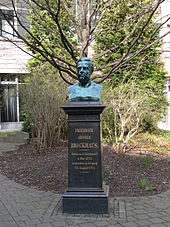

Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus

Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (born May 4, 1772 in Dortmund ; † August 20, 1823 in Leipzig ) was a German publisher , founder of the publishing house " F. A. Brockhaus " and editor of the Conversations Lexicon , which appeared in multiple editions and numerous reprints during his lifetime , the later Brockhaus encyclopedia .

In addition to his encyclopaedic activities, he mainly emerged as a publisher of political and time-critical, but also literary-critical journals and came into conflict with the censorship several times. In his own contributions he acted both as a reporter - for example from the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig in October 1813 - and as a critical commentator on the political circumstances of the time.

In the field of monographs, his publishing focus was on contemporary history, politics and history as well as biographical portraits. In addition, in 1818 he published the main work of the then almost unknown philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and from 1821 the then fiercely controversial memoirs (" Histoire de ma vie ") by the Venetian adventurer Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798).

After his death the publishing house was continued by his two sons Friedrich and Heinrich .

life and work

Dortmund

Origin, youth and education

Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus was born in Dortmund in 1772 as the son of the merchant and councilor Johann Adolf Heinrich Brockhaus (* May 21, 1739 in Meyerich, today in Welver ; † March 26, 1811) . His father came from a Westphalian pastor family and was the first to devote himself not to the theological but to the commercial profession. After completing an apprenticeship in Hamm, he founded a retail trade for "Ellens and Spice Goods" in Dortmund, where in 1767 he met Katharina Elisabeth Davidis (* March 22, 1736; † August 15, 1789), the widow of the doctor Dr. Kirchhoff, married. Just like his older brother Gottlieb (* September 4, 1768; † May 30, 1828), who later took over his parents' business, Friedrich Arnold should take up the commercial profession. Therefore, at the request of his father, he prematurely ended his attendance at Dortmund grammar school at the age of sixteen and began a commercial apprenticeship with Friedrich Christian Hoffmann in Düsseldorf . However, this activity did not fill him, because Brockhaus was very enthusiastic about reading from his earliest youth - in a biographical work printed by Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus he himself speaks of a “true book madness” - and had shown little interest in temporary work in his father's company. After a dispute with his principal Brockhaus, who was known throughout his life for his quick temper, broke off his apprenticeship in Düsseldorf and returned to Dortmund in 1793.

Study visit to Leipzig and start of business activity

After his return home, he finally prevailed over his father and began a year and a half of study in Leipzig . With no university entrance qualification, he took part in lectures as a guest auditor and heard, among others, philosophy from Ernst Platner , physics and mathematics from Carl Friedrich Hindenburg and chemistry from Christian Gotthold Eschenbach (1753–1831). He also got to know the busy bookselling and literary life of the trade fair city of Leipzig. At the end of 1794 he returned to Dortmund and on September 15, 1796, together with two business partners, founded their own company called "Brockhaus, Mallinckrodt and Hiltrop", specializing in the trade in English manufactured goods - especially coarse woolen fabrics. Almost three years later the business was financially so secure that he was able to marry Sophie Wilhelmine Arnoldine Beurhaus, the daughter of the highly respected Dortmund senator and professor Johann Friedrich Beurhaus. In the same year Brockhaus and Mallinckrodt separated from Hiltrop, paid him his share and renamed themselves "Brockhaus and Mallinckrodt". Since the two business partners carried out their imports of uniform fabrics, which were particularly in demand at the time, via the Batavian Republic , they founded a second trading house in Arnhem , the Netherlands , which Mallinckrodt took over.

Dispute with Hiltrop and departure from Dortmund

After a falling out with his former Dortmund business partner Hiltrop, Brockhaus went to the Netherlands in late autumn 1801. The cause of this dispute lay in the collapse of the London banking house Bethmann in October 1799, with which both Brockhaus & Mallinckrodt and Hiltrop had operated bills of exchange. The dispute over mutual liabilities finally culminated in the confiscation of Brockhaus & Mallinckrodt's warehouse in Dortmund at the instigation of Hiltrop, who was only persuaded to give in through the mediation of Hiltrop's wife, a sister of Brockhaus' wife. When the dispute flared up again in the summer of 1801 and Brockhaus was even briefly arrested at Hiltrop's instigation, he fled Dortmund and moved to Arnhem .

Amsterdam

New beginning in Amsterdam; 1804 crisis

However, Brockhaus did not stay long in Arnhem. In addition to Hamburg, the large trading metropolis of Amsterdam was the gateway for English goods to Europe and thus offered Brockhaus much greater entrepreneurial opportunities. So he separated from Mallinckrodt and moved to the Amstel estuary in the winter of 1801/1802. The new beginning there was initially difficult, as his creditworthiness had suffered severely as a result of the lawsuit against Hiltrop. But with the support of his brother Gottlieb and with the capital of several French emigrants, Brockhaus succeeded in re-entering the wholesale trade with English manufactured goods.

But obviously he had speculated, because on September 30, 1804 he wrote in a letter of appeal to his brother:

“Unfortunately, I have still not learned the golden art of hoisting sails when the wind is most beneficial. Seduced by the cheap deal this year, I unfortunately plunged too deep into it again, and as a result I got knocked over my head. […] The lesson I am now receiving was sharp: my existence was written on the tip of a pin - I received it - but my credit has suffered deeply and it is more difficult to replace it, even though I don't need any special credits right here on the spot . For I have sacredly vowed to myself, my dear wife and my beloved children: from now on I will only want to have a small business that is only half the size of my current one. "

In this situation, he decided to give up his extensive business in English goods and start a bookstore.

Foundation of the bookstore "Rohloff & Co."

In the summer of 1805 his plans slowly took shape and on October 15, 1805 Brockhaus sent out his first business circular , in which he announced the establishment of his Amsterdam bookstore. This date is now considered to be the founding day of the publishing house “FA Brockhaus” (until 2009: Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus ). Since Brockhaus was denied membership in the Amsterdam Booksellers Guild as a foreigner, he ran the business in the name of the printer JG Rohloff as "Rohloff and Compagnie", for which Rohloff received a small compensation. Just two years later Brockhaus let the name Rohloff disappear completely and renamed his company to “Art and Industry Comtoir”, according to his own statement, “not to let the shadow of anxiety arise in the soul of the good man, which he does have had to because his name was used ”. It is no longer possible to determine clearly what position Brockhaus occupied in the early stages of the company. On the one hand, he wrote in a letter to his brother dated August 26, 1805, “We have a main director and I am a secondary director”, on the other hand, in a later letter to Gottlieb dated August 25, 1807, he claims that he is been the sole owner “of the Rohloff & Co. company. What is certain is that over the years his activities as a bookseller and publisher took on more space than his other commercial business. The difficulties that the Napoleonic continental barrier imposed on European trade since 1806 will have played a not inconsiderable part here.

First publishing activity

In addition to his work as a general-purpose bookseller, Brockhaus also devoted himself to the publishing business from the start. In quick succession he founded the Dutch-language political-literary newspaper De Ster (Eng. "Der Stern"), the German contemporary historical monthly Individualitäten aus and über Paris , for which he was his first author with Carl Friedrich Cramer reporting from the French capital of rank, as well as the French quarterly literary journal Le Conservateur . None of the three projects was a great success. De Ster fell victim to censorship in August 1806 after the establishment of the Kingdom of Holland , the individualities had to be discontinued after Cramer's death in 1807 and the Conservateur only appeared for a year and a half from the beginning of 1807 to 1808.

Further publishing activities included the publication of literary works such as Cramer's translations of the Scottish woman Joanna Baillie , the Englishman John Pinkerton and the French Louis-Sébastien Mercier or the poems of the Dane Jens Immanuel Baggesen , scientific works such as the Historia rei herbariae and the Institutiones medicae von dem German doctor and botanist Kurt Sprengel or the Entozoorum sive vermium intestinalium historia naturalis by Karl Asmund Rudolphi . In addition, in 1807 he published the Itinéraire de l'Allemagne , written by Heinrich August Raabe , and thus expanded the publishing program to include travel literature. With the historical-military manual for the history of war from 1792 to 1808 by Baron Albrecht David Gabriel von Groß , he established the publishing tradition of militaria in 1808.

Purchase of the Löbelschen conversation lexicon

He took what was probably the most momentous step in his publishing career in the autumn of 1808 when he visited the Leipzig booksellers' fair: for the sum of 1,800 Reichstalers, which was modest at the time, he acquired the rights to the 1796 by Renatus Gotthelf Löbel under the title Conversationslexikon with excellent consideration The work started at the present time and initially published by Friedrich August Leupold in Leipzig, which he continuously expanded until his death in 1823 and which forms the basis for the Brockhaus Encyclopedia .

The founder of the work, about whose circumstances little is known today, described himself in his preface to the Conversations Lexicon as the successor to Johann Huebner , under whose name the Real State and Newspaper Lexicon , first published in 1704 , was known. Löbel's aim was to create a “dictionary appropriate to the current scope of the conversation”, which was to do justice to the “general pursuit of intellectual education, at least according to the appearance of it”, as he stated in his preface to the first volume. The first four volumes appeared between 1796 and 1800, but after Löbel's early death in 1799 everything initially looked as if it would remain unfinished. Then in 1806 a fifth volume was published by Johann Karl Werther in Leipzig and in 1808 parts of the sixth volume by Johann Friedrich Herzog in Leipzig. On October 25, 1808, Brockhaus finally bought the lexicon from the Leipzig book printer and newspaper publisher Friedrich Richter, who had probably printed the work on Herzog's behalf and who had taken it in payment when he went bankrupt.

Brockhaus was by no means the inventor of the "conversation lexicon", his achievement was rather to have recognized the opportunities of the unfinished Löbel dictionary and, through his work on it, to have laid the foundation for it to later develop into the "standard work of the German educated bourgeoisie" .

Altenburg

Return to Germany

Shortly after giving birth to her seventh child on November 24th, Sophie Brockhaus died on December 8th, 1809 of complications from a cold. This stroke of fate was joined by the resumption of the process with his former business partner Hiltrop at the beginning of 1810, which gave Brockhaus a hard time. The real trigger for his decision to return to Germany, however, is more likely to have been the worsening economic situation in Europe. The incorporation of the Kingdom of Holland into the French Empire - if only to close the last gaps in the Napoleonic continental blockade - was finally decided by the end of 1809 at the latest. The political changes were accompanied by a tightening of trade regulations, which forced Brockhaus to first ask in Paris for an import permit for each of his books printed in Germany. But this was not the only decisive factor, because from November 1809 the company was on the verge of bankruptcy due to a lack of capital. Brockhaus himself described the company's situation in retrospect in a letter to the banker Friedrich Christian Richter on April 21, 1811 as follows:

“My action had for the most part stalled and been interrupted since November; on the other hand the expense had gone; heavy taxes had to be paid, oppressive billeting had taken place; mine and the action credit were destroyed as a result of all disturbances; several creditors there, too, had sucked out all available forces through their pressure. "

In this situation Brockhaus left Amsterdam in May 1810 and - after a short stay in Leipzig - moved to Altenburg in Thuringia in September 1810 . He had previously placed his children in Dortmund.

The relationship with the councilor walks

During his four-month stay in Leipzig, Brockhaus and Johanna Karoline Wilhelmine Fahrt, the widow of the Leipzig court councilor, who died in 1805, and editor of the newspaper for the elegant world Karl Walk , sister-in-law of the poet Jean Paul and editor of the Urania annual calendar published by Brockhaus, had a close relationship developed. Since the beginning of August at the latest, Brockhaus has apparently had concrete marriage plans. After his arrival in Altenburg the following month, the plan matured to sell his Amsterdam company to his future bride in order to be able to pay his debts in the Netherlands. While he had succeeded in obtaining a deferral of payment with some of his creditors, the rest waived the rest of their claims only in return for a partial payment in cash. So Brockhaus was finally forced to sell his assortment business in a bogus store in order to continue it ten days later under the name "Typographisch-literary institute in Amsterdam and Leipzig" after the contract was canceled.

But his engagement was short-lived, because at the end of 1810 Wilhelminewalk fell seriously ill. After a febrile illness that was initially considered harmless, she fell into a state of mental confusion, which manifested itself in repeated attacks. When she confessed all her previous relationships to Brockhaus, believing that her death was approaching, he broke off the engagement. In a letter dated November 21, 1810 to Friedrich Bornträger, his employee and confidante at the time, he wrote: “This information makes it impossible for me to ever give her my hand. Oh God, from what heaven I fell. ”And further:“ I can perhaps give you this information - and only you - if, as I must wish, Minna should die! ”By the end of December 1810, the state of health of the Court councilor improved so much that Brockhaus wrote to Bornträger on the 29th: "She is no longer sick, but her whole being is broken". At the beginning of 1811 Brockhaus finally brought her back to her parents' house in Berlin . The correspondence exchanged between Wilhelmine Bewegungs and Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus after this time has not survived. Soon after separating from the court councilor, Brockhaus married Jeanette von Zschock in 1812 , with whom he had four more children. Due to tensions between Jeanette and Brockhaus' children from their first marriage, the relationship was difficult from the start and the marriage was divorced in 1821.

Publishing activity in Altenburg

After separating from Hofratin Walk, Brockhaus himself took over the publication of Urania , which during his time in Altenburg was one of the three main focuses of his publishing program and which shone simply because of its high-quality printing and careful illustration with copperplate engravings by well-known artists. It was one of the “pocket books for women” that was extremely popular at the time, consisting of a collection of contemporary prose pieces and poems and for Brockhaus authors such as Jean Paul , Theodor Körner , Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué , Gustav Schwab , Willibald Alexis , Ludwig Tieck and Eichendorff could win. The attempt made in 1812 to inspire Goethe for the project failed, however. Brockhaus himself appeared as a writer under the pseudonym "Guntram" in the year 1822 with the story The Rival of Herselves , but was not very successful. The Urania was discontinued in the course of the March Revolution of 1848 and thus only twenty-five years after his death.

In addition to the publication of contemporary German literature, Brockhaus was heavily involved in the political field. Between 1813 and 1816 he published the Deutsche Blätter , the official news organ of the Allies in the Wars of Liberation . In his own contributions he acted both as a reporter - for example from the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig in October 1813 - and as a critical commentator on the political circumstances of the time. With his comments, however, he came increasingly into the focus of censorship and finally gave up the company again in 1816 due to declining sales. But other publications from the Altenburg years also took up the turbulent political events of the time. Between 1812 and 1817 a number of war -history brochures , often directed against Napoleon , were published, whereby well-known authors such as Carl von Clausewitz or Karl von Müffling were not infrequently hidden behind the anonymously published statements . An anonymous work by the Austrian Josef von Hormayrs on the Tyrolean folk hero Andreas Hofer , which was first published in Altenburg in 1811 , also caused a stir .

From a financial point of view, the publication of the two-volume Handbook of German Literature from the middle of the eighteenth century to the present day by Johann Samuel Ed . The initiative to write this work went back to Brockhaus himself; With it, created the German scientific bibliography. For the publishing house, the high-selling manual was the second economic pillar of the Altenburg period alongside the conversation lexicon .

Brockhaus began the second edition of the Conversations Lexicon in 1812. By then, the lexicon had already had an eventful history. Renatus Gotthelf Löbel founded the work and together with the lawyer Christian Wilhelm Franke founded a publishing house in Leipzig in February 1796 to publish it . After Löbel's early death and Brockhaus' takeover of the lexicon, Franke committed himself to the completion of the sixth volume, which was only partially published. Brockhaus published the complete works in Amsterdam in 1809 and had two volumes with supplements to follow in the following years, as the lexicon had numerous gaps due to its long period of creation. Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus took charge of editing the second edition of the lexicon, which began in Altenburg in 1811, and has been supported by a growing number of selected employees since the beginning of 1812. The first revision of the lexicon was completed in 1818 and by the end of the same year all ten volumes of this second edition had appeared (the tenth and last volume appeared at the end of 1818 with the year 1819). At the same time as this second edition, Brockhaus had also prepared the third and fourth, so that at the time of the official move to Leipzig, parts of these editions were already available with new and revised texts.

Leipzig

"FA Brockhaus" Leipzig

Brockhaus had been in Leipzig permanently since the Easter fair in 1817 . For some time he had toyed with the idea of setting up his own printing company for the production of his conversation lexicon in addition to his publishing house, which had already been renamed "FA Brockhaus" in 1814 , and for this purpose he had sent his eldest son Friedrich to study printing in Braunschweig. In addition to the fact that there was already a printing company run by his friend Johann Friedrich Pierer in Altenburg , there was, on the one hand, the narrow circle of his acquaintances there, but above all the fact that Leipzig was the center of the book trade at the time, which made Brockhaus move there moved. On January 21, 1818 he was granted citizenship in Leipzig and in April he and his family moved into an apartment on the Leipziger Markt. Just five days later he opened his printing house and from 1819 all of his books appeared exclusively under the new publishing location Leipzig. The Conversations-Lexikon continued to be the focus of his publishing activity, but he also devoted himself to various political-literary magazine projects.

Journalism critical of time and literature

The Isis or Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken , published by the natural scientist Lorenz Oken , was a direct continuation of the Deutsche Blätter and, in contrast to these, was not intended to deal with any political issues, but was limited to treatises from the fields of natural sciences, art, history and literature . However, since Oken did not stick to his own announcement and also took up political contributions, Isis repeatedly came on the verge of being banned by the censors. In 1819 Oken himself faced the decision to either stop publishing Isis or resign from his professorship. He finally decided on the latter and continued working on the magazine unchanged. It was not until 1824, a year after Brockhaus' death, that he restricted the articles to be included solely to scientific topics.

Just like the Isis , the series was also contemporaries. Biographies and Characteristics was established as early as 1816. Since 1818 the series has been published by Brockhaus himself and formed the main part of his journalistic publishing activities in Leipzig. The work presented the biographies of people from contemporary history who were still living or deceased at the time, thus adopting a concept that had already proven itself in England. The articles published in Die Zeitgenossen were written, among others, by authors such as Karl August Varnhagen von Ense , Karl Friedrich Reinhard and August Wilhelm von Schlegel , although the authors of the biographies of people who were still alive were not identified. After Brockhaus' death, the contemporaries continued until 1841 and thus appeared for a total of 25 years without interruption.

In addition to the Leipziger Kunstblatt , which was discontinued at an early stage for educated art lovers , the two literary-critical journals Hermes or Critical Yearbook of Literature and Literary Weekly expanded the publishing program. The emergence of Hermes goes back to the lifting of the continental blockade after the fall of Napoleon, which not only made English manufactured goods and non-European goods from the English colonies, but also English literature again available in large quantities on the continent. The Hermes was originally designed by Brockhaus as a journal "which was supposed to make up for what was neglected in the knowledge of English affairs within seven years". In the years between its first publication in 1819 and its discontinuation in 1831, the magazine developed into a review body of new literary publications, and its staff included a number of renowned German professors - including Wilhelm Grimm , Johann Friedrich Herbart and Friedrich von Raumer . In contrast to the Hermes , the literary weekly was designed for entertainment and thus addressed a wider audience. The magazine was originally founded in 1818 by August von Kotzebue and was bought by Brockhaus after his murder in 1819 and published under his own direction a year later. The paper was so successful with its conception that it remained in the publisher's range until 1898 - with changing titles.

The rest of the publishing program

In the field of monographs, the publisher's focus was on works of history, politics and - not infrequently as a by-product of the conversational lexicon or series like the contemporaries - biographies. The work From the memoirs of the Venetian Jacob Casanova de Seingalt, published in 1821 , or his life, as he wrote it down at Dux in Bohemia in the adaptation of Wilhelm von Schütz , provoked a violent reaction, which was severely attacked after its publication. In the field of history, Raumer's lectures on ancient history (1821) and his six-volume history of the Hohen Staufen and its time (1823–1825) should be emphasized. In the field of philosophy Brockhaus published in 1818 with Die Welt als Wille undführung, the main work of the then almost unknown Arthur Schopenhauer .

Fight against Macklot's emphasis

After the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806, copyright law was handled differently in the various German territories. Karl Erhard, owner of the Macklot printing house in Stuttgart , used this fact to reprint Brockhaus'schen Conversations-Lexikon . In Wuerttemberg reprints were allowed for printed works not appearing in the state and so the Macklot publishing house announced in 1816 a cheaper edition of the lexicon for southern Germany, which “with Königl. Württemberg's most gracious approval ”was printed and“ should also make it easier for unprofessional readers to acquire the work ”. Brockhaus traveled to Stuttgart and in turn obtained a royal privilege for the fourth edition of his lexicon, which was held between 1817 and 1819, but he lost the trial against Macklot in all three instances.

In addition to the dispute in court, Brockhaus fought vehemently to protect his interests on other levels as well. At the beginning of July 1818 he published a leaflet to the public in which he denounced the reproduction by Macklot as theft and not only placed this pamphlet in all of his publisher's journals and all volumes of the Conversations-Lexikon , but also mailed it to all members of the Bundestag and the press. While his advance at the Bundestag later fizzled out, the large-scale campaign against Macklot ultimately led to success. Public opinion backed Brockhaus and sales of his lexicon rose considerably. At the same time, the second edition of Macklot's reprint had to be largely blamed, whereupon Erhard withdrew from the book trade, disappointed.

Last years

In April 1820 the fifth edition of the Conversations Lexicon was completed. The work sold so well that Brockhaus finished the second reprint in September of the same year. Since he was very busy with the journals he directed and some buyers of the encyclopedia had already complained that their edition was quickly out of date, he had announced in one of his business circulars from March 1819 that for the time being no further revision in the form of a sixth edition to follow. In the summer of 1821 a third, largely unchanged reprint of the fifth edition appeared, the topicality of which was to be ensured by a supplement volume planned for the next few years. This extension was also delivered from 1822 under the title Conversations-Lexikon über die neue Zeit und Literatur , but after the third reprint of the fifth edition of the Conversations-Lexikon was already out of print in the summer of 1822, Brockhaus finally decided to revise it. This sixth edition was produced between the summer of 1822 and the summer of 1823 and was thus also the last edition that was created under the direction of the publisher's founder himself, but Brockhaus did not live to see it appear in 1824.

Two years before his death, Brockhaus had implemented a long-cherished plan and in May 1821 bought a large piece of land on the eastern edge of Leipzig , which served him both as a new residence and as a location for his expanding company. Later, other booksellers and related branches of business settled in the vicinity, so that after Brockhaus' death a new bookseller's quarter was created.

His sons had supported him in the company since Easter 1819. After spending a year abroad in Paris and London, Friedrich took over the management of the printing house in October 1820 and was also registered as the owner of the new property after the ongoing trial against his former business partner Hiltrop entered its final phase in August 1819 been. His second son Heinrich joined the company at the age of fifteen and, like his older brother, was supposed to go abroad for a year when Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus became seriously ill at the end of 1822 and the trip was postponed indefinitely. Hermann , the third son, did an apprenticeship in 1821 in his father's publishing business in Leipzig, after which he continued his high school studies.

Brockhaus had already felt sick and attacked in the autumn of 1822. On the advice of his doctor, he wanted to go on a recreational trip to Paris, but that didn't happen. From the last week of November onwards, his condition deteriorated rapidly, and on December 3rd he made his will. After his death was erroneously reported in the newspapers, he recovered. The false report had provoked different reactions in the meantime. While most of the voices expressed deep regret about the supposed loss, Brockhaus also had to find out about occasional expressions of joy. At the news of his recovery, many of his friends urged him to limit his previous activities, which Brockhaus firmly resolved to do. But the prediction of the poet Helmina von Chézy , who had written to him, "Here in Berlin you have been generally and definitely declared dead, which means a long life", should not come true. In May 1823 Brockhaus visited the Leipzig Easter Fair for the last time and by the end of July his health deteriorated again. A few weeks later, on August 20, 1823, he died at the age of 51. As an anticipation of the future, his son Heinrich wrote in his diary shortly after his father's death: "What he has created should live on!"

Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus in the judgment of his biographers

Even during his lifetime, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus' assessments diverged widely. This controversy in assessing himself and his performance continued unabated after his death. His close friend and long-time employee at the Conversations-Lexikon , the Dresden professor Friedrich Christian August Hasse, described him with the words: “As a good and good-natured person, but often misunderstood and bitterly hostile; as a businessman with an ingenious and free-spirited way, nevertheless misjudged in misfortune and much envied after cheap successes achieved late, Brockhaus shared the fate of most men of talent, for whom mediocrity can never forgive small mistakes. "

His grandson Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus made a far more balanced judgment: “Brockhaus' sanguine-choleric temperament, the lively aversion that he felt for every injustice or injustice [...] finally also the self-confidence that he has developed ever more strongly since he was in hard struggles and, essentially through his own strength, had gained recognition, names and successes: these various moments worked together to allow him to easily get into disputes, as with colleagues and authorities, and with writers ”. Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus was an autodidact who wrote the three-volume biography about his grandfather in his spare time and also evaluated hundreds of business and private letters. His work represents the basis for any further investigation on Brockhaus to this day, because many of the documents that were printed in the text in his biography, which appeared between 1872 and 1881, are no longer available in the original due to war losses. The festschrift from his hand, published in October 1905 for the centenary of the publisher, only contained a revised concentrate of these three volumes and did not unearth any new knowledge.

Among the more recent representations, Gertrud Milkereit's life summary from 1983 should be emphasized. Milkereit introduces Brockhaus as a liberal democrat whose strengths at the end of his life were drained by his political commitment. The portrayal of his person is balanced and does not hide Brockhaus' choleric inclination, nor does it downplay his pronounced willingness to process. Misjudgments in publishing are named as such, but without losing sight of Brockhaus' overall performance for the German publishing industry. A selection of the works published by Brockhaus between 1805 and 1823 rounds off the article. In contrast, the thirteen-page biographical sketch by Anja zum Hingst sheds little light on Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. The repeated entrepreneurial failure is presented as the sole consequence of unfavorable circumstances, which Brockhaus countered again and again with a “feel for the zeitgeist”, “commercial experience”, “strict management” and “genius”. With the benevolent perspective that shines through solely in the selection of the event-historical facts presented, the life sketch falls behind earlier depictions.

literature

swell

- Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus on the reprint of the Conversations Lexicon by Macklot (1818) , as a digitized version and electronic full text in the Wikisource project .

- Heinrich Brockhaus: Complete directory of the works published by FA Brockhaus in Leipzig from its foundation by Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus in 1805 up to his centenary birthday in 1872 , Volume 1, Leipzig 1872.

- Heinrich Lüdeke von Möllendorff: From Tieck's time of novels. Correspondence between Ludwig Tieck and FA Brockhaus , Leipzig 1928.

- Ludger Lütkehaus (Ed.): The book as will and concept. Arthur Schopenhauer's correspondence with Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-40956-3 .

Representations

- Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus: From the foundation to the centenary 1805–1905 , facsimile of the Leipzig 1905 edition, with an introduction by Thomas Keiderling, Mannheim 2005, ISBN 3-7653-0184-1 .

- Ders .: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. His life and work described based on letters and other records , 3 volumes, Leipzig 1872–1881.

- Friedrich Christian August Hasse: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Outline of life , in: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Commemorative sheets for the centenary of death on August 20, 1923, Leipzig 1923.

- John Hennig: An unpublished letter from KA Varnhagen von Ense to FA Brockhaus. in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 47, 3 (1965), pp. 355-360, ISSN 0003-9233 .

- Anja zum Hingst: The history of the Großer Brockhaus: from Conversationslexikon zur Enzyklopädie , Wiesbaden 1995, pp. 78–91, ISBN 3-447-03740-7

- Arthur Hübscher: One hundred and fifty years FA Brockhaus 1805–1955 , Wiesbaden 1955.

- Annemarie Meiner: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 623 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Gertrud Milkereit: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (1772–1823) , in: Rheinisch-Westfälische Wirtschaftsbiographien, Volume 11, Münster 1983, pp. 5–41, ISBN 3-402-05586-4

- Otto Mühlbrecht: Brockhaus . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1876, pp. 337-340.

- Jürgen Weiß: BG Teubner on the 225th birthday. Adam Ries - Völkerschlacht - FA Brockhaus - Augustusplatz - Leipziger Zeitung - Börsenblatt , Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-937219-35-6 .

See also

- The database of the bookselling business circulars of the German Museum of Books and Writing with data from business circulars relating to the book trade from the middle of the 18th century

- The online finding aid for the archive material of the FA Brockhaus publishing house in the Saxon State Archives, Leipzig State Archives

Web links

- europeana : Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus

- Literature by and about Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Leipziger Kunstblatt for educated art lovers, especially for theater and music , Volume 1, Leipzig 1817/18 (digitization of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich).

- Leipzig F. A. Brockhaus high school

Remarks

- ↑ Heinrich Brockhaus: Complete list of the works published by FA Brockhaus in Leipzig from its foundation by Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus in 1805 until his centenary birthday in 1872 , Leipzig 1872, Volume 1, p. 34.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 1, pp. 45f.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 1, p. 50.

- ^ Gertrud Milkereit: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus, 1772–1812. in: Rheinisch-Westfälische Wirtschaftsbiographien , Volume 11, Münster 1983, pp. 5–41, ISBN 3-402-05586-4 . P. 10.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 1, p. 243.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 1, p. 201.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 1, p. 207.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 2, pp. 229f.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 3, p. 474.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 3, p. 498.

- ^ Friedrich Christian August Hasse: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Outline of life , in: Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus, memorial sheets for the centenary of death on August 20, 1923, Leipzig 1923, p. 7 f.

- ^ Heinrich Eduard Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus , Volume 3, p. 104.

- ↑ Kristina Barth, Hannelore Effelsberg: Booksellers Business Circulars - Introduction ( Memento of December 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) of March 9, 2004, in the version of December 16, 2013 permanently saved in the Internet Archive

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Brockhaus, Friedrich Arnold |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German publisher, founder of the publishing house "FA Brockhaus" |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 4, 1772 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dortmund |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 20, 1823 |

| Place of death | Leipzig |