Surselvic language

Surselvisch (also Oberlandisch, Oberwaldisch, Romansh Sursilvan ) is a Graubünden Romanesque idiom and is spoken in the Surselva region in the canton of Graubünden , i.e. in the Vorderrheintal from Flims / Flem up the valley. The next related idiom is Sutsilvan , which adjoins to the east .

Tuachin is a subdialect of Sursilvan with some peculiarities .

Spreading the language

According to the census in 2000, 13,879 people in the then Surselva district stated that Sursilvan was their mother tongue and the language they knew best. This corresponds to a share of 42.5% of the total population. 17 897 people stated that they use the language in everyday life, in the family and at work, which corresponds to 54.8% of the total population. In Val Lumnezia , 82% of the population said that Sursilvan was the language they mastered most; in the Cadi this was 78.1%, in the Gruob 48%, in the city of Ilanz, however, only 29.9%.

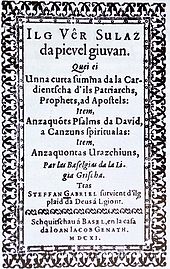

First prints

After the Reformation , the need for a written language in Graubünden Romance grew; the Romance reformers wanted to translate the Bible and other theological writings into the language of the people. After Durich Campell 1562 Psalm translations Ün Cudesch as Psalms in Engadinerromanisch had written the first book was published in 1611 Sursilvan of Ilanzer pastor Stefan Gabriel in Basel : Ilg Ver sulaz since pievel giuvan ( "The real entertainment of the young people").

Linguistic features at a glance

Phonology

In contrast to the idioms in the Engadine , which still know the rounded front tongue vowels / ü / and / ö /, in Surselvian rounding to / i / and / e / took place, compare Surselvian to me "Mauer", egl "Auge" with Engadin mür , ogl . Surselvian (with the exception of the Tujetsch dialect) then knows no palatalization of the initial / k / to / tsch / before / a /, compare Surselvian casa "house" with / k / compared to sutselvian tgea, Vallader (Upper Engadin) chasa and Puter ( Lower Engadin) chesa, all of which are pronounced with / ch /.

morphology

A unique selling point of Surselvic compared to the other Romansh idioms in the area of inflection forms is that a predicative, i.e. subsequent adjective, has a special masculine ending on -s : il Pieder Fluretg, maghers e secs "Pieder Fluretg, mager und dürr". Another morphological unique selling point within the Bündner Romania is that the occurrence of clitic subject pronouns in Surselvic is limited to a few cases; In other words, the pronoun following the verb is often shortened in Engadin and Central Grisons, much less often in Surselvian.

syntax

A differentiation in the sentence structure is that in Engadin a direct object is introduced with the preposition a , but not in Surselvian, compare Surselvisch has viu Peider? "Did you see Peter?" with turkey hest vis a Peider?

Other uncommon or rare occurrences in Romania, such as the use of the subjunctive in indirect speech or the reversal of the sequence subject - verb after the preceding adverb , adverbial definition or subordinate clause, are common to all Graubünden Romance idioms. They were borrowed from the German language, which is ubiquitous in Graubünden, or from Swiss German.

orthography

In the spelling in Surselvic - apart from in foreign words - hardly any accented characters are used: The è "is" in Rumantsch Grischun corresponds to ei in Surselvic . For this you need the letter h in Surselvic : The istorgia "Geschichte" in Rumantsch Grischun corresponds to Surselvic historia . The verb "haben", which is written in Rumantsch Grischun avair , is written in Surselvian haver .

pronunciation

The stress is usually on the penultimate or last syllable. In unstressed syllables, the vowels usually turn into a mumbled e ( Schwa ). In the following, those pronunciations are listed that might be unclear for a German speaker.

|

grammar

Noun, gender, article

Surselvian knows definite and indefinite articles, but indefinite only in the singular. There are two grammatical genders: nouns can be masculine or feminine. Female nouns often end in -a . Basically, the majority of a noun is formed by adding an -s . If the noun ends in -s, the noun remains unchanged.

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| a house | ina chasa | ina casa |

| a village | in vitg | in vitg |

| the House | la chasa | la casa |

| a car | l'auto | l'auto |

| the houses | las chasas | las casas |

| the village | il vitg | il vitg |

| the villages | ils vitgs | ils Vitgs |

| the cars | ils cars | ils cars |

In Sursilvan, prepositions and certain articles are pulled together as in Italian. In Rumantsch Grischun, however, not.

| Preposition | German | il | igl | ils | la | l ' | read |

| a | on | al | like | as | alla | Alles' | all |

| cun | With | cul | cugl | culs | culla | cull ' | cullas |

| there | from | dil | digl | dals | dalla | dall ' | dallas |

| en | in | el | egl | els | ella | ell ' | ellas |

| by | For | pil | pigl | pils | per la | per l ' | per read |

| sin | on | sil | sigl | sils | silla | sill ' | sillas |

| animal | at | tiel | deeply | tiels | tiella | tiell ' | tiellas |

adjective

Adjectives are usually followed by the noun and, like this, inflected according to gender and number - a masculine noun is followed by a masculine inflected, a feminine noun is followed by a feminine inflected, and a noun in the plural is followed by an adjective in the plural. In the case of essential properties, however, the adjective comes before the noun. So if a property describes a thing, then the adjective comes after the noun, if the property is significant for the sense of the noun, the adjective comes before the noun.

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| a big house | ina gronda chasa | ina gronda casa |

| a big village | in grond vitg | in grond vitg |

| a big (important) man | in green around | in green around |

| A (physically) great man | in around grond | In around grond |

| an important woman | ina dunna gronda | ina dunna gronda |

| an important women | las grondas dunnas | las grondas dunnas |

| the (financially) poor woman | la dunna paupra | la dunna paupra |

| the deplorable men | ils paupers ums | ils paupers ums |

| a big white house | ina gronda chasa alv | ina gronda casa alv |

verb

The improver "to be" is inflected in the present as follows:

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| I am | yeah sun | jeu sun |

| you are | ti it | ti ice |

| he is | el è | el egg |

| she is | ella è | ella egg |

| it is | in è | into egg |

| we are | nut essan | nut essan |

| you are | vus essas | vus essas |

| they are (male) | els èn | els a |

| they are (female) | ellas èn | ellas a |

The verb haver "haben" (Rumantsch Grischun: avair ) is inflected in the present as follows:

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| I have | yeah shark | jeu hai / jeu vai |

| you have | ti has | ti has |

| he has | el ha | el ha |

| she has | ella ha | ella ha |

| it has | in the ha | in the ha |

| we have | nus avain | nus vein |

| do you have | vus avais | vus veis |

| they have (male) | els han | els han |

| they have (female) | ellas han | ellas han |

Sentence structure

As in German, simple questions are formed by reversing the word sequence (inversion), i.e. the sequence noun - verb of the statement is replaced by the sequence verb - noun:

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| He is German. | El è tudestg. | El ei tudestg. |

| Is he german? | È el tudestg? | Ei el tudestg? |

Numbers up to 10

| German | Rumantsch Grischun | Romontsch Sursilvan |

| zero | nulla | nul, nulla |

| one | in, ina | in, ina |

| two | dus, duas | dus, duas |

| three | trais, treia | treis, trei |

| four | quatter | quater |

| five | Tschintg | Tschun |

| six | sis | sis |

| seven | set | siat |

| eight | otg | otg |

| nine | nov | nov |

| ten | this | this |

Language example

The following language example comes from Jean de La Fontaine's fable “The Raven and the Fox”. The Lia Rumantscha first mentioned it in 2004 in its Rhaeto- Romanic brochure . Facts and Figures published for the first time; it is often used to illustrate the differences between the various Romansh idioms. An audio version of the Sursilvian version can

be heard.

Surselvian L'uolp era puspei inagada fomentada. Cheu ha ella viu sin in pégn in tgaper che teneva in toc caschiel en siu bec. Quei gustass a mi, ha ella tertgau, ed ha clamau al tgaper: “Tgei bi che ti ice! Sche tiu cant ei aschi bials sco tia cumparsa, lu eis ti il pli bi utschi da tuts. "

Rumantsch Grischun La vulp era puspè ina giada fomentada. Qua ha ella vis sin in pign in corv che tegneva in toc chaschiel en ses pichel. Quai ma gustass, ha ella pensà, ed ha clamà al corv: “Everyday bel che ti es! Sche tes chant è uschè bel sco tia parita, lura es ti il pli bel utschè da tuts. "

German The fox was hungry again. Then he saw a raven on a fir tree with a piece of cheese in its beak. I would like that, he thought, and called to the raven: “How beautiful you are! If your singing is as beautiful as your looks, then you are the most beautiful of all birds. "

literature

- Ricarda Liver : Romansh. An introduction to the Romansh language of the Grisons. Gunter Narr, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-8233-4973-2 (focused on the Surselvic).

- Gereon Janzing: Romansh word for word (Surselvisch, Rumantsch, Bündnerromanisch, Surselvan). (= Gibberish. Volume 197). 4th edition. Reise Know-How Verlag Peter Rump, Bielefeld 2006, ISBN 3-89416-365-8 (despite the title deals almost exclusively with survival).

- Alexi Decurtins: Niev vocabulari romontsch sursilvan - tudestg / New Rhaeto-Romanic dictionary surselvian - german. Cadonau, Chur 2001, ISBN 3-03900-999-0 .

- Ramun Vieli, Alexi Decurtins: Vocabulari tudestg - romontsch-sursilvan. 5th edition. Lia Rumantscha, Chur 1995, OCLC 793586703 .

- Arnold Spescha: Grammatica sursilvana. Casa editura per mieds d'instrucziun / Lehrmittelverlag Graubünden, Chuera / Chur 1989, OCLC 77992907 (this grammar is written entirely in Romansh and does not contain any German explanations).

- En lingia directa. In cuors da romontsch sursilvan. Two volumes. Lia Rumantscha, Chur 2018, ISBN 978-3-03900-150-7 and ISBN 978-3-03900-152-1 .

- Gion Deplazes : Funtaunas. Istorgia da la literatura rumantscha per scola a pievel. 4 volumes. Lia Rumantscha, Chur 1987; 2nd updated edition, ibid. 1993/2011, OCLC 749433263 , ISBN 3-03900-005-5 , ISBN 3-03900-006-3 , ISBN 3-906680-19-3 .

Beautiful literature in Surselvian is published by the Lia Rumantscha in Chur , among others .

Web links

- www.vocabularisursilvan.ch Online version of the Niev vocabulari romontsch sursilvan - tudestg with search options in both directions (full text search).

Individual evidence

- ^ Association Romontschissimo

- ↑ a b c d After Ricarda Liver: Romansh. An introduction to the Romansh language of the Grisons. Gunter Narr, Tübingen 1999.

- ↑ Rico Cathomas: School and bilingualism. Waxmann, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8309-1575-6 , p. 145.

- ↑ Saving Romansh with referendums? On: www.swissinfo.ch.