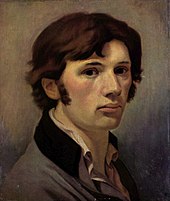

Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel (born March 10, 1772 in Hanover , † January 12, 1829 in Dresden ), von Schlegel since 1814 , usually referred to as Friedrich Schlegel for short , was a German cultural philosopher , writer , literary and art critic , historian and classical philologist . Friedrich Schlegel was, along with his brother August Wilhelm Schlegel, one of the most important representatives of the “Jena Early Romanticism ”. Schlegel's goal, according to his own admission, was the unifying representation of philosophy, prose, poetry, genius and criticism. Important motives for this endeavor were the conceptions of a “progressive universal poetry” , romantic irony and a “new mythology” .

Schlegel is considered a pioneer of language typology and a pioneering indologist without ever being in India. His monograph On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians drew great attention to India. The aphorist Schlegel, "generally regarded as a genius chaot with erratic ideas", inspired the historian Leopold von Ranke , among others . His essayistic work was included in his canon by Marcel Reich-Ranicki .

Life

Childhood, youth, studies

Friedrich Schlegel was born on March 10, 1772 as the tenth child of the Lutheran pastor and poet Johann Adolf Schlegel in Hanover. His father was a pastor at the market church ; the family was artistically and intellectually open-minded. One of his ancestors, Christoph Schlegel (1613–1678), was because of his services as a preacher in Leutschau in 1651 by Emperor Ferdinand III. has been ennobled with the nickname "von Gottleben". The upbringing of Friedrich caused grief for the family: "[...] withdrawn, the child appeared difficult to raise and also of unstable health". Upbringing was first entrusted to his uncle Johann August in Pattensen and then to his brother Moritz in Bothfeld . In 1789 his brother Karl August died in Madras . “At his pleading request” (based on Wilhelm Dilthey ) he broke off an apprenticeship as a businessman with the banker Schlemm in Leipzig and was allowed to prepare for university studies. He moved to Göttingen to live with his older brother August Wilhelm .

He enrolled at the University of Göttingen in 1790 to study law, but turned to classical philology , which he heard from Christian Gottlob Heyne . When his brother moved to Amsterdam as a private tutor in May 1791 , he continued his law studies after a year at the University of Leipzig . Out of reading madness, he occupied himself in the next few years with Hellenism (Greek poets such as Aristophanes , Greek drama , comedies and poetry), Roman civilization, the philosophy of history , contemporary German literature ( Weimar Classics ) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

Leipzig, Dresden

In January 1792 he met Friedrich von Hardenberg (who would later call himself Novalis) know, with whom he had many common interests such as philosophy, history and literary theory, but also Schiller. In the summer of 1793 he gave up his studies because of debt and became a freelance writer. August 1793 he befriended the witty, pregnant widow Caroline Böhmer , daughter of a Göttingen theologian and orientalist. Both friendships shaped his further life decisively, as they supported him in his literary work.

January 1794 he moved to Dresden to his sister Charlotte. There he lived secluded, but got to know Christian Gottfried Körner and published his first work, From the schools of Greek poetry . He mainly dealt with "considerations of metrics " of classical antiquity . Schlegel wrote an essay on Diotima in 1795 , in which he portrayed the literary figure as a priestess and as a Pythagorean woman and described it as an “image of perfect humanity”, as a woman “in whom the grace of an Aspasia , the soul of a Sappho , is expressed with high Wedded independence ”.

In 1795 he made the acquaintance of Johann Friedrich Reichardt , who - like Caroline - was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution , republicanism and democracy . Working on his magazine Deutschland secured his livelihood since 1796. In addition to the political article attempt on the concept of republicanism , Schlegel's sharp criticism of the poems of Friedrich Schiller appeared in it (review of Schiller's Musenalmanac for the year 1796 ).

Jena, Berlin

In July 1796 Schlegel followed his brother August Wilhelm and his wife Caroline to Jena. He was increasingly concerned with philosophy ( Kant , Spinoza ). Here he was strongly influenced by the philosophy of Johann Gottlieb Fichte (cf. his basis for the entire science of science ), with whom he was friends. During his first stay in Jena, the young Schlegel also made fruitful acquaintances with writers of the "older generation": Johann Gottfried Herder , Christoph Martin Wieland and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . In dealing with their works, he developed his famous literary theory.

By the end of 1797, the term romanticism had already taken on many facets for Schlegel. In a letter to his brother August Wilhelm, he wrote: “ I cannot send you my explanation of the word romantic because it is 125 sheets long.” In literature, there should no longer be certain schemes for creating a literary work, but the artist was viewed as a freelance genius . The rule poetics and the demands of the three Aristotelian units of space, time and action lost their importance, rather the novel became the author's subjective playing field. The aim was - according to Schlegel - to present philosophy, prose , poetry, genius and criticism in a way that connects them. These new constellations resulted in a fragmentary character with unfinished storylines. Schlegel wanted to emphasize the process of creation of poetry and meant that the unfinished state of a poem follows the arbitrariness and freedom of the poet.

“The female characters and love in the drama do not have to be attached so externally, but necessarily linked, even allegorically for the transfiguration, the downfall - the reconciliation; d [en] Fight and victory like this prevail as a whole. They must be personified as it were. Yet female characters of doom (like Lady Macbeth) seem questionable. Better all in good principle. [...] (KFSA XVII: 160; xvii, 202, 1808) "

Schlegel further emphasizes the 'indirect religious character of dramatic poetry' (KFSA XVII: 204; xviii, 138, 1823), but writes elsewhere that poetry must be both pagan and Christian, and notes critically that Calderón does not correspond to this ideal (see KFSA XVII: 258; xix, 115, 1811). The drama should also be balanced insofar as 'God and the devil, good and bad principle' (KFSA XVI: 264; ix, 126, 1799–1801) are to be portrayed equally. "

In Germany, the term “ historicism ” appears for the first time in 1797 by Schlegel, referring to “ Winckelmann's historicism” in order to make the “immeasurable difference” between antiquity and the contemporary culture of the 18th century clear. He advocates not looking at antiquity through philosophical glasses, but accepting it in its independence.

Schlegel wrote of " degenerate art " in relation to poetry from late antiquity .

In 1797 he met Friedrich Schleiermacher , the preacher at the Charité Berlin. Schleiermacher and Schlegel lived in a small apartment, read Fichte's science theory and the basis of all science theory together , translated Plato and heatedly discussed the art of living . He also made the acquaintance of Rahel Varnhagen von Ense , Ludwig Tieck , Dorothea Veit , the daughter of Moses Mendelssohn , in the literary salon of Henriette Herz , with whom he lived after her divorce in 1798. This period finds a programmatically exaggerated representation in his novel Lucinde (1799).

In 1798 the Schlegel brothers founded the aesthetically critical magazine Athenaeum . It is considered to be the linguistic organ of Jena early romanticism. Together with Novalis, Friedrich Schlegel developed the fragment into a specifically romantic literary art form in this magazine . Schlegel criticized Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years .

The "romantic flat-sharing community" in Jena

In 1799 the two brothers, August Wilhelm's wife Caroline and Dorothea Veit, lived together for six months - in the back of the house at An der Leutra 5 in Jena . This "romantic flat-sharing community " formed the core of the Jena romanticism. The authors broke with many conventions: For example, they mixed poems and ballads, little fairy tales etc into their novels; they often referred to Goethe's works ( Werther , Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years ). This corresponds to Friedrich Schlegel's concept of “progressive universal poetry”, which not only connects the most diverse genres and areas of knowledge with one another, but also thinks about itself and contains its own criticism. In romanticism, Friedrich Schlegel expanded the concept of irony to include a literary stance that was later referred to as romantic irony .

The group, whose aim was to closely interweave life and literature, received frequent visitors during this time: Schlegel had a close friendship and shared work with Friedrich von Hardenberg ( Novalis ) and Tieck - who appeared with his brother-in-law August Ferdinand Bernhardi Athenaeum . With Novalis, Friedrich Schlegel developed the concept of progressive universal poetry . His roommate from Berlin days, Friedrich Schleiermacher, the Jena-based writer Sophie Mereau (although she is more likely to be assigned to the "Schiller Circle"), her lover and later husband Clemens Brentano and the philosophers Schelling and Fichte frequented the shared apartment. In the nights they discussed literature, art theory and philosophy, during the day they worked on their texts: Friedrich Schlegel on the Lucinde , August Wilhelm and Caroline on the Shakespeare translations.

But this life lasted only a “blink of an eye in world history”. In August 1800 Friedrich Schlegel completed his habilitation at the University of Jena and taught as a private lecturer . A high point in the number of students in Jena came in the 18th century when the university's reputation under Duke Carl August attracted teachers such as Fichte, Schelling, Schiller, Hegel and Friedrich von Schlegel to Jena. Schlegel published his ideas (1800), in which it says: “Only through a relationship to the infinite does content and benefit arise; what does not refer to it is absolutely empty and useless ”. In his conversation about poetry, Schlegel was the first to transfer the term arabesque to literature, in which it describes a form characterized by apparently chaotic, nature-like structures. At the university he gave the lecture on transcendental philosophy (1801). When the shared apartment was dissolved, he left Jena in December 1801. Schlegel took up residence with Tieck in Dresden and both dealt with the publication of Novalis' works Die Lehrlinge zu Sais and Heinrich von Ofterdingen . Schlegel went to Weimar after a stay with Dorothea, who during this time entertained him financially through her literary work (cf. Florentin (novel) ) .

Goethe maintained relations even after the Schlegel broke off with Schiller (1797). He performed Wilhelms Jon (beginning of 1802) and Friedrichs Alarcos (mid-1802), which came to a head when the Kotzebue party, which was in disagreement with both Goethe and the Schlegel brothers, responded with unanimous laughter. Goethe's “Don't laugh!” Was of little help. Due to a lack of psychological motivation, the Alarcos was doomed from the start.

Paris and Cologne

After the Peace of Amiens , Schlegel found himself in Paris studying the art collections, hoping to find a new job or a lost original unit, the golden age . There he lived in a former apartment of the Baron d'Holbach , together with the brothers Boisserée and Alexander Hamilton , who was trapped in Paris as a prisoner of the Napoleonic wars and one of the few Sanskrit experts of his time. He studied Indology , the Persian language as a student of Antoine-Léonard de Chézy and comparative linguistics because he wanted to know which languages are connected with each other; the results of his reflection concerned the first sound shift and the morphological language typology . Schlegel was interested in the paintings of the old masters collected in Paris and founded the magazine Europa ; Heinrich Christoph Kolbe became his employee.

Schlegel was ascribed "an important mediator and mediator role between German and French culture". Perhaps he was pursuing a goal that could only be achieved dialectically: "Through a better knowledge of French culture and its prerequisites, its European supremacy and exemplary character should be broken."

On April 6, 1804, he married Dorothea in the Swedish embassy in Paris , who, as she came from Jewish parents, had to convert to Protestantism beforehand . Shortly afterwards he went to Cologne (because of the medieval art treasures), where he gave lectures at the École Centrale (successor to the old University of Cologne ). He met Ferdinand Franz Wallraf , an obsessed collector of everything connected with Cologne's history. The romanticism at the beginning of the 19th century led to an enthusiasm for medieval buildings in Germany, especially for the great Gothic cathedrals and castles. Schlegel praised the Gothic style epoch in the basics of Gothic architecture in 1804/05 and, like Goethe, spoke of “German architecture”: “There was a reorientation from the philosophical pantheism of Goethe's time to Christian late romanticism , from Baruch Spinoza to Jakob Böhme and the spirit of the Christianity […] ”In 1804 Schlegel visited his brother and Madame de Staël at Coppet Castle . From there he went to Paris, but got sick and went back to Cologne. At the end of 1806 he was a guest at Acosta Castle in Aubergenville with Benjamin Constant and Germaine de Staël for six months . (His wife Dorothea translated her novel Corinne into German.)

In 1808 On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians appeared , a fruit of his Paris studies, in which he presented his romantic ideas about language, religion and culture. It was Schlegel who introduced the term comparative linguistics . Schlegel compared Sanskrit with Latin , Greek , Persian and German and found many similarities in vocabulary and grammar. The assertion of the similarities of these languages is now generally accepted after some adaptations and reformulations. There is less agreement about the geographical region in which this precursor language should be located (see also Out-of-India theory ). Schlegel was also the first to include Sanskrit in the etymology of the term shamanism .

As a convert in Vienna

Schlegel was no longer concerned with Sanskrit, but with Provençal poetry and with the Habsburg Emperor Charles V. His interest in Catholicism grew more and more during his time in Cologne, so that he converted with his wife in Cologne Cathedral in 1808 . He then moved to Prague and Vienna in June, met Johanna Schopenhauer in between and was looking for a publisher to publish all of his works. With a job at Karl von Österreich-Teschen , in whose headquarters he published the Oesterreichische Zeitung in 1809 , and with the Vienna Army Commission, he entered the civil service. In 1810 he became a journalist for the magazine Österreichischer Beobachter ; (the Wiener Zeitung was in Napoleon's hands). He made the acquaintance of the historian Joseph von Hormayr , Klemens Maria Hofbauer , who dealt with religious renewal in Vienna, the painter Ludwig Ferdinand Schnorr von Carolsfeld , the politician Friedrich von Gentz and the writer Theodor Körner . During the 5th coalition war he lived in Pest for a short time and learned Hungarian . After the Peace of Schönbrunn he went back to Vienna.

In 1810 he gave lectures on "Modern History" and in 1812 lectures on the "History of Old and New Literature", which he lectured in the dance hall of an inn. Joseph von Eichendorff was present and wrote «The first lecture of Schlegel (history of literature, 12 guilders redemption coupons per ticket) in the dance hall of the Roman emperor. Schlegel, all black in shoes, reading on a rise behind a table. Heated with fragrant wood. Big audience. In front a circle of ladies, Princess Liechtenstein with her princesses, Lichnowsky, etc. 29 princes. Downstairs there was a large crowd of equipages, like at a ball. Very brilliant. " In 1812 he founded the magazine Deutsches Museum and reported on Karlstein Castle and Rudolfine art. In 1813 he made the acquaintance of the statesman Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein .

In 1814 Pius VII appointed him " Knight of the Papal Order of Christ ". From that time on, he used his noble title, which the family had not used for a century. Even before the Congress of Vienna he dealt with the constitution of Germany and Austria after Napoleon. Even after Jakob Bleyer , his role was more significant and far-reaching than was commonly assumed. Ernst Behler said: "Above all, it was important for him to insert two favorite ideas into the future German constitution, which he called the citizenship of the Israelites and the restoration of the Catholic Church in Germany ." He pointed out that Jews should carry out all civil duties, especially military service , and they could no longer be denied civil rights . From 1815 to 1818 he was an Austrian Legation Councilor at the Bundestag in Frankfurt .

In 1818 he made a trip to the Rhine with August Wilhelm, who had become the holder of the first professorship for Indology in Germany at the University of Bonn . He had letters for the sentence of the Indian Devanagari alphabet made in Paris in order to print the first Sanskrit texts in Europe. The first book was the Bhagavad Gita in 1823 with a Latin translation by August Wilhelm. In 1819 he accompanied Emperor Franz II (HRR) and Klemens Wenzel Lothar von Metternich to Rome, where his wife and their two sons, Philip and Johannes Veit , lived.

With Concordia , Friedrich founded another magazine in 1820. Adam Müller von Nitterdorf , Franz Baader , Joseph Görres and Zacharias Werner became employees ; the Catholic aspect was clearly in the foreground. He condemned the modern age as a whole and pleaded for the restoration of the medieval class order . “During his lifetime, Schlegel was seen more and more as a representative of the Catholic party and papal interests in Germany.” The Concordia met with rejection, not only from Protestants and liberals, but also from August Wilhelm and his surroundings. The sixth and last issue came out in 1823. Schlegel made several trips to Feistritz Castle (Ilz) . The conflict that arose between the brothers was no longer bridged and in 1828 led to August Wilhelm's public distancing from Friedrich. Schlegel's effect was more and more limited to a narrow circle of like-minded people. He became a mystic and engaged in telepathy .

After giving lectures on the Philosophy of Life (1827) and the Philosophy of History (1828) in Vienna , he traveled to Dresden in 1828, where he prepared lectures on the philosophy of language and the word . Friedrich von Schlegel died completely unexpectedly of a severe stroke in his inn. He is buried on January 14th in the Old Catholic Cemetery in Dresden.

Schlegel's philosophy

- “It is equally deadly to the mind to have a system and not to have one. So he will have to decide to combine both. "

- “One can only become a philosopher, not be it. As soon as you believe you are, you cease to be. "

- (with reference to Fichte :) "The world is not a system , but a history from which of course laws can follow."

- Truth is the "indifference [...] two opposing errors".

- "Our knowledge is nothing, we only listen to the rumors."

Knowledge is not everything - so the short formula of the romantic criticism of the Enlightenment . Reason is a dimension that the wholeness of the world cannot describe on its own. One cannot grasp the story correctly if one does not encounter it poetically and intuitively and also tries to empathize with the emotional world of the observed time. The concentration on the rational misses the organic, the becoming and passing away in a historical culture. These thoughts brought into the debate by Hamann ( Socratic Memories ) and Herder ( Also a Philosophy of History for the Education of Humanity ) were taken up in Romanticism and, along with others, reworded by Novalis ( Pollen ) and Schlegel.

In the Cologne “Philosophical Lectures” (1804–1806) Schlegel formulated the idea of the “law of the eternal cycle” founded in the philosophy of India, with which he criticized the linear progression of the Enlightenment:

“Philosophically, one can set up as a general law for history that the individual developments form opposites according to the law of jumping into the opposite that applies to them, that they break up into epochs, periods, but the whole of the development forms a cycle, returns to the beginning; a law that is applicable only to totalities. "

For Schlegel there are no definitive truths that, as the Enlightenment imagined, crystallized in the light of reason. History is a never-ending process of growing and fading. The world cannot therefore be viewed statically, but science has to deal with becoming. The primary science is therefore history and not philosophy.

“If history is the only science, one might ask how does philosophy relate to it? Philosophy itself must be historical in spirit, its way of thinking and imagining must be everywhere genetic and synthetic; this is also the goal that we set ourselves in our investigation. "

He rejected the idea of a truth as the correspondence of things with the ideas in the mind, because then the ideas would have to be just as fixed as things and would lose the freedom of thought.

“There is no true statement, because a person's position is the uncertainty of floating. Truth is not found, but produced. It is relative. "

That is why he also rejects Fichte's subjective identity of the self in himself. It is not about the relationship between the knowing I and a not-I facing it, but about a context of meaning in which the relationship of the finite I with the infinite in which it participates is established. Freedom arises precisely from the fact that the imagination is not tied to a material causal connection. This freedom is most strongly expressed in poetry.

“The own purpose of the imagination is inner, free, arbitrary thinking and poetry. In poetry she is really the most free. "

In view of the limits of human knowledge, which the absolute cannot grasp, Schlegel saw a way out in poetic literature, which opens up a way to get as close as possible to the transcendent, not concretely graspable divine.

“But because all knowledge of the infinite, like its object, can always be infinite and unfathomable, i.e. only indirect, symbolic representation is necessary in order to be able to recognize in part that which cannot be recognized as a whole. What cannot be summarized in a concept can perhaps be represented by a picture; and so the need for knowledge leads to representation, philosophy leads to poetry. "

Philosophy and poetry are not opposites, but rather need to be complemented by one another:

“They are inextricably linked, a tree whose roots are philosophy, whose most beautiful fruit is poetry. Poetry without philosophy becomes empty and superficial, philosophy without poetry remains without influence and becomes barbaric. "

Political philosophy

In the early phase of his philosophizing, Schlegel, like other romantics, was under the influence of the French Revolution . In his attempt on the concept of republicanism , he criticizes the definition of republicanism in Kant's book On Eternal Peace or goes far beyond this definition. Republicanism must necessarily be democratic. Schlegel demands that the “empirical will”, that is, the “will of the majority” should apply as a surrogate of the general will ”, since the a priori“ absolutely general will [...] cannot occur in the area of experience ”. In special cases it also legitimizes the insurrection , i.e. the uprising or the revolution: It could be thought that in certain situations the "constituted power will be considered de facto annulled and the insurrection should therefore be allowed to every individual", for example if a Dictator usurped power permanently or if the constitution is destroyed. In doing so, he implicitly turns against the idea developed only a short time later by Kant (in the Metaphysik der Sitten 1797) that it is a crime to even temporarily override laws legitimized by the general will of the people.

After the Restoration of 1815, Schlegel took a much more conservative position in his function at the Austrian court: in his essay Signature of the Age (1820) he criticized the twin evils of idealism and British-American parliamentarism. He calls for an organic-corporatist Christian state with the family as the center, as Hegel envisions in his philosophy of law. However, he attacks Hegel himself from the right and accuses him in 1817 of having created "an actual deification of the negative spirit" with his system, "that is, in fact, philosophical Satanism ."

Works

- On the aesthetic values of Greek comedy. 1794.

- About the Diotima. 1795.

- Attempt on the concept of republicanism. 1796.

- Georg Forster . 1797. ( full text )

- About the study of Greek poetry. 1797. ( full text )

- About Lessing. 1797. ( full text )

- Critical Fragments. ("Lyceums" fragments), 1797. ( full text )

- Fragments. ("Athenaeum" fragments), 1798. ( full text )

- History of the poetry of the Greeks and Romans 1798.

- About Goethe's master. 1798. ( full text )

- Lucinde . 1799. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- About philosophy. To Dorothea. 1799. ( full text )

- Ideas. 1800. ( full text )

- Conversation about poetry. 1800. ( full text )

- About the incomprehensibility. 1800. ( full text )

- Characteristics and reviews. 1801.

- Transcendental philosophy. 1801.

- Alarkos. 1802.

- Trip to France. 1803. ( full text )

- Contributions to the history of European literature. 1803. ( full text )

- Paris news. 1803. ( full text )

- Basic features of Gothic architecture. 1804/1805.

- About the language and wisdom of the Indians . 1808. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- German museum. (As ed.) 4 vols. Vienna 1812–1813, Camesina> Zeitschriften Literatur .

- History of ancient and modern literature. Lectures, 1815.

Work editions:

- All works. 10 vols., Vienna 1822–1825

- All works. 2nd original edition, 15 volumes, 4 supplement volumes, Vienna & Bonn 1846

- Jakob Minor : Friedrich Schlegel. His prosaic youth writings 1794–1802. 2 vols. Konegen, Vienna 1882.

- Ernst Behler, Jean-Jacques Anstett, Hans Eichner (eds.): Friedrich Schlegel. Critical edition of his works. 35 vol. (Not yet completed; website ), Paderborn et al. 1958 ff.

- Dept. 1: Critical new edition

- Section 2: Writings from the estate

- Dept. 3: Letters

- Dept. 4: Editions, Translations, Reports

- From the romantic mind. Selected essays. Edited by Renate Riemeck . Wedel 1946 (= master of the small form. Volume 1).

- Ernst Behler (Ed.): Friedrich Schlegel. Critical writings and fragments. Study edition. 6 vols., Ibid. 1988;

- Wolfgang Hecht (Ed.): Friedrich Schlegel. Works. 2 vol., Berlin / Weimar 1980.

- Writings on Critical Philosophy 1795–1805 . With an introduction and notes ed. by Andreas Arndt and Jure Zovko, Meiner, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7873-1848-3 ( content and introduction (PDF; 389 kB), review ; PDF; 94 kB)

- "Athenaeum" fragments and other early romantic writings. Philipp Reclam jun., Ditzingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-15-019525-3 .

estate

- From 1822 to 1825 Schlegel dedicated himself to the edition of his Complete Works . Windischmann published the "Philosophical Lectures" of his late friend Schlegel.

- Part of the estate was handed over to the Historical Archive of the Archdiocese of Cologne in 2009 , including manuscripts, texts and drafts with handwritten additions. The partial estate is the property of the Görres Society for the Care of Science and comprises 3,321 pages.

literature

(Chronologically)

- Josef Körner (Hrsg.): Crisis Years of Early Romanticism. Letters from the Schlegelkreis. Three volumes (volumes 1 and 2: Rohrer, Brünn, Vienna, Leipzig 1936/37; volume 3: Francke, Bern 1958).

- Curt Grützmacher : Athenaeum . A magazine from 1798–1800 by August Wilhelm Schlegel and Friedrich Schlegel . Selected and edited by Curt Grützmacher. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1969.

- Antoine Berman : L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin. Paris, Gallimard 1984, ISBN 978-2-07-070076-9 .

- Gerhard Kraus: Natural poetry and art poetry in Friedrich Schlegel's early work. Erlangen 1985, ISBN 3-7896-0164-0 .

- Manfred Engel : The novel of the Goethe era . Vol. 1: Beginnings in Classical and Early Romanticism: Transcendental Stories. Stuttgart, Weimar 1993, pp. 381-443, ISBN 3-476-00858-4 .

- Thomas Brechenmacher : SCHLEGEL, (Karl Wilhelm) Friedrich von. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 241-250.

- Dirk von Petersdorff : Mystery Speech. To the self-image of romantic intellectuals. Tübingen 1996, ISBN 978-3-484-18139-7 .

- Albert Meier: "Good dramas have to be drastic": For the aesthetic rescue of Friedrich Schlegel's Alarcos. In: Goethe Yearbook VIII (1996), pp. 192-209.

- Werner Hamacher : The suspended sentence. Friedrich Schlegel's poetological implementation of Fichte's absolute principle. - In: Werner Hamacher: distant understanding. Frankfurt 1998, pp. 195ff., ISBN 3-518-12026-3 .

- Friederike Rese: Republicanism, Sociability and Education. On Friedrich Schlegel's “Experiment on the Concept of Republicanism”. In: Athenaeum. Jahrbuch für Romantik 7 (1997), pp. 37-71.

- Peter Schnyder: The magic of rhetoric. Poetry, philosophy and politics in Friedrich Schlegel's early work. Schöningh, Paderborn [et al.] 1999, ISBN 3-506-77956-7 .

- Berbeli Wanning: Friedrich Schlegel. An introduction. Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-88506-306-9 .

- Ernst Behler : Friedrich Schlegel. With testimonials and photo documents . 7th edition Hamburg 2004 (RoRoRo picture monographs), ISBN 3-499-50123-6 .

- Franz-Josef Deiters : "Poetry is a republican speech". Friedrich Schlegel's concept of self-referential poetry as the completion of the political philosophy of the European Enlightenment. In: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 81.1 (2007), pp. 3–20; also in: Estudios Filológicos Alemanes 12th ed. Fernando Magallanes Latas. Seville 2006, pp. 107-124.

- Anna Morpurgo Davies (1998) History of Linguistics edited by Giulio Lepschy. Volume IV. Longman. London and New York.

- Jure Zovko: Schlegel, Carl Wilhelm Friedrich von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , pp. 40-42 ( digitized version ).

- Jens Szczepanski: Subjectivity and Aesthetics: Counter-discourses on the metaphysics of the subject in aesthetic thinking in Schlegel, Nietzsche and de Man , transcript, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-709-7

- Ulrich Breuer: Friedrich Schlegel. In: Wolfgang Bunzel (ed.): Romanticism. Epoch - authors - works. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-22073-1 , pp. 60-75.

- Johannes Endres (ed.): Friedrich Schlegel-Handbuch. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-476-02522-7 .

- Alexander Muschik: Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) and Gothicism - Romantic construction of history under the sign of the Nordic Renaissance , in: Martin Göllnitz et al. (Ed.): Conflict and Cooperation. The Baltic Sea as a space for action and culture , Peter Lang, Berlin 2019, ISBN 9783631785836 , pp. 153–170.

- Marcus Böhm: Dialectics in Friedrich Schlegel: between transcendental knowledge and absolute knowledge . (Dissertation, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, 2018). Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2020. ISBN 978-35067-0306-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich Schlegel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich Schlegel in the German Digital Library

- Works by Friedrich Schlegel at Zeno.org .

- Works by Friedrich Schlegel in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Friedrich Schlegel in the Internet Archive

- Friedrich Schlegel: Schools of Greek poetry. 1794; in the project "Poetry Theory"

- Friedrich Schlegel: History of the poetry of the Greeks and Romans. 1798; in the project "Poetry Theory"

- Literature review: Athenaeum fragments - Selected Athenaeum fragments by Friedrich Schlegel

- Allen Speight (2007): Friedrich Schlegel Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Essays on Schlegel

- Reinhard Markner: Fractal Epic. Friedrich Schlegel's answers to Friedrich August Wolf's Homeric questions (PDF file; 255 kB)

- Günter Oesterle: Friedrich Schlegel in Paris or the romantic counter-revolution (PDF file; 156 kB)

Friedrich Schlegel Society

- Friedrich Schlegel Society

- Athenaeum - yearbook of the Friedrich Schlegel Society

Remarks

- ^ Anna Morpurgo Davies (1998) History of Linguistics , pp. 67, 71, 75.

- ↑ Birgit Rehme-Iffert (2001): Skepticism and Enthusiasmus. Friedrich Schlegel's basic philosophical thought between 1796 and 1805 .

- ↑ Joachim Thielen (1999): Wilhelm Dilthey and the development of historical thinking in Germany in the late century .

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki : Friedrich Schlegel - The romantic prophet in: The Lawyers of Literature dtv 1996, pp. 65–82.

- ↑ Joachim v. Roy: The Schlegel de Gottleben family. Article from March 2, 2013 in the forum heraldik-wappen.de . Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ↑ Klaus Peter (1978) p. 20 .; Ernst Behler (1966) p. 14.

- ↑ CF Gellert's correspondence: 1764–1766 ( [1] )

- ^ Lu: Schlegel, Karl August Moritz . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 31, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1890, p. 389 f.

- ^ Imhoff India Driver: a travel report from the 18th century in letters and pictures by Gerhard Koch

- ↑ Wulf Segebrecht: What Schiller's bell struck. From the echoes and echoes of the most parodied German poem. Hanser, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-446-20593-4 .

- ↑ Birgit Rehme-Iffert (Tübingen) Friedrich Schlegel on emancipation, love and marriage

- ↑ Ernst Behler (Ed.): Friedrich Schlegel: Studies of the Classical Antiquity (= Critical Friedrich Schlegel Edition, Vol. 1 Section 1), Paderborn 1979, p. 115; see. S. CXLIX-CLII.

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Attempt on the concept of republicanism . (1796) In: Critical writings and fragments . (1794-1797) Volume 1, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 1988, page 55

- ↑ 125 sheets correspond to 2000 pages. Letter of December 1, 1797 in Ernst Behler u. a. (Ed.): Friedrich Schlegel. Critical Edition Vol. XXIV, p. 53

- ↑ The Schlegel brothers and the 'romantic' drama. A typological comparison of the theory and practice of the 'romantic' drama in Germany and Spain by Beatrice Osdrowski, p. 41.

- ^ The Schlegel Brothers and the 'romantic' drama. A typological comparison of theory and practice of the 'romantic' drama in Germany and Spain by Beatrice Osdrowski, p. 43.

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel: To Philology I . In: Critical Schlegel Edition . Paderborn 1981, XVI, pp. 35-41.

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel uses in his essay On the Study of Greek Poetry (1797) "degenerate" several times in a culture-critical sense: "The degenerate taste, on the other hand, will tell science its own wrong direction instead of receiving a better one from it." ". the return of degenerate art to real, from the depraved taste at the right seems to be just a sudden jump [...]" archive link ( memento of the original December 22, 2013 Internet archive ) Info: the archive link is automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

-

↑ Gerd Fesser : Classic City: Jena's golden years . In: Die Zeit , April 28, 2008. Retrieved on July 1, 2012. “The Schlegels and their friends - all of them young and wild, Jena Boheme. For nights they argued about art, morals, and politics. They put on small plays, hiked together, dressed in the fashion of the French Empire. They made fun of Schiller's ballads, their song from the bell was an involuntary satire. They had nothing but ridicule for the flat rationalism of the popular enlightenment or the normative poetics of the Weimar Classic. Schiller did not hide this: in Caroline he saw a "Madame Lucifer" and in Friedrich Schlegel only an "immodest, cold joke".

August Wilhelm Schlegel translated Shakespeare, Novalis, in search of the blue flower, wrote his avant-garde romance novel Lucinde , Tieck fantastisch-demonische Märchen , on his Heinrich von Ofterdingen , Friedrich Schlegel, inspired by Dorothea and Caroline . Little Jena had become an intellectual metropolis. " - ↑ Gerd Fesser : Classic City: Jena's golden years . In: Die Zeit , April 28, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Ideas , in: Critical Friedrich Schlegel Edition (KA), ed. by Ernst Behler with the assistance of Jean-Jacques Anstett and Hans Eichner. Paderborn, Munich, Vienna, Zurich, Darmstadt 1958 ff. KA 2, 256

- ↑ Tabula Rasa

- ↑ p. 210

- ↑ L. Zahn: History of Art . Bertelsmann, Gütersloh (no year), p. 342 f.

- ↑ Goethe and the Age of Romanticism by Walter Hinderer

- ^ Günter Oesterle: Friedrich Schlegel in Paris or the romantic counter-revolution (October 8, 2005). In: Goethezeitportal. [2]

- ^ Anna Morpurgo Davies (1998) History of Linguistics , p. 61.

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/schlegel/

- ↑ Erich Kasten (ed.): Shamans of Siberia. Magician - Mediator - Healer , pp. 24, 172-187. For the exhibition in the Linden Museum Stuttgart, December 13, 2008 to June 28, 2009, Reimer Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-496-02812-3 .

- ^ Anna Morpurgo Davies (1998) History of Linguistics , p. 81.

- ^ Oesterreichische Zeitung . (Published in the headquarters of Archduke Carl by Friedrich von Schlegel). Sl 1809. (full text) .

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ Ernst Behler (1966) Friedrich Schlegel, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1966, p. 110.

- ↑ Ernst Behler (1966) p. 120.

- ↑ Ernst Behler (1966) pp. 123-124.

- ↑ Volker Zotz : On the blissful islands . Theseus, 2000, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Klaus Peter: Friedrich Schlegel . Realities for literature. Metzler Collection, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-476-10171-1 , p. 82.

- ↑ Klaus Peter (1978) Friedrich Schlegel , pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Ernst Behler, op.cit., P.137.

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel: Philosophy of Life. In fifteen lectures given in Vienna in 1827, KA 10, pp. 1–308

- ↑ Friedrich von Schlegel: Philosophy of History: held in eighteen lectures in Vienna in 1828, Volume 1 = KA Volume 9

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Philosophical lectures in particular on the philosophy of language and the word. Written and presented at Dresden in December 1828 and in the first days of January 1829, KA 10, pp. 309-534

- ↑ Fragment No. 53 from: Friedrich Schlegel: Fragments . First published in: Athenaeum , Vol. 1, 2nd piece, 1798. Today in: Critical Friedrich Schlegel Edition . First section: Critical new edition, Volume 2. Munich, Paderborn, Vienna and Zurich 1967, pp. 165–256 ( online edition ).

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Fragments at the end of the Lessing essay , No. 135. In: Ders. Writings on Critical Philosophy 1795-1805 . Edited by Andreas Arndt and Jure Zovko. Hamburg (Felix Meiner) 2007, p. 126 [239] ( online ).

- ^ Critical Friedrich Schlegel Edition , Volume 12, p. 92.

- ^ History of the poetry of the Greeks and Romans

- ↑ The paragraph is taken from the Wikipedia article: History of Philosophy

- ^ Friedrich von Schlegel: Philosophical lectures from the years 1804 to 1806: together with fragments, excellent philosophical-theological content. Volume 3, ed. by Karl Joseph Hieronymus Windischmann , 2nd edition Weber, 1846, 218 ( Google books ).

- ^ Friedrich von Schlegel: Philosophical lectures from the years 1804 to 1806: together with fragments, excellent philosophical-theological content, Volume 3, ed. by Karl Joseph Hieronymus Windischmann, 2nd edition Weber, 1846, 127

- ^ According to Philosophische Lehrjahre (Vol. 18 of the Critical Schlegel Edition), No. 1149, formulated in: Hans Jörg Sandkühler (Ed.): Handbuch Deutscher Idealismus . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, ISBN 978-3-476-02118-2 , p. 350.

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel: Development of Philosophy in 12 Books, in: Critical Edition, ed. von Behler, Volume 12, Schöningh, Munich-Paderborn-Vienna 1964, 359

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel: "History of European Literature", KFSA 11, p. 9

- ↑ Friedrich Schlegel: “History of European Literature”, KFSA 11, p. 10

- ↑ F. Schlegel: Experiment ... , p. 302 f. In: Herbert Uerlings (Ed.): Theory of Romanticism , Stuttgart 2013.

- ↑ Schlegel, Experiment ... , p. 313.

- ^ F. Schlegel: Philosophical lectures from the years 1804 to 1806, Volume 2 , Bonn 1837, p. 497.

- ^ History of the poetry of the Greeks and Romans

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schlegel, Friedrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schlegel, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German cultural philosopher, writer, literary and art critic, historian and classical philologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 10, 1772 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hanover |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 12, 1829 |

| Place of death | Dresden |