 666-677.

- Klaus Düwel: Reineke Fuchs. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Vol. 11. Berlin / New York 2004, Col. 488-502.

- Klaus Düwel: Animal spades. In: Reallexikon der Deutschen Literaturwissenschaft . Vol. 3. Berlin / New York 2003, pp. 639-641.

- Elisabeth Frenzel : Reineke Fuchs. In: Ders .: Substances of world literature. A lexicon of longitudinal sections of the history of poetry (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 300). 2nd, revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1963, DNB 451357418 , pp. 536-538.

- Jan Goossens , Timothy Sodmann (ed.): Reynaert Reynard Reynke. Studies of a medieval animal pose. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Vienna 1980. ( PDF ) (Low German studies. Series of publications of the Commission for Dialect and Name Research of the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe. Volume 27)

- Jan Goossens: Reynke de Vos. In: The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . (VL) Vol. 8. Berlin / New York, 1992, Col. 12-20.

- Jan Goossens: Reynke, Reynaert and the European animal pos. Collected Essays. Münster / New York / Munich / Berlin 1998. (Netherlands - Studies Volume 20)

- Hans Robert Jauß : Investigations on medieval animal poetry . Tübingen 1959.

- Fritz Peter Knapp : Renart. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . (LMA) Vol. 7. Munich 1995, Col. 720-724.

- Harald Maihold : “Did I deserve a punishment because they acted foolishly?” - Legal aspects in Goethe's “Reineke Fuchs”. In: ius.full - Forum for Legal Education. 2007, pp. 105-113.

- Jill Mann : Nivardus of Ghent. In: The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . (VL) Vol. 6. Berlin / New York, 1987, Col. 1170-1178

- Hubertus Menke : Bibliotheca Reinardiana. Part I: The European Reineke-Fuchs prints up to 1800 . Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7762-0341-2 .

- Hubertus Menke , Ulrich Weber (ed.): The unholy world Bible: the Lübeck Reynke de Vos (1498-1998). Exhibition by the department for Low German language and literature at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel in cooperation with the library of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck and the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel. Dept. for Niederdt. Language and literature at Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel 1998.

- Walter Scherf : Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Reineke Fuchs . Reprint of the Stuttgart 1867 edition, with illustrations by Wilhelm von Kaulbach. Dortmund 1978, pp. 259-277. (Epilogue)

- Erich Trunz : Reineke Fuchs. In: Goethe's works. (GW) Volume II: Poems and Epics . Munich 2005, pp. 717-733. (Afterword and Notes)

- Beatrix Zumbält : The European illustrations of "Reineke Fuchs" up to the 16th century. Scientific publications of the University of Münster; Series X, Vol. 8. Two volumes (text and catalog volume). Münster 2011 (both volumes available as PDF )

Web links

Reineke Fuchs in library catalogs

- Search for Reineke Fuchs in the German Digital Library

- Search for Reinecke Fuchs in the joint union catalog

- Search for Reineke Fuchs in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Text output and scans

- Ecbasis captivi - text edition of the Bibliotheca Augustana

- Le Roman de Renart (text based on Mss. C and M) .

- Reinhart Fuchs - Manuscript of Heidelberg University Library: Cod. Pal. germ 341 (digitized version); fol. 167v - 181v

- Reynaert I - Text edition of the Institut voor Nederlandse Lexikologie (ed .: J. Jannsens, R. van Daele, V. Uyttersprot)

- Reynaert II ( Reinaerts Historie ) - text edition of the Institut voor Nederlandse Lexikologie (ed .: W. Gs. Hellinga)

- William Caxton: The History of Reynard the Fox (1481); pdf - engl. late medieval version of the Reineke material, based on the edition by Henry Morley 1889 (392 kB)

- Reynke de Vos ( memento of April 25, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) - Karl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg : Transcription of the Lübeck edition of 1498 with its woodcuts, on the pages there are links to black and white scans of the incunabulum; in the appendix ( memento of 7 July 2009 in the Internet Archive ): From the "younger glossary" on "Reinke the fox" (based on the Rostock print from 1539)

- Johann Christoph Gottsched. Reineke der Fuchs (1752) - Reprint without glosses in source writings for new German literature , ed. by Alex Bieling, 1886 (from p. 8); Scan at: austrian literature online (alo)

- Reineke Fuchs from JW von Goethe, 1793/94

- Reineke Vos. According to the Lübeck edition of 1498 - ed. by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben , Breslau 1852 (digitized version of the Braunschweig digital library )

- The Dutch folk book Reynaert de Vos, based on the Antwerp edition of 1564 - ed. by Ernst Martin , Paderborn 1876 (digitized from Cornell University Library)

Bibliography:

- Selected bibliography of animal poses , focus on Reineke precursors (University of Trier)

More on the topic:

- The fox in medieval bestiaries - with medieval ideas about the fox, symbolic content / allegorical meaning, selection of illustrations, bibliography and bestiary manuscripts

- Animals in Medieval Illuminations (French) - Website of a bestiary exhibition of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF); including a link to the Roman de Renart : Introduction (audio version, French) to the work and scans of some pages

- The illustrations of Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1846)

- Reineke Fuchs Museum

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the table of contents in details see Reynke de vos .

- ↑ Cf. also: Hans Robert Jauß: Investigations on medieval animal poetry . Tübingen 1959; Peter Schneider: The unholy realm of Reineke Fuchs . Frankfurt am Main 1990

- ↑ Düwel: Reineke Fuchs. In: EM Vol. 11 (2004), Col. 488f.

- ↑ Ecbasis cuiusdam captivi per tropologiam . The Escape of a Prisoner (Tropological). Text and translation. Edited with an introduction and explanations by Winfried Trillitzsch, historically explained by Siegfried Hoyer. Leipzig 1964. You can find brief information about the work here .

- ↑ On the website of a bestiary exhibition of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) on animals in medieval illuminations , an introduction (audio version, French) to the work and scans of some pages of a manuscript of the BNF can be found under the link roman de Renart . The text can also be found on the Internet.

- ↑ Knapp: Renart. In: LMA Vol. 7 (1995) Col. 721-722

- ↑ Mühlethaler, Jean-Claude: Satire et bestiaire - Figurativité animale et récriture dans Renart le Bestourné de Rutebeuf. In: Febel, Gisela & Maag, Georg (ed.): Bestiaries in the field of tension between the Middle Ages and the modern; Gunter Narr Verlag, 1997.

- ↑ Knapp: Renart. In: LMA , 7, 721 (1995)

- ↑ Online are text excerpts from the Reinhart Fuchs of Alsatian Heinrich available.

- ↑ Düwel: Heinrich, author of "Reinhart Fuchs". In: VL Vol. 3 (1981), Sp. 671, 675

- ↑ Knapp: Renart. In: LMA Vol. 7 (1995), col. 723; Amand Berteloot: "Were al dat laken pergement / dat dar worth ghemaket tho Gent, / men scholdet dar nicht in konen schryuen ...". To the prehistory of the "Reynke de Vos". In: Amand Berteloot et al. (1998) pp. 11–44; P. 23.

- ↑ Transcriptions of the texts edited by Jauss (Reynaert I) and edited by Hellinga (Reynaert II )

- ↑ The fox monument in Hulst (detail)

- ^ William Caxton: The History of Reynard the Fox (1481) after the edition by Henry Morley 1889

- ↑ Düwel: Reineke Fuchs. In: EM Vol. 11 (2004), Col. 492

- ↑ Goosens: Reynke de Vos. In: VL Vol. 8 (1992), Col. 17

- ↑ The library also holds a facsimile of the incunable Reynke de vos , Lübeck 1498 (Hamburg 1976) under the shelf mark: H 2 ° 278.120; a digitized version does not yet exist.

- ↑ W. Günther Rohr: To the reception of Reynke de Vos. In: Berteloot et al. (1998) pp. 103-125; here pp. 104–107.

- ↑ According to Düwel, EM Vol. 11 (2004), Col. 492

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 107, p. 115.

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 122f.

- ↑ Goosens: Reynke de Vos. In: VL Vol. 8 (1992), Col. 18

- ↑ The prints since 1498 are recorded in the bibliography by Hubertus Menke: Bibliotheca Reinardiana. Part I: The European Reineke-Fuchs prints up to 1800. Stuttgart 1992

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 104.

- ↑ See also the illustrations in Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 107, p. 115.

- ↑ Goosens: Reynke de Vos. In: VL Vol. 8 (1992), Col. 16f .; more detailed in Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 108ff.

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 112.

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), pp. 118-122.

- ↑ Alex Bieling: The Reineke-Fuchs-Gloss in their origin and development. Berlin 1884; P. 10f.

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 113.

- ^ After: Jakob Franck: Hackmann, Friedrich August . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1879, p. 297 f.

- ^ Heinrichs von Alkmar Reineke the fox with beautiful coppers; Translated into High German after the edition of 1498, and with a treatise, provided by the author, the true age and great value of this poem , by Johann Christoph Gottscheden. Leipzig and Amsterdam, published by Peter Schenk, 1752. Introduction by the editor , Section V, pp. 47 and 48

- ↑ Erich Trunz: Reineke Fuchs. GW, Afterword Vol. 5; P. 718.

- ↑ See letter to his sister Cornelia of October 13, 1765

- ↑ Erich Trunz (GW) Vol. 5, pp. 717-719.

- ↑ Erich Trunz (GW) Vol. 5, p. 726.

- ↑ Quoted from Walter Scherf: Wilhelm Kaulbach and his Reineke-Fuchs illustrations. In: Reineke Fuchs (1978), p. 256.

- ↑ Erich Trunz (GW) Vol. 5, p. 723.

- ^ Walter Scherf in: Reineke Fuchs (1978), p. 263f.

- ↑ Walter Scherf in: Reineke Fuchs. (1978), p. 265.

- ^ Rohr in Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 125.

- ^ Rohr in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 124.

- ^ A fragment from Reineke Fuchs' last song . B (erlin) 1871

- ↑ See also Dr. Faust: Esterhazy. Reineke Fuchs freely to Göthe. Brussels 1898, a satire on the Dreyfus affair .

- ↑ Other Volksbuch editions by Joseph Görres , Gustav Schwab (1817), GO Marbach (1840) and others

- ↑ Weblink ( Weber's book illustrations ); Page with a fox picture ( memento from October 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Hegenbarth: Drawings for Goethe's verse-epic 1923; Published in: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Reineke Fuchs . Island: Frankfurt am Main 1964; Anniversary edition 1999 (out of print)

- ^ Friedrich Rassmann: Reineke Fuchs. Liter. Commission Comtoir: Ronneburg 1820

- ↑ For example: Reineke the fox - a legend from the animal kingdom. Transferred by Severin Rüttgers from the Low German edition of 1498 . Cologne: Hermann & Friedrich Schaffstein, undated (with a foreword for younger readers) The text appeared in large Fraktur, the Art Nouveau cover refers to an appearance around 1900. Also published in Gothic script was: Reineke Fuchs (Free Nachdichtung des Niederdeutschen Reinke de Vos.) By Fedor Flinzer , Julius Lohmeyer and Edwin Bormann . Glogau: Carl Flemming 1881.

- ↑ found again 1991/2005; Egbert Barten and Gerard Groeneveld: Reynard the Fox and the Jew Animal (1996)

- ^ Franz Fühmann (Works), Volume 5. Hinstorff Verlag: Rostock 1993 (new edition of the work edition 1977–1988); P. 317ff.

- ↑ Reinardus Vulpes . Emendavit et adnotavit Guilelmus Knorr. Utini, impensis Petri Voelckersii, MDCCCLX (sic)

- ↑ See for example: Bender German reading book , around 1960: How Reineke was sued and convicted and still got away from the gallows. Told from the folk book by Herbert Kranz . (Pp. 163–179)

- ↑ See German lessons. Reader 7 . Berlin 1992; P. 151 (with an explanation of Reineke's precarious situation and the request to bring the wolf into play in order to save him, along with an illustration that suggests Reineke's malicious solution)

- ↑ Goosens: Reynke de Vos. In: VL Vol. 8 (1992), Col. 12-20

- ^ Goossens: Reynke de Vos. In: VL Vol. 8 (1992), Col. 17

- ↑ Thorsten Heese: "... an own local for art and antiquity" - the institutionalization of collecting using the example of Osnabrück museum history. Dissertation Halle – Wittenberg 2002; P. 382. (PDF; 2.2 MB)

- ^ Cambridge, University Library, Inc. 4 F 6.2 (3367)

- ^ C. Schiefler: The German late medieval "Reineke-Fuchs" poetry and its adaptations up to modern times. In: Aspects of the Medieval Animal Epic . Mediaevalia Lovaniensia Series I / Studias III, Leuven 1975; P. 87.

- ↑ Jan Goossens (Ed.): Reynaerts Historie - Reynke de Vos. Comparison of a selection from the Dutch versions and the Low German text from 1498. Darmstadt 1983; S. XLIIff. After: Amand Berteloot in: Berteloot et al. (1998), p. 15.

- ↑ The historie vā reynaert de vos. After the Delft edition of 1485 . Promoted for exact printing by Ludwig Suhl, city librarian and subrector at the grammar school. in Lübeck. Lübeck and Leipzig, 1783 ( digitized version )

- ^ Friedrich Prien: On the prehistory of Reinke Vos. Niemeyer: Halle 1880. Special print from: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature . 8: 1-53 (1982).

- ↑ Jan Goossens: The author of the "Reynke de Vos". A poet profile. In: Berteloot et al. (1998), pp. 45-79; Hubertus Menke: Lübeck's literary subculture around 1500. In: Berteloot et al. (1998), pp. 81-101.