Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas (* shortly before or shortly after New Year's Day 1225 at Schloss Roccasecca at Aquino in Italy; † 7 March 1274 in Fossanova also; Thomas Aquinas , "the Aquinas (s) " or only Thomas called; Italian Tommaso d'Aquino ) was an Italian Dominican and one of the most influential philosophers and the most important Catholic theologian in history. He is one of the most important church teachers in the Roman Catholic Church and is known as such by various surnames such as Doctor Angelicus . According to his history of influence in the philosophy of the high Middle Ages, he is one of the main representatives of scholasticism . He left behind a very extensive body of work, which continues to have an impact on Neuthomism and Neuscholasticism up to the present day. He is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church .

Life

Thomas Aquinas was born shortly before or shortly after New Year 1225 in Roccasecca Castle, 9 km from Aquino, as the seventh child of Count Landulf of Aquino (* 1185), Lord of Loreto and Belcastro , and Donna Theodora, Countess of Teate from the Caraccioli (1183–1255), born to the Neapolitan noble family. At the age of five he was sent to the Benedictine monastery of Montecassino as an oblate , where Sinibald, his father's brother, was abbot . Thomas' family followed the tradition of giving the youngest son in the family to a ministry. It was in the family's best interests that Thomas succeeded his uncle. From 1239 to 1244 he studied in the Studium Generale of the University of Naples . In 1244 he joined the Dominicans against the will of his relatives , who had been founded as a mendicant order in 1215 . In order to remove Thomas from the influence of his parents, the order sent him first to Rome and then to Bologna. On the way there, however, he was attacked by his brothers, acting on behalf of his mother, and brought for a short time to the castle of Monte San Giovanni Campano and then to Roccasecca. His family held him from May 1244 to autumn 1245. With Thomas firm in his resolve to remain a Dominican, the family gave in and allowed him to return to the Dominican convent in Naples.

At the University of Paris he studied from 1245 to 1248 with Albertus Magnus , whom he then followed to Cologne . From 1248 to 1252 he was a student and assistant to Albertus there. From 1252 he was back in Paris, where he held his first own courses on the sentences of Petrus Lombardus from 1252 to 1256 as Sentenzenbakkalareus . From 1256 to 1259 he taught in Paris as a master of theology. In 1259 he returned to Italy and taught first in Naples (which, however, is not certain) and then from 1261 to 1265 as a lecturer at the Dominican convent in Orvieto . From 1265 to 1268 he was a master's in Rome, where he began to write the Summa Theologiae . From 1268 to 1272 he taught for the second time as a master in Paris. It was during this time that many of his writings were written, including most of the Summa Theologiae and most of his Aristotle commentaries. In the spring of 1272 he left Paris. From the middle of 1272 to the end of 1273 he taught as a master in Naples.

Judging by the vast amount of his writings, it seems reasonable to believe the testimony of his chief secretary: that Thomas dictated three or four secretaries at the same time.

Thomas died on March 7, 1274 on his way to the Second Council of Lyon in the Fossanova monastery . At one point in the Purgatorium (XX, 69) of his Commedia , Dante indicates that Charles I of Anjou was responsible for Thomas' death - and he follows a rumor, which has since been refuted, that Thomas came from Charles I or on his Was ordered to have been poisoned. Villani (IX 218) shares a rumor ("si dice": "they say") that Thomas was murdered by a doctor of the king with poisoned confectionery. According to this account, the doctor did not act on behalf of the king, but with the intention of doing him a favor because he feared that a member of the dynasty of the Count of Aquino, who rebelled against Charles, should be elevated to the rank of cardinal. In different versions, mostly attributing responsibility to Karl, the rumor of poisoning was also spread in the early Latin and vernacular Dante commentaries that emerged after Dante's death. Tolomeo da Lucca , a former student and confessor of Thomas, speaks in his Historia ecclesiastica only of a serious illness on the journey on arrival in Campania , but offers no indication of an unnatural cause of death.

Pope John XXII. said Thomas canonized in 1323. In 1567 he was raised to the rank of Doctor of the Church . His bones were transferred to Toulouse on January 28, 1369 , where they have rested in the church of the Dominican monastery Les Jacobins since 1974 . From 1792 to 1974 they were buried in the Saint-Sernin basilica .

philosophy

reception

Aristotle

The arguments of Thomas are based to a large extent on the thoughts of Aristotle , which spread again in the High Middle Ages , which he - himself a student of the founder of medieval Aristotelian, Albertus Magnus - passed on in his university work and connected in his works with theology. So he identifies the motionless mover from the physics of Aristotle with God . Nevertheless, in his doctrine of God he works out the meaning of revelation , which remains unattainable for philosophical considerations alone.

John of Damascus

Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus were not the first Catholic Aristotelians. The church father Johann Damaszenus explicitly justified his dogmatics with Aristotle and his method; this happened 100 years before the first Aristotle translation into Arabic. Pope Eugene III. had the works of Damascus translated into Latin. The structure and content of Damascus dogmatics are - alongside other works such as that of Hilarius - the basis for the compilation of authoritative doctrinal statements by Petrus Lombardus . Its so-called libri sententiarum were used as the basis for the basic theological studies and commented on by the master's degree; Many hundreds of these sentence commentaries on the work of the Lombards have survived, including that of Thomas. Damascus is also quoted very often in the Thomasian sum of theology.

Nemesios of Emesa

Thomas Aquinas also frequently quotes the text De natura hominis ( On the nature of man ) by Bishop Nemesius , which he, following the translator Burgundio of Pisa (1110–1193), considers to be a work by the church father Gregory of Nyssa .

Metaphysics and ontology

A core element of Thomistic ontology is the doctrine of analogia entis . It says that the concept of being is not unambiguous, but analogous, that is, the word " being " has a different meaning, depending on which objects it is related to. According to this, everything that is has being and is through being, but it has being in different ways. In the highest and proper way it only belongs to God: only he is being. All other being only has a part in being and according to its essence. In all created things, therefore, a distinction must be made between being ( essentia ) and existence ( esse ); only with God do these coincide.

The distinction between substance and job is important for Thomas' system. He follows the Aristotelian doctrine, according to which the accident has no being of its own, but only a being in the substance. Many scholastics use the phrase "accidens (...) non est ens, sed entis". Many compendia on the Thomas 'sum of theology also use this phrase in their index and refer to similarly named passages in the Thomas' work. Thomas certainly calls accidents ens (secundum quid), even if ens describes the substance in the full sense and most appropriately.

Another important distinction is that of matter and form . Individual things arise from the fact that the matter is determined by the form (see hylemorphism ). The basic forms of space and time are inseparably attached to matter. The highest form is God as the cause ( causa efficiens ) and as the end purpose ( causa finalis ) of the world. The unformed primordial matter, d. H. the first substance, the materia is fine .

In order to solve the problems connected with the development of things, Thomas falls back on Aristotle's terms act and potency . Because there is no (substantial) change in God, he is actus purus , i.e. pure reality.

Epistemology

Among the most important statements of Thomistic epistemology heard their truth definition of adaequatio rei et intellectus , d. H. the correspondence of object and mind .

Thomas differentiates between the "active mind" ( intellectus agens ) and the "receptive or possible mind" ( intellectus possibilis ). The active mind is characterized above all by the ability to abstract universal ideas or generally valid (essential) knowledge from sensory experiences (as well as what has already been spiritually recognized). On the other hand, it is the receptive mind that receives and stores this knowledge.

The background is the theory of ideas , which goes back to Plato , according to which the sensually perceivable individual things owe their existence and their essence to the ideas ( ideae ) by which they are determined. But this background is hardly visible any more. While Thomas did little to criticize Aristotle, he only quotes Plato to criticize him. Thomas even shows distance to the church father Augustine , who is otherwise highly valued by him , insofar as he is “platonismo imbutus” (“wetted by Platonism”).

The epistemology of Thomas Aquinas differs fundamentally from that of Plato. For Plato, the world of objects that can be perceived by the senses is only a very imperfect image of the actual reality behind the things that he illustrates in his allegory of the cave . For Aristotle and Thomas, however, physical existence is a perfection and not a mere image of something higher. It follows that the Platonic theory of ideas can only be applied to a very limited extent, if at all, to the Thomistic theory of knowledge.

The active mind can through abstraction (literally: subtracting) the forms ( formae ) from the individually determined things, their essence or "what" -ness ("quidditas") and in further steps recognize the accidents. The human spirit recognizes God (see below) as the last or first cause of the being and being of things, in whose spirit the eternal ideas are the models for the forms ( formae ) of things.

anthropology

Thomas' anthropology assigns man as a body-spiritual rational being a place between angels and animals . Based on Aristotle's De Anima , Thomas shows that the soul possesses the spirit as power, or rather that knowledge is the form of the soul ( scientia forma animae ), while the soul is in turn the form of the body: this is shown in the formulation anima forma corporis . Because the spirit (“intellectus”) is a simple, not compound substance, it cannot be destroyed and is therefore immortal . Even after separation from the body , the spirit can carry out its main activities of thinking and willing . The reunion with one body to be expected after the resurrection cannot be demonstrated philosophically, but it can be proven theologically.

ethics

In ethics , Thomas combines the Aristotelian doctrine of virtue with Christian-Augustinian knowledge. The virtues therefore exist in the right measure or the balance of irrational opposites. The ethical behavior is characterized by the observance of the rational order ( natural law ) and thus also corresponds to the divine will to law. As a cardinal virtues are called by Thomas prudentia (prudence), iustitia (justice), temperance (moderation) and fortitude (courage). The three Christian virtues of faith , love and hope are to be seen independently of this . ( Although the generic term Christian virtues is used for faith, hope and love , it is more correctly the divine virtues, not in the sense that they are virtues of God, but that God is the object of these virtues: Belief in God, Hope in God, love of God.)

The highest good is eternal happiness , which - in the life beyond - can be achieved through the direct contemplation of God. This shows the primacy of knowledge over will.

Political Philosophy and State Thought

Thomas Aquinas was one of the most influential theorists on medieval state thought. He saw the human being as a social being who has to live in a community. In this community he exchanges ideas with his fellow species, and the divinely willed division of the work takes place .

For the state, he recommends monarchy as the best form of government, because an absolute ruler who is one with himself can bring about more unity than an aristocratic elite. Here, several people have to come to an agreement, which always leads to a compromise, i.e. an adjustment, an adjustment, giving up one's own opinion and conviction. In addition, that which corresponds to nature is always best, and in nature all things have only one highest.

Thomas contrasts monarchy as the best form of government with tyranny , which he describes as the worst of all possible forms of government. He notes that it is easier for an aristocracy to develop into a tyranny than a monarchy.

In order to prevent tyranny, the power of the autocrat must be restricted. Tyranny is nevertheless to be endured at first, since there is a risk of aggravation (e.g. through anomie ) ( 1 Petr 2,14-16 EU ). The tyrannicide is according to the teaching of the Apostles no Heroic ( 1 Peter 2.19 EU ).

So Thomas concludes that it is better to take action against oppression only after a general decision.

Like many state thinkers of the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas draws on the organic comparison to the state structure. Here he sees the king at the head of the state, like God standing at the head of creation. Furthermore, he assumes the role of reason or the soul for the human body, whose limbs and organs represent the population. Based on Aristotle , every single link finds its fulfillment in virtue .

Still, Thomas sees the priesthood above kingship; The Pope, as head of the Church, is therefore above the King in questions of faith and morals. That is why the secular rulers are obliged to shape and enforce their laws in accordance with the dogmatic and ethical guidelines of the church. For example, they must carry out the death penalty for people who have been convicted of heresy by the Church and take military action against groups of heretics such as the Albigensians and Waldensians . The separation of church and state is not possible from this position.

Following the line of thought of Aristotle, Thomas legitimizes slavery from natural law as moral and legal.

theology

Synthesis of ancient philosophy and Christian dogmatics

Thomas claims to give theology the character of a science (see below). On the part of the church, this is seen as one of its essential merits. To clarify the secrets of faith, he draws on natural reason , in particular the philosophical thinking of Aristotle . Thomas resolved the contradictions that existed in his time between the followers of two philosophers: those of Augustine (who emphasizes the principle of human faith) and the rediscovered Aristotle (who starts from the world of experience and the knowledge that builds on it). Thomas tries to show that these two teachings do not contradict each other, but complement each other, that some things can only be explained by faith and revelation, others also or only by reason. His achievement is seen above all in this synthesis of ancient philosophy with Christian dogmatics, which is also of incalculable importance for modern times. But Thomas could not prevent the condemnation of Aristotelianism by the Bishop of Paris Étienne Tempier in 1270 .

Natural theology

In the context of philosophical and natural theology, Thomas Aquinas presented arguments for the fact that belief in the existence of God is not irrational, i.e. that belief and reason do not contradict one another. His Quinque viae (“Five Ways”), presented in his main work, the Summa Theologica (also Summa Theologiae ), Thomas did not initially refer to as “ proofs of God ”, but they can be understood as such, since they present rational reasons for God's existence . The chain of arguments ends with the statement "this is what everyone calls God."

Eucharist

Thomas' theology was also formative for the Catholic teaching of the Eucharist . He applied the concepts of substance and accidents to the events in Holy Mass : while accidents, i.e. H. If the properties of bread and wine are preserved, the substance of the Eucharistic gifts is changed or changed accordingly in the body and blood of the risen Christ , who also consists of soul and body ( transubstantiation ). His strict observation of metaphysical principles is characteristic of the Thomistic teaching of the Eucharist . So he rejects the multilocation. Christ is present in the holy figures in several places. But the place is not the place of Christ (His place is now in heaven ). According to Thomas, the place and time of the sacred figures is still that of the former bread or wine .

hell

In his Summa contra gentiles , Thomas u. a. also looks at purgatory or hell and takes over the view of Augustine. He rejects the doctrine of the restoration of all things at the end of time :

“ ... the fallacy of those who claim that the punishments of the wicked will eventually end. "

However, he introduces a new justification for the assumed infinity and horror of such a punishment, which is supposed to come upon man because of a single wrong decision:

" The size of the punishment corresponds to the size of the sin [...] Now, however, a sin against God weighs infinitely serious, because the higher a person is against whom one sin, the more serious the sin. "

He also argues that the punishments that the wicked must suffer have both a psychological or spiritual side ( distant from God ) and a physical side (physical pain ), so that the wicked are punished twice.

spirituality

Thomas went down in history primarily for his contributions to theology and philosophy. In addition, his work is also valued for its deep piety.

On St. Nicholas Day 1273, according to a report by Bartholomew of Capua, during a celebration of Holy Mass, Thomas is said to have been affected by something deeply touching and then to have stopped all work on his writings. He is said to have responded to the request to continue working with the words:

“ Everything I've written feels like straw compared to what I've seen. "

In hagiography this saying is interpreted as a reaction to an experience of God .

liturgy

His work includes the sequence for Corpus Christi Lauda Sion and the Eucharistic hymns Pange Lingua , whose last two stanzas are often sung independently as Tantum ergo , and Adoro te devote . He was entrusted with the entire constitution of the Corpus Christi office (the texts for mass and breviary ).

The Tantum ergo is often sung in the Catholic Church during Eucharistic adoration .

Trinity

The Trinity or Trinity or Trinity God sees Thomas though as a secret ( mystery ), but it can with the help of God, d. H. biblical revelation can be partially "understood". Accordingly, the one God in three persons ( subsistence ) is one divine nature and therefore equally eternal and omnipotent. According to Thomas, neither the concept of “procreation” with the Son ( Jesus ) nor that of “breath” with the Holy Spirit should be understood in the literal or secular sense . Rather, the second and third person of God is the eternal self-knowledge and self-affirmation of the first person of God, i.e. H. God the Father . Because with God knowledge or will and (his) being coincide with his being, his perfect self-knowledge and self-love is of his nature, thus divine.

Punish

One of the parts of Thomas' teaching that is difficult to understand today is that, in addition to excommunication, he considered the execution of heretics to be legitimate, since he regards their offense as more serious than counterfeiters who were then delivered to death. ( Counterfeiters comparison ) ( Summa theologiae , II-II, q. 11, art. 3). With the sentence “ Accipere fidem est voluntatis, sed tenere fidem iam acceptam est necessitatis (the acceptance of faith is voluntary, the accepted faith is necessary)” he provided the theoretical foundation for the medieval inquisition .

He was also against lending against interest , but had to refrain from a complete interest ban in the course of his economic preoccupation with the subject .

Afterlife

Thomas Aquinas was on July 18, 1323 by Pope John XXII. canonized . His order strove with some success to make his teachings binding. The School of Salamanca made his Summa theologica a teaching material and ensured a Thomas renaissance in the 16th century. His work and his ideas were in 1879 by the encyclical Aeterni Patris of Pope Leo XIII. raised to the basis of Catholic academic education. This narrowing stabilized Roman Catholic teaching for decades . The Second Vatican Council also expressly recommends Thomas as the teacher, according to whose teaching theology and philosophy in the study of future priests have to be guided ( Optatam totius ). The encyclical Fides et ratio of Pope John Paul II and the new canon law have confirmed this recommendation again.

Already around 1300 the Franciscan Johannes Duns Scotus stood up against Thomas and founded the philosophical- theological school of the Scotists , with which the Thomists lived in feud at the universities. Thomas' followers defended Augustine's strict teaching on grace and denied the Immaculate Conception of Mary, mother of Jesus . On the question of the freedom of the Mother of God from original sin , the later church has separated itself from the doubts that are often encountered in the Thomistic school, whereby it remains controversial to what extent Thomas was actually an opponent of dogma .

Also Ramon Llull has spoken out against the thomististische scholasticism and thus indirectly the years of indexing of the works and the persecution of Lullists causes.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century there was, on the one hand, an increased interest in the history of philosophy research into the works of Thomas (e.g. Martin Grabmann ), and on the other hand, in Thomism , Neuthomism and Neuscholasticism, a philosophical development based on his work made (e.g. Konstantin von Schaezler ). In recent times, Josef Pieper has dealt with the doctrine of virtue as well as the philosophy and theology of Thomas in numerous books and lectures. Karl Rahner interpreted Thomas Aquinas on the background of his transcendental theology .

Memorial days

- Catholic: [Transfer of the bones] January 28th ( Obligatory Day of Remembrance in the General Roman Calendar )

- Evangelical: March 8th in the Evangelical Name Calendar of the EKD, January 28th in the Calendar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

- Anglican: January 28th

Works

In contrast to other great philosophers such as Albertus Magnus , who held various offices, Thomas gave himself entirely to science. He created a monumental work that is divided into six categories:

- Writings that were created directly in connection with the lessons:

- Sentence comment

- Quaestiones quodlibetales

- Quaestiones disputatae

- De spiritualibus Creaturis

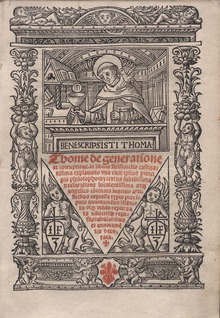

- Comments on the writings of Aristotle:

- to logic

- to physics

- to De caelo et mundo

- on De generatione et corruptione

- to Meteora

- to De anima

- to De sensu et sensato

- to Nicomachean Ethics

- to politics

- to metaphysics

- More comments on:

- Dionysius Areopagita , De divinis nominibus

- Liber de causis

- Boethius , De trinitate

- Boethius, De hebdomadibus

- Smaller pamphlets and polemics like

- About evil

- About lies and error

- About the perfection of the spiritual life

- About the rule of the princes

- About the unity of the intellect against the Averoists

- Compendium theologiae

- Systematic (main) works:

- Commentaries on the Bible

- To Job

- To psalms (Psalm 1–51)

- To Jeremiah

- To the lamentations of Jeremiah

- To Isaiah

- Commentaries on the four Gospels ( Catena aurea )

- Lectures on Matthew and John

- Lectures on the letters of the apostle Paul

- Hymns for the Feast of Corpus Christi

- Sacris solemniis (for Matutin ), with the circuit verses angelicus Panis

- Verbum supernum prodiens (for Laudes ), with the final stanzas O salutaris hostia

- Pange Lingua (at Vespers ) with the final stanzas Tantum ergo , Gotteslob 494

- Lauda Sion ( Sequence of the Mass), German Praise to God (1975) 545

- Adoro te devote , German Praise to God 497

The Summa contra gentiles, and especially the Summa theologica , represent a high point of Thomanian creativity. His work was declared the basis of Christian philosophy by the Roman Catholic Church in the 19th century .

literature

Dictionaries, lexical and bibliographic resources

- Ludwig Schütz : Thomas Lexicon . Collection, translation and explanation of all the works of St. Thomas Aquinas occurring artistic expressions and scientific sayings . Paderborn: Schöningh 2nd edition 1895 (reprint Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog 1964 and other) (x, 889 p.).

- Corpus Thomisticum (Internet library of all texts by Thomas Aquinas, if necessary with translations that enable full-text research; also offers a complete bibliography of Thomas research).

Editions and translations

- Critical edition: so-called Editio Leonina: Sancti Thomae Aquinatis doctoris angelici Opera omnia iussu Leonis XIII. PM edita, cura et studio fratrum praedicatorum , Rome 1882ff.

- The German Thomas edition ( Summa theologica ), transl. By Dominikanern u. Benedictines of Germany a. Austria. Complete, unabridged German-Latin Edition, Graz [a. a.]: Styria, formerly partly in Pustet-Verl., Salzburg, partly in Kerle-Verl., Heidelberg a. Verl. Styria Graz, Vienna, Cologne, 1933ff., 34 vol. (Still unfinished).

- Opera Omnia ut sunt in Indice Thomistico; additis 61 scriptis ex aliis medii aevi auctoribus . Curante Roberto Busa. 7 vols. Frommann-Holzboog. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1980, ISBN 978-3-7728-0800-5 .

- Sum against the pagans ( Thomae Aquinatis summae contra gentiles libri quattuor ), ed. u. trans. by Karl Allgaier, 4 vols., Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchges., 1974–1996, ISBN 3-534-00378-0 .

- Sum of theology, ed. u. trans. by Joseph Bernhart (selection), Kröner Verl., Stuttgart, Vol. 1: God and Creation, ISBN 3-520-10503-9 , Vol. 2: The moral world order, ISBN 3-520-10603-5 , Vol. 3 : Man and Salvation, ISBN 3-520-10903-4 .

- About the ultimate goal of human life. De ultimo fine humanae vitae, text in Latin and German. Ed., Translated and commented by Winfried Czapiewski, Verlag Laufen, Oberhausen 2019, ISBN 978-3-87468-377-7 .

- On moral action: Summa theologiae I - II q. 18–21, Latin-German, commented and ed. by Rolf Schönberger, Reclam, Stuttgart 2001 (Universal Library: 18162), ISBN 3-15-018162-3 .

- Horst Seidl (Ed.): The evidence of God in the 'sum against the heathens' and the 'sum of theology'; Text with translation, introduction and commentary, Latin-German 3. Edition. Meiner, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-7873-1192-0 (translated and edited by Horst Seidl.).

- Quaestiones disputatae , complete edition in German translation, 13 volumes, ed. by Rolf Schönberger, Meiner, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7873-1900-8 (Volumes 1–6: About Truth , Volumes 7–9: About God's Wealth , Volume 10: About the Virtues , Volume 11–12: About Evil , Volume 13: About the Soul ).

- De rationibus fidei , commented on Latin-German Ed. By Ludwig Hagemann u. Reinhold Glei ( Corpus Islamo-Christianum , Series Latina , Vol. 2), CIS-Verlag, Altenberge 1987.

- About the teacher / De magistro. Quaestiones disputatae de veritate, Quaestio XI; Summa theologiae, Pars I, quaestio 117, articulus 1st ed., Trans. u. come over. by Gabriel Jüssen, Gerhard Krieger, Johannes HJ Schneider. With an inlet v. Heinrich Pauli (Philosophical Library 412). Meiner, Hamburg 2006 (lvi, 189 pages), ISBN 978-3-7873-1799-8 .

- From the truth, Latin-German, ed. by Albert Zimmermann . Meiner, Hamburg 1986, ISBN 978-3-7873-0669-5 .

- De principiis naturae - The principles of reality, Latin - German, transl. u. commented by Richard Heinzmann , Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 978-3-17-015633-3 .

- About being and essence, Latin-German, ed. by Horst Seidl . Meiner, Hamburg 1988, ISBN 978-3-7873-0771-5 .

- About being and essence, German-Latin, transl. u. ext. by Rudolf Allers , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1980, ISBN 3-534-00024-2 .

- De ente et essentia / About beings and beings, Latin-German, ed. by Wolfgang Kluxen , Herder's Library of the Philosophy of the Middle Ages Volume 7, Herder, Freiburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-28689-6 .

- About the rule of the princes, trans. by Friedrich Schreyvogl, afterword by Ulrich Matz . [Reprint] Reclam, Stuttgart 1994 (Universal Library: 9326), ISBN 3-15-009326-0 .

- Expositio super librum Boethii De trinitate / Commentary on the Trinity Tract of Boethius, Herder's Library of the Philosophy of the Middle Ages Volume 3, 2 part volumes, Latin-German, ed. by Peter Hoffmann in connection with Hermann Schrödter, Herder, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-451-28504-2 / ISBN 978-3-451-28684-1 .

- Expositio in libri Boetii de Hebdomadibus / Commentary on the Hebdomaden script of Boethius, Herder's Library of the Philosophy of the Middle Ages Volume 18, Latin-German, ed. by Paul Reder. Herder, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-451-30298-5 .

- Quaestio disputata ›De unione Verbi incarnati‹ (“On the Union of the Word Incarnate”). Latin / German. Edited, translated, commented and provided with a reflection on theological and theological history by Klaus Obenauer. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 2011. ISBN 978-3-7728-2563-7 .

- Catechism of St. Thomas Aquinas or Declaration of the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer, Ave Maria and the Ten Commandments of God, Sabat publishing house, Kulmbach 2016, ISBN 978-3-943506-30-3 .

- The prologue of the Gospel of John - Super Evangelium S. Joannis (caput I, lectio I-XI), transl., Introductory and explanatory notes. Wolf-Ulrich Klünker, Latin-German, Free Spiritual Life, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-7725-0855-4 .

- On the unity of the spirit against the Averroists - De unitate intellectus contra Averroistas. On the movement of the heart - De muto cordis, Übers., Einf. And Explanation. Wolf-Ulrich Klünker, Latin-German, Free Spiritual Life, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-7725-0820-0 .

- About the trinity. An interpretation of the book of the same name by Boethius: In librum Boethii de Trinitate Expositio, Transl. And Explanation. Hans Lentz, introductory v. Wolf-Ulrich Klünker, Latin-German, Free Spiritual Life, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 978-3-7725-0850-9 .

- Of the nature of angels. De substantiis separatis seu de angelorum natura, transl., Introductory and explanatory notes. Wolf-Ulrich Klünker. Stuttgart, Verlag Free Spiritual Life, Latin-German, Free Spiritual Life, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 978-3-7725-0919-3 .

- Introductory writings in 5 vol., Latin-German, transl. by Josef Pieper, ed. by Hanns-Gregor Nissing and Berthold Wald, Volume 1: Das Wort. Commentary on the prologue of the Gospel of John, ISBN 978-3-942013-35-2 (2017); Volume 2: The Lord's Supper. The Eucharist tract of the Summa theologiae (III 73-83), ISBN 978-3-942013-36-9 (2018), Volume 3: The Credo. Interpretations of the Apostles' Creed, ISBN 978-3-942013-37-6 (2019), Volume 4: Our Father. Interpretations of the Lord's Prayer, ISBN 978-3-942013-38-3 (2020), Pneuma, Munich 2017-2020.

Bibliographies

- Pierre Mandonnet et Jen Destrez: Bibliography Thomiste , Saulchoir, Kain 1921; 2nd edition revue et complétée par M.-D. Chenu, Vrin, Paris 1960.

- Terry L. Miethe et Vernon J. Bourke: Thomistic Bibliography, 1940-1978 , Greenwood Press, Westport / Connecticut 1980.

- Richard Ingardia: Thomas Aquinas International Bibliography, 1977-1990 , Philosophy Documentation Center, Bowling Green, Ohio 1993.

Introductions

- David Berger : Thomas Aquinas "Summa theologiae" . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2004.

- David Berger: Meeting Thomas Aquinas . Sankt Ulrich Verlag, Augsburg 2002, ISBN 3-929246-77-5 .

- Marie-Dominique Chenu : The work of St. Thomas Aquinas , by the author. u. verb. German edition, transl., delay and Erg. d. Work advice v. Otto M. Pesch, Heidelberg a. a ..: guys u. a. 1960.

- Brian Davies: The Thought of Thomas Aquinas . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1992.

- Paulus Engelhardt : Thomas Aquinas. Directional directions in his work , Dominican sources and testimonials, Vol. 6. St. Benno Verlag, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7462-1810-1 .

- Maximilian Forschner : Thomas Aquinas . CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-52840-6 .

- Richard Heinzmann : Thomas Aquinas. An introduction to his thinking. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a., 1994, ISBN 3-17-011776-9 , uni-muenchen.de (PDF; 18.4 MB).

- Anthony Kenny : Thomas von Aquin , Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1999, ISBN 3-451-04744-6 .

- Volker Leppin : Thomas Aquinas. Approaches to Medieval Thinking . Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-15671-1 .

- Volker Leppin (Ed.): Thomas Handbuch . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016. ISBN 978-3-16-150084-8 (linen) / ISBN 978-3-16-149230-3 (paperback).

- Otto Hermann Pesch : Thomas Aquinas. Limits and greatness of medieval theology. An introduction. 3rd edition Matthias-Grünewald, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-7867-1371-5 .

- Josef Pieper : Thomas Aquinas. Life and work. Topos Taschenbücher Vol. 869, Kevelaer 2014.

- Rolf Schönberger : Thomas von Aquin as an introduction. 4th supplemented edition. Junius, Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-88506-351-3 .

- Eleonore Stump : Aquinas . Routledge, London 2003.

- Jean-Pierre Torrell : Magister Thomas. Life and work of Thomas Aquinas . Herder, Freiburg / B. 1995. ISBN 3-451-23652-4 ; in original French, English Translated as Saint Thomas Aquinas: the person and his work , 2 volumes, Catholic University of America Press, Washington 2nd edition 2005 (the currently authoritative presentation).

- Albert Zimmermann : Reading Thomas . frommann-holzboog, Stuttgart / Bad Cannstatt 2000. ISBN 3-7728-2005-0 .

Special topics

- Gerhard Beestermöller : Thomas Aquinas and the just war. Peace ethics in the theological context of the Summa Theologiae. (Theology and Peace. Volume 4) JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 1990.

- David Burrell: Aquinas: God and Action . University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame IN 1979.

- Leo Elders : The Philosophical Theology of St. Thomas Aquinas . EJ Brill, New York 1990.

- Norman Kretzmann: The Metaphysics of Theism : Aquinas' Natural Theology in Summa Contra Gentiles I / II. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1997/1999.

- Christoph Mühlum: For the good of people. Happiness, law, justice and grace as building blocks of a theological ethics in Thomas Aquinas (Contributiones Bonnenses, Series II, Volume 3). Bernstein-Verlag, Gebr. Remmel, Bonn 2009, ISBN 978-3-9809762-5-1 .

- Walter Patt: Metaphysics with Thomas Aquinas. An introduction. Turnshare, London 2004, ISBN 1-903343-59-3 .

- Wolfgang Kluxen : Philosophical ethics with Thomas Aquinas. 3rd edition. Meiner, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-7873-1379-6 .

- Markus Schulze: Bodily and Immortal. On the display of the soul in the anthropology and theology of St. Thomas Aquinas . Universitätsverlag, Freiburg 1992, ISBN 3-7278-0789-X .

- Markus Stohldreier: On the concept of the world and creation in Averroes and Thomas v. Aquin . A comparative study. Diss. 2008; Munich u. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-640-34740-7 .

- John Wippel: The Metaphysical Thought of Thomas Aquinas : From Finite Being to Uncreated Being. Catholic University of America Press, Washington 2000.

- J. Budziszewski: Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's 'Treatise on Law'. Cambridge University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1-107-02939-2 .

Others

- Yearbook : Doctor Angelicus. International Thomistic Yearbook. Nova et vetera, Cologne-Bonn, 2000–2007 (publication discontinued in 2007).

- Gilbert Keith Chesterton : The Mute Ox. About Thomas Aquinas . Herder Verlag u. a. 1960; New edition included in: St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Francis of Assisi . Nova et Vetera, 2003, ISBN 3-936741-15-8 .

Web links

Texts

Several works

- All works online (Corpus Thomisticum) (Latin)

- Works ( Memento of November 2, 2002 in the Internet Archive ) (UBB Cluj) (Latin)

- Works in english (ed. Joseph Kenny)

- Les œuvres complètes en français de saint Thomas d'Aquin (French)

- Bibliotheca Thomistica IntraText texts, concordances and frequency lists

Theological sums

- Summa Theologiae in the Library of the Church Fathers (Latin-German)

- Summa Theologiae at logicmuseum.com (Latin-English)

- Summa Theologica at newadvent.org (English) or downloadable as a text file: Summa Theologica (English)

- Summa Theologiae , Volumes 1–4 (of a total of 10), translation of various Fathers of the English Dominican Province , London 2nd A. 1920–22 (English)

- Joseph Rickaby: Summa Contra Gentiles in parts

Other individual works

- Sermones, psalms and sentence comments in parts at the Aquinas Translation Project (English)

- Das Beende und das Wesen (De ente et essentia), German (German also about being and being ) (Online at Zeno.org)

- Catena Aurea

Bibliographies

- Works by and about Thomas Aquinas in the German Digital Library

- Th. Bonin: Thomas Aquinas in English Bibliography with many web links to English. Translations

- Enrique Alarcón et al .: Bibliographia Thomistica

- A. Schönfeld SJ: Bibliography and resources ( Memento from December 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

literature

Overviews

- Daniel Kennedy: St. Thomas Aquinas . In: Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

- John O'Callaghan: Saint Thomas Aquinas. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- John Finnis: Aquinas' Moral, Political, and Legal Philosophy. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Further information

- Richard Heinzmann : Thomas Aquinas as the conqueror of the Platonic-Neoplatonic dualism . (PDF; 3.3 MB) In: Philosophisches Jahrbuch , 1986, Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1986, pp. 236–259.

- Richard Heinzmann: At the limit of understanding thinking. On the origin of religious experience in Thomas Aquinas . (PDF; 1.3 MB) In: Armin Kreiner, Perry Schmidt-Leukel (eds.): Religious experience and theological reflection . Bonifatius, Paderborn 1993, pp. 103-111.

- Ralph McInerny : Introduction to Thomas Aquinas . International Catholic University, Notre Dame IN.

- P. Korbinian Thomas Linsenmann: Thomas Aquinas . In: Hexenforschung / Historicum.net

- Link catalog on the subject of Thomas Aquinas at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Thomas Institute (Utrecht)

- Thomas Institute (Cologne)

- In the footsteps of Thomas Aquinas on the pages of the Diocese of Cologne

Individual evidence

- ↑ In addition z. B. also doctor communis , doctor ecclesiae , angelus scholae , pater ecclesiae , lumen ecclesiae , old Augustinus , (rarely) doctor universalis ; see. Friedrich Ueberweg : Outline of the history of philosophy from Thales to the present , Vol. 1, Berlin 1863, p. 97 .

- ^ Dante Alighieri: La Commedia / The Divine Comedy. II, Purgatorio / Läuterungsberg . Italian / German, translated into prose and commented by H. Köhler. Stuttgart: Reclam 2011/2015. P. 397.

- ↑ The reasons given for this vary among the commentators, as Hartmut Köhler points out in the commentary on the passages mentioned (PURG., XX, 67-69) (cf. Dante Alighieri [‹ca.1307-1321›]: La Commedia / Die Götliche Komödie . II, Purgatorio / Läuterungsberg . Italian / German, translated into prose and commented by H. Köhler. Stuttgart: Reclam 2011/2015. P. 396f).

- ^ LA Muratori: Rerum Italicarum Scriptores , Vol. XI, pp. 1168-1169.

- ↑ In the second part 168 times (for comparison: Augustine 1630, Gregory the Great 439, Hieronymus 178, Ambrosius 151), cf. the statistics in Servais-Théodore Pinckaers : The Sources of the Ethics of St. Thomas Aquinas . In: Stephen J. Pope (Ed.): The Ethics of Aquinas . Georgetown University Press, Washington DC 2002, pp. 17-29, here 17f.

- ↑ The reason for this are similarities in terms of content and form with Gregory's De opificio hominis and a tradition in a common codex without author identification; see. in more detail: Emil Dobler: Two Syrian sources of the theological summa of Thomas Aquinas : Nemesios von Emesa and Johannes von Damascus: their influence on the anthropological foundations of moral theology (S. Th. I-II, qq. 6-17; 22– 48), Dokimion vol. 25, Saint-Paul, Freiburg / Switzerland 2000.

- ↑ For example in Petrus Aureoli , Sent. IV, 12, 1, 2 after Aristotle, Metaphysics 1028 a 18.

- ↑ For example: “Unde, secundum philosophum, accidens magis proprie dicitur entis quam ens.” S. Th. Iª q. 45 a. 4 co; “Nam ens dicitur quasi esse habens, hoc autem solum est substantia, quae subsistit. Accidentia autem dicuntur entia, non quia sunt, sed quia magis ipsis aliquid est; sicut albedo dicitur esse, quia eius subiectum est album. Ideo dicit, quod non dicuntur simpliciter entia, sed entis entia, sicut qualitas et motus. “Sententia Metaphysicae lib. 12 l. 1 n.4.

- ↑ On Unity of Mind - De Unitate Intellectu. Lat.- German Translation Wolf-Ulrich Klünker, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 1987 ISBN 3-7725-0820-0 ; P. 29 and P. 39.

- ↑ Thomas orientates himself on Vitruvius , cf. Cornelius Steckner: The city-building king of Thomas Aquinas. Aristotle and Vitruvius, Politics and Urban Development in the Age of the Crusades, in: Aquinas, Vol. 29 (1986) pp. 233-253.

- ↑ H.-D. Wendland: slavery and Christianity . In: Religion in the past and present , 3rd edition, Tübingen, Volume VI, Column 103

- ↑ "omnia quae scripsi videntur michi palee". Thus the report of Bartholomäus von Capua with reference to Reginald von Piperno, the secretary of Thomas, cf. M ..- H. Laurent (ed.): Processus canonizationis Neapoli S. Thomae, Fontes vitae sancti Thomae Aquinatis 4, in: Revue thomiste 38-39 (1933-34), pp. 265-497, 79 , p. 377; C. Le Brun-Gouanvic: Edition critique de l'Ystoia sancti Thome de Aquino de Guillaume de Tocco , 2 volumes, Montréal 1987, 47, p. 347; James A. Weisheipl: Thomas von Aquin , His life and his theology, Graz 1980, 293f; Torrell 1995, 302 / Torrell 2005, 274.

- ↑ Elias H. Füllenbach , Canonization, in: Thomas Handbuch, ed. by Volker Leppin , Tübingen 2016, pp. 426-430.

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas in the ecumenical dictionary of saints

- ↑ English translation by CR Goodwin, Australian Catholic University, 2002, acu.edu.au ( Memento of July 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.0 MB)

- ^ The print editions published before 1971 contain a heavily falsified text; therefore it is necessary to use a critical edition: Editio Leonina vol. XLVIII, 1971 or Opera omnia, ed. by Roberto Busa, Vol. 4, 1980. Cf. Bernhard Stengel: The commentary of Thomas Aquinas on the "politics" of Aristotle , Marburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8288-2757-8 ; Pp. 57-60.

- ↑ Cf. Christian Rode: Review of: Leppin, Volker: Thomas von Aquin. Approaches to Medieval Thinking. Munster 2009 . In: H-Soz-u-Kult , February 16, 2010.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Thomas Aquinas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Thomas Aquinas, Tommaso d'Aquino |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian theologian and philosopher of the Middle Ages |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1225 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Roccasecca , Aquino , Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 7, 1274 |

| Place of death | Fossanova |