History and development of the encyclopedia

This article deals primarily with the history of the encyclopedia in Europe and America . The development of encyclopedias in other cultures is presented separately: encyclopedias from the Chinese culture , encyclopedias from the Islamic culture .

overview

Although the word is traced back to the ancient Greek enkyklios paideia , forerunners of encyclopedias did not emerge until the Roman culture. Word creations constructed from ancient Greek, for example, are typical of the writing style of Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560).

The term encyclopedia appeared in the title of printed descriptions of knowledge at the beginning of the 16th century. The first known classification of the sciences, which was titled as an encyclopedia , is the Encyclopedia by Johannes Aventinus , which appeared in print in Ingolstadt in 1517 . First in 1541 (possibly as early as 1529), when Joachim Sterck van Ringelbergh ( J. Fortius Ringelbergius ) named the anthology of his works Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia . An early evidence of the expression can be found in Sir Thomas Elyot , The Boke named The Governour, London 1531. In 1559 the Encyclopaedia seu orbis disciplinarum tam sacrarum quam prophanarum epistemon by Paul Scalich was printed, and Johann Heinrich Alsted's well-known Encyclopaedia Cursus Philosophici was published no later than 1630 .

Most of the early works are structured according to the systematic ordering principle, which has been designed with great variance: see encyclopedia (knowledge order) . The only notable exception is the alphabetically structured Suda from 10/11 in Greek . Century.

At the end of the 16th century, Francis Bacon began a methodological and systematic reorganization of the sciences. Increasing secularization , the Reformation and the Enlightenment significantly influenced the development of the encyclopedia, and vice versa. Denis Diderot recently built his Encyclopédie on a tree of knowledge .

National-language works that replaced the Latin language were published in the 18th century. The first encyclopedias were also published that lemmatized the material and presented it in alphabetical order . As early as 1728, Ephraim Chambers introduced the linking of articles through cross-references in his alphabetically arranged Cyclopaedia . This combination of two principles of order was groundbreaking and has been the standard for encyclopedic and other reference works since the 19th century.

Created as a bridge between otherwise incompatible principles, cross-references were soon used to circumvent censorship , namely in Diderot's Encyclopédie . In terms of breadth and depth of presentation, this work became the model for all subsequent encyclopedias. The first special encyclopedias appeared in the 18th century .

The further increase in the depth of representation that began at the end of the 18th century led the printed encyclopedia to a dead end. The works became so extensive and required such a long processing time that they could no longer meet the needs of those interested. They therefore remained unfinished. The encyclopedias of Panckoucke and Ersch / Gruber were still the largest ever printed reference books.

In the crisis of the encyclopedia, the form of the conversation lexicon emerged from the beginning of the 19th century , which combined rapid appearance with sufficient depth. In view of the failure of the Grand Encyclopedias - the work by Erf / Gruber was discontinued in 1889 - the conversational encyclopedias increased their depth of representation so that encyclopedias were available again at the end of the 19th century.

From around the 1980s, English established itself as the new universal language in the natural sciences. In the course of the knowledge explosion of the information and knowledge society and the fundamental uncertainties of postmodernism , the foundation of the encyclopedia is questioned: The paradigm of positive knowledge is discussed as well as the premise of a self-contained knowledge space. At the same time, current technologies such as the Internet bring unprecedented possibilities for global acquisition, storage and networking of knowledge.

Antiquity: preforms of the encyclopedia

Greek culture

The term Enkyklios paideia ("circle of education", Latin later orbis doctrinae ) is found for the first time in Isocrates and the Sophists and means in Hippias von Elis (around 400 BC) "universal education ", which a free-born youth can acquire have: grammar , music , geometry , astronomy and gymnastics .

The beginnings of the systematic encyclopedia are mostly traced back to the Greek philosopher Speusippos , the nephew and pupil of Plato , who continued the academy founded by Plato : Around 370 BC. A study of the similar phenomena occurring in the animal and plant kingdoms arose, the special encyclopedia Homoia, of which only a few fragments have survived.

Other philosophers, such as Aristotle , wrote treatises on the knowledge of their time, but no encyclopedia was created.

Roman culture

The statesman and writer Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder wrote around 150 BC. BC, shortly before his death, the Libri ad Marcum filium (books to the son Marcus). They deal with the disciplines of agriculture, medicine, rhetoric and war science with educational objectives, so they are an early (the first Latin) special encyclopedia.

The first approach to a comprehensive encyclopedia was the Disciplinarum libri IX (short: Disciplinæ , around 30 BC) by Marcus Terentius Varro . He added the subjects of Orbis doctrinae the medicine and architecture . Only fragments of his 41 books have survived.

The oldest verifiable alphabetically structured encyclopedia was written by the Latin grammarian Marcus Verrius Flaccus around the turn of the ages; his lexical work De significatu verborum (About the meaning of the [rare Latin] words) is missing and only about the texts of the Roman grammarian Sextus Pompeius Festus (2nd half of the 2nd century) and the historian Paulus Diaconus (8th century) known.

Artes liberales

The system of the seven liberal arts (Septem artes liberales) was first bindingly established in the 5th century (dating disputed) by Varro's late antique successor Martianus Capella in his allegorical encyclopedia De nuptiis philologiæ et Mercurii (On the marriage of Philologias with Mercury) :

- Trivium - Three linguistic subjects, namely grammar , dialectics , rhetoric .

- Quadrivium - Four math subjects: arithmetic , geometry , astronomy , music .

The Roman historian Cassiodorus (6th century) and later the Spanish scholar Isidore of Seville also base their work on this canon. De nuptiis philologiæ et Mercurii was an important teaching work in the Middle Ages and passed on to the Roman system, the division of which was largely abandoned with the emergence of the Enlightenment and humanism .

The natural history of Pliny the Elder

The oldest complete systematic special encyclopedia in Latin was written by the Roman historian and writer Pliny the Elder . His Historiae naturalis libri XXXVII (natural history in 37 volumes) was written by 79 AD and comprised a total of 2,493 chapters on the topics of cosmology , geography , ethnology , anthropology , physiology , zoology , botany , herbal and animal remedies ( pharmacology ), mineralogy and Metallurgy .

According to the directory, works by almost 500 authors were processed, including around 100 sources. The Naturalis historia was printed in Venice as early as 1469 . The first German translation of Books 7 to 11 (Anthropology, Physiology, Zoology) was published in Strasbourg in 1543 under the title Natural History Five Books .

A special encyclopedia from Varro is also known, but not preserved: the Roman antiquity Rerum humanarum et divinarum antiquitates.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

In the Middle Ages , allegorical textbooks of the Artes liberales appeared , later compendia of all sciences and arts, which were structured according to systematic principles such as the six-day work or the catechism or based on the course of the year (calendar). Typical work titles are Thesaurus (treasure), Gazophylacium (treasure house), Aurifodina (gold mine), Promptuarium (armory), Theatrum (scene) or Acerra (vessel). More advanced works use tree metaphors such as the Arbor porphyriana .

The medieval works are consistently structured systematically (instead of alphabetically) and written in Latin regardless of the country of origin . National-language encyclopedias emerged in the late Middle Ages and in the early modern period. The only significant exception is the Byzantine Suda , which is written in Greek and alphabetically structured .

Allegorical textbooks of the Artes Liberales

Important works of the Artes Liberales :

- Martianus Capellas De nuptiis Mercurii et Philologiae from the 5th century

- Cassiodors : Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum from the 6th century

- Gregor Reisch's Margarita Philosophica , a handbook of the sciences, which was distributed in numerous editions from 1503 (including reprints by Johann Grüninger ) and was considered the authoritative encyclopedic textbook for students of the seven liberal arts for more than 100 years .

Systematic compendia of all sciences and arts

First compendia of all sciences and arts are without exception systematically structured, but are not necessarily limited to the disciplines of the Artes Liberales. These are collections of materials without any philosophical processing of the content. The most important:

-

Isidore of Seville , "the teacher of Spain", published the encyclopedia Etymologiarum sive originum libri XX also Origines, Originum seu etymologiarum libri XX (twenty books of the origins or etymologies ) around 630 . He supplements the Artes Liberales with an outline of the then known world history. This “land register of the whole Middle Ages” ( Ernst Robert Curtius ) also contains a cycling map .

The Etymologiae, which were considered a standard work for centuries, were first printed in Augsburg in 1472 by Günther Zainer ; Isidor's map is the oldest printed map in the West. - Rabanus Maurus (also Hrabanus Maurus ), student of Alcuin . The Praeceptor Germaniae (Germany's teacher) published an expanded new edition of some books from Isidor's encyclopedia in 847: The 22-volume De rerum naturis seu de universo was first printed in 1473. Like Isidore, Hrabanus compiled the knowledge of the time from the works of ancient and early medieval authors. What is remarkable, however, is his reassessment of medicine : In his list of clerical educational goals, he demands - unthinkable before him - basic medical knowledge: "The person who came up with the claim to want to cure illness was downright guilty of the presumptuous original sin of superbia , while he sought to intervene in God's plan of salvation in a corrective manner ” (Note 1) .

- The Flemish Benedictine canon Lambert de Saint-Omer is considered to be the author of Liber Floridus , written around 1120 , a quasi-chronological narrative of world events since the creation of the world. The work is a compilation of more than 100 different works by other authors, in which biblical, astronomical, geographical and natural-philosophical topics are dealt with.

- Herrad von Landsberg (also Herrad von Hohenburg, died after 1196) was abbess of the Hohenburg monastery on Mount Odile in Alsace. She created the Hortus Deliciarum ( Garden of Delicacies ) between 1175 and 1195 . The original of the encyclopedic work on the instruction of nuns, illustrated with 344 miniatures, was burned in Strasbourg in 1870, but a facsimile from 1818, which is fairly true to the original, still exists today.

- In the 13th century, the Franciscan scholastic Bartholomaeus Anglicus wrote the Liber de proprietatibus rerum . The presentation of the micro- and macrocosm, which is divided into 19 sections, is one of the most important reference works of the Middle Ages and one of the first to also take the flora into account. In 1372, the Augustinian Jean Corbichon translated the work into French as Le Proprietaire des choses très utile et profitable aux corps humains on behalf of King Charles V. New editions were printed in Rouen and Paris in 1517 and 1525.

- Also in the 13th century, the Dominican monk Vinzenz von Beauvais wrote what is probably the most important encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, the "Great Mirror" . It had processed more than 2,000 theological writings and works by Greek, Hebrew and Roman authors in 80 books. The Speculum maius, first printed in 1474 (fourth and final edition: Douai 1624 in 32 books), consists of three parts, divided into five volumes:

- Volumes 1–2: Speculum historiale - a historiography of the expulsion from paradise up to the year 1244

- Volume 3: Speculum doctrinale

- Volumes 4–5: Speculum naturale - a

- A planned fourth part, Speculum morale, was not implemented.

Significant follow-up works:

- Joachim Fortius Ringelberg , Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia (Basel, 1538).

- Stanislav Pavao Skalić (Paul Scalich), theologian, humanist and follower of Ramon Llull was probably the first to use the term Encyclopaedia in the title of his Encyclopaedia seu orbis disciplinarum tam sacrarum quam prophanarum epistemon…, Basel 1559.

- In 1565, after the death of his stepfather Conrad Lycosthenes , the Swiss philologist and physician Theodor Zwinger the Elder published the Theatrum Vitae Humanae (scene [perhaps rather a showcase] of human life) , a kind of universal encyclopedia in Latin that was systematically based on the Aristotelian-Ramist method is structured. The following editions of 1571, 1586 and 1604 were each expanded. What is remarkable about Zwinger's work is u. a. also the term Theatrum , which was used in numerous publications in the early modern period. Zwinger was probably referring to Giulio Camillo's idea of the memory theater (Florence 1550), which had only been published a few years earlier , with which the art of memory was to be revived in the spirit of Neoplatonism .

-

Johann Heinrich Alsted published the seven-volume Encyclopaedia Cursus Philosophici in Herborn around 1630 - the work is one of the last great systematically structured encyclopedias in Latin. It uses llull's method to systematize the sciences (see Ars generalis ultima and Arbor scientiae ).

Alsted's approach that all knowledge can be brought to everyone with suitable didactics and methodology of teaching and learning had a lasting impact on the pedagogue Comenius and the Hungarian encyclopaedist Apáczai Csere János (1625–1659). - Laurens Beyerlinck : Magnum theatrum vitae humanae in 7 volumes - a revision of Zwinger's encyclopedia, first edition: Cologne 1631; Index volume by Caspar Princtius , Cologne 1631 and Venice 1707.

Alphabetically structured encyclopedias

- The work known today as Suda is a 10th-century Byzantine alphabetical lexicon written in ancient Greek and has never been fully translated into a living language . Until about 1930 it was ascribed to an author named Suidas , who probably didn't exist - the title probably means “fortress” [of knowledge].

The Suda contains more than 32,000 articles on the lives and works of ancient authors and on ancient geography and history . She often "cites" freely or relies on unreliable sources, but is unique, to which the classic bon mot refers: "A sheep is Suidas, but one with golden wool." (Presumably by Justus Lipsius , 1547–1606).

National-language encyclopedias

- As early as 1265, the Italian poet and scholar Brunetto Latini wrote the first important lay encyclopedia in French in Paris: Li livres dou trésor (the treasure books) were intended to reach a larger readership and, above all, to impart practical knowledge, and were therefore a first forerunner of the conversation encyclopedias .

- Konrad von Megenberg wrote the book of nature around 1350 , a general, already quite systematic natural history, which is interesting as evidence of the knowledge of the time and at the same time important in terms of cultural history due to the citing of many legends and the like. The work first appeared without a place or year, then Augsburg in 1475 and then more often, most recently re-edited by Luff and Steer, Tübingen 2003.

Specialized encyclopedias are similar to medieval ones

- Summae (which students were dictated to memorize ) and

- Specula (a title often chosen for legal books, example: Vincent de Beauvais ).

Modern Times: Francis Bacon and the Century of Encyclopedias

The model for the editors of modern encyclopedias was the English philosopher Francis Bacon , who listed a catalog of 130 individual sciences in his 1620 work Preparative toward a Natural and Experimental History . This high level of differentiation for his time was a point of reference for all of his successors. In the preface to his Encyclopédie Diderot referred to Bacon as a model. Bacon began to publish an encyclopedia based on his design, but was only able to complete two issues due to his early death (1622–23).

The term encyclopedia in the Anglo-Saxon world can be traced back to the British physicist Thomas Browne , who noted in 1646 in his compendium of disproved common errors, Pseudodoxia Epidemica :

[…] and therefore in this Encyclopedia and round of knowledge, […] .

In the age of Enlightenment at the end of the 17th century, but especially in the 18th, was "Encyclopedia" the epitome of a work that one to reason based compendium contemporary knowledge of mankind claimed to represent. Those who contributed we call encyclopedists .

The Lexicon technicum (1704)

The mathematician John Harris published the Lexicon technicum (Lexicon technicum: or, an universal english dictionary of arts and sciences) in London in 1704 , which is considered the first general encyclopedia with a focus on technology and science. It is also the first alphabetically ordered encyclopedia in English and was the model for Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia. It was later recognized by Diderot as one of his sources.

The General Lexicon of Arts and Sciences (1721)

The General Lexicon of Arts and Sciences was first published by Johann Theodor Jablonski .

Cyclopaedia (1728)

Ephraim Chambers published the two-volume Cyclopaedia in London in 1728 : or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences. It is considered to be the first English-language encyclopedia and probably the first to use cross-references systematically.

-

[...] Chambers is clearly the father of the modern encyclopaedia throughout the world. […] Chambers's Cyclopaedia is particularly remarkable for its elaborate system of cross-references, and for the broadening of Harris's coverage to include more of the humanities […]

(Robert Collison, Encyclopaedias: Their history throughout the ages ).

"The" Encyclopédie (1751–1780)

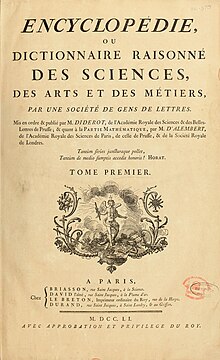

The most famous early encyclopedia is the French-language Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers , published from 1751 , which was edited by the Enlightenmentists Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert ; the title describes encyclopedia as “dictionnaire raisonné”, “reasonably structured [that is, critically thought out] dictionary”. The authors note:

-

In the lexical summary of everything that belongs in the fields of science, art and craft, the aim must be to make their mutual interdependence visible and to grasp the principles on which they are based more precisely with the aid of these cross-connections [...] To paint a general picture of the efforts of the human spirit in all areas and in all centuries.

(D'Alembert in the preface)

- Diderot wrote to his friend Sophie Volland about the enlightenment goal:

This work will surely bring about a transformation of the spirits with it in time, and I hope that the tyrants, the oppressors, the fanatics and the intolerants will not win. We will have served humanity [...]

Started as a translation of Chambers' Cyclopaedia, an independent work was created under Diderot. It is the last important encyclopedia that is based on a tree of knowledge in the manner of Francis Bacon , but already deviates from it in important places; it thus initiates an epistemological change of direction that transformed the topography of all human knowledge (Robert Darnton).

The publication, which began in 1751, was first completed in 1772 with the 28th volume: 17 text volumes contain around 18,000 pages with 71,818 articles, 11 volumes with illustrations contain 2,885 illustrations and 2,575 explanations of the figures. Between 1776 and 1780 a total of seven additional volumes ("Suppléments") were published.

Accompanied by mistrust and prohibitions by church and state, the work of the encyclopedists initiated the militant phase of the Enlightenment and with it the French Revolution .

The enormous financial success of the Encyclopédie and the disadvantages of the alphabetical arrangement of the lemmas prompted the publisher of the supplements , Charles-Joseph Panckoucke , to revise it. The material was divided into more than 50 subject areas, for which specialist dictionaries were created. Panckoucke's Encyclopédie méthodique appeared in 206 volumes between 1781 and (with successors) 1832. Because of the Napoleonic wars, this work did not bring the hoped-for financial success.

Encyclopædia Britannica (1768–1771)

The Encyclopædia Britannica published by William Smellie between 1768 and 1771 began as a three-volume work.

Encyclopedic dictionaries of history, geography and biography

- Louis Moréri published Le grand dictionaire historique , ou mélange curieux de l'histoire sacrée et profane in Lyon in 1674 . The work was revised and translated several times and had at least 20 editions, most recently in Paris in 1759. It is important because it heralds the era of national-language lexicons, but also because it was Pierre Bayle's impetus for the Dictionnaire historique et critique .

- The Biblioteca universale Sacro-Profana of the cosmographer and cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli is one of the first encyclopedias in Italian. The alphabetically structured work was originally designed for 45 volumes with 300,000 headwords, of which only six or seven volumes appeared in Venice between 1701 and 1706. (The letter A already comprised four volumes and almost 2,700 terms). The work is considered to be one of the first conversational dictionaries.

- Based on the model of Moréris Grand dictionnaire , the Basel lexicographer Johann Jakob Hofmann (1635–1706) created the Lexicon universale historico-geographico-chronologico-poetico-philologicum (short: Lexicon Universale ) in Latin , first published in Basel in 1677 with two copies Volumes; six years later - 1683 - three supplementary volumes (Continuatio) were published in Basel. In 1698 the lexicon and supplementary volumes were merged and a new four-volume edition appeared in Leiden under the title Lexicon universale historiam sacram et profanum omnis aevi, omniumque Gentium, chronologiam ad haec usque tempore, geographiam et veteris et novi orbis, principum per omnes terrasoria familiarum ab omni mem repetitam geneologiam, tum mythologiam, ritus, caerimonias, omnemqueveterum antiquitatem, ex philologiae fontibus haustam, vivorum, ingenio atque eruditione celebrium enarrationem copiosissimam, praeterea animatium, plantarum, metallorum, lapidum, gemmarum explan, nomina, naturansas .

German-language encyclopedias

Systematically structured encyclopedias

- Johann Joachim Eschenburg , Textbook of Science (1792)

- Wilhelm Traugott Krug , Encyclopedia of Sciences (1796–1798)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel , Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1817).

- Contemporary culture was started in the German Empire by Paul Hinneberg and published until the Weimar Republic (1905–1926). The concept of the Encyclopédie should be realized again with the then current state of knowledge.

Special encyclopedias

- Johann Gottfried Gregorii alias MELISSANTES (1685–1770), Die curieuse OROGRAPHIA, or accurate description of the most famous mountains / In Europa / Asia / Africa and America [Lexicon of the mountains], Leipzig and Frankfurt 1715

- Johann Georg Krünitz (1728–1796), see Oeconomische Encyclopädie

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica

Universal encyclopedias

-

Johann Heinrich Zedler (1706–1751)

The bookseller and publisher Johann Heinrich Zedler published the Great Complete Universal Lexicon of All Sciences and Arts (Leipzig 1731–1754) between 1731 and 1754 .

The work, briefly named Zedler's Lexicon after the publisher, is the first German-language encyclopedia and is considered to be the largest universal lexicon of the West ever printed ; it comprises 64 volumes and 4 supplements with around 750,000 articles on 62,571 pages.

The Zedler Lexicon was the first encyclopedia to which an editorial team of specialist scholars worked, including Johann Christoph Gottsched . The Zedler was also the first encyclopedia to contain biographies of living personalities. -

Johann Samuelersch (1766–1828) and Johann Gottfried Gruber (1774–1851)

The librarian Versch and the writer Gruber published the General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts , which was conceived as the successor to the Zedlerian Lexicon. The work is considered the most extensive encyclopedia in the West, a prototypical document of German idealism .

The work has remained unfinished. The volumes Aa – Gy, Ha – Li, Oa – Ph with a total of 78,000 pages have been published. The gigantic work published in Leipzig 1818–89, even in its fragmentary state, is still so informative and productive for research today that it was reprinted in 1969 by the Academic Printing and Publishing Society in Graz.

"Frankfurter Encyclopedia" project (from 1788)

- This is considered to be the first German work to have this name in its title. It was published from 1778 by the Gießen pedagogue and history professor Heinrich Martin Gottfried Köster in Frankfurt am Main as the German Encyclopedia ( German Encyclopedia or general real dictionary of all arts and sciences, also Frankfurt Encyclopedia ). The work was continued from the 18th volume due to Köster's death by Johann Friedrich Roos , but remained unfinished (A – Ky); the 23rd and last volume appeared in 1804, a volume with copper plates was submitted in 1807.

Real Encyclopedia and Conversation Lexicon

The encyclopedia had found public and form in the Enlightenment and in the 18th century. In the 19th century created for the emerging educated middle encyclopedias like Meyers encyclopedia (1839), Herder Conversations-Lexikon (1854) (later The big Herder ) or Brockhaus (1808):

Educated citizens searched the knowledge base for conversation , but wanted as a sign of education and social status also elevated literary language mastered. While an encyclopedia is a general educational work of knowledge, a lexicon is a reference work for general education , and a dictionary puts emphasis on the language itself ( Duden ), conversational lexicons (predecessor: The Suda , 10th or 11th century) fulfill several tasks at the same time. The transition to the encyclopedia is fluid. For history and development see Konversationslexikon .

- Johann Joachim Eschenburg , Textbook of Science (Berlin 1792, 3rd edition 1809)

- K. Ch. Erh. Schmid, General Encyclopedia and Methodology of Sciences (Jena 1810)

- KA Schaller, encyclopedia and methodology of science for prospective students (Magdeburg 1812)

- Kirchner, Academic Propaedeutics (Leipzig 1842) and Hodegetics (Leipzig 1852)

GDR

- The VEB Bibliographisches Institut and VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie published the Lexicon A – Z in one volume in Leipzig in 1953 ; it is the first Marxist lexicon in German. In the same ideology are written:

Meyers Neues Lexikon . 8 vols. A – Z 1961–64. Vol. 9: Additions to subject terms and geograph. Proper names, 1969. Leipzig, VEB Bibliographisches Institut (= 1st edition).

Meyer's New Lexicon . 2nd edition, 15 vols. A – Z 1971–77. Vol. 16: Register A – Z, 1978. Vol. 17: Atlas (Maps), 1978. Vol. 18: Atlas (Register), 1978. Leipzig, VEB Bibliographisches Institut.

Meyer's universal dictionary in 4 volumes. Leipzig, VEB Bibliographisches Institut, 1978–80. - Short edition of the previous one.

Austria

In addition to the widespread German-language encyclopedias (not to forget the Brno reprint of Krünitz), nationally oriented works were created from 1835:

-

Franz Gräffer and Johann Jakob Czikann

Between 1835 and 1837 the Austrian National Encyclopedia, or alphabetical presentation of the most remarkable peculiarities of the Austrian Empire , appeared in Vienna in six volumes and a supplement (1838), the first nationally oriented Austrian encyclopedia.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the Basel librarian Jakob Christoph Iselin recruited employees in several cantons in order to improve the German edition of the Grand dictionnaire historique (Leipzig, 1709) by Louis Moréri, which was incorrect with regard to Switzerland , and in 1726 brought his newly-multiplied historical and geographic material General Lexicon […] in four folio volumes (which Pierre Roques then used for his Moréri edition from 1731 to 1732).

-

General Helvetic, Federal, or Swiss Lexicon

The 20-volume work with around 20,000 keywords on 11,368 pages, written by Zurich banker and mayor Johann Jacob Leu (1689–1768) between 1747 and 1765, is considered the most important representative of the nationally oriented Swiss lexicons of the 18th century. Century.

Between 1786 and 1795, the pharmacist Hans Jakob Holzhalb (1720–1807) created six supplementary volumes with a total of 3,826 pages. - Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HBLS), 1921–1934, by Heinrich Türler , Marcel Godet and Victor Attinger , seven volumes and supplements.

- Swiss lexicon in six volumes . Editor-in-chief: Wilhelm Ziehr ; Central editorial office: Antje Ziehr ... et al. Lucerne: Verlag Schweizer Lexikon, Mengis & Ziehr, 1992-1993. - Corrected, improved, supplemented and updated edition: popular edition in twelve volumes. Visp: Swiss Lexicon, Mengis + Ziehr, 1998-1999.

-

Historical Lexicon of Switzerland (HLS and e-HLS)

A follow-up project initiated in 1988 to the Historical-Biographical Lexicon. It was published - a unique specimen of lexicography - in parallel in the three main official languages, both in book form and as an online version. In the fourth national language, Romansh , a two-volume partial edition limited to the articles on the Rhaetian area has been published in book form, the Lexicon istoric retic (LIR). The e-LIR has also been online since 2004 .

Foreign language encyclopedias of the 19th and 20th centuries and the present

Encyclopedic dictionaries on religions, cultures and ethnic groups

-

Real Encyclopedia of Judaism

The lexicographer and regional rabbi of Mecklenburg Jacob Hamburger (* Loslau in Oberschlesien 1826, † Strelitz in Mecklenburg-Strelitz 1911) published this first lexical reference work on Judaism in seven volumes between 1886 and 1900 in Leipzig. - The oldest Jewish encyclopedia in English, Jewish encyclopedia, appeared between 1901 and 1906 in New York and London with a total of 12 volumes.

- The first Jewish encyclopedia in Russian, Jevrejskaja entsiklopedija, appeared between 1906 and 1913 in St. Petersburg with a total of 16 volumes.

- The 32-volume Encyclopaedia Hebraica was published in Jerusalem and in Hebrew between 1949 and 1980, i.e. immediately after the establishment of the State of Israel (1948).

Cultural, State and National Encyclopedias of the 19th and 20th Centuries

- Kobers Slovník Naučný , also called Riegers (after the editor), the first Czech-language encyclopedia in Bohemia, published between 1858 and 1874 in 14 volumes by the publisher Ignaz Leopold Kober , Prague .

- Ottův slovník naučný , the second Czech-language encyclopedia, published between 1888 and 1909 in 28 volumes by the publisher Jan Otto .

- Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeo-americana , Enciclopedia Espasa for short , published between 1905 and 1930 and updated regularly to this day. With its 90 to 124 volumes, over 900,000 articles or over 200 million words, the Enciclopédia universal is the most extensive printed encyclopedia in the world (see also comparison of some encyclopedias )

-

Bolschaja Russkaja Enziklopedia ( Bol'schaja sovjetskaja enciklopedija , BSE; German: "Große Sowjetenzyklopädie" or Great Soviet Encyclopedia ) in Russian

- Edition, Bolsaja Sovetskaja Enciklopedija , published by the shareholder company Soviet Encyclopedia , from 1930 State Encyclopedia

- Edition, arranged on the instructions of the Council of Ministers in 1949: Bolsaja Sovetskaja Enciklopedija , published by the Moscow State Academy, 50 volumes plus a supplementary volume, Moscow 1949–1958; 2 reg. Volumes 1960.

- Enciclopedia Italiana (1929-1937)

- Great Chinese Encyclopedia or Encyclopaedia Sinica (Chinese: Zhongguo da baike quanshu ), (1980–1993), 74 volumes

- Swedish National Encyclopedia ( Nationalencyklopedin ), 1989 to 1996, 20 volumes (Verlag Bra Böcker AB).

- Encyclopaedia Judaica (published from 1971, in English; Jerusalem: Keter; New York: Macmillan), goes back to the German Encyclopaedia Judaica (Berlin: Eschkol 1928–1934; only partially published, volumes A – Lyra).

- Illustrated Australian Encyclopaedia, (published from 1925 by Arthur Wilberforce Jose and Herbert James Carter)

- Swiss lexicon in 7 volumes , edited from 1945 by Gustav Keckeis

- Kullana Kulturali , Malta, published 1999 to 2006

Encyclopedias on the Internet

- h2g2 (humorous)

- Wikipedia

- See also: online lexicon

History of individual features

Classification systems

The form of alphabetical structuring of a printed encyclopedia, which prevailed from the 18th to the 20th century, is only one of numerous possibilities that have been used in its history. The following types of disposition for the classification and structuring of encyclopedias can be historically proven:

Miscellanees, collectans

Proto-encyclopedia and colored writing . Typical representatives: Aulus Gellius (around 150 AD): Noctes atticae; Peter Lauremberg (1590-1658): Acerra Philologica (1637); Erasmus Francisci ("Trawer Halls"); Georg Philipp Harsdörffer ("Schaw-Platz"); Eberhard W. Happel ("Worth knowing")

Systematic classification systems

Ever since the ancient times , there are systematically ordered encyclopedias. A disadvantage of this approach is that the user must already know enough about the topic to be able to find it in the right context. A detailed discussion of this can already be found in d'Alembert's Discours préliminaire de l'Encyclopédie of 1751 and in the entry “Encyclopédie” written by Diderot in the Encyclopédie .

For the numerous historical drafts of systematic orders see encyclopedia (knowledge order) .

Alphabetical classification systems

- Lists of persons that are not structured genealogically . Typical representatives: the prosopographic encyclopedias by Louis Moréri (1674) and Iselin (1726/7) [?]

- Semantic dictionaries from the ancient glossographic tradition. Typical representatives: Verrius Flaccus De significatu verborum ; Sextus Pompeius Festus (2nd half of the 2nd century AD); Isidore of Seville Book X of Etymologies ; Paul Deacon (8th century); Papias Elementarium (after 1053); Huguccio of Pisa; Guilemus Brito; Johannes Balbus ( Giovanni di Genoa , 1286)

- Distinctiones collections. Typical representatives: Eucherius von Lyon († 449) Formulas sprititalis intelligentiae ; Petrus Cantor († 1197) Summa quae dicitur Abel ; Petrus Berchorius († 1362) Repertorium morale

- Internal structure of larger chapter sections of systematically structured encyclopedias

- Alphabetical registers (since the late Middle Ages)

- Other early forms of the alphabetically structured encyclopedia are the Suda , the Promptus and the Polyanthea nova .

See also

- List of universal encyclopedias

- List of specialty encyclopedias

- List of dictionaries in German

- Reference book

literature

- Robert L. Collison: Encyclopaedias: their history throughout the ages: A bibliographical guide with extensive historical notes to the general encyclopaedias issued throughout the world from 350 BC to the present day. 2nd Edition. Hafner, New York 1966 (English).

- Hans-Joachim Diesner, Günter Gurst (Ed.): Lexica yesterday and today. VEB Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig 1976.

- Monika Estermann: Encyclopedias and Lexica. In: Hans Adolf Halbey (Hrsg.): Museum of books. (= The bibliophile paperbacks. Volume 500). Harenberg, Dortmund 1986, ISBN 3-88379-500-3 , pp. 316-353.

- FM Eybl et al. a. (Ed.): Encyclopedias of the early modern period. Contributions to their exploration. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1995.

- Harald Fuchs: Art. Encyclopedia . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 5. Stuttgart 1960, Col. 504-515.

- M. Fuhrmann: The European educational canon of the bourgeois age. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-458-16978-4 .

- Hans-Albrecht Koch (Ed.): Older conversation encyclopedias and specialist encyclopedias. Contributions to the history of knowledge transmission and mentality formation. (= Contributions to the history of text, transmission and education. Volume 1). Peter Lang GmbH, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2013, ISBN 978-3-631-62341-1 .

- Bernhard Kossmann: German universal lexica of the 18th century. Their essence and their informational value, illustrated using the example of the works of Jablonski and Zedler. In: Börsenblatt for the German book trade - Frankfurt edition. No. 89, November 5, 1968 (= Archive for the History of the Book Industry. Volume 62), pp. 2947–2968.

- Ernst Herbert Lehmann: History of the conversation lexicon. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1934.

- Werner Lenz (ed.): Small history of large encyclopedias. Bertelsmann-Lexikon-Verlag, Gütersloh et al. 1972, ISBN 3-570-03158-6 .

- Tom McArthur: Worlds of Reference: Lexicography, learning and language from the clay tablet to the computer. Cambridge 1986 (English).

- Anton Ernst Oskar Piltz: On the history and bibliography of the encyclopedic literature, especially the conversation lexicon. In: Heinrich Brockhaus (Hrsg.): Complete list of the works published by FA Brockhaus in Leipzig since it was founded by Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus in 1805 up to his centenary in 1872. In chronological order with biographical and literary-historical notes. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1872–1875, pp. I – LXXII ( digitized in the Internet Archive ).

- Anette Selg (ed.): The world of the Encyclopédie. Translated from the French by Holger Fock. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-8218-4711-5 .

- Ulrike Spree: The pursuit of knowledge - A comparative genre history of the popular encyclopedia in Germany and Great Britain in the 19th century. ( Communicatio, Volume 24). Niemeyer, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-484-63024-8 .

- Ingrid Tomkowiak (Ed.): Popular Encyclopedias. From the selection, order and transfer of knowledge. (= Memorial for Rudolf Schenda). Chronos Verlag, Zurich 2002, ISBN 3-03-400550-4 .

- Gert A. Zischka: Index lexicorum. Bibliography of Lexical Reference Works. Brothers Hollinek publishing house, Vienna 1959. (New print, Hollinek, Vienna 1980, ISBN 3-851-19165-X ).

Web links

- Margarete Rehm: Information and communication in the past and present (Humboldt University, Institute for Library Science)

- Research project general knowledge and society

- Encyclotheque. Historical reference works (digital library)

- Thomas Elyot : The Boke named The Governour (Old English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Carl Joachim Classen

- ↑ Harald Fuchs: Art. Encyclopedia . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Vol. 5, Stuttgart 1960, Col. 504.

- ↑ a b Book of Nature . August 20, 1481. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ↑ Collison p. 82 and texts by Francis Bacon in the University of Adelaide e-Library

- ^ Meyers Großes Taschenlexikon, Mannheim 2006.

- ↑ richardwolf.de

- ^ For digital copies, see Wikisource: Oesterreichische National-Encyklopädie

- ^ Catherine Santschi: Lexica. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 21, 2008 , accessed June 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Volume 1, in: Desertina, Chur 2010, ISBN 978-3-85637-390-0 and Volume 2: 2012, ISBN 978-3-85637-391-7 .

- ^ Jewish encyclopedia in the English language Wikipedia

- ↑ archive.org

- ↑ archive.org

- ↑ full Latin text