Graubünden Romance

| Romansh | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | approx. 60,000 (2000 census) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

rm |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

raw |

|

| ISO 639-3 | ||

The Grisons Romansh spoken in the Swiss canton of Graubünden - common Romansh or simply Romansh (own name: Rumantsch (Sutselvisch, Surmiran, Lower Engadine), Romontsch (Surselva), Rumauntsch (Upper Engadine)) - belongs together with the Dolomite Ladin and Friulian languages to the Romansh languages , a subgroup of the Romance languages . Whether the Romansh languages form a genetic unit - Graubünden Romansh is genetically more closely related to Dolomite Ladin and Friulian than to all other Romance languages - has not yet been decided in linguistic research (→ Questione Ladina ).

Romansh is the official language in the canton of Graubünden , along with German and Italian . At the federal level , it is the fourth national language of Switzerland alongside German, French and Italian ; It only has the status of an official language in dealings with Romansh-speaking residents.

designation

The relationship between Graubünden Romansh, Dolomite Ladin and Friulian is controversial in linguistics (more on this in the article Romansh languages ). The names are correspondingly inconsistent.

In Switzerland, the group of Romansh idioms spoken in Switzerland is mentioned in the federal constitution , in the constitution of the canton of Graubünden and in the laws of Romansh . The German-speaking Swiss also speak of Romansh or, more commonly, simply of Romansh . In contrast, linguists usually refer to the group of these idioms as Graubünden Romance . The term Romansh is used inconsistently by linguists and even rejected entirely by some.

The Graubünden Romanes themselves are also familiar with the use of different terms in parallel: the Societad Retorumantscha , founded in 1885, has “Rhaeto-Romanic”, the Dicziunari Rumantsch Grischun founded in 1904 “ Graubünden Romanian ” and the Lia Rumantscha founded in 1919 “Romansh”. The everyday self-name is, according to the German usage, simply rumantsch (or romontsch, rumauntsch ).

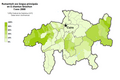

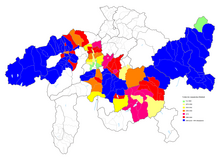

Distribution area

In the Swiss census of 1990, 66,356 people said Romansh was the regularly spoken language, 39,632 of which they named as their main language. In 2000, only 35,095 said Romansh was the main language.

Because of the former seclusion of many places and valleys in the canton of Graubünden, various dialects have developed that can be divided into five groups. Each of these five dialect groups has developed its own written language («idiom»), which in turn represents a compromise between different local and regional dialects .

- Sursilvan : widely spoken and written in the Vorderrheintal and its side valleys (in Tujetsch and Val Medel the subdialect Tuatschin is spoken), also only written in the Imboden (Il Plaun) region with the localities Domat / Ems , Rhäzüns (Razén), Bonaduz and Trin (the local dialects of the latter villages belong to the Sutsilvan)

- Sutsilvan : spoken and written in areas of the Hinterrhein , namely in the mountain communities of Domleschg (Tumleastga) and Heinzenberg (Mantogna), as well as in Schams (Schons) and in Val Ferrera , moreover only spoken in the Imboden region (see above)

- Surmiran : widely spoken and written in the Albula valley , in the municipality of Vaz / Obervaz and in Oberhalbstein (Sursès), also only spoken in Bergün / Bravuogn ( Bargunsegner )

- Putér : spoken and written in the Upper Engadine , only written in Bergün / Bravuogn, where a local dialect belonging to the Surmiran is spoken (see above)

- Vallader : widely spoken and written in the Lower Engadine , only written in the Münstertal , where Jauer is spoken

The alignment corresponds to the distribution from west to east. Putér and Vallader are also summarized in the novels as Rumantsch Ladin and sung about in the hymn Chara lingua da la mamma (chara lingua da la mamma, tü sonor rumantsch ladin ...) .

history

Originally, the current area of Grisons Romansh was inhabited by Celts and, presumably only in the very east of Graubünden, by Raetians . As to the assignment of the Raetians and their language, one is unsure. It is assumed, however, that the Rhaetian language was not Indo-European. More reliable statements can hardly be made because of the fragmentary tradition of the Rhaetian .

These peoples were born during the Alpine campaign of 15 BC. Subjugated by the Romans, who brought Latin (mainly in the form of spoken Vulgar Latin ) to the subject areas.

It is uncertain how quickly the romanization took place. At the end of antiquity, however, according to the not conclusive findings of linguistic research, the original pre-Roman languages had apparently practically died out, and only a few substring words remained in Romansh. These refer primarily to names typical of the Alps from the areas of flora and fauna as well as terrain names. From the Rhaetian z. B. (a) gnieu , AdlerHorst, Bird's Nest ' crap ' stone ', Grusaida , Alpenrose ', Izun , blueberry ', Schember , Zirbelkiefer ', tschess , Geier 'and urblauna , grouse '. From the Celtic z. B. carmun 'weasel', Engadin dischöl , döschel 'Albdruck, -traum', dratg , draig 'sieve', Upper Engadin giop 'juniper bush ', giutta 'barley, barley', glitta 'mud, silt', grava 'rubble, rubble dump ', marv ' stiff, frozen, limp ', mat ' young boy, lad '~ matta ' young girl ', mellen ' yellow ', tegia ' alpine hut ', trutg ' mountain path ', tschigrun ' Ziger 'and umblaz ' Yoke loop '.

From the 8th / 9th In the 19th century the region came under Germanic-speaking influence. In the further course, German increasingly became the official language, and at that time Graubünden Romance was viewed with contempt as a "peasant language". The fact that Graubünden Romansh was spoken in a much larger area in the past can be seen, among other things, from the many Graubünden Romanic place names and loan words in the German-speaking cantons of Glarus and St. Gallen . They show that up to the High Middle Ages and sometimes even longer the language border was in the northwest in the Gasterland and thus the entire Walensee area ( Walen- is related to Welsch ) was Romansh in the Grisons. In the northeast, the Romansh language area reached around 700 to Lake Constance and around 1100 to the so-called Hirschensprung near Rüthi in the St. Gallen Rhine Valley. Large areas in Vorarlberg and West Tyrol ( Oberinntal , Vinschgau ) were formerly Romanesque in Graubünden. Areas whose place names are not emphasized on the first syllable to this day were Germanized at the latest (after the 11th century), e.g. B. (Bad) Ragaz , Sargans , Vaduz (from Latin aquaeductus , water pipe '), Montafon , Tschagguns and Galtür .

The first known Romance language documents were translations of Latin sermons. The first known literary work is the song Chanzun da la guerra dal Chastè da Münsch, which was written in 1527 by the Engadin Gian Travers . The war for the Musso fortress on Lake Como in the years 1525–1526 is described in 700 verses ; the war went down in history as an idle war . It was only during the Reformation that actual written languages emerged in the various idioms. The main reason that no uniform written language developed for all idioms and that the Graubünden Romansh was increasingly losing ground to the German language was the lack of a Graubünden Romance intellectual and political center. The city of Chur , which was the only one that could have been considered for such a function, came under German influence as a bishopric early on and was only German-speaking from the 15th century. Only recently, i. H. from the beginning of the 20th century, as a result of the migration of novels to the capital, something like a center for the Romansh language and culture was able to develop here again, from which important impulses in the Romansh ancestral countries emanate. This development goes hand in hand with the increasing development of a Romance language awareness, which was largely absent before the 19th century.

The name Romansh was first coined in the late 19th century by the Romance scholar Theodor Gartner , where he used it in the title of his Rhaeto-Romanic grammar from 1883 and his handbook of the Rhaeto-Romanic language from 1913; from the beginning he referred to the entirety of the Romansh languages . The term takes on the name of the Roman province of Raetia , which, however, encompassed a much larger area than the habitat of the subjugated Raetians, who according to current research only lived in the far east of today's canton of Graubünden, namely in the Lower Engadine and in the Münstertal .

In the Middle Ages, German speakers called the Graubünden Romance Churwalsch, -welsch , d. H. " French language spoken by the inhabitants of Chur or the diocese of Chur ". In the 16th century, Martin Luther explicitly referred the word " gibberish " to "Churwelsch". The joking designation «Scree slope Latin» (for the geological background see Bündnerschiefer ) is more recent (mid-20th century) and is less contemptuous, but rather meant to be friendly or teasing.

Recent history

With the Italian unification of 1861 demands were made to incorporate all areas that were wholly or partly inhabited by an Italian-speaking population or that were south of the main Alpine ridge into the new Italian national state ( Italian irredentism ). This movement gained strength after the end of the First World War , when Italy did not get all of the territories that had been guaranteed to it in the London Treaty of 1915. This also affected Switzerland: the Italian Alpine valleys and the Rhaeto-Romanic areas in the cantons of Ticino and Graubünden were to fall to Italy. From the Italian side, Romansh was not understood as a separate language, but as a dialect of Lombard and thus linguistically part of Italy. A further intensification of the irredentist endeavors took place under the fascist government of Italy. On June 21, 1921, Benito Mussolini remarked in a speech that the state unification of Italy would not be complete until Ticino became part of Italy. The Rhaeto-Romanic minority was asserted that their linguistic and cultural peculiarities ran the risk of being ousted by a German-speaking majority and that the only protection against this "Pan-Germanism" was to be found in integration into the Italian Empire.

Italy's attempt to use irredentist propaganda to push a wedge between the linguistic majorities and minorities in Switzerland failed. Both Ticino and Rhaeto-Romans saw themselves as cultural Swiss and thus belonging to the Swiss nation-state. In order to put a stop to further influence from Italy once and for all, on February 20, 1938, the Romansh language was elevated to the fourth national language with a clear majority of 91.6%. In figures, 574,991 voters were in favor of a fourth national language, 52,827 voters were against. However, Romansh only achieved the status of an official language in dealings with Romansh-speaking residents through the referendum of 10 March 1996 on the revision of the language article of the Federal Constitution.

With the outbreak of the Second World War , the new status as the national language was immediately put to the test. As part of the censorship measures , only the four national languages were allowed for telecommunications in domestic traffic and the three official languages plus English for international traffic. However, this did not always go smoothly. It happened that telephone calls that were made in Romansh were interrupted by the telephone operators who were listening . Since these incidents were not isolated and thus the validity of the appointment as the national language was questioned, this led to a minor scandal. The matter gained momentum when the Romansh newspaper Fögl Ladin reported several times about such interruptions and even raised the question of whether it was even allowed to make calls in Romansh. This concern reached a climax when National Councilor Hans Konrad Sonderegger was interrupted in a personal conversation with his wife and was treated like a “foreign informant”. Thereupon National Councilor Sonderegger turned to the Federal Council on December 5, 1941 with a small request to ensure free telephone calls in Romansh in the future. The reasons for the interruptions in the Romansh phone calls were then easily found: Either there was a lack of staff who spoke the language sufficiently to be able to overhear if necessary, or the employees were not trained enough to even recognize Romansh as the fourth national language.

Recent retreat

After the language borders had remained relatively stable between the 15th and 18th centuries, Romansh has been increasingly challenged by German since the 19th century. Most of the Sutselvian area is now German-speaking; Young Romansh speakers can almost only be found there on Schamserberg . Romansh has also been on the defensive in the Upper Engadin since the end of the 19th century, but because of most places it has still held up a Romansh primary school significantly better than in Sutselva . In the Surmiran area, a distinction must be made between Sursès / Oberhalbstein and Albulatal: In Sursès, Romansh is still firmly anchored and not directly endangered, in contrast to the Albulatal. The strongholds of Romansh, on the other hand, can be found in the west and south-east of Graubünden: The Surselva (including the over 90% Romanesque side valley Lumnezia / Lugnez) and the Lower Engadine (including Münstertal ).

Rumantsch Grischun

Rumantsch Grischun (literally Graubünden Romance in German , not to be confused with Graubünden Romance ) is the common written language for the Rhaeto-Romanic idioms developed by the linguist Heinrich Schmid in the 1970s and 1980s on the initiative of the Lia Rumantscha . For this new standard language, a project team headed by Georges Darms developed a vocabulary that was published with the Pledari Grond lexicon . Rumantsch Grischun has been the official written language in the canton of Graubünden and in the federal government for communications with the Romansh-speaking population since 2001; in the Romansh communities, however, the respective idiom still serves as the official language. The common written language aims to strengthen Romansh and thus to preserve the threatened language.

Rumantsch Grischun was not only welcomed by the population in a friendly manner. Many people from Graubünden, and not just Romans, fear that an artificial language could become the grave digger of Romansh. Others are more optimistic and refer to the example of the written German language, which has not been able to significantly influence the diverse German-speaking Swiss dialects.

In August 2003, the Cantonal Parliament of Graubünden decided that Rumantsch Grischun should be introduced as a written language in all Romance schools and that new teaching materials for Romance-speaking schools would only be published in Rumantsch Grischun. Until then, all teaching materials were published in all five traditional idioms. On the one hand, this measure allows savings in the production of school books. Especially in heavily Germanized areas with a clearly different local idiom, however, it also weakens the position of Romansh, since the children de facto have to learn a second Romansh that is foreign to them. On the non-Romance side, the dialect differences are often underestimated, because they are much more pronounced than, for example, between the different German-speaking dialects. A transition period of twenty years applies to the implementation of the parliamentary resolution. According to the current legal situation, no municipality can later be forced to introduce Rumantsch Grischun at the school, but the procurement of suitable teaching materials in the idioms will become more and more difficult.

The Graubünden cantonal government has created various models for implementation. The model «pioneer community» sees z. E.g. the immediate introduction of Rumantsch Grischun in passive form, which means that the students learn Rumantsch Grischun only by listening to texts and songs during a two-year introductory phase. Rumantsch Grischun is only actively learned after this mandatory phase.

The municipalities of Val Müstair (Münstertal) were the first to opt for the pioneer model, and from 2005 the passive phase was under way in these municipalities. Since the 2007/2008 school year, the pupils of the Munster Valley have been actively learning Rumantsch Grischun as a written language. It is no coincidence that the municipalities of the Münstertal were the first to introduce Rumantsch Grischun as a written language, as the written language Vallader used so far already showed great differences to its own dialect; In addition, Romansh (in the form of the local dialect Jauer) is actively spoken and cultivated by 95 percent of the population, which means that Rumantsch Grischun is not perceived by the majority as a threat to their language. The proponents of Rumantsch Grischun see the loss of the old written language as outweighed by the advantage of a uniform written language throughout the canton.

In the meantime, other communities in the canton have followed the example of the Munster Valley, on the one hand in particular those in which dialects that are relatively close to Rumantsch Grischun are spoken, on the other hand those that are exposed to strong pressure from German. Most of the communities in Oberhalbstein, Albula and Lower Surselva (here first the community of Trin ) have also started and partially completed the "pioneering phase".

In the meantime, however, the parents of the children in Val Müstair see the idiom at risk and no longer consider Rumantsch Grischun helpful in promoting Romansh. In a vote in March 2012, they decided to have the idiom taught in schools again. Since then, Rumantsch Grischun has also been on the decline in some of the communities in the lower Surselva.

Anchoring Romansh in the Swiss constitutional context

At the federal level , Romansh is the national language and, in dealings with the Romansh-speaking population, it is the official language. Here all five idioms are equal. Romans thus have the opportunity and the right to communicate with the federal authorities in both language and writing in Romansh. However, federal publications are not written in the individual idioms, but exclusively in Rumantsch Grischun.

At the cantonal level , Romansh is one of the three cantonal national and official languages in Graubünden. Since 1992, the canton has used Rumantsch Grischun exclusively in correspondence with the Romansh population and in Romansh pronouncements (collection of laws, cantonal gazette, voting drafts, etc.). This practice is confirmed by Article 3 of the Grisons Language Act of 2006.

At the local level , each municipality regulates in its constitution and in its laws which language or which idiom is the official and / or school language. According to Article 16 of the Graubünden Language Act, municipalities in which at least 40% of the residents speak the ancestral idiom are officially monolingual, and municipalities in which at least 20 percent speak the ancestral idiom are officially bilingual. The municipalities also have the option of designating Rumantsch Grischun as the official language instead of a special idiom.

media

The radiotelevisiun svizra rumantscha , a subsidiary of the Swiss public media company SRG SSR , maintains the Radio Rumantsch and Televisiun Rumantscha .

Language training

The vocabulary of all Romansh dialects as well as that of the older language levels is documented in the multi-volume Dicziunari Rumantsch Grischun , which, published by the Società Retorumantscha , has been published in Chur since 1938. We are currently working on the 14th volume.

The Lia Rumantscha is the umbrella organization of various regional associations, the competent authority for Grison Romanesque cultural and language support, for which it is largely funded by the federal and cantonal.

The Lia Rumantscha and the regional associations belonging to it were restructured between 2005 and 2007; the competencies were divided according to territory, denominations are no longer relevant.

|

|

The most important Romansh youth organization is the Giuventetgna Rumantscha (GiuRu), which is also the publisher of the youth magazine PUNTS, whose publication was discontinued at the end of 2011 due to a lack of young people to produce the texts.

There are also a few other associations that are also committed to promoting Romansh in the Graubünden, but operate independently of the Lia Rumantscha. This includes:

- Pro Rumantsch , a manifesto that aims to introduce Rumantsch grischun as a literacy language in schools.

- Pro Idioms , association for the preservation of Graubünden Romance dialects in compulsory schools.

- viro, Visiun Romontscha , an association from the Surselva, which wants to publish a "Cudischet" for each community, in which the respective community is presented in Graubünden Romance.

- Pro Svizra Rumantscha , who campaigned for a supraregional Graubünden Romance daily newspaper and now supports the Romance news agency ANR (Agency da Novitads Rumantscha ).

- Raetia , an association in German-speaking Switzerland, with the aim of making the Romansh language known there.

- Romontschissimo , an association from the Surselva, which has set itself the goal of developing learning software for Romansh in the Grisons.

The American software manufacturer Microsoft also made a contribution to the spread of Rumantsch Grischun as the common written language of the Graubünden Romance dialects in spring 2006 with the Graubünden Romance translation of Microsoft Office with a corresponding dictionary and grammar check. Since April 2005, Google Inc. has been offering a Romansh surface for its search service.

Linguistic peculiarities

The ending "-ziun" or letter combinations such as "tg" or "aun" / "eun", which are alien to neighboring Italian, are typical of the Romansh language . Probably the most striking distinguishing feature to this is the plural formation with -ls or -s , which does not exist in Italian.

In most of the idioms the phonetic connection [ʃc] / [ʃtɕ] can be found; The spelling s-ch (for example s-chela 'stairs', suos-ch 'dirty' and often in place names: S-chanf , S-charl, Chamues-ch , Porta d'Es-cha) is particularly striking in the Engadine ). In the other idioms the same sound is written stg (for example, surselvian biestg 'cattle').

Magazines

- Engadiner Post (Posta Ladina), bilingual weekly newspaper for the Engadin

- La Pagina da Surmeir , Romance weekly newspaper for the Oberhalbstein (= Surses)

- La Quotidiana , Romansh daily newspaper for all Romansh-speaking areas

Comparison of the Romansh idioms

The differences between the idioms are illustrated here using the example of the first sentences of the fable "The Raven and the Fox" by Jean de La Fontaine :

Surselvian (Sursilvan)

L'uolp era puspei inagada fomentada. Cheu ha ella viu sin in pegn in tgaper che teneva in toc caschiel en siu bec. Quei gustass a mi, ha ella tertgau, ed ha clamau al tgaper: “Tgei bi che ti ice! Sche tiu cant ei aschi bials sco tia cumparsa, lu eis ti il pli bi utschi da tuts ».

Sutselvian (Sutsilvan)

La gualp eara puspe egn'eada fumantada. Qua â ella vieu sen egn pegn egn corv ca taneva egn toc caschiel ainten sieus pecel. Quegl gustass a mei, â ella tartgieu, ad â clamo agli corv: «Tge beal ca tei es! Scha tieus tgànt e aschi beal sco tia pareta, alura es tei igl ple beal utschi da tuts ».

Surmeirian (Surmiran)

La golp era puspe eneda famantada. Cò ò ella via sen en pegn en corv tgi tigniva en toc caschiel ainten sies pechel. Chegl am gustess, ò ella panso, ed ò clamo agl corv: “Tge bel tgi te is! Schi igl ties cant è schi bel scu tia parentscha, alloura is te igl pi bel utschel da tots ».

Upper Engadin (turkey)

La vuolp d'eira darcho üna vouta famanteda. Cò ho'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tgnaiva ün töch chaschöl in sieupical. Que am gustess, ho'la penso, ed ho clamo al corv: «Che bel cha tü est! Scha tieu chaunt es uschè bel scu tia apparentscha, alura est tü il pü bel utschè da tuots ».

Lower Engadine (Vallader)

La vuolp d'eira darcheu üna jada fomantada. Qua ha'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tgnaiva ün toc chaschöl in seis pical. Quai am gustess, ha'la pensà, ed ha clomà al corv: «Che bel cha tü est! Scha teis chant es uschè bel sco tia apparentscha, lura est tü il plü bel utschè da tuots ».

Jauer (Münstertal)

La uolp d'era darchiau üna jada fomantada. Qua ha'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tegnea ün toc chaschöl in ses pical. Quai ma gustess, ha'la s'impissà, ed ha clomà al corv: «Cha bel cha tü esch! Scha tes chaunt es ischè bel sco tia apparentscha, lura esch tü il pü bel utschè da tots ».

(Since the Jauer does not have its own standardized written language, this is only an example of how to reproduce the dialect in writing.)

Rumantsch Grischun

La vulp era puspè ina giada fomentada. Qua ha ella vis sin in pign in corv che tegneva in toc chaschiel en ses pichel. Quai ma gustass, ha ella pensà, ed ha clamà al corv: “Everyday bel che ti es! Sche tes chant è uschè bel sco tia parita, lura es ti il pli bel utschè da tuts ».

Italian

La volpe era di nuovo affamata. Vide allora su un abete un corvo che teneva un pezzo di formaggio nel becco. Quello mi piacerebbe, pensò, e gridò al corvo: «Che bello be! Se il tuo canto è so bello come il tuo aspetto, allora be il più bello di tutti gli uccelli ».

Latin

Cum vulpes rursus esuriebat, subito vidit corvum abiete residentem et caseum in ore tenentem. Cum hunc sibi dulci sapore fore secum cogitavisset, clamavit ad corvum: «Quam pulcher es! Cum tibi cantus aeque pulcher est atque species, tum es pulcherrimus omnium alitum ».

German

The fox was hungry again. Then he saw a raven on a fir tree with a piece of cheese in its beak. I would like that, he thought, and called to the raven: “How beautiful you are! If your song is as beautiful as your looks, then you are the most beautiful of all birds ».

See also

- Dicziunari Rumantsch Grischun

- Grammar of Rumantsch Grischun , grammar of the common written Rhaeto-Romanic language

- Lia Rumantscha

- Romansh

- List of Romansh names of Swiss places

- Pledari Grond

- Societad Retorumantscha

literature

- Jachen Curdin Arquint, Werner Carigiet, Ricarda Liver: The Rhaeto-Romanic Switzerland. In: Hans Bickel , Robert Schläpfer (ed.): The four-language Switzerland (= series Sprachlandschaft. Volume 25). 2nd, revised edition. Sauerländer, Aarau / Frankfurt am Main / Salzburg 2000, ISBN 3-7941-3696-9 , pp. 211-267 (Ricarda Liver: Das Bündnerromanische; Werner Carigiet: Zur Mehrsprachigkeit der Bündnerromanen; Jachen Curdin Arquint: Stations of Standardization ).

- Michele Badilatti: The time-honored language of mercenaries and peasants - The refinement of Graubünden Romance by Joseph Planta (1744–1827) (= Swiss Academies Reports. Volume 12 [6], 2017; both languages and cultures. Volume 9). Edited by the Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences. Bern 2017, ISSN 2297-1564 and ISSN 2297-1572 ( PDF; 1.1 MB ).

- Robert H. Billigmeier, Iso Camartin (Vorw.): Land and people of the Rhaeto-Romans. A history of culture and language. Translated and reviewed by Werner Morlang , with assistance from Cornelia Echte. Huber, Frauenfeld 1983, ISBN 3-7193-0882-0 .

- Original edition: A crisis in Swiss pluralism (= Contributions to the sociology of language. Vol. 26). Mouton, 's-Gravenhage / The Hague 1979, ISBN 90-279-7577-9 .

- Renzo Caduff, Uorschla N. Caprez, Georges Darms : Grammatica per l'instrucziun dal rumantsch grischun. Corrected version. Seminari da rumantsch da l'Universitad da Friburg, Freiburg 2009, OCLC 887708988 , pp. 16-18: Pronunciation and emphasis ( PDF; 726 kB ).

- Werner Catrina : The Rhaeto-Romanic between resignation and departure. Orell Füssli-Verlag, Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-280-01345-3 .

- Dieter Fringeli : World of ancient customs. The bitter homeland of the Romansh. On the Romansh literature in Switzerland. In: Nicolai Riedel, Stefan Rammer u. a. (Ed.): Literature from Switzerland. Special issue from Passauer Pegasus. Journal of Literature. Issue 21-22, 11th year Krieg, Passau 1993, ISSN 0724-0708 , pp. 353-357.

- Hans Goebl : 67. External language history of the Romance languages in the Central and Eastern Alps. In: Gerhard Ernst, Martin-Dietrich Gleßgen, Christian Schmitt, Wolfgang Schweickard (eds.): Romanische Sprachgeschichte / Histoire linguistique de la Romania. An international handbook on the history of Romance languages / Manuel international d'histoire linguistique de la Romania (= Herbert Ernst Wiegand [Ed.]: Handbooks for Linguistics and Communication Studies. Volume 23.1). 1st subband. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-014694-0 , pp. 747-773, here: pp. 749-755 ( PDF; 544 kB ; basic).

- Joachim Grzega : Romania Gallica Cisalpina. Etymological-geolinguistic studies on the Northern Italian-Rhaeto-Romanic Celticisms (= supplements to the magazine for Romance philology . Vol. 311). Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 978-3-484-52311-1 (Zugl .: Eichstätt, Kath. Univ., Diss.); Reprint: De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-094440-2 , urn : nbn: de: 101: 1-2016072616966 ( preview in Google book search).

-

Günter Holtus , Michael Metzeltin , Christian Schmitt (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Romance Linguistics . 12 volumes. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1988-2005; Volume III: The individual Romance languages and language areas from the Renaissance to the present. Romanian, Dalmatian / Istra Romansh , Friulian, Ladin, Grisons Romansh. 1989, pp. 764-912, ISBN 3-484-50250-9 .

- Helmut Stimm / Karl Peter Linder: Internal Language History I. Grammar. Pp. 764-785.

- Ricarda Liver : Internal History of Language II. Lexic. Pp. 786-803.

- Hans Stricker: Internal Language History III. Onomastics. Pp. 804-812.

- Andres Max Kristol : Sociolinguistics. Pp. 813-826.

- Georges Darms: Language standardization and standard language. Pp. 827-853.

- Günter Holtus: External Language History. Pp. 854-871.

- Theodor Ebneter: Area Linguistics. Pp. 871-885.

- Florentin Lutz: Grammarography and Lexicography. Pp. 886-912.

- Gion Lechmann: Romansh language movement. The history of the Lia Rumantscha from 1919 to 1996 (= studies on contemporary history. Vol. 6). Huber, Frauenfeld 2005, ISBN 3-7193-1370-0 .

- Ricarda Liver: Romansh. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Ricarda Liver: Romansh - An introduction to Romansh in Grisons . Gunter Narr, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-8233-4973-2 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- Ricarda Liver: The vocabulary of the Bünderromanischen. Elements of a Rhaeto-Romanic lexicology. Francke Verlag, Bern 2012, ISBN 978-3-7720-8468-3 .

- Peter Masüger: From Old Rhaeto-Romanic to “Tschalfiggerisch”. In: Terra Grischuna . 48/1, 1990, ISSN 1011-5196 .

- Walther von Wartburg : The origin of the Rhaeto-Romanic and its validity in the country. In: Walther von Wartburg: Of language and people. Collected Essays. Francke, Bern [1956], pp. 23-44.

- Uriel Weinreich : Languages in Contact. French, German and Romansh in twentieth-century Switzerland. With an introduction and notes by Ronald I. Kim and William Labov. John Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia 2011, ISBN 978-90-272-1187-3 (slightly revised edition of the dissertation from 1951, in which pp. 191-324 on Graubünden Romance).

Web links

- Homepage of the Lia Rumantscha

- Romansh - Facts & Figures ( Memento of October 10, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.42 MB; version “d”, May 2, 2006, 11:07:09; for a later version, see the individual references to the section Die Bündnerromanischen Idioms in comparison )

- Dicziunari Rumantsch Grischun

- Kuno Widmer: The Origin of the Romance Idioms of Graubünden. (PDF; 75 kB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 31, 2012 .

- Peter Justus Andeer: About the origin and history of the Rhaeto-Romance language. Chur 1862

- Radio e Televisiun Rumantscha RTR

- Giuventetgna Rumantscha

- PSR - Pro Svizra Rumantscha

- chattà.ch - Texts and other materials in Rumantsch Grischun

- Pro idioms

- viro - Visiun Romontscha (Surselva) ( Memento from March 26, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- pledarigrond.ch Very extensive online dictionary Romansh↔German , only Rumantsch Grischun

- pledari.ch online dictionary Romansh↔English, Romansh↔German, Romansh↔Italian, Romansh↔French , with all five written languages and Rumantsch Grischun

- romontsch.ch language learning programs - very extensive vocabulary trainer

- Jörg Krummenacher: Change of opinion in the Münstertal. The pioneer community decides whether to abandon Rumantsch Grischun as the school language. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . Online report in nzz.ch. March 2, 2012 (article on the exit of the Val Müstair from Rumantsch Grischun)

- Dario Widmer. (No longer available online.) In: dariowidmer.ch. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016 (Romanesque musician , songwriter and music producer from the Lower Engadine).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Furer: The current situation of the Romanesque . Swiss Federal Census 2000. Ed .: Federal Statistical Office (= Swiss Statistics . Department 1 Population). Neuchâtel 2005, ISBN 3-303-01202-4 ( bfs.admin.ch [PDF; 3.3 MB ; accessed on June 17, 2018] online edition from December 14, 2005, amended on January 11, 2006).

- ↑ a b So also in Article 4 of the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation and in Article 3 of the Constitution of the Canton of Graubünden.

- ^ Arnold Spescha: Grammatica Sursilvana. Casa editura per mieds d'instrucziun, Chur 1989, p. 44.

- ^ Georg Bossong: The Romance Languages. A comparative introduction. Buske, Hamburg 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ Schweizerisches Idiotikon , Volume XV, Column 1601, Article churwälsch ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Oscar Alig: Irredentism and the Rhaeto-Romanic . In: Eduard Fueter, Paul Flückiger, Leza Uffer (eds.): Swiss university newspaper . tape 6 . Gebr. Leemann, Zurich February 1938, OCLC 83846644 , p. 341-349 .

- ^ Federal Council Message of June 1, 1937 ( PDF ); Debate in the Council of States on December 5, 1937 ( PDF ); Debate in the National Council on December 6, 1937 ( PDF ) and December 7, 1937 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Referendum of February 20, 1938. In: admin.ch. Retrieved May 24, 2017 .

- ^ Arnold Spescha: Grammatica Sursilvana. Casa editura per mieds d'instrucziun, Chur 1989, p. 47.

- ↑ Swiss National Library NL: Official and national languages of Switzerland. (No longer available online.) In: nb.admin.ch. August 3, 2013, archived from the original on November 8, 2016 ; accessed on May 24, 2017 .

- ↑ Orders, directives, instructions on the implementation and organization of telegram and telephone censorship in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives .

- ↑ Hans Konrad Sonderegger: Do not telephone in Romansh! In: Volksstimme St. Gallen . November 13, 1941.

- ^ Georges Darms , Anna-Alice Dazzi: Basic work on the creation of a Rhaeto-Romanic written language (Rumantsch Grischun). Swiss National Fund for the Promotion of Scientific Research , Annual Report 1984, pp. 188–194.

- ↑ Article 4 and Article 70 of the Federal Constitution of April 18, 1999.

- ^ Constitution of the Canton of Graubünden from May 18, 2003.

- ↑ a b Language Law of the Canton of Graubünden of October 19, 2006 (PDF; 274 kB).

- ↑ Download details: Office 2003 Romansh Interface Pack . microsoft.com. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ a b All examples (except Italian, Latin, German) are taken from: Lia Rumantscha (Ed.): Rumantsch - Facts & Figures. From the German by Daniel Telli. 2nd, revised and updated edition. Chur 2004, ISBN 3-03900-033-0 , p. 31, PDF; 3.5 MB ( Memento from May 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 6, 2016 (version “r”, May 2, 2006, 11:15:24 am).