Emblem (art form)

An art form is called an emblem , the origin of which goes back to the humanists of the Renaissance . In these works, mostly published in book form, images and texts were linked to one another in a special way. The three parts of an emblem related to each other and made it possible to recognize the hidden meaning behind the often puzzling first impression. The noun emblema ( Greek ἔμβλημα ) was used in Latin and ancient Greek for different parts, i.e. H. Mosaics and inlays , metal decorations, but later in a figurative sense also for borrowed and inserted image or text elements. Emblems conveyed behavioral norms and wisdom in an attractive, graphic and literary form. Their widespread use has had an impact on many areas of European culture. The 16th and 17th centuries are considered to be the heyday of the emblems.

The art historical meaning of the terms emblem and emblematic described here does not exactly correspond to the current colloquial use of the term. The current Duden defines emblem as “mark, national emblem ; Symbol "and emblematic as" symbolic representation; Emblem research ". Today's scientific discipline of emblematics deals not only with emblems, but also with related but independent forms such as imprese and titulus , which differ from the originally three-part emblems both formally and in terms of their origin and development.

Historical overview

Influences

The classical emblems of the Renaissance had a variety of sources in older literature and iconography . Through an anthology published in Florence in 1494 ( Anthologia epigrammatum Graecorum ) the knowledge of the Greek epigrammatists had been considerably expanded and disseminated. Other influences came from medieval religious literature, from the knightly - courtly symbolism of France and Burgundy and the imprints developed from them in Italy around 1500 as well as from didactic literature with a natural history background, e.g. B. the Physiologus , a script with early Christian animal symbolism. The work was probably made in Alexandria in the 2nd century . In Latin translation and in various national languages, it was widespread in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. From descriptions of animals, occasionally also of trees or stones, religious doctrines or moral rules of behavior were derived through allegorical interpretation.

One of the important influences on the further development of the emblems was the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna , a novel-like text with a highly complex, often puzzling quality, linguistically and in terms of content. After the first edition in Venice in 1499, the work, illustrated with 172 woodcuts, initially received little attention, only to find widespread use throughout Europe after the new edition in 1545. The formation of a special Renaissance hieroglyphics was also significant. The enigmatic characters of ancient Egypt had been mentioned by writers of antiquity and were seen on Egyptian antiquities in Italy. In 1422 the Greek version of Horapollon's Hieroglyphica was brought to Florence, and a Latin translation was printed in 1517. The work, presumably written in the Hellenistic period, contained a methodologically inadequate attempt to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs . It provided a kind of cipher, a dictionary of images with interpretation, in which a certain magical-symbolic background was assumed for each character, although many of them were simple phonetic characters. The European humanists adopted these interpretations; numerous motifs from this fund were included in the emblem books.

The beginnings

The origin of the first emblems can be dated with unusual accuracy. The first book of this new genre was produced in 1531 in Heinrich Steyner's printing house in Augsburg ; it was the Emblematum liber , a narrow volume with texts by the Milanese lawyer and humanist Andrea Alciato . Alciato had already translated the epigrams of the Anthologia into Latin years earlier and had them printed in 1529. Each epigram was given a short heading, the doctrinal essence of the poetic text. A well-known scholar, the German humanist Konrad Peutinger (1465–1547) initiated the Augsburg edition, for which Alciato's texts were used. The woodcuts for the book, probably made by Hans Schäufelin (his monogram can be found in a second Augsburg edition from 1531), were based on illustrations by the Augsburg artist Jörg Breu the Elder . Andrea Alciato was apparently not directly involved in the creation of the first edition. In the Paris version of 1534 authorized by him, he was very critical of the earlier edition, which had various technical and editorial errors.

The newly developed historical form of the emblem thus consisted of three parts: heading, image and poetic text or lemma , icon and epigram . In principle, this three-way division was considered binding for a long time, even if not always in the original, strict version; the characteristics of the three elements were occasionally varied.

- Examples from Andrea Alciato's Emblematum liber , Augsburg 1531:

Further development

Alciatos Emblematum liber became the model for all emblems and was distributed in around 125 editions in large parts of Europe by 1781. Important early new editions appeared, for example, in Paris in 1534 (illustrated with woodcuts based on drawings by a German Holbein student) and in Frankfurt am Main in 1566 (with woodcuts by Jost Amman and Virgil Solis ). The first German translation by Wolfgang Hunger was published in Paris in 1542: Das Buechle der verschroten Werck .

The book Alciatos initially contained 104 emblems, it was expanded several times in new editions and soon after the first edition was copied by other authors. Unauthorized reprints as well as adaptations and new compilations of older models were characteristic of the production of emblem books. Absolute originality was not a relevant criterion. Rather, the aim was to deal intensively and creatively with the traditional text and image material recognized as valuable. The structure of the books changed over time. Alciato had initially dealt with topics from various areas of human life, without specifically classifying them. In the more extensive later books, the contents were grouped according to subject areas; since the end of the 16th century, entire emblem books on individual thematic categories have appeared.

The original emblematic form with its balanced relationship between text and image was gradually lost in the 17th century. Since the early 17th century, the image had a clear predominance over the text. The development of the emblems ended in the 18th century; after just a few decades they were of no importance. Up until the 19th century, traces could only be found in allegorizing genre painting and pictorial poems or in special forms such as the symbolism of Masonic lodges .

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), who, as the new discoverer of classical antiquity, recommended the “noble simplicity” of Greek works of art as an ideal for imitation, decidedly rejected emblems as an art form. In 1756 he described "a time in the world when a large crowd of scholars, as it were, revolted with a veritable rage to eradicate good taste". Real nature and its direct artistic representation were felt to be inadequate and were deemed to be obliged to “make it funnier”. The symbols created in this way, which needed an explanatory text for understanding, are "of low rank in their nature". The poet and philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) gave a more differentiated judgment. He, too, was of the opinion that one must distinguish “the spirit of pure Greek allegory from the emblematic shadow of later times”. At the same time he found “the emblematic poetry of the Germans” very remarkable. “Whether it be ground window panes, woodcuts or copperplate engravings ; people interpreted them and liked to invent something that could be interpreted. This helped German art. […] I wanted us to have a history of these German pictorial sayings with their strangest products. "

The scientific rediscovery of the emblem only began in the 20th century. Emblems have become the subject of intensive interdisciplinary research, for which extensive material is now available again: in addition to the rare originals, numerous reprints, manuals and special databases. An international association, the Society for Emblem Studies , supports the scientific endeavors.

In his standard work on emblem research from 1947, the art historian Mario Praz named, in addition to a large number of anonymously published emblem books, over 600 authors known by name, many of them with several books and repeated editions. A seven-digit number is assumed for the total circulation of all emblematic works on the European book market from the 16th to the 18th century. About a third of all emblem books were created in Germany. However, those involved - authors, draftsmen, wood cutters or engravers and printers - often belonged to different nations. The use of the language - initially mainly the supranational scholarly language Latin, later often several languages simultaneously in one edition - contributed to making the emblem literature a transnational European phenomenon despite certain national peculiarities.

Individual aspects

Categories

The thematic variety of the emblems can be assigned to the following categories:

- general ethical - moral emblematics;

- worldly love emblematic;

- political emblems ( prince mirror , emblematic congratulatory writings, funeral emblems, ie emblems associated with burials, etc.);

- religious emblematics (collections of sermons, Marian and saints emblematics, religious love and heart emblematics, emblematized rules and stories of orders , edification literature, emblematic dance of death).

The three-part form

The lemma (Greek λῆμμα, Latin vocalium signum or inscriptio , Italian motto ) was a short Latin, rarely also a Greek formulation, which contained an ethical requirement, a rule of life or a motto. It shouldn't be more than five words; occasionally a single word was enough to indicate the essence of the emblem.

The icon (Greek εἰκών, Latin pictura ) is the pictorial part of the emblem, for which there were no narrow boundaries in terms of content or form. In Alciato's first edition from 1531, woodcuts in different formats were incorporated into the text flow without any special page design. Even in the slightly later editions, such as the edition in Paris in 1534, the image formats had become almost uniform. Together with the lemma and epigram, they each took up a book page in a closed typographic design, so that the unity of the three-part form of the emblem became clear. At the same time, the artistic level of the Icones approached the literary quality of the texts. Scholars and poets dealt with a theory of emblematics, and a specific, sometimes violently polemical literature emerged. Theorists of the emblematic tried to direct the development of the icons in certain directions. For example, they demanded that the full human figure should not be depicted; individual body parts, however, should be allowed. The academic discussions on which such demands were based remained largely ineffective in the rapidly progressing, practical development of the emblem.

The epigram (Greek ἐπίγραμμα, also Latin subscriptio ) as the third component of an emblem had the task of explaining the often puzzling combination of lemma and icon or at least facilitating the solution of the puzzle. This role, which was initially only a commentary and was subordinate to the first two parts, was enhanced by the use of the classical languages Greek and Latin in forms of ancient poetry . In addition, the solution tips for the puzzles were still artfully disguised. The epigram was named after an ancient literary genre without its characteristics being adopted in all points in the emblematic. The agreement consisted in the use of certain forms of language used in antiquity, as well as in the intention to poetically interpret an object, a concept or the quality of a person. If the interpretation of the lemma and icon required greater efforts, an epigram could take on the character of an extensive commentary and thus break the original balance of the emblem. In the course of the historical development, the artfully coded form of interpretation has become increasingly simpler, easier to understand. The poetic form was often dispensed with, and the various national languages were used instead of ancient Greek or Latin.

The riddle character

In the 16th century in particular, the emblem's enigmatic character was in the foreground. It was aimed at humanistically trained people who were able to recognize those fragments from ancient texts that were used for lemma and epigram; Only they could find and evaluate the original motifs in the Icones, as they were handed down in ancient medals, gems , sculptures , etc. As long as the occupation with the emblem remained a pastime for the few educated and at the same time a proof of humanistic education, selected difficult combinations were relatively frequent. This changed since the 17th century, when emblems were increasingly supposed to disseminate educational and moral content - for example, as illustrations of well-known proverbs - so the resolution could not be so difficult that the didactic purpose was missed.

Duke Heinrich Julius zu Braunschweig and Lüneburg , Prince of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1589–1613) showed a particular preference for emblematic representations with a series of thalers. For example, in the coin image of the truth thaler, the personified naked truth can be seen, which stands with its feet on the symbolized slander and lies. The inscription in the field confirms this: VERITAS / VIN - CIT / OM - NIA / CALVMNIA / MENDACIUM (Latin = The truth conquers all slander and lies).

The personified truth on the taler was mistakenly viewed as Christ. The thaler served the duke as a means of propaganda in disputes with some noble families in his country.

Four characteristic examples

- Lemma: Foedera (“Covenants”; source: Emblematum libellus , Paris 1534). Icon: A lute is on a table. The explanation of the apparently incoherent content of the heading and the subject of the picture is given by the twelve-line Latin epigram. The lute is dedicated to a duke , presumably Massimiliano Sforza (1493–1530): “[…] may our gift please you at this time when you are planning to enter into new treaties with allies. It is difficult, if not for a learned man, to tune so many strings, and if one string is not stretched well or breaks (which is easy to do), all grace of the instrument is gone and fine singing will be spoiled. So when the Italian princes unite in an alliance, there is nothing to fear. […] But if someone becomes apostate (as we often see), then all harmony dissolves into nothing. ”For learned contemporaries, the at first glance senseless combination of lemma and icon was not an insoluble problem even without explanation. Cicero had used a similar comparison in De re publica , and Augustine cited this passage in one of his writings. The lyre as a symbol of unity was a literary metaphor used several times in the ancient scriptures .

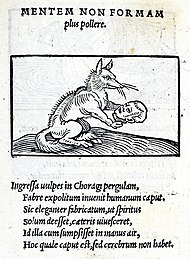

- Lemma: Mentem non formam plus pollere (“ Cleverness counts, not external beauty”; source: Emblematum liber , Augsburg 1531). Icon: A fox seems to be looking at a person's head. The epigram is taken from the fables of Aesop and says in free prose translation: “A fox found the mask of an actor in the fundus of a theater, perfectly formed, so perfect that only the spirit was missing, in everything else it seemed alive. The fox picked her up and spoke to her: What a head - but without a brain! "

The source for the following two emblems, two colored re-engravings after Daniel Heinsius ' Emblemata amatoria , is the anthology Théâtre d'Amour from 1620. The lemma and epigram are combined as a transcription with the icon and have been supplemented by six-line French poems by an unknown author.

- Lemma: Omnia vincit amor (“ Cupid conquers everything”), from a pastoral poem by Virgil . Icon: Cupid rides a reluctant lion. The Latin epigram after Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) translates as follows: "I have seen him who can tame the wild lion: I have seen him who is the only one who can tame hearts: Cupid." This emblem is one of the am most frequently varied symbols of the emblematic. Alciato had already used the basic motif in 1531 under the lemma Potentissimus affectus amor ("Love is the strongest passion").

- Lemma: Ni mesme la mort ("Not even death"). Icon: Cupid looks at a vine that twines around a withered tree. The Latin epigram in German: "Neither the death of the plane tree does away with the vine, nor does the last day, which destroys everything else, take away our love."

Emblematic literature in the Netherlands

Emblems were particularly popular in the Netherlands. In Antwerp (today located in the Flemish part of Belgium), Christoph Plantin's book printing house was an important center of emblem literature, a large company with up to 16 printing presses and 80 employees. In the northern provinces in particular, numerous emblem books appeared in the 17th century, which, against the background of the theological movement of Calvinism that predominated there, mainly addressed ethical, moralizing claims. These emblems were mostly more direct in the statements and more realistic in the representations than the Italian examples. The main representatives of Dutch emblem literature were Jacob Cats (1577-1660) and Daniel Heinsius (1580-1655). Cats, the best-known Dutch author of the 17th century, was also the author of several widespread emblem books such as Sinn'-en-Minne-beelden ("Meaning and Love Images") and Spiegel van den Ouden ein Nieuwen Tijdt ("Spiegel der alten und der new time ”), both with illustrations by Adriaen van de Venne . In literarily undemanding verses, he conveyed simple, universally valid truths. With beelden Sinn'-en-Minne- he delivered a special feature for each emblem two alternative solutions: the spiritual variant directed to the intellect ( mind ), the secular referred to the love ( minne ). Cats used the same symbols several times in books with different titles, this also applies to Monita Amoris Virginei , Amsterdam 1620 (see fig. At the head of the article); a German translation of this text was published in Augsburg in 1723 under the title Newly opened school in front of the still single woman, which in it is best taught by the highly learned Doctor Jacob Cats through 45 invented meaning pictures ...

The humanist scholar Daniel Heinsius , born in Ghent and since 1603 has been a professor and librarian in Leiden , was the author of an emblem book that was first published in 1601 under the title Quaeris quid sit amor (“You want to know what love is?”) was the first emblem book devoted exclusively to the topic of worldly love. In later editions it was given the title Emblemata amatoria , which became the generic name of this topic. Heinsius had written Dutch verses under a pseudonym ( Theocritus a Ganda - Daniel von Gent) to engravings by Jakob de Gheyn II . The poems were taken over unchanged in 1616 in Heinsius' collection Nederduytsche Poema ("Dutch poems"). Another, private compilation of emblems, dated 1620 ( Théâtre d'Amour ), contains the subsequently colored copper engravings from 1601, but the verses are replaced by independent French poems by an anonymous author.

Encyclopedias

Since the second half of the 17th century, not only the usual emblem books, but also extensive encyclopedias with emblematic material appeared. They contained motifs from various emblem books of the 16th and 17th centuries, plus very short, often multilingual explanations, but no literary parts. The practical application of this material in arts and crafts has been proven many times. Important examples of this kind were:

- Il mondo simbolico by the Italian clergyman Filippo Picinelli, 1000 pages long, published in Italian in Milan in 1653, translated by the Augustinian monk Augustin Erath and expanded into the Mundus symbolicus (published 1687–1694).

- Symbolographia sive De Arte Symbolica sermones septem by Jacobus Boschius, published in 1701 by Caspar Beucard in Augsburg and Dillingen . It contained 3347 images.

- Emblematic Emotional Pleasure When contemplating 715 the most curious and delightful symbols with their relevant German-Latin-French and Italian inscribed . This somewhat smaller anthology was published in Augsburg in 1699 as a sample book for visual artists and artisans. The work was the abridged translation of a collection first published in 1691 by Daniel de La Feuille in Amsterdam, which in turn is based on a multi-part compilation by the French engraver Nicolas Verrien.

Examples from the encyclopedia Emblematic Minds Pleasure […] , Augsburg 1699:

Applications

Already Alciato saw in his work a sample book for artisans, which was suitable to help with the ingenious design of living and representation rooms of the ruling and wealthy. In a Lyon edition of his Emblemata , he described various possible uses and concluded by emphasizing “that the face of things that look to the common benefit is eloquent everywhere and is beautiful to look at. So whoever wants to decorate his own with the acuteness of a brief saying and a festive picture: He will have an abundance of the treasure in this little book ”. This gave the emblems a direct benefit. Emblematic representations were used for glass windows, fabrics, wallpaper, furniture, tiled stoves and the like, but also to decorate drinking vessels, bells, swords or cannons, as well as for festival and stage decorations, for wall and ceiling paintings - z. B. also in churches and monasteries - and for decorative stucco work . Emblems played an important role in the design of coins and medals . They gave many suggestions for the book industry, the popular motifs appeared on title pages and dedications, in printer's and publisher's logos. A well-known example is the printer's mark of the Aldus press, founded by the Venetian publisher and printer Aldus Manutius . Alciato presented the motif - dolphin and anchor - which had been used as a printer's mark since 1502, as an exemplary application of his emblems and included it in his emblemata.

Essential pictorial motifs in works of the fine arts of that time, especially in Dutch painting, are revealed through knowledge of the emblematic. A typical example is the portrait of a couple by Frans Hals , created around 1625. The couple is depicted under a tree entwined with ivy. This frequently varied emblem motif was used as a symbol both negatively (the ivy chokes the tree that supported it) and, as here, positively (the tree supports the ivy, a metaphor for the permanence of love). The thistle on the left in the picture as a symbol of hardship and the cheerful baroque garden on the right were regarded as an indication of the persistence of love in good and bad days.

In non-literary emblematic applications such as those mentioned here, it was hardly ever possible to include an epigrammatic interpretation. The emblematic material was usually reduced to the picture, at best the motto. Often, however, the emblems used belonged to program groups that dealt with a common topic, that is, they were mutually coordinated and thus easier to explain. In addition, they were often known to viewers from other contexts.

Further examples

Some popular emblem books not yet mentioned here that were often used by artists and artisans (selection):

- Guillaume de La Perrière : Theater des bons engins , Paris 1539.

- Johannes Sambucus : Emblemata ... , Vienna 1564.

- Georgette de Montenay : Emblemes, on Devises Chrestiennes , Lyon 1571.

- Nicolaus Reusner : Emblemata Nicolai Reusneri , Frankfurt / M. 1581.

- Cesare Ripa : Iconologia , Rome 1593.

- Nicolaus Taurellus : Emblemata Physico Ethica , Nuremberg 1595.

- Otto van Veen : Amorum Emblemata , Antwerp 1608.

- Gabriel Rollehagen : Nucleus emblematum, Hildesheim 1611.

- Daniel Heinsius : Het Ambacht van Cupido , Leyden 1615.

- Julius Wilhelm Zincgref : Emblemata . Frankfurt / M. 1619.

- Jacob Cats : Proteus ofte Minne-beelden , Rotterdam 1627.

- Daniel Cramer : Emblemata moralia nova , Frankfurt / M. 1630.

literature

- Frank Büttner, Andrea Gottdang: Introduction to Iconography. Ways to interpret image content. Second, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-53579-6 , p. 137 ff.

- Emblematic. In: Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauss (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Kunst. Volume 2: Cin - Gree. Revision. EA Seemann, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-363-00045-6 , p. 317.

- Wolfgang Harms , Gilbert Hess, Dietmar Peil, Jürgen Donien (eds.): SinnBilderWelten. Emblematic media in the early modern era. Institute for Modern German Literature, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-87707-534-7 (catalog for the exhibition on the occasion of the 5th International Emblem Congress in Munich, August 9-14, 1999).

- William S. Heckscher , Karl-August Wirth: Emblem, emblem book . In: Real Lexicon on German Art History . Volume 5: Email - Donkey Ride. Druckmüller, Stuttgart 1967, ISBN 3-406-14005-X , Sp. 85-28.

- Arthur Henkel , Albrecht Schöne (Ed.): Emblemata. Handbook on the symbolic art of the XVI. and XVII. Century. Pocket outlet Metzler, Stuttgart et al. 1996, ISBN 3-476-01502-5 .

- Ingrid Höpel, Ulrich Kuder (ed.): Emblem books from the Wolfgang J. Müller collection in the Kiel University Library. Catalog (= Mundus Symbolicus. 1). Ludwig, Kiel 2004, ISBN 3-933598-96-6 .

- John Landwehr: Emblem and Fable Books Printed in the Low Countries. 1542-1813. A Bibliography. Third, revised and expanded edition. Hes & De Graaf, Utrecht 1988, ISBN 90-6194-177-6 .

- Walter Magass: Hermeneutics and Semiotics. Scripture - Sermon - Emblematics (= Forum Theologiae Linguisticae. 15). Linguistica Biblica, Bonn 1983, ISBN 3-87797-025-7 .

- Mario Praz : Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery. Volume 2: A Bibliography of Emblem Books. Warburg Institute, London 1947.

- Albrecht Schöne: Emblematics and Drama in the Baroque Age. Third edition with annotations. CH Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-37113-2 .

- Théâtre d'Amour. (The garden of love and its joys. The rediscovery of a lost book from the Baroque period). Complete reprint of the colored “Emblemata amatoria” from 1620. Essay and texts by Carsten-Peter Warncke. Taschen, Cologne u. a. m. 2004, ISBN 3-8228-3126-3 .

- Antje Theise, Anja Wolkenhauer (eds.): Emblemata Hamburgensia. Emblem books and applied emblematics in early modern Hamburg (= publications of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky. Vol. 2). Ludwig, Kiel 2009, ISBN 978-3-937719-92-4 .

- Carsten-Peter Warncke: Speaking Pictures - Visible Words. The understanding of images in the early modern era (= Wolfenbütteler Forschungen. Vol. 33). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02725-8 (At the same time: Wuppertal, Universität, habilitation paper, 1985).

- Anja Wolkenhauer : Too difficult for Apollo. Antiquity in humanistic printer's marks of the 16th century (= Wolfenbütteler Schriften zur Geschichte des Buches. Vol. 35). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-447-04717-8 (on the interrelationship between printer characters and emblems; also: Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2000).

Web links

- The Utrecht Emblem Project - digitized emblem books

- Glasgow University Emblem website

- Liber emblematum of Andrea Alciati (Latin / English) at the Memorial University of Newfoundland

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden, the German spelling. Based on the current official spelling rules (= Der Duden. Vol. 1). 25th, completely revised and expanded edition. Dudenverlag, Mannheim et al. 2009, ISBN 978-3-411-04015-5 .

- ^ University of Glasgow, Project Alciato at Glasgow .

- ↑ Arthur Henkel, Albrecht Schöne (Ed.): Emblemata. Handbook on the symbolic art of the XVI. and XVII. Century. 1996, p. IX.

- ^ Mario Praz: Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery. Volume 2: A Bibliography of Emblem Books. 1947.

- ↑ Arthur Henkel, Albrecht Schöne (Ed.): Emblemata. Handbook on the symbolic art of the XVI. and XVII. Century. 1996, p. XVII.

- ↑ Emblematics. In: Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauss (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Kunst. Volume 2. Revised. 1989, p. 317.

- ↑ Helmut Kahnt: Das große Münzlexikon… (2005), p. 515

- ↑ Frank Büttner, Andrea Gottdang: Introduction to Iconography. Second, revised edition. 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Website of the University of Glasgow on the emblem "Mentem non formam plus pollere" by Alciato .

- ↑ Théâtre d'Amour. 2004, folio 7.

- ↑ Théâtre d'Amour. 2004, folio 26.

- ^ Inge Keil: Augustanus Opticus. Johann Wiesel (1583–1662) and 200 years of optical craftsmanship in Augsburg (= Colloquia Augustana. Vol. 12). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-05-003444-0 , p. 181 f.

- ↑ Théâtre d'Amour. 2004.

- ↑ Christina Eddiks: On the trail of the emblem. Cologne 2004, ( digitized version (PDF; 972 kB) ).

- ↑ Anja Wolkenhauer: Too difficult for Apollo. Antiquity in humanistic printer's marks of the 16th century. 2002, pp. 53-72.

- ↑ Frank Büttner, Andrea Gottdang: Introduction to Iconography. Second, revised edition. 2009, p. 140.

- ↑ Emblematics. In: Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauss (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Kunst. Volume 2. Revised. 1989, p. 317.

- ^ Theodor Verweyen , Werner Wilhelm Schnabel : Applied Emblematics and Studbook. Interpretation problems using the example of processed "Emblemata Zincgrefiana". In: Hans-Peter Ecker (Ed.): Methodically reflected interpretation. Festschrift for Hartmut Laufhütte on the occasion of his 60th birthday. Rothe, Passau 1997, ISBN 3-927575-59-3 , pp. 117-155.