Self defense

As a self-defense is prevention and the defense of attacks on the physical or moral integrity of a person referred. The range of such attacks begins with disregard, careless statements, occupation of common room, continues through insults , bullying and bodily harm and extends to the most serious violent crimes. However, the perpetrator's goal is always to exercise power . The vast majority of such attacks are not carried out by strangers but by acquaintances (classmates, relatives, spouses). In defense against non-physical attacks, one speaks today of self-assertion (as a noun to assert oneself ).

Avoidance

There are a number of measures to avoid the attacks described, which can be learned in family education institutions and adult education centers , among other places . Here are just a few examples: If children do not get into the car with strangers and do not open the front door when the doorbell rings, then they avoid potentially dangerous situations. Likewise, those who steer clear of certain groups of people, avoid short cuts through deserted areas or do not allow themselves to be verbally provoked are also involved.

Another starting point is the fact that most perpetrators want to be successful, that is, they don't want to be “caught”. Perpetrators want to isolate their victim, i.e. cut them off from the protection of others. An effective self-defense is therefore making the crime public. Many methods of avoidance through deterrence are based on this . This includes not appearing helpless or over-anxious in public, but rather conveying through appearance that you can help yourself in case of doubt. When children go to school not alone but with friends; if they are not alone or in areas that are difficult to see in the playground, but in the vicinity of the supervisor, they deter possible attackers.

Defense

Defense against an attack becomes necessary when avoidance and deterrence have not worked, as well as in situations that cannot be dealt with by the police or lawyers.

A distinction must be made between two cases:

- The attacker is a stranger, it is a one-time, acute attack. Then the main goal is to get help and either end the situation or get out of it.

- The attacker is an acquaintance or relative, and the attack can continue over a longer period of time. Escape is often more difficult here, for example for children or the financially dependent.

Differentiation from self-defense

The legal terms self-defense and emergency aid only summarize measures that avert a current and unlawful attack on themselves or another, and self-defense also includes defense against immediate dangers from animals, as well as the protection of objects and other legal interests. Attacks that are not subject to criminal prosecution or whose prosecution by the authorities is not possible for practical reasons are not covered by the self-defense concept (example: bullying ).

The type and execution of the defense must be chosen so that the attack can be safely and definitively averted. If there are several options, the mildest should be chosen, but the defender does not have to take any risk if a less difficult remedy does not lead with certainty to success. Contrary to popular belief, the effects of self-defense on the attacker are irrelevant; It is not necessary to weigh the damage to health of the attacker, and injuries to the attacker resulting from self-defense are not punishable. The defense does not have to be expected to flee: "The right does not have to give way to the wrong."

Examples of self-defense situations

- Threat and coercion , including, for example, the threat of violence.

- Sexual coercion : Mostly affects women. A distinction is made between sexual harassment and sexual abuse .

- Burglary or trespassing

- Bullying : A distinction must be made here between physical bullying (pushing you into a corner, pushing around or forcing to the ground) and psychological bullying (insults, slander, spreading false facts)

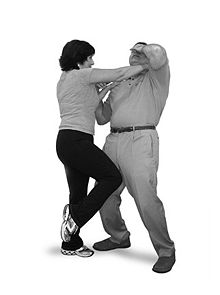

- Physical attack

Differentiation from martial arts and martial arts

Martial arts and self defense

Most martial arts were once soldier's craft, others have their origins in criminal structures ( savate ). Today they are sports with fixed rules. In realistic defense situations, however, there is a power imbalance from the outset: the attacker is stronger / more numerous than the defender. The basic spiritual orientation of martial arts, to defeat an equally strong partner , is in principle opposite to the self-defense situation, where you want to escape a superior attacker . Nevertheless, individual martial arts techniques can also be used in an emergency. In particular, full contact experiences of martial artists can prove to be helpful. The boundaries between martial arts and self-defense are difficult to see for laypeople, as almost all martial arts schools advertise self-defense and spiritual training. The decisive factor, however, is not which system you are training, but the specialist knowledge of the individual trainer, e.g. whether he knows how to recognize and avoid dangerous situations.

Martial arts as self defense

The term martial arts is to be distinguished from that of martial arts . Martial arts originated in times when people were often faced with fighting and had to defend themselves, with or without weapons. In order to master their complex and thus difficult to apply techniques and principles in an emergency, years of study of martial arts are often necessary. The best known include Wing Chun , Aikidō , Karate , Taekwondo and Jiu Jitsu, as well as the judo self-defense derived from them. Taekwondo has now become an Olympic discipline, and karate a sport recognized by the IOC .

If a martial art is to be carried out according to a sporting standard, regulations must be made and certain techniques must be excluded from the outset in order to prevent immediate damage to the opponent, e.g. B. the low blow in boxing or punches in the face in Olympic Taekwondo. "If something [...] is considered a violation in martial arts, it is probably ideal for self-defense." (John Wiseman, trainer of the British special unit SAS ). As a logical consequence these martial arts, taught from a modern point of view, have developed into martial arts. One can also argue from this that traditional disciplines optimized for self-defense hardly strive for a disciplinary limitation of their technical repertoire.

Self-defense systems

Special self-defense systems were created with the sole focus on self-defense. They lack the artistic and spiritual demands of a martial art. These systems often have a military background (hand-to-hand combat ) and are designed to teach students basic self-defense skills as quickly as possible. Examples of popular systems are Krav Maga and Combatives .

Assertion

Self-assertion can only be vaguely differentiated from self-defense: this term is usually used to describe the enforcement of one's own rights with verbal, inviolable means. Certain strategic techniques that serve to deal with threatening conflicts in a differentiated manner combine self-defense with self-assertion e.g. B. the Wendo developed for women . Especially people with low self-esteem and low social knowledge find it difficult to assert their needs, views and interests against others, even in a group. Therefore, they are more often victims of the psychological manipulative "power games" of everyday life, which in the worst case can even lead to bullying . Self-defense is concerned with self-defense against these attacks, which are much more common than acute physical violence. “Self-assertion training is a collection of methods designed to reduce social fears and contact disorders such as self-insecurity. Assertiveness and social skills should be learned. "

The problem is that bullying is usually difficult to prove, as it usually occurs through a variety of different activities over a long period of time, more psychologically than physically. The "self-assertion by hitting", however, can be proven quickly, especially if the attacker acts against a group whose members can later appear as witnesses.

Self-defense in international law

The right of self-defense is also anchored in international law . Article 51 of the UN Charter speaks of a “natural right to individual or collective self-defense”. Individual self-defense is understood here as the right of a single state to defend itself against armed conflicts. In the case of collective defense, the aim is to provide assistance from a state that is not threatened to another state that is exposed to an armed attack. The appeal to this right of self-defense must be an act against a concrete, imminent danger ( preemption ). Whether a threat, a breach of peace or an act of aggression is present is determined by the United Nations Security Council in accordance with Article 39 of the UN Charter . Defense alliances have been formed within the limits of Article 51 of the UN Charter; one of them is NATO . Prevention, on the other hand, is aimed at a merely indirect threat and is impermissible under international law. The preventive doctrine of the USA - for example because of the "war on terror" or against supposed nuclear weapons-producing states - is understood in the USA as a permissible preemption, but is contrary to international law because so far neither plans nor preparatory actions have been proven to be an imminent threat. However, in its resolutions 1368 (2001) and 1373 (2001), the Security Council reaffirmed the right to self-defense within the meaning of the UN Charter, citing the acts of terrorism.

See also

Military use of unarmed self-defense techniques

literature

- Barbara Berckhan: The more intelligent way of defending yourself against stupid sayings - self-defense with words . Kösel, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-466-30446-6

- Sunny Graff: Not with me! . Orlanda Frauenverlag, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-936937-19-2 .

- Anita Heiliger: perpetrator strategies and prevention . Women's offensive, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-88104-319-5 .

- Ulrike Herle: Self-defense begins in the head . Piper, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-492-11721-X .

- Fritz Hücker: Rhetorical de-escalation . Boorberg, 4th edition, Stuttgart / Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-415-05822-4 .

- Joachim Kersten : Good and bad . de Gruyter, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-11-015445-5 .

- Keith R. Kernspecht, André Karkalis: Defend yourself, self-defense for women . Heel, 2003, ISBN 3-89365-964-1 .

- Michael Korn: Self-Defense for Children . Pietsch, 2006, ISBN 3-613-50519-3 .

- Friedrich Lösel , Thomas Bliesener: Aggression and delinquency among young people . Luchterhand, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-472-05368-2 .

- Eva Marsal: Inviolable self-assertion . Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1997, ISBN 3-8100-1214-9 .

- Dan Olweus: Violence in School . Hans Huber, Bern 1996, ISBN 3-456-82786-5 .

- Peyton Quinn: A Bouncer's Guide to Barroom Brawling . Palladin Press, Boulder (USA) 1990, ISBN 0-87364-586-3 .

- Sanford Strong: Strong on Defense. Survival Rules to Protect You and Your Family from Crime . Pocket Books, New York 1996, ISBN 0-671-53511-0 .

- John Wiseman: City Survival . Pietsch, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-613-50336-0 .

- Horst Wolf : Judo self-defense (contains a contribution on the legal status of self-defense by Wilfried Friebel ; Illustration: Otto Hartmann), Sportverlag Berlin (1986), ISBN 3-328-00141-7 .

Web links

- Information website of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Austria) on crime prevention

- Ways out of violence, a guide to the police ( Memento from May 14, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Khaleghl Quinn (1994): Hands off! Two thousand and one. ISBN 3-86150-092-2 .

- ↑ Denise Caignon, Gail Groves: Quick-witted Women. Successful against everyday violence . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1998, ISBN 3-596-13876-0 .

- ↑ Hanni Härtel: The way of the tigress . Econ, Düsseldorf 1996. ISBN 3-612-20531-5 .

- ↑ Barbara Berckhan: Gentle self-assertion . Kösel, Munich 2006. ISBN 3-466-30707-4 .

- ↑ When can you defend yourself? Retrieved October 28, 2017 .

- ^ Peyton Quinn: Real Fighting . Palladin Press, Boulder (USA), 1996. ISBN 0-87364-893-5 .

- ↑ Horst Wolf: Judo self-defense. Sportverlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-328-00141-7

- ↑ Bernd Linn: Judo-related self-defense. Meyer & Meyer Verlag, Aachen 2015, ISBN 978-3-89899-881-9

- ^ John Wiseman: City Survival . Pietsch, Stuttgart 1999. ISBN 3-613-50336-0 , p. 27.

- ↑ Eva Marsal: Inherent Self-Assertion , Leske + Budrich, 1997, ISBN 3-8100-1214-9 .

- ^ PL Janssen, W. Gehlen: Neurology and Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy . Thieme, Stuttgart 1994. ISBN 3-13-543104-5 .

- ↑ Stephan Hobe / Otto Kimminich, Introduction to Völkerrecht , 2004, p. 336 ; Armin Kockel, The mutual assistance clause in the Lisbon Treaty , 2012.