mobbing

Bullying or bullying as a sociological term describes the repeated and regular, predominantly emotional bullying, tormenting and hurting an individual by any type of group or individual. Bullying can e.g. B. take place in the family, in a peer group , in school, at work, in clubs , in residential facilities (homes) or prisons, in residential areas (neighborhoods) or on the Internet ( cyber bullying ). Typical acts of bullying include humiliation , spreading false assertions, assigning useless tasks, threats of violence , social exclusion, or continued inappropriate criticism of an individual or their actions.

etymology

The term bullying was adopted from English in the second half of the 20th century. The verb to mob , from which the word mobbing is derived, initially means in general "to harass, to mob." The German word Mob , which is also borrowed from English, denotes an agitated crowd as well as generally "Meute, rabble, rabble, gang" .

In contrast to the Scandinavian countries and the German-speaking countries, the term bullying is usually used in English-speaking countries to refer to bullying. In German translation, bully means “brutal guy, thug, tyrant , mouth hero” as a noun and “tyrannize, bully, intimidate, pester” as a verb.

Concept history

In 1963, the behavioral scientist Konrad Lorenz coined the term hating : Lorenz used it to describe group attacks by animals on a predator or other superior enemy - there by geese on a fox. In 1969 the Swedish doctor Peter-Paul Heinemann used the term mobb (n) ing for the phenomenon that groups attack a person who behaves differently from the norm .

The term became known in its current meaning through the Swedish doctor and psychologist Heinz Leymann , who emigrated from Germany and spoke of bullying in relation to working life. His research into direct and indirect attacks in the workplace began in the late 1970s. At the beginning of the nineties Leymann published his first paper, which summarized the previous scientific knowledge. The reports initially only aroused interest in the northern European countries and were received with a delay in central Europe. Publications, haunting case reports, public discussions, the inclusion of the topic by management consultants, trade unions, employers and other associations as well as in medicine made the topic of bullying increasingly known to a wider public.

definition

In colloquial terms, bullying means that someone - mostly at school or at work - is continuously annoyed, harassed, embarrassed, mostly avoided in passive form as a refusal to contact or treated in some other way asocial and his dignity violated. There is no generally accepted definition. According to Christoph Seydl, most researchers emphasize the following points:

- Behavioral Patterns: Bullying relates to a behavioral pattern and not to a single act. The actions are systematic, that is, they are repeated over and over again.

- Negative actions: Bullying behavior can be verbal (e.g. verbal abuse), non-verbal (e.g. withholding information) or physical (e.g. beating up). Such acts are commonly viewed as hostile, aggressive , destructive, and unethical .

- Unequal power relations : The participants have different ways of influencing the respective situation. One person is inferior or superior to another person. No difference in rank is necessary for this. Inequality can be due to the sheer number: many people against one person.

- Victim: In the course of the action, a victim develops who has difficulties defending itself due to unequal power relations.

Dan Olweus , on the other hand, also regards individual harassing incidents as bullying if they are very serious.

Manifestations

At work

Actions

In a qualitative interview study (n = 300), Heinz Leymann identified 45 acts of bullying that he considered relevant. Martin Wolmerath and Axel Esser identified over 100 different acts of bullying without claiming to be exhaustive. Typical acts of bullying relate to organizational measures ( e.g. deprivation of competencies or the assignment of meaningless work tasks; also known as training ), social isolation ( e.g. avoidance and exclusion of the person), attacks on the person and their privacy (e.g. ridiculing the person), verbal violence ( e.g. oral threat or humiliation), threat or exercise of physical violence and rumors.

Measurement

In empirical studies, it is necessary to make mobbing measurable ( operationalization ). These operationalizations are mostly derived from the definitions used. Well-known instruments are the Negative Acts Questionnaire and the Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror . There are also lesser-known measuring instruments, such as the burnout bullying inventory constructed according to psychometric principles.

Course forms and distribution

In the workplace, a distinction is made between bullying on the part of supervisors and that which comes from employees of the same or lower ranking. In the literature, the former is sometimes referred to as " bossing " (English downward bullying ) or power harassment and the latter as " staffing " (English upward bullying ). Psychological terror, which is carried out by people who are higher in the company hierarchy, occurs in 40 percent of the cases in Germany, and in another ten percent the boss and employee are bullying together. Some experts even assume a bossing rate of 70 percent. On the other hand, only in two percent of all cases a superior is bullied by his subordinates. Moreover horizontal bullying (English horizontal bullying ); that is, the person concerned is bullied by colleagues who are hierarchically equal. More than 20 percent of all victims of bullying describe a colleague as a perpetrator. Roughly the same number of people affected indicate that the bullying came from a group of colleagues. A little less than 15 percent of all victims of bullying in Germany are convinced that they are being bullied by both their superiors and colleagues. With regard to authors, IG Metall has determined the following frequency distribution:

- 44%: colleagues

- 37%: superiors

- 10%: Colleagues and superiors together

- 9%: subordinates

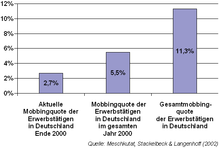

The estimates for the current number of people affected by bullying in Germany amount to over 1,000,000 employees (2.7%). In Switzerland there are almost 100,000 people in employment who declare themselves to be victims of bullying (4.4%). There are no representative figures for Austria . In a survey of randomly selected large and medium-sized companies with works councils (30 companies and 249 employees ) in Upper Austria, 5.3% of those questioned felt that they were currently affected by bullying. Extrapolated to Austria, that would mean over 200,000 employed people. The number of people affected within a year or in relation to the entire working life is significantly higher than the actual bullying rate.

In their Gießen sample, Knorz and Zapf showed that in the majority of all cases both sexes are represented in the perpetrators. Other studies show that the perpetrators are mainly men, while the majority of the victims are women. This may be due to the higher employment rate of the male population and in particular the superior status that men have more often. In addition, women are generally more willing to talk about bullying, admit psychological and health problems and take advantage of offers of help. Men tend to view bullying as an individual failure to be concealed.

causes

Bullying research tries to find out the causes of this phenomenon. It is generally assumed that situational factors on the one hand and personality traits of the victim and the perpetrator on the other are responsible for the occurrence of bullying. Researchers who view bullying as a complex psychosocial process place significant importance on the work environment, the organization, all those involved and the nature of interpersonal interaction in organizations.

According to some bullying researchers, victims of bullying are, on average, more fearful, submissive and conflict-averse. Since the studies on this are exclusively cross-sectional studies , the findings are highly controversial. Without longitudinal studies, it cannot be ruled out that these differences in the personality of victims are not the cause but the consequence of the respective bullying incident. In addition, the victims of bullying are inferior to the bullying, so that the behaviors observed can also be situational.

Another cause of bullying is the bully's personality. Some authors assume that people turn into bullies to compensate for their low self-confidence . Bullies use the victims as whipping boys and as a projection surface for their own negative emotions. Studies by Olweus (including studies of stress hormones and projective tests ) do not support this assumption. His research suggests the opposite; that is, the perpetrators are, on average, more confident and less anxious. Leymann relies on his own research results, according to which in principle any person can become a perpetrator if the situation-related conditions are right.

Most common among researchers is the belief that structural factors trigger bullying. Bullying is a weapon ( social sanction ) in the internal competition for scarce resources (promotion positions, job security). With growing economic boom , the internal bullying therefore decreases in the recession - especially if unemployment is threatening - to.

Extremely poor work organization and production methods such as unclear responsibilities, monotony, stress, general deficiencies in the communication and information structure, unfair distribution of work, excessive and insufficient demands, contradicting instructions, lack of scope for action or the need to cooperate are all causes of bullying. There are also favorable factors, such as “preaching water and drinking wine” on the part of management, competition among employees or an organizational culture that has no inhibiting mechanisms against bullying. Profound organizational changes are also considered to be triggers for bullying. The risk of being bullied is significantly higher in organizations in which technological change or a change in ownership structure takes place.

Unions and researchers report that some companies use bullying as a strategy to persuade (certain) employees to resign, thereby circumventing dismissal protection regulations or avoiding severance payments .

On the theoretical level, different social phenomena are cited which are used as the cause of bullying. Some experts cite stigma and scapegoat phenomena as causes. Heinemann describes bullying as an ingroup / outgroup phenomenon where an individual is excluded from a social group . Other researchers cite conflicts as the cause. Oswald Neuberger's view that bullying is an escalated conflict is controversial in research. Empirical findings show a connection between bullying and role conflict .

consequences

Mobbing has far-reaching negative consequences for the health as well as for the professional and private situation of the victim, whereby Neuberger in particular points out that the perpetrator-victim distinction is very problematic.

Regular hostile attacks evoke negative feelings and strong insecurities in those affected, which as a rule has consequences for their work and performance behavior. 98.7% of German bullying victims report negative effects in this regard. According to the bullying report , victims most frequently name demotivation (71.9%), strong distrust (67.9%), nervousness (60.9%), social withdrawal (58.9%), feelings of powerlessness (57.7%), Internal resignation (57.3%), performance and thinking blocks (57.0%), self-doubt about one's own abilities (54.3%), anxiety (53.2%) and poor concentration (51.5%). Professionally, bullying can lead to dismissal, transfer and disability of the victim.

The private and family effects of bullying on those affected are complex. According to the bullying report, the most frequent consequences include imbalance (23.7%), social isolation (21.6%), quarrels in the family or partnership (19.7%), general stress (16.6%), and financial problems (15.4%), listlessness (13.9%), aggressiveness (9.6%), overshadowing of private life (9.6%) and depression (9.3%).

The consequences of bullying can go well beyond a mere loss of quality of life for the person concerned. According to the bullying report, 43.9% of those affected fall ill, of which almost half have been sick for more than six weeks. Aggressive bullying can lead to the victim's “bullying syndrome”, which is brought close to or even equated with post-traumatic stress disorder . The "bullying syndrome" is seen as a manifestation of a "cumulative traumatic stress disorder" (KTBS), the inclusion of which as subchapter F43.3 in the German version of the 10th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) is already available for Applied for in 2014, but has not yet been implemented.

In connection with the cases of illness, high economic and economic conflict costs can be assumed: According to estimates, this financial damage extends well into the double-digit billion range. They are caused by medical treatment and rehabilitation cures or even permanent unemployment, incapacity for work and early retirement of those affected.

Significant financial burdens arise for the individual company (or institution). This includes underperformance, fluctuation and absenteeism of the employee affected by bullying. The German Trade Union Federation (DGB) puts the operational costs of a day off due to bullying at 103 to 410 euros. In addition, there are the significantly higher "indirect" costs: direct and indirect error costs , costs due to direct loss of performance of the employees involved, costs due to disruptions in the social working community, loss of motivation, creativity and image ( reputation ). There are currently no reliable calculations of the average costs of bullying cases.

Prevention and intervention

There are several ways you can do something about bullying. In many cases (according to the bullying report 22.5%) victims of bullying see their own resignation as the only way out. Measures can be taken by the victims as well as the company.

Practitioners recommend those affected to set boundaries for the perpetrator, as far as they can and they are in the necessary mental state. It is therefore extremely important that the victim signals a clear “stop!” To the bully as soon as possible. Otherwise the perpetrator may feel confirmed that he can continue to bully calmly. According to Esser / Wolmerath, this action has a twofold effect. On the one hand, it represents an inner reversal in the affected person, no longer feeling like a defenseless victim. On the other hand, the action signals the end of the "easy game" to the bullies. It should be clear to the person concerned that the first sign of resistance can probably lead to a change in the situation in which an escalation is likely. It is advisable to seek the support of a bullying advisor.

Affected people who are unable to confront the perpetrator themselves can seek help within the company. The first point of contact is always the line manager, or if he is involved in the bullying, his line manager. Colleagues can also be used as support. Conversations with a perpetrator should always be conducted in groups of three. The third person serves as a witness, catalyst , moderator , coach or mediator . As a representative of the employee's interests, the works council or the staff council can be suitable as a partner for victims of bullying, especially if managers are involved in the bullying. However, especially in smaller companies and in the public sector (staff council), the works council may show solidarity with the attackers. External advice centers are another point of contact for victims of bullying.

A "bullying diary" is a useful tool for victims, in which the victim should record the course of the bullying situation as precisely as possible. In doing so, the person concerned records the time and the respective situation in which the assault occurred, who committed which act, who was present and who may have noticed the situation, and how he felt. Any physical or health reactions as a result and the time interval in which they occurred are noted.

In addition, this diary offers the opportunity to document any doctor visits that are necessary due to the incidents. In the event of a court hearing, the bullying diary serves as an aid to preserving evidence .

Company strategies against bullying can be divided into prevention and intervention .

A central preventive measure is the development of an organizational and management culture that guarantees constructive cooperation in which each individual is valued by everyone. Secondary measures are: education (brochures, posters, discussions, ...), installation of an in-house infrastructure against bullying at the workplace (e.g. company agreement for fairness in the workplace), the systematic collection of data on bullying in the company or the elimination of company role conflicts .

The first step in the intervention is to stop the bully, e.g. B. through mediation . However, mediation only offers a chance of success if the perpetrator wants a solution to the conflict. After the bully has been stopped, support for the victim becomes very important. The perpetrator must also be supported in such a way that he changes his behavior not only in the current case, but fundamentally. Psychotherapy, self-help groups and medical therapies are considered appropriate support measures for the victim and the perpetrator.

The employer is responsible for shaping the corporate and management culture, for occupational safety and for intervention in specific cases of bullying. If it can be proven that he does not perform this task, he can be prosecuted by the victim under labor and civil law .

Legal situation

The legislation regarding bullying at work in different countries is very different. In some countries (such as Sweden, France or Spain) there are statutory provisions to protect against bullying in the workplace. In other countries there is little or no protection against bullying as long as individual acts do not demonstrably meet legal requirements.

At school

Bullying in school (also called “bullying”) means “togetherness” directed against students, annoying, attacking, harassing and securing. Above all, the perpetrators should give preference to weaker and more fearful victims. The psychologist and bullying researcher Olweus differentiates between two ideal types of bullying victims in schools, the passive victim and the provocative victim. According to school researcher Wolfgang Melzer, bullying at school cannot be traced back to specific perpetrators and victims, but to the school climate.

On the Internet

Cyber-bullying is defined as various forms of defamation, harassment, harassment and coercion of other people or companies with the help of electronic means of communication via the Internet, in chat rooms, instant messaging and / or via mobile phones. This also includes the theft of (virtual) identities in order to insult or conduct business in someone else's name. Victims are bullied through exposure on the Internet, constant harassment or spreading false claims.

In the home

Mobbing in the home is a phenomenon that was described by the social epidemiologist Markus Dietl in his book of the same name. He notes that both clients and employees are exposed to acts of bullying and describes empathic concepts as a solution.

The sociologist Erving Goffman studied violent incidents in homes as early as the 1970s. He introduced the term total institution, which includes not only homes but also other facilities such as prisons and psychiatric hospitals.

literature

Scientific literature on workplace bullying

- Heinz Leymann : Mobbing - psychological terror in the workplace and how you can defend yourself against it . Rowohlt, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-499-13351-2 .

- Oswald Neuberger : Mobbing - playing badly in organizations . Hampp, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-87988-093-X .

- Klaus Niedl: Mobbing / Bullying at the Workplace - An empirical analysis of the phenomenon as well as the effects of systematic hostilities relevant to personnel management . Hampp, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-87988-114-6 .

- Martin Wolmerath: Mobbing. Legal Handbook for Practice , 4th edition, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2013, ISBN 978-3-8329-7763-4

Introductions to workplace bullying

- Josef Schwickerath (Ed.): Mobbing in the workplace - basics, counseling and treatment concepts. Pabst, Lengerich 2004, ISBN 3-89967-112-0 .

- Ståle Einarsen, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf , Cary Cooper: Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace - Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd Edition. CRC Press, Boca Raton 2010, ISBN 978-1-4398-0489-6 .

- Anka Kampka, Nathalie Brede, Ansgar Brede: Don't be afraid of bullying. Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-86012-2 .

- Bernd Jaenicke : Mobbing in the company. Updated new edition in: Das Personalbüro. Haufe Verlag, Freiburg, September 2007.

Representative studies of workplace bullying

- Bärbel Meschkutat, Martina Stackelbeck, Georg Langenhoff: The Mobbing Report - Representative Study for the Federal Republic of Germany (

614 kB). Wirtschaftsverlag NW, Dortmund 2002, ISBN 3-89701-822-5 .

614 kB). Wirtschaftsverlag NW, Dortmund 2002, ISBN 3-89701-822-5 . - Alain Kiener, Maggie Graf, Jürg Schiffer, Ernesta von Holzen Beusch, Maya Fahrni: Mobbing and other psychosocial tensions at work in Switzerland ( Memento from August 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (

669 kB). State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), Bern 2002.

669 kB). State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), Bern 2002.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ursula Kraif (Red.): Duden. The foreign dictionary. 9th edition. Dudenverlag, Mannheim 2007, ISBN 978-3-411-04059-9 ( The Duden in twelve volumes, vol. 5), p. 667.

- ↑ a b Björn Eriksson: Mobbning. En sociologiskussion. In: Sociologisk Forskning. Vol. 2001, No. 2, ISSN 0038-0342 , pp. 8-43.

- ↑ a b Heinz Leymann: Manual for the LIPT questionnaire. Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror. Dgtv, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-87159-333-8 . (German Society for Behavioral Therapy, materials, vol. 33), accompanying material questionnaire, p. 2.

- ↑ Duden: The dictionary of origin. Lemmata bullying and mob .

- ↑ Ola Agevall: The Production of Meaning in relation bullying. Article presented at The Society for the Study of Social Problems 54th Annual Meeting. San Francisco 2004, 13-15 August 2004.

- ↑ Langenscheidt's concise dictionary of English. Berlin u. a. O. 1988, Lemma bully .

- ^ A b Peter-Paul Heinemann: Mobbning - gruppvåld bland barn och vuxna. Natur och Kultur, Stockholm 1972, ISBN 91-27-17640-1 .

- ↑ Dan Olweus: Hackkycklingar och översittare - forskning om skolmobbning. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm 1973, ISBN 91-20-03674-4 .

- ↑ a b c Christoph Seydl: Mobbing in the tense relationship between social norms - a dissonance theoretical consideration with investigation. Trauner, Linz 2007, ISBN 978-3-85499-312-4 .

- ↑ a b c d Dan Olweus: Mobbning - vad vi vet och vad vi kan göra. Liber, Stockholm 1986, ISBN 91-40-71638-4 .

- ↑ a b Martin Wolmerath, Axel Esser. Mobbing - Approaches for Works Council Work (PDF; 117 kB) . In: Labor law in the company. Vol. 2000, No. 7, 2000, ISSN 0174-1225 , pp. 388-391.

- ↑ Dieter Zapf. Bullying - an extreme form of social stress in organizations. In: Psychology of Work Safety. Vol. 10, 2000, ISBN 3-89334-356-3 , pp. 142-149.

- ↑ Satow, L. (2013). Burnout bullying inventory (BMI) [PSYNDEX test no. 9006565]. In Leibniz Center for Psychological Information and Documentation (ZPID) (Ed.), Electronic Test Archive . Trier: ZPID. PDF

- ↑ What is bullying? ( Memento from June 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the Austrian Federation of Trade Unions

- ↑ ZEIT online: Psychological terror as a management style

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Bärbel Meschkutat, Martina Stackelbeck, Georg Langenhoff: The Mobbing Report - Representative Study for the Federal Republic of Germany (PDF; 614 kB) . Wirtschaftsverlag NW, Dortmund 2002, ISBN 3-89701-822-5 .

- ↑ FOCUS online: research into causes

- ↑ Alain Kiener, Maggie Graf, Jürg Schiffer, Ernesta von Holzen Beusch, Maya Fahrni: Mobbing and other psychosocial tensions at work in Switzerland (PDF; 669 kB) ( Memento from August 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), Bern 2002

- ↑ Carmen Knorz, Dieter Zapf : Mobbing - an extreme form of social stressors in the workplace. In: Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 40, 1996, ISSN 0932-4089 , pp. 12-21.

- ↑ Ståle Einarsen, Anders Skogstad: Bullying at Work. Epidemiological Findings in Public and Private Organizations. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 5, No. 2, 1996, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 185-201.

- ↑ Dieter Zapf: Mobbing in Organizations - Overview of the State of Research (PDF; 2.55 MB) ( Memento from July 16, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). In: Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 43, 1999, ISSN 0932-4089 , pp. 1-25.

- ↑ Maarit Vartia: Workplace Bullying - A Study on the Work Environment, Well-Being and Health. (PDF; 618 kB) Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki 2003, ISBN 951-802-518-5 .

- ↑ Thomas Rammsayer, Kathrin Schmiga: Mobbing and personality - differences in basic personality dimensions between those affected by bullying and those not affected. In: Business Psychology. Vol. 2/2003, 2003, ISSN 1615-7729 , pp. 3-11.

- ^ Iain Coyne, Elizabeth Seigne, Peter Randall: Predicting Workplace Victim Status from Personality. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 9, 2000, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 335-349.

- ↑ a b c d Heinz Leymann: The Content and Development of Mobbing at Work. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 5, 1996, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 165-184.

- ^ Marie-France Hirigoyen: Le harcèlement moral: la violence perverse au quotidien. Syros, Paris 1998, ISBN 978-2-84146-599-6 .

- ↑ Oswald Neuberger. Bullying - playing badly in organizations. Hampp, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-87988-146-4 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Leymann: Vuxenmobbning - om psykiskt våld i arbetslivet. Student literature, Lund 1986, ISBN 91-44-24281-6 .

- ↑ Ståle Einarsen, Anders Skogstad: Bullying at Work - Epidemiological Findings in Public and Private Organizations. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 5, 1996, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 185-201.

- ↑ Maarit Vartia: The Source of Bullying - Psychological Work Environment and Organizational Climate. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 5, 1996, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 203-214.

- ^ A b Dieter Zapf, Carmen Knorz, Matthias Kulla: On the Relationship between Mobbing Factors and Job Content, Social Work Environment and Heal Outcomes. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 5, 1996, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 215-237.

- ↑ Anita Schéele: Mobbning - en arbetsmiljöfråga. Arbetarskyddsnämnden, Stockholm 1993, ISBN 91-7522-386-4 .

- ^ Anna Luzio-Lockett: Enhancing Relationships within Organizations - an Examination of a Proactive Approach to "Bullying at Work". In: Employee Counseling Today. Vol. 7, 1995, ISSN 0955-8217 , pp. 12-22.

- ↑ Andreas Patrick Daniel Liefooghe: Employee Accounts of Bullying at Work. In: International Journal of Management and Decision Making. Vol. 4, 2003, ISSN 1462-4621 , pp. 24-34.

- ^ Adrienne B. Hubert, Marc van Veldhoven: Risk Sectors for Undesirable Behavior and Mobbing. In: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 10, 2001, ISSN 1359-432X , pp. 415-424.

- ^ A b Carroll M. Brodsky: The Harassed Worker. Lexington Books, Lexington 1976, ISBN 0-669-01041-3 .

- ↑ Peter Randall: Adult bullying - Perpetrators and Victims. Routledge, London 1997, ISBN 0-415-12672-X .

- ^ Vittorio Di Martino, Helge Hoel, Cary L. Cooper: Preventing Violence and Harassment in the Workplace (PDF file; 388 kB) . Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg 2003, ISBN 92-897-0211-7 .

- ^ Christopher B. Meek, The Dark Side of Japanese Management in the 1990s - Karoshi and Ijime in the Japanese Workplace. In: Journal of Managerial Psychology. Vol. 19, 2004, ISSN 0268-3946 , pp. 312-331.

- ↑ Ingela Thylefors: Syndabockar - om mobbning och kränkande särbehandling i arbetslivet. Natur och Kultur, Stockholm 1999, ISBN 91-27-07559-1 .

- ^ Oswald Neuberger: Mobbing - playing badly in organizations. Hampp, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-87988-146-4 .

- ↑ Ståle Einarsen, Bjørn Inge Raknes, Stig Berge Matthiesen: Bullying and Harassment at Work and Their Relationships to Work Environment Quality - an Exploratory Study. In: European Work and Organizational Psychologist. Vol. 4, ISSN 0960-2003 , pp. 381-401.

- ↑ Argeo Bämayr: Das Mobbingsyndrom: Diagnosis, therapy and assessment in the context of the ubiquitous psychological violence practiced in Germany. Munich University Press Series, Vol. 4. Bochumer Universitätsverlag · Westdeutscher Universitätsverlag, Bochum 2012, ISBN 978-3-89966-514-7

- ^ H. Javidi, M. Yadollahie: Post-traumatic stress disorder. In: The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Vol. 3, 2012, pp. 2-9 ( HTML version , PDF version ).

- ^ Alfredo Rodríguez-Muñoz, Bernardo Moreno-Jiménez, Ana Isabel Sanz Vergel, Eva Garrosa Hernández: Post-Traumatic Symptoms Among Victims of Workplace Bullying: Exploring Gender Differences and Shattered Assumptions. In: Journal of Applied Social Psychology. Vol. 40, No. 10, 2010, pp. 2616–2635, doi : 10.1111 / j.1559-1816.2010.00673.x (alternative full text access : ResearchGate ).

- ↑ Claire Bonafons, Louis Jehel, Alain Coroller-Béquet: Specificity of the links between workplace harassment and PTSD: primary results using court decisions, a pilot study in France. In: International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Vol. 82, No. 5, 2009, pp. 663-668, doi : 10.1007 / s00420-008-0370-9

- ↑ Argeo Bämayr: Proposal for amendment to the ICD-10-GM 2014. ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information DIMDI

- ↑ "Costs for the national economy as a whole: the experts estimate 40 to 100 billion marks." Claudia Weingartner: Those who do not defend themselves live wrong. ( Memento from July 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Focus online

- ↑ The cost of bullying. ( Memento of February 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Web presence of the German Federation of Trade Unions

- ↑ How to deal with bullying and sexual harassment in the workplace ( memento from March 12, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) information sheet from the personnel office of the Canton of Lucerne, p. 3

- ^ A b Axel Esser, Martin Wolmerath: Mobbing - the counselor for those affected and their lobbying . Bund-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-7663-3214-7 .

- ↑ a b Federal Ministry for Social Security, Generations and Consumer Protection (Ed.): Fair Play. Agreement for a dignified collaboration. Federal Ministry for Social Security, Generations and Consumer Protection , Vienna 2007, ISBN 3-85010-168-1 .

- ↑ EU strategy paper COM (2002) 118 final.

- ↑ a b c working paper of the European Parliament SOCI 108 EN

- ↑ Peter K. Smith, Helen Cowie, Ragnar F. Olafsson, Andy PD Liefooghe: Definitions of Bullying - A Comparison of Terms Used, and Age and Gender Differences, in a Fourteen-Country International Comparison. In: Child Development. Vol. 73, No. 4, 2002, ISSN 0009-3920 , pp. 1119-1133.

- ↑ Norbert Kühne: Mob, humiliate and harass. Bullying in kindergarten. In: small & large - magazine for early childhood education. Vol. 2007, No. 12, 2007, ISSN 0863-4386 , pp. 45-46.

- ^ Ulrich Winterfeld: Violence in society - a topic for psychologists. In: Report Psychology. Vol. 32, No. 11-12, 2007, ISSN 0344-9602 , p. 481.

- ↑ Markus Dietl: Mobbing in the home: Nonviolent solutions. Springer, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-06250-7 .

- ↑ Erving Goffman: On the social situation of psychiatric patients and other inmates. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 978-3-518-10678-5 .