encyclopedia

An encyclopedia ( ), formerly also from the French : Encyclopédie (from ancient Greek ἐγκύκλια παιδεία enkýklia paideía , German 'circle of sciences and arts, which every free Greek had to pursue in youth before he entered civil life or dedicated to a special study' , see Paideia ), is a particularly comprehensive reference work . The term encyclopedia is intended to indicate detail or a wide range of topics, such as in the case of a person who is said to have encyclopedic knowledge. A summary of all knowledge is presented. The encyclopedia is therefore an overview of the knowledge of a specific time and space, which shows connections. In addition, such works are referred to as specialist encyclopedias that only deal with a single subject or subject.

The meaning of the term encyclopedia is fluid; Encyclopedias stood between textbooks on the one hand and dictionaries on the other. The Naturalis historia from the first century AD is considered to be the oldest completely preserved encyclopedia. Above all, the great French Encyclopédie (1751-1780) enforced the term "encyclopedia" for a technical dictionary . Because of their alphabetical order, encyclopedias are often referred to as encyclopedias .

The current form of the reference work has developed primarily since the 18th century; it is a comprehensive non-fiction dictionary on all topics for a broad readership. In the 19th century, the typical neutral, factual style was added. The encyclopedias were structured more clearly and contained new texts, not mere adaptations of older (foreign) works. For a long time, one of the most well-known examples in the German-speaking world was the Brockhaus Encyclopedia (from 1808), and in English the Encyclopaedia Britannica (from 1768).

Since the 1980s, encyclopedias have also been available in digital form, on CD-ROM and on the Internet. Some are continuations of older works, some are new projects. A particular success was Microsoft Encarta , first released on CD-ROM in 1993 . Founded in 2001, Wikipedia has grown into the largest Internet encyclopedia.

expression

definitions

The ancient historian Aude Doody called the encyclopedia a genre difficult to define. Encyclopedism is the pursuit of universal knowledge or the sum total of general knowledge (of a particular culture). Specifically, the encyclopedia is a book "that gathers and organizes either the entire set of general knowledge or an exhaustive spectrum of material on a specialist subject." The encyclopedia claims to provide easy access to information about everything that individuals have about their world need to know.

For the self-understanding of encyclopedias, the forewords of the works are often evaluated. In the 18th and especially the 19th centuries, they emphasized that they summarized knowledge, not for specialists but for a wider audience. In the foreword of Brockhaus , for example, it says in 1809:

“The purpose of such a dictionary can by no means be to provide complete knowledge; rather, this work—which is meant to be a kind of key to opening one's way into educated circles and into the minds of good writers—is composed of the principal knowledge of geography, history, mythology, philosophy, natural science, the fine arts, and other sciences, contain only that knowledge which every educated person must know if he wants to take part in a good conversation or read a book [...]"

The librarian and encyclopedia expert Robert Collison wrote around 1970 for the Encyclopaedia Britannica in the introduction to the corresponding Macropaedia article:

"Today most people think of an encyclopedia as a multi-volume summary of all available knowledge, complete with maps and a detailed index, with numerous appendices such as bibliographies, illustrations, lists of abbreviations and foreign expressions, gazetteers, etc."

development into the modern term

The modern term "encyclopedia" is composed of two Greek words: ἐγκύκλιος enkýklios , going around in a circle, also: comprehensive, general, and παιδεία paideía , education or instruction. The resulting ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία referred to the "choral education", meaning originally the musical training of young freeborn Greeks in the circle of the theater choir . The Greeks did not have a binding list of the taught subjects. Modern scholars prefer to translate the Greek expression as general education, in the sense of basic education.

The Roman Quintilian (35 to approx. 96 AD) took up the Greek expression and translated it. Before boys would be trained to be orators, they should go through the education path (the orbis ille doctrinae , literally: circle of teaching). Vitruvius also called ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία a preparatory training for the specialization he aspired to become an architect. The subjects mentioned varied accordingly. For example, Quintilian mentions the areas of geometry and music for speakers.

It remains unclear what Pliny meant when he mentioned the τῆς ἐγκυκλίου παιδείας (tês enkýkliou paideías) in the preface to his Naturalis historia (ca. 77 AD). This is not only due to the vagueness of the possible subjects, but also to unclear passages in the text. The ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία eventually became a collective term for the (seven) liberal arts that developed in the Roman Empire , the artes liberales .

The word encyclopedia goes back to an incorrect back-translation of the passage in Quintilian. This tas Encyclopaedias in Pliny editions since 1497 then prevailed the expression. It has been taken as a Greek translation of orbis doctrinae . The expression then appeared in national languages in the 1530s. In the middle of the 16th century, the word could be used without further explanation in book titles for works "in which the entirety of the sciences is presented according to a specific order", according to Ulrich Dierse. The emphasis was not on totality, but on order.

Guillaume Budé used the Latin neologism in 1508 in the sense of an all-encompassing science or scholarship. The word appeared for the first time in a book title in 1527. At that time, the southern Dutch pedagogue Joachim Sterck van Ringelbergh published : Lucubrationes, vel potius absolutissima κυκλοπαίδεια , nempe liber de ratione studii (“Night work, or rather most complete κυκλοπαίδεια [ kyklopaideia]] the method of learning). It first appeared as the main title of a book in 1559: Encyclopaediae, seu orbis disciplinarum ( Encyclopaedia , or the Circle of Subjects) by the Croatian Pavao Skalić .

The English Cyclopaedia of 1728 was an alphabetical reference work, a dictionary of the arts and sciences . The breakthrough of the name encyclopedia came only with the great French Encyclopédie (1751 and following years). Based on the model of this work, the term for a general technical dictionary was established.

In addition, the word was also used for the recognition of the unity of knowledge; This is how the philosopher Christian Appel described the "Chair for General Encyclopedias" established at the University of Mainz in 1784. In education, you start with simple sensory impressions and experiences, then you come to coherent scientific wisdom via a process of abstraction. But these are scattered, so a summary is needed. So the encyclopedia should not be at the beginning of the university studies, but at the end, as the crowning glory. For research into encyclopedias, the term encyclopedia has become established.

Other designations

While for the Romans the titles of reference and textbooks were mostly sober, metaphors predominated from late antiquity to the early modern period :

- Comparisons with nature, with gardens, flowers and food were particularly common. For example, the author was a flower picker or a busy bee that collects knowledge like pollen. The works were then called Florilegia (Flower Collection), Liber Floridus (Blossoming Book) or Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Treasures).

- References to the light intended to enlighten the reader were also popular: Elucidarium , Lucidarius .

- The books were treasures: Tresor (treasure), Gemma gemmarum (jewel of jewels), treasury of mechanical arts ( Agostino Ramelli ), Margarita (pearl).

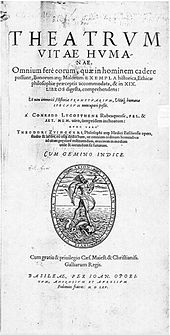

- Theatrum , setting, as in Theatrum Anatomicum referred to the representational character.

- Bibliotheca was an indication that the work was compiled from older books.

- The work was seen as a mirror of the world: speculum , imago mundi .

- Sources of water were referred to in the Livre de Sidrac, la fontaine de toutes sciences , and the allegory of urban planning in the Livre de la Cité des Dames .

- Historia was common in natural history because of Pliny and originally meant ordered knowledge. Otherwise, Historia was usually a chronological treatise into which geographic and biographical knowledge was woven.

- Ars magna (great art) is the claim of Ramon Llull and Athanasius Kircher to present an excellent performance.

Alphabetically arranged encyclopedias were called or are called dictionarium , dictionary or lexicon . Other designations are: encyclopedic dictionary , subject dictionary , real dictionary , plus real lexicon and real encyclopedia , conversation lexicon , universal lexicon, etc.

In English and French, dictionary or dictionnaire was widespread, often in the summary dictionary of the arts and sciences or dictionnaire des arts et des sciences . In German, this is reflected in the title of the General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts by Ersch-Gruber (1818–1889). The arts are usually understood to be the mechanical and manual arts, and the term science should not be interpreted too narrowly, as theology was still naturally counted as a science at that time. Real or realia stands for things as opposed to terms or words, so a real dictionary is a technical dictionary and not a language dictionary.

story

Literary genre and concept do not run parallel to each other in the history of the encyclopedia. It is therefore debatable whether encyclopedias existed at all before modern times. At least the ancient and medieval authors were not aware of such a literary genre. There is widespread agreement, for example, to regard the Naturalis historia from Ancient Rome as an encyclopedia. However, there is a risk of an anachronistic view, namely seeing an ancient work through modern eyes and interpreting it inappropriately, warns Aude Doody.

Historians disagree as to which work should be considered the first encyclopedia. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that many works have been lost and are only known from short descriptions or fragments. On the other hand, there is no binding definition of an encyclopedia, some historians also consider an encyclopedic approach in the sense of striving for comprehensiveness.

antiquity

The Greek philosopher Plato is named as a spiritual father of the encyclopedia. He did not write an encyclopedia himself, but with his Academy in Athens he committed himself to making education available to every intelligent young man. Only fragments have survived from an encyclopedic work by Plato's nephew Speusippus (died 338 BC). Aristotle was also said to have an encyclopedic approach, in the sense of comprehensive .

The Greeks are known for their intellectual explorations and philosophical originality. However, they did not summarize their knowledge in a single work. The Romans are considered to be the actual inventors of the encyclopedia. In the Roman Republic there was already the series of letters Praecepta ad filium (about 183 BC), with which Cato the Elder instructed his son.

Above all, the encyclopedia was created in the imperial period, since it needed the wide horizons of people who ruled an empire. The first of the actual encyclopedias were the Disciplinarum libri IX by Marcus Terentius Varro († 27 BC). The second encyclopedia was the Artes of the physician Aulus Cornelius Celsus (died c. AD 50). Varro was the first to combine the general education subjects that later became the liberal arts. In addition to those subjects that then became canon in the Middle Ages , he took up medicine and architecture. The Hebdomades vel de imaginibus are seven hundred short biographies of great Greeks and Romans; only a few fragments of this have survived, as well as the Discliplinarum libri . Varro had a great influence on authors of late antiquity.

Of paramount importance, however, was the Naturalis historia by the politician and naturalist Pliny . The administrator Pliny was used to seeing the world divided into units and sub-units. Written around AD 77, his work is now believed to be the only ancient encyclopedia that has survived in its entirety. In the Middle Ages they were found in almost every sophisticated library. What was special about her was the universality she claimed and repeatedly addressed. It also served Pliny as an explanation for the fact that he could only describe many things very briefly.

Another Roman encyclopedist with far-reaching influence was Martianus Capella of North Africa. Between AD 410 and 429 he wrote an encyclopedia, often called Liber de nuptiis Mercurii et Philologiae (“The Marriage of Philology with Mercury ”), written partly in verse. The seven bridesmaids corresponded to the chapters of the work, and these in turn corresponded to the seven liberal arts .

Early Middle Ages

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the politician Cassiodorus preserved parts of ancient knowledge in the early Middle Ages with his compilation Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum (AD 543–555) . To do this, he had retired to a monastery he had founded himself in southern Italy. While Cassiodorus was still separating the secular from the spiritual, two generations later Bishop Isidore of Seville integrated Christian teaching into ancient scholarship.

Isidore's encyclopedia Etymologiae (around 620) wanted to interpret the world by explaining terms and their origins. By discerning the true meaning of a word the reader was instructed in the faith. However, Isidor admitted that some words were chosen arbitrarily. Research has identified many of Isidore's templates. His own achievement was in selecting from them and delivering a clear, well-arranged exposition in plain Latin. Breaks in the text suggest that Isidor did not complete his work.

Rabanus Maurus , who was consecrated archbishop of Mainz in 847, compiled a work De universo , which largely adopted Isidore's text. Rabanus began each of his 22 chapters with a suitable passage from Isidore, leaving out much that he considered unnecessary for understanding the Scriptures. For him, this included the liberal arts in particular. Many later works of the Middle Ages also followed his example, beginning with God and the angels.

High and Late Middle Ages

The works of the European High Middle Ages (around 1050 to 1250) were based on the ancient and early medieval encyclopedias. Around 1230, Arnoldus Saxo compiled the Latin encyclopedia De finibus rerum naturalium . The largest encyclopedic work of the mid-13th century was Vincent de Beauvais 's Speculum maius , containing almost ten thousand chapters in eighty books. It covered nearly all subjects: in the first part, Speculum naturale , God and creation, including natural history; in the speculum doctrinale , practical moral action and the scholastic heritage; in the speculum historiale the history of man from creation to the thirteenth century. A fourth part, Speculum morale , was added after Vincent's death and was based primarily on Thomas Aquinas' works.

The southern Dutchman Jacob van Maerlant spread his encyclopedic knowledge across several works: In the Alexanderroman Alexanders Geesten (around 1260) he bound a thousand verses that make up a rhymed world atlas. In Der naturen bloeme (circa 1270) he dealt with nature, and in Spiegel historiael (circa 1285) with world history. He was the first European encyclopedist to write in a vernacular (non-Romance) language. His works are mainly adaptations of Latin models, such as De natura rerum by Thomas von Cantimpré and Speculum historiale by Vincent von Beauvais , but he omits many details, selects, adds content from other authors and draws to a small extent from his own knowledge of the world. For example, he moralized and believed in the magic power of precious stones. Nevertheless, Maerlant stands for a comparatively modern, critical and researching view of nature in the spirit of Albertus Magnus . One of the medieval forerunners of today's encyclopedias is the 13th-century work De proprietatibus rerum by Bartholomaeus Anglicus .

In the late Middle Ages and in the Renaissance (approx. 1300-1600), a representation that appeared more scientific and less based on Christianity was already partly used. Thus the anonymous Compendium philosophicae (around 1300) freed itself from the legends that had wandered through the encyclopedias since Pliny; the Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives , in De disciplinis , based his arguments on nature, not religious authority. Vives did not want to speculate about nature, but to observe nature in order to learn something practical for himself and those around him. Despite these approaches, miraculous beasts and monsters populated encyclopedias well into the 18th century, where they were unproblematically attributed to nature.

non-European cultures

Even more than the Western ones, the Chinese encyclopedias were compilations of important literature. Over the centuries they have been continued rather than renewed. Often intended primarily for the training of civil servants, they usually followed a traditional layout. The first known Chinese encyclopedia was the "Emperor's Mirror" Huang-lan , which was created around 220 AD by order of the emperor. Nothing has survived from this work.

The T'ung-tien , completed about 801, deals with statesmanship and economics and continued with supplements into the 20th century. One of the most important encyclopedias, Yü-hai , was compiled around 1267 and appeared in 240 printed volumes in 1738. The Tz'u-yüan (1915) is considered the first modern Chinese encyclopedia, and it set the direction for later works.

The Persian scholar and statesman Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Chwārizmi compiled an Arabic 'key to the sciences', Mafātīḥ al-ʿulūm , in 975–997 . He was undoubtedly familiar with the main features of the Greek intellectual world and sometimes referred to the works of Philo, Nicomachus or Euclid. His encyclopedia is divided into a 'native' Arabic part, including most of what is now considered humanities, and a 'foreign' part.

The Brothers of Purity in Basra (modern-day Iraq), a group of Neoplatonic philosophers close to the Ismāʿīlīya , were most active in 980-999 and collaborated on an encyclopedia. Their compilation is called Rasāʾil Iḫwān aṣ-Ṣafāʾ (“Entry of the Brothers of Purity”). They, too, knew the Greek scholars and had pronounced preferences. Conversely, there is little evidence that the Western encyclopedia authors knew the Arabic-Islamic sources. The Chinese encyclopedias, on the other hand, were separated from both Christian and Islamic cultures.

Early modern age

Margarita Philosophica by Gregor Reisch (1503) was a widely used general encyclopedia, a textbook on the seven liberal arts. It was the first encyclopedia to appear in print rather than in manuscript. Like the Encyclopaedia by Johannes Aventinus (1517) and the Encyclopaedia Cursus Philosophici by Johann Heinrich Alsted (1630), it followed a systematic order.

The Grand Dictionaire historique (1674) by Louis Moréri was the first large, national-language, alphabetical reference work on the subject areas of history, biography and geography. In its tradition stands the peculiar Dictionnaire historique et critique (1696/1697) by Pierre Bayle , which was originally intended to correct and supplement Moréri's work. Bayle provided an extremely detailed and critical body of comments on rather brief articles. Since Bayle primarily dealt with subjects that interested him personally, his work can be seen as an ego document , an intellectual autobiography. It was intended to be used alongside, not in place of, a general purpose encyclopedia.

If one thinks of encyclopedias today primarily in terms of biographical and historiographical knowledge and less of scientific knowledge, the opposite was the case around 1700. At that time the dictionnaires des arts et des sciences were created , dictionaries of the (mechanical, craft) arts and sciences. Biographical and historiographical information was largely missing. As dictionaries, unlike most earlier works, they broke with thematic arrangement. This new direction in the history of the encyclopedia began with Antoine Furetière 's Dictionnaire universel des arts et sciences (1690). Comparable were the Lexicon technicum (1704) by John Harris and then the Cyclopaedia (1728) by Ephraim Chambers .

But as a direct successor to these successful works, a further step was taken, bridging the gap between a scientific-philosophical and a biographical-historical reference work. Last but not least, the Universal-Lexicon (1732-1754) by Johann Heinrich Zedler , which is named in this sense, should be emphasized here. The major work, published in 64 volumes, was the first encyclopedia with biographies of people who were still alive.

the Age of Enlightenment

By far the most famous encyclopedia in history is the great French Encyclopédie (1751–1772, supplements to 1780). Although it hardly introduced any actual innovations, it was praised for its scope, the thematic breadth, the systematic substructure and the many illustrations, namely two thousand five hundred, while its competitors only had a few hundred illustrations. Nevertheless, it was less successful and influential than is often assumed, because of its sheer size alone, it reached relatively few readers compared, for example, to the widespread and repeatedly reprinted Cyclopaedia .

Above all, with its critical and worldly attitude, it is considered a jewel of the Enlightenment , the pan-European educational offensive. Attacks from the Church and difficulties with censorship overshadowed its creation, as did later disputes between editors Denis Diderot and Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert . Diderot and many of his co-authors, at various points in the encyclopedia, made criticisms of certain ideas in mainstream society. As such, the work was the result of the work of many encyclopedists and could only be finally completed thanks to the efforts of Louis de Jaucourt , who even hired secretaries at his own expense. The last ten volumes, most of which he wrote himself, contain fewer polemical references than the first seven, which may make them less interesting for modern readers.

In the English-speaking world, the Encyclopaedia Britannica , first published in Scotland, flourished in the United States from the 20th century. The first edition (1768-1771) consisted of three volumes and was rather modest in quality and success. The quality improvement of the second edition contributed to the success of the third, which already comprised 18 volumes. If the Encyclopaedia Britannica stood the test of time, while the great French Encyclopédie had its last, humble, and transformed successor in 1832, it was because of the editors' courage to innovate. In addition, political developments in Great Britain were calmer than in France, which was suffering the consequences of the 1789 revolution .

19th century

Around 1800 a new and successful type of encyclopedia appeared. It originated from the Konversationslexikon , which Renatus Gotthelf Löbel had initially helped to create. In 1808 his unfinished work, begun in 1796, was bought by Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus . It covered contemporary issues of politics and society to provide educated conversation in a socially diverse group. With the editions of 1824 and 1827, the F. A. Brockhaus publishing house began to prefer more timeless themes from history, and later also from technology and science, since the constant renewal of the volumes with current topics became too expensive.

In the Brockhaus , the topics were divided into many short articles, which allowed the encyclopedia to quickly provide information about a term. The Britannica , which initially consisted of long articles, did a similar thing . While the Brockhaus came from the humanities and later integrated the natural sciences, it was the other way around with the Britannica .

In that century the school system in European countries expanded considerably. Together with improvements in printing technology, this meant that more and more people could read. Around 1800 there were 470 publishing houses in the German-speaking world , a hundred years later there were 9,360 in the German Reich. Accordingly, encyclopedias were no longer printed in editions of several thousand, but in several tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands. From 1860 to 1900, encyclopedias strove for more equal treatment and standardization. The appreciation for statistical material was great.

In Germany, the Brockhaus , the Meyer , the Pierer and, for the Catholic public, the Herder , in particular, shared the market. Brockhaus and Meyer each had a third of the market share. At the end of the 19th century there were about fifty other publishers that offered encyclopedias. Some encyclopedias deliberately took their name from a famous predecessor, such as the Chambers' Encyclopaedia by the Chambers brothers, which was only reminiscent of Ephraim Chambers ' Cyclopaedia in name .

20th century

By 1900 most western countries had at least one extensive and recent encyclopedia. Some could boast a tradition of fifty or even a hundred years. Experts covered many subjects in the language of the country concerned. Articles were in alphabetical order and included biographies of living individuals, as well as illustrations, maps, cross-references, indices, and bibliographies at the end of longer articles. An encyclopedia that deviated from this concept did not survive long. But even the others only got past one or two editions if competent publishers stood behind them. Furthermore, revolutions and world wars could bring down good encyclopedias.

The First World War partially interrupted development, and in Germany, among other places, inflation initially made it difficult to resume. In the case of Meyer, for example, this led to the decision to reduce the Großer Meyer from 20 to twelve volumes, creating a new, medium-sized encyclopedia type. In the 1920s, the major encyclopedias addressed a much wider audience than before the war and placed even more value on factual presentation. The layout was more modern, there were more illustrations; at the Brockhaus (from 1928) colored pictures were glued in by hand. Advertising was expanded considerably, Brockhaus not only presented the product in customer magazines and information brochures, but also the idea and those involved; Market analyzes were introduced.

The totalitarian regimes presented a challenge of their own kind. For example, in National Socialist Germany (1933–1945), the employees of the Brockhaus publishing house were brought into line , and concessions had to be made to the official party examination committee . The Kleine Brockhaus , reissued in 1933, included updated biographies on Hitler, Göring and other Nazi greats, as well as new political terms. The party ideologues were not satisfied with this, but the publisher referred to the international reputation of the Brockhaus , which should not be jeopardized for economic reasons either. The Bibliographic Institute was much less reserved. Its board members quickly joined the NSDAP, and in 1939 Meyer was advertised as the only large encyclopedia recommended by the party officials.

In the decades following World War II , encyclopedias and their publishers boomed. In the German-speaking world, this meant that the two most important encyclopedia publishers, F. A. Brockhaus and Bibliographic Institute (Meyer), experienced strong competition from other publishers. Large publishers in particular opened up a broad readership with popular reference works and a considerable market share in small and medium-sized encyclopedias. In 1972, Piper brought out a youth encyclopedia, Bertelsmann came out with the ten-volume encyclopedia (1972, with additional thematic volumes), and Droemer-Knaur two years later, also with a ten-volume work. The retail chains Kaufhof and Tchibo offered one-volume encyclopedias. Brockhaus and Bibliographic Institute merged in 1984; in 1988 Langenscheidt became the majority shareholder, responding to a generous offer from Robert Maxwell .

Electronic Encyclopedias

As early as the first half of the 20th century, there were ideas for a new type of encyclopedia. For example, around 1938 the science fiction author HG Wells dreamed of a World Encyclopaedia that would not offer hastily written articles, but rather carefully compiled excerpts that were constantly checked by experts. Wells believed in the then-new microfilm as an inexpensive and universal medium.

“This world encyclopedia would be the spiritual background of every intelligent person in the world. It would be alive and growing and constantly changing through revision, expansion and replacement by the original thinkers around the world. Every university and research institution should feed them. Any fresh mind should be put in touch with their permanent editorial organization. And on the other hand, their content would be the usual source for school and college teaching assignments, for fact verification and proposition testing – anywhere in the world.”

Thirty years later, encyclopedia expert Robert Collison commented that the perfect encyclopedia might never materialize in the form Wells envisioned. This perfect encyclopedia already exists in the imperfect form of the large libraries, with millions of books indexed and cataloged . A host of librarians and bibliographers made all of this available to the public, either individuals or groups. Authors and editors delivered new books and articles daily.

In the 1980s, personal computers made their way into private households. But the electronic or digital challenge was not recognized by the encyclopedia publishers for a long time. The foreword to the 26-volume Dutch Winkler Prins from 1990 states that the editors have examined the possible application of new, electronic media. But for the background knowledge that this encyclopedia offers, the classic book form is and will remain the most handy medium.

In 1985, the software company Microsoft wanted to publish an encyclopedia on CD-ROM . However, the desired partner, Encyclopaedia Britannica , turned down a collaboration. At that time, only four to five percent of US households had a computer, and the Britannica publishing house also feared for the intellectual image that its own encyclopedia had built up. In the 1990s came the big breakthrough of electronic encyclopedias. However , Brockhaus also saw a downward trend in 2005/2006: encyclopedias would be printed again. He referred to himself as well as to the French Encyclopædia Universalis (2002) and the Encyclopaedia Britannica (2002/2003). A permanent double-track development with electronic and print encyclopedias can be assumed.

CD-ROM Encyclopedias

In 1985 a pure text encyclopedia appeared on CD-ROM , the Academic American Encyclopedia by Grolier, based on the DOS operating system. Then in April 1989 the Britannica publishing house brought out a CD-ROM encyclopaedia, although not the flagship under its own name. Rather, it published a multimedia version of the acquired Compton's Encyclopaedia .

Microsoft, for its part, bought the expiring Funk and Wagnalls Standard Reference Encyclopedia in 1989 , which had been sold cheaply in supermarkets. The texts were refreshed and expanded with a very small staff, and pictures and audio files were also added. In 1993 they came out as Microsoft Encarta . Customers received them together with the Windows computer operating system , otherwise they cost a hundred dollars. At that time, twenty percent of US households already owned a computer.

Britannica followed a year later with a CD-ROM version of Encyclopaedia Britannica . They were available as an add-on to the print version or for a whopping $1,200. By 1996, Britannica dropped the price to $200, but by then Microsoft Encarta was dominating the digital encyclopedia market. Britannica had been so confident in the reputation of its encyclopedia that it had not taken the newcomer seriously. From 1990 to 1996, revenue from the Encyclopaedia Britannica fell from $650 million to just $325 million a year. The owner sold it to a Swiss investor in 1996 for 135 million.

Internet encyclopedias

As early as 1983, the Academic American Encyclopedia appeared, the first encyclopedia to be presented online and offered its content over commercial data networks such as CompuServe . When the Internet became a real mass market, the first online encyclopedias were the Academic American Encyclopedia and the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1995 .

Those encyclopedias could only be accessed for a fee. Typically, the customer paid an annual subscription for access. In addition, there were suggestions for online encyclopedias based on free knowledge : the content should be editable and redistributable freely and free of charge under certain conditions, such as naming the source. This thought did not appear explicitly in Rick Gates' 1993 call for an Internet Encyclopedia , but it did in Richard Stallman 's announcement (1999) of a Free Universal Encyclopedia as part of the GNU software project.

When Internet entrepreneur Jimmy Wales and his employee Larry Sanger put Nupedia online in 2000 , the reaction was small. A "free" Internet encyclopedia only received any notable interest when Wales and Sanger introduced the wiki principle. With such a website, the reader himself can make changes directly. January 15, 2001 is considered the birthday of Wikipedia , which has since grown into by far the largest encyclopedia. It is mostly written by volunteer authors, and the costs of running the server are covered by donations to the operating foundation, the non-profit Wikimedia Foundation .

Initial doubts about the reliability of Wikipedia were countered by several studies that found the error rate to be comparable to that in traditional encyclopedias. Comparisons with specialist encyclopedias and specialist literature are more critical. However, quality is not only about factual correctness, as historian Roy Rosenzweig pointed out in 2006, but also about good style and conciseness . Wikipedia often leaves a lot to be desired here.

In addition to Wikipedia , there are other online encyclopedias, some based on other principles. For example, Citizendium (since 2006) requires authors to be registered by name, who should be recognized experts in their subject. Google Knol (2008-2011) transcends the boundaries of an encyclopedia and gives authors the greatest freedom in content and ownership of their texts. Knowledge.de (since 2000) has a wide range of content that is not necessarily encyclopedic, with quizzes and lots of multimedia.

As a result, the demand for print encyclopedias and fee-based electronic encyclopedias has fallen sharply. In 2009, Microsoft abandoned Encarta , which Britannica Online is struggling to survive on ads. In doing so, it has adapted in part to Wikipedia , since it is freely accessible and encourages readers to make improvements, although these are controlled by employees. The Brockhaus was taken over by the Bertelsmann subsidiary Knowledge Media in 2009 ; the Federal Cartel Office had approved the takeover despite Bertelsmann's dominant position because the encyclopedia market had shrunk to a trivial market.

subject encyclopedias

The word general in general reference work refers both to the general audience and to the generality (universality) of the content. Specialist encyclopedias (also called special encyclopedias) are limited to a specific subject such as psychology or a topic such as dinosaurs. Often, although not necessarily, they address a specialist audience rather than a general audience, because specialists are particularly interested in the subject. To distinguish it from the specialist encyclopedia, the general encyclopedia is sometimes also called universal encyclopedia. However, if one defines an encyclopedia as an interdisciplinary reference work, then universal encyclopedia is a pleonasm and subject encyclopedia an oxymoron .

Although most specialist encyclopedias, like the general encyclopedias, are arranged in alphabetical order, the subject encyclopedias are arranged a little more by subject. However, subject-specific reference works in a thematic arrangement are usually given the designation manual . The systematic arrangement is useful if the subject already follows a systematic approach, such as biology with its binary nomenclature .

The Summa de vitiis et virtutibus (12th century) can be regarded as perhaps the first specialist encyclopedia . In it, Raoul Ardent treated theology, Christ and salvation, practical and ascetic life, the four cardinal virtues, human conduct.

Apart from a few exceptions, specialist encyclopedias have been created since the 18th century in the field of biography, such as the Allgemeine Gelehrten-Lexicon (1750/1751). Specialist encyclopedias often followed the rise of the relevant subject, such as the Dictionary of Chemistry (1795) in the late 18th century and many other chemistry dictionaries afterwards. The wealth of publications was only comparable in the field of music, starting with the Musikalisches Lexikon (1732) by the composer Johann Gottfried Walther . The Paulys Realencyclopedia of Classical Antiquities (1837-1864, 1890-1978) is unparalleled in its field.

One of the best-known popular specialist encyclopedias was Brehm's Thierleben , founded by the non-fiction author Alfred Brehm in 1864. It was published in the Bibliographic Institute , which also published Meyer's Konversations-Lexikon . The large edition from the 1870s already had 1,800 illustrations on over 6,600 pages and additional plates, which were also available separately, some in colour. The third edition 1890-1893 sold 220,000 copies. In 1911 animal painting and nature photography brought a new level of depiction. The work was continued, eventually also digitally, into the 21st century.

From the end of the 19th century encyclopedias about certain countries or regions also appeared. The geographical encyclopedias are to be distinguished from the national encyclopedias , which focus on their own country. Examples are the German Colonial Lexicon (1920), The Modern Encyclopaedia of Australia and New Zealand (1964) and the Magyar életrajzi lexikon (1967–1969). The last volume of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1st edition) dealt exclusively with the Soviet Union; it was published in 1950 as a two-volume encyclopedia of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the GDR. The Fischer World Almanac (1959–2019) covers the countries of the world in alphabetical order, in up-to-date volumes per year.

The largest encyclopedia ever printed in German had 242 volumes. The work entitled Economic Encyclopedia was published between 1773 and 1858 largely by Johann Georg Krünitz . The University of Trier has completely digitized this work and made it available online.

structure and order

Until the early modern period, encyclopedias were more like non-fiction or textbooks. The distinction between encyclopedias and dictionaries appears to be even more difficult . There is no sharp distinction between facts and words, because no language dictionary can do without factual explanations, no specialist dictionary like an encyclopedia can do without linguistic references.

The individual contributions to an encyclopedia are arranged either alphabetically or according to another system. In the latter case one often speaks of a "systematic" arrangement, although the alphabet can also be regarded as a system and the term "non-alphabetical" would therefore be more correct. The systematically arranged encyclopedias can also be distinguished according to whether the classification is more pragmatic or even arbitrary, or whether there is a philosophical system behind it. The term "thematic" is often used instead of "systematic".

Systematic arrangement

For the true scholar, the systematic arrangement alone is satisfactory, wrote Robert Collison, because it juxtaposes closely related themes. He assumed that the encyclopedia would be read as a whole, or at least in large chunks. In nature, however, there are no compelling connections. Systems are arbitrary because they come about through a human reflection process. Nevertheless, a systematic presentation has didactic value if it is logical and practical.

Pliny , for example, used many different principles of order. In geography he begins with the familiar shoreline of Europe and then progresses to more exotic continents; he treated people before animals because people were more important; in zoology he begins with the largest animals; in marine life with those of the Indian Ocean, because these are the most numerous. The first Roman tree covered is the grapevine, as it is the most useful. Artists appear in chronological order, gems by price.

A systematic arrangement was traditionally the usual one, until since the 17th/18th Century the alphabetical prevailed. Nevertheless, there were still some larger non-alphabetical works afterwards, such as the unfinished Contemporary Culture (1905–1926), the French Bordas Encyclopédie from 1971 and the Eerste Nederlandse Systematisch Ingerichte Encyclopaedie (ENSIE, 1946–1960). In the originally ten-volume ENSIE, individual major contributions signed by name are listed according to thematic order. To search for a single item, you have to use the index, which in turn is a kind of encyclopedia in itself.

After the encyclopedias were mostly arranged alphabetically, many authors still included a knowledge system in the foreword or in the introduction. The Encyclopaedia Britannica (like Brockhaus 1958) has had an introductory volume called Propaedia since 1974 . In it, the editor, Mortimer Adler , introduced the advantages of a thematic system. You can use it to find an object even if you don't know the name. The volume breaks down the knowledge: first into ten major themes, within these into a large number of sections. At the end of the sections, reference was made to corresponding concrete articles. Later, however, the Encyclopaedia Britannica added two more index volumes. The Propaedia is said to serve primarily to show which topics are covered, while the index shows where they are covered.

A 1985 survey of American academic libraries found that 77 percent found the new layout of the Britannica less useful than the old. One reply commented that the Britannica comes with a four-page manual. "Anything that needs so much explanation is too damn complicated."

Not an encyclopedia per se, but of an encyclopaedic nature are series of non-fiction books in which many different topics are treated according to a uniform concept. The French series Que sais-je , founded in 1941, is one of the best-known internationally . with over three thousand titles. In Germany, C. H. Beck publishes the series C. H. Beck Knowledge .

Alphabetical arrangement

The first volume, with a green stripe, is the systematic Propaedia (“Outline of Knowledge”) with its references to Micropaedia and Macropaedia .

Then follows, with red stripes, the Micropaedia ("Ready Reference"), a classic short-article encyclopedia with approx. 65,000 articles.

The Macropaedia ("Knowledge in Depth"), bottom board, covers major issues in about seven hundred articles.

Finally, behind the Macropaedia , with blue stripes, is the two-volume, alphabetical index with references to Micropaedia and Macropaedia .

For a long time there were only a few texts in alphabetical order. In the Middle Ages, these were mainly glossaries , i.e. short collections of words, or lists of medicines, for example. Glossaries have been in existence since the 7th century, when readers wrote down difficult words on individual sheets (by first letter) and then made a list out of them. The alphabetical arrangement was usually only followed after the first or at most the third letter, whereby one did not proceed very consistently. In addition, many words did not yet have a uniform spelling . Even in the 13th century the strict alphabetical order was still rare.

Some of the few early alphabetical encyclopedias mentioned include: De significatu verborum (2nd half of the 2nd century) by Marcus Verrius Flaccus ; Liber glossarum (8th century) by Ansileubus ; and most notably the Suda (c. 1000) from the Byzantine Empire. However, they have more the character of language dictionaries ; significantly, the entries in the Suda are usually very short and often deal with linguistic issues, such as idioms. After the alphabetical works of the 17th century, it was above all the great French Encyclopédie (1751–1772) that finally associated the term “encyclopedia” with the alphabetical arrangement.

Ulrich Johannes Schneider points out that encyclopedias previously followed the “university and academic culture of disposing of knowledge through systematization and hierarchization”. However, the alphabetical arrangement decoupled the encyclopedias from this. It is factual and weights the content neutrally. The alphabetical arrangement spread because it facilitated quick access. One of these encyclopedias, the Grote Oosthoek , said in the preface in 1977 that it was a matter of utility, not of scientific principle. Fast information from foreign specialist areas is obtained through a large wealth of keywords, which saves time and energy. According to a 1985 survey, ready reference is the most important purpose of an encyclopedia, while systematic self-study was mentioned much less frequently.

It was easier for the editor when a larger work was divided by topic. A thematically delimited volume could easily be planned independently of others. In the alphabetical order, on the other hand, it must (at least in theory) be clear from the start how the content will be distributed among the volumes. You had to know all the lemmas (keywords) and agree on the cross-references.

Even those encyclopedists who advocated the systematic classification opted for the alphabetical arrangement for practical reasons. This included Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert of the great French Encyclopédie . A later editor and arranger of this work, Charles-Joseph Panckoucke , wished to re-establish a thematic arrangement. But he just sorted the articles into different subject areas, and within those subject areas, the articles appeared in alphabetical order. This Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières was thus a collection of 39 subject dictionaries.

item length

Even within the alphabetically arranged works, there are still a number of different options. Articles on individual topics can be long or short. The original Konversationslexikon Brockhaus is the typical example of a short-article encyclopedia, with many short articles describing a single subject. Cross- references to other articles or individual summarizing contributions provide the context .

Long-article encyclopedias, on the other hand, contain large textbook-like articles on relatively broad topics. An example is the part of the Encyclopaedia Britannica called Macropaedia in the 1970s to 1990s. Here it is not always clear for the reader in which major article he has to look for the subject that interests him. Such an encyclopedia can only be used as a reference work if it has an index , similar to a systematic arrangement.

Dennis de Coetlogon may have had the idea of using long, overviewing articles for the first time with his Universal history . It probably served as a model for the Encyclopaedia Britannica (which originally had long articles, called treatises or dissertations ). Longer articles were also a counter-movement to the lexicon, which was becoming more and more definitional and keyword-like. However, long articles could not only result from a conscious departure from the rather short dictionarynaire articles . Sometimes they were the result of a weak editorial policy that did not restrict the authors' desire to write or simply copied texts.

| plant | item name | length in sides | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zedler (1732–1754) | "Wolf Philosophy" | 175 | |

| Universal history (1745) | geography | 113 | The work deliberately consisted of longer treatises (treats). |

| Encyclopedia Britannica (1768–1771) | "surgery" | 238 | |

| Encyclopedia Britannica (1776–1784) | "medicine" | 309 | |

| Economic Encyclopedia (1773–1858) | "Mill" | 1291 | The article covers all of Volume 95 and most of Volume 96, both published in 1804. |

| Ersch-Gruber (1818–1889) | "Greece" | 3668 | The article spans eight volumes. |

| Encyclopedia Britannica (1974) | "United States" | 310 | Created by combining the articles on the individual member states. |

| Wikipedia in German (November 2020) | " Chronicle of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States " | 392 (PDF; 1,564,136 bytes) |

Internal tools

Various tools have been developed over time for the practical use of an encyclopedia. Even in ancient times it was common practice to divide a long text into chapters. Corresponding tables of contents, on the other hand, are a relatively late development. They were created from the titles of the works. Before the 12th century they were still very rare and only became common in the 13th century.

Thus the Naturalis historia has a summarium written by Pliny , an overview. In some manuscripts the summarium is found undivided at the beginning, sometimes broken up into the individual books, as was probably most practical in the age of scrolls. Sometimes the text is both at the beginning and again later before the individual books. How Pliny himself handled it can no longer be determined today. While Pliny described the content of the work in prose, some later printed editions made a table out of it, similar to a modern table of contents. They were quite free with the text and adapted it to the presumed needs of the readers.

| Print from 1480 (Beroaldo) | Budé edition from 1950 |

|

The twenty-sixth book contains |

BOOK 26 CONTAINS |

Indexes , that is registers of headwords, also appeared in the 13th century and spread rapidly. In an encyclopedia, Antonio Zara first used a kind of index in his Anatomia ingeniorum et scientiarum (1614); really useful indices did not appear in encyclopedias until the 19th century.

One of the first cross- referenced works was the Fons memorabilium by Domenico Bandini (ca. 1440). They became common in the 18th century at the latest. In the 20th century, following the example of Brockhaus , some encyclopedias used an arrow symbol to implement the reference. Hyperlinks are used in the digital age .

Content balance

A recurring theme in research is the balance between subject areas in an encyclopedia. This balance is missing, for example, when the story or biography is given a lot of space in a work, while natural sciences and technology are given far less space. In a specialist encyclopedia , the lack of balance is criticized when, for example, political history is dealt with much more extensively than social history in a work on classical studies.

Sometimes the criticism refers to individual articles, measuring which lemma has received more space than another. For example, Harvey Einbinder found the 1963 Encyclopaedia Britannica article on William Benton noteworthy. According to the encyclopedia, this American politician has become "a champion of freedom for the entire world" in the Senate. The article is longer than the one about former Vice President Richard Nixon ; as Einbinder surmises, because Benton was also editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica . Einbinder also criticized the fact that the "Music" article praised Béla Bartok and Heinrich Schütz, but these composers did not receive their own articles.

Even pre-modern encyclopedias generally had a universal claim. Nevertheless, the interests or the abilities of the author often brought with them a limitation. The Naturalis historia included treatises on ethnology and art, but the focus was on areas of knowledge that are now classified as scientific. In the 18th century, universal encyclopedias began to blur the distinction between more humanistic and more scientific works. In some cases, one could still see the origin of a work, or the editor deliberately decided to sharpen the profile through a certain area or a certain approach: Ersch-Gruber followed the historical approach because of its clarity, whereas Meyer preferred that scientific.

The question of balance is particularly important in works for which the reader has to pay. He is likely to be dissatisfied if, in his opinion, a universal encyclopedia leaves too much room for topics that are of little personal interest to him, but which he also pays for. Robert Collison points to the irony that readers have wanted the most complete outlines possible and have "paid unquestioningly for millions of words they will probably never read," while the encyclopedia makers have also strived for completeness, writing entries on small topics that hardly anyone reads.

However, the balance is still discussed even in freely accessible encyclopedias such as Wikipedia . For example, it is about the question of whether it says something about the seriousness of the work as a whole if themes from pop culture (allegedly or actually) are represented above average. At least, as the historian Roy Rosenzweig emphasized , the balance is strongly dependent on which continent and which social class the authors come from.

Information in traditional encyclopedias can be evaluated by measures related to a quality dimension such as authority , completeness, format , objectivity , style , timeliness , and uniqueness .

Content aspects

languages

In the West , Latin was the language of education and thus of encyclopedias for a long time. This had the advantage that the encyclopedias could also be read in countries other than the country of origin. However, this made them inaccessible to the vast majority of the population. From about the beginning of the 13th century, knowledge also reached the people in their languages. French comes first, with Middle High German second in Europe since about 1300 . Women in particular were more likely to impart knowledge in the vernacular. At the end of the 15th century, vernacular encyclopedias were no longer a risk, but routine.

Some encyclopedias have been translated, such as Imago mundi (c. 1122) by Honorius Augustodunensis into French , Italian and Spanish . De natura rerum (ca. 1228–1244) received a translation into Flemish and German, the Speculum maius (mid-13th century) into French, Spanish, German and Dutch. Later, when Latin played a less important role, successful encyclopedias were translated from one vernacular to another. From 1700 it was unthinkable to publish another encyclopedia in Latin.

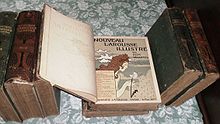

In the 19th century, for example, Brockhaus and Larousse , especially the smaller editions, served as models for encyclopedias in other languages or were translated into them. However, this had its limits, since the content had to be adapted to the respective language or country. One example is the Encyclopedia Americana (1827-1829), another the Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron (1890-1906), a short-article encyclopedia in Russian co-edited by Brockhaus-Verlag. Despite the adjustments, reviewers in both cases criticized that American and Russian history and culture had not been sufficiently taken into account.

Classification in the knowledge context

Scientific research is primarily concerned with human nature and actions. Depending on the subject, the basis is then, for example, natural phenomena, experiments, surveys or historical sources. Building on this, scientists write specialist literature or they reflect on other specialist literature in their work. Only after this actually scientific, i.e. research work, do aids come into play, such as introductory reading, atlases or dictionaries. This sequence of sources, specialist literature and aids is called primary , secondary and tertiary sources .

Encyclopedias are therefore tools that are intended to give the reader initial access to a topic. The same applies to textbooks and dictionaries, which are also related to encyclopedias historically and in terms of their literary genre. This in turn results in the character of encyclopedias and their use in the knowledge context.

The fact that encyclopedias are at the end of the knowledge production has the advantage that the statements usually represent already established and hardly disputed knowledge. However, this also has the disadvantage that new or unconventional ideas have been filtered out. In addition, errors or oversimplifications may have crept in from the basics to the specialist literature and the tools. For these reasons, it has been discussed time and again whether general encyclopedias may be cited by schoolchildren or students as an authority.

At the university, there is a widespread opinion that general reference works should not be cited in academic papers. According to Einbinder, some teachers and professors found that the Encyclopaedia Britannica was not a reliable source of information; they warned their students not to blindly incorporate this material into their own homework. On the other hand, Thomas Keiderling says in his history of the Brockhaus that in the 1920s scientists considered this encyclopedia to be citable.

style

The linguistic style of an encyclopedia depends on the purpose of the work and sometimes on the personal taste of the author. In the works of antiquity it is often recognizable that they were textbooks or non-fiction books and were originally compiled from such. For example, Pliny says in the section on insects:

“But among them all, the first place belongs to the bees, and justly also an extraordinary admiration, since they were created solely from the animal species [insects] for the sake of man. They collect honey, the sweetest, finest, and most wholesome juice, form combs and wax for a thousand uses in life, are industrious, complete their works, have a state, hold councils in their affairs, but stand in droves under leaders and, what is most They deserve admiration, they even have manners, being neither tame nor savage.”

In medieval Europe, vernacular works were written in rhyme so that readers could absorb and remember the content more easily. An example from Der naturen bloeme by Jacob van Maerlant , c.1270:

|

Ay, ghi edele ridders, ghi heren, |

Oh you noble knights, you lords, |

Such modes of representation classify the object in a larger, also philosophical context. Ratings can easily creep in that may well have been intentional. In the great French Encyclopédie , the article "Philosophe" (philosopher) was sometimes ironic, sometimes pathetic:

“Nothing is easier nowadays than to be called a philosopher; a life of obscurity, a few profound utterances, a little erudition are enough to outwit those who bestow that name on people who do not deserve it […] The philosopher, however, untangles things as much as possible, & and anticipates them & and knowingly submits: he is, so to speak, a clock that sometimes winds itself […] The philosopher does not act from his passions but from deliberation; he travels by night, but a flame precedes him.”

In the 19th century, the style later known as "encyclopaedic" emerged. Linguistically, it cannot be clearly distinguished from other genres such as academic essays. The author is made invisible, passive constructions are used, and there is a tendency to generalize. "An overall expository character of the articles" is also typical, writes Ulrike Spree. General encyclopedias try to use whole sentences, usually only the first sentence of an article is missing the verb. In addition to the lemma itself, numerous other words are abbreviated. An example from the Brockhaus Encyclopedia :

" Encyclopedia [French, from Medieval Latin encyclopaedia "Basic teaching of all science . and arts«, from Greek enkýklios paideía, "circle of education"] the , -/...'di|en , the written and complex representation of the entire knowledge or the knowledge of a special field. According to today's understanding, an E. is a comprehensive reference medium whose keywords are in alphabet. Inform order about all areas of knowledge […]”

The understanding of science is mostly empirical and positivistic, not deductive . Although there are references in alphabetical reference works, the articles are not contextualized. The reader must first establish this context. One and the same text can evoke different associations in different readers. Although a certain telegram style is recognizable, there is also the opposite tendency for didactic reasons. With increased redundancy, clarity, and examples, articles approach textbooks.

neutrality

Usually, encyclopedias claim to be objective and not speak for any interest group or party. In the 19th century, for example, it was thought possible to fathom and convey absolute truth, even if individual errors were possible. Rarely have encyclopedists like Denis Diderot wanted to elevate doubt to a methodical principle.

truth claim

A number of positions are conceivable within the truth claim:

- A compilation of older works refers to a long tradition that stands for the correctness of the statements. This attitude was typical in the first half of the 18th century.

- Works can dispense with ideological positioning and claim that they are a compilation.

- Conversational dictionaries in particular try to avoid attitudes that are perceived as extreme.

- A neutral stance attempts to weigh up and take a stance above the parties.

- A pluralistic approach allows different interest groups to have their say in different articles.

Or encyclopedias explicitly side with a particular group, such as the educated classes, the working class, or the Catholics. Interests should be taken into account and errors corrected. Even then, however, the claim to universal validity is not abandoned.

Encyclopedias are usually not directed against the existing basic ideas in their society. Pierre Bayle and Denis Diderot were exceptions. Later, for example, the anti-monarchical Grand Dictionnaire Universel du XIXe siècle by Larousse , the conservative Staats- und Gesellschaftslexikon by Hermann Wagener , the liberal Staatslexikon (1834–1843) by Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker , and the social-democratic people all had decidedly political objectives -Lexikon from 1894. However, such trend writings were rather rare.

examples and allegations

When historians try to learn how people thought about something in a particular era, they often consult the encyclopedias of the time. However, a statement does not necessarily have to be actually representative of society, perhaps it merely reflects the opinion of the author, the editors or a certain segment of the population.

Some examples:

- William Smellie , a fair-skinned Scotsman, wrote of Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia) in the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768–1771) : "The inhabitants are black, or nearly so, but they are not so ugly as the Negroes."

- In 1910/1911 the Encyclopaedia Britannica said that "negroes" were mentally inferior to whites. It is true that Negro children are intelligent and bright, but from puberty onwards Negroes are primarily interested in sex-related matters.

- The great French Encyclopédie also allowed itself discriminatory opinions: "All ugly people are crude, superstitious and stupid", wrote Denis Diderot in the article "Humaine, Espèce" (Species of Man). Furthermore, the Chinese are peaceful and submissive, the Swedes have almost no conception of religion, and the Lapps and Danes worship a fat black cat. The Europeans are "the most beautiful and well-proportioned" people on earth. Such national stereotypes are even very common in reference works of the 18th century.

- In “Homosexuality” in 1955, the Volks-Brockhaus referred to the legislation of the time in the Federal Republic of Germany, according to which “fornication between men is punished with imprisonment, under aggravating circumstances with penitentiary”. In addition, homosexuality “often can be cured by psychotherapy”.

- Two authors from the 1980s found that general encyclopedias provide less information about famous women than famous men and therefore reproduce sexist role models in society.

Harvey Einbinder lists a variety of Encyclopaedia Britannica articles that he doubts are neutral or objective. Modern artists would be summarily declared worthless, important plot elements would be omitted out of prudery, for example in the play Lysistrata , or sexual themes would be hidden behind technical terms. Incomprehensibly, the murder of the Jews was not associated with National Socialist ideology, and the moral aspect of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was hardly discussed. The latter is done according to his assumption in order to spare the Americans an unpleasant topic.

The publishers of encyclopedias sometimes had explicit socio-political goals. For example, the supplementary volume from 1801 to 1803 to the Encyclopaedia Britannica in particular dealt with the French Revolution in a combative manner. Dedications to the reigning monarch were not uncommon, but at the time they said:

“The French Encyclopédie has been accused, and rightly so, of having spread widely the seeds of anarchy and atheism. If the Encyclopaedia Britannica combats, in any way, the tendency of this plague-carrying work, these two volumes will not be entirely unworthy of Your Majesty 's favor."

Later in the 19th century , by his own admission, Meyer advocated intellectual equality for people, enabling readers to live a better life. However, revolutionary thinking should not be encouraged. In contrast to this rather liberal attitude, Sparner's Illustrated Conversations Lexicon (1870) wanted to have a socially disciplining effect on the lower class.

In general, encyclopedias are often accused of not being neutral. Some critics considered the Encyclopaedia Britannica pro-Catholic, others anti-Church. Around 1970, some reviewers praised the Brockhaus for its allegedly conservative undertone compared to the "left-leaning" Meyer , while others said it was exactly the other way around. Thomas Keiderling finds it problematic at all to make blanket judgments of this kind.

Large-scale ideological systems

In 1949, the Dutch Katholieke Encyclopedie deliberately did not place itself in the tradition of the Enlightenment, but of the Christian Middle Ages. Like its sister, the university, the encyclopedia came from a Catholic family. A prospectus dating back to 1932 calls impartiality dangerous, especially in an encyclopedia. After all, topics such as "Spiritism", "Freudianism", "Freemasonry", "Protestantism" or "Liberalism" need critical treatment and absolute rejection. “It is clear that neutrality cannot take a position. But numerous topics cannot be judged without a solid basis.” In the so-called neutral encyclopedias, Buddha receives more attention than Jesus Christ.

The Enciclopedia Italiana (1929-1936) was written in the period of fascism and the dictator Benito Mussolini had more or less personally contributed to the topic of "fascism" (cf. La Dottrina Del Fascismo ). In general, however, the work was international and objective. In Germany, the Brockhaus had to adapt politically in the last parts of its large edition from 1928 to 1935. The so-called “brown Meyer” from 1936 to 1942 (unfinished) is considered to have a distinctly National Socialist tinge.

The Great Soviet Encyclopedia was not aimed at the masses of workers and peasants, but at the “ main cadres who are pursuing Soviet construction”. In the foreword of 1926 she described her political orientation as follows:

"In the earlier encyclopedias, different - sometimes contradictory - worldviews existed side by side. In contrast, for the Soviet Encyclopedia, a clear worldview is absolutely necessary, and that is the strictly materialistic worldview. Our worldview is dialectical materialism . The field of social sciences, with regard to the illumination of the past as well as the present, is already extensively worked out on the basis of the consistent application of the dialectical method of Marx-Lenin ; in the field of natural and exact sciences, the editors will be careful to pursue the point of view of dialectical materialism [...]"

Even after publication, a Soviet encyclopedia had to be changed if a person suddenly became politically undesirable. When Lavrenti Beria was deposed in 1953, buyers of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia were sent a sheet with information about the Bering Sea, among other things, to be pasted in place of the old page with Beria.

Furnishing

scope

Traditionally, encyclopedias have tended to be of limited scope. Modern book editions of ancient or medieval encyclopedias are usually limited to one or a few volumes. For example, the Naturalis historia , monumental for antiquity , had five volumes in an edition around 1900. According to his own count, the work consisted of 37 libri (books), whereby a "book" is to be understood here as a chapter in terms of scope. The Etymologiae of Isidor make up a more or less thick book, depending on the edition.

Multi-volume encyclopedias only appeared in the 18th century, but at the same time there were always reference works in just one or a few volumes. In the 19th and 20th centuries, when encyclopedias became widespread, these found far more buyers than the large editions. For the 20th century, Thomas Keiderling uses a classification of small editions with one to four volumes, medium-sized editions of five to twelve volumes and large ones over that. However, for a more precise comparison of the scope, book formats, number of pages, font size, etc. must also be taken into account.

The Chinese work Yongle Dadian (also: Yung-lo ta-tien ) is sometimes listed as the largest encyclopedia in history. Dating from the 15th century, it contained 22,937 books on more than five hundred thousand pages. However, it was more a textbook collection compiled from older texts.

For a long time, the most extensive reference work was the Zedler with its 64 volumes. As a result, this mammoth work was unaffordable for many buyers, who could only come from a small, wealthy upper class anyway. Even many reading societies have not bought the Zedler .

In the 19th century, the Ersch-Gruber was the largest general encyclopedia. The work, begun in 1818, was not completed, however, after 167 volumes the new publisher (Brockhaus) gave up in 1889. The largest complete printed encyclopedia then became the Spanish -language Espasa in the 20th century, with a total of ninety volumes. The major works of the 18th and 19th centuries appear more extensive than those of the 20th century with their 20-30 volumes, but the much thinner paper of the later works must be taken into account.

run lengths

A popular encyclopedia such as Isidor's Etymologiae contained over a thousand manuscripts in the Middle Ages. The Elucidiarium of Honorius Augustodunensis existed in more than 380 manuscripts.

According to Jeff Loveland, in the 18th century about 200 to 300 copies of an encyclopedia sold; According to Ulrike Spree, however, the edition was 2000-4000 copies. Presumably only the 1500 subscription copies of the Zedler (1737) were purchased, i.e. those that wealthy customers had previously ordered. The first edition of the (then three-volume) Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768–1771) sold a total of three thousand copies, and the 18-volume third edition (1787–1797) sold thirteen thousand.

The 19th century saw significantly higher circulations. The Encyclopaedia Britannica in the 7th edition (1828) had 30,000 copies, Meyers Conversations-Lexikon had 70,000 subscribers in 1848/1849. However, since publication was slow and the volume count was high, this dwindled to under forty thousand. The 2nd edition of the Chambers Encyclopaedia sold over 465,000 sets in Great Britain alone in 1874-1888 .

Brockhaus sold 91,000 copies of its 13th edition (1882–1887), and more than 300,000 of the 14th edition up until 1913. The 17th edition of the great Brockhaus from 1966 had a total circulation of 240,000 copies (complete sets). However, Brockhaus experienced strong competition in the field of smaller dictionaries. Sales of the one-volume Volks-Brockhaus from 1955 were sluggish: it cost DM 19.80, while Bertelsmann put its Volkslexikon on the market for DM 11.80 andsold a million copies through its Lesering .

In the GDR , the eight-volume Meyers Neues Lexikon (1961-1964) had a total circulation of 150,000 copies, the two-volume edition came in 1956-1958 in three editions to 300,000 copies. Although the GDR was significantly smaller than the Federal Republic, the VEB Bibliographic Institute had no competition.

A lack of competition also led to high circulations in relation to the size of the population in other small countries, including western ones. The six-volume Uj Magyar Lexicon was published in communist Hungary in 1959-1962 in 250,000 copies. In Norway, the fifteen -volume Store Norske sold 250,000 copies from 1977 to 2011 to a population of just four million Norwegians.

Only "a few thousand copies" of the 21st edition of the Brockhaus encyclopedia from 2005/2006 were sold, as FOCUS reported. According to the FAZ , the break-even point was 20,000 copies sold, half of which were reached. This last printed edition of the Brockhaus Encyclopedia consisted of thirty cloth-bound volumes with gilt edges, containing almost 25,000 pages. It cost 2670 euros.

illustrations

Hardly any illustrations have survived from the ancient works, just the text. They later received illustrations in some medieval manuscripts. These illustrations mostly differed from manuscript to manuscript; Then the printing press made it possible to reproduce images precisely. The Middle Ages already knew pictures of people, animals or plants, as well as schematic representations and world maps. However, they were rare.

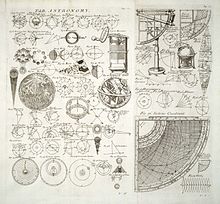

In the early modern period there was a wide range of different illustrations. Title pages and frontispieces reflected on the basics of the knowledge collected in the encyclopedia by allegorically depicting the seven liberal arts. Tree diagrams illustrated the connection between the individual subjects, functional diagrams showed, for example, how a pulley system works. Dedications presented a wealthy patron or patron, copper engravings introduced a new volume. Tables, for example for planetary motions, were also popular.

Pictures were either inserted at the appropriate place in the text or provided on separate picture plates; 1844-1849 and even later, the Brockhaus-Verlag brought out a picture atlas for the conversation lexicon and called it the iconographic encyclopedia of sciences and arts in the subtitle . Illustrated panels or even illustrated books were often printed separately from the rest because of the quality, since images sometimes required special printing or special paper. As printing technology improved, more and more images entered encyclopedias. After all, richly illustrated works were no longer explicitly advertised as “illustrated” in the 20th century, as illustration had become so taken for granted. From about the late 1960s, some encyclopedias had illustrations in full color.

The 19th edition of the Brockhaus (1986–1994) had 24 volumes with a total of 17,000 pages. It contained 35,000 illustrations, maps and tables. An associated world atlas contained 243 map pages.

attachments and equipment

Since the 18th century, larger encyclopedias have received supplementary volumes, supplements , if no new edition has been published . In the middle of the 19th century, the Brockhaus published yearbooks as a supplement or continuation of the actual encyclopedia. From 1907 Larousse published the monthly journal Larousse mensuel illustré . The magazine Der Brockhaus-Greif , which the publishing house maintained from 1954 to 1975, served more for customer loyalty . A special volume could be used to deal with special historical events, such as the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871 or the First World War.

Appendices in separate volumes could also be illustrated books, atlases, or dictionaries, making the encyclopedia an all the more complete compendium. Finally, CD-ROMs, Internet access and USB sticks were initially offered as extras for the printed version. The artists' editions of the Brockhaus represented an attempt to increase the value of the entire work, such as the edition designed by Friedensreich Hundertwasser since 1986 and limited to 1800 copies. The retail price was 14,000 DM (compared to about 4000 DM for the normal edition). The covers, standing next to each other on the shelf, showed a new picture together.

delivery

As a rule, books were purchased and paid for after completion. For larger projects, however, it was customary in the 18th century to first recruit subscribers and only then print the work; it may have been delivered piecemeal in installments. If the buyer had all the deliveries together, he could take them to a bookbinder. A subscriber (literally: someone who signs) paid in advance. So the publisher already had capital with which he could cope with the first expenses. Depending on the subscription model, the subscriber might pay a deposit and then another per part shipped. In addition, the publisher hoped that other customers would buy the work. The publication of well-known subscribers at the front of the work should have a sales-promoting effect, similar to dedicating the work to a person of high rank.