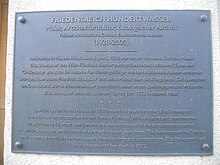

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Friedensreich Hundertwasser Regentag Dunkelbunt (civil: Friedrich Stowasser , born December 15, 1928 in Vienna ; † February 19, 2000 on board the Queen Elizabeth 2 off Brisbane ) was an Austrian artist who primarily worked as a painter , but also in the fields of architecture and environmental protection was active. He formed his stage name Hundertwasser in 1949 from his real name by seemingly Germanizing the first syllable - sto is the word for "hundred" in Slavic languages .

He appeared all his life as an opponent of the "straight line" and any standardization, which is particularly important in his work in the field of building design, which is characterized by imaginative liveliness and individuality , but above all by the inclusion of nature in the architecture.

Life

Hundertwasser was the only child of the unemployed engineer Ernst Stowasser and his wife Elsa. The families on the father's side come from Bohemia and on the mother's side from Moravia . Thirteen days after his first birthday, his father died of appendicitis , so his mother raised him alone. At the age of seven he came to the Montessori school in Vienna. The local art educators attested him “an extraordinary sense of shape and color”. Although his mother was Jewish , Hundertwasser was baptized a Catholic in 1935 . After the annexation of Austria , he was accepted into the Hitler Youth at the age of ten . Since private students were more noticeable to the outside world, Elsa Stowasser had her son transferred to a public school in Vienna.

He and his mother were forcibly relocated by the National Socialists to the house at Obere Donaustraße 12 in Vienna II ( Leopoldstadt ). In contrast to his grandmother and a total of 69 other relatives, the two survived the National Socialist terror.

After graduating from the Bundesrealgymnasium Wien XX, Unterbergergasse, in 1948, he attended the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts for three months in the winter semester 1948/49 . There he began to sign his works with the artist name Hundertwasser . Shortly after dropping out of his studies, Hundertwasser traveled to Italy for the first time in April 1949 . There he met the French artist René Brô . They traveled together to Paris in 1950 . Hundertwasser also traveled to Morocco (first half of 1951), Tunisia and Sicily . The impressions of the trip to North Africa were particularly decisive for his painting, as was the encounter with the works of Egon Schiele , Paul Klee and Walter Kampmann . In the watercolors created in Italy in 1949, Kampmann's “crystal-clinking, transparent trees of the soul” appear, and they already hint at the significance that the tree, the vegetation, and “nature with a soul” will assume in Hundertwasser's work and in his thinking.

The loner Hundertwasser traveled a lot during his life and learned English, French and Italian. He also spoke a little Japanese, Russian, Czech and Arabic. He always had a miniature paint box with him so that he could paint anywhere and immediately.

Hundertwasser had his first exhibitions in 1952 and 1953 in his hometown of Vienna, in 1955 in Milan and in 1954 and 1956 in the Facchetti Gallery in Paris.

Hundertwasser lived in Paris in the 1950s. He dealt with the ruling avant-garde as an active participant in the current discourse between geometric and expressive abstraction, Informel and burgeoning Nouveau Réalisme . The most important personal contacts included Michel Tapié and Yves Klein as well as the critics Pierre Restany and Julien Alvard . As a reaction to the Tachism of the École de Paris with its automatistic-gestural, random-controlled way of working, he formulated his own view, the transautomatism, which is not only about a new emergence of art, but also about a new perception, the calls for an active, responsible and creative viewer.

In 1957 Hundertwasser bought a farm on the edge of Normandy . In 1958 he married 16-year-old Herta Leitner in Gibraltar . The marriage was divorced two years later.

In 1959 he was appointed guest lecturer at the Hamburg University of Fine Arts . In December of that year he drew the Infinite Line with Bazon Brock and Herbert Schuldt as well as with students in his classroom , an "exemplary project of the actionist avant-garde". Hundertwasser resigned his lectureship after the university director had forced the line to be broken off.

In 1961 Hundertwasser traveled to Japan , where he received the Mainichi Prize at the 6th International Art Exhibition in Tokyo. In 1962 he married a second time. The marriage with the Japanese Yuko Ikewada was divorced in 1966. During the time in Japan, the name Friedensreich was also created . He translated his first name into the Japanese characters for the terms peace and rich and called himself from now on Friedereich, from 1968 on Friedenreich and finally in the final form Friedensreich.

In 1962 Hundertwasser had great success with a retrospective at the Venice Biennale in the Austrian pavilion, set up by Vinzenz Oberhammer . Two years later, the Kestner Society in Hanover showed an extensive retrospective, organized by Wieland Schmied , which was also presented as a traveling exhibition in Amsterdam, Bern, Hagen, Stockholm and Vienna. In addition, the Kestner Society published the artist's first oeuvre catalog, edited by Wieland Schmied.

After the farmhouse in Normandy, Hundertwasser bought the “Hahnsäge”, which was no longer in use, in the sparsely populated Lower Austrian Waldviertel in 1966 . There, far from the hustle and bustle and in the midst of nature, he set up his home. In 1964 his works were shown in the painting department at documenta III in Kassel .

In 1968 Hundertwasser travels to California to prepare a museum exhibition with catalog with Herschel Chipp at the University of California at Berkeley, which then traveled through cities in the USA (Santa Barbara, Houston, Chicago, New York, Washington DC) until 1969.

From 1970 to 1972 he worked with the director Peter Schamoni on the film Hundertwasser's Regentag . This was the second film about the artist's life after the documentary “Hundertwasser” by Ferry Radax (1966). It is about the old salt freighter with which Hundertwasser sailed from Sicily to Venice in 1968 and which, after being completely converted into Hundertwasser's ship, became rainy day .

In 1972 Hundertwasser founded Gruener Janura AG in Switzerland , which was renamed Namida AG in 2008. Hundertwasser managed its copyrights through this stock corporation .

Following a touring museum exhibition in New Zealand and Australia, on the occasion of which Hundertwasser first traveled to New Zealand in 1973, he acquired several properties in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand that cover the entire Kaurinui Valley with a total area of around 372 hectares. He realized his dream of giving his land back to nature and helping nature to gain its rights. He planted more than 100,000 native trees, built canals and ponds, and herbal sewage treatment plants . He used solar and water energy by means of solar panels and a water wheel . As in all of his residences, he also used the humus toilet there. An old farmhouse, the "Bottlehouse" designed by him, as well as "Pigsty" and "Mountain hut" served him as living and working space.

In 1975 Hundertwasser took part in the Triennale di Milano, where he had around 15 “tree tenants” planted through windows in Via Manzoni and published the manifesto “Inquilino Albero” (tree tenants). With his tree tenant campaigns (Vienna, 1981, Munich 1983), Hundertwasser became a pioneer of facade greening ( vertical garden ).

In 1979 Hundertwasser acquired the " Giardino Eden ", a 15,000 square meter garden with a palazzo, through his Swiss company in Venice .

Hundertwasser designed a poster for the artist series for the XX. 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich and began to design postage stamps in 1975 . In 1982 he designed the facade of the Rosenthal factory in Selb . One year later, the foundation stone was laid for the Hundertwasser House in Vienna, which was handed over to the tenants on February 17, 1986. In the following years, Hundertwasser worked on numerous architecture projects in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, California, Japan and New Zealand.

In 1981 he was appointed head of a master school for painting at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna .

In 1982 Hundertwasser's only child, his daughter Heidi Trimmel, was born.

In 1984 he took an active part in the occupation of the Hainburger Au to prevent the construction of a power plant and demonstrated with activists in freezing temperatures. At a press conference in the Concordia press club, he tore up the Grand Austrian State Prize that had been awarded to him in front of the camera .

When the Austrian National Council decided in 1988 to introduce new license plates with a white background and black letters and numbers, Hundertwasser campaigned for the retention of the black Austrian license plates with white numbers with a large number of public appearances, circulars and petitions. He wanted to preserve Austria's national and regional identity. He designed license plates with white letters and numbers on a black background and initiated a collection of signatures for a referendum to keep the black license plates. Although there was a majority in parliament for the amendment of the number plate law, the white EU-compliant license plates were enforced on January 1, 1990.

He has also spoken out against Austria's accession to the EU since 1988 in appeals, writings and pamphlets in many different media. He feared the destruction of the regional independence and saw the EU as a commercial agency for big business, big banks, “poison companies” and “monoculture monopolists”, the nuclear and gene lobby.

The KunstHausWien Museum Hundertwasser was opened on April 9, 1991. It houses the world's only permanent Hundertwasser exhibition, which offers insights into all of the artist's creative areas (youth work, painting, original graphics, tapestry, applied art and architecture). International temporary exhibitions are shown on two additional floors.

In 1993 he was won over to the idea of creating an artistically interesting design for the Latin-German school dictionary Der kleine Stowasser by Joseph Maria Stowasser on the occasion of a planned new edition, "a gift for young people" ( source: formulation of the publisher ). This anniversary edition of the dictionary, which is widespread throughout the German-speaking region, appeared in 1994 in exactly one hundred (cf. “Sto” - “Hundred”) different color variations and is still available today. In 1995 the "Hundertwasser Bible" appeared. The 1688-page Bible is illustrated with thirty collages and fifty works of art created especially for this edition . The bindings are handmade and each unique .

In the late 1990s, Hundertwasser was mainly concerned with architectural projects in Germany, Japan and New Zealand.

In 1999 he began to write comments on many of his works for a catalog raisonné, which was published by Taschen Verlag after his death. He designed the layout and cover design of the two-volume catalog and determined the sizes of the reproductions of his works. He had already started numbering his works in 1954. His works were recorded, described, listed and documented in detail in his archive. There are no works that are not documented in the Hundertwasser Archive in Vienna.

On February 19, 2000, Friedensreich Hundertwasser died of heart failure on board the Queen Elizabeth 2 on the return journey from New Zealand to Europe . According to his last wish, he was buried on his property in New Zealand on March 3, 2000, without a coffin and naked, wrapped in a Koru flag designed by him . A tulip tree was planted on his grave .

According to his manager Joram Harel, Hundertwasser had no assets and his estate was over-indebted due to his lavish lifestyle. On the other hand, friends of Hundertwasser say that he lived extremely modestly and did not even spend money on cutting his hair.

Art creation: painting - graphics - tapestry

painting

Hundertwasser began traveling in 1949 and his stays in Italy, France and North Africa influenced his artistic development. Hundertwasser became a painter while traveling and through encounters with works by Egon Schiele, Paul Klee and Walter Kampmann. In the watercolors created in Italy in 1949, the "crystal-clinking, transparent trees of the soul" appear, which he incorporates into his pictorial world under the impression of the works of the painter Walter Kampmann, who is now almost forgotten and in which the meaning of the tree, the vegetation, the "ensouled" nature will occupy in his work and in his thinking. The impressions that Hundertwasser gained on the trip to Morocco and Tunis in 1951 were particularly decisive for his painting. In 1953 he used the spiral for the first time, which became the defining element of his painterly work. Hundertwasser described his painting as "vegetative".

“A major part of the effect of Hundertwasser's painting comes from the color. Hundertwasser instinctively uses the color without assigning certain colors to certain characters according to any rules, including self-determined ones. He prefers intense, bright colors and loves to place complementary colors right next to each other - for example to point out the double movement of the spiral. [...] The position of his painting today is singular and without parallel. "

Heimann-Jelinek believes that Hundertwasser's labyrinthine spiral style has its roots in the constant tension and fear that he had to experience between 1938 and 1945. Hundertwasser deliberately dealt with the Shoah for some time , as evidenced by images such as Blood rains on houses (1961 ), Jews ' house in Austria (1961–62), Blutgarten (1962) or the crematorium (1963). Hundertwasser worked in many graphic techniques: lithography, screen printing, etching, color woodcut and others. He was the first European painter whose works were cut and printed by Japanese masters. Above all, he succeeded in producing graphic editions whose sheets are unique .

graphic

From the 1970s, Hundertwasser deepened his work in printmaking. In collaboration with the printers, he developed complex processes with a large number of color separations, used phosphorescent or fluorescent colors, experimented with reflective glass dust coatings or electrostatic flocking, and led his graphics to increased luminosity and attractive surface effects. In the mere multiplication of a graphic work, he saw the sterility of the straight line he was fighting against, which is why many of his graphic editions consist of different color compositions and variations. With the 10,002 sheets of the graphic 10.002 Nights Homo Humus Come Va How do you do , published in 1984, he succeeded in producing as many different sheets as the number of copies.

Hundertwasser worked in various printing techniques and his relatively small graphic work consists of 11 Rotaprint lithographs, 13 lithographs, 33 serigraphs, 40 Japanese woodblock prints, 19 etchings, 7 mixed media prints and 1 linocut. Walter Koschatzky , former director of the Albertina graphic collection (Vienna) , arranged the graphics chronologically according to the date of publication in the catalog of graphic works he published in 1986 and introduced consecutive HWG numbers (Hundertwasser graphic numbers). With the continuation of the graphic work after 1986, Hundertwasser's graphic work had 124 HWG numbers.

Hundertwasser has combined part of his Grapfian oeuvre in portfolios, the earliest being the Art Club Rotaprint Portfolio (zinc lithographs printed with Rotaprint machine) from 1951, two portfolios with screen printing (Look at it on a rainy day, 1972 and La Giudecca Colorata, 2001), as well as three portfolios with Japanese woodblock prints (Nany Hyaku Mizu, 1973; Midori No Namida, 1975; Joy of Man, 1988). Hundertwasser also designed the wooden boxes for storage for the screen printing and woodcut portfolios, with the rainy day folder (Look at it on a rainy day) being a special feature because it is handwritten numbered and signed by the artist.

Hundertwasser was the first European painter whose works were cut and printed by Japanese masters. They had to face the challenge of transferring the richness of colors of Hundertwasser's works into the required oversized number of often more than twenty wooden pull-out panels. Hundertwasser was convinced that the only correct way in the art of original graphics was a collaboration between artist, technician and printer, with the artist having the superordinate, directing function and also intervening in the technical process and taking responsibility.

At the end of the 1960s, Hundertwasser began to work with screen printing. A sophisticated reproduction technique as well as manual reworking made it possible to achieve a variety of new expressive possibilities and image effects. Already in the first serigraphs he used metal foil embossing and fluorescent colors. The Italian studio Quattro printed 10,000 copies of the graphic 686 Good Morning City and 686 Good Morning City - Bleeding Town in a total of 50 color variants of 200 pieces each. The ten screen prints in the Look at it on a rainy day portfolio , printed by Dietz Offizin in Lengmoos, were created using a complicated printing process with a large number of color separations. For the first time, phosphorescent colors or reflective glass dust covers were used. In the graphic 700 Olympic Games Munich 1972 an electrostatic flocking was applied. Hundertwasser printed his graphics in gravure printing (etching) from 1974 in Vienna, when the opportunity arose to work with the printers Robert Finger and Wolfgang Raab. Hundertwasser also opted for difficult and effective printing processes for etching, for example when iridescent gradients were created using aquatint plates, which in turn were printed over colored paper collages (chine-collé). With printer Claudio Barbato in Venice, Hundertwasser finally found a congenial partner for mixed media combination prints in which lithography, screen printing and embossing (metal foil embossing) were used.

Hundertwasser was always careful to provide precise work information on the graphic sheets himself in order to achieve the most complete disclosure of the techniques and dates of the work's creation. Hundertwasser's signature (handwritten and in the form of Japanese Incans ), numbering (copy number / edition size ), date and place of the signature, œuvre number, in many cases the name of the work, mentions or stamps and embossing of publishers can be found on the graphics , Printers, paper and paint manufacturers or the coordinators deployed as well as color separation points. Lists of color variants, technical versions and print runs can be found on many graphics, embossed, stamped or printed.

tapestry

Hundertwasser's first tapestry, 133 Pissing Boy with Skyscraper , was created in 1952 on the basis of a bet with Fritz Riedl, in which Hundertwasser had claimed that tapestries could also be woven without cardboard, i.e. without a template the size of the tapestry. After six long months in which Hundertwasser worked “with hands and feet” on the loom, the tapestry was ready and Hundertwasser had won the bet. All subsequent tapestries were also made without cardboard, but they were made by weavers selected by Hundertwasser. When translating his works into a tapestry, Hundertwasser was concerned with the free implementation of one of his works in another medium and with the artistic interpretation by the weavers, that is, implementation without a template or cardboard. In Hundertwasser's view, only this procedure without cardboard could breathe life into the work, only in this way could a real artistic work be created and not an inanimate copy of the original. For this reason, all Hundertwasser tapestries are unique. Hundertwasser only cooperated with a few weavers. Almost all of his tapestries were created in collaboration with Hilde Absalon in Vienna and Fritz Riedl or his studio in Mexico.

architecture

“Today we live in a chaos of straight lines, in a jungle of straight lines. If you don't believe this, take the trouble to count the straight lines that surround you and you will understand; because he will never get to the end. "

Since the early 1950s, Hundertwasser has dealt with architecture and advocated architecture that is more natural and more human. He began his engagement with manifestos, essays and demonstrations such as the “Moldy Manifesto against Rationalism in Architecture” (1958). In the “ Mold Manifesto ” he formulated the rejection of rationalism, straight lines and functional architecture. He postulates the "window right" as the right of every individual to bend out of his window and - as far as his arms reach - to paint the masonry. In his "naked speech for the right to a third skin" in Munich in 1967 as part of an action by the Pintorarium, a universal academy of all creative directions, founded by Hundertwasser, Arnulf Rainer and Ernst Fuchs , Hundertwasser castigated the enslavement of people by the sterile grid system of Architecture and through the series production of a mechanized industry. His second naked speech and the reading of the architecture boycott manifesto “Los von Loos - Law for Individual Building Changes or Architecture Boycott Manifesto” took place in Vienna in 1968.

In his architecture boycott manifesto he refers to the rational, sterile architecture that emerged in the tradition of the Austrian architect Adolf Loos ("Ornament und Verbrechen"), which for him, in its deadly monotony, is responsible for the misery of the people. He calls for a boycott of this architecture, demands creative freedom of construction and the right to individual construction changes. In this context he coined the terms “window right” and “tree obligation” (1972).

Hundertwasser had his first architectural models made in the 1970s, for example the models for the Eurovision program Wünsch Dir was , with which he illustrated his ideas for roof forest, tree tenants and window rights. In these models he created architectural forms such as the Augenschlitzhaus, the terrace house and the Hoch-Wiesen-Haus, later the models pit house, spiral house, the green gas station and the "invisible and inaudible motorway" were added. Since the early 1980s, Hundertwasser worked as an "architecture doctor", as he called himself. His actual work in the field of architecture began with the construction of the residential complex of the municipality of Vienna (architects Krawina and Pelikan) in Löwengasse. The house immediately became a tourist magnet. Hundertwasser's numerous follow-up projects in Europe and overseas (in collaboration with the architects Springmann and Pelikan) were generally received with great approval by the general public, but mostly vehemently rejected by architects and specialist critics. This confrontation was particularly sharp around the mid-1990s.

Ecological commitment

Closely linked to Hundertwasser's philosophy of architecture in harmony with nature was his ecological commitment. He campaigned for the preservation of the natural habitat of people and demanded a life in harmony with the laws of nature. He wrote numerous manifestos , gave lectures and designed posters in favor of nature conservation, against nuclear energy, to save the seas and whales and to protect the rainforest.

He was an advocate of the humus toilet and the principle of the plant-based sewage treatment system . For him, feces were not nauseating, but part of the cycle of nature. His manifesto The Holy Shit and instructions on how to build a composting toilet testify to this .

Political opinions

As a result of his experience as a person persecuted by the Nazi regime, Hundertwasser took a consistently anti- totalitarian position early on . It should by his mother in the sense of the traditions of the interwar period kuk -Nostalgie have been affected. His early fears of the dictatorship battalions marching in the square may have contributed to his rejection of the geometrization of man and his architecture . In a letter from 1954, Hundertwasser associates the rectangle with "the columns of marches pressed into geometric rectangles".

In 1959, on the occasion of the Dalai Lama's escape from Tibet , Hundertwasser got involved in Carl Laszlo's magazine "Panderma" for the Tibetan religious leader. In later years, as a well-known artist, Friedensreich Hundertwasser was active as an environmental activist and most recently made a name for himself as an opponent of the EU and an advocate of the preservation of regional idiosyncrasies. One of the lesser-known facets of Hundertwasser's personality is his commitment to the constitutional monarchy :

“Austria needs a superordinate center, consisting of everlasting higher values - which one no longer dares to express - such as beauty, culture, inner and outer peace, faith, wealth of the heart [...]

Austria needs an emperor who is subject to the people is. A superordinate and radiant greatness in which everyone has confidence, because this greatness is in everyone's possession. The rationalist way of thinking has brought us an ephemeral (= short-lived; editor's note) higher standard of living at the expense of nature and creation , which is now coming to an end, but our heart, our quality of life , our longings destroyed, without which an Austrian cannot live.

It is monstrous that Austria should have an emperor who did no harm to anyone and still treated him like a leper. Austria needs a crown! Long live Austria! Long live the constitutional monarchy ! Long live Otto von Habsburg ! "

Works

Hundertwasser created many objects of applied art, designed postage stamps, flags, coins, books and porcelain objects. He designed the “Vindobona”, a passenger ship of the DDSG Blue Danube (1995), and a Boeing B 757 for the Condor airline, Germany (not realized).

Buildings

Hundertwasser House in Vienna

The hill meadow country Rogner Bad Blumau in Styria (Austria)

Parish Church Bärnbach " Hundertwasser Church "

Hundertwasser House Living Beneath the Rain Tower Plochingen

Small onion dome in front of the Waldspirale , Darmstadt

Spittelau waste incineration plant , Vienna

Markthalle Altenrhein (Switzerland)

Austria fountain in Zell am See

Hundertwasser's last project: Green Citadel , Magdeburg

Residential house at the Quellenpark in Bad Soden am Taunus

The “ Hundertwasser toilets ” in Kawakawa ( New Zealand ) - Hundertwasser's last structure, the only one in the southern hemisphere

Hundertwasser designed the following structures, many of them in collaboration with the architects Peter Pelikan and Heinz M. Springmann :

- Austria

- Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna , 1983–1985 (original co-author Josef Krawina )

- The hill meadow country Rogner Bad Blumau , Bad Blumau Styria , 1993–1997

- Mierka Grain Silo Krems , 1982–1983

- Rupertinum Salzburg ( tongue beard ), 1980–1987

- St. Barbara Church in Bärnbach , 1987–1988 (architect Manfred Fuchsbichler)

- Roiten Village Museum , 1987–1988

- Rueff textile factory in Muntlix and house numbers in Zwischenwasser , 1988

- Spittelau waste incineration plant , 1988–1997

- Bad Fischau motorway service station , 1989–1990

- KunstHausWien , 1989–1991

- Kalke Village, Vienna, 1990–1991

- Zwettl fountain , 1992–1994

- Pavilion at the DDSG Blue Danube Ponton Vienna, 1992–1994

- Spiralfluss Drinking Fountain I Linz , 1993–1994

- Infirmary (oncology) Graz , 1993–1994

- Austria Fountain in Zell am See , 1996–2003

- Passenger ship Vindobona , DDSG , put into service in 1979, now "Hundertwasserschiff"

- Germany

- Rosenthal factory in Selb , 1980–1982

- Hundertwasser day care center in Frankfurt-Heddernheim , 1988–1995

- Öko-Haus Hamm , Maximilianpark, 1981–1982

- In the meadows of Bad Soden am Taunus , 1990–1993

- Living under the Plochingen am Neckar rain tower , 1991–1994

- Luther-Melanchthon-Gymnasium in Lutherstadt Wittenberg , 1997–1999

- The Stadtcafé Ottensen in collaboration with Jule Beck, 1998

- The Forest Spiral of Darmstadt , 1998-2000

- Uelzen train station , 1999–2001

- Dome at the Düsseler Tor kindergarten in Wülfrath , 2001

- Green Citadel of Magdeburg , 2004–2005; the last building designed by Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

- Ronald McDonald House of McDonald's Children's Aid in Essen / Grugapark

- Kuchlbauer tower in Abensberg (after the rejection of the original design by the monument protection, a smaller redesign was realized by the architect Peter Pelikan )

-

United States

- Quixote Winery Napa Valley , 1992-1999

-

Switzerland

- Altenrhein market hall , 1998–2001

-

New Zealand

- Hundertwasser toilet , a public toilet in Kawakawa , 1999

photos

Hundertwasser's pictures are painted in watercolor or mixed media, a few as oil paintings. He made many of his colors himself and painted with water colors, with oil paints and egg tempera, with glossy lacquers and ground earth. He usually made the "chassis" of his paintings himself and almost always put up the canvases himself. He painted on a wide variety of papers, in his early years preferring used packing paper, and mounted them on picture carriers such as fibreboard or canvas.

Hundertwasser created fewer than 1000 pictures, although the catalog raisonné published by Taschen Verlag 2002 does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the exact number, because its systematics and numbering follow the artist's specifications. Hundertwasser numbered his works himself. He saw the oeuvre number as part of the name of a work and always framed it in an oval. Numbers 1 to 1008 of the main work not only contain mixed media pictures and watercolors, but also drawings and other works such as graphics that Hundertwasser has given a number. In addition, there are series of drawings (Doodle drawings) under the main work numbers, which are grouped under a single number. Youth works (works 1934–1949) are numbered separately. An online catalog raisonné created by the Hundertwasser Archive in Vienna has existed at www.hundertwasser.com since 2008.

| 433 That I don't know yet |

|---|

| Friedensreich Hundertwasser , 1960 |

| Mixed media |

| KunsthausWien, Vienna

Link to the picture |

- 1952: 147 The Match of the Century , private collection

- 1955: 224 The Great Way , Belvedere , Vienna

- 1959: 425 Kaaba penis - Half the island , Hamburg Poppe Collection

- 1960: 433 I don't know yet , KunstHausWien

- 1971: 699 The houses hang at the bottom of the meadows

- 1988: 897 Silver Spiral , KunstHausWien

In 1954 Hundertwasser developed the art theory of transautomatism .

Postage stamps

Hundertwasser's extensive oeuvre includes 26 works that he himself conceived as postage stamp designs for various postal administrations. Seventeen of these designs were implemented as postage stamps, some of them after his death.

- Austria

- Modern art in Austria, 1975

- Summit conference of the heads of state and government of the Council of Europe member states, Vienna, 1993

- 80th birthday of Friedensreich Hundertwasser (4 stamps in the form of a block), 2008

- Senegal - Art on Postage Stamps (3 stamps), 1979

- Cape Verde Islands - Shipping, 1982 (printed but not issued), 1985 (issued with overprint)

- UN Postal Administration (Vienna, Geneva and New York ) - 35th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (6 stamps), 1983

- Liechtenstein - Homage to Liechtenstein, 1993

Two of the drafts were not carried out because they were alternative drafts to a stamp issue (United Nations, Senegal). Seven other designs were created for the postal administrations of Morocco and French Polynesia and were not realized as postage stamps. In addition, Friedensreich Hundertwasser adapted some of his works for postage stamp issues. On the basis of these adaptations, stamp editions were made by:

- France - 2 badges for the Council of Europe , 1994

- UN Postal Administration (Vienna, Geneva and New York) - Social Summit (3 stamps), 1995

- Luxembourg - European Capital of Culture (3 stamps), 1995

- Liechtenstein - EXPO 2000 Hanover (3 stamps), 2000

The Austrian Post used other Hundertwasser motifs for the 1987 European edition ( Modern Architecture , Hundertwasserhaus), on the occasion of his death in 2000 (Blue Blues painting, as part of WIPA 2000) and 2004 Donauauen National Park (poster The free nature is our freedom on the occasion of the Anniversary of the occupation in Hainburg ).

For the first time, a Hundertwasser motif was reproduced on a Cuban postage stamp on the occasion of the Salon de Mayo art exhibition (Havana, 1967). With the exception of the official stamps for the Council of Europe and the Cuban stamp, all stamps were engraved by Wolfgang Seidel and produced by the Austrian State Printing House using an elaborate combination printing process ( intaglio printing , halftone gravure printing, some with metal embossing).

Book designs and other examples of applied arts

- Brockhaus Encyclopedia : In 1989 the 19th edition of the 24-volume Brockhaus Encyclopedia designed by Hundertwasser was published in a special edition limited to 1,800 copies. Each cover of this edition varies in the color of the linen as well as in the colors of the foil stamping, so each copy is unique . “No volume, no cover of the encyclopedia I designed is the same as another. Nevertheless, despite all the differences, they interlock and form an overall picture. This networking with one another is a symbol of the knowledge that Brockhaus imparts ”. (F. Hundertwasser).

- Stowasser : Latin-German school dictionary by Joseph Maria Stowasser . For the 1994 edition of the dictionary “Der kleine Stowasser”, Hundertwasser designed textile covers in 100 different color variations.

- Bible 1995, format: 20 × 28.5 cm, 1,688 pages, 80 full-page images, 30 of which are collages that Hundertwasser created especially for this Bible edition . Each Bible is characterized by a different color combination in the linen weave. The specimens also differ in the shiny, shiny metal color embossing. Each binding was mostly made by hand.

- Hundertwasser Furoshiki , Hundertwasser's contribution to a waste-free society, a Japanese wrapping cloth, an impetus for a new packaging culture.

Awards

- 1959: Sanbra Prize at the 5th São Paulo Biennale

- 1961: Mainichi Prize in Tokyo

- 1980: Grand Austrian State Prize for Fine Arts

- 1981: Austrian Nature Conservation Prize

- 1985: Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- 1988: Medal of Honor of the Federal Capital Vienna

- 1988: Gold Medal of Honor of the State of Styria

- 1997: Great Decoration of Honor for Services to the Republic of Austria [37]

- 1998: Columbus Prize of Honor from the Association of German Travel Journalists

Honors

The following streets and squares were named after Hundertwasser:

- Hundertwasser-Promenade, Vienna, Landstrasse (3rd district); 2002

- Friedenreich-Hundertwasser-Platz, Vienna, Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus (15th district); 2007

- Hundertwasser Platz, Uelzen, Germany

- Hundertwasser Allee, Salzburg; 2001

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser Park, Wittenberg, Germany

- Hundertwasser Street, Wuelfrath, Germany

- Rue Friedrich Stowasser, Saint-Jean-de-la-Forêt , France

The following schools in Germany were named after Hundertwasser:

- Hundertwasser Comprehensive School Rostock

- Hundertwasser School Gütersloh

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser School Neukirchen-Vluyn

- GGS Hundertwasserschule Duisburg

- Hundertwasser Elementary School Leeste

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser School in Würzburg

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser School in Münster

In 2004 the Austrian composer Roland Baumgartner created a multimedia musical about Hundertwasser; Music Konstantin Wecker

Movies

- Ferry Radax : Hundertwasser - Experimental Film Portrait (1966)

- Peter Schamoni : Hundertwasser's Rainy Day (Documentation, 1972)

- Hundertwasser in New Zealand - Island of Lost Desire, produced for Living Treasures by Telecom, directed by Brian Lennane, copyright 1990 TV NZ

- Ferry Radax: Hundertwasser - Life in Spirals (Documentation, 1995–1998)

The Hundertwasser non-profit private foundation

The Hundertwasser non-profit private foundation was established in April 1998 and is the testamentary heir to Friedensreich Hundertwasser. Its purpose is to preserve and continue the work of the late founder and artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser. Via its subsidiary Namida AG (Glarus, Switzerland), it owns the copyrights to the works of the late artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser. The Hundertwasser Gemeinnützige Privatstiftung is entitled to exercise the moral rights of Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, his manager Joram Harel and Harel's tax advisor Johannes Strohmayer became the board of directors of the foundation . After Hundertwasser's death, Harel's daughter Tanya Harel was co-opted to replace Hundertwasser's board of directors. In 1998, Karl Hengstberger, an employee of the auditing and tax consultancy firm Hübner & Hübner, in which Johannes Strohmayer holds a 26% stake, was appointed as the foundation auditor for ten years.

Kawakawa Hundertwasser Park Charitable Trust

Friedensreich Hundertwasser's death in February 2000 brought together a group of committed citizens who jointly founded the Kawakawa Hundertwasser Park Charitable Trust . His goal is to preserve the memories of Hundertwasser's life in his adopted home New Zealand, so that future generations can learn from his ecological thoughts 'hoatu ki te tangata' (for the people) that he realized here and about his deep connection to the people of Kawakawa. Hundertwasser Park is being built behind the trust-guarded toilets that Hundertwasser helped build . The area was blessed in 2013 and the first trees were planted.

literature

Catalog raisonnés

- Hundertwasser, complete oeuvre catalog published on the occasion of the 100th exhibition of the Kestner Society, Hanover 1964

- David Kung: The Woodcut Works of Hundertwasser. Gruener Janura, Glarus 1977.

- Walter Koschatzky : Friedensreich Hundertwasser. The complete graphic work 1951–1986. Office du Livre, Friborg, Orell Füssli Verlag, Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-280-01647-9 .

- Hundertwasser 1928-2000. Catalog raisonné. Volume 1: Wieland Schmied: Personality, Life, Work . Volume 2: Andrea Fürst: Catalog raisonné . Cologne: Taschen, Cologne 2000/2002, ISBN 3-8228-6014-X .

- Hundertwasser Graphic Works 1994-2000. Museums Betriebsgesellschaft, Vienna 2001.

- Andrea Christa Fürst: The unknown Hundertwasser. Prestel, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7913-4120-0 .

Monographs

- Hundertwasser. With a foreword by Wieland Schmied and explanations of the pictures by the painter himself. Buchheim Verlag, Feldafing 1964.

- Werner Hofmann: Hundertwasser. Verlag Galerie Welz, Salzburg 1965.

- Francois Mathey: Hundertwasser. Südwest Verlag, Munich 1985.

- Harry Rand: Hundertwasser, the painter. Bruckmann, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-7654-2075-1 .

- Harry Rand: Hundertwasser. Taschen, Cologne 1991.

- Pierre Restany: The power of art. Hundertwasser. The painter-king with the five skins. Taschen, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-8228-7856-1 .

- Pierre Restany: Hundertwasser. Parkstone, New York 2008.

- Georgia Illetschko: Planet Hundertwasser. Prestel, Munich 2012.

Architecture monographs

- Robert Schediwy : Hundertwasser's houses. Documents of a controversy about contemporary architecture. Edition Tusch, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-85063-215-6 .

- Hundertwasser Architecture - For building that is more natural and human. With a foreword by Wieland Schmied. Taschen, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-8228-8594-0 .

- Rosemarie Banholzer, Peter Mosdzen, Friedensreich Hundertwasser: Impressions. Concept & design, Verlag Michael Wegmann, Konstanz 2016, ISBN 978-3-9817535-0-9 . (Architecture projects: Friedensreich Hundertwasser, photographs: Peter Mosdzen, poems in German: Rosemarie Banholzer).

Exhibition catalogs

- Hundertwasser is a gift for Germany. Catalog for the exhibition in the Änne Abels gallery, Cologne 1963

- Hundertwasser, complete oeuvre catalog. Published on the occasion of the 100th exhibition of the Kestner Society since its reopening after the war. Kestner Society, Hanover 1964

- Herschel B. Chipp, Brenda Richardson (Eds.): Hundertwasser. Catalog for the exhibition at the University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley 1968

- Hundertwasser. Catalog for the exhibition at Aberbach Fine Art, New York 1973 (designed by Hundertwasser.)

- Hundertwasser 1973 New Zealand. Published on the occasion of the traveling exhibition of Hundertwasser's graphic works in New Zealand and Australia 1973/1974 (designed by Hundertwasser)

- Friedrich Stowasser 1943–1949, catalog for the exhibition Graphic Collection Albertina, Vienna 1974

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser rainy day. Catalog for the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst, Munich 1975 (designed by Hundertwasser)

- Austria shows the continents Hundertwasser. (English, French, German editions, 1975–1983, additional books in various languages).

- Hundertwasser Is Painting. Catalog for the traveling exhibition 1979–1981, Gruener Janura, Glarus 1979.

- Hundertwasser. Hundertwasser Exhibition 1989, Japan Tour. ed. by Joshiharu Sasaki, Yuriko Ishikawa, Iwaki City Art Museum; Tomoko Oyagi, Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Museum; Hitoshi Morita, Ohara Museum of Art.

- Hundertwasser. Important Works. Exhibition at Landau Fine Art, Montreal 1994.

- Hundertwasser. APT International, Tokyo 1998.

- Klaus Wolbert (Ed.): Hundertwasser retrospective 1948–1997. Catalog for the exhibition at the Mathildenhöhe Institute, Darmstadt. The gallery. Frankfurt am Main 1998-

- Hundertwasser. Edited by Minako Tsunoda. Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya 1999.

- Homage to Hundertwasser 1928/2000. Exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle. Alençon 2001.

- Ingeborg Flagge (Ed.): Friedensreich Hundertwasser, A Sunday Architect, Built Dreams and Longings. Catalog for the exhibition in the German Architecture Museum. The Frankfurt am Main Gallery 2005.

- Yoki Morimoto, Mayumi Hirano (Ed.): Remainders of an Ideal - The Vision and Practices of Hundertwasser. Catalog for the traveling exhibition in Japan 2006/2007. APT International, Tokyo 2006

- The unknown Hundertwasser. Catalog for the exhibition in the KunstHausWien on the occasion of the 80th birthday. Prestel Verlag, Munich 2008.

- Hundertwasser 2010 in Seoul. Exhibition catalog at Seoul Arts Center - Hangaram Design Museum. Maronie Books. Seoul 2010

- Andreas Hirsch (Ed.): Hundertwasser - The Art of the Green Path / The Art of the Green Path. Catalog for the exhibition in the KunstHausWien. Prestel Verlag, Munich 2011.

- Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Friedensreich Hundertwasser. La raccolta dei sogni. The harvest of dreams. The fruits of the dreams. Catalog for the exhibition in the Art Forum Würth (Capena) near Rome. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2008, ISBN 978-3-89929-137-7 .

- Christoph Grunenberg, Astrid Becker (ed.): Friedensreich Hundertwasser - Against the Grain. Works 1949–1970. Catalog for the exhibition in the Kunsthalle Bremen. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2012.

- Hundertwasser, Japan and the avant-garde. Catalog for the exhibition, Munich 2013, Hirmer Verlag, ISBN 978-3-7774-2043-1

- Sylvie Girardet, Nestor Salas (ed.): Dans la peau de Hundertwasser, Salut l'artiste. Catalog for the exhibition in the Musée en Herbe. Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 2013.

- Christian Gether, Stine Hoholt, Andrea Rygg Karberg (eds.): Hundertwasser. Catalog for the exhibition at the ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, Ishoj, Denmark 2014.

- Tayfun Belgin (Ed.): Hundertwasser - life lines. Catalog for the exhibition in the Osthaus Museum, Hagen. The gallery, Frankfurt am Main 2015.

- Daniel J. Schreiber (Ed.): Hundertwasser - Schön & Gut. Catalog for the exhibition in the Buchheim Museum, Bernried 2016.

- Hundertwasser 2016 in Seoul - The Green City. Catalog for the exhibition at the Sejong Museum of Art, Seoul 2016.

Exhibitions

Hundertwasser's works have been presented in countless exhibitions in galleries and museums around the world. This list represents a selection:

- Hundertwasser painting, Art Club, Vienna, 1952

- Studio Paul Facchetti, Paris, 1954

- Galerie H. Kamer, Paris, 1957

- Rétrospective Hundertwasser 1950–1960, Galerie Raymond Cordier, Paris, 1960

- Tokyo Gallery, Tokyo, 1961

- Hundertwasser is a present for Germany, Galerie Änne Abels, Cologne, 1963

- Traveling exhibition 1964/65: Hundertwasser: Kestner Society, Hanover; Kunsthalle Bern; Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum, Hagen; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; 20th Century Museum

- Traveling exhibition 1968/69: USA, University Art Museum, Berkeley; Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Arts Club of Chicago; The Galerie St. Etienne, New York; The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

- Aberbach Fine Art, New York, 1973

- Traveling exhibition 1973/74: Hundertwasser 1973 New Zealand, City of Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland; Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth; The New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, Wellington; City Art Gallery, Christchurch; City Art Gallery, Dunedin

- Traveling exhibition: Hundertwasser 1974 Australia: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Albert Hall, Canberra; Opera, Sydney

- Stowasser 1943 to Hundertwasser 1974, Albertina, Vienna, 1974

- House of Art, Munich, 1975

- Austria shows the continents Hundertwasser 1975-1987 world traveling museum exhibition. The exhibition was shown in 43 museums in 27 countries from 1975 to 1983.

- Albertina Graphics Exhibition 1974-1992 Traveling exhibition of graphic works, based on the exhibition in the Albertina Graphics Collection, Vienna, 1974

- Traveling exhibition 1979–1981: Hundertwasser Is Painting, Aberbach Fine Art, New York; Tokyo Gallery, Tokyo; Brockstedt Gallery, Hamburg; Hammerlunds Kunsthandel, Oslo; Galerie Würthle, Vienna

- Hundertwasser - Peintures Récentes, Artcurial, Paris, 1982

- Paintings by Hundertwasser, Aberbach Fine Art, New York, 1983

- Traveling exhibition 1989: Japan, Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, Tokyo; Iwaki City Art Museum, Fukushima; Ohara Museum of Art, Okayama

- Hundertwasser - Important works, Landau Fine Art, Montreal, 1994/1995

- Hundertwasser retrospective, Mathildenhöhe Institute, Darmstadt, 1998

- Touring exhibition 1998/99: Japan, Isetan Museum of Art, Tokyo, Museum “EKi”, Kyoto; Sakura City Museum of Art, Chiba

- Hundertwasser Architecture - From Utopia to Reality, KunstHausWien, Vienna, 2000/2001

- Traveling exhibition 2005/06: Germany, Friedensreich Hundertwasser - A Sunday architect. Built dreams and longings, Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM), Frankfurt; Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation, Gottorf Castle; Art forum of Bausparkasse Schwäbisch Hall AG, Schwäbisch Hall; Zwickau municipal museums, art collections, Zwickau

- The Art of Friedensreich Hundertwasser. A Magical Eccentric, Szépmüvészeti Museum, Budapest, 2007/2008

- HUNDERTWASSER 2010 IN SEOUL, Seoul Arts Center - Design Museum, Seoul, Korea, 2010/2011

- Hundertwasser - The art of the green way, 20 years KunstHausWien anniversary exhibition, KunstHausWien, Austria, 2011

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser - The harvest of dreams

- Hundertwasser exhibition in Adelsdorf

- Hundertwasser's last picture in the KunstHausWien

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser: Against the grain. Works from 1949 to 1970 in the Bremen Kunsthalle

- Hundertwasser: Japan and the Avant-garde , Belvedere Vienna, 2013

- Hundertwasser, Arken Museum, Ishøj, Denmark, 2014

- Hundertwasser - Lifelines, Osthaus Museum Hagen, Hagen, Germany, 2015

- Hundertwasser. Schön & Gut, Buchheim Museum, Bernried, Germany, 2016/2017

- Hundertwasser - The Green City, Sejong Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea, 2016/2017

- Hundertwasser - Play of colors , Britz Castle in the Berlin district of Britz , 2017

- Hundertwasser - En route pour le bonheur !, Musée de Millau et de Grands Causses, Millau, France, 2018

Works in museums all over the world

Original paintings in museums

- Academy of Fine Arts, Gemäldegalerie, Vienna, Austria

- Academy of Fine Arts, Kupferstichkabinett, Vienna, Austria

- Albertina, Vienna, Austria

- Albertina, Vienna - Essl Collection

- Albertina, Vienna - Batliner Collection

- Artothek des Bundes, Vienna, Austria

- Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

- Center National d'Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

- Hamburger Kunsthalle, Germany

- Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden, Norway

- Herbert Liaunig Private Foundation, Austria

- Hilti Foundation, Liechtenstein

- Iwaki City Art Museum, Japan

- KunstHausWien, Museum Hundertwasser, Vienna, Austria

- Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark

- MAK - Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria

- Mishkan Le'Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein-Harod, Israel

- MUMOK - Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation Vienna, Austria

- Musee d'Art Moderne, Troyes, France

- Museo del Novecento, Collezione Boschi di Stefano, Milan, Italy

- Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

- Museu de Arte Contemporanea da USP, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- Museum der Moderne - Rupertinum, Salzburg, Austria

- Museum of Arts and Crafts, Hamburg, Germany

- Nagoya City Art Museum, Japan

- National Gallery Prague / Narodni galerie v Praze, Czech Republic

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Austrian Gallery Belvedere, Vienna, Austria

- Ohara Museum of Art, Okayama, Japan

- Osthaus Museum Hagen, Germany

- Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy

- Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany

- Würth Collection, Künzelsau, Germany

- Saint Louis University, USA

- San Diego Museum of Art, USA

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

- Sprengel Museum Hannover, Germany

- Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Municipal art gallery Mannheim, Germany

- The Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

- The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Japan

- Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

Prints in museums

- Academy of Fine Arts, Kupferstichkabinett, Vienna, Austria

- Albertina, Vienna, Austria

- Albertina, Vienna - Essl Collection

- Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

- Cincinnati Art Museum , USA

- Archbishop's Cathedral and Diocesan Museum, Vienna, Austria

- Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, Germany

- KUNSTEN Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Denmark

- Kunsthalle Bremen, Germany

- KunstHausWien, Museum Hundertwasser, Vienna, Austria

- Kupferstichkabinett, National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Germany

- McMaster Museum of Art, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

- Muscarelle Museum of Art, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA

- Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Santiago de Chile

- Museum der Moderne - Rupertinum, Salzburg, Austria

- Museum landscape Hessen Kassel, Museum Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, graphic collection, Germany

- muzej moderne i suvremene umjetnosti - museum of modern and contemporary art, Rijeka, Croatia

- Nagoya City Art Museum, Japan

- Osthaus Museum Hagen, Germany

- Saint Louis University, USA

- Würth Collection, Künzelsau, Germany

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, USA

- Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, USA

- Sprengel Museum Hannover, Germany

- Takamatsu City Museum of Art, Japan

- The Gerard L. Cafesjian Collection, Yerevan, Armenia

- The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, USA

- The Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

- The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, USA

- The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Japan

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedensreich Hundertwasser in the catalog of the German National Library

- Website of the Hundertwasser non-profit private foundation

- Hundertwasser website

- Hundertwasser encyclopedia

- KunstHausWien - Hundertwasser Museum

- Website for the Hundertwasser House

- Entry on Friedensreich Hundertwasser in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Biography and works of Art Directory GmbH Munich

- Materials by and about Friedensreich Hundertwasser in the documenta archive

- Alexandra Matzner: Hundertwasser, Japan and the avant-garde . About Hundertwasser's early work and the influence of Japanese philosophy. For the exhibition “Hundertwasser, Japan and the Avant-garde” in the Belvedere from March 6th – 30th June 2013. Online at www.textezukunst.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- Friedensreich Hundertwasser in the original sound in the online archive of the Austrian media library

- Kerstin Hilt: December 15, 1928 - birthday of Friedensreich Hundertwasser WDR ZeitZeichen from December 15, 2013 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See the naming Pierre Restany: Die Macht der Kunst, Hundertwasser. The painter-king with the five skins . Taschen, Cologne 2003, ISBN 978-3-8228-6598-9 , p. 16

- ↑ It was not until much later that Hundertwasser found out that the name Stowasser is etymologically derived from the Tyrolean dialect and actually means "backwater" (standing water). See Schmied, Wieland (ed.): Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné / Werkverzeichnis. Vol. I: Schmied, Wieland: Personality, Life, Work. Taschen: Köln 2000, p. 35

- ↑ See also Andrea C. Fürst, in: Hundertwasser in the colors of his paintbrush London: Gudrun Publishing, 2017, p. 8

- ↑ Andrea C. Fürst, in: Hundertwasser in the colors of his paintbrush London: Gudrun Publishing, 2017, p. 9

- ^ Bazon Brock, wavy lines in dammed water, in: Hundertwasser, Gegen den Strich, catalog of the exhibition, Kunsthalle Bremen, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 212, p. 160

- ↑ Alexandra Matzner: Hundertwasser, Japan and the avant-garde . About the exhibition “Hundertwasser, Japan and the Avant-garde” in the Belvedere 6 March – 30. June 2013. Online , accessed on January 18, 2016.

- ↑ See Wieland Schmied (ed.), Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné / Werkverzeichnis. Vol. I: Schmied, Wieland: Personality, Life, Work. Taschen: Köln 2000, p. 35

- ↑ cf. Jasper Sharp, Austria and the Venice Biennale 1895-2013, Nuremberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2013, pp. 68, 331-333

- ↑ see the imprints of various art prints with copyright Gruener Janura AG as well as catalogs such as B. Hundertwasser Friedensreich Regentag, cat. Of the exhibition Museum Ludwig, Cologne 1980

- ↑ a b Andreas Wetz: Hundertwasser's lost millionaire inheritance. In: Die Presse.com. , February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Erika Schmied, W. Schmied: Hundertwasser's paradises. The hidden life of Friedrich Stowasser. Knesebeck, Munich 2003, ISBN 978-3-89660-179-7 .

- ↑ cf. Erich Mursch-Radlgruber, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, an ecological visionary, in: Cat. Of the exhibition in the KunstHausWien: Hundertwasser - The Art of the Green Way, Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2011, p. 157

- ↑ Markus R. Leeb: 150 million gone! Hundertwasser's daughter: "I was cheated of my inheritance". In: News , August 1, 2013, pp. 16ff.

- ↑ http://www.post.at/footer_ueber_uns_presse_pressearchiv_2004_3927.php

- ↑ Conrad Seidl: Hainburg occupiers rely on “double strategy” . In: Kurier , December 12, 1984.

- ↑ Pictures of the number boards ( Memento from November 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) in the teacher web .

- ↑ Questions to Friedensreich Hundertwasser . In: Der Spiegel . No. 48 , 1988, pp. 259 ( online - November 28, 1988 , interview).

- ↑ Schurian, Walter (ed.): Hundertwasser - Beautiful ways, thoughts on art and life, texts and manifestos by Hundertwasser, Munich: Langen Müller Verlag, 2004, pp. 55f, 329

- ↑ https://www.kunsthauswien.com/de/

- ^ Schmied, Wieland (ed.): Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné. Vol. I: Schmied, Wieland: Personality, Life, Work. Vol. II: Fürst, Andrea Christa: Catalog raisonné. Köln / Cologne: Taschen, 2002.

- ↑ http://www.hundwasserfoundation.org/impressum/

- ↑ ORF Culture Monday . November 16, 2008.

- ↑ "I am not allowed to, Joram has forbidden me to do so".In: Die Presse , April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Cf. Art Souvenir - Hundertwasser in the colors of his paintbrush, with a text by Andrea Christa Fürst, London: Gudrun publishing, 2017, p. 7f.

- ↑ From: Hundertwasser KunstHausWien. Taschen, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8228-6613-X .

- ↑ See Art Souvenir - Hundertwasser in the colors of his paintbrush, with a text by Andrea Christa Fürst, Gudrun publishing, London 2017, p. 13f.

- ↑ Hundertwasser 1928-2000 Catalog Raisonné, Volume 1: Andrea C. Fürst, Cologne: Taschen 2002, p. 52

- ↑ Koschatzky, Walter: Friedensreich Hundertwasser. The complete graphic work 1951–1986, Friborg: Office du Livre; Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall: Orell Füssli Verlag, 1986.

- ↑ See Hundertwasser 1928-2000 Catalog Raisonné, Volume 1: Andrea C. Fürst, Cologne: Taschen 2002, p. 900 ff

- ↑ Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné. Vol. II: Fürst, Andrea Christa: Catalog raisonné. Köln / Cologne: Taschen, 2002, p. 737 f.

- ↑ Koschatzky, Walter: Friedensreich Hundertwasser. The complete graphic work 1951–1986, Friborg: Office du Livre; Zurich / Schwäbisch Hall: Orell Füssli Verlag, 1986.

- ↑ See Hundertwasser's text in: Catalog of the exhibition: Hundertwasser, Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna 1978, p. 6

- ↑ See Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné, Volume 2 by Andrea Christa Fürst, Cologne: Taschen 2002, p. 53

- ^ Moldy manifestation against rationalism in architecture. In: hundwasser.at , 1958/1959/1964.

- ↑ See: Wieland Schmied: Hundertwasser 1928–2000. Catalog raisonné. Cologne: Taschen 2000/2002, Volume 2, p. 1167.

- ↑ ibid p. 1177

- ↑ HUNDERTWASSER The art of the green way. The Art of the Green Path, pp. 128f + 206f, editor Andreas Hirsch for KUNST HAUS WIEN, Prestel Verlag; Bilingual, 2011

- ↑ See: Wieland Schmied: Hundertwasser 1928–2000. Catalog raisonné. Cologne: Taschen 2000/2002, Volume 2, p. 1178

- ↑ On this fundamental tendency cf. Robert Schediwy: Hundertwasser's houses. Edition Tusch, Vienna 1999.

- ↑ Cf. Liesbeth Wächter-Böhm in Die Presse of December 31, 1993 or Dietmar Steiner in the Kurier of April 10, 1994. Wächter-Böhm described the spread of the Hundertwasserbauten as "bubonic plague", Steiner as "cancerous ulcer".

- ↑ Manifesto The Holy Shit ( Memento from April 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ quoted in: Robert Schediwy: Hundertwasser's houses. Edition Tusch, Vienna 1999, p. 12.

- ↑ http://www.grugapark.de/hundwasserhaus.html

- ↑ Fnaz Dosch: Danube yards with history, Suttonverlag, Erfurt 2011. 46. Online . Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Hundertwasser 1928-2000, Catalog Raisonné, Volume 1: Andrea C. Fürst, Cologne: Taschen 2002, p. 52

- ↑ Hundertwasser's rainy day. Documentary about Friedensreich Hundertwasser 1972. Schamoni Film und Medien GmbH, accessed on January 1, 2017 .

- ↑ Website of the Hundertwasser Charitable Private Foundation

- ↑ a b Company directory and product database Austria

- ↑ http://hundwasserpark.com/

- ↑ Friedensreich Hundertwasser - The harvest of dreams. Würth Collection in Forum Würth Arlesheim, accessed February 12, 2014

- ^ Hundertwasser exhibition in Adelsdorf , from September 19 to October 11, 2009

- ↑ Hundertwasser's last picture in the KunstHausWien : Smoke in Green (accessed on February 19, 2010)

- ↑ Special exhibition 2012/13 Friedensreich Hundertwasser: Against the Grain. Works from 1949 to 1970 in the Bremen Kunsthalle , accessed on October 22, 2012

- ↑ Hundertwasser: Japan und die Avantgarde, Belvedere Vienna, 2013 , accessed on June 22, 2015

- ↑ District Office Neukölln, press release , accessed on June 21, 2017

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hundertwasser, Friedensreich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Stowasser, Friedrich (maiden name); Hundertwasser, Friedensreich Regentag dark colored |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 15, 1928 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 19, 2000 |

| Place of death | on Queen Elizabeth 2 off Australia |