The world as will and idea

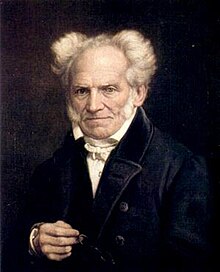

The world as will and idea is the main work of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), published in 1819.

The first edition (1819) of the work appeared in the Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus in Leipzig.

Work structure

The work has consisted of two volumes since the second edition in 1844. The first volume contains the text of the first edition, which has only been given a few minor additions, while the appendix - the critique of Kantian philosophy - was largely edited by the author. Volume I is divided into four books in which the world is viewed alternately as an idea and the world as a will. The second, larger volume, serves as a supplement to the first.

In the preface, Schopenhauer justified the procedure of putting the additions in the separate volume by stating that there were 24 years between the appearance of the first and second edition. In contrast to a revision, the development of Schopenhauer's thinking should be able to be followed.

The professional and broad-based reception of Schopenhauer's writings came very late, in the last years of Schopenhauer's life. In the preface to the third edition (supplemented by a further 136 pages) Schopenhauer appears relieved, but also exhausted. He refers to further additions in the second volume of Parerga and Paralipomena , which he made appear seven years after the publication of the second edition of Die Welt as Will and Idea : “... [it] would have found its right place in these volumes: but at that time I had to put it where I could, since it was very doubtful whether I would see this third edition ”. The third edition appeared in 1859 - a year before his death.

content

Schopenhauer's main work can be divided into four areas, each of which is the subject of the individual books in the first volume of the world as will and conception: epistemology , metaphysics , aesthetics and ethics .

The main subject is Schopenhauer's assumption that on the one hand the world is will, on the other hand it is only given as our imagination, as the title makes clear. Under notion Schopenhauer understands the mental functions that are responsible for the modality of recognizing a recognized animal. Under will understand Schopenhauer, inspired by Eastern philosophy, a cosmic principle of existence, which is responsible for the individual's existence in the world and, among others, can be described "a blind aimless urge to life" as. For Schopenhauer, people, animals, plants, as well as stones or all forms of matter, are part of this principle. Schopenhauer sees the thing-in-itself in the principle of the will . According to Schopenhauer, there is an individuality, a diversity only in the world of objects. The will forms the unity that is present in the same degree in man as in stone.

Schopenhauer is of the opinion that the individual imagination prevents us from recognizing the world as it is, i.e. the will, in everything and not just in ourselves. Schopenhauer sees in a conception of the world that is perceived purely as an idea that is subjectively measured by the individual will, among other things, an explanation for egoism. In the denial of our individual will, there is a way out of the world as a pure idea, whereby we can recognize the same will and the same suffering in everything. Schopenhauer's metaphysics is therefore closely linked to his ethics. According to Schopenhauer, art offers a possibility of temporary negation of will.

Epistemology

As an introduction and propaedeutic , Schopenhauer cites his dissertation on the fourfold root of the proposition of sufficient reason in the preface . The principle of sufficient reason is a logical-metaphysical principle established by Leibniz , which states that everything that is has a reason why it is ( Nihil sine ratione ). Schopenhauer, however, already finds the sentence implicit in Plato and Aristotle . The basis of his treatise is the criticism of a confusion of cause and ground of knowledge, as he observes within the definitions of the principle of sufficient ground, as well as in the application of the same. For Schopenhauer there are essentially two different meanings of the principle of reason in the history of philosophy: the demand for a ground of knowledge, as the justification of a judgment, and that of a cause for the occurrence of a real process.

Following a quote from Aristotle, Schopenhauer comes to the conclusion that the definition of a thing and the proof of its existence are fundamentally different, even if both satisfy the requirement made in the principle of sufficient reason. In the course of the dissertation, Schopenhauer finally found four different meanings of the principle of sufficient reason, its 'four roots'. Together they form Schopenhauer's theory of the capacity for knowledge and form the basis of his entire philosophy: the system of voluntaristic metaphysics developed in the main work .

According to Schopenhauer, the pure subject of knowledge is the starting point for all knowledge. Everything that lies outside - including one's own body - represents an object and is therefore subject to the principle of reason as an idea - however, nothing imaginary is meant by idea. Schopenhauer wants the term idea to be understood literally, in the sense of: something that is placed in front of you ( object ). Building on the basic a priori of space , time and causality , the idea is a product of four roots: The mental functions: the mind, reason, pure sensuality and self-confidence. Together these result in the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason, since all cognitive functions follow the principle of reason.

Everything that we perceive with our senses can never be grasped by the subject in an unsystematized form, but is always brought into separate structures, to a perception for a knowing subject. We are separated physically and by imagination from the in-themselves of things. The world as an idea, the objects for the subject, is a conception of objects that in this way do not exist in themselves .

Schopenhauer is of the opinion that the idea is subject to the will, and that the individuality of the ideas and individuality in themselves are products of the will. Each individual accordingly has his own idea of reality, against which the outside world is measured, which is part of the circumstance of a subject-object relationship. The world is given to all cognizing living beings only indirectly through the cognitive functions used. The thing in itself is purely for Schopenhauer the will that is behind everything that constitutes our imagination and come under his control. The will is the principle that lies behind all objects and enables and influences our conception of objects.

The following section combines the content of the dissertation with the additions to the first and second volumes of the main work, "The world as will and imagination" .

The four roots of the principle of sufficient reason

Schopenhauer essentially divides imagination into abstract, which only concerns the concepts, and into intuitive, "... [which deals] with the whole visible world or the entire experience, together with the condition of the possibility of the same." The abstract imagination forms reason , the mind is the intuitive concept.

The two other classes form pure sensuality, the principle of the ground of being, and self-consciousness, the principle of the ground of action. The latter two differ in that they can be used to ask why. Together they form the four roots of the principle of sufficient reason, the objects for the subject. The principle of reason says that everything that is has a reason why it is . In terms the principle of reason is purely abstract; it becomes intuitive through the perception of matter. Through the conditions of space and time it shows itself in the pure intuition, the a priori condition of space and time, whereby it can only be felt through intuition. Ultimately, the motive can be used to grasp the motive through self-confidence.

- To the order

This article follows the order in which the individual classes were explained, as made by Schopenhauer, for practical reasons, in the dissertation on the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason . In a systematic order, the order is as follows: Beginning with the ground of being in the application to time, since this is the essential scheme of all other forms of the principle of sufficient ground, this is followed by the application of the ground of being to space. This is followed by the law of causality, the principle of the ground of becoming. This is followed by the principle of the ground of action, the motive, and finally the principle of the ground of knowing, since the previous one is based on immediate representations, this however on representation from representation.

Intuitive idea

The principle of the reason for becoming

The principle of the ground of becoming (causality) determines that all changes in objects of empirical reality must always have a cause. In contrast to the ground of knowledge, the intuition which is given by the understanding concerns only the present moment, which is received by the senses. Schopenhauer sees in the law of causality, the necessity of cause and effect, the ability to make hypothetical judgments. The content of thinking forms only an abstraction of perception, so it must be traceable back to our perception or reconstructed, or have a reason for not becoming empty thinking. Schopenhauer emphasizes several times that all concepts can be controlled by perception and, with regard to perception, as in general, explicitly opposes a purely rational, abstract philosophy.

In contrast to Kant, Schopenhauer sees causality or understanding as the condition of all intuition and not as a power of thinking; the application of the law of causality as intuitive, not abstract. The subjective correlate of this class of ideas is the mind.

understanding

The understanding represents the corrective cerebral function, whose activity, according to Schopenhauer, is purely the application of the law of causality, which corrects the sensory perception , the sensory stimulus that acts on the body (object) , to an intuition for the subject. Using the example of vision: an image hits the retina upside down . The mind processes the information of the two-dimensional images of the two eyes back into an upright one. The mind produces a three-dimensional image from the information from the senses , from the data from the senses, such as surfaces and edges. The processed data becomes an illustration : the primary knowledge. Finally, concepts can be formed from the objective world produced by the intellect, intuition , by means of reason, secondary knowledge. The knowing consciousness is formed from understanding and reason.

The body plays a special role in the media: although sensation is subjective, the body remains an object for the subject, albeit immediately , since the external sense is indispensable for the internal sense in order to enable an intuition (see section Understanding as a subjective correlate of matter ). Schopenhauer distinguishes between the inner sense , the immediate subject, and the outer sense , which is the body: both are basically considered "subjective" - although we understand the body as an object - and immediate, since we do not directly, but only indirectly, between sensation be able to compare different bodies. The same applies to the knowing subject, which cannot be compared with another knowing subject - it would thereby be an object. Everything mediocre is only multiplicity, the world of experience, the visualization of objects in space and time that lie outside of ourselves and require an intermediate function, such as that of the mind. The knowing subject , viewed alone, forms a unit and has only a medial function, cannot imagine the manner of its cognition, respectively cannot cognize the cognition, the subject in turn can only become the object of the imagination of the subject (cf. on the principle of the ground of action ).

According to Schopenhauer, the way in which objects are imagined, which the knowing subject grasps, is subject to individuality and its selection, which are the product of the will, similar to the definition of an unconscious drive that is common today.

Subject and object

The core of his conclusion is the definition of consciousness, which breaks down into subject and object. Since the understanding first processes the sensation, the subject, as a cognitive function, can never be thought without an object, or an object can never be thought without a subject, which first offers the possibility of cognition. Schopenhauer wants to show that the empirical perception is an intellectual one, only through an object, from sensation through the mind to perception, the subject can recognize something : that a consciousness is always a consciousness of something . If an object is given, there must be a subject who knows ( George Berkeley ). And vice versa: if there is a subject that knows, there must be an object that is known. The latter is Schopenhauer's extension of Berkeley's philosophy.

Schopenhauer wants to emphasize that the subject perceives nothing other than the idea of objects, this forms the subject's only function, but also restriction, dependency and distance to the object, which is always perceived indirectly or purely subjectively by the subject. If there were no subject, there would be no object, and thus also no view of a world, and vice versa, since the object is just as dependent on the subject. Schopenhauer tries not only to emphasize the subjective, that which is always relative to the perception of man, but also the dependence of the world on the subject: if the subject is posited, so is the object and vice versa. From this it follows that it does not matter whether one determines objects in any way or whether one says that one knows them in just the same way: subject and object are inseparable in the process of knowing. This thesis has an impact above all on the question of a thing-in-itself , which, if an object is always there for a subject, and vice versa, becomes nonsensical, only conceptually not talking about a thing- in-itself, there is no perception of Objects outside of our property. Schopenhauer concludes from this that the will, which does not mean an explicit motive, but rather a kind of drive than that which is solely given to us directly, can be the only access to the in-itself of things. (See section on the principle of the reason for action .)

intellect

From this idealistic conception of the relationship between subject and object, taken from Berkeley and expanded by physiology, two considerations of the intellect emerge:

- The world as an idea is only given as such by the presenting subject. The first consideration is the investigation of the a priori and the emergence of empirical reality, as a result of the capacity for knowledge, and follows the transcendental idealistic view of Kant - which was greatly restricted and modified by Schopenhauer:

"I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrinal concept, according to which we see them as a whole as a mere idea and not as a thing in itself [.]"

"If I take away the thinking subject, the whole world of the body must fall away, as this is nothing but the appearance in the sensuality of our subject and a kind of representation of the same."

- The second consideration, based on the object, is the materialistic one, forms the compensatory corrective of the purely transcendental idealistic consideration, integrates knowledge of the formerly contemporary physiology and includes the objections to idealism in the overall consideration of the intellect: just as matter is the representation of the subject the knowing subject is also a product of matter, since the intellect is a product of the brain. Schopenhauer criticizes the materialistic view as a self-forgetting subject , but only in the sense of a one-sided view of the world as a purely materialistic one, which thinks to find the thing-in-itself in matter . In summary, Schopenhauer writes:

“Of course, in my explanation, the existence of the body presupposes the world as an idea; in so far as it too is only in it as a body or real object: and on the other hand, the idea itself just as much presupposes the body; since it only arises through the function of an organ of the same. "

Schopenhauer eludes a clear stance, rather tries to clarify the juxtaposition of realism and materialism on the one hand, idealism and dogmatism on the other, and culminates his observations in a criticism of the debate about the reality of the world.

Mind as a subjective correlate of matter

The union of the inner (knowing subject) and outer sense (body: the five senses), through the understanding, forms the conception of matter. Schopenhauer calls the subject something immediate : a unity that confronts the multitude of objects. The inner sense is incumbent on the limitation of time. Since for the inner sense the outer senses are again only objects (body) of the same, the body again only perceives the perception of the body, thus only grasping the immediate presence of the idea in its consciousness, the form of the inner sense remains subject to time, it can only gradually perceive. The succession, the one after the other , which only becomes possible through time, is conditioned by the juxtaposition in space. Representations are not only recognized in the process of unifying space and time, to form an overall representation of empirical reality, but, as representations purely of the inner sense (subject), are only recognized in time: On the point of indifference between the two diverging directions of time: in the present.

The inner sense takes the outer senses to help, whereby the outer can arise in the mind: space. Only when the understanding, the brain, becomes active, the only form of which is the application of the a priori law of causality, since experience (perception) is not possible without understanding and its form of activity , the subjective sensation can be processed into an objective perception. By linking the directly subjective (time), which includes the sequence of changes, the succession in space, hence cause and effect, with the perception of the external senses, the perception of which is understood by the mind as an effect, the empirical view arises, objects become in the Indirect space , experience arises .

Space, time and causality

In mere space the world would be rigid and immobile, which would, however, cancel out ideas, and therefore matter - since no successions are possible, nothing changes. In mere time there would be no persistence, hence no duration.

In the coexistence of many states of matter, in the juxtaposition in space and succession in time, there is a reality. It is matter on which space and time can exist; it forms the union of both and is the basis of all imagination. Space and time can only be experienced through matter. Likewise, as imaginative beings, we are only a form of matter (our body, its senses), we can only experience something through matter when we ourselves are a form or a state of matter. The cerebral function of the mind enables us to do this; it forms the subjective correlate of matter. For the reason that we ourselves are matter, can only experience something through matter, matter only exists by means of the law of causality, which connects space and time in matter by changing the form within a time in space Schopenhauer, the being of things purely in action: matter and causality are synonymous.

The form of the appearance of any object is in space and in time: the object has duration, a place and movement; through the here there is the there ; the after exists through the before , the present between the two. According to Schopenhauer, time and space can only be viewed a priori in their infinite divisibility and infinite extension; they are alien to empirical perception. Space and time can only be experienced through and on matter. The link between space and time is causality.

Schopenhauer defines causality as follows:

“When a new state of one or more real objects occurs; so it must have been preceded by another, followed by the new one regularly, that is, whenever the former is there. Such a following is called a success and the first state is the cause, the second is the effect. "

The law of causality relates exclusively to change . Every effect is a change when it occurs and indicates another change that has preceded it , which, in relation to the present cause , but in relation to a third or necessary previous change is called effect: the chain of causality is necessarily beginningless or infinite.

Law of Inertia and Law of Persistence of Substance

As long as nothing changes, no cause is to be asked: The law of inertia says that every state, its rest as well as movement of any kind, must endure endless time, provided that there is no cause from which a change occurs.

Schopenhauer criticized the "cosmological proof" that the existence of a not- closes and stops at a first cause, "like a parricide," to which Schopenhauer the "talk" of a absolutum returns. According to Schopenhauer's definition, a first cause is as impossible to think as a beginning of time or a limit of space. According to Schopenhauer, there is no a priori reason to infer from the existence of existing things, ie states of matter, about their previous non-existence , nor to infer from this about their origin, i.e. about a change. The change and causality only refer to states of matter .

“The connection of the form with the matter or the essentia with the existentia gives the concrete, which is always something individual, that is the thing : and it is the forms, their connection with matter, ie their entry into this by means of a change , the Laws of causality. "

Schopenhauer criticizes an overly broad definition of the causal principle, in which one concludes that one object is the cause of another object: Objects not only contain form and quality, but also matter, but this neither arises nor disappears, except for their form. States are what is understood by form in the broader sense. The matter, however, persists.

“However, our knowledge of the persistence of substance, that is, of matter, must be based on an a priori insight; since it is above all doubt and therefore cannot be drawn from experience. I derive it from the fact that the principle of all becoming and passing away, the law of causality, of which we are a priori conscious, essentially only affects change, that is, the successive states of matter, that is, it is limited to form, matter leaves untouched, which therefore stands there in our consciousness as the basis of things, which is not subject to any becoming or decaying, therefore has always been and always remains. "

In Schopenhauer's view there is only one matter, and all different substances are different states or forms of the same: as such it is called substance. Schopenhauer differentiates between empirically given matter (substances) entered into a form, and general pure matter, which is only the object of thought, not that of perception, since we only perceive the form of matter through causality.

"Really, by pure matter we think of the mere activity in abstracto , quite apart from the nature of this activity, that is, pure causality itself: and as such it is not an object but a condition of experience [.]"

Only matter (substance) and the forces of nature (gravity, impenetrability, rigidity, electricity, etc.) remain unaffected by the chain of causality, since this also determines the condition of causality, everything else of causality.

"In general, the law of causality applies to all things in the world, but not to the world itself: for it is immanent in the world , not transcendent and canceled with it."

Matter functions as the carrier of change, that which such changes ; The force of nature, however, only gives the possibility that matter can change because the latter borrows the manner of change from the forces of nature, which are omnipresent and inexhaustible, always ready to express themselves as soon as the opportunity arises on the guide of causality.

"The norm which a natural force obeys with regard to its appearance on the chain of causes and effects, that is, the bond that connects it with this, is the natural law."

For Schopenhauer, matter forms the causality objectively understood by the mind. Your whole being consists in working.

According to this, the essence, '' essentia '', of matter consists in action in general , reality, existentia, but of things precisely in their materiality, which is thus again one with action in general; so it can be said of matter that existentia and essentia coincide with it. "

At this point, too, he indicated the two ways of looking at the intellect (see above ). For him it is certain that the world exists and is not only thought of in pure form, since our body is also made of matter, but we are still only within the limits of our imagination.

Schopenhauer sees the “cosmological proof” as one of many examples of the misuse of general terms that are lost in abstraction. Schopenhauer warns of the "susceptibility" and the "insidious" of the abstract , if the perception is not the source of knowledge or the concept, or the intuitive contradicts the abstract idea and the latter nevertheless claims absolute validity, which Schopenhauer in the ever sees its own intentions of the respective author justified: in the will to which the idea of an individual is subject. Schopenhauer holds on to the transcendental idealistic view that the world is an idea for a subject, but formulates his own criticism of reason based on his views - ultimately a criticism of language:

"It [philosophy] is not, as Kant defines it, a science in terms, but in terms."

The principle of the reason for knowing

The principle of the reason for knowing says that the connections between concepts and judgments always have a reason which can be asked: reason and consequence. The abstract imagination operates with terms that raise the vivid imagination to thought, break it down into its components and reduce it, but also lose their vividness. Schopenhauer therefore also calls concepts representation from representations.

The principle of the ground of being

The principle of the ground of being (space and time), including geometry with regard to space, and arithmetic with regard to time, is the sequence of its moments in time and the position of its parts, which are mutually defining in infinity, in space .

"Now the law according to which the parts of space and time determine each other with the intention of those relationships, I call the principle of the sufficient reason of being."

According to Schopenhauer, this occupies a special position, since space and time, which perception recognizes a priori , apply as a law or condition for all possible experience, and treats the a priori given perceptions of the forms of the inner (time) and outer sense (space ) and forms the formal part of the complete presentation.

"[...] pure points and lines [cannot be represented], but can only be viewed a priori [...], just as the infinite extension and infinite divisibility of space and time are solely objects of pure intuition and foreign to empirical". "

Only the causality represents the link between space and time: When (time) something happens presupposes what (space) happens. Conversely: the question of what happens presupposes knowledge of the sequence of things in time. Matter is causality that has become objective; only it forms the perceptibility of time and space.

Schopenhauer sees arithmetic as conditioned by the ground of being, in time. Time knows only one dimension: that every moment is conditioned by the previous one. All counting is based on the same principle in that arithmetic is a methodological abbreviation of counting. Example: You can only get to the number ten through all previous numbers, which also reveals that where the ten are also eight, seven, six, etc.

The geometry is based on the relationship between the position of the parts of the room.

Since there is no succession in space, since this is only given in combination with time to form the overall concept, there is an analogue of interaction everywhere .

"Therefore it does not matter which [line of surfaces, bodies, points] one wants to see first as determined and the others as determining, ie as ratio [reason] and the others as rationata [justified]."

Therefore it is valid at the bottom of being, as with the bottom of becoming, that the chainings never end.

The difference to the bottom of the recognition is, according to Schopenhauer that the necessary consequence of the conditioned can be seen from the condition from the knowledge of being ground, such as, the fact of the equality of the sides of a triangle and the equality of the angles, in conjunction are given whereas the existence of both facts is present through the ground of knowledge .

“Is [it] just a reason for knowledge? No, because the equality of the angles is not just proof of the equality of the sides, not just the basis of a judgment: from mere concepts it can never be seen that, because angles are equal, the sides must also be the same; for the concept of equality of angles does not include that of equality of sides. So there is no connection here between concepts and judgments, but between sides and angles. "

In Schopenhauer's view, the difference lies in the fact that concepts do not provide a knowledge of space and time, that being so differs from a judgment in that the latter does not control space and time. Terms are taken from perception. The world and its objects in the world, as well as judgments about it, are based on the conditions of space and time, are therefore a separate instance, different from the ground of knowledge, since the condition of space and time does not arise from the ground of knowledge.

"The equality of the angles is not the direct reason for recognizing the equality of the sides, but only indirectly , in that it is the basis of being like this , here of the equality of the sides: because the angles are the same, the sides must be the same."

The principle of the ground of becoming is also different from the ground of being, since it is not a question of changes and causes which only take place in the form of matter, the condition of which is space and time; matter is in it and not space and time through matter. In arithmetic, with respect to time, the difference is also given. Causality only dominates the events in time, not time itself. The essence of time, its one-dimensionality, cannot be determined purely on the basis of the basis of knowledge.

“[...] So why is the past irretrievable, the future inevitable? cannot be shown purely logically by means of mere concepts. "

According to Schopenhauer, the condition of space and time cannot be understood or clarified from mere concepts, but we recognize it very directly and intuitively, as a basic mode of knowledge, such as the difference between left and right, and it is only understandable by looking at it . The condition of reason and consequence or the why cannot be determined through the knowledge base alone . The question can only be answered through the ground of being and in perception.

For a better understanding, in dealing with the different classes, Schopenhauer emphasizes:

“It goes without saying that the insight into such a ground of being can become the ground of knowledge, just like the insight into the law of causality and its application to a certain case, is the ground of knowledge of the effect, but by no means the complete difference between the ground of Being, becoming and knowing is abolished. "

The subjective correlate of this class is pure sensuality.

The principle of the reason for action

The principle of the ground of action determines the motive of the will (motivation ground ) for which the knowing subject is the object (the object of inner sensuality). Because the subject regards itself as an object, it is divided into what is known (subject) and what is known (objectification of the subject). Since the knowing subject, the representing ego, the necessary correlate of all representations, is thereby a condition of the same, it cannot itself become a representation: the knowing consciousness (subject) within the representation as self-consciousness (principle of the ground of action) cannot know of knowing, since the presenting I (subject) is only a pure idea, again only an object for the subject, whereby the knowing subject can never become an idea or an object in itself, but only its objectification becomes an idea: the knowing subject knows the subject of will. Here the recognized object, which is the subject, appears for the first time as an objectified will, in that the subject recognizes itself - as an immediate object - as something willing and at this point shows the transition to the later main work. The ego is thus composed of the subject of willing and the subject of knowing. Schopenhauer points out that this class of imagination is not really a separate class. At the moment when the subject becomes an object, it is actually again a matter of the principle of the ground of becoming. Self-confidence forms the presentation of one's own life course: our own individual actions according to motives.

If knowing could actually be known, it would require the subject to separate from the knowing in order to be able to know the knowing. A split that Schopenhauer believes is impossible. The fact that we know powers of cognition such as understanding, reason and sensuality is not, in his view, due to the fact that cognition has become an object. He only sees the numerous contradicting judgments about the functions of knowledge as proof. The general expressions for the established classes of ideas have been opened up; the differences of the individual classes, which have been grasped in terms, form only a necessary correlate of ideas for a subject, which in this case is the principle of the ground of knowledge. The concepts are thus abstracted from the type of what is known: the subject relates to the classes of ideas in the same way as the subject relates to the object.

“Just as the object is immediately posited with the subject [...] and in the same way with the object the subject, and thus being a subject, means just as much as having an object and being an object as much as being recognized by the subject: exactly as it is now even with an object determined in some way or another, the subject is immediately posited as knowing in just such a way . In this respect it makes no difference whether I say: [...] the objects are to be divided into such classes; or: the subject has such different powers of knowledge. "

The subjective correlate of this class is self-confidence.

The world as will and idea

Schopenhauer's epistemology clearly shows his conception of ontology by writing: “... first of all, that object and idea are the same; then that the "being" of the vivid objects is their work ... ". With the statement that objects in space and time, under the principle of reason , are subject to the law of causality applied by the understanding, his criticism of Kant's definition of the thing-in-itself begins ; Schopenhauer sees in Kant's views, purely to grasp the possibility of things of external appearance, their form, therefore only representation of the external world, whereupon Schopenhauer modifies the thesis of the thing in itself according to his conception, the world, in the external appearance as representation, through the Subject conditions, only ascribes purely transcendental ideality and as the core defines the will as an actual thing in itself .

With this, Schopenhauer introduces a conceptual separation of reality - which already includes the word work - and will by naming the understanding as an objectity of the will as the subjective correlate of matter or causality and, according to these findings, his programmatic title The world as will and Concept design.

The center of his dissertation is the world as an idea. In his main work, The World as Will and Imagination , Schopenhauer tries to answer the question of what the world is apart from imagination with his discovery of the will. Schopenhauer tries to show, contrary to the philosophical tradition, that the original place of the will does not lie in the intellect, but that this only forms the objectity of the will. Every action, every movement, every motive and reaction to a stimulus, be it to be blinded by light or pain, as well as the world in general as an idea, he calls the objectification of the will. For Schopenhauer, the non-objectified will represents a blind, ignorant urge to live. Similar to psychology later, Schopenhauer tries to show that “people are not masters of their own house”.

With the complex distinction between imagination and will, Schopenhauer tries to show the irrational as the basic principle of the world. In the break, the denial of desires, the annulment of the individual idea of the world; in the recognition of the formless and ignorant will in humanity, animality and the world, as the same in ourselves. This shows the turning point within his work. Conditioned in the conception of the intellect, nature, Schopenhauer sees nature, in the sense of will, as a condition of an objectivation, like the intellect one such: the will to know. According to Schopenhauer, the intellect is only the instrument of the will. Schopenhauer would like to add a hermeneutics of Dasein to the empirical analysis of the imagination .

Metaphysics and ethics

In his main work, Schopenhauer develops a large-scale system of voluntaristic metaphysics . Schopenhauer is considered a pessimist , his attitude has been compared to that of the Buddha ( all life is suffering ), as it is to be found in Buddhism as the first in the "four noble truths" . Schopenhauer himself writes:

“Awakened to life from the night of unconsciousness, the will finds itself as an individual in an endless and limitless world among countless individuals, all dying, suffering, erring; and as if through an anxious dream he hurries back to the old unconsciousness. "

"So the instruction that gives everyone their life consists in the fact that the objects of their desires are constantly deceiving, swaying and falling, thus bringing more torment than joy, until finally even the whole ground on which they all stand, collapses in that his life itself is destroyed and he receives the final confirmation that all his striving and willing was a wrong, a wrong path [.] "

This overall evaluation corresponds to a criticism of the society of his and past times:

“But in all cases that are not within the scope of the law, man's own ruthlessness towards his own kind becomes apparent, which arises from his limitless egoism , sometimes also from malice. How humans deal with humans, shows z. B. Negro slavery, the end purpose of which is sugar and coffee. "

He analyzes and criticizes the destructiveness of man, the root of which he sees in the blind will, which is inaccessible to the human understanding. Schopenhauer's statements thus become a targeted provocation and he refers to Voltaire and his Candide when he writes:

“But even Leibniz's palpable sophistic proofs that this world is the best of the possible can be seriously and honestly opposed to the proof that it is the worst of the possible. Because “possible” does not mean what one can fantasize about, but what can really exist and exist. Now this world is set up as it had to be in order to be able to exist with precise adversity: but if it were even less bad, it could no longer exist. "

Schopenhauer's justification of his diagnosis, human egoism, lies in subjectivity, which is only given to us directly (cf. theorem on the basis of action ): Everything in the world presents itself to us only as an appearance, is a representation of the intellect, which is essentially cerebral Is a tool that serves the "will". All knowledge is subject to the principle of reason, that is, it is structured according to causal connections. Connected with this is the general fate of change, impermanence, never absolute, ever only relative position of things and our bodies; we are, as it were, trapped in our heads as in a dungeon, similar to Plato's allegory of the cave. Schopenhauer sees his achievement in this evidence. On the liberation of the subject from the rule of blind will, he writes:

"... the will comes to self-knowledge through its objectivation, however it turns out, [becomes] its abolition, turn, redemption possible [.]"

Schopenhauer sees in compassion the recognition of the will of another object (man, animal and nature) as the same in oneself. The individual, which according to Schopenhauer only recognizes his own will, is canceled out as the center. Schopenhauer calls it the realissimum , our reality, which recognizes in other things what we ourselves are not . Schopenhauer, however, is concerned with recognizing not the empirical external reality, the notion that is subject to the principle of reason, but the inner being of people, living beings and things, the 'thing in itself', the will. According to Schopenhauer, the individual, egoistic personality only sees its own will as reality, where external things are only imaginations for it. Only in this way, by negating the will of the other, can it guarantee the affirmation of its own individual will. In his ethics, Schopenhauer is concerned with abolishing the boundary between “I and you”, since there is the same will in everything. Schopenhauer sees in the negation of the will a possibility of overcoming the boundaries of the imagination, thus the boundaries between I and you :

“Since this [the principle of reason] is now the form under which all knowledge of the subject stands, in so far as the latter knows as an individual ; so the ideas will also lie entirely outside its sphere of knowledge as such. So if ideas are to become objects of knowledge; so this can only happen with the abolition of individuality in the knowing subject. [Emphasis in the sentence by the author] "

Influences

Schopenhauer relied, among other things, on Plato , whose theory of ideas forms an essential part in the third book. The work is also largely a modification of Kant's transcendental philosophy . Also influential are z. B. Berkeley , Hume and the scientific knowledge of his time.

In the preface to the second edition, Schopenhauer conducted an ironic polemic against Fichte and Hegel . In his work he repeatedly criticized the views of his contemporaries, speaking of "Windbagei" (with reference to spruce) and " Hegelei ".

Schopenhauer was still significantly influenced by ancient Indian thinking. The monistic tendency of these texts also interested other German intellectuals. Hegel thought Indian thinking was outdated, but Friedrich Schlegel published his work On Language and Wisdom of the Indians in 1808 and August Wilhelm von Schlegel acquired Sanskrit skills in Paris , which led to his appointment in Bonn in 1818. Schopenhauer's closeness to ancient Indian thinking is nonetheless singular. Although he developed his basic system independently of these influences, Schopenhauer had contact with the orientalist Friedrich Majer as early as the end of 1813 . From this he also received a partial translation of the Upanishads , a collection of texts from late Vedic literature, in which the beginnings of the teachings of Brahmanism , Buddhism and Hinduism lie. It was a translation into Latin by the French orientalist Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron from 1801-02, which offers fifty Upanishads from a Persian translation of the 17th century. Schopenhauer later called this anthology "the consolation of his life and death". Schopenhauer also studied other secondary literature, especially articles in specialist journals. Schopenhauer already mentioned the influence of the Upanishads in the preface. The second volume also quotes the translation of the Bhagavad Gita by A. Schlegel published in 1823 . The second edition from 1844 contains considerably more references. His admiration for ancient Indian thought was also reflected in the name of his poodle, which he called Atman (individual self, soul, world soul).

effect

Arthur Schopenhauer's work The World as Will and Idea has left its mark on Richard Wagner's musical and dramatic oeuvre in the field of art : “Your discovery through Wagner is described by many scholars, including the composer himself, as his 'Damascus experience', after which he wasn't the same anymore. [...] He read the work four times within a year, read it again and again for the rest of his life ”. After Wagner got to know the script (mid-1850s), the musical drama Tristan und Isolde and the tetralogy The Ring of the Nibelung (also) led to personal and artistic Schopenhauer reflections.

With the idea of the will, Schopenhauer also left striking traces in the psychology of the early 20th century. Whether, for example, in Freud's sex theory or the 1915 work on instincts and instinctual fates , as well as the implicit outline of a psychology of the unconscious in Schopenhauer's writings, analogies can be found again and again. Freud wrote in 1917 “Well-known philosophers are to be cited as predecessors, above all the great thinker Schopenhauer, whose unconscious 'will' is to be equated with the psychological instincts of psychoanalysis.” Alfred Adler later spoke in his lectures of people having their own goal , the will explained by feelings of inadequacy and thus coined the term inferiority complex . Finally, CG Jung , inspired to read Far Eastern literature by Schopenhauer, wrote his theses on the collective unconscious . Jung repeatedly referred to Schopenhauer in his writings, allowed him to flow into his treatises and even spoke at one point of psychology as a continuation of the "Schopenhauer legacy".

Schopenhauer's statements about concepts, language and sophism as well as his later writing on Eristic dialectics influenced Ludwig Wittgenstein in his views on language and language games .

Albert Einstein was an avid reader of Schopenhauer's writings from an early age, although there is no evidence that he systematically dealt with his philosophy. However, the following section on the principle of the ground of being is interesting in view of Einstein's physics: “... how past and future (apart from the consequences of their content) are as null and void as any dream, but the present is only the limitless boundary between both is; in the same way we shall recognize the same nullity in all other forms of the principle of grounding and see that, like time, so also space, and like this, so also everything that is in it and time at the same time, thus everything emerges from cause or motives, has only a relative existence, only through and for another, which is similar to it, ie is again only just as existing. "

Text output

Arthur Schopenhauer: The world as will and idea :

- Ludger Lütkehaus (Ed.): Complete edition (both volumes in one), Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag 1998

- Wolfgang Freiherr von Löhneysen (Ed.): Text-critical edition in two volumes. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1996, ISBN 3-458-33573-0 . (exemplary edition in thin print, quotations have been translated, text-critical afterword, index of persons and terms)

- Wolfgang Freiherr von Löhneysen (Ed.): Complete Works Volume I. and II., Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, Volume I: ISBN 3-518-28261-1 , Volume II: ISBN 3-518-28262-X . (Pages identical to the island edition)

- Edition in four volumes, Diogenes Verlag, Zurich

- Volume 1, Part 1 ISBN 978-3-257-20421-6

- Volume 1, Part 2 ISBN 978-3-257-20422-3

- Volume 2, Part 1 ISBN 978-3-257-20423-0

- Volume 2, Part 2 ISBN 978-3-257-20424-7

Secondary literature

Introductions and contributions to Schopenhauer's philosophy:

- Ludger Lütkehaus (Ed.): The book as will and conception: Arthur Schopenhauer's correspondence with Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-40956-3 .

- Volker Spierling : Arthur Schopenhauer for an introduction. Junius Verlag 2002, ISBN 3-88506-631-9 .

- Susanne Möbuß: Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and idea. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-423-30672-0 .

- Rüdiger Safranski : Schopenhauer and the wild years of philosophy. , Hanser, Vienna / Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-446-23582-3 .

- Volker Spierling (Ed.): Schopenhauer in the thinking of the present , Piper Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-492-03131-5

- Dieter Birnbacher (Ed.): Schopenhauer in the philosophy of the present , Königshausen and Neumann Verlag, Würzburg 1996, ISBN 3-8260-1228-3

- Matthias Koßler (Ed.) Schopenhauer and the Philosophy of Asia , Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-447-05704-2

Arthur Schopenhauer: About the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason and other writings:

- Wolfgang Freiherr von Löhneysen (Ed.): Complete Works Volume III., Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-28263-8

Web links

- Arthur Schopenhauer: The world as will and imagination ( Memento from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 11.4 MB)

- The world as will and idea at Zeno.org .

- Broadcast on BR-Alpha: Denker des Abendlandes , Harald Lesch and Willi Vossenkuhl on Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. ( Memento from February 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- Search for the world as will and conception in the German Digital Library

- Search for "The world as will and imagination" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 2, § 6, p. 16

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 2, § 6, p. 16ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , preface, p. 7

- ↑ See WWV Vol. I, § 1, p. 33ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 2, p. 33

- ↑ See WWV Vol. II, § 5, p. 47ff.

- ↑ Susanne Möbuß , Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 61

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 3, p. 35

- ↑ Susanne Möbuß, Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 65

- ↑ Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , p. 27ff.

- ↑ a b On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 3, § 15, p. 39ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 8, § 46, p. 178

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 56ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, Appendix: Critique of the Kantian Philosophy , p. 639

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 8, § 49, p. 181ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 21, p. 69

- ↑ a b On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 21, p. 67ff.

- ↑ a b Susanne Möbuß, Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 41ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 2, p. 33ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 4, p. 42

- ↑ Susanne Möbuß, Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 60ff.

- ↑ On vision and colors, chap. I, § 1, p. 204ff.

- ↑ Susanne Möbuß, Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 69ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 2, p. 34

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, Appendix: Critique of the Kantian Philosophy , p. 587ff.

- ↑ Susanne Möbuß, Schopenhauer for beginners: The world as will and imagination , p. 58ff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 22, p. 352

- ↑ Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , p. 53ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 19, p. 46.

- ↑ WWV vol. I, chap. 3, p. 39ff.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason , p. A 369

- ↑ Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason , p. A 383

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 1, p. 23ff.

- ↑ Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , p. 54ff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 14ff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 22, p. 352ff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 1, p. 23fff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 22, p. 357

- ↑ Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , p. 55

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 1, p. 11ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 3–5, p. 35f.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 18, p. 43.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 19, p. 44ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 21, p. 68ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 3, p. 40

- ↑ a b WWV vol. II, chap. 4, pp. 66-70 praedicabilia a priori

- ↑ a b c About the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 35, p. 157

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 48

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, pp. 48-49

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 59

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 58

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 61

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 59f.

- ↑ a b WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 60

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 50

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 58ff.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I Appendix: Critique of the Kantian Philosophy , p. 635

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 63ff.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 64.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 14, p. 115

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 26, p. 196

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 63

- ↑ a b On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 61

- ↑ WWV vol. I, chap. 4, p. 60

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 4, § 20, p. 60ff.

- ↑ a b c WWV vol. II, chap. 4, p. 58

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 5, p. 44ff.

- ↑ See Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction, pp. 27ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , Chapter 5, § 26, p. 121

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 3, p. 36ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 36, p. 158

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 38, p. 160

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 37, p. 159

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 3, § 15, p. 39.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 3, § 15, p. 40.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 39, p. 160ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 6, § 36, p. 158.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 7, § 41, p. 168ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 7, § 42, p. 171ff.

- ↑ On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason , chap. 8, § 41, p. 170

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 5, p. 45

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 5, p. 46

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 7, p. 66ff.

- ↑ See WWV Vol. I, § 5, p. 48

- ↑ See WWV Vol. I, § 3, p. 41

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 17, p. 151

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 18, p. 158ff.

- ↑ See Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , pp. 97f.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 17, p. 155ff.

- ↑ Rüdiger Safranski, Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy , p. 306

- ↑ So z. B. Herman J. Warner: The Last phase of Atheism , in: Christian Examiner 78 (1865), pp. 78-88, here especially 79-86. On this reception context cf. Christa Buschendorf's general overview: “The High Priest of Pessimism”: Schopenhauer's reception in the USA , American studies 160, Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2008.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 46, p. 733

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 46, p. 735

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 46, p. 740

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 46, p. 747

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 50, pp. 821f.

- ↑ See Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction , pp. 33f.

- ↑ WWV vol. II, chap. 50, p. 825

- ↑ Rüdiger Safranski, Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy , p. 439

- ↑ See Volker Spierling, Schopenhauer for an introduction, pp. 85f.

- ↑ WWV Vol. I, § 30, p. 246

- ↑ MK Nicholls: The Influences of Eastern Thought on Schopenhauer's Doctrine of the Thing-in-Itself. In: C. Janaway (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Schopenhauer. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-521-62106-2 , pp. 171-212.

- ↑ W. Halbfass: Schopenhauer in conversation with the Indian tradition. In: V. Spierling (Ed.): Schopenhauer in thinking of the present. Munich / Zurich 1987, pp. 55-70.

- ↑ Michael Eckert: Aesthetic transitions in metaphysics and mysticism. Buddhist influences in Schopenhauer's philosophy. In: Prima Philosophia. (Cuxhaven) 5, pp. 41-59

- ↑ Peter Abelson: Schopenhauer and Buddhism. In: Philosophy East and West. 43/2 (1993), pp. 255-278.

- ↑ Arati Barua (Ed.): Schopenhauer and Indian philosophy. A dialogue between India and Germany. Northern Book Center, New Delhi 2008, ISBN 81-7211-243-2 .

- ↑ This emphasizes e.g. B. Brian Magee: The Philosophy of Schopenhauer. 2nd Edition. Oxford 1987, pp. 15, 316.

- ↑ Quoted from: The wisdom of the Upanishads. In: Small library of world wisdom. No. 16, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2006, p. 113f.

- ↑ See Nicholls 2000, p. 178.

- ↑ Jonathan Carr: The Wagner Clan. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-455-50079-0 , p. 39.

- ↑ See WWV Vol I, § 44

- ↑ See WWV vol. II, chap. 19th

- ^ Sigmund Freud , Abriß der Psychoanalyse , Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, p. 194

- ↑ Cf. Alfred Adler, Menschenwissenschaften , Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1966, p. 31 u. 41

- ↑ CG Jung , Gesammelte Werke, Volume 15 On the Phenomenon of Spirit in Art and Science , Walter Verlag 1971, p. 97 (accessed on June 29, 2014)

- ↑ See WWV Vol. I, § 9, p. 77

- ↑ Severin Schroeder: Schopenhauer's Influence on Wittgenstein , published in: Bart Vandenabeele (Ed.): A Companion to Schopenhauer. Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons, 2012, 362–384 and Ernst Michael Lange: Wittgenstein and Schopenhauer Junghans, Cuxhaven 1989

- ^ Johannes Wickert: Albert Einstein, Rowohlt, Hamburg 2005, pp. 27f., 34, 103

- ↑ WWV Vol. 1, § 3, p. 36f.