Salamanca School

The school of Salamanca is understood to be a legal method of interpreting the late scholastic natural law . The name is derived from the University of Salamanca , where its representatives taught.

In theology , the Dominicans Francisco de Vitoria (1492–1546), Domingo de Soto (1494–1560) and Melchior Cano (1509–1560) were among their most important representatives . The Franciscan Alfonso de Castro (1495–1558) and the Jesuit Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) are also important. Among the canonists are Martín de Azpilcueta (1491-1586) and Diego de Covarrubias y Leyva (1512-1577) emphasized. Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca (1512–1569) distinguished himself as a specialist in Roman law .

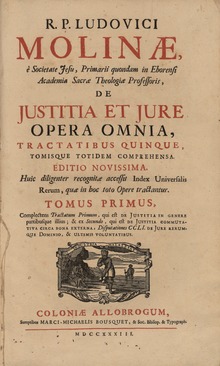

Within the school of Salamanca two schools can be distinguished: the Salmanticens (named after the University of Salamanca) and the Conimbricensians (named after the University of Coimbra in Portugal ). The first direction started with Francisco de Vitoria and culminated with Domingo de Soto. The Conimbricens, on the other hand, were Jesuits who took over the intellectual leadership in the Roman Catholic world from the Dominicans at the beginning of the 16th century . Among them were u. A. Luis de Molina (1535–1600), Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) and (in Italy) Giovanni Botero (1544–1617).

The school of Salamanca gained importance through the development of an "international natural law". Against the background of the conquest of South and Central America by the Spanish and Portuguese, humanism and the Reformation , the traditional conceptions of the Roman Catholic Church came under increasing pressure at the beginning of the 16th century. The resulting problems were addressed by the Salamanca School. Her aim was to harmonize the teachings of Thomas Aquinas with the new economic and political order of the time.

Theory of Law and Justice

The theories of the School of Salamanca herald the end of the medieval legal concept. To a degree that was unusual for Europe at the time, they demand more freedom. The natural rights of man ( right to life , right to private property , freedom of expression , human dignity ) became, in one form or another, the focus of the Salamanca school.

Natural law and human rights

The Salamanca School reformulated the concept of natural law . Since all human beings share in the same human nature, they also all share in the same rights such as equality or freedom . This includes, according to this view, the Native Americans, for example. They too had a right of ownership to their land and had the right to oppose violent proselytizing . These thoughts contradicted the prevailing opinion at the time that the natives had a less developed mind and therefore could not claim the same rights as the Spaniards and other Europeans, but, like children, needed special guidance from the Europeans.

The natural law of the Salamanca School is not limited to individual rights. For example, justice is viewed as a type of natural right that society realizes. According to Gabriel Vázquez (1549–1604), natural law implies an obligation to act in accordance with justice within a society.

sovereignty

The Salamanca School distinguishes between the realm of secular power and the realm of spiritual power. Both were often merged in the Middle Ages , from which teachings such as the divine right of the emperor or the doctrine of the worldly power of the pope were derived. The consequence of the distinction is that the emperor has no legislative power in spiritual matters: he has no power over souls. The Pope, on the other hand, has no legitimate legislative power in worldly matters: he is solely responsible for spiritual matters. From this a limitation of the power of the government was deduced. According to Luis de Molina, a nation is to be understood as a trading company: the rulers would be given power, but were subject to the collective power of all those involved in the trading company. Nevertheless, according to de Molina, the power of society over the individual is greater than the power of a trading company over its members. For, in contrast to the power of individual individuals over themselves in business transactions, the power of a national government arises directly from divine power.

At this time the English monarchy expanded the doctrine of the divine right of the king. According to this doctrine, the king is the only legitimate recipient of divine power. Subjects must therefore obey the orders of the king in order not to thwart the divine plan. In contradiction to this, the supporters of the Salamanca School assumed that the collective people were the only legitimate recipients of divine power. These are then, under certain conditions, passed on to the ruler.

Francisco Suárez goes the furthest on this point in his work Defensio Fidei Catholicae adversus Anglicanae sectae errores . It was the strongest defense of popular sovereignty at the time . Suárez admits that political power does not reside in a single individual. At the same time, however, he also inserts a subtle distinction. The recipient of political power is the people as a whole, not the individual sovereign individuals taken for themselves. This anticipates Jean-Jacques Rousseau's theory of popular sovereignty, according to which the people as a collective group is different from the sum of the individuals of which it is composed.

For Suárez, the origin of the political power of society is contractualist because the community, which is the foundation of a society, is formed through the consensus of the free will of individuals. The consequence of this contractualistic view is that the most natural form of government is democracy . Oligarchy or monarchy are secondary forms of government. They claim to be just forms of government only insofar as they were elected (in a founding act) by the people or at least they have given their consent. According to Suarez, people also have the right to resist an unjust government. Because all people are free and not born as subjects of others.

Ius Gentium and International Law

Francisco de Vitoria developed a far-reaching theory of the ius gentium ; is therefore one of the "fathers of international law". His fundamental idea is that the way people deal with one another not only within a society but also between different societies should be characterized by mutual respect for rights. Therefore, relations between states should not be based on violence but on law and justice.

Vitoria named the two types of law ius inter gentes and ius intra gentes . Ius inter gentes corresponds to today's international law (international law) and was common to all peoples; Ius intra gentes is the right specific to every community.

Just war

For the Salamanca School, war is one of the worst evils of humanity. Therefore, war should only be used to prevent an even greater evil. Diplomatic solutions must be exhausted before a war begins , even if one belongs to the party that is superior in the conflict.

Reasons for a just war are:

- Self-defense as long as there is a realistic chance of success. If there is no prospect of success, a just war in self-defense is unnecessary bloodshed.

- Defense against a tyrant who is either already in power or trying to seize it.

- Punishing a guilty enemy.

Beyond a legitimate reason, a war must also meet the following requirements:

- The martial response must be proportionate to the evil inflicted. Using more force than necessary creates an unjust war.

- The governments declare war on each other. But a declaration of war by a government is not a sufficient reason for a war. If the people are against the war, then the war is illegitimate. The people have the right to remove a government that is making plans for an unjust war or is in the process of carrying it out.

- There are moral limits in war. It is forbidden to attack innocent people or kill hostages.

- Before a war begins, all options for dialogue, such as negotiations, must be exhausted. War is only legitimate as a last resort.

The conquest of South and Central America

During the colonial era , Spain was the only nation where a group of intellectuals was critical of the legality of the conquests.

Francisco de Vitoria began his analysis of the conquests by rejecting “invalid titles of power”. He was the first to validate the papal bull of Alexander VI. , (known as "Donation Bull") doubted the rule of the newly discovered territories.

He did not accept the primacy of the emperor, nor the authority of the Pope (who lacks power in worldly matters), nor the right to voluntary submission or conversion of the Native Americans. They cannot be viewed as sinners or ill-informed: rather, they are inherently free and have legitimate claims to their land. When the Spaniards landed in America, they would not have had any legitimate title to occupy the country and make themselves their masters.

De Vitoria also examined the possibility of legal titles to rule over newly discovered lands. The first relates to the Ius peregrinandi et degendi ; this is the right of every person to travel to all countries in the world and to trade with residents there, regardless of who ruled the country or which religion it belongs to. If the indigenous peoples of America refused the ius peregrinandi et degendi , the party concerned had the right to defend itself and to remain in the land conquered in the course of this war of self-defense.

The second form of lawful title to rule over newly discovered lands relates to human rights . Limiting them can serve as the basis for a just war. Native Americans would have the right to oppose conversion, but they could not restrict the right of Spaniards to preach the gospel . However, due to the resulting deaths and destruction, it could be disproportionate to wage such a war.

Casuistically, Vitoria differentiates between further individual cases:

- When the pagan sovereign forces converted subjects to return to paganism.

- If there are a sufficiently large number of Christians in the newly discovered land who want the Pope to give rise to a Christian government.

- In the event of the overthrow of a tyrannical rule or government, harming the innocent (e.g. by demanding human sacrifice to the gods).

- When allies or friends are attacked. Vitoria cites the Tlaxcalteks as an example . They were allied with the Spaniards, but were subject to them and were attacked by the Aztecs . This could justify a just war and legitimize the conquests.

- Vitoria leaves open the legality of a further title of power, namely the case of a lack of just laws, magistrates, agricultural technologies etc. In any case, the custodial rule resulting from such a title must be exercised with Christian charity and for the benefit of the indigenous people.

The then ruler of Spain, Carlos V, rejected this doctrine of legitimate and illegitimate rulership titles. Because ultimately they meant that Spain had no special rights. He therefore tried unsuccessfully to prevent theologians from expressing their views on these matters.

Economy

The economic work of the School of Salamanca was initially largely forgotten, but is now considered a milestone in economics.

The economic theories of the Salamanca School received particular attention in Joseph Schumpeter's History of Economic Analysis (1954). Schumpeter, who studied scholastic doctrine in general, and Spanish scholasticism in particular, praised the high level of economics in sixteenth-century Spain. He argued that the Salamanca School most deserved the title of "Founder of Economics as Science". Although the School of Salamanca did not develop a complete economic doctrine, it did establish an economic theory for the first time in order to tackle the new social problems that arose at the end of the Middle Ages.

The English economic historian Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson has also published numerous articles and monographs on the economic teaching of the Salamanca School.

Although there seem to be no direct influences, the economic thinking of the Salamanca School is in many ways similar to today's Austrian School in economics . Murray Rothbard coined the term "Proto-Austrians" in this context. H. Predecessor of the Austrian School, for the followers of the School of Salamanca.

Economic theory of the Salamanca school: the prehistory

In 1517, de Vitoria, then teaching at the Sorbonne , was consulted by Spanish traders in Antwerp on the question of the moral legitimacy of trade with the aim of increasing personal wealth. From today's perspective, the question was about the moral foundations of entrepreneurship . De Vitoria and other theologians began to turn increasingly to economic issues. They distanced themselves from old views that they regarded as obsolete and instead introduced new ones based on natural law.

According to these views, the natural order is based on the "freedom of circulation" of people, goods and ideas. It allows people to get to know each other better and to strengthen the sense of community.

Private property

There was agreement among supporters of the Salamanca School that property has the positive effect of stimulating economic activity. This in turn contributes to general economic well-being. According to Diego de Covarrubias y Leiva (1512–1577), people not only have the right to private property, but also the right to benefit exclusively from the advantages of property. In times of great need, however, all private goods would become common goods.

Luis de Molina argued that owners of private property take better care of their goods than owners of common goods.

Money, value and price

Martín de Azpilcueta (1493–1586) and Luis de Molina developed an economic theory of value. In the case of valuable metals imported from America, de Azpilcueta demonstrated that in countries with low deposits of valuable metals the prices for these metals were higher than in countries in which they were more abundant. Valuable metals got their value in part from their scarcity. This scarcity theory of value was a forerunner of the quantitative theory of money which was later advocated by Jean Bodin (1530–1596).

Until then, the fair price was set using the medieval value theory of production costs. This is a variant of the modern operating cost theory that prevails today in labor theory . Diego de Covarrubias and Luis de Molina, on the other hand, developed a subjective theory of value: The usefulness of a good varies from person to person, so that a fair price automatically settles through mutual decisions of the market participants in free market trade. The prerequisite for this is that no distortions such as monopolies , fraud or state intervention disrupt the leveling off of the market price . In modern terms, the supporters of the Salamanca School advocated a free market theory in which the price of a good is determined by supply and demand .

According to Friedrich Hayek , the Salamanca School did not stick to this theory consistently.

Lending money and interest

Usury, what at that time was any charging of interest on a loan, has always been forbidden by the Roman Catholic Church. The Second Lateran Council condemned all forms of interest payments. The Vienne Council explicitly forbade usury and condemned any legislation that tolerated usury as heretical . The first scholastics reprimanded the charging of interest. In the medieval economic system, the need to take out a loan was solely a consequence of adverse circumstances, such as a bad harvest , storms or the outbreak of a fire. In these circumstances, interest demands were reprehensible.

During the Renaissance , the increased mobility in the population led to an increase in commercial activity. This provided entrepreneurs with the right opportunity to start new, lucrative businesses. Since borrowed money was no longer used exclusively for consumption but also for production , it could no longer be viewed in the same way as in the Middle Ages. The Salamanca School developed numerous reasons to justify charging interest. The person who received the loan benefited from it; Interest is the premium that compensates the lender of the money for the risk he has taken. Then there was the question of the opportunity costs : By granting the loan, the lender lost the opportunity to use the money differently. Ultimately, money itself was seen as a commodity, the use of money as something to be taken advantage of in the form of loans.

theology

During the Renaissance, theology was in decline due to rising humanism. The scholastic theology seemed limited to find solutions to current problems. Against this background, the Salamanca school turned more to “practical” theological questions of human life than the older scholasticism, which often discussed theoretical questions without “everyday relevance”. Under de Vitoria, the University of Salamanca ushered in a period of intensive research in theological field, particularly Thomism . His influence extended to European culture in general, especially European universities.

Moral philosophy

The School of Salamanca's contributions to law and economics were based on the new challenges and moral problems that society faced in the new conditions.

Your claim that morality does not depend on the divine was a downright revolutionary idea at the time. He decoupled the good from Christianity: Christians could also do badly and non-Christians good. This played an important role in connection with behavior towards pagans , because one could no longer assume that they were evil because they were not Christians.

While the Salamanca school was initially too casuistic , it later developed probabilism in search of general rules or principles . Mainly developed by Bartolomé de Medina and continued by Gabriel Vázquez and Francisco Suárez, probabilism became the most important school of moral philosophy in the following centuries.

The Mercy Dispute: The Controversy over the Polemic De auxiliis

The pamphlet De auxiliis was a dispute between Jesuits and Dominicans that occurred at the end of the 16th century. The subject of controversy was the doctrine of grace as well as the doctrine of predestination . Behind this is the question of how human freedom or free will is to be reconciled with Divine Omniscience . In 1582, the Jesuit Prudencio Montemayor and Frater Luis de León spoke publicly on the subject of free will . Domingo Báñez objected that they gave too much weight to free will and used terminology that sounded pagan. He therefore denounced them to the Spanish Inquisition under the pretext of Pelagianism . Montemayor and de León were revoked and banned from teaching and disseminating their views.

Subsequently, Báñez was denounced to the Holy See by de Leon. This accused him of following the teachings of Martin Luther . According to Lutheran teaching, man is corrupted as a consequence of original sin and cannot save himself. Only God can grant him grace. This view is also the essence of Pelagianism . Báñez was acquitted.

Nevertheless, this did not end the dispute that Luis de Molina continued with his work Concordia liberi arbitrii cum gratiae donis (1588). It is considered to be the best expression of the Jesuits' position on the question. The dispute continued over the years and included an attempt by the Dominicans to persuade Pope Clement VIII to condemn Molina's Concordia liberi arbitrii cum gratiae donis . Finally, in 1607, Pope Paul V recognized the freedom of both sides to defend their teachings and forbade either side to describe the other's position as heresy .

The problem of the existence of evil in the world

The existence of evil in a world created and ruled by an infinitely good and powerful God has long been considered a paradox. De Vitoria attempted a solution by arguing that free will is a gift from God to everyone. It is impossible that the will of every person always chooses the good. Therefore, evil arises as a necessary consequence of people's free will.

See also

literature

Primary literature

- Jeronimo Castillo de Bovadilla: Política para corregidores . Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local, Madrid 1978 (first edition: 1585, facsimile).

- Juan de Lugo: Disputationes de iustitia et iure . Sumptibus Petri Prost, Lyon 1642.

- Juan de Mariana : De monetae mutatione . 1605.

Secondary literature

- Wim Decock, Christiane Birr, Law and Morals in Scholasticism in the Early Modern Age (c. 1500-1750) , Berlin, De Gruyter, 2016.

- Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson : Economic Thought in Spain. Selected Essays of Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson . Edward Elgar Publishing, 1952, ISBN 978-1-85278-868-1 .

- Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson: The school of Salamanca: Readings in Spanish monetary theory, 1544-1605 . Clarendon Press, 1952.

- Raymund de Roover: Scholastic Economics. Survival and lasting influence from the Sixteenth Century to Adam Smith . In: Quarterly Journal of Economics . tape LXIX , May 1955, p. 161-190 , JSTOR : 1882146 .

- Michael Novak : The Catholic Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism . The Free Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-02-923235-4 .

- Jesús Huerta de Soto : La teoría bancaria en la Escuela de Salamanca . In: Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Complutense . tape 89 , 1998, ISSN 0210-1076 , pp. 141-165 ( libertaddigital.com ).

- Jesús Huerta de Soto : Biography of Juan de Mariana: The Influence of the Spanish Scholastics (1536-1624) . ( mises.org ).

- Merio Scattola : An Interdenominational Debate. How late Spanish scholasticism revised the political theology of the Middle Ages with the help of Aristotle. In: Alexander Fidora, u. a. (Ed.): Political Aristotelianism and Religion in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-05-004346-3 , p. 139–161 ( gbv.de [PDF]).

- Ernst Reibstein : Johannes Althusius as a continuation of the school of Salamanca. Studies on the history of ideas of the constitutional state and on the old Protestant doctrine of natural law. In: Freiburg legal and political science treatises. Volume 5, CF Müller, Karlsruhe 1955.

Individual evidence

Web links

- The Salamanca School A digital repository and dictionary of their legal and political language.